Abstract

Solitary fibrous tumor (SFT) is a rare neoplasm that generally originates in the pleura. Extrapleural locations are rare. In such cases, a definitive preoperative diagnosis is often difficult, because neither radiological nor cytological examinations are exhaustive. Therefore, surgical excision is frequently the only way to reach the correct diagnosis and to provide definitive treatment. The case is here described of a solitary fibrous tumor of the soft tissue in the subscapular area in a 50-year-old male.

Keywords: Solitary fibrous tumor, Extrapleural, Immunohistochemistry

Introduction

Solitary fibrous tumor (SFT) is a rare mesenchymal tumor, characterized by a proliferation of ovoid and fusiform cells which are immune reactive for CD34, and thin wall-ramified blood vessels [1]. They are classified as two types: pleural or extrapleural and are mostly found in the pleura, although up to one third of cases have been reported in extrapleural sites such as the mediastinum, lungs, liver, upper respiratory tract, leg, abdomen, and peritoneum [1].

SFT is benign in more than 70% of cases [1], but current studies have shown a malignancy rate of approximately 50% [2]. Nevertheless, some other studies have shown only a 29% local recurrence (with 50 months median time to event) and 34% metastasis rate (with 44 months median time to event) [3]. Thus, complete surgical excision and long-term follow-up are recommended [3, 4].

The purpose of this report is to raise awareness of SFT as it can mimic more common lesions and cause inappropriate treatment strategies.

Case report

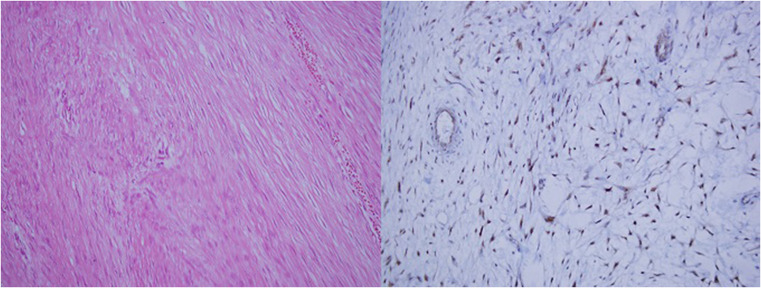

A 50-year-old male presented with a mass on the left side of his back. The history revealed a traffic accident 2 years previously, since when he had experienced intermittent pain, with an increase in these complaints for the last 2 months. In the physical examination, a mass was determined of approximately 30 cm diameter on the left side of the back, extending from the subscapular area to the left axilla. Preoperative ultrasound showed a solid mass of 30 × 22 cm with a homogeneous echo structure. Evaluation with magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed a lesion measuring 30 × 22 cm. The mass had an appearance of sharp borders, heterogenous intensity, evident contrast involvement in the periphery, isointense on T1 images, and hyperintense on T2 images (Fig. 1). There was no intrathoracic extension or relationship with the ribs. The mass had reached an extremely large volume in the short period of 2 months, but as it seemed to be resectable, it was therefore decided to operate. With the first incision, a hard, white mass was exposed in the subscapular area. Frozen section was performed and there were determined to be spindle cell tumors. The whole tumor was completely removed and three peripheral lymph nodes were excised. The mass was seen to have no relationship with the pleura or thoracic cavity (Fig. 2) and had been located only in the subscapular area in soft tissue. There was no invasion of subcostal muscle. The patient was discharged after 3 days with no complications. The tumor had hypocellularity and not much of mitosis (Fig. 3). Three non-metastatic reactive lymph nodes were determined. The immune histochemistry profile was CD99 (+), Bcl 2 (+), S 100(−), CD 31(−), Actin(−), CD 34 (−), and Ki67 index 1% beta catenin (+). The final pathology was reported as solitary fibrous tumor including myxoid changes and spindle cells. No radiotherapy or chemotherapy was administered to the patient. At postoperative 3 years, there has been no recurrence.

Fig. 1.

Preoperative magnetic resonance images

Fig. 2.

Perioperative images

Fig. 3.

Pathological images

Discussion

SFT is a mesenchymal neoplasm that originates from the visceral pleura of the chest wall. It can be benign or malignant, and a small percentage of SFTs (10–15%) behave in a more aggressive way, with local recurrence and/or distant metastasis [5]. Some cases have been reported of extrapleural location, such as the head, neck, brain, prostate, and extremities, but few cases of chest wall localization have been reported in literature [6].

The relationship between morphology and outcomes of SFT is poor. Local recurrence or onset of metastasis depends on the following parameters: histological features, localization (extrathoracic), dimensions (> 10 cm) and most importantly, resectability. Benign SFTs are usually treated with complete surgical excision with a low recurrence rate and good prognosis. Chemotherapy and radiotherapy can be used for a malignant SFT [2, 3].

In the histological criteria published by England et al., a solitary fibrous tumor of the pleura is classified as malignant when1or more of the following criteria are met: a mitotic count of more than 4 mitosis per 10 high-power fields (HPF), presence of necrosis, and presence of nuclear atypia and hypercellularity [7]. These criteria suggest that the tumor can relapse and metastasize. In the current case, there was no necrosis, the tumor was hypocellular, and only one mitosis was seen. Some cells had a distinctive nucleolus with the absence of nuclear atypia.

It may be difficult to differentiate SFT from other spindle cell tumors with hematoxylin-eosin staining alone. Immunohistochemistry can assist to exclude the possibility of epithelial, neural, and myogenous differentiation. SFT cells are immune reactive for CD34 and CD99 and non-reactive for cytokeratin, S100, and desmin [1, 4]. In the current case, CD 99 and Bcl 2 were positive but CD 34 was negative. In view of the clinical diagnosis and pathological features, the possibility of spindle cell lipoma needs to be excluded [1].

In the current case, as the complaint of pain started after trauma, the patient assumed that it was related to the trauma and therefore presented late. However, the trauma occurred 2 years previously and the growth was recent, which first suggested soft tissue sarcoma rather than bone and soft tissue pathologies seen following trauma. No findings could be determined on MRI examination to make a diagnosis of benign or malignant type, suggesting that it was first necessary to diagnose the tissue. However, as the mass had reached such a large size, but was deemed resectable, the resection was performed first. The frozen examination applied during the operation and the pathology examination applied postoperatively confirmed that the approach applied was appropriate. Our classical approach for chest wall tumors, which are located peripherally with no evidence of metastasis or invasion of a vital structure and no suspicion of lymphomatoid diseases, is primary surgical resection without preoperative biopsy, which has a potential risk for seeding of the tumor cells to the skin or other adjacent tissues.

Conclusion

In conclusion, chest wall SFT is extremely rare and diagnosis is challenging. Nevertheless, clinicians should be aware of SFT in different anatomic localizations. SFT lacks specific radiological features, so immune histochemical evaluation is important in the differential diagnosis. Surgical excision is the recommended treatment for SFT. Therefore, in cases of huge soft tissue mass, it is important to keep SFT in mind.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

References

- 1.Fletcher CDM, Unni KK, Mertens F, editors. Pathology and genetics of tumours of soft tissue and bone. 4. Lyon: World Health Organization (WHO) Classification of Tumours, International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) Press; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 2.DeVito N, Henderson E, Han G, et al. Clinical characteristics and outcomes for solitaryfibrous tumor (SFT): a single center experience. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0140362. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0140362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Van Houdt WJ, Westerveld CM, Vrijenhoek JE, et al. Prognosis of solitary fibrous tumors: a multicenter study. Ann Surg Oncol. 2013;20:4090–4095. doi: 10.1245/s10434-013-3242-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vogels RJ, Vlenterie M, Versleijen-Jonkers YM, et al. Solitary fibrous tumor—clinicopathologic, immunohistochemical and molecular analysis of 28 cases. Diagn Pathol. 2014;9:224. doi: 10.1186/s13000-014-0224-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bruzzone A, Varaldo M, Ferrarazzo C, Tunesi G, Mencoboni M. Solitary fibrous tumor. Rare Tumors. 2010;2:e64. doi: 10.4081/rt.2010.e64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mohtarrudin N, Nor Hanipah Z, Mohd Dusa N. Solitary fibrous tumour of the chest wall. Malays J Pathol. 2016;38:61–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.England DM, Hochholzer L, McCarthy MJ. Localized benign and malignant fibrous tumors of the pleura: a clinicopathologic review of 223 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 1989;13:640–658. doi: 10.1097/00000478-198908000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]