Abstract

Intrapulmonary teratoma is a rare and little-known disease. The present case was that of an adolescent with recurrent cough and haemoptysis. Chest radiography revealed a mass on the left lung base, and computed tomography (CT) indicated a heterogeneous tumour with a fluid component, soft parts, fat, and calcifications in the left upper lobe. Upper left lobectomy was performed; histopathological findings confirmed a mature pulmonary teratoma.

Keywords: Teratoma, Teratoma mature, Thoracic neoplasms

Introduction

Morh described the first case of teratoma in 1839 [1–3]. To date, the international scientific community has not reached a consensus regarding the number of patients with this condition worldwide [1–5]; some authors even say that they are extremely rare [1, 2, 5–8].

Histopathologically, the teratoma is a true neoplasm that contains tissues derived from the ectodermal, mesodermal, and endodermal germ layers that are not native to the area where they occur. It is classified as mature (benign) or immature (malignant) according to the degree of normality observed in these cells during microscopy [1–5, 8, 9].

Here, we describe the first case of intrapulmonary teratoma reported in Peru. At least five cases have been reported in children under 14 years old in the literature; one of the first cases was presented by Petrunina in 1975 [6–8, 10].

Case report

A 13-year-old male patient with a history of cough, expectoration, and recurrent haemoptysis starting from an unknown period went to the outpatient clinic due to an exacerbation of the condition.

There was no indication of nausea and vomiting, fever, chest pain, dyspnoea, weight loss, trichoptysis, or recurrent infectious respiratory episodes. The physical examination was within the parameters of normality.

The laboratory tests performed on the patient included a complete urine test; alpha-fetoprotein; complete blood count (haematocrit, leukocytes, platelets, and haemoglobin); prothrombin time; thromboplastin time; thrombin time; fibrinogen; blood glucose; blood urea; blood creatinine levels; blood sodium, chloride, and calcium levels; hepatitis B surface antigen and anti-core antibody; HIV-antigens and antibodies; and VDRL, which were all within normal limits.

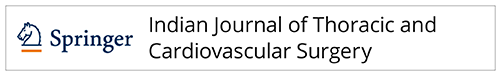

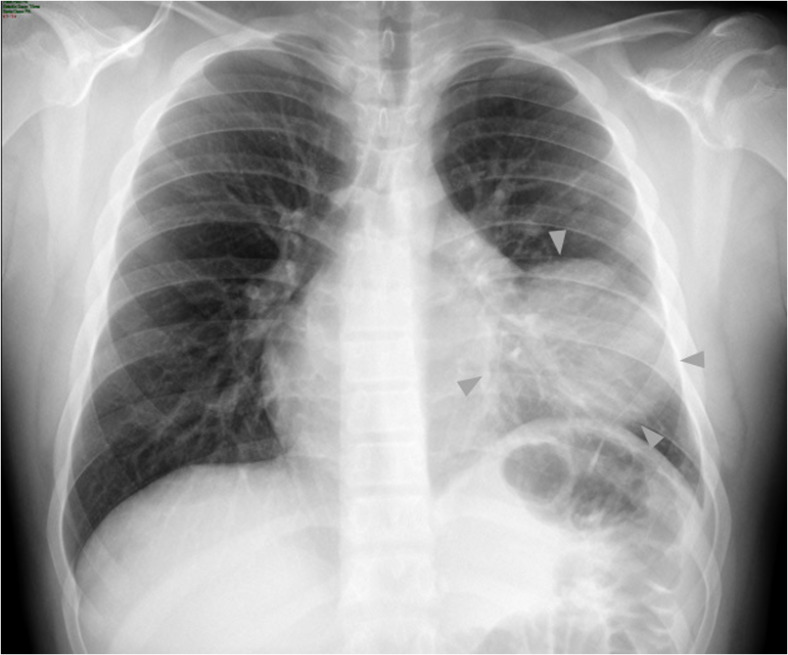

Chest radiography (PA view) revealed a rounded opacity (mass) with regular contours and slightly heterogeneous content; hyperdense areas were noted in its interior, which were suggestive of calcifications; no intralesional air bronchograms were observed. The mass was located on the left lung base adjacent to the cardiac silhouette, with effacement of the silhouette’s contours being noted. The tumour measured 88 × 82 mm and brought about atelectasis and elevation of the left hemidiaphragm (Fig. 1). CT of the thorax with contrast revealed a tumour in the upper left lobe, at the level of the lingula. It contained lobulated and regular contours with heterogeneous content; liquid densities (7–70 UH), fat (− 25 to − 86 UH), soft parts (86 to 100 UH), and calcium (523 to 600 UH) were all present in the tumour (Fig. 2a). Appearing in the periphery of the lesion were rounded and tubular radiolucencies that might have corresponded to bronchi (peripheral translucency sign) and blood vessels coming from the left pulmonary artery and vein (Fig. 2b). It had heterogeneous contrast enhancement, with a few (cystic) areas not being enhanced. It was 89 × 50 × 11 mm in size and had a strong interface with the mediastinum without compromising it, the bony structures, or adjacent soft parts. It was accompanied by alveolar and bronchial compromise (consolidation and atelectasis).

Fig. 1.

Chest radiography (PA view) revealed a rounded opacity (mass). The mass was located on the left lung base adjacent to the cardiac silhouette, with effacement of its contours

Fig. 2.

a CT of the thorax with contrast (axial and coronal view) revealed a tumour with heterogeneous content; liquid densities (---), fat (*), soft parts (+), and calcium (thin arrows) b CT of the thorax (pulmonary view), peripheral translucency sign (solid arrow)

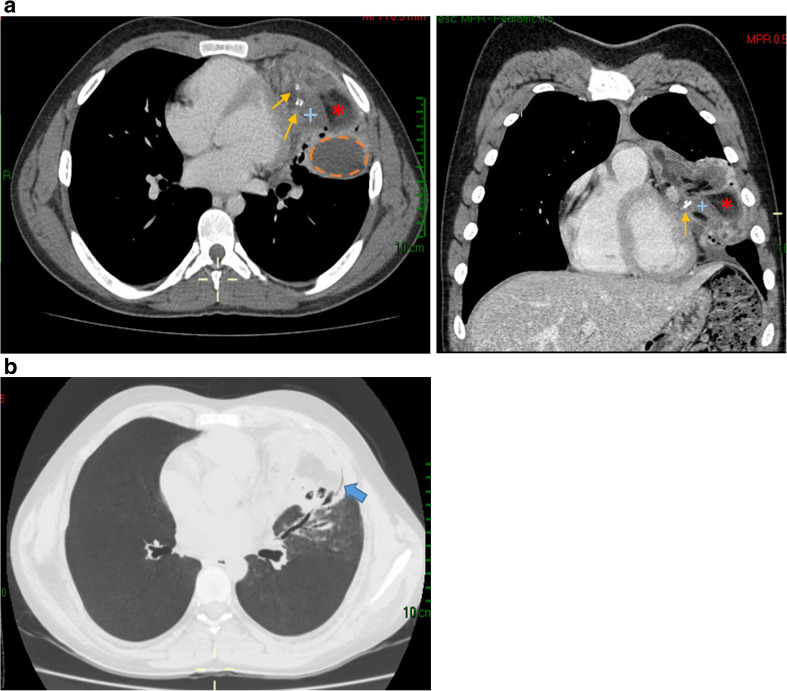

Left upper lobectomy was performed. Macroscopic study of the pathological anatomy of the sample noted an encapsulated clear brown-coloured tumour, which discharged approximately 5 cm3 of sparse colourless liquid in serial sections. Sebaceous material and hairs were observed on the internal surface of the sample. Microscopic examination revealed that the mass contained mature elements of the three germ lines; it possessed stratified squamous epithelium, sebaceous glands, hair follicles (Fig. 3a), adipose tissue (Fig. 3b), smooth muscle, cartilage, respiratory epithelium (Fig. 3c), and pancreatic tissue (Fig. 3d) associated with areas of dystrophic calcifications and foreign body-type inflammatory reaction. Alveolar and interstitial haemorrhage, oedema, and atelectasis were identified in the pulmonary parenchyma adjacent to the lesion.

Fig. 3.

a Sebaceous glands and hair follicles. b Adipose tissue. c Respiratory epithelium. d Pancreatic tissue

Discussion

Most previous studies agreed that the distribution of teratomas by sex is the same for men and women [2, 5, 6, 8], except Abhishek Sawant et al., who claimed that it was more frequent in women [11].

Typical respiratory manifestations are chest pain (52%), haemoptysis (42%), cough (39%), bronchiectasis and post-obstructive pneumonia (16%), and expectoration and trichoptysis (11–13%) [1–6, 8]. The latter is believed to be pathognomonic [1, 2, 4–6, 9]. Our patient was male and presented with cough with expectoration and haemoptysis. No episodes of dyspnoea, fever, weight loss, or trichoptysis were observed.

Other clinical manifestations that have been mentioned in the reviewed articles included fever, weight loss, superimposed lung abscess, and atelectasis [3–6].

Laboratory results such as those of complete blood count, liver function tests, coagulation tests, and urine tests are usually within normal limits [2, 5], except that if the teratoma is malignant, the values of beta human chorionic gonadotropin (ßHCG) and α-fetoprotein will rise as indicators of embryonic carcinoma [6, 7]. In our patient, the results of the routine tests performed were within normal limits.

Fiberoptic bronchoscopy or flexible bronchoscopy is used in multiple diagnostic and therapeutic procedures, being usually indicated when there are suspicions of foreign bodies in the tracheobronchial tree, haemoptysis, and bronchial obstruction due to neoplasms, among others. Fiberoptic bronchoscopy is the procedure of choice in the dynamic visualisation of the airway, and in procedures that do not require sedation. Rigid bronchoscopy also has the same indications; however, its advantage lies in the extraction of larger foreign bodies and other more invasive procedures. Rigid bronchoscopy is usually the technique of choice, for experienced personnel and in children under 12 years of age [12, 13]. However, the usefulness of this procedure in teratomas is limited. Only 67% perceived findings unrelated to the visualisation of the tumour mass but rather with the compressive effects on the bronchi or their rupture [1, 5, 7, 14].

Teratomas are most often located in the left upper lobe and then the upper and middle right lobes. They are least often found in the lower lobes of both lungs [1–11, 14–21].

Chest radiography (PA and Lateral) shows two main findings: masses and cavitary lesions that may be contiguous to the perihilar, paracardiac, and paratracheal regions. In a few cases, calcifications were identified inside the masses or in the cavitary lesions [2, 3, 5–8].

The classic signs in CT for the diagnosis of teratoma are, first, the presence of a heterogeneous mass with variable diameters, containing fat, liquid, soft tissue (with or without presence of calcifications), or a combination of these; second, the mass is located generally in the left upper pulmonary lobe, with a sign of peripheral translucency (visualisation of the bronchi inside the lesion). Peripheral translucency is important because the absence thereof suggests a mediastinal location of the teratoma rather than an intrapulmonary lesion (Fig. 2b). In addition, there may or may not be bronchiectasis, bronchiolectasis, areas of consolidation, or atelectasis [1–6, 8, 9]. One study noted that a crescent-shaped lesion was a distinct presentation [9].

Possible differential diagnoses of masses and thoracic opacities include pulmonary tuberculosis, pulmonary hamartoma, bronchogenic cyst, adenomatoid cystic malformation, intrapulmonary cystic lymphangioma, mediastinal teratoma, and pulmonary leiomyoma. [1–6, 9, 11].

The risk of malignant transformation in intrapulmonary teratomas is a theoretical reality that elicits two opposite positions. Some authors state that an intrapulmonary mature teratoma has a high potential for malignant transformation, as it can be made up of 20–30% of immature tissues (leading to a high risk of the tumour turning into an invasive malignant neoplasm), while others argue that malignant transformation is rare. Indeed, after analysing the literature, we confirmed the existence of only one case of intrapulmonary teratoma becoming malignant, while the remaining cases reported full recoveries showing no changes in their histopathological nature [2, 4, 5, 9, 15–17].

In summary, the most trustworthy theory (and the one to which we subscribe) is that benign intrapulmonary teratomas have a low risk of converting into malignant neoplasms.

Complications related to intrapulmonary teratomas are divided into two groups: (1) complications caused by a rupture of the teratoma affecting intrathoracic structures such as the mediastinum, pericardium, pleural space, lung parenchyma, and tracheobronchial tree and (2) complications not caused by rupture of the teratoma. The first group includes complications such as cardiac tamponade, granulomatous mediastinitis, lipid pneumonia, empyema, pleural effusion, lung abscess, and haemoptysis. The second group includes bronchiectasis, atelectasis, post-obstructive pneumonia, and malignant transformation [1, 2, 5, 9, 15, 18, 19].

The plan for the management of patients is as follows:

Suspected diagnosis: In the case of patients presenting with (1) chest pain; (2) frequent, long-standing haemoptysis; (3) cough and recurring expectoration; (4) a history of recurrent respiratory infections; (4) negative bronchoscopy results or the hairs in the bronchial tree; (5) negative Mantoux test results; (6) laboratory tests ruling out infectious pathology; and (7) classic signs described in the tomography, intrapulmonary teratoma should be suspected [1–9].

Treatment choice and final diagnosis: Surgery is the treatment of choice for intrapulmonary teratoma, which is justified by the suspicion of intrapulmonary teratoma, the size and location of the mass, probability of rupture, potential for malignancy (30% of these tumours are malignant), and complications. Segmentectomy, lobectomy, and pneumonectomy are all appropriate surgical options for these types of patients, which are likely to ensure long survival and full recovery from the illness [1, 3, 8, 9, 14–16, 20, 21]. The probability of surgical success for these cases is high [1–5, 8, 9, 15]. For example, in a study by Khan et al., 13 of 18 patients with suspected intrapulmonary teratoma who underwent surgery had a full recovery [15]. The final diagnosis is based on anatomopathological analysis of the tumour that is surgically resected [1–6, 9, 11, 15].

Follow-up: Once the patient has recovered, he is discharged from the hospital and monitored on an outpatient basis. Follow-up time may vary and will depend on the anatomopathological results (nature of the lesion) defining the tumour prognosis [1–5, 9].

Reviewed cases of benign intrapulmonary teratoma have shown no recurrence, even after a follow-up period of 2 years, revealing an excellent prognosis after the mass has been surgically resected. However, the diagnosis of these tumours is often delayed as these tumours are rare, produce no symptoms during their early stages, and begin with symptoms and signs that result in high morbidity and mortality in their advanced stages [3–5, 15, 20].

Conclusion

In conclusion, teratoma is a disease that is difficult to diagnose due to its rarity, varied clinical presentation, absence of abnormal laboratory results associated with this condition, and nonspecific changes in chest radiography. However, CT is an effective imaging method that helps with the identification of this entity even when the definitive diagnosis is anatomopathological. Surgical resection is the treatment of choice, and the prognosis is good.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors and was in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee.

Informed consent

Informed consent is not needed in this case report.

References

- 1.Villalobos RE, Benedicto J, Villaruel A, Almenario H. A Giant Intrapulmonary Mature Teratoma Located Entirely Within the Lung: An Extraordinary Case. Chest. 2016;150:688A. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2016.08.783. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Akhtar J, Siddiqui MA, Shahid M, Khan NA, Shameem M, Bhargava R. A 24 year-old female with ruptured primary pulmonary teratoma. PNEUMON. 2012;25:243–246. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Faria RA, Bizon JA, Saad Junior R, Dorgan Neto V, Botter M, Saieg MA. Intrapulmonary teratoma. J. Bras Pneumol. 2007;33:612–615. doi: 10.1590/S1806-37132007000500019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ditah C, Templin T, Mandal R, Pinchot JW, Macke RA. Isolated intrapulmonary teratoma. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2016;152:e129–e131. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2016.07.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Macht M, Mitchell JD, Cool C, Lynch DA, Babu A, Schwarz MI. A 31-year-old woman with hemoptysis and an intrathoracic mass. Chest. 2010;138:213–219. doi: 10.1378/chest.10-0173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Saha TK, Roy A, Chattopadhyay A, Roy B, Mondal G. Giant intrapulmonary teratoma in an infant. Hell J Surg. 2015;87:185–187. doi: 10.1007/s13126-015-0205-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Präuer HW, Mack D, Babic R. Intrapulmonary teratoma 10 years after removal of a mediastinal teratoma in a young man. Thorax. 1983;38:632–634. doi: 10.1136/thx.38.8.632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Alper F, Kaynar H, Kantarci M, et al. Trichoptysis caused by intrapulmonary teratoma: computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging findings. Australas Radiol. 2005;49:53–56. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1673.2005.01394.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Barreto MM, Valiante PM, Zanetti G, Boasquevisque CH, Marchiori E. Intrapulmonary mature teratoma mimicking a fungus ball. Lung. 2015;193:443–445. doi: 10.1007/s00408-015-9709-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Petrunina MP, Rymko LP, Kireeva SG. Endobronchial teratoma. Khirurgiia (Mosk). 1975;120–1. [PubMed]

- 11.Sawant AC, Kandra A, Narra SR. Intrapulmonary cystic teratoma mimicking malignant pulmonary neoplasm. BMJ Case Rep. 2012;14:2012. doi: 10.1136/bcr.02.2012.5770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Reynoso FPN, Colín IF. La fibrobroncoscopia. Neumol Cir Tórax. 2006;65:15–25. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bueno BMN. Broncoscopia rígida: indicaciones y ventajas sobre la broncoscopia flexible. Rev Neumosur. 2006;18:43–46. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mondal SK, Dasgupta S. Mature cystic teratoma of the lung. Singapore Med J. 2012;53:e237–e239. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Khan JA, Aslam F, Fatimi SH, Ahmed R. Cough, fever and a cavitary lung lesion-An intrapulmonary teratoma. J. Postgrad. Med. 2005;51:330–331. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vigg A, Khulbey SK, Agarwal SK, et al. Intra-pulmonary teratoma: a rare case. Indian J Chest Dis Allied Sci. 2013;55:155–157. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dasbaksi K, Haldar S, Mukherjee K, Chakraborty U, Majumdar P, Mukherjee P. Intrapulmonary teratoma: Report of a case and review of literature. Asian Cardiovasc Thorac Ann. 2016;24:574–577. doi: 10.1177/0218492315583763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dorterler ME, Boleken ME, Koçarslan S. A giant mature cystic teratoma mimicking a pleural effusion. Case Rep Surg. 2016;2016:1259175. doi: 10.1155/2016/1259175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fatimi SH, Sheikh S. Benign intrapulmonary teratoma. Mayo Clin Proc. 2006;81:1284. doi: 10.4065/81.10.1284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dar RA, Mushtaque M, Wani SH, Malik RA. Giant Intrapulmonary Teratoma: A Rare Case [Internet] Case Rep. Pulmonol. 2011;2011:298653. doi: 10.1155/2011/298653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rana SS, Swami N, Mehta S, Singh J, Biswal S. Intrapulmonary teratoma: An exceptional disease. Ann Thorac Surg. 2007;83:1194–1196. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2006.07.072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]