Abstract

Purpose

The purpose of this study was to determine the feasibility and functionality of MyDiaText™, a website and text messaging platform created to support behavior change in adolescents with type 1 diabetes (T1DM) and to evaluate user satisfaction of the application.

Methods

This study was a nonrandomized, prospective, pilot trial to test the feasibility and user interface with MyDiaText, a text message system for 10- to 17-year-old youths with newly diagnosed T1DM. Feasibility was evaluated by assessing for the user’s ability to create a profile on the website. Functionality was defined by assessing whether a subject responded to at least 2 text messages per week and by their accumulating points on the website. User satisfaction of the text messaging system was assessed using an electronic survey. The 4 phases of this study were community engagement—advisory sessions, screening and enrollment, intervention, and follow-up.

Results

Twenty subjects (14 male, 6 female) were enrolled. All subjects were able to create a profile, and of these, 86% responded to at least 2 text messages per week. A survey administered during follow-up showed that users enjoyed reading text messages, found them useful, and thought the frequency of messages was appropriate.

Conclusion

MyDiaText is a feasible, functional behavioral support tool for youth with T1DM. Users of the application reported high satisfaction with text messages and the reward system.

Introduction

Type 1 diabetes (T1DM) is an autoimmune disease that causes insulin deficiency, affecting at least 192,000 children in the United States, with 18,000 diagnosed with T1DM each year.1 In pediatric patients with T1DM, maintaining hemoglobin A1C (A1C) levels below 7.5% is recommended to prevent short- and long-term complications.2 Optimal disease control may prevent or decrease the risk of complications. Adolescence is known to be a time of suboptimal diabetes control.3 Adolescent patients often have difficulty adhering to a diabetes management program that includes healthy eating, regular testing of blood glucose, and titrating insulin through understanding the relationship between insulin and blood glucose levels. The causes of poor control in adolescence are multifactorial, including but not limited to mental health vulnerabilities, changing cognitive and family dynamics, and shifting peer relationships.4 With 88% of teens owning a smartphone or basic cell phone,5 interventions are being developed using mobile technology to increase adherence to diabetes treatment plans and ultimately to decrease diabetes-related complications.

Mobile applications to help adolescents manage their diabetes have been developed. While adolescents are highly engaged in these applications, there are some technological limitations, and those studied have not yet demonstrated a significant effect on A1C.6,7 Text messaging interventions rely on a method of communication in which adolescents are already regularly engaged, with more than half of teens reporting that they text with friends every single day.5 In a study of adolescents with diabetes who use diabetes-related technology, text messaging was the most commonly used technology for disease management.8

Research suggests that text messaging is a useful tool in diabetes education. “Superego” is a 2-way text messaging application tailored to identify barriers to treatment adherence in youth with T1DM. A pilot study resulted in improved self-care in those receiving text messages, and positive usability and satisfaction ratings for the system overall.9 Superego had both web and text message components. Subjects sent text messages over 3 times as often as they logged in to the website. A pilot randomized clinical trial in which subjects received a daily text message regarding healthy lifestyle goals for adolescents and young adults showed information in text messages to be better received compared with paper format, with subjects in the text message group reporting better adherence to nutrition and physical activity goals, and high satisfaction with the text messages received.10 “Sweet Talk,” a text message support system designed to enhance self-efficacy in pediatric T1DM patients, demonstrated increased feelings of self-efficacy and adherence when the application was used over time. Ninety percent of subjects elected to continue receiving the messages after the study period ended.11 In a recent systematic analysis of text messaging interventions,12 Herbert et al suggested that specific behavior change goals be evaluated prior to intervention to ensure success. They also advised that a guiding behavioral theory be chosen prior to implementation of the intervention, and that there should be consideration of the timing and frequency of text messages. The studies reviewed in this analysis generally showed text messaging to be feasible, with high participant satisfaction. Overall, text message reminder systems have been shown to increase participation in daily healthy habits and user-reported adherence to goals in the adolescent T1DM population.

Incentive systems are hailed as strong motivational tools. The gamification theory categorizes point systems for healthy behavior change in the “motivational affordance” category.13 A systematic review showed that incentive systems were the most common theoretical framework used in games for diabetes.14 One example is the “Diabetic Dog Game” on the Nobel Prize website. It teaches children how to manage diabetes through the care of a virtual dog. The better a child cares for the dog in the game, the more points they gain to be used in other parts of the game.15 There are an estimated 1500 commercially available diabetes management applications.16 Specifically, currently in the iTunes App Store, games that use point and reward systems such as “Diapets” and “Pandabetic” are available to download.17 Evidence demonstrating a clinical benefit of the use of these applications is limited.6

MyDiaText™ is a website and text messaging platform created to support behavior change in adolescents with T1DM.18 It was developed in collaboration with the Diabetes Center for Children (DCC) at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia and the University of Pennsylvania School of Nursing and School of Engineering and Applied Sciences, in an effort to focus on diabetes self-care goals, as defined by the AADE7 Self-Care Behaviors,™ and track progress toward these goals. Recommendations from previous studies were taken into consideration during application development and testing.11,12,19 It incorporates input from community engagement sessions to determine the timing and frequency of messages, focuses on target AADE7 Self-Care Behaviors as determined by the user,20,21 and employs the gamification theory by using points to motivate engagement in educational activities on a website. While text message interventions and applications with reward points have been evaluated, there has not been a study published testing a texting intervention that successfully combines the strengths of both paradigms. The purpose of this study was to determine the feasibility and functionality of MyDiaText and to evaluate user satisfaction of the application.

Methods

Research Design

This study was a nonrandomized, prospective, pilot trial to test the feasibility and user interface with MyDiaText, a text message system for 10- to 17-year-old youths with newly diagnosed T1DM. It was performed as a pilot study to ensure technical functionality, compliance, and satisfaction, prior to implementing it as part of a larger randomized controlled trial. In addition, user satisfaction of a text messaging system for youth with T1DM was evaluated. The 4 phases of this study were (1) community engagement—advisory sessions, (2) screening and enrollment, (3) intervention, and (4) follow-up. This study was approved by the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia Institutional Review Board (12-009120). Informed consent was obtained from parents, and assent was obtained from subjects, prior to subject participation. 1

Community engagement—advisory sessions: The DCC engaged 10 youth with diabetes in 2 evening advisory sessions to engender feedback and acceptance of using text messaging for diabetes education and motivation. This was done to actively engage youth in the planning and implementation of MyDiaText, creating community-driven programming. The DCC staff, University of Pennsylvania nursing and public health students, explained the research goals and procedures, underscoring the benefits to participants of learning about their own health. This aspect of the project was aimed to actively engage youth in the community in planning and implementation in order to create community-driven programming. From these sessions, the study team received information regarding the preferred timing and frequency of text messages as determined by potential users of the website.

Screening and enrollment: Potential subjects were screened using the protocol inclusion criteria: diagnosed with T1DM, 10-17 years old, with duration of diabetes greater than 6 months, having completed an Advanced Home Management (AHM) class within the past 6 months, and owning a mobile phone with an unlimited text messaging plan. The AHM class was a 3-hour course offered to patients and parents of newly diagnosed patients. It was offered 4-5 months after diagnosis and was considered a continuation of inpatient diabetes education. Topics covered included disease process, nutrition, exercise, medications, monitoring, and management of complications such as ketonuria. The content of the text messages included in MyDiaText was meant to reinforce these concepts, not introduce them for the first time; completion of the class was considered a requirement to ensure knowledge of basic skills. Subjects who had completed the class were recruited in the diabetes clinic, at a diabetes education class, or verbally over the phone. Parental or guardian informed consent and, if applicable, child assent were obtained in writing prior to any study-related procedures being performed. Once subjects consented, they registered by creating a profile and received a gift card to compensate for their time and effort. A total of 20 subjects were enrolled in a 6-month period. Baseline and demographic characteristics were obtained at enrollment.

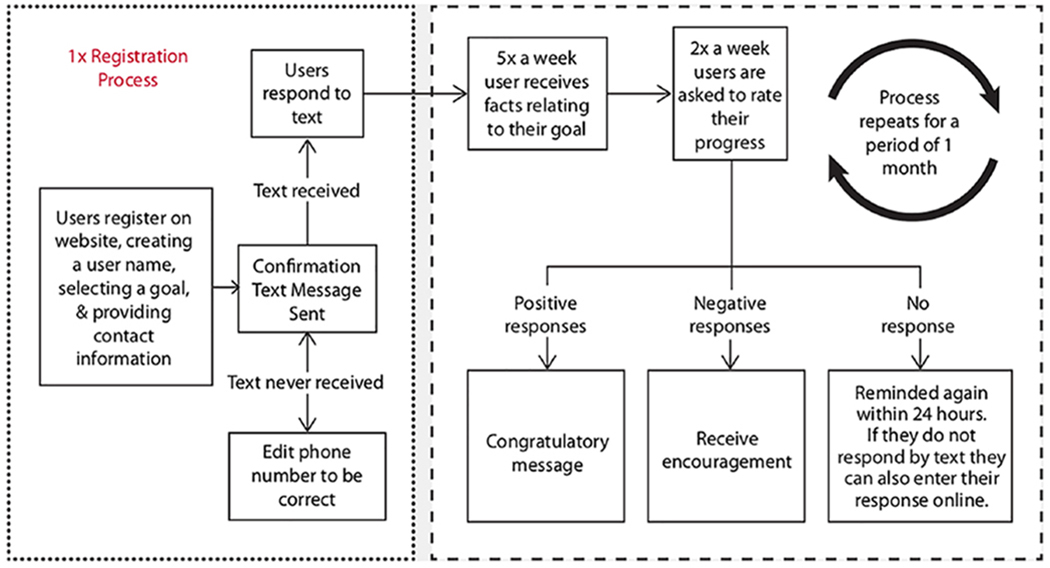

Intervention: Once subjects were registered, a diabetes team member helped them create a profile and choose a diabetes self-management behavioral goal based on the AADE7 Self-Care Behaviors (Table 1). Subjects were asked to provide a phone number to receive daily text messages specifically geared to the identified goal. Text messages included motivational reminders, fun facts, and links for more information related to the identified goal. Once daily, participants received a text message. Twice a week, they were asked to rate their progress. Reminders and congratulatory text messages were sent to participants as depicted in the flowchart in Figure 1. Participants had the opportunity to gain incentive points for completion of online quizzes and review of additional resources. Participants were able to see a running total of the points received on their personal profile. Once a participant reached 100 points, they would receive a certificate. Each patient’s profile was automatically updated with each use for data review by investigators.

Follow-up: After 1 month, participants completed an online questionnaire via SurveyMonkey™ to determine their level of satisfaction. This survey consisted of 5 questions (Table 2), which participants answered by indicating “yes” or “no.” The survey concluded by inviting participants to “Share your comments below.”

Table 1.

AADE7 Self-Care Behaviors21

| Healthy eating |

| Being active |

| Monitoring |

| Taking medication |

| Problem-solving |

| Reducing risk |

| Healthy coping |

Figure 1.

Study procedures.

Table 2.

Patient Satisfaction Survey Results

| Please respond to the following statements (yes/no): | Number of Favorable Responses N = 11 |

|---|---|

| I enjoyed receiving the text messages. | 11 |

| The information in the text messages was helpful. | 11 |

| I would like to continue to receive text messages. | 4 |

| I enjoyed earning reward points. | 10 |

| The frequency of the text messages was the right amount. | 11 |

Setting

Children and adolescents were recruited from the DCC at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia. The outpatient facilities of the DCC were located in the main outpatient clinical facility at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia. The DCC was composed of physicians, nurses, dietitians, behavioral specialists, and research nurse coordinators. The DCC followed approximately 2400 active diabetes patients, with approximately 300 newly diagnosed children with diabetes each year. Over 90% of the children with diabetes seen in the DCC had T1DM.

Technical Platform

The MyDiaText web application was written in C# and JavaScript and leveraged established technologies for user authentication and authorization using Microsoft’s ASP.NET Model-View-Controller (MVC) 4 web framework. SMS text messages services were accessed via a secured connection to Twilio® REST API services, a leading provider for SMS-web integrations. MyDiaText was hosted in Microsoft’s commercial cloud using Windows Azure™ Cloud Services and seamlessly displayed on desktop, notebook, and mobile devices using responsive web design.

As patients sent SMS messages to the MyDiaText registered phone number, Twilio services received the SMS text and communicated with the web application. MyDiaText services interpreted the messages according to anticipated phrases or numerical responses as outlined in Figure 1. Similarly, MyDiaText initiated conversation by sending out messages based on a predetermined schedule to elicit responses from registered patients. If subjects attempted to utilize the application to communicate a clinical concern or question, it sent an automatic reply advising that they contact their provider.

If at any time patients wished to cease communication, Twilio services provided a “STOP” opt-out mechanism by which patients could respond, ending any further communication to that registered phone number. MyDiaText did not attempt to send any unsolicited messages.

Analyses

The primary outcomes for this study were the feasibility and functionality of a text messaging intervention for youth with T1DM. Feasibility was defined as the ability of 100% of users to create a user profile to initiate MyDiaText. Functionality was defined as responding to 2 text messages per week and attaining 100 possible incentive points by completing additional activities on the website. Successful functionality was defined as 80% of subjects responding to 2 text messages per week and earning an average of 60 incentive points, or 60% usage.

The secondary outcome of the study was subject satisfaction. On day 30 of the text messages, participants were asked to complete an online survey, via SurveyMonkey, to provide feedback about the system and determine their level of satisfaction.

Results

Feedback from community engagement sessions recommended that 1 text message be sent per day in the evening. To test the application, a total of 20 subjects (14 male, 6 female) were enrolled (mean age, 13.4 years; 4 identified as black, 10 as white, and 6 as other or race not specified). Over the 30-day study period, a total of 1492 text messages were sent and received, encompassing a variety of AADE7 Self-Care Behaviors (Table 1). The criterion for feasibility was met, as 100% of the subjects were able to create a user profile. The application successfully met the first criterion for functionality, with 86% of enrolled subjects responding to 2 text messages per week. In the analysis of the second criterion for functionality, subjects accumulated 30-100 points, with an average point accumulation of 55. This was below the previously defined average of 60% to meet criteria for functionality. All subjects received daily text messages, responded to “rate your progress” texts, and accrued points during the participation period.

In evaluating the secondary outcomes of satisfaction and evaluation, 55% (11/20) of subjects completed the satisfaction survey administered on day 30 of the study (Table 2). All subjects enjoyed receiving the text messages. All subjects surveyed favorably responded when asked if they enjoyed receiving text messages, if the information in the text messages was helpful, and if the frequency of the text messages was appropriate. Responses to the open-ended concluding question of the survey included “I enjoyed receiving text messages from you; they were helpful thank you,” “These text messages were a good daily reminder to always make good choices,” and “Really helpful to receive text messages and take care of my diabetes.”

Discussion

This study demonstrated the feasibility and functionality of MyDiaText, a text message web application using incentive points to encourage continued use of an educational support tool. Although the average point accumulation fell just below the defined functionality criterion of 60, there were technical limitations specific to point accumulation that affected final point averages. It is likely that the functionality would have been confirmed with a fully functioning point accumulation mechanism. These technical limitations should be addressed and the application retested prior to becoming available for widespread patient use. Overall, the results of this study were consistent with other research supporting the use of mobile health interventions for adolescents with T1DM. Text messaging has been shown to be feasible in children with diabetes, and with high reported satisfaction among participants.22–24

As stated above, MyDiaText experienced technical difficulties during the study period. Out of 7 articles reviewed in the recent systematic analysis by Herbert et al, 4 experienced significant technical problems limiting subject participation and affecting data collection and storage.12 When utilizing the evolving technology of text messaging, there remains the potential for these issues. In addition to more rigorous testing and updating of MyDiaText, the establishment of an infrastructure for continued information technology support is necessary prior to patient use.

A survey administered at the end of the study showed that subjects were satisfied with the intervention and provided positive comments. The responses to the satisfaction questions were positive—for example, all subjects reported that they enjoyed the text messages, the information was helpful, and the frequency of the text messages was the right amount. These results are similar to those of similar pilot tests of a mobile- and web-based health messaging systems.9,25–27 However, our data showed that 63.6% of subjects did not want to continue to receive text messages. This is in contrast to the results of the “Sweet Talk” trial, in which 90% of patients wished to continue receiving messages,11 but concordant with the data from the Computerized Automated Reminder Diabetes System (CARDS) pilot and feasibility study, in which participants’ responses to text messages requesting blood glucose values waned significantly over the 3-month study.19 Systematic reviews of text message interventions to improve health imply that a 2-way text messaging system, in which a healthcare professional answers text messages, may help retain participant interest.12,28

This pilot was designed to evaluate feasibility and functionality. The use of a small sample size provided the opportunity to recognize and repair technical issues, review compliance with the application over time, and assess satisfaction with the text messaging intervention using an electronic survey prior to implementing it on a larger scale as part of a randomized controlled trial. While this feasibility analysis provided valuable information useful for designing a randomized controlled trial, an inherent limitation to the pilot study was its small sample size, preventing hypothesis testing leading to statistically significant conclusions. The sample studied was diverse by race and gender. However, there were some limitations to generalizability. Subjects who received the AHM class were 6 months to 1 year from diagnosis and had completed the full diabetes education curriculum. These patients were not representative of the larger T1DM population as they were still less than a year from diagnosis. Some had just completed the class at the time of recruitment, while others were months out from taking the class. This could represent variability in engagement with the self-care behaviors and, in turn, the text messages. The online survey was administered at the study’s conclusion, but some subjects required multiple attempts at contact and did not complete the survey until 6 months after the study period. This is a potential limitation of the validity of the survey results. The survey did not include questions about why subjects did not want to continue to receive text messages. Future surveys should include queries related to the factors that contribute to the satisfaction of the tool, and interventions tailored appropriately.

MyDiaText is a feasible, functional intervention applying the relevant and frequently utilized technology of text messaging. By addressing minor limitations observed in this initial study, MyDiaText has the potential to serve as an effective intervention to bridge the period of dependence on parents and guardians for diabetes care to independent disease management and selfcare, and to improve glycemic control in adolescents. To design and maintain a functional application, collaboration among healthcare providers and both systems and software engineers is critical. A key implication for diabetes educators is to consider mobile health interventions as part of the diabetes education toolkit. Future randomized controlled studies are needed to determine the impact of a text messaging intervention using MyDiaText on diabetes control and self-care outcomes.

Acknowledgments:

The authors would like to thank the following for their involvement in the creation and execution of MyDiaText™: Robin Lebouf, CRNP; Nancy Hanrahan, PhD, RN; Valerie Cerasuolo, BSE; Kara Hollis, BSE, MSE; John Stuckey, BSE, MBA; and the University of Pennsylvania School of Engineering and Applied Sciences.

Funding: The authors disclose receipt of financial support for the research, authorship, and publication of this article: We gratefully acknowledge funding support from the Community Engagement Research Core, Clinical & Translational Science Award in the Center for Health Behavior Research at the University of Pennsylvania supported by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences of the National Institutes of Health under award number UL1TR001878. The authors also received support from the National Institutes of Health/National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive Kidney Diseases Pediatric Endocrine Fellowship Training Award 2T32DK063688-11-12. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Hamman RF, Bell RA, Dabelea D, et al. The SEARCH for diabetes in youth study: rationale, findings, and future directions. Diabetes Care. 2014;37(12):3336–3344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.American Diabetes Association (ADA). Standard of medical care in diabetes—2017. Diabetes Care. 2017;40(suppl 1):s4–s128.27979887 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Miller KM, Foster NC, Beck RW, et al. Current state of type 1 diabetes treatment in the U.S.: updated data from the T1D exchange clinic registry. Diabetes Care. 2015;38(6):971–978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Borus JS, Laffel L. Adherence challenges in the management of type 1 diabetes in adolescents: prevention and intervention. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2010;22(4):405–411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lenhart BYA, Smith A, Anderson M, Duggan M, Perrin A. Teens, Technology & Friendships: Video Games, Social Media and Mobile Phones Play an Integral Role in How Teens Meet and Interact With Friends. Washington, DC: Pew Research Center; 2015:1–76. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Goyal S, Nunn CA, Rotondi M, et al. A mobile app for the self-management of type 1 diabetes among adolescents: a randomized controlled trial. JMIR mHealth uHealth. 2017;5(6):e82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Castensøe-Seidenfaden P, Husted GR, Jensen AK, et al. Testing a smartphone app (young with diabetes) to improve self-management of diabetes over 12 months: randomized controlled trial. JMIR mHealth uHealth. 2018;6:e141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vaala SE, Hood KK, Laffel L, Kumah-Crystal YA, Lybarger CK, Mulvaney SA. Use of commonly available technologies for diabetes information and self-management among adolescents with type 1 diabetes and their parents: a web-based survey study. Interact J Med Res. 2015;4(4):e24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mulvaney SA, Anders S, Smith AK, Pittel EJ, Johnson KB. A pilot test of a tailored mobile and web-based diabetes messaging system for adolescents. J Telemed Telecare. 2012;18(12):115–118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Markowitz JT, Cousineau T, Franko DL, et al. Text messaging intervention for teens and young adults with diabetes. J Diabetes Sci Technol. 2014;8(5):1029–1034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Franklin VL, Waller A, Pagliari C, Greene SA. A randomized controlled trial of Sweet Talk, a text-messaging system to support young people with diabetes. Diabet Med. 2006;23(12):1332–1338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Herbert L, Owen V, Pascarella L, Streisand R. Text message interventions for children and adolescents with type 1 diabetes : a systematic review. Diabetes Technol Ther. 2013;15(5):362–370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kamel Boulos MN, Gammon S, Dixon MC, et al. Digital games for type 1 and type 2 diabetes: underpinning theory with three illustrative examples. JMIR Serious Games. 2015;3(1):e3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lazem S, Webster M, Holmes W, Wolf M. Games and diabetes: a review investigating theoretical frameworks, evaluation methodologies, and opportunities for design grounded in learning theories. J Diabetes Sci Technol. 2016;10:447–452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.NobelPrize.org The Diabetic Dog Game. http://www.igf.com/diabetic-dog-game. Accessed March 5, 2019.

- 16.Research2Guidance. mHealth App Developer Economics. http://research2guidance.com/mhealth-app-developer-economics/. Accessed March 5, 2019.

- 17.Apple. App Store. https://www.apple.com/ios/app-store/. Accessed March 5, 2019.

- 18.Montgomery KA, Simon R, Lord K, Dougherty J, Hanrahan NP, Lipman TH. MyDiaText™: feasibility and functionality of a text messaging system for youth with type 1 diabetes. Paper presented at: 15 th Annual Diabetes Technology Meeting; October 22-24, 2015; Bethesda, MD. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hanauer DA, Wentzell K, Laffel N, Laffel LM. Computerized Automated Reminder Diabetes System (CARDS): e-mail and SMS cell phone text messaging reminders to support diabetes management. Diabetes Technol Ther. 2009;11(2):99–106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tomsky D, Cypress M, Dang D, Maryniuk M, Peyrot M. AADE7 Self-Care Behaviors. Diabetes Educ. 2008;34:445–449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.AADE7 Self-Care Behaviors for managing diabetes effectively. American Association of Diabetes Educatiors Web site; https://www.diabeteseducator.org/living-with-diabetes/aade7-self-care-behaviors. Accessed March 5, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Herbert LJ, Mehta P, Monaghan M, Cogen F, Streisand R. Feasibility of the SMART project: a text message program for adolescents with type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Spectr. 2014;27(4):265–269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bin-abbas B, Jabbari M, Al-fares A, El-dali A, Al-orifi F. Effect of mobile phone short text messages on glycaemic control in children with type 1 diabetes. J Telemed Telecare. 2014;20:153–156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wangberg SC, Andersson N, Arsand E. Diabetes education via mobile text messaging. Diabetes Educ. 2006;12:55–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Huang H, Li YC, Chou YC. Effects of and satisfaction with short message service reminders for patient medication adherence: a randomized controlled study. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2013;13:127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gerber BS, Stolley MR, Thompson AL, Sharp LK, Fitzgibbon ML. Mobile phone text messaging to promote healthy behaviors and weight loss maintenance: a feasibility study. Health Informatics J. 2010;15(1):1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Markowitz JT, Cousineau T, Franko DL, et al. Text messaging intervention for teens and young adults with diabetes. J Diabetes Sci Technol. 2014;8(5):1029–1034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Service TS, Fjeldsoe BS, Marshall AL, Miller YD. Behavior change interventions delivered by mobile. AMEPRE. 2009;36(2):165–173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]