Abstract

Background

To externally validate the Prediction for ASCVD Risk in China (PAR) risk equation for predicting the 5-year atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) risk in the Uyghur and Kazakh populations from rural areas in northwestern China and compare its performance with those of the pooled cohort equations (PCE) and Framingham risk score (FRS).

Methods

The final analysis included 3347 subjects aged 40–74 years without CVD at baseline. The 5-year ASCVD risk was calculated using the PAR, PCE, and FRS. Discrimination, calibration, and clinical usefulness of the three equations in predicting the 5-year ASCVD risk were assessed before and after recalibration.

Results

Of 3347 included subjects, 1839 were female. We observed 286 ASCVD events in within 5-year follow-up. All three risk equations had moderate discrimination in both men and women. C-indices of PAR, PCE, and FRS were 0.727 (95% CI, 0.725–0.729), 0.727 (95% CI, 0.725–0.729), and 0.740 (95% CI, 0.738–0.742), respectively, in men; the corresponding C-indices were 0.738 (95% CI, 0.737–0.739), 0.731 (95% CI, 0.730–0.732), and 0.761 (95% CI, 0.760–0.762), respectively, in women. PCE, PAR and FRS substantially underestimated the 5-year ASCVD risk in women by 70, 23 and 51%, respectively. However, PAR and FRS fairly predicted the risk in men and PAR was well calibrated. The calibrations of the three risk equations could be changed by recalibration. The decision curve analyses demonstrated that at the threshold risk of 5%, PCE was the most clinically useful in both men and women after recalibration.

Conclusions

All three risk equations underestimated the 5-year ASCVD risk in women, while PAR and FRS fairly predicted that in men. However, the results of predictive performances for three risk equations are inconsistent, more accurate risk equations are required in the primary prevention of ASCVD aiming to this Uyghur and Kazakh populations.

Keywords: Atherosclerotic, Cardiovascular diseases, Primary prevention, Risk equations, External validation

Background

Atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD), including ischemic heart disease and ischemic stroke, is the leading cause of mortality and disease burden in the world and has been an important public health concern globally [1]. ASCVD incidence risk is associated with factors such as smoking or blood cholesterol, which are potentially modifiable by lifestyle changes or medication use [2]. Timely identification of individuals at high risk of having ASCVD events through risk assessment tools can effectively promote the primary prevention of ASCVD.

The recently released Guideline on the Assessment and Management of Cardiovascular Risk in China [3] recommended calculating ASCVD risks to identify those who at high risk of ASCVD using the newly developed Prediction for ASCVD Risk in China (PAR) risk equation [4], which were generated in general Chinese population. After the development of the PAR, it has been undergone an external validation in a rural northern Chinese population, however, the performance of the PAR in predicting 5-year ASCVD risk was just moderate [5].

The Xinjiang province is a typically multi-ethnic area, which is situated in the northwest of China approximately 2000 miles from Beijing. The Uyghur and Kazakh ethnic groups account for 45.84, 6.50% of the total population in Xinjiang respectively, and they have similar genetic backgrounds to Caucasians. The incidence rate of ASCVD is high among Uyghurs and Kazakhs due to their unique lifestyle, dietary habits, and genetic characteristics. Therefore, it is crucial to identify high-risk individuals using ASCVD risk assessment tools in the prevention of ASCVD. However, there has not been an ASCVD risk prediction model specially targeted at this population.

External validation is a crucial step to determine if a developed risk score can be used to guide the prevention and clinical decision making of ASCVD before applying to a population not used in the risk score’s derivation [6]. The newly developed the China-Population Attributable Risk equations (PAR) has not been validated in this population and whether this equation can be used to guide ASCVD prevention remains unclear.

Consequently, we designed this study to validate the PAR and compare its performance in predicting individual 5-year ASCVD risks against the Pooled Cohort equations (PCE) for White [7] recommended by The American College of Cardiology (ACC) and American Heart Association (AHA) guideline and the Framingham CV risk equation (FRS) [8] using the data from this independent and external Uyghur and Kazakh population in Xinjiang, China.

Methods

Study population

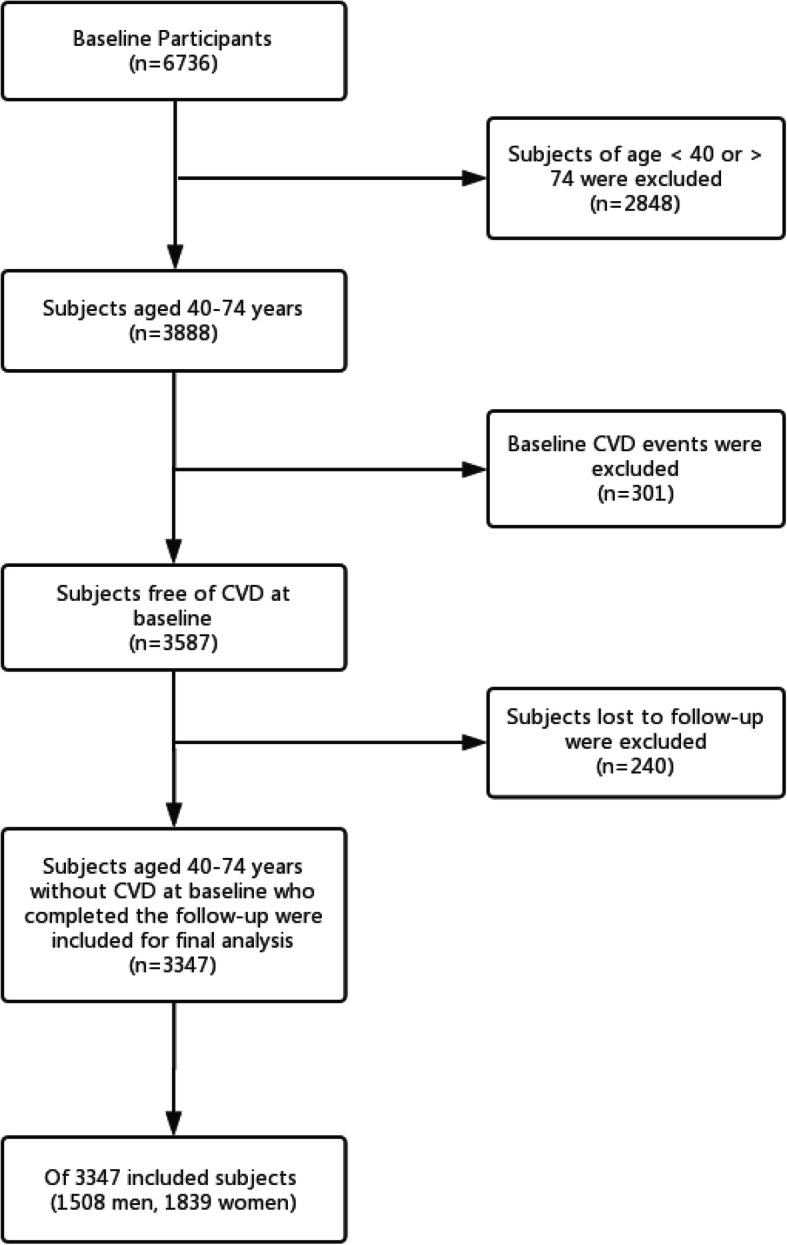

The prospective cohort used in this study was designed to analyze metabolic syndrome and factors that predict the risk of CVD in a multi-ethnic rural area in China. Multistage (prefecture-county-township-village) stratified cluster random sampling was employed to choose participants. Firstly, we chose two representative prefectures (Kashi, Yili) based on the population, ethnicity, geography, economic and cultural development level, respectively in Xinjiang. Second, we randomly selected one county in each prefecture and one township from each county. Finally, a stratified sampling method was used to select the corresponding villages in each township [9]. A total of 6736 adults aged ≥18 years from Xinyuan and Jiashi County in China who had resided in the village for at least 6 months were enrolled in this study between April 2010 and December 2012 and followed for > 5 years on average by the end of December 2017. We restricted the analysis to participants aged 40–74 years without a history of cardiovascular disease (CVD) at baseline to directly compare the three risk assessment tools in predicting the 5-year atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) risk. Based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria of the present study (Fig. 1), 3347 subjects aged 40–74 years were included in the final analyses.

Fig. 1.

Flow diagram of subjects included in this study. CVD, Cardiovascular Disease; ASCVD, Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Disease

Assessment of risk factors

Participants who provided informed consent underwent a face-to-face interview using a standard questionnaire to collect information on sociodemographic characteristics, medical history, and lifestyle habits during field investigation. Current cigarette smoking status was self-reported by participants. Family history of ASCVD was defined as myocardial infarction (MI) or stroke history in at least a parent or sibling. Treated hypertension was defined as hypertension with regular use of antihypertensive medications in the 2-week period before the interview. All participants lived in rural areas of Xinjiang, Northwestern China.

Following the interview, the participants were examined, and anthropometric measurements were obtained by trained health professionals. Waist circumference was defined as the midpoint between the lower rib and upper margin of the iliac crest at minimal respiration, as measured by a nonelastic ruler tape with an insertion buckle at one end to the nearest 0.1 cm. Blood pressure was measured in triplicate after a 5-min seated rest using an electronic sphygmomanometer, and the average of the measurements was obtained as the blood pressure of the individual. A 5-mL fasting blood sample was collected from each subject. The serum glucose, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, and triglycerides were examined by a modified hexokinase enzymatic method using an Olympus AV2700 Biochemical Automatic Analyzer (Olympus, Japan) in the Biochemistry Laboratory of the First Affiliated Hospital of Shihezi University School of Medicine. Diabetes was defined as a fasting glucose level of ≥126 mg/dL in participants or self-report of a previous diagnosis of diabetes with current use of insulin or oral hypoglycemic medications.

Assessment of outcome

An incident ASCVD event, the primary endpoint of this study, was defined as the first diagnosis of nonfatal acute MI or coronary heart disease (CHD) death or fatal or nonfatal stroke. Acute MI was defined as an increase in biochemical markers of myocardial necrosis, accompanied by ischemic symptoms, pathological Q waves, ST-segment elevation or depression, or coronary intervention [10]. CHD death included all fatal events due to MI or other coronary deaths. Stroke was classified as an ischemic or hemorrhagic attack. If the same type of ASCVD event occurred more than once, the first occurrence was considered the end event. The events in the study cohort during follow-up were identified from health insurance claims, patients’ hospital medical records, death registries from the morbidity and mortality surveillance system, and questionnaire responses. We conducted three follow-ups in 2013, 2016 and 2017, respectively. The questionnaire responses were acquired by professional investigators during a face-to-face visit. We usually follow up the subjects in November. First of all, we would record the basic demographic information and follow-up time in the questionnaire. If the subject died during the follow-up period, their family members were asked about the time of death, the place of death and the cause of death, and then the information was checked with the information obtained from the cause of death monitoring system. If the subjects survived, they would be asked whether they were hospitalized, and the reasons and time of hospitalization, and then the information would be verified with medical insurance data and medical record information to record their hospitalization diagnosis.

Statistical analyses

Data were analyzed using SPSS version 17.0 for Windows (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) and R software (version 3.2.3; https://www.r-project.org/). Continuous variables were summarized as sex-specific mean (Standard Deviation, SD) and analyzed using the t-test. Categorical variables were presented as numbers or percentages and analyzed using the chi-square test. Because this study is ongoing and has not yet completed the 10-year follow-up, we can only calculate observed and predicted ASCVD risks at 5 years. The 5-year baseline survival for PAR were calculated based on the reported 5-year Kaplan-Meier ASCVD incidence rate from derivation cohorts (S0(t) = exp. (− 5-year Kaplan-Meier ASCVD incidence rate)) [4, 11]. There was no reported 5-year Kaplan-Meier CVD incidence rate for the FRS, so the baseline survival was estimated as S0(t) = exp. (− 10-year Kaplan-Meier CVD incidence rate/2). The five-year survival rate of PCE was obtained from supplementary materials of Muntner, et al. [11]. Details in Additional file 1: Table S1.

For direct comparison, we used ASCVD as the outcome for all three risk equations. The predicted 5-year ASCVD risk for every participant in this cohort was calculated with the China-Population Attributable Risk equations (PAR) [4] and pooled cohort equations for White (PCE) [7] for ASCVD and the Framingham risk scores for CVD [8]. Details of the three risk equations are presented in Additional file 1: Table S2. The observed 5-year ASCVD risks were calculated using the Kaplan-Meier estimate [12].

Predictive performances of the three risk equations in predicting ASCVD endpoints for this population were evaluated by examining measures of calibration, discrimination, and clinical utility separately in men and women.

Discrimination is the ability of a risk equation to distinguish between individuals who have an ASCVD event during the follow-up and those who do not. Discrimination of each ASCVD risk equation was assessed using the C-index for survival data [13]. We also calculated the D statistic [14] and R2 statistic [15], which is explained variation measures. High R2 values indicate better discrimination.

Calibration refers to how accurately the predicted 5-year risk of ASCVD agrees with the observed 5-year risk. Calibration was assessed graphically by plotting the predicted 5-year risk against the observed risk of incident ASCVD events before and after recalibration, grouped according to deciles of predicted probabilities. A Greenwood-Nam-D’Agostino (GND) chi-square statistic (χ2) suitable for survival data was calculated [16], and a P-value > 0.05 indicates good calibration. Moreover, we also calculated the integrated Brier score for survival data, which measures the predictive accuracy of each ASCVD risk equation, and a lower score represents higher accuracy [17].

Because the characteristics of participants and the prevalence of ASCVD in our cohort were different from those in the derivation cohorts of PCE and PAR, recalibration of the risk equations was necessary before its application to this external population. After the initial evaluation of predictive performance, PCE and PAR were recalibrated by replacement with the mean values of the risk factors and average incidence rates at baseline in our cohort [18]. This process did not change the coefficients for risk factors. FRS has a broader definition of endpoints, so we did not recalibrated FRS.

To compare the clinical utilities of the PCE and PAR, we conducted decision curve analysis (DCA) after recalibration and calculated the net benefit of each equation in predicting the 5-year ASCVD risk [19].

To directly compare the recalibrated PCE and PAR, we calculated the integrated discrimination improvement (IDI), continuous net reclassification improvement (cNRI) and categorical net reclassification improvement (NRI) [20]. The recommended clinically useful cutoff points at 10 years were 5 and 10%, so in the reclassification tables, threshold probabilities of 2.5 and 5% were used for comparison of three risk equations in predicting 5-year ASCVD risk [21]. The study was conducted according to the Transparent Reporting of a multivariable prediction model for Individual Prognosis Or Diagnosis guidelines (TRIPOD) [22], and all analyses were performed separately in men and women.

Results

Baseline characteristics

Following the flowchart (Fig. 1), 3347 subjects aged 40–74 years were included in the final analysis and followed for a median of 7.05 years (IQR, 5.68–7.08). Of these subjects, 1839 (54.94%) were female. The mean ages were 52.10 (SD, 8.92) years and 53.83 (SD, 9.40) years in women and men, respectively. As expected, women had lower blood pressure, a lower prevalence of diabetes, and smoked less frequently. Additional clinical characteristics are shown in Table 1. During the follow-up, 286 subjects (137 men and 149 women) were diagnosed with ASCVD, and the 5-year observed risk of ASCVD was 9.1% (95% CI, 7.8–10.7%) in men and 8.4% (95% CI, 7.2–9.4%) in women.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of study subjects in this validation set

| Characteristics | Women (n = 1839) | Men (n = 1508) |

|---|---|---|

| Age, mean (SD), y | 52.10 (8.92) | 53.83 (9.40) |

| Waist circumference, mean (SD), cm | 84.26 (10.70) | 86.95 (10.15) |

| SBP, mean (SD), mmHg | 131.29 (23.06) | 134.34 (22.57) |

| DBP, mean (SD), mmHg | 82.05 (14.43) | 84.36 (14.18) |

| Total cholesterol, mean (SD), mg/dL | 184.92 (33.47) | 183.40 (33.26) |

| HDL-C, mean (SD), mg/dL | 50.94 (11.80) | 49.11 (9.84) |

| Family history of ASCVD, No. (%) | 67 (3.64) | 48 (3.18) |

| Diabetes, No. (%) | 122 (6.63) | 143 (9.48) |

| Anti-hypertension medications use, No. (%) | 256 (13.92) | 50 (3.32) |

| Current smoker, No. (%) | 238 (12.94) | 632 (41.91) |

| Total person years | 10,800.41 | 9231.16 |

| 5-year Kaplan-Meier ASCVD rate (%) | 8.4 | 9.1 |

| Incidence of ASCVD events within 5 years | 149 | 137 |

Abbreviations: SD Standard Deviation, SBP Systolic blood pressure, DBP Diastolic blood pressure, HDL-C High density lipoprotein cholesterol, ASCVD Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Disease

Discrimination and calibration

The predicted 5-year risks were calculated using published equations for these three models. The distributions of the predicted risks varied considerably between the three models in men and women as shown in Additional file 2: Fig. S1. The average estimated risks with the PCE, PAR, and FRS were 2.5, 6.4, and 4.1%, respectively, in women and 4.7, 9.6, and 9.7%, respectively, in men (Table 2).

Table 2.

Discrimination and calibration statistics for predicted 5-year risk of ASCVD by PCE, PAR and FRS

| PCE | PAR | FRS | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Women | |||

| C statistics (95%CI) | 0.738 (0.703, 0.773) | 0.731 (0.696, 0.766) | 0.761 (0.728, 0.794) |

| D statistics | 1.259 (1.253,1.265) | 1.260 (1.254,1.266) | 1.427 (1.421,1.433) |

| R2 statistics (%) | 27.46 (27.27, 27.65) | 27.50 (27.31, 27.69) | 32.72 (32.54, 32.91) |

| Brier Score a | 0.0491 | 0.0486 | 0.0487 |

| Greenwood-Nam-D’agostino (GND) calibration χ2 c | 86.26 | 13.50 | 48.13 |

| P value for GND test | 0.000 | 0.009 | 0.000 |

| Observed events b | 153.94 | 153.94 | 153.94 |

| Predicted events | 46.11 | 118.09 | 74.86 |

| P/O | 0.30 | 0.77 | 0.49 |

| Average predicted risk (%) | 2.5 | 6.4 | 4.1 |

| Average observed risk (%) | 8.4 | 8.4 | 8.4 |

| Proportion of predicted risk> 5% (%) | 16.51 | 54.05 | 29.31 |

| Men | |||

| C statistics (95%CI) | 0.727 (0.689, 0.766) | 0.727 (0.684, 0.770) | 0.740 (0.703, 0.777) |

| D statistics | 1.293 (1.286,1.300) | 1.301 (1.294,1.308) | 1.355 (1.348,1.362) |

| R2 statistics (%) | 28.54 (28.32,28.76) | 28.79 (28.57,29.01) | 30.48 (30.26,30.70) |

| Brier Score a | 0.0525 | 0.0523 | 0.0529 |

| Greenwood-Nam-D’agostino (GND) calibration χ2 d | 39.86 | 4.11 | 13.58 |

| P value for GND test | 0.000 | 0.534 | 0.019 |

| Observed events b | 137.9 | 137.9 | 137.9 |

| Predicted events | 70.87 | 144.72 | 145.8 |

| P/O | 0.51 | 1.05 | 1.06 |

| Average predicted risk (%) | 4.7 | 9.6 | 9.7 |

| Average observed risk (%) | 9.1 | 9.1 | 9.1 |

| Proportion of predicted risk> 5% (%) | 55.74 | 49.92 | 57.31 |

Abbreviations: P Predicted events, O Observed events, PCE Pooled Cohort Risk Equations, PAR China-PAR risk equation, FRS Framingham Risk Score 2008

aLower score indicates better accuracy of risk estimates;

bAdjusted using Kaplan-Meier method;

cDeciles were set as 5 to ensure that each decile contained at least 5 events

dDeciles were set as 6 to ensure that each decile contained at least 5 events

The discrimination and calibration performance metrics for PCE, PAR, and FRS are presented in Table 2. The C-indices of PAR, PCE, and FRS were 0.727 (95% CI, 0.689, 0.766), 0.727 (95% CI, 0.684, 0.770), and 0.740 (95% CI, 0.703, 0.777), respectively, in men; the corresponding C indices were 0.731 (95% CI, 0.703, 0.773), 0.738 (95% CI, 0.696, 0.766), and 0.761 (95% CI, 0.728, 0.794), respectively, in women. In women, the D discrimination statistic (a higher score indicates better discrimination) for FRS was higher than that for PCE and PAR, while the D discrimination statistic for FRS was higher than that for PCE and PAR in men. The RD2 proposed by Royston and Sauerbrei [15] as an explained variation measure for FRS in women was 5% higher than those for PCE and PAR, whereas the RD2 for PCE in men was similar to that of PAR and lower than that of FRS. We used the integrated Brier score to compare the prediction accuracy of risk equations, and a lower Brier score indicated greater accuracy of a risk equation. The Brier score for PCE was 0.0491 and was higher than that for PAR (0.0486) and FRS (0.0487) in women. The PAR had the lowest Brier score (0.0523), compared with PCE (0.0525) and FRS (0.0529) in men.

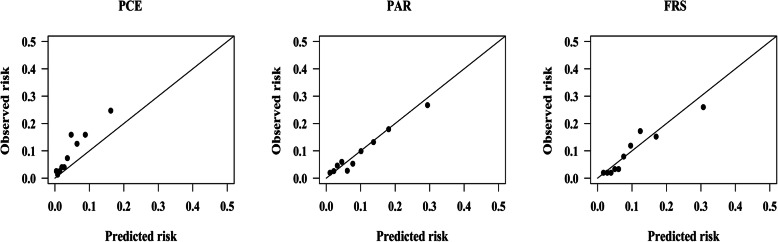

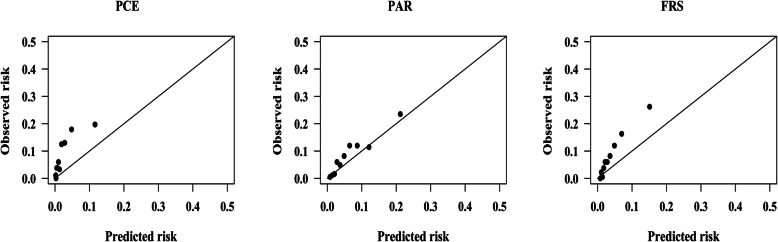

The observed ASCVD events (adjusted using Kaplan-Meier method) was 137.90, while the predicted ASCVD events for PCE, PAR, and FRS was 70.87, 144.72, and 145.80, respectively, in men, giving a Predicted events/Observed events (P/O) of 0.51, 1.05, and 1.06, as shown in Table 2. The calibration plots (Fig. 2) show that FRS and PAR slightly overestimated the ASCVD risk, while PCE systematically underestimated the 5-year ASCVD risk in men by nearly 50%. The PCE, PAR and FRS substantially underestimated ASCVD risk by approximately 70, 23 and 51%, respectively, in women. The PAR was well calibrated (GND test χ2 = 4.11, P = 0.534). Calibration plots of PCE, PAR, and FRS in women are shown in Fig. 3.

Fig. 2.

Calibration plots for the PCE, PAR and FRS in men before recalibration. PCE, Pooled Cohort Risk Equations; PAR, China-PAR risk equation; FRS, Framingham Risk Score 2008. GND test chi-square statistics for risk equations: PCE: 39.86; P < 0.001. PAR: 4.11; P = 0.534. FRS: 13.58; P = 0.019

Fig. 3.

Calibration plots for the PCE, PAR and FRS in women before recalibration. PCE, Pooled Cohort Risk Equations; PAR, China-PAR risk equation; FRS, Framingham Risk Score 2008. GND test chi-square statistics for risk equations: PCE: 86.26; P < 0.001. PAR: 13.50; P = 0.009. FRS: 48.13; P < 0.001

Recalibration of risk equations

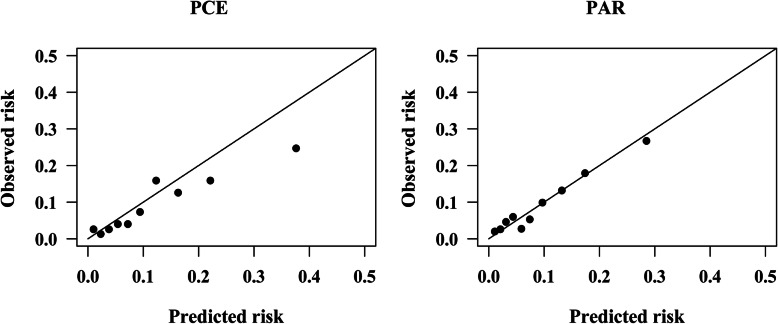

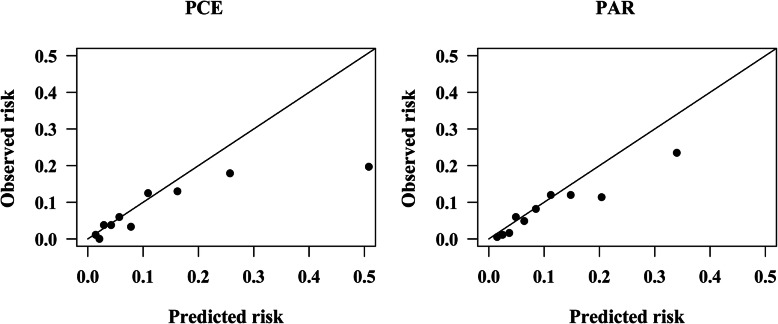

Recalibration did not change discriminations of risk equations, and calibrations of PCE and PAR in predicting the 5-year ASCVD risk slightly improved after recalibration in men, as shown in Fig. 4 and Fig. 5. After recalibration, the GND test χ2 for PAR was 3.47 (P = 0.628). The calibration of PCE in women improved but was still poor. Calibration plots in Fig. 5 showed that the overestimation of PCE and PAR in women mainly occurred in the top two deciles after recalibration, in which subjects had a 5-year estimated risk of ≥5%.

Fig. 4.

Calibration plots for the PCE and PAR in men after recalibration. PCE, Pooled Cohort Risk Equations; PAR, China-PAR risk equation; GND test chi-square statistics for risk equations: PCE: 26.74; P < 0.001. PAR: 3.47; P = 0.628

Fig. 5.

Calibration plots for the PCE and PAR in women after recalibration. PCE, Pooled Cohort Risk Equations; PAR, China-PAR risk equation; GND test chi-square statistics for risk equations: PCE: 92.83; P < 0.001. PAR: 26.17; P < 0.001

Risk reclassification

Reclassification tables were constructed using clinically useful cutoff points of 2.5 and 5%. These tables show the numbers of women and men in our cohort who would be reclassified into the different risk groups while using different risk equations. For example, as shown in Table 3, with PCE, 53 (14.52%) of 365 women with a PAR risk of 2.5–5% would be reclassified as having ≥5% risk and 128 (35.07%) would be reclassified as having < 2.5% risk among women without ASCVD events. Of 255 women with PAR risk of < 2.5%, 28 (10.98%) were incorrectly reclassified into higher risk categories, and 127 (13.35%) of 951 women with FRS risk of ≥5% were correctly reclassified into lower categories among women without ASCVD events, resulting in a negative nonevent NRI of − 0.108 (− 0.131, − 0.088). In women with ASCVD events, 3 subject was correctly upgraded to higher-risk groups and 8 of them were incorrectly downgraded to lower-risk groups, leading to an event NRI of 0.033 (− 0.008, 0.080); thus, the total NRI was − 0.075(− 0.123, − 0.025), which indicated that using PCE, 7.5% of subjects would be correctly reclassified compared with PAR. Compared with the PAR, the PCE showed improved reclassification based on the NRI and cNRI in women. IDI showed no difference between PCE and PAR (− 0.005, 95% CI: − 0.018-0.013).

Table 3.

Reclassification table comparing the recalibrated-PCE to the recalibrated-PAR to predict 5-year risk of ASCVD

| PCE | PAR | Column total | N(%) of reclassified | NRI | cNRI | IDI | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low | Moderate | High | ||||||

| Women | ||||||||

| Nonevent (n = 1571) | −0.108 (−0.131, − 0.088) | −0.071 (− 0.119, − 0.023) | 0.001(− 0.011, 0.008) | |||||

| Low | 227 | 128 | 8 | 363 | 136 (37.47) | |||

| Moderate | 23 | 184 | 119 | 326 | 142 (43.56) | |||

| High | 5 | 53 | 824 | 882 | 58 (6.58) | |||

| Row total | 255 | 365 | 951 | 1571 | 336 (21.39) | |||

| Event (n = 149) | 0.033 (−0.008, 0.080) | −0.339 (−0.495, −0.191) | −0.004 (− 0.010, 0.001) | |||||

| Low | 2 | 1 | 0 | 3 | 1 (33.33) | |||

| Moderate | 0 | 7 | 7 | 14 | 7 (50.00) | |||

| High | 0 | 3 | 129 | 132 | 3 (2.27) | |||

| Row total | 2 | 11 | 136 | 149 | 11 (7.38) | |||

| Total | −0.075(−0.123, −0.025) | −0.409 (−0.584, −0.256) | − 0.005 (− 0.018, 0.013) | |||||

| Men | ||||||||

| Nonevent (n = 1339) | 0.093 (0.070,0.117) | 0.448 (0.399, 0.497) | −0.001 (−0.013, 0.019) | |||||

| Low | 205 | 34 | 2 | 241 | 36 (14.94) | |||

| Moderate | 62 | 128 | 37 | 227 | 99 (43.61) | |||

| High | 13 | 120 | 738 | 871 | 133 (15.27) | |||

| Row total | 280 | 282 | 777 | 1339 | 268 (20.01) | |||

| Event (n = 137) | −0.069(−0.125,-0.019) | −0.441(−0.578, −0.300) | 0.023 (−0.005, 0.031) | |||||

| Low | 4 | 1 | 1 | 6 | 2 (33.33) | |||

| Moderate | 2 | 2 | 1 | 5 | 3 (60.00) | |||

| High | 0 | 13 | 113 | 126 | 13 (10.32) | |||

| Row total | 6 | 16 | 115 | 137 | 18 (13.14) | |||

| Total | 0.025 (−0.036,0.077) | 0.006(−0.147, 0.166) | 0.024 (0.001, 0.051) | |||||

Abbreviations: PCE Pooled Cohort Risk Equations, PAR China-PAR risk equation

NRI: net reclassification improvement; cNRI: continuous net reclassification improvement; IDI: integrated discrimination improvement

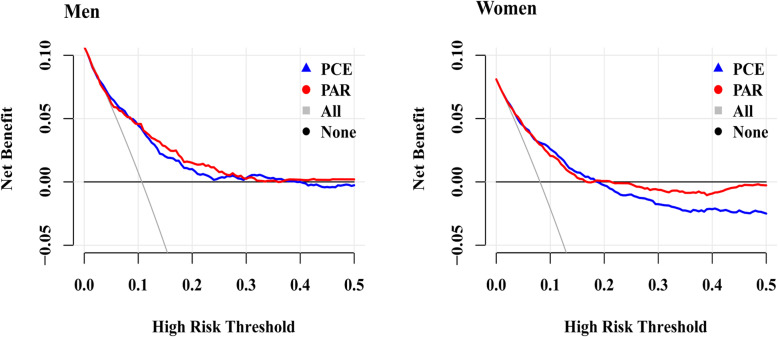

Decision curve analysis (DCA)

We conducted DCA to compare the clinical usefulness of the three risk equations in predicting the 5-year ASCVD risks after recalibration, as shown in Fig. 6 and Additional file 1: Table S3. At the threshold risk of 5% among men, the net benefits for the PCE and PAR were 0.014, 0.010 greater than the values obtained by assuming positive in all subjects. This indicated that 27, 19 additional true-positive ASCVD events per 100 subjects can be correctly predicted without an increase in the number of false-positive results using the PCE and PAR, respectively. Similarly, in women, the net benefits were 0.043 and 0.042 for the PCE and PAR, respectively. The net benefits of PCE, PAR and FRS before recalibration were presented in Additional file 1: Table S4.

Fig. 6.

Decision curves for the PCE and PAR after recalibration. PCE, Pooled Cohort Risk Equations; PAR, China-PAR risk equation

Discussion

We conducted this study to externally validate the PAR equations newly recommended by the guideline and compared the performance of PAR against FRS and PCE in predicting the 5-year ASCVD risk both directly and after recalibration. The discrimination abilities in predicting the 5-year ASCVD risk for all three risk equations were moderate in both men and women of this cohort. All three risk equations systematically underestimated the 5-year ASCVD risk across nearly all ten deciles and were poorly calibrated for the outcome of ASCVD in women. The PAR had a relatively better calibration than the PCE and FRS, with 23% underestimation in women. The PAR and FRS fairly predicted the risk in men with a P/O of 1.05 and 1.06, respectively, whereas the PCE underestimated it by nearly 50% and was poorly calibrated. The results from comparisons of three risk equations based on the NRI, cNRI, and NRI statistics were not exactly consistent with those results measured by C-indices. For example, the FRS (0.761) had a higher C index than PCE (0.738) in women, however, the results based on NRI, cNRI and IDI suggested that PCE had a better reclassification ability than FRS. A study [23] suggested that the NRI and IDI could be strongly affected by miscalibration of a model, and the PCE and PAR in women and the PCE in men were still poorly calibrated after recalibration; thus, the results may be affected.

The PCE, released by the American College of Cardiology and the American Heart Association in 2013, has undergone numerous external validations in various populations and settings. Most results from external validation studies indicated that the PCE tended to overestimate ASCVD risk [11, 24–27]. For example, Muntner et al. [11] found that the PCE overestimated the 5-year ASCVD risk in the overall population and demonstrated that the overestimation may be explained by the lack of active ASCVD surveillance and the high prevalence of statin use in contemporary cohorts. A study conducted in a large contemporary, multiethnic population suggested that the PCE substantially overestimated the observed 5-year risk and was poorly calibrated [24]. Similar results from the PREDICT study in New Zealand showed that the PCE systematically overestimated the ASCVD risk by approximately 40% in men and 60% in women [25].

Because the Asian population was excluded in the PCE’s derivation cohorts, there is substantial overestimation when PCE was externally validated in the Asian population [28–30]. The PCE had moderate discrimination and overestimated the 10-year ASCVD risk in the Malaysian population. The researchers suggested that the overestimation could be explained by the treatment during the 10-year follow-up and observed that the proportion of patients receiving statin therapy increased from 9.7 to 63.7% in the 10-year period [28]. The Hong Kong Cardiovascular Risk Factor Prevalence Study [30] also found that the PCE was poorly calibrated for men and had moderate discrimination in both men and women.

Most importantly, the possible reasons for the overestimation of PCE may be the under-ascertainment of ASCVD events, increase in statin use, decline in ASCVD incidence rates over time, and different ethnic backgrounds [11, 26, 28].

However, the PCE systematically underestimated risks both in men and women in this population, similar to the results from several studies [5, 31–33]. The Korean Heart Study reported that the PCE (White model) overestimated the 10-year ASCVD risk by 56.5% in men but underestimated it by 27.9% in women. They suggested that the varying rates of ASCVD incidence and associated risk factors from the derivation cohorts of PCE may be the reason that the PCE did not calibrate well in their study [29]. The results from the Austrian health-screening program demonstrated that the PCE underestimated 5-year ASCVD risk over the whole range of predicted risks and P/O ratios were 0.54 for women and 0.73 for men [31]. The PCE systematically underpredicted the 5-year ASCVD risks in subjects from disadvantaged communities in Cleveland, and researchers concluded that the poor calibration of the PCE in disadvantaged communities could be explained by the variations in ASCVD risk factors and environmental and other neighborhood-level exposures across the socioeconomic spectrum [32]. Similar results from the REGARDS study revealed that the PCE underestimated ASCVD risk in subjects with more social deprivation but overestimated ASCVD risk in subjects with less social deprivation [33]. Subjects in this external validation population were from disadvantaged rural areas in northwestern China and more deprived than individuals from other areas in China.

The PAR, derived from the general Chinese population, had moderate discrimination and was well calibrated in men but substantially underestimated the 5-year ASCVD risk in women in this study. However, a recently published study conducted in a rural northern Chinese population indicated that the PAR fairly predicted the 5-year ASCVD risk in men but overestimated it by 29.4% in women [5].

Although FRS was designed to predict a broader endpoint of global CVD, it underpredicted the 5-year risk in women. Nevertheless, the FRS slightly overestimated the risk in men with a P/O of 1.06 and was better calibrated.

Underestimation of the 5-year ASCVD risk in women by three risk equations could be explained by several aspects. Xinjiang is on the “stroke belt,” and the estimated age-standardized incidence of stroke in Xinjiang per 100,000 persons is 191 [34], higher than that in the United States (140 per 100,000) [35]. The incidence of ASCVD is close between men and women in this population. Thus, the higher incidence rates of ASCVD in China than that in the USA may be the reason why the PCE and FRS, derived from the US population, underestimated the ASCVD risk in women. Researchers have shown that social deprivation is associated with high ASCVD incidence rates [36, 37]. Most Kazakh and Uygur individuals live in a typical low-income and multi-ethnic rural area in northwest China, Xinjiang, where most live on $1.00 or less. The prevalence rate of dyslipidemia and hypertension in this population is relatively higher than that in the Han nationality with low awareness, treatment, and control rates due to their genetic backgrounds and unique dietary habits [38, 39], so the ASCVD incidence rates in this population are relatively high [40]. This may partly explain why the PAR, developed in the general Chinese population, underestimated the 5-year ASCVD risk of women in this population. Another potential reason for ASCVD risk underestimation by three risk equations is that the cohort in this study is more contemporary than the derivation cohorts of these two risk equations, and the quantitative relationship between risk factors and ASCVD events may have changed with time. The study population had a much lower level of TC and a high level of HDL than that in the derivation population of three risk equations, so risks predicted by using the coefficients from three risk equations might be lower. These factors might explain, to some extent, the findings of risk underestimation by the PCE and PAR in women.

Recalibration is necessary before applying a risk equation to a specific population which is excluded in the risk equation’s derivation cohorts and allows us to directly compare three risk equations using reclassification tables. Therefore, we recalibrated the PCE and PAR to our cohorts using the method proposed by D’Agostino et al. [18]. However, there was an overestimation of ASCVD risk after recalibration, especially in women, which may be explained by that recalibration would not change the coefficients between risk factors and ASCVD outcome, but risk factors in this population were also different from those cohorts and the incidence rate of ASCVD in this population was higher than that in the derivation cohort of three risk equations. More details can be seen in Additional file 1: Table S5. Improved calibration is of vital importance to risk classification and evaluation of net benefit, so recalibration can be a useful method to tailor and generalize a risk equation to an external population [41].

DCA was performed to investigate the clinical usefulness of the three equations. At the recommended threshold risk of 5% for the 5-year ASCVD risk, the most useful risk equation was the PCE for both men and women at the threshold probability of 5% after recalibration. A higher risk threshold will leave more high-risk subjects untreated, and a lower threshold will lead to more unnecessary treatments. Thus, it is important to set an accurate and appropriate threshold to identify high-risk subjects to balance the benefits and risks of recommended therapies and guide decision making in practice.

Strengths and limitations

One strength of our study is the complete ascertainment of ASCVD events using health insurance claims, patients’ hospital medical records, and questionnaire responses; this may partly explain the risk underestimation by the PCE and PAR in women. Moreover, this population is representative, and the results can be generalized to the entire Kazakh and Uygur populations.

Nevertheless, some limitations merit explanations. The main limitation is that the sample size of our study is relatively small. Another limitation is that this study is ongoing and the follow-up period is < 10 years, so we can only calculate the 5-year ASCVD risk. The baseline survival of FRS was calculated based on 10-year Kaplan-Meier CVD rate, which was different from PCE and PAR. This may cause miscalibration of three equations, which were designed to predict 10-year ASCVD risk. A future study is needed to ensure their accurate calibrations over a longer period.

Conclusions

Therefore, we have externally validated three risk equations in predicting the 5-year ASCVD risk in an underrepresented population from rural areas in northwestern China. Results indicated that all three risk equations have moderate discrimination in both men and women. However, they underestimated the ASCVD risk for women. The PAR, derived from Chinese cohorts, had moderate discrimination and was well calibrated in men but underestimated the risk in women. After recalibration, the PAR had the most accurate predictions. The PCE had better reclassification than PAR. DCA indicated that, at the threshold risk of 5%, the most clinically useful risk equation was PCE in both men and women after recalibration. Indicators used to examine predictive performances of three risk equations showed inconsistent results, none of them is suitable for direct application in this population, even after recalibration. Future ASCVD risk equations special for this Kazakh and Uygur population are required in the health screening program for the primary prevention of ASCVD.

Supplementary information

Additional file 1 Table S1. Parameters of three risk equations used in this study for men and women. Table S2. Summary of risk factors and outcome of three risk equations used in this external validation study. Table S3. Net benefit analysis for preventing ASCVD at different thresholds of Pt after recalibration. Table S4. Net benefit analysis for preventing ASCVD at different thresholds of Pt before recalibration. Table S5. Comparisons of baseline characteristics between three risk equations and the study population.

Additional file 2 Fig. S1. Distribution of risk estimated from the PCE, PAR, and FRS among men and women.

Acknowledgments

We sincerely thank those who participated in the study. We would also like to acknowledge the clinical laboratory of First Affiliated Hospital of Shihezi University School of Medicine for their work.

Abbreviations

- ACC

American College of Cardiology

- AHA

American Heart Association

- ASCVD

Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Disease

- CHD

Coronary Heart Disease

- CVD

Cardiovascular Disease

- cNRI

continuous Net Reclassification Improvement

- DBP

Diastolic Blood Pressure

- DCA

Decision Curve Analysis

- FRS

Framingham Risk Score

- GND

Greenwood-Nam-D’Agostino

- HDL-C

High Density Lipoprotein Cholesterol

- IDI

Integrated Discrimination Improvement

- PAR

China-Population Attributable Risk equations

- PCE

Pooled Cohort Equations

- SBP

Systolic Blood Pressure

- SD

Standard Deviation

- NRI

Net Reclassification Improvement

Authors’ contributions

(I) Conception and design: SXG and YXJ; (II) Administrative support: None; (III) Provision of study materials or patients: SXG; (IV) Collection and assembly of data: All authors; (V) Data analysis and interpretation: YXJ, RLM, and JH; (VI) Manuscript writing: All authors; (VII) Final approval of manuscript: All authors.

Authors’ information

Yunxing Jiang and Rulin Ma contributed equally to this work.

Funding

This study was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 81560551) and the Shihezi University Innovation Outstanding Young Talents Program (Natural Science) (No. CXPY201908).

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request. The Chinese questionnaire copy may be requested from the authors.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the Institutional Ethics Review Board (IERB) of the First Affiliated Hospital of Shihezi University School of Medicine (IERB No. SHZ2010LL01). All of the participants provided their written informed consent prior to the start of the study.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Yunxing Jiang and Rulin Ma contributed equally to this work.

Contributor Information

Jia He, Email: hejia123.shihezi@163.com.

Shuxia Guo, Email: gsxshzu@sina.com.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1186/s12889-020-09579-4.

References

- 1.Zhou M, Wang H, Zhu J, Chen W, Wang L, Liu S, et al. Cause-specific mortality for 240 causes in China during 1990-2013: a systematic subnational analysis for the global burden of disease study 2013. Lancet. 2016;387(10015):251–272. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00551-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.O'Donnell MJ, Chin SL, Rangarajan S, Xavier D, Liu L, Zhang H, et al. Global and regional effects of potentially modifiable risk factors associated with acute stroke in 32 countries (INTERSTROKE): a case-control study. Lancet. 2016;388(10046):761–775. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30506-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.China TJTFfGotAaMoCRi Guideline on the assessment and Management of Cardiovascular Risk in China. Chin J Prev Med. 2019;53(1):13. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.issn.0253-9624.2019.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yang X, Li J, Hu D, Chen J, Li Y, Huang J, et al. Predicting the 10-year risks of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease in Chinese population: the China-PAR project (prediction for ASCVD risk in China) Circulation. 2016;134(19):1430–1440. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.116.022367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tang X, Zhang D, He L, Wu N, Si Y, Cao Y, et al. Performance of atherosclerotic cardiovascular risk prediction models in a rural northern Chinese population: results from the Fangshan cohort study. Am Heart J. 2019;211:34–44. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2019.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hlatky MA, Greenland P, Arnett DK, Ballantyne CM, Criqui MH, Elkind MS, et al. Criteria for evaluation of novel markers of cardiovascular risk: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2009;119(17):2408–2416. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.192278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Goff DC, Jr, Lloyd-Jones DM, Bennett G, Coady S, D'Agostino RB, Gibbons R, et al. 2013 ACC/AHA guideline on the assessment of cardiovascular risk: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association task force on practice guidelines. Circulation. 2014;129(25 Suppl 2):S49–S73. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000437741.48606.98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.D'Agostino RB, Sr, Vasan RS, Pencina MJ, Wolf PA, Cobain M, Massaro JM, et al. General cardiovascular risk profile for use in primary care: the Framingham heart study. Circulation. 2008;117(6):743–753. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.699579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Guo SX, Zhang XH, Zhang JY, He J, Yan YZ, Ma JL, et al. Visceral adiposity and anthropometric indicators as screening tools of metabolic syndrome among low income rural adults in Xinjiang. Sci Rep. 2016;6:36091. doi: 10.1038/srep36091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Alpert JS, Thygesen K, Antman E, Bassand JP. Myocardial infarction redefined--a consensus document of the joint European Society of Cardiology/American College of Cardiology Committee for the redefinition of myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2000;36(3):959–969. doi: 10.1016/S0735-1097(00)00804-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Muntner P, Colantonio LD, Cushman M, Goff DC, Jr, Howard G, Howard VJ, et al. Validation of the atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease pooled cohort risk equations. Jama. 2014;311(14):1406–1415. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.2630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Colette D. Modeling survival data in medical research. London: Chapman & Hall; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Harrell FE, Jr, Lee KL, Mark DB. Multivariable prognostic models: issues in developing models, evaluating assumptions and adequacy, and measuring and reducing errors. Stat Med. 1996;15(4):361–387. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0258(19960229)15:4<361::AID-SIM168>3.0.CO;2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Royston P, Sauerbrei W. A new measure of prognostic separation in survival data. Stat Med. 2004;23(5):723–748. doi: 10.1002/sim.1621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Royston P. Explained variation for survival models. Stata J. 2006;6(1):83–96. doi: 10.1177/1536867X0600600105. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Demler OV, Paynter NP, Cook NR. Tests of calibration and goodness-of-fit in the survival setting. Stat Med. 2015;34(10):1659–1680. doi: 10.1002/sim.6428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Graf E, Schmoor C, Sauerbrei W, Schumacher M. Assessment and comparison of prognostic classification schemes for survival data. Stat Med. 1999;18(17–18):2529–2545. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0258(19990915/30)18:17/18<2529::AID-SIM274>3.0.CO;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Janssen KJ, Vergouwe Y, Kalkman CJ, Grobbee DE, Moons KG. A simple method to adjust clinical prediction models to local circumstances. Can J Anaesth. 2009;56(3):194–201. doi: 10.1007/s12630-009-9041-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vickers AJ, Elkin EB. Decision curve analysis: a novel method for evaluating prediction models. Med Decis Making. 2006;26(6):565–574. doi: 10.1177/0272989X06295361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pencina MJ, D'Agostino RB, Sr, Steyerberg EW. Extensions of net reclassification improvement calculations to measure usefulness of new biomarkers. Stat Med. 2011;30(1):11–21. doi: 10.1002/sim.4085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yang XL, Chen JC, Li JX, Cao J, Lu XF, Liu FC, et al. Risk stratification of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease in Chinese adults. Chronic Dis Transl Med. 2016;2(2):102–109. doi: 10.1016/j.cdtm.2016.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Moons KG, Altman DG, Reitsma JB, Ioannidis JP, Macaskill P, Steyerberg EW, et al. Transparent reporting of a multivariable prediction model for individual prognosis or diagnosis (TRIPOD): explanation and elaboration. Ann Intern Med. 2015;162(1):W1–73. doi: 10.7326/M14-0698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Leening MJ, Vedder MM, Witteman JC, Pencina MJ, Steyerberg EW. Net reclassification improvement: computation, interpretation, and controversies: a literature review and clinician's guide. Ann Intern Med. 2014;160(2):122–131. doi: 10.7326/M13-1522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rana JS, Tabada GH, Solomon MD, Lo JC, Jaffe MG, Sung SH, et al. Accuracy of the atherosclerotic cardiovascular risk equation in a large contemporary, multiethnic population. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016;67(18):2118–2130. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2016.02.055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pylypchuk R, Wells S, Kerr A, Poppe K, Riddell T, Harwood M, et al. Cardiovascular disease risk prediction equations in 400 000 primary care patients in New Zealand: a derivation and validation study. Lancet. 2018;391(10133):1897–1907. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)30664-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.DeFilippis AP, Young R, Carrubba CJ, McEvoy JW, Budoff MJ, Blumenthal RS, et al. An analysis of calibration and discrimination among multiple cardiovascular risk scores in a modern multiethnic cohort. Ann Intern Med. 2015;162(4):266–275. doi: 10.7326/M14-1281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Motamed N, Rabiee B, Perumal D, Poustchi H, Miresmail SJ, Farahani B, et al. Comparison of cardiovascular risk assessment tools and their guidelines in evaluation of 10-year CVD risk and preventive recommendations: a population based study. Int J Cardiol. 2017;228:52–57. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2016.11.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chia YC, Lim HM, Ching SM. Validation of the pooled cohort risk score in an Asian population - a retrospective cohort study. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2014;14:163. doi: 10.1186/1471-2261-14-163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jung KJ, Jang Y, Oh DJ, Oh BH, Lee SH, Park SW, et al. The ACC/AHA 2013 pooled cohort equations compared to a Korean risk prediction model for atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. Atherosclerosis. 2015;242(1):367–375. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2015.07.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lee CH, Woo YC, Lam JK, Fong CH, Cheung BM, Lam KS, et al. Validation of the pooled cohort equations in a long-term cohort study of Hong Kong Chinese. J Clin Lipidol. 2015;9(5):640–646.e642. doi: 10.1016/j.jacl.2015.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wallisch C, Heinze G, Rinner C, Mundigler G, Winkelmayer WC, Dunkler D. External validation of two Framingham cardiovascular risk equations and the pooled cohort equations: a nationwide registry analysis. Int J Cardiol. 2019;283:165–170. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2018.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dalton JE, Perzynski AT, Zidar DA, Rothberg MB, Coulton CJ, Milinovich AT, et al. Accuracy of cardiovascular risk prediction varies by neighborhood socioeconomic position: a retrospective cohort study. Ann Intern Med. 2017;167(7):456–464. doi: 10.7326/M16-2543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Colantonio LD, Richman JS, Carson AP, Lloyd-Jones DM, Howard G, Deng L, et al. Performance of the atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease pooled cohort risk equations by social deprivation status. J Am Heart Assoc. 2017;6(3):e005676. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.117.005676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Xu G, Ma M, Liu X, Hankey GJ. Is there a stroke belt in China and why? Stroke. 2013;44(7):1775–1783. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.113.001238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Feigin VL, Lawes CM, Bennett DA, Barker-Collo SL, Parag V. Worldwide stroke incidence and early case fatality reported in 56 population-based studies: a systematic review. Lancet Neurol. 2009;8(4):355–369. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(09)70025-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Woodward M, Brindle P, Tunstall-Pedoe H. Adding social deprivation and family history to cardiovascular risk assessment: the ASSIGN score from the Scottish heart health extended cohort (SHHEC) Heart. 2007;93(2):172–176. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2006.108167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Diez Roux AV, Merkin SS, Arnett D, Chambless L, Massing M, Nieto FJ, et al. Neighborhood of residence and incidence of coronary heart disease. N Engl J Med. 2001;345(2):99–106. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200107123450205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wang Y, Zhang J, Ding Y, Zhang M, Liu J, Ma J, et al. Prevalence of hypertension among adults in remote rural areas of Xinjiang, China. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2016;13(6):524. doi: 10.3390/ijerph13060524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ma J, Guo S, Ma R, Zhang J, Liu J, Ding Y, et al. An evaluation on the effect of health education and of low-dose statin in dyslipidemia among low-income rural Uyghur adults in far Western China: a comprehensive intervention study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2015;12(9):11410–11421. doi: 10.3390/ijerph120911410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mao L, Zhang X, Hu Y, Wang X, Song Y, He J, et al. Nomogram based on cytokines for cardiovascular diseases in Xinjiang Kazakhs. Mediators Inflamm. 2019;2019:4756295. doi: 10.1155/2019/4756295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Damen JA, Pajouheshnia R, Heus P, Moons KGM, Reitsma JB, Scholten R, et al. Performance of the Framingham risk models and pooled cohort equations for predicting 10-year risk of cardiovascular disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Med. 2019;17(1):109. doi: 10.1186/s12916-019-1340-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1 Table S1. Parameters of three risk equations used in this study for men and women. Table S2. Summary of risk factors and outcome of three risk equations used in this external validation study. Table S3. Net benefit analysis for preventing ASCVD at different thresholds of Pt after recalibration. Table S4. Net benefit analysis for preventing ASCVD at different thresholds of Pt before recalibration. Table S5. Comparisons of baseline characteristics between three risk equations and the study population.

Additional file 2 Fig. S1. Distribution of risk estimated from the PCE, PAR, and FRS among men and women.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request. The Chinese questionnaire copy may be requested from the authors.