Abstract

Background

Some retrospective and in vitro studies suggest that general anesthetics influence breast cancer recurrence and metastasis. We compared the effects of general anesthetics sevoflurane versus propofol on breast cancer cell survival, proliferation and invasion in vitro. The investigation focused on effects in intracellular Ca2+ homeostasis as a mechanism for general anesthetic-mediated effects on breast cancer cell survival and metastasis.

Methods

Estrogen receptor-positive (MCF7) and estrogen receptor-negative (MDA-MB-436) human breast cancer cell lines along with normal breast tissue (MCF10A) were used. Cells were exposed to sevoflurane or propofol at clinically relevant and extreme doses and durations for dose- and time-dependence studies. Cell survival, proliferation and migration following anesthetic exposure were assessed. Intracellular and extracellular Ca2+ concentrations were modulated using Ca2+ chelation and a TRPV1 Ca2+ channel antagonist to examine the role of Ca2+ in mediating anesthetic effects.

Results

Sevoflurane affected breast cancer cell survival in dose-, time- and cell type-dependent manners. Sevoflurane, but not propofol, at equipotent and clinically relevant doses (2% vs. 2 μM) for 6 h significantly promoted breast cell survival in all three types of cells. Paradoxically, extreme exposure to sevoflurane (4%, 24 h) decreased survival in all three cell lines. Chelation of cytosolic Ca2+ dramatically decreased cell survival in both breast cancer lines but not control cells. Inhibition of TRPV1 receptors significantly reduced cell survival in all cell types, an effect that was partially reversed by equipotent sevoflurane but not propofol. Six-hour exposure to sevoflurane or propofol did not affect cell proliferation, metastasis or TRPV1 protein expression in any type of cell.

Conclusion

Sevoflurane, but not propofol, at clinically relevant concentrations and durations, increased survival of breast cancer cells in vitro but had no effect on cell proliferation, migration or TRPV1 expression. Breast cancer cells require higher cytoplasmic Ca2+ levels for survival than normal breast tissue. Sevoflurane affects breast cancer cell survival via modulation of intracellular Ca2+ homeostasis.

Keywords: Anesthetics, Breast, Cancer, Survival, Metastasis, Ca2 +, TRP Channel

Background

Breast cancer is the most common malignancy in women worldwide and a leading cause of cancer-related death in this population. Surgical resection is the primary and curative treatment for patients with localized disease. Multiple factors in the perioperative period including the use of volatile anesthetics and opioids can suppress immune function and facilitate tumor growth [1–4]. Regional analgesics attenuate the surgical stress response leading to hypotheses that they may be favorable over alternative anesthetics [5–7]. In vitro models demonstrate enhanced breast cancer cell function with exposure to an inhalational anesthetic [8]. Serum from patients receiving regional analgesia and propofol inhibited breast cancer cell proliferation to a greater extent than that of patients receiving volatile anesthetics [9]. Retrospective analyses demonstrate the reduced 5-year risk of recurrence of breast cancer with the use of propofol-based total intravenous anesthesia when compared with sevoflurane anesthesia for modified radical mastectomy [10]. Overall, retrospective and cohort clinical studies comparing anesthetic techniques for breast cancer lack concurrence on the benefits of intravenous propofol over inhalational anesthetics [1, 3–5, 7, 11, 12]. These findings call for further investigation into the mechanisms through which anesthetic techniques may alter outcomes for patients with breast cancer.

We focused our study on Ca2+ homeostasis as a mechanism for the action of general anesthetics on breast cancer cell functions. Ca2+ ions are a key mediator of numerous cellular processes including proliferation and apoptosis [13]. Changes in complex Ca2+ signaling pathways and Ca2+ transport proteins contribute to breast tumorigenesis [14, 15]. Transient receptor potential (TRP) channels are a family of ion channels that have been implicated in oncogenic conversion of breast cells [15, 16]. Specifically, transient receptor potential vanilloid 1 (TRPV1) is a Ca2+ transport protein expressed in high levels in various aggressive breast cancer cell lines compared to normal breast epithelial cells [15]. Therapies targeting cellular Ca2+ pathways have demonstrated anti-tumor efficacy in vitro. Volatile anesthetics, such as sevoflurane, isoflurane, and desflurane, and propofol activate Ca2+ receptors [17, 18] including TRPV1, which is sensitized by exposure to inhaled anesthetics [19]. We hypothesized that the highly selective plasma membrane Ca2+ channel, TRPV1, may mediate the observed effects of general anesthetics.

We compared the effects of exposure to two commonly used general anesthetics, sevoflurane and propofol, on breast cancer cell survival, proliferation and migration at equipotent and clinically relevant concentrations in vitro and investigated the role of intracellular Ca2+ homeostasis and TRPV1 Ca2+ channels.

Methods

Reagents

Culture media and BAPTA-AM was obtained from Life Technologies (Carlsbad, CA, USA). Propofol was obtained from Sigma (St. Louis, MO, USA). Sevoflurane was obtained from Midwest Veterinary Supply Inc. (Norristown, PA, USA). MTT (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA), DAPI (Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA) and BrdU (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) assays were used to evaluate breast cancer cells following anesthetic exposure. SB-366791 was obtained from Tocris Bioscience (Minneapolis, MN, USA).

Cell culture

An estrogen receptor-positive human breast adenocarcinoma cell line, MCF7, and an estrogen receptor-negative human breast adenocarcinoma cell line, MDA-MB-436, were used in this study. A normal human breast epithelial line, MCF10A, was used as control. Cell lines were obtained from American Type Culture Collection (Gaithersburg, Maryland, USA). MCF10A cells were cultured in DMEM/F12 Nutrient Mixture supplemented with 5% Horse Serum, EGF 20 ng/ml, insulin 10 μg/ml, hydrocortisone 0.5 mg/ml, cholera toxin 100 ng/ml, MCF7 cells were cultured in MEM with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 10μg/ml insulin. MDA-MB-436 cells were cultured in DMEM with 10% FBS. The mediums were supplemented with 1% penicillin/streptomycin. Cells were maintained in a humidified incubator at 37 °C in 95% air and 5% CO2. The medium was changed every two days and the maximum cell passage was 15. Cells were harvested and added to assay plates before experimentation.

Anesthetic exposure

The three cell lines were exposed to either sevoflurane or propofol in a gas-tight chamber stored in a gastight chamber inside the culture incubator (Bellco Glass, Inc., Vineland, NJ), with humidified 5% CO2–21% O2-balanced N2 (AirGas East, Bellmawr, NJ) going through a calibrated agent-specific vaporizer. All three cell-lines were exposed to either 1, 2% or 4% sevoflurane or 1, 2, and 4 μM propofol for dose-dependent studies. Exposures lasted for 3, 6, and 24 h at each anesthetic concentration for time-dependent studies. Gas-phase concentrations in the gas chamber were verified and maintained at the desired concentration throughout the experiments using an infrared Ohmeda 5330 agent monitor (Coast to Coast Medical, Fall River, MA). Concentrations of 2% sevoflurane and 2 μM propofol and a duration of 6 h were selected for subsequent studies as they represented equipotent clinically relevant exposures [4, 6, 7].

Determination of cell viability

The 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) colorimetric assay was used to assess for cell viability. MTT (0.5 mg/mL) was added to the growth medium in 24-well plates containing either treated or control cells. Following incubation for 3 h at 37 °C, formazan crystals were dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO). Optical density was measured at 590 nm using a SynergyTM H1 microplate reader (BioTek) [8, 9]. The data are presented as percentage of control.

Determination of cell proliferation

Cell proliferation was determined with the 5-bromo-2’deoxyuridine (BrdU) immunostaining assay [8, 9]. Cells were plated onto slides in the medium for 24 h after treatment. BrdU labeling solution (10 μM) was added to the medium and cells were incubated for 3 h. Cells were then fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS and permeabilized using 0.1% Triton X-100 in PBS. The cells were incubated overnight with rat monoclonal anti-5-bromodeoxyuridine primary antibody (1:100) (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas, TX, USA) at 4 °C. The cells were washed with 0.1% Triton X-100 in PBS, and BrdU was detected with fluorescently labeled secondary antibody conjugated with anti-rat IgG (1:1000 for 1 h). The immunostained cells were mounted on microscope slides with Prolong Gold Antifade Reagent containing 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) for visualization of cell nuclei. The imaging of cells were taken using an Olympus BX41TF fluorescence microscope (400×; Olympus, Waltham, Massachusetts, USA) equipped with iVision software (Biovision Technologies, Exton, PA, USA). The number of DAPI-labeled cells and the number of 5-bromodeoxyuridine-labeled cells were counted, and the mean number of cells was calculated from 5 random areas of each coverslip, with 3 to 4 coverslips per condition, from 3 to 4 different cultures. The experimental n equals the number of coverslips. The data are expressed as the percentages of the number of 5-bromodeoxyuridine-positive cells to the total number of cells.

Determination of cell migration

The Transwell Migration Assay was used to determine the invasiveness of cell lines following treatment. A transwell chamber with polycarbonate membrane filters was used for the assay. Cells suspended in serum-free medium were added to the upper chamber and cells suspended in medium containing 10% FBS was added to the lower chamber. A cotton swab was used to remove the cells remained on the upper face of the filters of the membrane after 24 h. The cells that penetrated across the polycarbonate membrane were fixed with 4% formaldehyde for 15 min and stained with 0.1% crystal violet for 20 min. Five random fields were selected; invaded cells were counted under an Olympus BX41TF fluorescence microscope (100x) equipped with iVision software. The experiments were repeated at least three times.

Calcium modulation

In subsequent experiments, we tested the hypothesis that the effects of the general anesthetics are mediated by intracellular Ca2+ signaling. Cells were pre-treated with 5 μM BAPTA-AM Ca2+ chelator for 30 min before exposure to a general anesthetic. To determine the role of extracellular Ca2+ in the effects of general anesthetics, assays were performed using cells incubated in Ca2+ free medium. Cells were pretreated with 10 μM SB-366791, a TRPV1 Ca2+ channel selective antagonist, for 1 h before anesthetic exposure to evaluate the contribution of the channel on cancer cell functions [12, 13].

Western blot

The expression of TRPV1 was evaluated using Western blot analysis. Following anesthetic treatment, the cell culture plate on ice was washed once with ice-cold PBS. After aspiration of PBS, 200 μl of ice-cold lysis buffer (50 mM Tris/HCl, pH 7.8, 150 mM NaCl, 1% Triton X-100) was added to each well and maintained on ice for 5 min. The homogenate was collected with a cell scraper and then centrifuged at 4 °C in a microcentrifuge at 12,000 g for 30 min. The supernatant was gently collected and preserved at − 70 °C for future use. Protein concentration was determined with a bicinchoninic acid kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). For electrophoresis, 40 μg of protein from different samples were loaded on 15% sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis gels and run with a constant current, and then the protein was transferred to nitrocellulose membranes (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA) using a wet transfer system (Bio-Rad). The membranes were blocked with 5% nonfat dry milk dissolved in PBS with 0.2% TWEEN 20 for 1 h at room temperature and incubated overnight at 4 °C with the primary rabbit monoclonal antibody against TRPV1 (1:1000) (Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA, USA) or primary mouse monoclonal antibody against β-actin (1:3000) (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas, TX, USA). This was followed by a wash with secondary antibody conjugated with anti-rabbit and anti-mouse IgG conjugated with horseradish peroxidase (1:10,000) (Bio-Rad) at room temperature for 1 h. The protein on the membranes was detected in a Kodak Image Station 4000MM Pro (Kodak, USA) ECL Prime Western blotting detection reagent (GE Healthcare, UK), and images were acquired with Carestream imaging software (Carestream Health, USA). Signal intensity was quantitatively analyzed with ImageJ software, and the β-actin loading control was used for normalization. n equals the number of wells for each condition.

Statistical analysis

All data were expressed as means ± standard deviation from a minimum of three separate experiments. Statistical analysis was performed using Graphpad Prism 6. Results with p < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Cell viability

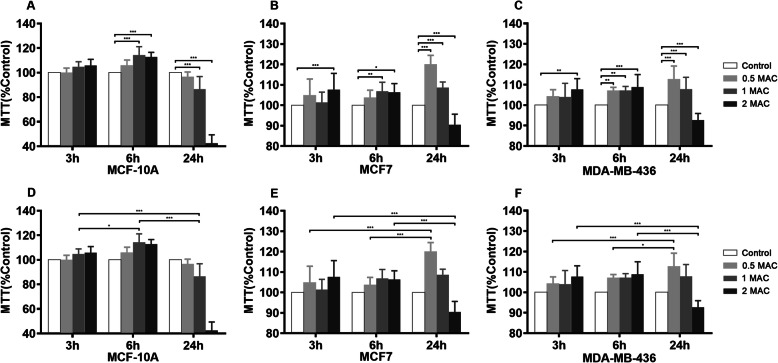

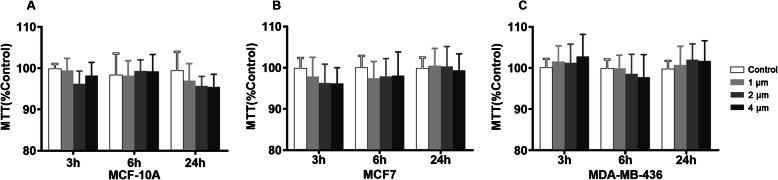

Treatment with sevoflurane impacted breast cancer cell viability as determined by the MTT colorimetric assay in a dose-dependent (Fig. 1a, b, c) and time-dependent (Fig. 1d, e, f) manners. The normal breast tissue cell line (MCF10A) along with the estrogen receptor-positive (MCF7) and estrogen receptor-negative (MDA-MB-436) cell lines demonstrated increased viability following exposure to either 2% or 4% sevoflurane for 6 h when compared to the control group (MCF10A 1MAC&2MAC P < 0.0001, MCF7 1MAC P = 0.0002, 2MAC P = 0.0021, MDA-MB-436 1MAC P = 0.0002, 2MAC P < 0.0001). Sevoflurane treatment duration of 3 h produced a statistically significant effect at a concentration of 4% for the two breast cancer cell lines (MCF7 P < 0.0001, MDA-MB-436 P = 0.0004). A paradoxical reduction in cell viability was observed following exposure to 4% sevoflurane for a prolonged duration of 24 h in all three cell types (MCF10A&MCF7 P < 0.0001, MDA-MB-436 P = 0.0009). Treatment with propofol at equipotent and clinically relevant doses had no significant effect on breast cancer cell viability (Fig. 2).

Fig. 1.

Sevoflurane modulates breast cancer cell survival in a dose- and time-dependent manner. a, b, c Dose-dependence relationships of sevoflurane exposure on breast cancer survival in vitro. d, e, f Time-dependence relationships of sevoflurane exposure on breast cancer cell survival in vitro. Exposure to sevoflurane at clinically relevant concentrations of 2 and 4% for 6 h significantly promoted breast cancer survival in normal breast cells (MCF10A) along with estrogen receptor-positive (MCF7) and estrogen receptor-negative (MDA-MB-436) breast adenocarcinoma cells. Treatment with 4% sevoflurane produced a statistically significant increase in cell survival after 3 h in both breast cancer cell types. Exposure to low-dose sevoflurane (1%) for an extended duration of 24 h also increased survival when compared to treatment for 3 and 6 h for the breast adenocarcinoma lines. Paradoxically, extreme exposure to 4% sevoflurane for 24 h reduced cell survival in all cell lines. All data are expressed as means ± SD from at least three separate experiments in duplicate or triplicate and analyzed by two-way ANOVA followed by Tukey multiple comparison tests. * P < 0.5, ** P < 0.01, *** P < 0.001, **** P < 0.0001

Fig. 2.

Exposure to propofol does not affect breast cancer cell survival. Dose- and time-dependence experiments with exposure to 1, 2, and 4 μM propofol for 3, 6, and 24 h demonstrated that propofol does not modulate cell survival in normal breast tissue (a) or breast adenocarcinoma lines (b, c)

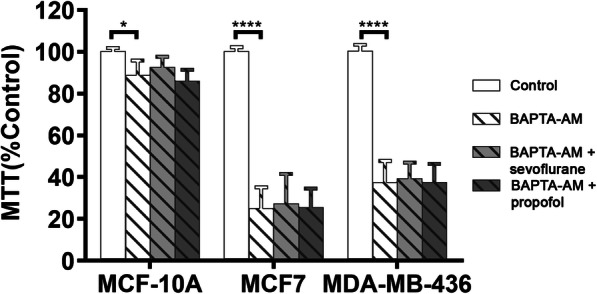

Calcium homeostasis and cell viability

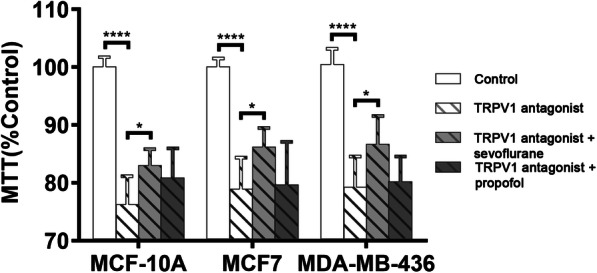

To evaluate the role of intracellular Ca2+ homeostasis in the augmentation of breast cancer cell viability by sevoflurane, we modulated intracellular and extracellular Ca2+ concentrations. For these experiments, 2% sevoflurane and 2 μM propofol were chosen as equipotent and clinically relevant anesthetic concentrations along with a treatment duration of 6 h. Increased cell viability was demonstrated following treatment with 2% sevoflurane for 6 h when compared to the control (MCF10A p < 0.0001, MCF7 & MDA-MB-436 p = 0.0002). Treatment with 2 μM propofol had no significant effect on cell viability. The addition of BAPTA-AM Ca2+ chelator dramatically reduced the viability of MCF7 and MDA-MB-436 breast cancer cell lines (MCF7 & MDA-MB-436 p < 0.0001) but did not impact that of the MCF10A normal breast tissue line (Fig. 3). To elucidate the mechanism of sevoflurane on breast cancer cell viability, we studied the role of cell membrane Ca2+ channel TRPV1 activation on cell survival. Similar to the prior Ca2+ modulation techniques, the highly specific TRPV1 channel antagonist SB-366791 reduced cell viability in all three cell lines (MCF10A, MCF 7 & MDA-MB-436 p < 0.0001). Concurrent treatment with sevoflurane and the TRPV1 channel antagonist partially reversed this reduction in cell survival (MCF 10A p = 0.022, MCF7 p = 0.0148, MDA-MB-436 p = 0.0128) (Fig. 4). The use of propofol with SB-366791 did not impact cancer cell viability when compared to the use of SB-366791 alone.

Fig. 3.

Decreased cytosolic Ca2+ concentrations reduce breast cancer cell survival. Chelation of cytosolic Ca2+ with BAPTA-AM dramatically reduced cell survival in both breast cancer lines but not in normal breast tissue. The use of general anesthetics sevoflurane and propofol did not alter this effect. Data represents means ± SD from at least 9 repeats of 3 separate experiments and was analyzed by two-way ANOVA followed by Turkey multiple comparison tests. * P < 0.05, **** P < 0.0001

Fig. 4.

Sevoflurane partially reverses the reduction in cell survival by TRPV1 channel antagonism. Inhibition of Ca2+ influx through the TRPV1 receptor Ca2+ channel with the selective antagonist SB-366791 reduces cell survival in all three cell lines. Concomitant use of sevoflurane, but not propofol, partially reversed this effect. Data represents means ± SD from at least 9 repeats of 3 separate experiments and was analyzed by two-way ANOVA followed by Turkey multiple comparison tests. * P < 0.05, **** P < 0.0001

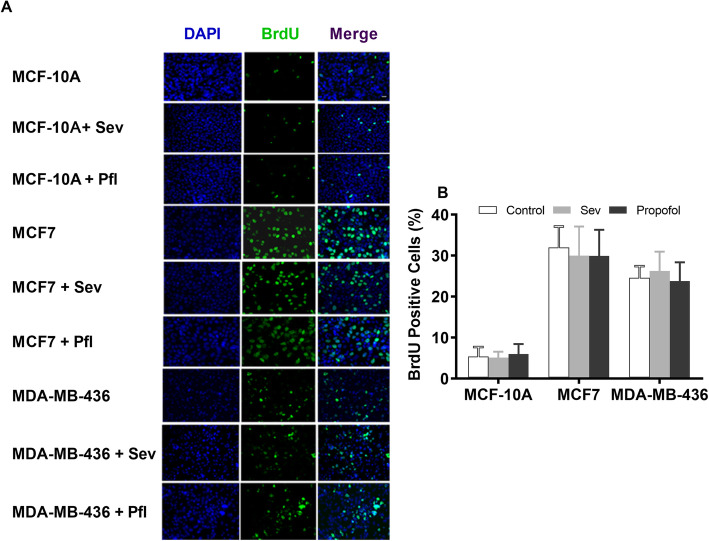

Cell proliferation

The effects of a 6-h exposure to equipotent doses of sevoflurane (2%) and propofol (2 μM) on breast cell proliferation were evaluated using immunostaining with diamino-2-phenylindole (DAPI, blue) and 5-bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU, green) (Fig. 5). Quantitative analysis of stained cells demonstrated no significant difference in the percentage of BrdU-positive cells between two general anesthetics among all three cell lines.

Fig. 5.

Effects of general anesthetics (GAs) on breast cancer cell proliferation. a Representative images showing the double immunostaining of cell nuclei with 4′,6-diamino-2-phenylindole (DAPI, blue, arrows) and 5-bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU, green, arrows) in control breast cancer cells (MCF 10A), estrogen receptor-positive (MCF 7) and negative (MDA-MB-436) breast cancer cells with and without sevoflurane (2%) and propofol (2 μM), at equipotent dose for 6 h. Scale bar = 100 μm. b Quantitative analysis of the effect of a 6-h exposure to an equipotent dose of sevoflurane (2%) vs. propofol (2 μM) on cell proliferation. Exposure to 2% sevoflurane and 2 μM propofol does not affect the percentage of cell proliferation (% of BrdU-positive cells) among all three cell lines (n = 12). All data are expressed as means ± SD from at least three separate experiments in duplicate or triplicate and analyzed by one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey multiple comparison tests

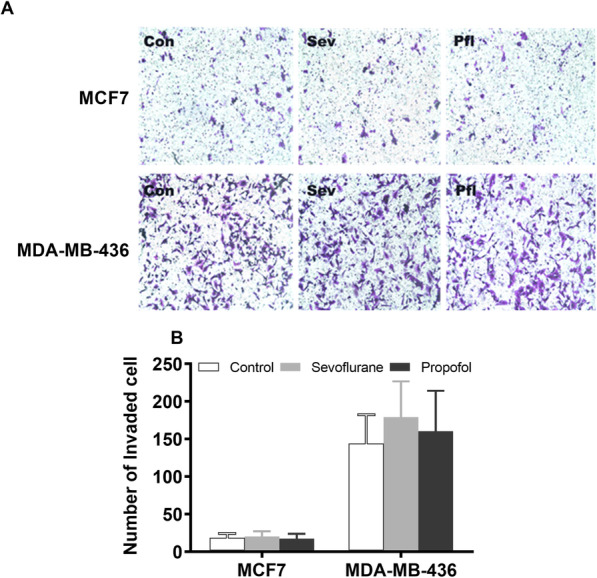

Cell invasion

The Transwell Migration Assay was used to determine the invasiveness of breast cancer cell lines following exposure to general anesthetics (Fig. 6). The estrogen receptor-negative MDA-MB-436 has a greater invasion potential that the estrogen receptor-positive MCF7. Treatment with equipotent doses of sevoflurane (2%) and propofol (2 μM) for 6 h did not affect the invasion capacity in either of two breast cancer cell lines.

Fig. 6.

Effects of general anesthetics (GAs) on breast cancer cell migration. a Representative images of the Transwell Migration Assay used to determine the invasiveness of estrogen receptor-positive (MCF 7) and negative breast cancer cell lines (MDA-MB-436). b MDA-MB-436 exhibits greater migration potential thanMCF7. Exposure to equipotent sevoflurane (2%) and propofol (2 μM) did not affect migration in either breast cancer cells. All data are expressed as means ± SD from at least repeats of 3 separate experiments in duplicate or triplicate wells, and analyzed by one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey multiple comparison tests

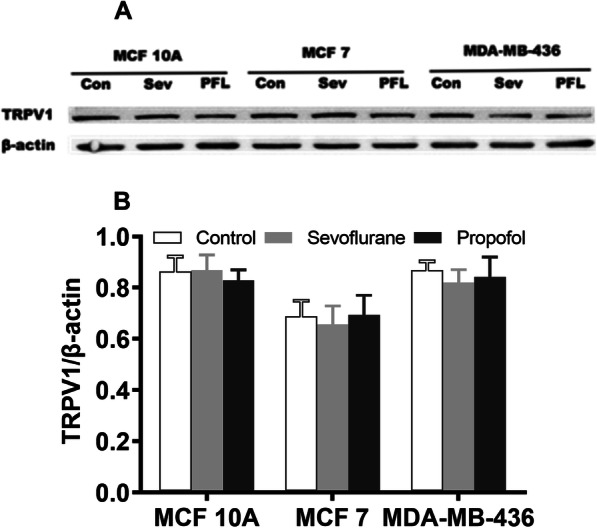

TRPV1 channel protein expression

As the TRPV1 channel plays an important role in tumor cell survival, proliferation and migration, we examined the changes in TRPV1 protein levels. Expression of the cell membrane Ca2+ channel TRPV1 was quantified using Western blot (Fig. 7). Exposure to the general anesthetics (sevoflurane vs. propofol) did not significantly alter TRPV1 expression in the three cell lines.

Fig. 7.

Effect of general anesthetics on TRPV1 channel expression. a TRPV1 protein expression in all three cell lines was quantified using the cropping of the Western blot. The β-actin was used as a loading control. Full-length blots are presented in Supplementary Fig. 8. b Treatment with equipotent doses of sevoflurane (2%) and propofol (2 μM) for 6 h did not affect TRPV1 protein expression in any of the three cell lines. All values shown are means ± SD of triplicate repeats from three separate experiments and were analyzed by one-way ANOVA

Discussion

Anesthetic technique may influence long-term recurrence and outcomes following surgical interventions for breast cancer. The emerging research on dysregulated Ca2+ signaling in breast oncogenesis along with anesthetic modulation of Ca2+ channels led to the hypothesis that Ca2+ homeostasis may be a potential mechanism. This study aimed to examine the effects of general anesthetics on breast cancer cell function and to characterize the role of Ca2+ homeostasis in this relationship. Sevoflurane increases breast cancer cell survival at clinically relevant concentrations and durations in both estrogen receptor-positive and negative breast cancer cells in vitro while propofol has no such effect. Exposure to sevoflurane at extreme concentrations and durations paradoxically decreases the survival of breast adenocarcinoma cells. Neither sevoflurane nor propofol has significant effects on proliferation, migration or TRPV1 protein expression in the studied cell lines.

In various kinds of neurons, general anesthetics at low concentrations for short durations promote cell survival, proliferation and neurogenesis by adequate or physiological increase of cytosolic Ca2+ concentrations via activation of InsP3 receptor (InsP3R) Ca2+ channel and subsequent Ca2+ release from the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) [20–23] or Ca2+ influx from extracellular space [24], thus resulting in preconditioning cytoprotection [25] or promoting autophagy [18]. However, general anesthetics at high concentrations for prolonged duration cause cell death directly by pathological Ca2+ release from the ER via excessive activation of InsP3R [17, 20] or abnormal Ca2+ influx from extracellular space. Similar to the dual effects of general anesthetics on cell survival in most neurons, the results from this study suggest that commonly used general anesthetic sevoflurane at low concentrations for short durations also promotes breast cancer survival, while at high concentrations for prolonged durations causes damage to these cells. This dual effect of cytoprotection versus cytotoxicity depends on exposure levels. Similar to the results of neuronal studies [21, 23, 24], the inhalational anesthetic sevoflurane was a more potent modifier of breast cancer cell survival in vitro than propofol. These results suggest general anesthetics have similar effects on cell survival in different cell types.

In various in vitro and in vivo models, sevoflurane has been shown to either promote [8, 26] or inhibit [27] breast cancer cell proliferation and/or metastasis. Compared to sevoflurane, propofol has been demonstrated to be less likely to promote breast cancer cell proliferation [26] and reduce the risk of recurrence during the initial 5 years after modified radical mastectomy [10]. The results from the present study suggest that propofol at clinically relevant concentrations and durations is less likely to promote breast cancer survival than sevoflurane, which is consistent with previous findings that propofol decreases the risk of proliferation and tumor recurrence [10, 26]. Our dose- and time-dependence experiments also revealed that exposure to sevoflurane at a high concentration for an extended period paradoxically and dramatically decreased cell survival. Prior physiologic studies demonstrate that prolonged rises in intracellular Ca2+ trigger apoptosis due to disruptions in complex regulatory pathways [28]. Further studies are necessary to confirm these findings and guide clinical practice.

Changes in cytosolic Ca2+ concentration via activation of some transient receptor potential (TRP) Ca2+ channels regulate cancer cell survival, apoptosis and metastasis [29]. Overexpression of TRPV1 channels in some breast cancer cell lines may contribute to breast cancer cell processes important in tumor progression such as angiogenesis [14]. Chelation of cytosolic Ca2+ dramatically reduces survival in breast cancer cells when compared to normal breast cells. This suggests that a high baseline cytosolic Ca2+ concentration is needed to support breast cancer cell survival and growth, although excessive activation of TRPV1 by exogenous agonists leads to cancer cell apoptosis [30]. Blocking Ca2+ influx through the TRPV1 ion channel results in a similar degree of decline in cell survival of all three cell lines in vitro. Concomitant use of sevoflurane, but not propofol, partially reverses this effect of TRPV1 antagonism. These findings suggest that changes in intracellular Ca2+ homeostasis play an important role in the general anesthetic-mediated enhancement of breast cancer cell survival. Specifically, the TRPV1 channel is a potential site of action of sevoflurane in altering intracellular Ca2+ levels leading to increased survival of breast cancer cells. Additional studies are needed to further elucidate the mechanism of the observed effect. While such in vitro studies help us elucidate the mechanisms that underlie anesthetic effects on breast cancer cell function, it is important to evaluate these relationships with animal studies and prospective randomized control trials.

In summary, exposure to sevoflurane, but not propofol, at clinically relevant concentrations and durations increased the survival of breast cancer cells in vitro. Breast cancer cells require higher cytoplasmic Ca2+ levels to maintain survival than normal breast tissue. Sevoflurane partially reverses the decrease in survival caused by TRPV1 antagonism suggesting that sevoflurane may enhance breast cancer cell survival through the activation of TRPV1 Ca2+ channels.

Conclusion

Sevoflurane, but not propofol, at clinically relevant concentrations and durations increased the survival of breast cancer cells partially through the activation of TRPV1 Ca2+ channels. Breast cancer cells require higher cytoplasmic Ca2+ concentrations to maintain survival than normal breast tissue.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgments

We appreciate the valuable discussion and statistical analysis assistance from Maryellen Eckenhoff, Roderic Eckenhoff from the Department of Anesthesiology, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

Abbreviations

- TRPV1

Transient receptor protein V1

- MTT

3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide

- DMSO

dimethyl sulfoxide

- BrdU

5-bromo-2’deoxyuridine

Authors’ contributions

Conceived and designed the study and wrote the manuscript: HW, MV. Performed: XD, MV, BW, Analyzed and interpreted the data: MV, GL, DG, BW. All authors have read and approved the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by grants to HW from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences (R01GM084979); National Institute on Aging (R01AG061447). Also supported by Medical Student Anesthesia Research Fellowship to MV from the Foundation of Anesthesia Education and Research.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was not submitted to the animal institutional ethics committee.

Experiments were performed with permanent breast cancer cell lines which were commercially obtained from ATCC (American Type Cell Culture).

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

No authors declare competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1186/s12871-020-01139-y.

References

- 1.Enlund M, Berglund A, Andreasson K, Cicek C, Enlund A, Bergkvist L. The choice of anaesthetic--sevoflurane or propofol--and outcome from cancer surgery: a retrospective analysis. Ups J Med Sci. 2014;119(3):251–261. doi: 10.3109/03009734.2014.922649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Huitink JM, Heimerikxs M, Nieuwland M, Loer SA, Brugman W, Velds A, Sie D, Kerkhoven RM. Volatile anesthetics modulate gene expression in breast and brain tumor cells. Anesth Analg. 2010;111(6):1411–1415. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0b013e3181fa3533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lukoseviciene V, Tikuisis R, Dulskas A, Miliauskas P, Ostapenko V. Surgery for triple-negative breast cancer- does the type of anaesthesia have an influence on oxidative stress, inflammation, molecular regulators, and outcomes of disease? J BUON. 2018;23(2):290–295. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wall T, Sherwin A, Ma D, Buggy DJ. Influence of perioperative anaesthetic and analgesic interventions on oncological outcomes: a narrative review. Br J Anaesth. 2019;123(2):135–150. doi: 10.1016/j.bja.2019.04.062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cassinello F, Prieto I, del Olmo M, Rivas S, Strichartz GR. Cancer surgery: how may anesthesia influence outcome? J Clin Anesth. 2015;27(3):262–272. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinane.2015.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Deegan CA, Murray D, Doran P, Moriarty DC, Sessler DI, Mascha E, Kavanagh BP, Buggy DJ. Anesthetic technique and the cytokine and matrix metalloproteinase response to primary breast cancer surgery. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2010;35(6):490–495. doi: 10.1097/AAP.0b013e3181ef4d05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Exadaktylos AK, Buggy DJ, Moriarty DC, Mascha E, Sessler DI. Can anesthetic technique for primary breast cancer surgery affect recurrence or metastasis? Anesthesiology. 2006;105(4):660–664. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200610000-00008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ecimovic P, McHugh B, Murray D, Doran P, Buggy DJ. Effects of sevoflurane on breast cancer cell function in vitro. Anticancer Res. 2013;33(10):4255–4260. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Deegan CA, Murray D, Doran P, Ecimovic P, Moriarty DC, Buggy DJ. Effect of anaesthetic technique on oestrogen receptor-negative breast cancer cell function in vitro. Br J Anaesth. 2009;103(5):685–690. doi: 10.1093/bja/aep261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee JH, Kang SH, Kim Y, Kim HA, Kim BS. Effects of propofol-based total intravenous anesthesia on recurrence and overall survival in patients after modified radical mastectomy: a retrospective study. Korean J Anesthesiol. 2016;69(2):126–132. doi: 10.4097/kjae.2016.69.2.126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Oh CS, Lee J, Yoon TG, Seo EH, Park HJ, Piao L, Lee SH, Kim SH. Effect of equipotent doses of Propofol versus Sevoflurane anesthesia on regulatory T cells after breast Cancer surgery. Anesthesiology. 2018;129(5):921–931. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0000000000002382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sessler DI, Pei L, Huang Y, Fleischmann E, Marhofer P, Kurz A, Mayers DB, Meyer-Treschan TA, Grady M, Tan EY, et al. Recurrence of breast cancer after regional or general anaesthesia: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet (London, England) 2019;394(10211):1807–1815. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)32313-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wu TT, Peters AA, Tan PT, Roberts-Thomson SJ, Monteith GR. Consequences of activating the calcium-permeable ion channel TRPV1 in breast cancer cells with regulated TRPV1 expression. Cell Calcium. 2014;56(2):59–67. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2014.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.So CL, Milevskiy MJG, Monteith GR. Transient receptor potential cation channel subfamily V and breast cancer. Lab Investig. 2020;100(2):199–206. doi: 10.1038/s41374-019-0348-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.So CL, Saunus JM, Roberts-Thomson SJ, Monteith GR. Calcium signalling and breast cancer. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2019;94:74–83. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2018.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yang Z, Yue Z, Ma X, Xu Z. Calcium homeostasis: a potential vicious cycle of bone metastasis in breast cancers. Front Oncol. 2020;10:293. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2020.00293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Joseph JD, Peng Y, Mak DO, Cheung KH, Vais H, Foskett JK, Wei H. General anesthetic isoflurane modulates inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor Ca2+ channel opening. Anesthesiology. 2014;121(3):528–537. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0000000000000316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ren G, Zhou Y, Liang G, Yang B, Yang M, King A, Wei H. General anesthetics regulate autophagy via modulating the inositol 1,4,5-Trisphosphate receptor: implications for dual effects of Cytoprotection and cytotoxicity. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):12378. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-11607-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cornett PM, Matta JA, Ahern GP. General anesthetics sensitize the capsaicin receptor transient receptor potential V1. Mol Pharmacol. 2008;74(5):1261–1268. doi: 10.1124/mol.108.049684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wei H, Liang G, Yang H, Wang Q, Hawkins B, Madesh M, Wang S, Eckenhoff RG. The common inhalational anesthetic isoflurane induces apoptosis via activation of inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptors. Anesthesiology. 2008;108(2):251–260. doi: 10.1097/01.anes.0000299435.59242.0e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhao X, Yang Z, Liang G, Wu Z, Peng Y, Joseph DJ, Inan S, Wei H. Dual effects of isoflurane on proliferation, differentiation, and survival in human neuroprogenitor cells. Anesthesiology. 2013;118(3):537–549. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e3182833fae. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Peng J, Drobish JK, Liang G, Wu Z, Liu C, Joseph DJ, Abdou H, Eckenhoff MF, Wei H. Anesthetic preconditioning inhibits isoflurane-mediated apoptosis in the developing rat brain. Anesth Analg. 2014;119(4):939–946. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0000000000000380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Qiao H, Li Y, Xu Z, Li W, Fu Z, Wang Y, King A, Wei H. Propofol affects Neurodegeneration and neurogenesis by regulation of autophagy via effects on intracellular Ca2+ homeostasis. Anesthesiology. 2017;127(3):490–501. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0000000000001730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yang M, Wang Y, Liang G, Xu Z, Chu CT, Wei H. Alzheimer's disease Presenilin-1 mutation sensitizes neurons to impaired autophagy flux and Propofol neurotoxicity: role of Ca2+ Dysregulation. J Alzheimers Dis. 2019;67(1):137–147. doi: 10.3233/JAD-180858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bickler PE, Zhan X, Fahlman CS. Isoflurane preconditions hippocampal neurons against oxygen-glucose deprivation: role of intracellular Ca2+ and mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling. Anesthesiology. 2005;103(3):532–539. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200509000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yan T, Zhang GH, Wang BN, Sun L, Zheng H. Effects of propofol/remifentanil-based total intravenous anesthesia versus sevoflurane-based inhalational anesthesia on the release of VEGF-C and TGF-beta and prognosis after breast cancer surgery: a prospective, randomized and controlled study. BMC Anesthesiol. 2018;18(1):131. doi: 10.1186/s12871-018-0588-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liu J, Yang L, Guo X, Jin G, Wang Q, Lv D, Liu J, Chen Q, Song Q, Li B. Sevoflurane suppresses proliferation by upregulating microRNA-203 in breast cancer cells. Mol Med Rep. 2018;18(1):455–460. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2018.8949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Giorgi C, Baldassari F, Bononi A, Bonora M, De Marchi E, Marchi S, Missiroli S, Patergnani S, Rimessi A, Suski JM, et al. Mitochondrial Ca(2+) and apoptosis. Cell Calcium. 2012;52(1):36–43. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2012.02.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shapovalov G, Lehen'kyi V, Skryma R, Prevarskaya N. TRP channels in cell survival and cell death in normal and transformed cells. Cell Calcium. 2011;50(3):295–302. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2011.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Naziroglu M, Cig B, Blum W, Vizler C, Buhala A, Marton A, Katona R, Josvay K, Schwaller B, Olah Z, et al. Targeting breast cancer cells by MRS1477, a positive allosteric modulator of TRPV1 channels. PLoS One. 2017;12(6):e0179950. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0179950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request