Abstract

Objective

Our objective was to examine risk factors associated with development of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) among women with endometrial cancer who underwent surgical staging with or without oophorectomy.

Methods

This is a retrospective study that evaluated endometrial cancer cases that underwent surgical staging (n = 666) and endometrial hyperplasia cases that underwent hysterectomy-based treatment (n = 209). This study included 712 oophorectomy cases and 163 nonoophorectomy cases. Archived records were reviewed for participant demographics, medical comorbidities, operative notes, histology results, and radiology reports for NAFLD. Cumulative risks of NAFLD after surgical operation were correlated to demographics and medical comorbidities.

Results

The cumulative prevalence ofNAFLD in 875 women with endometrial tumor was 14.1%, 20.5%, and 38.4% at 1, 2, and 5 years after surgical operation, respectively. On multivariate analysis, after controlling for age, ethnicity, body mass index, medical comorbidities, tumor type, hormonal treatment pattern, and oophorectomy status, age younger than 40 years (2-y cumulative prevalence, 26.6% vs 16.8%; hazard ratio [HR], 1.85; 95% CI, 1.27–2.71; P = 0.001) and age 40 to 49 years (2-y cumulative prevalence, 23.1% vs 16.8%; HR, 1.49; 95% CI, 1.08–2.04; P = 0.015) remained significant predictors for developing NAFLD after surgical operation compared with age 50 years or older. Oophorectomy was an independent predictor for increased risk of NAFLD (20.9% vs 15.9%; HR, 1.70; 95% CI, 1.01–2.86; P = 0.047). In addition, NAFLD was significantly associated with postoperative development of diabetes mellitus (39.2% vs 15.3%; HR, 2.26; 95% CI, 1.52–3.35; P < 0.0001) and hypercholesterolemia (34.3% vs 17.5%; HR, 1.71; 95% CI, 1.12–2.63; P = 0.014).

Conclusions

Oophorectomy in young women with endometrial cancer significantly increases the risk of NAFLD. This is associated with development of diabetes mellitus and hypercholesterolemia after oophorectomy.

Keywords: Endometrial cancer, Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, Diabetes, Hypercholesterolemia, Obesity, Oophorectomy

Endometrial cancer is the most common gynecologic cancer in the United States. In 2015, an estimated 54,870 women will be diagnosed, and 10,170 women will die of the disease.1 A large number of endometrial cancer cases are diagnosed at the early stages, when endometrial cancer is curable with surgical treatment alone. Surgical operation remains the mainstay of initial treatment, unless the woman is not a candidate for operation.2 The standard surgical treatment of endometrial cancer includes hysterectomy and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy, with possible lymphadenectomy.2 Oophorectomy is performed given the risk of possible ovarian metastasis and synchronous or meta-chronous ovarian cancer and the possible role of ovarian hormone production in endometrial carcinogenesis.3,4

A consequence of oophorectomy is that premenopausal women with endometrial cancer experience an absence of ovarian hormones, including estrogen. Estrogen deprivation impacts female health parameters, including lipid metabolism.5 A link between increased risk of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) and advanced age—especially after spontaneous menopause—has been observed.6 NAFLD is known to be not only a hepatic manifestation of metabolic syndrome related to obesity, diabetes mellitus, hypertension, and hypercholesterolemia but also a possible risk factor for cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma.7–9 Therefore, profiling the characteristics and risk factors for developing NAFLD after oophorectomy in young women with endometrial cancer would be helpful in understanding the pathophysiology and management of endometrial cancer. The aim of the current study was to evaluate the risk factors associated with NAFLD among women with endometrial cancer who underwent oophorectomy, compared with those who did not undergo oophorectomy.

METHODS

Clinical information

After Institutional Review Board approval was obtained from the University of Southern California and the Los Angeles County Medical Center, the institutional database for endometrial cancer was used to identify cases. Inclusion criteria were as follows: primary endometrial cancer, histologic diagnosis confirmed by hysterectomy-based surgical staging with or without bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy, and management and follow-up at the Los Angeles County Medical Center between January 1, 2000 and December 31, 2012. Metastatic cancer to the endometrium from other origins and uterine sarcoma cases were not included in the study. In addition, data from endometrial hyperplasia cases that underwent hysterectomy-based surgical treatment were collected. This group was chosen because endometrial hyperplasia is a well-known precursor of endometrial cancer, sharing similar participant demographics and characteristics. Part of our study population has been described within the context of our prior studies.10–13

Among cases eligible for analysis, medical records were further examined to abstract the following variables of interest: (i) participant demographics; (ii) histopathologic findings; (iii) laboratory results and imaging findings; (iv) treatment patterns; and (v) survival outcome. Demographic characteristics analyzed included age at surgical operation, ethnicity, body mass index (BMI), and medical comorbidities such as diabetes mellitus, hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, alcohol consumption, and liver disease. These medical comorbidities were recorded at the time of tumor diagnosis and during follow-up after surgical operation. For pathologic findings, detailed information was obtained from pathology reports for surgical staging and hysterectomy: histology subtype, tumor grade, and stage. Cancer stage was reclassified based on the recent International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics system (revised in 2009).14 Laboratory tests abstracted from records included the following liver function tests collected at the time of NAFLD diagnosis: aspartate aminotransferase (AST), alanine aminotransferase (ALT), alkaline phosphatase (ALP), total bilirubin, total protein, and albumin. Radiology reports for imaging modalities used to diagnose NAFLD were reviewed, and the following variables were recorded: type of imaging, presence or absence of NAFLD, cholelithiasis, cholecystitis, cirrhosis, or liver metastasis. Treatment patterns abstracted from medical records included details of surgical staging and the presence or absence of estrogen therapy (ET) after surgical operation. Survival outcomes abstracted from records included diseasefree survival (DFS) and overall survival (OS). DFS was determined as the time interval between the date of surgical operation for endometrial cancer and the date of first recurrence or the last date of follow-up. OS was calculated as the time interval between the date of surgical operation and the date of death related to endometrial cancer or the last date of follow-up.

Definition

Age at surgical operation for endometrial tumor was grouped as follows: younger than 40 years, 40 to 49 years, and 50 years or older. BMI was classified as lower than 30 kg/ m2, 30 to 39.9 kg/m2, and 40 kg/m2 or higher. Medical comorbidity was classified as no comorbidity (none), diagnosed before surgical operation for endometrial cancer (preexisting), and diagnosed during follow-up after surgical operation (after surgical operation). Surgical menopause was defined as having had bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy (or unilateral oophorectomy among women who previously had had one ovary removed). NAFLD was defined as radiographic evidence of increased hepatic echogenicity on ultrasonography or attenuation of the liver on CT.15 Because development of NAFLD is a time-dependent event, the time interval between the date of surgical operation for endometrial cancer and the date of NAFLD diagnosis was defined as time to NAFLD.

Based on our daily practice of endometrial cancer management, women generally undergo systemic imaging with CT and/or ultrasonography at the time of initial endometrial cancer diagnosis before they undergo surgical staging. During postoperative follow-up, complete blood count and comprehensive metabolic panel (including liver function tests) are routinely examined at each office visit (every 3 mo for the first 2 y, every 6 mo until 5 y after surgical operation, and once a year after 5 y of postoperative follow-up). Liver ultrasonographic evaluation is performed accordingly for women with abnormal liver function test results or for women complaining of pain in the upper abdomen or gastrointestinal symptoms. Systemic imaging with CT is performed whenever recurrence is suspected.

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables were assessed for normality (Kolmogorov-Smirnov test) and expressed as appropriate (mean [SD] or median [range]). Spearman’s correlation coefficient was used to determine the statistical significance of two continuous variables. One-way analysis of variance was used to compare the means of three or more groups. Categorical variables for participant demographics were evaluated with Fisher’s exact test or x2 test. For determination of statistical significance, time-dependent analysis with log-rank test was used for univariate analysis, and Cox proportional hazards regression model was used to determine the independent association of oophorectomy with NAFLD, after adjustment for other confounders. A priori covariates entered into the final model were chosen based on clinical relevance to NAFLD. These included age (≥50, 40–49, or <40 y), ethnicity (non-Hispanic vs Hispanic), BMI (<30, 30–39.9, or ≥40 kg/m2), diabetes mellitus (no diabetes, preexisting diabetes, or diabetes diagnosed after surgical operation), hypertension (no hypertension, preexisting hypertension, or hypertension diagnosed after surgical operation), and hypercholesterolemia (no hypercholesterolemia, preexisting hypercholesterolemia, or hypercholesterolemia diagnosed after surgical operation), ET (no vs yes), disease type (hyperplasia vs cancer), and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy (no vs yes). Outcomes are reported as hazard ratios (HRs) indicated for follow-up time and 95% CI relative to the indicator for each variable. DFS and OS were analyzed with log-rank test. Survival curves were constructed with the Kaplan-Meier method. P<0.05 was considered statistically significant (two-tailed). Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (version 12.0; SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL) was used for all analyses.

RESULTS

Six hundred sixty-six cases of endometrial cancer underwent hysterectomy-based surgical staging during the study period. Of those cases, 23 cases (3.5%) did not undergo bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy, and the remaining 643 cases underwent hysterectomy and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy. There were 209 cases of endometrial hyperplasia, including 140 cases (67.0%) that did not undergo bilateral salpingooophorectomy. No participant had a history of bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy. Altogether, 875 cases of endometrial tumor, including 163 cases (18.6%) that did not undergo oophorectomy, were analyzed for statistical comparisons.

Baseline participant characteristics are shown in Table 1. The mean age of the entire cohort was 50.8 years (range, 24–87 y). Most women in our study were Hispanic (68.7%) and obese (BMI ≥30kg/m2; 69.6%). At the time of endometrial tumor diagnosis, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and hypercholesterolemia were seen in 49.7%, 29.7%, and 22.4% of all women, respectively. Regular alcohol consumption was reported in three cases (0.3%). Sixteen cases (1.8%) used ET after surgical operation (mean age, 42.6 y). The median follow-up time was 28.7 months, and 60 deaths (9.3%) were related to endometrial cancer. Age at surgical operation was not correlated with follow-up time (Spearman's r = −0.03, P = 0.41).

TABLE 1.

Clinical demographics

| All (N = 875) | NAFLD+ (n = 232; 26.5%) | NAFLD− (n = 643; 72.5%) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean (SD), y | 50.8 (10.5) | 48.6 (10.1) | 51.6 (10.6) | |

| Age category, n (%) | 0.017 | |||

| ≥50 y | 496 (56.7) | 114 (49.1) | 382 (59.4) | |

| 40–49 y | 224 (25.6) | 66 (28.4) | 158 (24.6) | |

| <40 y | 155 (17.7) | 52 (22.4) | 103 (16.0) | |

| Race, n (%) | 0.001 | |||

| White | 96 (11.0) | 20 (8.6) | 76 (11.8) | |

| African | 51 (5.8) | 4 (1.7) | 47 (7.3) | |

| Hispanic | 601 (68.7) | 182 (78.4) | 419 (65.2) | |

| Asian | 127 (14.5) | 26 (11.2) | 101 (15.7) | |

| Body mass index, mean (SD), kg/m2 | 35.5 (9.3) | 36.7 (8.6) | 35.1 (9.5) | |

| Body mass index category, n (%) | 0.029 | |||

| <30 kg/m2 | 262 (30.1) | 54 (23.5) | 208 (32.4) | |

| 30–39.9 kg/m2 | 384 (44.1) | 115 (50.0) | 269 (42.0) | |

| ≥40 kg/m2 | 225 (25.8) | 61 (26.5) | 164 (25.6) | |

| Diabetes mellitus, n (%) | <0.0001 | |||

| None | 554 (63.4) | 115 (49.6) | 439 (68.4) | |

| Preexisting | 260 (29.7) | 77 (33.2) | 183 (28.5) | |

| After surgical operation | 60 (6.9) | 40 (17.2) | 20 (3.1) | |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 0.019 | |||

| None | 382 (43.7) | 88 (37.9) | 294 (45.8) | |

| Preexisting | 434 (49.7) | 121 (52.2) | 313 (48.8) | |

| After surgical operation | 58 (6.6) | 23 (9.9) | 35 (5.5) | |

| Hypercholesterolemia, n (%) | 0.001 | |||

| None | 625 (71.5) | 147 (63.4) | 478 (74.5) | |

| Preexisting | 196 (22.4) | 58 (25.0) | 138 (21.5) | |

| After surgical operation | 53 (6.1) | 27 (11.6) | 26 (4.0) | |

| Estrogen therapy, n (%) | 0.58 | |||

| No | 859 (98.2) | 229 (98.7) | 630 (98.0) | |

| Yes | 16 (1.8) | 3 (1.3) | 13 (2.0) | |

| Disease type, n (%) | 0.21 | |||

| Hyperplasia | 209 (23.9) | 48 (20.7) | 161 (25.0) | |

| Cancer | 666 (76.1) | 184 (79.3) | 482 (75.0) | |

| Bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy, n (%) | 0.07 | |||

| No | 163 (18.6) | 34 (14.7) | 129 (20.1) | |

| Yes | 712 (81.4) | 198 (85.3) | 514 (79.9) |

χ2 test for P values: NAFLD+ group versus NAFLD− group (missing for body mass index, four cases; missing for each medical comorbidity, one case). NAFLD, nonalcoholic fatty liver disease.

Covariates associated with age were examined. Age was associated with ethnicity (mean age: white, 50.2 y; African, 51.6 y; Hispanic, 50.2 y; Asian, 54.0 y; P = 0.002), body mass index (mean body mass index: age < 40 y, 40.2 kg/m2; age 4049 y, 34.5 kg/m2; age ≥50 y, 34.5 kg/m2; P < 0.001), hypertension (mean age: none, 47.0 y; preexisting, 54.5 y; diagnosed after surgical operation, 48.7 y; P < 0.001), hypercholesterolemia (mean age: none, 49.7 y; preexisting, 54.6 y; diagnosed after surgical operation, 49.6 y; P < 0.001), oophorectomy at time of surgical operation (age < 40 y, 54.8%; age 40–49 y, 70.1%; age ≥50 y, 94.8%; P < 0.001), and endometrial tumor type (mean age: cancer, 52.6 y; hyperplasia, 45.2 y; P < 0.001).

NAFLD was diagnosed in 232 cases (26.5%) at the time of endometrial tumor diagnosis or during follow-up after surgical operation (Table 1). Women who developed NAFLD were younger (P = 0.017) and more often Hispanic (P = 0.001) and obese (P = 0.029). Women with NAFLD were more likely to have developed diabetes (P < 0.0001), hypertension (P = 0.019), and hypercholesterolemia (P = 0.001) after surgical operation. Characteristics of NAFLD are shown in Table 2. NAFLD at the time of initial endometrial tumor diagnosis was noted in 64 (7.3%) of 875 cases, and there was no difference in incidence across age groups (<40 y, 9.0%; 40–49 y, 7.1%; ≥50 y, 6.9%; P = 0.66). Most NAFLD cases were diagnosed after surgical operation (n = 168; 72.4%) and were commonly diagnosed by ultrasonography (76.2%). None underwent liver biopsy to diagnose NAFLD. Cholelithiasis, hepatomegaly, and cirrhosis were diagnosed in 31 cases (13.3%), 23 cases (9.9%), and 1 case (0.4%), respectively, at the time of NAFLD diagnosis. No cases of cholecystitis or liver metastasis were reported. Abnormal liver function test results (48.7%) were the most common indication for diagnostic imaging for NAFLD. Sixty-one cases (26.3%) had symptoms of NAFLD (abdominal pain, 100%; nausea and emesis, 11.9%; bloating, 4.8%). Incidental diagnosis was common and was seen in 47 (20.3%) of all NAFLD cases. The most commonly and abnormally elevated liver function test was ALT (61.9%), followed by ALP (46.5%) and AST (41.6%). Among those with elevated liver function test results, the extent of elevation was mild (median: AST, 58 IU/ L; ALT, 63 IU/L; ALP, 118 IU/L). Among cases diagnosed as NAFLD, no alcohol consumption or active hepatitis was reported. One case (0.4%) reported a remote history of hepatitis A.

TABLE 2.

Characteristics of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in endometrial cancer (n = 232)

| Fatty liver disease | |

|---|---|

| Timing of onset, n (%) | |

| Preexisting | 64 (27.6) |

| After surgical operationa | 168 (72.4) |

| Diagnostic modality, n (%)b | |

| Ultrasonography | 170 (76.2) |

| CT | 52 (23.3) |

| Magnetic resonance imaging | 1 (0.4) |

| Indication for imaging, n (%) | |

| Abnormal liver function test results alone | 113 (48.7) |

| Incidental | 47 (20.3) |

| At disease diagnosis | 30 (12.9) |

| During postoperative follow-up | 17 (7.3) |

| Symptoms alonec | 51 (22.0) |

| Symptoms plus abnormal liver function test resultsc | 10 (4.3) |

| No record | 11 (4.7) |

| Laboratory test at diagnosis | |

| Aspartate aminotransferase, median (range), U/L | 58 (41–197)d |

| Aspartate aminotransferase level, n (%) | |

| ≤40 U/L | 118 (58.4) |

| >40 U/L | 84 (41.6) |

| Alanine aminotransferase, median (range), U/L | 63 (41–298)d |

| Alanine aminotransferase level, n (%) | |

| ≤40 U/L | 77 (38.1) |

| >40 U/L | 125 (61.9) |

| Alkaline phosphatase, median (range), U/L | 118 (101–556)d |

| Alkaline phosphatase level, n (%) | |

| ≤100 U/L | 108 (53.5) |

| >100 U/L | 94 (46.5) |

| Total bilirubin, median (range), mg/dL | 1.4 (1.1–3.0)d |

| Total bilirubin level, n (%) | |

| ≤1.0 mg/dL | 198 (98.0) |

| >1.0 mg/dL | 4 (2.0) |

| Total protein, median (range), g/dL | 8.2 (8.1–8.8)d |

| Total protein level, n (%) | |

| <6.0 g/dL | 1 (0.5) |

| 6.0–8.0 g/dL | 184 (91.1) |

| >8.0 g/dL | 17 (8.4) |

| Albumin, median (range), g/dL | 5.25 (5.2–5.3)d |

| Albumin level, n (%) | |

| <3.5 g/dL | 6 (3.0) |

| 3.5–5.0 g/dL | 194 (96.0) |

| >5.0 g/dL | 2 (1.0) |

Reference ranges: aspartate aminotransferase, 10–40 U/L; alanine aminotransferase, 5–40 U/L; alkaline phosphatase, 30–100 U/L; total bilirubin, 0.0–1.0mg/dL; total protein, 6.0–8.0g/dL; albumin, 3.5–5.0g/dL.

After hysterectomy with or without oophorectomy.

Nine cases with remote history.

Symptoms included abdominal pain/bloating, nausea, and emesis.

Values are for cases with elevated liver function test results (missing for laboratory test, 30 cases).

Among NAFLD cases, 38 cases developed postoperative diabetes mellitus, and 27 cases developed postoperative hypercholesterolemia. Chronological sequences of postoperative diabetes mellitus/hypercholesterolemia and NAFLD were examined. Most NAFLD cases were antecedent to postoperative diabetes mellitus (81.6%); the median time interval from NAFLD to postoperative diabetes mellitus was 13.5 months (range, 0.1–69.3 mo). Similarly, most NAFLD cases were antecedent to postoperative hypercholesterolemia (88.9%); the median time interval from NAFLD to hypercholesterolemia was 23 months (range, 1.0–93.2 mo). This was significantly longer than time to development of diabetes mellitus (P = 0.034). Among cases of postoperative diabetes mellitus and hypercholesterolemia that were diagnosed antecedent to NAFLD, the median time interval to NAFLD diagnosis was 4.1 months for diabetes mellitus and 3.8 months for hypercholesterolemia.

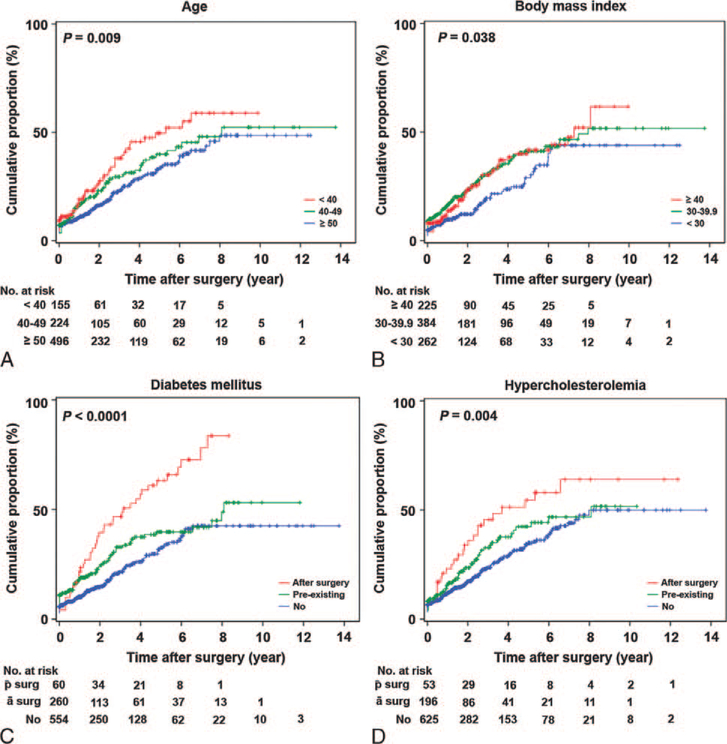

Because development of NAFLD is a time-dependent event, the cumulative risk of NAFLD after surgical operation for endometrial tumor was examined. In the entire cohort of 875 cases, the 1-year, 2-year, and 5-year cumulative risk of NAFLD after surgical operation for endometrial tumor was 14.1%, 20.5%, and 38.4%, respectively. On univariate analysis, age, BMI, diabetes mellitus, and hypercholesterolemia were significantly associated with NAFLD (all P < 0.05). Younger age was associated with development of NAFLD after surgical operation (P = 0.009; Fig. 1A). Women younger than 40 years had a significantly increased risk of NAFLD compared with women aged 50 years or older (HR, 1.64; 95% CI, 1.18–2.28). Obesity was also associated with NAFLD (P = 0.038; Fig. 1B), but the magnitude of significance was similar for BMI groups 30 to 39.9 kg/m2 (HR, 1.49) and 40kg/m2 or higher (HR, 1.46). Diabetes mellitus was the variable most strongly associated with NAFLD (P < 0.0001;Fig. 1C). Women with preexisting diabetes mellitus had increased risk of NAFLD compared with women without diabetes (HR, 1.41; 95% CI, 1.06–1.88). Diabetes mellitus diagnosed after surgical operation was associated with the greatest risk of NAFLD (HR, 2.67; 95%CI, 1.86–3.83). Similar to diabetes mellitus, women who developed postoperative hypercholesterolemia had a significantly increased risk of NAFLD compared with women without hypercholesterolemia (HR, 1.90; 95% CI, 1.26–2.87; P = 0.004; Fig. 1D).

FIG. 1.

Cumulative risk of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in endometrial cancer (log-rank test for P values). Cumulative proportional risk of fatty liver disease after surgical operation for endometrial cancer: (A) age at surgical operation for endometrial cancer, (B) body mass index, (C) diabetes mellitus, and (D) hypercholesterolemia. surg, after surgical operation; ā surg, before surgical operation.

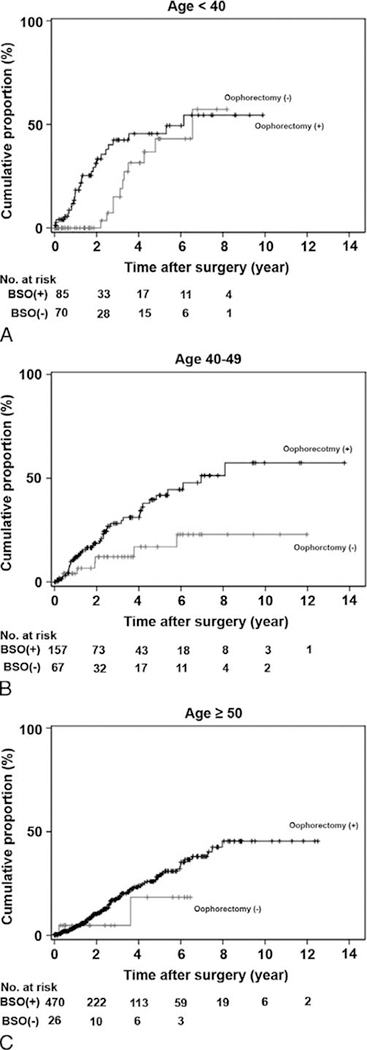

On multivariate analysis controlling for age, ethnicity, BMI, medical comorbidities, ET, tumor type, and oophorectomy type (Table 3), age younger than 40 years (HR, 1.85; P = 0.001) and age 40 to 49 years (HR, 1.49; P = 0.015) remained significant predictors for developing NAFLD compared with age 50 years or older. In addition, NAFLD was significantly associated with postoperative diabetes mellitus (HR, 2.26; P < 0.0001) and hypercholesterolemia (HR, 1.71; P = 0.014) on multivariate analysis. Lastly, oophorectomy remained an independent predictor for increased risk of developing NAFLD after surgical operation (HR, 1.70; P = 0.047). The 2-year/5-year cumulative risks of NAFLD for the oophorectomy and nonoophorectomy groups were as follows: 36.4%/49.4% and 12.2%/49.8% for age younger than 40 years (Fig. 2A); 23.9%/46.1% and 21.2%/24.9% for age 40 to 49 years (Fig. 2B); and 17.1%/34.5 and 9.8%/22.6% for age 50 years or older (Fig. 2C), respectively (log-rank test for oophorectomy effects on NAFLD stratified by age group; P = 0.015). Results of post hoc analysis for endometrial cancer are described in "Result S1" (Supplemental Digital Content 1, http://links.lww.com/MENO/A133).

TABLE 3.

Independent risk factors for nonalcoholic fatty liver disease

| Cumulative risk |

Multivariate analysis |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2-y cumulative rate (%) | 5-y cumulative rate (%) | Hazard ratio (95% CI) | P | |

| Age | ||||

| ≥50 y | 16.8 | 34.0 | 1 | |

| 40–49 y | 23.1 | 40.3 | 1.49 (1.08–2.04) | 0.015 |

| <40 y | 26.6 | 49.6 | 1.85 (1.27–2.71) | 0.001 |

| Race | 0.18 | |||

| Non-Hispanic | 13.8 | 27.6 | 1 | |

| Hispanic | 22.6 | 42.1 | 1.25 (0.90–1.74) | |

| Body mass index | ||||

| <30 kg/m2 | 12.6 | 28.9 | 1 | |

| 30–39.9 kg/m2 | 23.6 | 42.2 | 1.37 (0.97–1.94) | 0.079 |

| ≥40 kg/m2 | 23.4 | 41.2 | 1.07 (0.71–1.62) | 0.74 |

| Diabetes mellitus | ||||

| None | 15.3 | 33.3 | 1 | |

| Preexisting | 24.2 | 39.9 | 1.17 (0.84–1.63) | 0.37 |

| After surgical operation | 39.2 | 62.9 | 2.26 (1.52–3.35) | <0.0001 |

| Hypertension | ||||

| None | 17.2 | 35.6 | 1 | |

| Preexisting | 22.8 | 40.7 | 1.12 (0.81–1.56) | 0.5 |

| After surgical operation | 19.9 | 40.2 | 1.01 (0.61–1.65) | 0.98 |

| Hypercholesterolemia | ||||

| None | 17.5 | 35.2 | 1 | |

| Preexisting | 23.7 | 42.7 | 1.26 (0.89–1.77) | 0.19 |

| After surgical operation | 34.3 | 55.0 | 1.71 (1.12–2.63) | 0.014 |

| Estrogen therapy | 0.66 | |||

| No | 20.1 | 38.6 | 1 | |

| Yes | 20.7 | 20.7 | 0.77 (0.24–2.49) | |

| Disease type | 0.36 | |||

| Hyperplasia | 21.0 | 34.8 | 1 | |

| Cancer | 19.7 | 39.3 | 0.82 (0.53–1.26) | |

| Bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy | 0.047 | |||

| No | 15.9 | 35.0 | 1 | |

| Yes | 20.9 | 40 | 1.70 (1.01–2.86) | |

Multivariate analysis with Cox proportional hazards regression test for P values. All covariates entered into the final model were chosen and grouped based on clinical significance for nonalcoholic fatty liver disease.

FIG. 2.

Effects of oophorectomy on nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Black line, oophorectomy cases; gray line, nonoophorectomy cases. Cumulative proportional risk of fatty liver disease after surgical operation for endometrial cancer or endometrial hyperplasia: (A) age younger than 40 years, (B) age 40 to 49 years, and (C) age 50 years or older. BSO, bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy.

DISCUSSION

The incidence of endometrial cancer in the United States has been rising in recent years probably because of an increase in the obese population.16–18 This trend of obesity includes young women, and a large number of women with endometrial cancer are premenopausal.4 As a consequence, surgical menopause caused by treatment of endometrial cancer is an important consideration to address. The role of oophorectomy in premenopausal women with endometrial cancer needs to be thoughtfully examined—balancing oncologic therapeutic aspects and general health considerations. In general, oophorectomy is performed as part of metastatic evaluation and for hormonal castration based on the rational that most cases of endometrial cancer are estrogen-dependent.3 However, data from recent population-based studies suggested that ovarian preservation may be safe and is not associated with increased endometrial cancer—related mortality in selected women with early-stage disease and low-grade tumors.19,20 In our study, women younger than 40 years demonstrated the highest risk of developing NAFLD and increased risks of multiple medical comorbidities after oophorectomy. Therefore, the risks and benefits of ovarian preservation in young premenopausal women with early-stage low-grade endometrial cancer need to be further studied in a prospective manner.

Our results showed that NAFLD was significantly associated with diabetes mellitus and hypercholesterolemia. Clinically, these findings partly support a recent population-based study, which demonstrated that cardiovascular disease, instead of endometrial cancer progression, is the leading cause of death in women with endometrial cancer.21 This trend was more prominent among women with endometrial cancer who had early-stage disease and low-grade tumor 5 years after surgical operation.21 Estrogen plays an important role in lipid metabolism and insulin resistance by suppressing fat accumulation in the liver, which further prevents insulin resistance, NAFLD, and diabetes mellitus.22,23 Thus, loss of estrogen regulation after oophorectomy in young women with endometrial cancer increases lipid accumulation in the liver, which predisposes to diabetes. In this setting, ET after surgical staging for endometrial cancer may be an option for preventing NAFLD-related metabolic syndrome.24 However, our study had only a small number of women who received ET, making it difficult to draw any conclusions. In a preclinical study using a female mouse model, ET after oophorectomy reduced hepatic fat accumulation and promoted insulin action.24 Because ET among women with endometrial cancer remains controversial,25,26 examining the risks and benefits of ET on a selected group of young women with endometrial cancer merits further investigations for managing not only estrogen withdrawal symptoms but also cardiovascular risk. In addition, testosterone may play a role in the pathogenesis of NAFLD. In a preclinical model, testosterone was reported to ameliorate NAFLD development.27 Therefore, not only estrogen (which decreases fatty acid synthesis) but also testosterone (which decreases fat accumulation and cholesterol synthesis) may be potentially important for regulating NAFLD development.28 In this participant population, younger women who had a higher risk of developing NAFLD were found to be significantly more obese. Although BMI was controlled for, certain factors (such as visceral adiposity and increased body fat percentage) may correlate with a higher risk of NAFLD.

Generally, the effects of estrogen deprivation after oophorectomy are greater in younger women than in older age groups. Therefore, we could hypothesize that the effects of oophorectomy on NAFLD development are greater in young women than in older women. Based on our results, oophorectomy had a great effect on NAFLD development soon after surgical operation among women younger than 40 years; however, observed changes diminished across time (Fig. 2A). Conversely, the effects of oophorectomy on NAFLD development at age 40 to 49 years remained significant across time (Fig. 2B). This is probably caused by differences in group characteristics. Specifically, women younger than 40 years had significantly higher BMI compared with women aged 40 to 49 years (mean BMI, 40.2 vs 34.5 kg/ m2). Excess adiposity is known to be a source of estrogen, and this might be associated with the protective effect of NAFLD development on women younger than 40 years. In addition, because excess adiposity increases the risk of insulin resistance and metabolic syndrome, which are associated with NAFLD, marked obesity predisposes to a high risk of developing NAFLD—even without oophorectomy—among women younger than 40 years. Collectively, weight reduction to prevent metabolic syndrome is paramount in the younger age group.

A potential weakness of this study is its retrospective design, which may miss possible confounding factors. For instance, the exact indications for ovarian preservation were not available in medical records. In addition, in our study, the proportion of women who received ET after surgical operation was very low; therefore, the effects of ET on NAFLD prevention were unclear. Another limitation of this study is a lack of objective measurement of serum estrogen levels at the time of oophorectomy, which would support the study concept of estrogen deprivation and development of NAFLD. A lack of more precise measures of body composition, especially visceral adiposity, also prevents this study from examining the relationship between visceral adiposity and NAFLD and the role of ovarian hormone loss in increasing visceral adiposity. Finally, our study population was predominantly Hispanic, and our findings may not be generalizable to different populations.

CONCLUSIONS

Biological age at oophorectomy significantly impacts the development of NAFLD after surgical treatment of endometrial cancer, and younger age is associated with a higher risk of developing NAFLD. Characterization of obesity in younger women undergoing oophorectomy warrants further investigation. Because NAFLD is associated with the development of diabetes mellitus and hypercholesterolemia (conditions that may increase the risk of cardiovascular events across a long-term period), this information would be beneficial for properly counseling women with endometrial cancer regarding surgical staging.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Financial disclosure/conflicts of interest: None reported.

Supplemental digital content is available for this article. Direct URL citations appear in the printed text and are provided in the HTML and PDF versions of this article on the journal's Website (www.menopause.org).

REFERENCES

- 1.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2015. CA Cancer J Clin 2015;65:5–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wright JD, Barrena Medel NI, Sehouli J, Fujiwara K, Herzog TJ. Contemporary management of endometrial cancer. Lancet 2012;379: 1352–1360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Setiawan VW, Yang HP, Pike MC, et al. Type I and II endometrial cancers: have they different risk factors? J Clin Oncol 2013;31:2607–2618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wright JD. Take 'em or leave 'em: management of the ovaries in young women with endometrial cancer. Gynecol Oncol 2013;131:287–288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Clegg DJ. Minireview: the year in review of estrogen regulation of metabolism. Mol Endocrinol 2012;26:1957–1960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Clark JM. The epidemiology of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in adults. J Clin Gastroenterol 2006;40(suppl 1):S5–S10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brunt EM. Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Semin Liver Dis 2004;24:3–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bohinc BN, Diehl AM. Mechanisms of disease progression in NASH: new paradigms. Clin Liver Dis 2012;16:549–565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lomonaco R, Sunny NE, Bril F, Cusi K. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: current issues and novel treatment approaches. Drugs 2013;73:1–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Matsuo K, Yessaian AA, Lin YG, et al. Predictive model of venous thromboembolism in endometrial cancer. Gynecol Oncol 2013;128:544–551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Matsuo K, Gray MJ, Yang DY, et al. The endoplasmic reticulum stress marker, glucose-regulated protein-78 (GRP78) in visceral adipocytes predicts endometrial cancer progression and patient survival. Gynecol Oncol 2013;128:552–559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Matsuo K, Cahoon SS, Gualtieri M, et al. Significance of adenomyosis on tumor progression and survival outcome of endometrial cancer. Ann Surg Oncol 2014;21:4246–4255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Matsuo K, Opper NR, Ciccone MA, et al. Time interval between endometrial biopsy and surgical staging for type I endometrial cancer: association between tumor characteristics and survival outcome. Obstet Gynecol 2015;125:424–433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pecorelli S. Revised FIGO staging for carcinoma of the vulva, cervix, and endometrium. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2009;105:103–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Castera L, Vilgrain V, Angulo P. Noninvasive evaluation of NAFLD. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2013;10:666–675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Vital signs: state-specific obesity prevalence among adults—United States, 2009. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2010;59:951–955. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Riley LW, Raphael E, Faerstein E. Obesity in the United States—dysbiosis from exposure to low-dose antibiotics? Front Public Health 2013;1:69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schmandt RE, Iglesias DA, Co NN, Lu KH. Understanding obesity and endometrial cancer risk: opportunities for prevention. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2011;205:518–525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wright JD, Buck AM, Shah M, Burke WM, Schiff PB, Herzog TJ. Safety of ovarian preservation in premenopausal women with endometrial cancer. J Clin Oncol 2009;27:1214–1219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lee TS, Lee JY, Kim JW, et al. Outcomes of ovarian preservation in a cohort of premenopausal women with early-stage endometrial cancer: a Korean Gynecologic Oncology Group study. Gynecol Oncol 2013;131:289–293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ward KK, Shah NR, Saenz CC, McHale MT, Alvarez EA, Plaxe SC. Cardiovascular disease is the leading cause of death among endometrial cancer patients. Gynecol Oncol 2012;126:176–179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lemieux S, Prud'homme D, Bouchard C, Tremblay A, Desprès JP. Sex differences in the relation of visceral adipose tissue accumulation to total body fatness. Am J Clin Nutr 1993;58:463–467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Riant E, Waget A, Cogo H, Arnal JF, Burcelin R, Gourdy P. Estrogens protect against high-fat diet—induced insulin resistance and glucose intolerance in mice. Endocrinology 2009;150:2109–2117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhu L, Brown WC, Cai Q, et al. Estrogen treatment after ovariectomy protects against fatty liver and may improve pathway-selective insulin resistance. Diabetes 2013;62:424–434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Manley K, Edey K, Braybrooke J, Murdoch J. Hormone replacement therapy after endometrial cancer. Menopause Int 2012;18:134–138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Barakat RR, Bundy BN, Spirtos NM, Bell J, Mannel RS. Gynecologic Oncology Group Study. Randomized double-blind trial of estrogen replacement therapy versus placebo in stage I or II endometrial cancer: a Gynecologic Oncology Group Study. J Clin Oncol 2006;24:587–592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nikolaenko L, Jia Y, Wang C, et al. Testosterone replacement ameliorates nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in castrated male rats. Endocrinology 2014;155:417–428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhang H, Liu Y, Wang L, et al. Differential effects of estrogen/androgen on the prevention of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in the male rat. J Lipid Res 2013;54:345–357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.