Abstract

Indigenous communities in Latin America and elsewhere have complex bodies of knowledge, but Western health services generally approach them as vulnerable people in need of external solutions. Intercultural dialogue recognises the validity and value of Indigenous standpoints, and participatory research promotes reciprocal respect for stakeholder input in knowledge creation.

As part of their decades-long community-based work in Mexico’s Guerrero State, researchers at the Centro de Investigación de Enfermedades Tropicales responded to the request from Indigenous communities to help them address poor maternal health. We present the experience from this participatory research in which both parties contributed to finding solutions for a shared concern. The aim was to open an intercultural dialogue by respecting Indigenous skills and customs, recognising the needs of health service stakeholders for scientific evidence.

Three steps summarise the opening of intercultural dialogue. Trust building and partnership based on mutual respect and principles of cultural safety. This focused on understanding traditional midwifery and the cultural conflicts in healthcare for Indigenous women. A pilot randomised controlled trial was an opportunity to listen and to adjust the lexicon identifying and testing culturally coherent responses for maternal health led by traditional midwives. Codesign, evaluation and discussion happened during a full cluster randomised trial to identify benefits of supporting traditional midwifery on maternal outcomes. A narrative mid-term evaluation and cognitive mapping of traditional knowledge offered additional evidence to discuss with other stakeholders the benefits of intercultural dialogue. These steps are not mechanistic or invariable. Other contexts might require additional steps. In Guerrero, intercultural dialogue included recovering traditional midwifery and producing high-level epidemiological evidence of the value of traditional midwives, allowing service providers to draw on the strengths of different cultures.

Keywords: health systems, maternal health, public health, cluster randomised trial, other study design

Summary box.

Modern economic development has resulted in cultural loss, marginalisation and worst health outcomes, including poorer maternal outcomes, for many Indigenous communities.

Many Indigenous communities in Latin America still have traditional knowledge and potentially effective healthcare practices.

Intercultural dialogue can improve functioning of Western health services for Indigenous communities, respecting cultural differences and leveraging local resources.

This three-step approach strengthened traditional enabling environments for maternal health and contributed to positive outcomes among Indigenous women in Guerrero, Mexico.

Building intercultural relationships takes time. Financial restrictions and changes in the internal dynamics of stakeholders can threaten the process.

Promotion of intercultural dialogue by researchers is not a mechanistic recipe of predetermined steps; it hinges on their commitment and deep respect for communities.

Introduction

Indigenous communities in Latin America and elsewhere developed complex bodies of knowledge, know-how and practices over many generations.1 These include ways, that are anchored in the worldview and territorial context of each culture, to address health needs.2 3 Notwithstanding their diversity, most traditional medicine practitioners use local resources and approach health on multiple levels—physical, emotional, mental, spiritual and environmental—often all at once.4

Colonial history and the establishment of Western culture have increased political and economic marginalisation of Indigenous communities.5 Disrespect of Indigenous cultures, implicit in this marginalisation, promotes a sense of inferiority and ignoring Indigenous knowledge.6 7 Acculturation, territorial loss, decay of healthcare traditions, socioeconomic conditions and conflictive interface with Western health institutions have negative effects on Indigenous health, including high burdens of obesity, diabetes and poor maternal health.8–10

Western health services generally approach Indigenous communities as at risk, vulnerable and lacking knowledge to solve their needs. This approach frames health promotion in Indigenous communities as new knowledge to be introduced by external service providers.11 12 Damage-centred health research has been a source of distress for Indigenous communities,13 who feel that focusing on their weaknesses and negative aspects reinforces a sense of inferiority.11 Emerging Indigenous scholars have challenged hegemonic paradigms and methodologies in academic discourse and policies.14–18 They have promoted particular ethical considerations for research involving Indigenous groups.19–22 Indigenous scholarship and increasing international recognition of cultural diversity since the 1990s have revalued Indigenous knowledge and argued for a more active role of Indigenous peoples in defining health actions in their communities.23 Emerging evidence suggests that active involvement of Indigenous participation in health promotion increases access to care and improves health outcomes in these communities.24

The practical consequence for contemporary healthcare is increased awareness and valuing of cultural diversity (cultural sensitivity) and the accommodation of strategies to provide health services in spite of cultural differences (cultural competence).25 26 Although well intended, these adjustments nonetheless maintain Western cultural dominance in health decisions of what has to be done, how to do it and whether it is done at all.26 27

Indigenous movements in Latin America advocate for intercultural dialogue to open space for non-Western standpoints and to transform structures of exclusion and marginalisation.5 28 Intercultural dialogue involves dynamic communication through which individuals, groups, or organisations with multiple cultural backgrounds converge to work out solutions around a shared concern, in our case, poor maternal health outcomes.29–31 Modern participatory research recognises that knowledge creation is the result of a partnership in which stakeholder perspectives contribute at an equal level of respect.32 33

We present the experience of the Centro de Investigación de Enfermedades Tropicales (CIET) during participatory research to improve maternal health with Indigenous communities in Mexico’s Guerrero State. This process aimed to open an intercultural dialogue by respecting Indigenous skills and customs and recognising the needs of service providers for scientific evidence of the value of traditional midwives. We describe three steps as examples of an ongoing effort to open the dialogue.

The setting

Guerrero is Mexico’s second poorest state and one of five with the largest Indigenous populations.34 Some 14% (456.774) of residents speak an Indigenous language, mainly Nahua, Na savi/Mixteco, Me’phaa/Tlapaneco, or Nancue ñomndaa/Amuzgo.35 Indigenous groups have different degrees of acculturation and most live in nuclear families in rural areas or small villages in the centre and south of the state. They subsist on migrant labour and small-scale agriculture, receiving less than the average regional wage (about US$40 per month).36 Government and private health services offer only Western birthing practices. Services are underfunded and poorly staffed.37 Traditional Indigenous midwives (parteras tradicionales) are the providers of choice for most Indigenous women, particularly in remote villages where they are the only skilled practitioners available for antenatal and delivery care. But traditional Indigenous midwifery has become attenuated and does not on its own guarantee healthy childbirth in all cases. Official health policies in Guerrero have deliberately disrupted traditional birthing systems, preventing registration of births attended by traditional midwives (and thus withholding state child support triggered by birth registration) and providing cash incentives to women who use hospital-based services. Lack of collaboration between traditional midwives and Western health services now hinders timely referral to well resourced facilities with access to emergency and obstetrically indicated surgical interventions. Pregnant Indigenous women fall between two weakened systems, one weakened by poor resourcing and inefficiencies, the other by policies of acculturation.38

Indigenous birthing systems frame biological dimensions within a specific cultural background.39 While Western science might focus first on access to obstetric services or routine diagnostic tests, Indigenous midwifery might begin with protective rituals of fertility or counselling the family on self-care practices. Indigenous women in Southern Guerrero prefer home deliveries and often shun Western obstetric care in fear of routine practices considered disrespectful in their culture.37 In this context, maternal mortality is 10 times higher in Indigenous communities than it is in the rest of the state.40

Building trust and a safe space for partnership

Since the 1980s, cross-cultural approaches to safe birth have called for ‘fruitful accommodation’ of traditional birthing systems.41 The question is how to achieve this. CIET’s experience can contribute to answering this question. As part of its decades-long relationship with Nancue ñomndaa (Amuzgo) communities in the municipality of Xochistlahuaca in Guerrero, researchers at CIET, in the Universidad Autónoma de Guerrero, responded to a 2008 request from these communities to help them address poor maternal health. The research team philosophy included respect for Indigenous cultures as the starting point and absolute requirement for all activities in research. The consequent mutual respect facilitated building trust and establishing a safe space for exploring this complex issue, amidst the tense interface between the Western health system and Indigenous communities.

Respect is an essential condition allowing participants to feel they can open up and push the limits and certainties of their own system in the discussion of shared interests and goals.42 43 Building trust is ongoing and time consuming, and benefits from a clear framework for the dialogue.44 In this case, like in others,45 self-reflexivity guided our work under the principles of cultural safety.33 Maori nurses developed the notion of cultural safety in the late 1980s in New Zealand.46 It invited researchers to recognise the colonial and historical context of health disparities and the impact their own cultural identity and assumptions had in perpetuating these disparities.47 Culturally safe healthcare would improve maternal health, while respecting or fortifying patient cultural identity.48 In consequence, the project deviated from prevailing biomedical assumptions that attempted to replace or ban traditional practices.

After obtaining ethics approval in both Mexico and Canada, Indigenous participants and CIET researchers designed a baseline survey in participatory workshops. They adjusted standard epidemiological tools to the language and concepts of Indigenous communities, to better understand the role of authentic traditional midwives and birth experiences of Indigenous women. Trained Indigenous fieldworkers conducted a baseline survey in 2008 among 1723 women between the ages of 15 and 49 who were pregnant during the previous three years. They identified and interviewed 63 traditional midwives, respectfully titled Nna’, most of whom were over 50 years of age, and whose authority rested on proved service to their patients. The Indigenous midwives described part of their role as assisting women during pregnancy and homebirth; one half of them had personally taken their patients to the hospital when additional care was needed. All still conducted household visits as their age and health permitted. And their patients paid them what they could afford, which was most often nothing.

The survey revealed that 59% (938/1589) of pregnant Indigenous women received advice and care from traditional midwives, including those who delivered with Western doctors. Based on birth order analysis, Indigenous midwife-assisted home births had declined over the previous decade to around 48% (659/1378). During deliveries in hospital, most Indigenous mothers did not have translation (68%, 468/692) and few could choose traditional positions for delivery (36%, 249/697). Birth complications such as self-reported perineal trauma were less frequent in traditional midwife-assisted births (24%, 120/656) than in births assisted by a doctor or nurse (39%, 210/543).37 Women were more likely to attend for antenatal care in health units if a traditional midwife had told them to do so, and most women and their families accepted midwife advice to deliver in a Western healthcare unit.

The survey results confirmed the cultural alienation experienced by women in government health facilities. The evidence suggested that traditional midwifery could have a positive role in these communities. Indigenous participants felt encouraged to engage further in research, recognising researcher commitment to understand their traditions instead of attempting to replace their customs. Increased mutual trust set up the next step, which focused on a collaboration to support the role of traditional midwives.

Listen and adjust: the Xochistlahuaca pilot

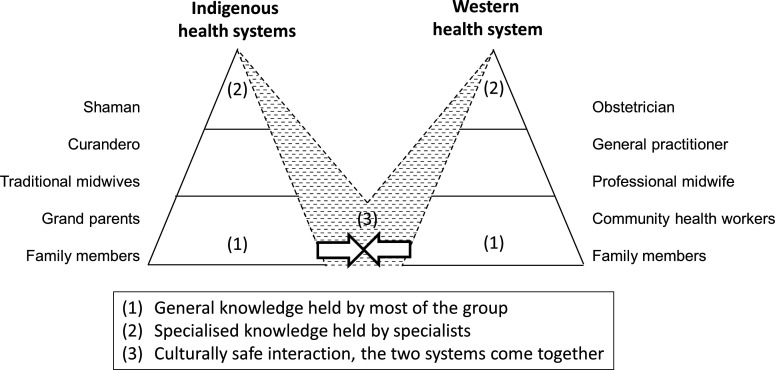

Zuluaga described intercultural dialogue between Indigenous and Western healthcare as a bridge between two healthcare pyramids (figure 1).49 The biggest potential for interaction between health systems is at the family and primary healthcare levels, where individual’s knowledge and practices are linked mostly to personal experiences (base of the pyramids). This can happen, for example, in the promotion of preventive practices or care for uncomplicated births by traditional midwives. Moving up through secondary to tertiary levels, knowledge becomes more specialised and is held by fewer practitioners with higher levels of formal training using increasingly complex technologies. CIET researchers, traditional midwives and Indigenous community health promoters together designed and piloted an intervention to support traditional midwives’ role at the base of the pyramid.50 Sixteen Indigenous traditional midwives requested facilities for simple birth centres, where they could train new apprentices, assist pregnant women and attend births. They also requested logistical support from a community health promoter linked with the project.

Figure 1.

Scheme to represent the interaction between Indigenous and Western health systems.

The goal was to generate evidence that showed the potential of traditional concepts and practices, helping participants to go beyond the terminology and concerns of their Western counterparts while identifying opportunities and barriers for collaboration. The pilot was an opportunity to listen reflexively and to adjust lexicon around culturally safe maternal healthcare. Lexicon adjustment goes beyond a simple translation of words.51 It requires listener reflexivity and experience to internalise the contents.42 In this case, first understanding the concepts of traditional midwifery and positive birth experiences, and then incorporating and testing the meaning of culturally coherent responses for maternal health. Represented as a dashed shadow in figure 1, these are opportunities for mutual learning and transformation in which both systems might expand their boundaries.

Data from a CIET survey after the intervention showed similar levels of pregnancy complications between women in exposed communities (24/94) and controls (65/252; OR 0.99, 95% CI 0.52 to 1.71), but substantially reduced birth complications (9/91 exposed and 57/248 controls; OR 0.37, 95% CI 0.11 to 0.73). The research team hypothesised that increased profile of traditional midwives led to reduced unattended deliveries and that improved logistical support in the intervention area improved referrals for high-risk women. This pilot study built local capacity to apply methods founded on a substantial history of pragmatic trials in the study of traditional midwifery.50 52

Codesign, evaluate and discuss: the four-municipality trial

With the pilot data suggesting acceptability and safety of an intervention that strengthens traditional midwives, the team designed a cluster randomised controlled trial in which traditional midwives would extend further their authoritative role.50 The goal of codesign was to allow each party to bring what they are best at, be it design a randomised control trial or manage spiritual content or counselling men. The cultural authorities of participating Indigenous communities and the ethics committees at CIET and McGill University approved this step.

In four predominantly Indigenous municipalities with access to usual healthcare, the trial compared maternal health outcomes of intervention (Xochistlahuaca and Acatepec) and control (San Luis Acatlán and Atlixtac) communities. In the intervention communities, traditional midwives received support to recover and foster their traditional role. Intervention midwives received a small stipend, a bursary to train an apprentice and the support of an intercultural broker to facilitate interaction with Western health personnel. Additionally, two workshops for health personnel in intervention municipalities sought to improve their understanding of and attitudes towards traditional midwives.

Michie described intercultural brokerage as change agents placed between two cultures and with the ability to resolve the differences that keep them apart.53 The training of 17 intercultural brokers drew on similar experience in Colombia.54 In Guerrero, brokers were community-nominated young people who learnt about primary healthcare, recovery and protection of Indigenous culture, and conservation of their territory. After the course, intercultural brokers went back to their communities to collaborate with traditional midwives, increasing their presence in the communities and bridging the language and cultural gap with Western health services.

A mid-term evaluation used a narrative approach to illustrate positive changes described by participants. Traditional midwives reported hope in cultural continuity through their apprentices and renewed recognition of traditional midwifery among communities.55 After the intervention finished in 2017, we used fuzzy cognitive mapping to portray traditional midwife knowledge on maternal health. The maps identified several birth risks including a web of Indigenous concepts of disease—‘frío’ (cold or coldness of the womb), ‘espanto’ (fright), and ‘coraje’ (anger)—abandonment of traditional practices of self-care, women’s mental health and gender violence. Participants described culturally coherent responses to these risks including rituals, medicinal plants, massages, midwives counselling of husbands and other care practices connected with their culture.56

The final statistical analysis of the randomised controlled trial, to be reported in a separate publication, will incorporate traditional midwifery knowledge as described in the fuzzy cognitive maps as prior knowledge in the statistical models, in an extension of Bayesian procedures.57 This allows a space for Indigenous voices even in the very technical matter of effect estimation and significance testing.

Limitations and challenges

Intercultural dialogue is context-specific and possible only with researcher attitudes of openness, engagement and commitment to local impact. Here, we recount three steps describing our progress: (1) trust building; (2) listener reflexivity and lexicon adjustment; and (3) codesign, evaluation and discussion. But these steps are not mechanistic or invariable, and other contexts might need additional steps.

The case we describe required long term commitment and took place over more than a full decade. Financial restrictions or changes in the internal dynamics of stakeholders can change relationships over this time. In our case, the researcher’s strong institutional commitment to equity and partnership with Indigenous communities facilitated continuity.

Sustainability of change is hard to guarantee. Although intercultural dialogue opens the door to transformation, structural change of inequity and marginalisation rooted in historical causes might require time. Initial commitment with cultural safety attempts to have stronger autonomous communities able to foster these transformations.

The overall project attempts to increase respectful interaction between local health personnel and traditional midwives. We involved health personnel in an incremental way. Intercultural brokerage supported individual contacts, and workshops provided sensitisation training and a forum for discussion. In its role as a leading graduate health training institution in Guerrero, CIET also trains future health providers, managers and planners in the state. The randomised controlled trial will hopefully produce local evidence to show the health and social value of traditional midwives. It is too early to say something definitive about system change, but we can identify components recognised as contributors to this.58 The project has increased understanding of the issues around maternal health using systems analysis (fuzzy cognitive maps) to incorporate community perspectives; it has developed a team of Indigenous and non-indigenous people able to foster action, and it has achieved ‘small wins’ that can accumulate and embolden stakeholders to pursue bigger changes.

Our proposal of intercultural dialogue is not an Indigenous methodology. It reflects the experiences of a small group of researchers. It does align, however, with previous work of Indigenous elders and researchers who developed tools and procedures that fit with traditional concepts and values,18 59 and who have highlighted the need of ‘two eyed seeing.’24 60 The commitment, approval and full participation of traditional midwives made the researchers feel confident that they considered this work appropriate.

The concept of cultural safety sometimes assumes one-way acculturation— overriding of Indigenous cultures by the dominant culture—and places the potential for disrespect on one side of the cultural divide.61 We recognise it is possible to fall short of intercultural dialogue on both sides; therefore, there is a need for ongoing reflection. Shallow consultations, in which traditional contents are not made comprehensible in Western understanding, may be used as a way to justify external interventions.28

Conclusion

The experience of the CIET team shows that intercultural dialogue is feasible and contributes to improving maternal health outcomes. When the project began, Indigenous views and knowledge were generally ignored in Western health services. Support of traditional midwifery and intercultural brokerage initiated the interactions between traditional midwives and Western health services. The scientific evidence of positive impact of traditional midwives on maternal health focus on primary care and improved referral. Stronger traditional midwives are now in a better position to take their own steps towards further interactions with service providers. High-quality healthcare requires skilled and well-supplied facilities but also respectful practices that understand cultural strengths.

Intercultural dialogue moves away from almost a century of retraining traditional midwives to use them as accessory resources for Western healthcare in underserved areas. Our approach recognises that Indigenous midwives and their traditional knowledge can be agents of change. Although this approach will need to be tested in different contexts, intercultural dialogue offers an opportunity to improve health outcomes by combining the strengths of different cultures.

Acknowledgments

The traditional midwives generously shared their knowledge throughout the research. Their commitment to women’s health in their communities will remain an inspiration beyond the limits of this project. The apprentices and intercultural brokers represent our hopes for a new time in which the shadows of colonisation might fade or even disappear in the light of intercultural dialogue. The Indigenous communities participating in the project, led by their traditional authorities, contributed to systematising knowledge and to promoting action. Abraham de Jesús García and Nadia Maciel Paulino collaborated intensely as field coordinators during the intervention of the randomised controlled trial. Robert Ledogar advised the definition of the intervention to support Indigenous midwives in 2015. Alba Meneses, David Gazga, Alejandro Balanzar, Miguel Flores, José Legorreta and the research team at CIET greatly collaborated to make the work with traditional midwives in Guerrero possible. Germán Zuluaga, Carolina Amaya, Ignacio Giraldo and Juan Pimentel conducted the training program for intercultural brokers. The late Ascencio Villegas Arrizón was a tireless promoter of health and well-being in Indigenous groups of Guerrero State and he supported the dialogue with traditional midwives until his death in 2012.

Footnotes

Handling editor: Seye Abimbola

Collaborators: Alba Meneses-Rentería; Abraham De Jesús García; Nadia Maciel Paulino. Centro de Investigación de Enfermedades Tropicales (CIET) at the Universidad Autónoma de Guerrero.

Contributors: IS drafted the document and synthesised the steps for intercultural dialogue. NA, SP-S and GZ participated in the codesign of the interventions and established the basis of the intercultural dialogue approach. AC, AMC and DL contributed with their critical appraisal of the approach and its theoretical considerations. All authors participated in the review and construction of this manuscript.

Funding: The pilot received support from UBS Optimus Foundation. CONACyT, the National Council of Science and Technology of Mexico funded the BMx2 randomised controlled trial (PDCPN-2013-214858). The Quebec Population Health Research Network and the Faculty of Medicine of McGill University provided support for fieldwork. Ceiba Foundation and the Center of Intercultural Medical Studies in Colombia, and the Fonds de recherche du Québec Santé (255253) supported the analysis of the randomised controlled trial.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: Data from the surveys are available upon reasonable request and after authorization from the participating communities.

References

- 1.International Council for Science ICSU series on science for sustainable development No. 4: science, traditional knowledge and sustainable development, 2002. Available: http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0015/001505/150501eo.pdf [Accessed 18 Oct 2018].

- 2.Abbott R. Documenting traditional medical knowledge, 2014. Available: http://www.wipo.int/export/sites/www/tk/en/resources/pdf/medical_tk.pdf[Accessed 30 Apr 2014].

- 3.World Health Organization Regional office for the Western Pacific. A report of the consultation meeting on traditional and modern medicine: harmonizing the two approaches, 22-26 November 1999, Beijing, China. Manila, Phillipinas: 1999. Available: http://iris.wpro.who.int/handle/10665.1/5573 [Accessed 19 Apr 2015].

- 4.National Agency for Drug and Food Control, World Health Organization . Trips, CBD and traditional medicines: concepts and questions. Report of an ASEAN workshop on the trips agreement and traditional medicine, 2001. Available: http://apps.who.int/medicinedocs/en/d/Jh2996e/5.html [Accessed 18 Oct 2018].

- 5.Walsh C. Interculturalidad, plurinacionalidad Y decolonialidad: LAS insurgencias político-epistémicas de refundar El Estado. Tabula Rasa 2008:131–52. 10.25058/20112742.343 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Division for Social Policy and Development Secretariat . Secretariat of the Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues. State of the World’s indigenous peoples. New York, 2017. Available: https://www.un.org/development/desa/indigenouspeoples/wp-content/uploads/sites/19/2017/12/State-of-Worlds-Indigenous-Peoples_III_WEB2018.pdf [Accessed 1 Jun 2018].

- 7.Restrepo E, Rojas A. Infelxión decolonial: fuentes, conceptos Y cuestionamientos. Popayán, Colombia: Universidad del Cauca, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 8.King M, Smith A, Gracey M. Indigenous health part 2: the underlying causes of the health gap. Lancet 2009;374:76–85. 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60827-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gracey M, King M. Indigenous health Part 1: determinants and disease patterns. Lancet 2009;374:65–75. 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60914-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lalonde AB, Butt C, Bucio A. Maternal health in Canadian Aboriginal communities: challenges and opportunities. J Obstet Gynaecol Can 2009;31:956–62. 10.1016/S1701-2163(16)34325-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tuck E. Suspending damage: a letter to communities. Harv Educ Rev 2009;79:409–28. 10.17763/haer.79.3.n0016675661t3n15 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.World Health Organization The regional strategy for traditional medicine in the Western Pacific (2011-2020), 2012. Available: http://www.wpro.who.int/publications/2012/regionalstrategyfortraditionalmedicine_2012.pdf [Accessed 18 Oct 2018].

- 13.Cochran PAL, Marshall CA, Garcia-Downing C, et al. Indigenous ways of knowing: implications for participatory research and community. Am J Public Health 2008;98:22–7. 10.2105/AJPH.2006.093641 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McGregor D, Restoule J-P, Johnston R. Indigenous research: theories, practices, and relationships. Toronto, ON, Canada: Canadian Scholars, an imprint of CSP Books Inc, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Windchief S, San Pedro T. Applying Indigenous research methods. New York, United States: Routledge, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Smith LT. Decolonizing methodologies: research and indigenous peoples. 2 edn London: Zed Books, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Denzin NK, Lincoln YS, Smith LT. Handbook of critical and indigenous methodologies. Los Angeles: Sage, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Williams M. Ngaa-bi-nya Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander program evaluation framework. Eval J Australas 2018;18:6–20. 10.1177/1035719X18760141 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Canadian Institutes of Health Research, Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada, Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada . TCPS 2 Chapter 9 In: Tri-Council policy statement: ethical conduct for research involving humans, 2014: 109–38. http://www.pre.ethics.gc.ca/eng/policy-politique/initiatives/tcps2-eptc2/Default/ [Google Scholar]

- 20.National Aboriginal Health Organization (NAHO) OCAP®: ownership, control, access and possession. OCAP® is a registered trademark of the first nations information governance centre (FNIGC, 2007. www.FNIGC.ca/OCAP [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zuluaga G. Una ética para la investigación médica con comunidades indígenas : Vélez A, Ruiz A, Torres M, Retos Y dilemas de Los comités de ética en investigación. Bogotá: Editorial Universidad del Rosario, 2013: 259–81. http://media.wix.com/ugd/cb47c9_d790340d497847e58f5505518c122b24.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 22.Macaulay AC, Delormier T, McComber AM, et al. Participatory research with native community of Kahnawake creates innovative code of research ethics. Can J Public Health 1998;89:105–8. 10.1007/BF03404399 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Huria T, Palmer SC, Pitama S, et al. Consolidated criteria for strengthening reporting of health research involving Indigenous peoples: the consider statement. BMC Med Res Methodol 2019;19:173. 10.1186/s12874-019-0815-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Allen L, Hatala A, Ijaz S, et al. Indigenous-led health care partnerships in Canada. CMAJ 2020;192:E208–16. 10.1503/cmaj.190728 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Aylett R, Hall L, Tazzyman S, et al. Werewolves, cheats, and cultural sensitivity : Lomuscio A, Scerri P, Bazzan A, et al., Proceedings of the 13th International Conference on autonomous agents and multi-agent systems (AAMAS 2014. Paris: International Foundation for Autonomous Agents and Multiagent Systems, 2014: 1085–92. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kirmayer LJ. Rethinking cultural competence. Transcult Psychiatry 2012;49:149–64. 10.1177/1363461512444673 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pon G. Cultural competency as new racism: an ontology of forgetting. J Progress Hum Serv 2009;20:59–71. 10.1080/10428230902871173 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Interculturality DG, Dietz G. Interculturality : Callan H, The International encyclopedia of anthropology. Oxford, UK: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, 2018: 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Council of Europe White paper on Intercultural dialogue: living together as equals in dignity, 2008. Available: https://www.coe.int/t/dg4/intercultural/source/whitepaper_final_revised_en.pdf [Accessed 1 Jun 2018].

- 30.Ganesh S, Holmes P. Positioning intercultural dialogue—Theories, pragmatics, and an agenda. J Int Intercult Commun 2011;4:81–6. 10.1080/17513057.2011.557482 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pérez Ruíz ML, Argueta AV. Saberes indígenas Y dialogo intercultural. Cult y Represent Soc 2011:31–56. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Andersson N. Participatory research-A modernizing science for primary health care. J Gen Fam Med 2018;19:154–9. 10.1002/jgf2.187 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cameron M, Andersson N, McDowell I, et al. Culturally safe epidemiology: oxymoron or scientific imperative.. Pimatisiwin J Aborig Indig Community Heal 2010;8:89–116. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Consejo Nacional de Evaluación de la Política de Desarrollo Social Indicadores de pobreza, 2008-2018 (nacional Y estatal), 2020. https://datos.gob.mx/busca/dataset/indicadores-de-pobreza-2008-2018-nacional-y-estatal [Google Scholar]

- 35.Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía de México Population aged 5 years and over who speaks some Indigenous language. Available: http://en.www.inegi.org.mx/temas/lengua/ [Accessed 10 Jun 2018].

- 36.Meneses S, Pelcastre B, Vega M. Maternal mortality and the coverage, availability of resources, and access to women’s health services in three indigenous regions of Mexico: Guerrero Mountains, Tarahumara Sierra, and Nayar : Schwartz DA, Maternal death and pregnancy-related morbidity among Indigenous women of Mexico and central America. Cham: Springer International Publishing, 2018: 169–88. [Google Scholar]

- 37.de Jesús-García A, Paredes-Solís S, Valtierra-Gil G, et al. Associations with perineal trauma during childbirth at home and in health facilities in Indigenous municipalities in southern Mexico: a cross-sectional cluster survey. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2018;18:198. 10.1186/s12884-018-1836-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mills L. The limits of trust: the millennium development goals, maternal health, and health policy in Mexico. Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chalmers B. African birth: childbirth in cultural transition, 1990. Available: http://www.popline.org/node/384026 [Accessed 19 Jan 2019].

- 40.Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía de México Mortalidad General. Available: https://www.inegi.org.mx/sistemas/olap/Proyectos/bd/continuas/mortalidad/MortalidadGeneral.asp [Accessed 28 Mar 2019].

- 41.Jordan B. Birth in four cultures: a crosscultural investigation of childbirth in Yucatan, Holland, Sweden, and the United States. 4 edn IL: Waveland Press, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Eberhard C. Rediscovering education through intercultural dialogue : Contribution to the international meeting of experts on cultural diversity and education. Brussels, 2008. http://www.dhdi.free.fr/recherches/horizonsinterculturels/articles/eberhardeducation.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 43.Leeds-Hurwitz W, Dialogue I. Intercultural Dialogue : Tracy K, Ilie C, Sandel T, The international encyclopedia of language and social interaction. Hoboken, NJ, USA: John Wiley & Sons, Inc, 2015: 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jagosh J, Bush PL, Salsberg J, et al. A realist evaluation of community-based participatory research: partnership synergy, trust building and related ripple effects. BMC Public Health 2015;15:725. 10.1186/s12889-015-1949-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nicholls R. Research and Indigenous participation: critical reflexive methods. Int J Soc Res Methodol 2009;12:117–26. 10.1080/13645570902727698 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Polaschek NR. Cultural safety: a new concept in nursing people of different ethnicities. J Adv Nurs 1998;27:452–7. 10.1046/j.1365-2648.1998.00547.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Allan B, Smylie J, peoples F. First peoples, second class treatment. The role of racism in the health and well-being of Indigenous peoples in Canada. Toronto, ON, 2015. http://www.wellesleyinstitute.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/02/Summary-First-Peoples-Second-Class-Treatment-Final.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 48.Papps E, Ramsden I. Cultural safety in nursing: the New Zealand experience. Int J Qual Health Care 1996;8:491–7. 10.1093/intqhc/8.5.491 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zuluaga G, Correal-Muñoz CA. Panorama actual de las medicinas tradicionales : Medicinas tradicionales: introducción al estudio de Los sistemas tradicionales de salud Y SU relación Con La medicina moderna. Bogotá: Universidad El Bosque, 2002: 13–28. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sarmiento I, Paredes-Solís S, Andersson N, et al. Safe birth and cultural safety in southern Mexico: study protocol for a randomised controlled trial. Trials 2018;19:354. 10.1186/s13063-018-2712-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rubel AJ, O’Nell C. Dificultades para expresar al médico los trastornos que aquejan al paciente: La enfermedad del susto, como ejemplo. Boletín la Of Sanit Panam 1979;87:103–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Andersson N. Proof of impact and pipeline planning: directions and challenges for social audit in the health sector. BMC Health Serv Res 2011;11:S16. 10.1186/1472-6963-11-S2-S16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Michie M. Understanding culture brokerage : Working Cross-culturally: identity learning, border crossing and culture brokering. Rotterdam: Sense Publishers, 2014: 83–106. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Amaya C. Gestores Comunitarios de Salud: Una experiencia pedagógica piloto en La Universidad del Rosario. Rev Ciencias la Salud 2006;4:33–40. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Dart J, Davies R. A dialogical, story-based evaluation tool: the most significant change technique. Am J Eval 2003;24:137–55. 10.1177/109821400302400202 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sarmiento I, Paredes-Solís S, Loutfi D, et al. Fuzzy cognitive mapping and soft models of Indigenous knowledge on maternal health in Guerrero, Mexico. BMC Med Res Methodol 2020;20:125. 10.1186/s12874-020-00998-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Dion A, Joseph L, Jimenez V, et al. Grounding evidence in experience to support people-centered health services. Int J Public Health 2019;64:797–802. 10.1007/s00038-018-1180-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Foster-Fishman PG, Watson ER. The able change framework: a conceptual and methodological tool for promoting systems change. Am J Community Psychol 2012;49:503–16. 10.1007/s10464-011-9454-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kirkness VJ, Barnhardt R. First nations and higher education: the four R’s – respect, relevance, reciprocity, responsibility. J Am Indian Educ 1991;30. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Bartlett C, Marshall M, Marshall A. Two-eyed seeing and other lessons learned within a co-learning journey of bringing together Indigenous and mainstream knowledges and ways of knowing. J Environ Stud Sci 2012;2:331–40. 10.1007/s13412-012-0086-8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Johnstone M-J, Kanitsaki O. An exploration of the notion and nature of the construct of cultural safety and its applicability to the Australian health care context. J Transcult Nurs 2007;18:247–56. 10.1177/1043659607301304 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]