Abstract

Objective

The correct path after finishing residency in cardiac surgery (CS) has been unclear to most of the young cardiac surgeons. Pursuing a fellowship abroad is by far the most preferred option for many residents after residency. We report the results of the first nationwide survey on the experience of Indian cardiac surgeons who have pursued a fellowship abroad.

Methods

A 10-question Web-based survey was distributed in March, 2018, to all cardiac surgeons in India who have done at least 1 year of fellowship or registrarship in CS abroad. A reminder was sent after 1 month. All responses were verified for genuineness and entirety. A significant 55 responses qualified for survey analysis.

Results

Fifty-five surgeons with a mean experience of 8.1 years after residency and at least 1 year of international training responded to the survey. Australia and New Zealand were the most common countries opted for post-residency training and a majority did a 2-year international fellowship. Most of them were fairly satisfied with protocol learning (4.1/5), research work (3.3/5) and financial support (3.7/5) but not with the surgical hands-on experience (2.9/5). The greatest challenge after the fellowship was to establish an independent practice and get patient referrals. Forty per cent of the surgeons felt that Indian post-residency training could be comparable to international fellowships if the centre is chosen wisely. A few (16%) of them even believed that Indian post-residency training is better than international fellowships.

Conclusions

International fellowships have their own merits and demerits and are to be chosen wisely. In the present situation, Indian post-residency training for basic surgical work is comparable to that of overseas. However, international exposure is recommended for learning advances in cardiac surgical subspecialities like minimally invasive cardiac surgery (MICS), robotic CS, aortic and endovascular techniques and heart failure surgeries.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s12055-018-0736-x) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Cardiac surgery fellowship, International training, Post-residency

When compared with all other surgical specialities, CS appears to have one of the longest learning curves. The residency programme in CS is only able to provide basic knowledge and skills of a much more demanding surgical branch. The training obtained post-residency is crucial in bridging the gap. Therefore, the initial few years after the residency are very important in deciding the future of a young cardiac surgeon’s practice.

We have two kinds of residency programmes in CS in India:

Master of Chirurgiae (M.Ch.) is a 3-year programme accredited by the Medical Council of India (MCI) after 3 years of residency in general surgery.

Diplomate of National Board (DNB) accredited by the National Board of Examinations (NBE) has both options—6-year integrated programme in CS and a 3-year CS course after 3 years of training in general surgery.1

All training programmes run by the NBE are recognised by the MCI and vice versa.1, 2 The residency programme broadly focuses on cardiac, thoracic and vascular surgery. In practice, most residency programmes (especially DNB) still lack focus on paediatric CS and thoracic and vascular surgery. As most of the young surgeons focus on a subspeciality after their residency, fellowships help the young surgeons to choose a specific speciality in CS like paediatric CS, minimally invasive (MICS) and robotic CS and heart transplants as their career.

Because of the scarcity of accredited fellowships in India, most of the young surgeons seek fellowships abroad. For these, the residents have to apply to various institutes individually and fulfil all the necessary formalities needed to practice in that particular country. Countries like the USA need the trainee to clear their medical licencing examination (USMLE). Most other countries need a proof of English proficiency even before applying for a fellowship position. Some countries in Europe insist on obtaining a pass certificate in the country’s native language (e.g. German, French) before applying. Needless to say, this creates a lot of confusion and burden over the young surgeons in the absence of a single portal of information on all these fellowships.

Also, some fellowships are not paid, i.e. candidates are not paid by the institute where they work. They have to be either self-sponsored or sponsored by a government/parent institution. Even obtaining a visa for few countries like the USA is becoming difficult nowadays. After all the efforts and hardships, there always remains an uncertainty about the amount of learning and hands-on training one would get in an international fellowship.

To better assess the perceived advantages, disadvantages and concerns about the international fellowship programmes and to guide future residents, we conducted the first nationwide survey of all cardiac surgeons who have experienced at least a year of fellowship training abroad.

Methods

A 10-question Web-based survey plot (Survey Monkey, SurveyMonkey Enterprise, Los Angeles, CA) was distributed to all cardiac surgeons nationwide on March 10, 2018, by email and various social media platforms. Further, a reminder was sent a month after the initial post. The survey was closed on June 26, 2018. The survey targeted all cardiac surgeons who pursued and finished a minimum of 1 year of training or fellowship abroad after finishing their residency in India. Participation was voluntary and anonymity of all responders was preserved. The survey was subjected to basic statistical analysis. An audit of the data revealed neither duplicate responses nor incomplete responses from any respondent. Only data from completed survey forms was analysed.

The initial questions (1–4) were framed to know the background of the responders and their fellowship (Appendix). Remaining questions focused on the experience of the respondent during the fellowship. Some questions required answers in the form of sentences and hence were expressed in a 4-point Likert response scale (always, often, sometimes and never). The free text responses were quoted and results were analysed and presented in a descriptive manner.

Results

Demographics

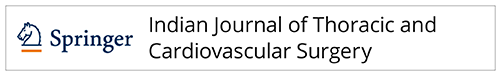

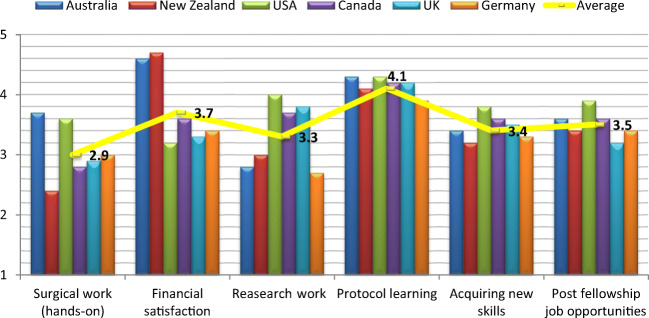

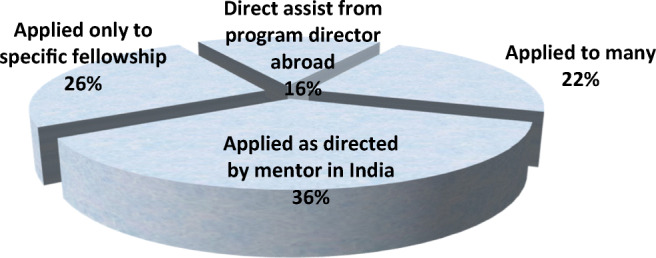

Although there is no prior data on the number of Indian cardiac surgeons with international fellowships, a fairly large response of 55 cardiac surgeons was obtained in our survey. Among these 55 responders (Fig. 1), the average experience after their residency in India was 8.1 years (median 8 years). Of all the countries, Australia was the most common country opted for fellowship followed closely by New Zealand (Fig. 2). These two countries summed up almost half the number of international fellowships by Indian surgeons. The remaining nations were mostly from the Western hemisphere. A majority (31 surgeons, 56.4%) did a 2-year fellowship (mean 1.89 years); 27.3% (15 surgeons) did just 1-year fellowship while the remaining did a 3-year (4 surgeons, 7.3%) or 4-year fellowship (5 surgeons, 9%); 36% chose a centre as guided by their mentor in India (Fig. 3).

Fig. 1.

Distribution of experience of responders in CS after their residency in India

Fig. 2.

Countries where fellowship was pursued by Indian cardiac surgeons

Fig. 3.

Method of choosing the fellowship

During fellowship

When asked about the reasons to go abroad for learning, more than half of them agreed that the three most frequent reasons for opting for an international fellowship were to get work experience (58%), to obtain a tag of international fellowship (51%) and for specific interest in a particular field (50%). Very few surgeons also did a fellowship because of financial (18%) and employment (11%) reasons, for research work (10%) or because their contemporaries did a fellowship outside India (7%). Few responders chose more than one reason for doing a fellowship.

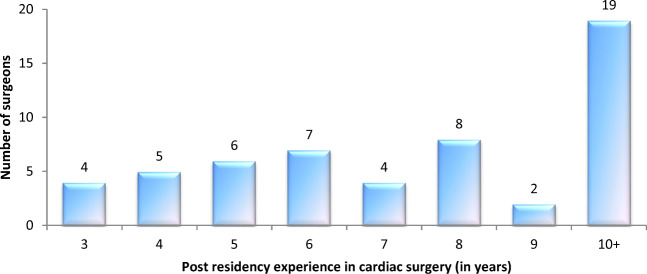

The most noticeable findings in the analysis of experience during the fellowship question were (Fig. 4):

-

(i)

Australia offered the best hands-on training while surprisingly New Zealand-trained surgeons were quite unhappy about the surgical work. The rest of the countries gave them average hands-on experience, but the overall hands-on experience was noticeably not as great as expected.

-

(ii)

Australia and New Zealand offered good financial support whereas trainees in remaining countries were comparatively less satisfied with the monetary issues.

-

(iii)

Experience in research work was significantly better for surgeons who did the fellowship in the USA, Canada and UK compared to other countries.

-

(iv)

Protocol learning was almost similar in all countries and most surgeons were fairly satisfied with it.

-

(v)

US and Canadian fellowships were ranked higher than the others in terms of acquiring new skills.

-

(vi)

Job opportunities after the fellowship were ranked similar by all surgeons though US-trained surgeons seemed to have an edge.

Fig. 4.

Experience during the fellowship (excellent = 5, very good = 4, good = 3, fair = 2, poor = 1)

Most surgeons marked the fulfilment of surgical expectations (Fig. 5) as the biggest challenge outside India. Very few surgeons had language issues or adjustment problems with the mentor.

Fig. 5.

Main challenges during the fellowship (in percentages)

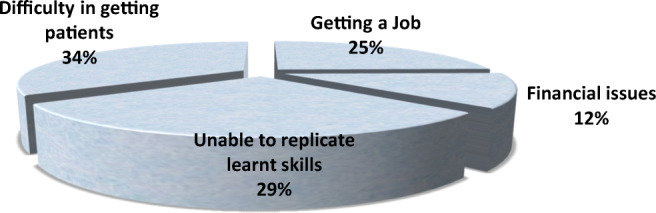

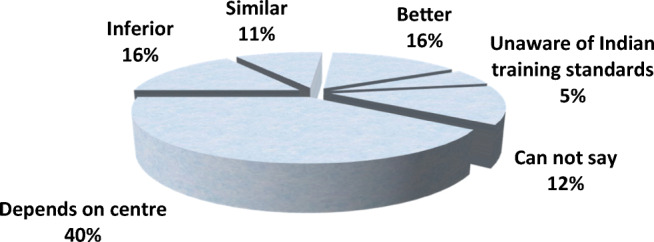

Post-fellowship

Apparently, the greatest challenge (34%) after the fellowship was difficulty in getting patients (Fig. 6). Majority of the surgeons felt that Indian post-residency training is comparable to international training in certain centres (Fig. 7). While 16% of respondents think that Indian post-residency training is inferior to international fellowships, an equal number believe that Indian training is better than international fellowships.

Fig. 6.

Main challenges after the fellowship

Fig. 7.

Opinion about Indian fellowships (post-residency training) compared to international fellowships

Most important advice, facts and words of caution by respondents about international fellowship:

“Training in big volume centres in India nowadays is comparable to international training”

“Going early is beneficial in both aspects- If one wants to settle abroad, it will save years and if one wants to come back to India he/she will have some time to work with seniors here and then become independent. So earlier the better”

“Fellowship is only helpful if you can practice what you have learnt”

“Most places will not allow you to operate independently. Also, not all of the learnt procedures can be replicated”

“Only needed if you want to do something out of the box!”

“Nowadays, our standard is at par with the best in the world but we lack institutional or team practice”

“New Zealand does not seem to be the best place for a fellowship at all. It is just for a name tag”

“Making short focussed trips rather than spending 2–3 years is a better option. Invest your time you would spend abroad in a good centre in India, it will prepare you far better in the future”

“To learn specific areas of interest like aortic/transplant/MICS/mitral”

“First work in India for a couple of years and acquire the required set of skills before you venture out on an overseas fellowship. The kind of surgical opportunities after this is better this way”

“Don’t keep on doing fellowship after fellowship. I went to Texas and was in one institute for three years”

“Best is to get trained in the best centre in India and stick to one place”

“Overseas tag, peer pressure: are myths. Limitation abroad is tying out hands-on. One way of getting trained is to learn gadgetry including robotics”

“Take your family together. Do not try to just fit in; have your own personality and do not become just a door mat to anyone. Publish at least one paper and work hard”

“Not a great option now as centres in India are doing most work”

“I made a mistake of not planning a focussed fellowship in a particular field like MICS or heart failure etc.”

“If the purpose is to return to India- consider Australia or New Zealand. If the plan is to settle abroad- consider USA and head earlier”

“Not mandatory nowadays and if aggressive training in India is pursued, one can go for specific areas of training after settling down”

“Just to learn decision making, integrated work and see novel techniques”

“It’s not for surgical training, but for a broader outlook on life and profession”

“Don’t expect much surgical work”

“Go with a half-filled cup. Be confident and don’t be afraid of what you may face”

“In India, junior cardiac surgeons are underpaid, overworked and have no life except the operating room and home. International fellowships give a work- life balance and bring forth the best inside you”

Most respondents believed that these fellowships should be pursued ideally after 2–3 years of work experience in India. Also, the ideal length of an international training should be at least 1 year and not more than 3 years.

Discussion

To match the rising expectations of patients from a cardiac surgeon in this era of advancing technology, it has become very important for novice cardiac surgeons to have sound knowledge, global exposure, broad-mindedness and logical approach to decision making apart from great surgical skills. The post-residency training is becoming more and more an integral part of the training of a cardiac surgeon, before one starts to practice independently. Therefore, it is very pertinent to learn now about the best path to get trained in CS after finishing the residency in India.

Apart from CS, the residency programmes in India also comprise of thoracic surgery and vascular surgery. Most of the institutes mainly focus on either cardiac or thoracic aspect whereas vascular surgery is usually neglected in the curriculum and practice. While deciding about the future in CS, the residents have options of practising basic CS or to select a particular subspeciality such as paediatric CS, aortic surgery, MICS, mitral surgery and heart failure. Post-residency training plays a pivotal role in moulding their career and deciding about their future practice. Training after residency in India can be either institutional or under a single mentor doing private practice. Very few institutes today offer a recognised fellowship programme in India. So, post-residency training in India still remains arbitrary and subjective. Also, very few centres direct the residents to a specific programme. The other alluring option is opting for an international fellowship. These fellowships come with a package of many promises and compromises. The best way to get trained after residency is therefore difficult to figure out without digging into the unexplored world.

International fellowships in CS are offered by many universities and hospitals across the globe. They either are general fellowships in CS or focus in a specific field of CS. Few of the numerous hurdles in pursuing an overseas fellowship are (i) living away from family, (ii) financial issues, (iii) foreign language, (iv) unknown mentor, (v) cultural and environmental differences, (vi) long waiting periods for fellowship, (vii) complicated and detailed paperwork for medical degree registration, (viii) visa rejections and (ix) recognition of training and degree/diploma in India. Now, the Government of India has to issue a certificate of need for overseas training and this has to be submitted yearly. The government is now clamping down on issue of this certificate. The spectrum of pathology in those countries may not be relevant to our practice in India, e.g. rheumatic heart disease and tuberculosis are rarely seen abroad. Also, uncertainty about the surgical hands-on always remains a major concern.

These fellowships not only add surgical experience in the armamentarium of trainees but also help them in getting exposed to the international world of practice in CS. Residents are also attracted to these fellowships for the tag of an international experience, better lifestyle, financial benefits, better surgical variety, protocol-based practice and above all with the expectation of getting better job opportunities. Also, these build confidence and make “men” out of “boys” and provide a better perspective of life. Some trainees wish to settle down outside India permanently and the fellowship acts as a crucial initial step for them.

Duration of these fellowships usually ranges from 1 to 2 years. They can be further extended on discretion of the institute’s policy and needs. This period is generally sufficient in learning protocols and getting enough surgical hands-on. In our survey, none of the respondents did a fellowship for more than 4 years. Most of the surgeons have advised that international training should be at least 2 years especially if someone is getting trained in a specific field. However, few of them advised to opt for short-term fellowships (less than 6 months), if available, while discouraging just observerships. Long duration or multiple fellowships are usually chosen by candidates who wish to permanently settle overseas.

It is surprising to note that, even though the most common reason for doing an international fellowship was to get surgical work experience, most of the respondents were unsatisfied with the amount of surgical hands-on. Many have further appreciated the training in India and advised to go for a foreign fellowship only for advanced surgical benefits and not to learn basic CS. According to some respondents, international fellowships serve a broader purpose of not merely gaining surgical skills but also in learning protocols and teamwork, and improving personality and lifestyle. However, one always has to weigh the problems against the benefits. The Indian training programme also seems at par, if not ahead, of the international training (at least in basic CS).

Conclusion

To summarise, most of the surgeons who experienced the international fellowships believe that international fellowships not only have their own benefits but also drawbacks. Fellowships in international centres are usually good for learning basic protocols, team effort and research work but may not be satisfying in terms of surgical hands-on experience. International fellowships still hold bigger promises in various subspecialities of CS and should be definitely opted if one wishes to learn these specific subspecialities. In future, Indian fellowships at good centres will certainly play a major role in modelling the post-residency career of young cardiac surgeons.

Electronic supplementary material

(DOCX 14 kb)

References

- 1.Vaithianathan R, Panneerselvam S. Emerging alternative model for cardiothoracic surgery training in India. Med Educ Online. 2013;18 10.3402/meo.v18i0.20961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 2.Medical Council of India. PG medical education regulations; Amended up to Mar 2012. [Cited 2 Jan 2013]. Available from: (Archived by Webcite® at http://www.webcitation.org/6DNJuK2Wo).

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(DOCX 14 kb)