Abstract

Context

Lower dehydroepiandrosterone-sulfate (DHEA-S) levels have been inconsistently associated with coronary heart disease (CHD) and mortality. Data are limited for heart failure (HF) and association between DHEA-S change and events.

Objective

Assess associations between low DHEA-S/DHEA-S change and incident HF hospitalization, CHD, and mortality in older adults.

Design

DHEA-S was measured in stored plasma from visits 4 (1996-1998) and 5 (2011-2013) of the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities study. Follow-up for incident events: 18 years for DHEA-S level; 5.5 years for DHEA-S change.

Setting

General community.

Participants

Individuals without prevalent cardiovascular disease (n = 8143, mean age 63 years).

Main Outcome Measure

Associations between DHEA-S and incident HF hospitalization, CHD, or mortality; associations between 15-year change in DHEA-S (n = 3706) and cardiovascular events.

Results

DHEA-S below the 15th sex-specific percentile of the study population (men: 55.4 µg/dL; women: 27.4 µg/dL) was associated with increased HF hospitalization (men: hazard ratio [HR] 1.30, 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.07-1.58; women: HR 1.42, 95% CI, 1.13-1.79); DHEA-S below the 25th sex-specific percentile (men: 70.0 µg/dL; women: 37.1 µg/dL) was associated with increased death (men: HR 1.12, 95% CI, 1.01-1.25; women: HR 1.19, 95% CI, 1.03-1.37). In men, but not women, greater percentage decrease in DHEA-S was associated with increased HF hospitalization (HR 1.94, 95% CI, 1.11-3.39). Low DHEA-S and change in DHEA-S were not associated with incident CHD.

Conclusions

Low DHEA-S is associated with increased risk for HF and mortality but not CHD. Further investigation is warranted to evaluate mechanisms underlying these associations.

Keywords: DHEA-S, heart failure, mortality, aging

Dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) is a steroid hormone predominantly synthesized in the adrenal cortex. Derived from cholesterol, DHEA shares common early precursors with mineralocorticoids and glucocorticoids and is itself an intermediary of the sex hormones estradiol and testosterone. In the circulation, DHEA is found predominantly in the sulfate ester form (DHEA-S) and is the most abundant steroid hormone (1). It is well established that serum DHEA/DHEA-S levels decrease with age (2-4). Meanwhile, lower levels of DHEA/DHEA-S have been associated with coronary heart disease (CHD) and mortality in older men and women, though results are inconsistent (5-9).

The tissue effects of DHEA/DHEA-S on the cardiovascular system and other tissues are most likely due to the peripheral conversion in target tissues to estrogens and testosterone (10). Proposed direct cardioprotective properties of DHEA are based on in vitro and animal studies, and include favorable effects on endothelial function, vascular remodeling, and inflammation (11, 12). However, these effects have not yet been confirmed. Lower levels of endogenous DHEA/DHEA-S have been associated with greater progression of coronary and aortic atherosclerosis and with carotid intimal–medial thickness (13-15). Previous randomized controlled trials of DHEA supplementation have failed to show consistent results with respect to clinical benefits (16-19).

Although a large volume of epidemiological data describes the general association of DHEA-S in older adults with CHD and mortality, especially in men, fewer data are available on the relationship between DHEA-S and heart failure (HF) (9). Information on how change in DHEA-S is associated with heart disease and mortality risk is also limited. Moreover, mechanisms by which DHEA/DHEA-S is associated with heart disease in older adults is poorly understood. The Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) study, with DHEA-S measurements at 2 time points in older adults and rigorous adjudication of clinical events, provided the opportunity to address these topics. Finally, we leveraged the robust proteomics dataset from ARIC to explore potential biological pathways of how DHEA-S levels relate to aging and heart disease.

Methods

Study population

The ARIC study is a prospective population study of subclinical and clinical cardiovascular disease (CVD) in adults who were middle-aged (aged 45-64 years) when they were recruited from 4 US communities at the first visit in 1987 through 1989 (20). The study protocol was approved by the institutional review boards of all participating centers, and all participants provided written informed consent. This analysis used data from ARIC visits 4 (1996-1998) and 5 (2011-2013).

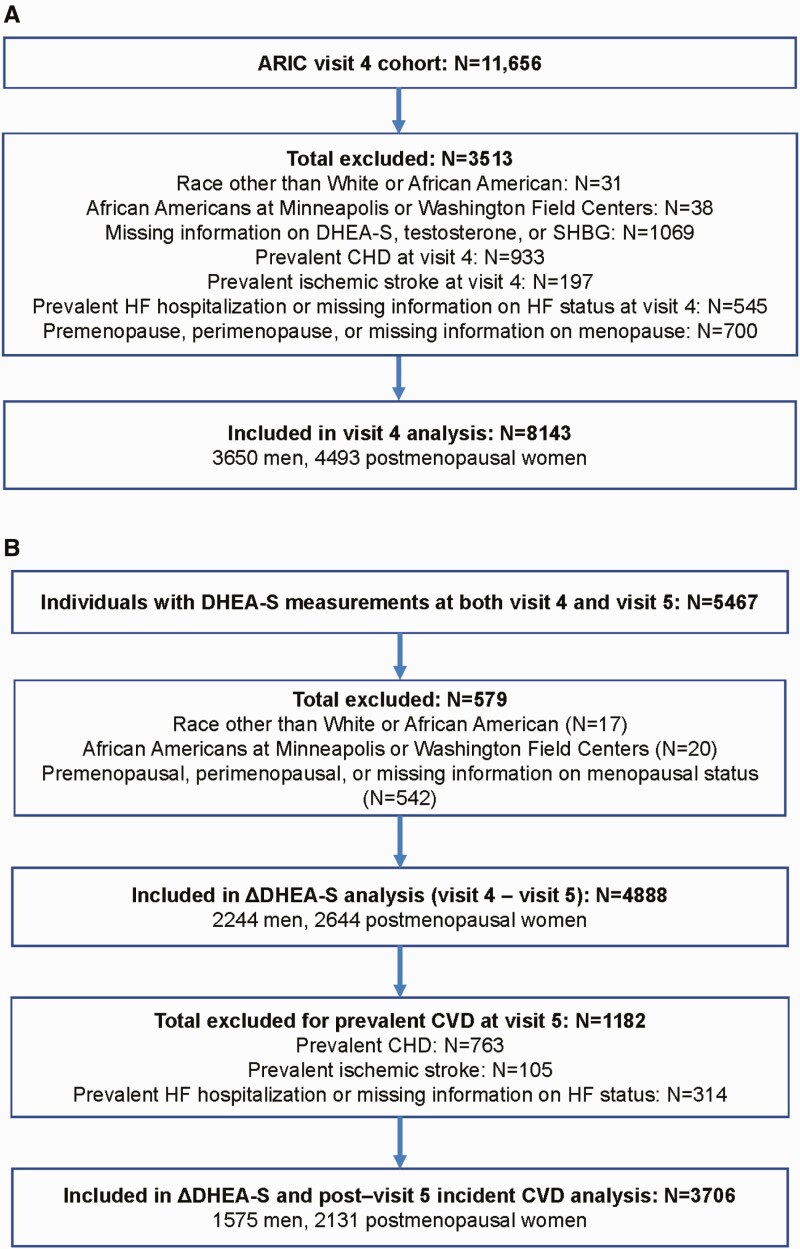

As we wanted to assess whether DHEA-S was associated with cardiac events and death independent of sex hormones, we excluded participants without DHEA-S, testosterone, or sex hormone -binding globulin (SHBG) measurements. We also excluded participants of race other than white or African American and nonwhite participants at the Minneapolis and Washington County centers because of small numbers, and participants with prevalent CHD, stroke, or HF at the analyses-specific index visit. Prevalent CHD and stroke were defined as self-reported myocardial infarction (MI) or stroke before visit 1 or ARIC-adjudicated MI, silent MI (diagnosed by electrocardiogram changes), coronary revascularization, or stroke between visits 1 and 4 or 5 (index visit) (21). Prevalent HF was defined as signs and symptoms of HF by the Gothenburg criteria at visit 1 or HF hospitalization as determined by diagnosis code (International Classification of Diseases, 9th edition [ICD-9] code 428) between ARIC visits 1 and 4 or 5 (index visit). We further excluded participants who were premenopausal or perimenopausal, defined as having had a menstrual period within 2 years before the visit, and those missing information on menopausal status at visit 4. After exclusions, 8143 participants (3650 men and 4493 women) at visit 4 (Fig. 1a) and 3706 individuals (1575 men and 2131 women) at visit 5 (Fig. 1b) were included in this analysis.

Figure 1.

Study cohort at Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) (a) visit 4 and for the (b) analysis of change in DHEA-S between ARIC visit 4 and visit 5.

Hormone quantification

DHEA-S levels were quantified in stored plasma samples from ARIC visits 4 and 5 using methods described previously (22). Endogenous DHEA-S was measured during 2015 and 2016 in EDTA plasma samples (collected in 1996-1998 at ARIC visit 4 and 2011-2013 at ARIC visit 5; stored at –70°C) using chemiluminescent microparticle immunoassay on the Architect i2000sr instrument (Abbott Laboratories, Abbott Park, IL). Approximately 396 plasma samples were split at the time of blood draw and then were processed, stored, and analyzed separately as blind duplicates. After removal of outlier pairs (difference >3 standard deviations from the mean), interassay reliability was good for DHEA-S (coefficient of variation 6.9%; Pearson’s r = 0.99; 8 pairs removed). Interassay coefficients of variation for control levels with mean DHEA-S concentrations of 10.3 µg/dL, 100.3 µg/dL, and 997.4 µg/dL were 7.3%, 4.1%, and 3.3%, respectively.

Total testosterone and SHBG were measured in the same plasma samples from visits 4 and 5 as the DHEA-S using chemiluminescent microparticle immunoassays on the Architect i2000sr instrument (Abbott Laboratories). After removal of outlier pairs (difference >3 standard deviations from the mean), interassay reliability was good for testosterone (coefficient of variation 9.3%; Pearson’s r = 0.99; 11 pairs removed) and SHBG (coefficient of variation 15.0%; Pearson’s r = 0.96; 8 pairs removed). Interassay coefficients of variation for control levels with mean testosterone concentrations of 9.9 ng/dL, 75.2 ng/dL, and 246.5 ng/dL were 8.9%, 6.6%, and 5.5%, respectively. Interassay coefficients of variation for control levels with mean SHBG concentrations of 8.8 nmol/L, 23.8 nmol/L, and 143.0 nmol/L were 6.9%, 8.0%, and 6.3%, respectively.

Covariates

Covariates included age, race, total cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C), systolic blood pressure (SBP), use of antihypertensive medication, use of lipid-lowering medication, smoking status, diabetes status, body mass index (BMI), estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR), and hormonal therapy use (women only, available only at visit 4). Medical history, demographic data, anthropometric data, blood pressure, and lipid measurements were obtained at ARIC visit 4 or visit 5 depending on the index visit used. We included hormonal therapy as a covariate only for visit 4 analyses. Protocols for assessing lipids and blood pressure have been described previously (23, 24). Diabetes was defined as self-reported diabetes diagnosed by a physician, use of hypoglycemic medications, nonfasting serum glucose levels ≥200 mg/dL, or fasting serum glucose level ≥126 mg/dL. eGFR was based on the creatinine-based Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration equation (25).

Outcome measures

For the prospective analysis, the primary outcomes were after visit 4 or after visit 5 incident HF hospitalization, CHD, or all-cause death. Definitions and methods of assessing incident HF hospitalization in the ARIC study have been previously described (26). HF hospitalization was determined by diagnostic code (ICD-9 code 428) from hospital discharges until 2004 and by additional adjudication by an expert panel after 2004. Incident CHD events included fatal CHD, definite or probable MI, silent MI (as determined by ARIC examination electrocardiogram), and coronary revascularization (27). Deaths were ascertained through review of hospital discharge records and death certificates, supplemented by informant interviews or physician questionnaires for out-of-hospital deaths. We assessed all-cause death and cardiovascular death in our analyses. Deaths were classified as CVD-related based on diagnostic codes (ICD-9 codes 390-459 or ICD “I” codes) (28). Of note, we focused primarily on cardiac outcomes and did not include incident stroke because of potential differences in patterns of relationships between each outcome and between sexes, which would make discussion in a single manuscript difficult.

We further performed analyses to assess associations between DHEA-S and markers of subclinical myocardial injury, which have in turn been associated with incident HF. Subclinical myocardial injury was evaluated based on levels (at visits 4 and 5) of N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP) and high-sensitivity troponin T (hs-TnT) (29, 30).

Statistical analysis

All analyses were performed separately for men and women. In analyses evaluating the association of DHEA-S level with incident HF, CHD, and death, we used ARIC visit 4 as the index visit. For analyses involving the association between change in DHEA-S level over time with incident events, we used ARIC visit 5 as the index visit.

For prospective analysis assessing the association between DHEA-S and incident cardiac events or deaths, Cox regression models were used to estimate the hazard ratios (HRs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). We first assessed the shape of the association between DHEA-S and outcome variables using Cox models with DHEA-S modeled as restricted cubic splines. The knots were placed at the 5th, 27.5th, 50th, 72.5th, and 95th percentiles, and we adjusted for age and race. Because the analysis suggested a nonlinear association between DHEA-S and outcomes in both men and women, we performed analysis to determine whether low DHEA-S levels may be associated with increased risk for HF hospitalization, CHD, and all-cause death. Because there is not a well-established clinical cutpoint for low DHEA-S levels, we evaluated the lowest 25th, 15th, and 10th percentiles of DHEA-S level in men and women. Cox regression analysis was used to evaluate the association between DHEA-S level (greater than or equal to vs less than these sex-specific cutpoints) and outcome measures of incident CHD, HF hospitalization, and all-cause mortality. Model 1 was adjusted for age and race. Model 2 was adjusted for model 1 plus total cholesterol, HDL-C, SBP, use of antihypertensive medication, smoking status, diabetic status, BMI, use of lipid-lowering medication, eGFR, log-testosterone, and log-SHBG; for visit 4 analyses only in women, we also included current hormonal therapy use in model 2 adjustments (hormonal therapy data were not available at visit 5). Additional adjustment was performed to include NT-proBNP (model 3 = model 2 plus NT-proBNP). In primary survival analyses, individuals who died of causes other than CVD were assumed to still be at risk of developing CVD. To address this assumption, we performed a sensitivity analysis using the Fine and Gray approach to competing risks (31).

To determine characteristics at visit 4 associated with change in DHEA-S levels between visits 4 and 5, individuals were categorized into quartiles of absolute change and percent change in DHEA-S concentrations from visit 4 to visit 5 (2244 men and 2644 women). Multinomial logistic regression was then used to assess covariables at visit 4 that were associated with the absolute change (and percent change) in DHEA-S from visit 4 to visit 5. Next, the associations of percent change in DHEA-S between visits 4 and 5 with cardiac events and death, in individuals free of incident CVD at visit 5 (1575 men and 2131 women), was assessed using Cox regression models as described previously.

Finally, we assessed the association between DHEA-S and evidence of subclinical cardiac disease in individuals without prevalent CVD. We performed cross-sectional analyses of associations of DHEA-S with biomarkers (hs-TnT and NT-proBNP) measured at visits 4 and at 5. Linear regression models were used with DHEA-S modeled as a dichotomous variable (at or above vs below the sex-specific cutpoint) and biomarkers (log-transformed hs-TnT or NT-proBNP levels) treated as continuous variables. Regression models were adjusted for model 2 covariables (see previous section). STATA version 12 (StataCorp, College Station, TX) and SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC) were used for the statistical analyses.

Analysis of plasma proteins and pathways associated with DHEA-S

To understand better the biological pathways by which DHEA-S may be associated with CVD, we performed exploratory analyses using proteomics data from ARIC visit 5. Plasma proteins were measured using the SomaLogic v4 aptamer platform (4877 proteins). From the study population, participants with SomaLogic aptamer measurements were included in these analyses (n = 3728). Detailed methods of the SomaLogic assay have been described elsewhere (32).

We performed cross-sectional analysis of plasma proteins measured in the SomaLogic proteomics assay and DHEA-S levels at visit 5. Proteins (as measured by SomaLogic assay) were identified that were significantly associated with DHEA-S level based on P values for the β coefficient from linear regression analysis with model 2 (see previous section) adjustment. P values were corrected for multiple testing using the Benjamini–Hochberg false discovery rate procedure. A false discovery rate P < 0.05 was set as a threshold for statistical significance. We used Ingenuity Pathway Analysis (IPA) (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany; https://www.qiagenbioinformatics.com/products/ingenuity-pathway-analysis), a bioinformatics platform for analysis of omics data, to probe for potential biological mechanisms that associate plasma proteins/corresponding genes with DHEA-S. The proteins found to be significantly associated with DHEA-S were uploaded and linked to corresponding genes in the IPA database. We ran IPA analyses using all proteins in the Ingenuity Knowledge Base as a background/reference to account for possible selection biases of proteins used in the aptamer assay. IPA Core Analysis was performed to identify pertinent canonical pathways associated with DHEA-S level. This analysis involves the use of Fisher’s exact tests to quantify the probability that the commonality between proteins identified from the input dataset and a canonical pathway was due to random chance alone. We further performed IPA network analysis to evaluate for significant biological networks, interactions both directly and indirectly through mediator genes or gene products, among proteins identified to be significantly associated with DHEA-S. A detailed description of the statistical methodology used in the IPA Core Analyses and IPA Network Analysis has been previously published (33, 34).

Results

Association between DHEA-S level and covariates

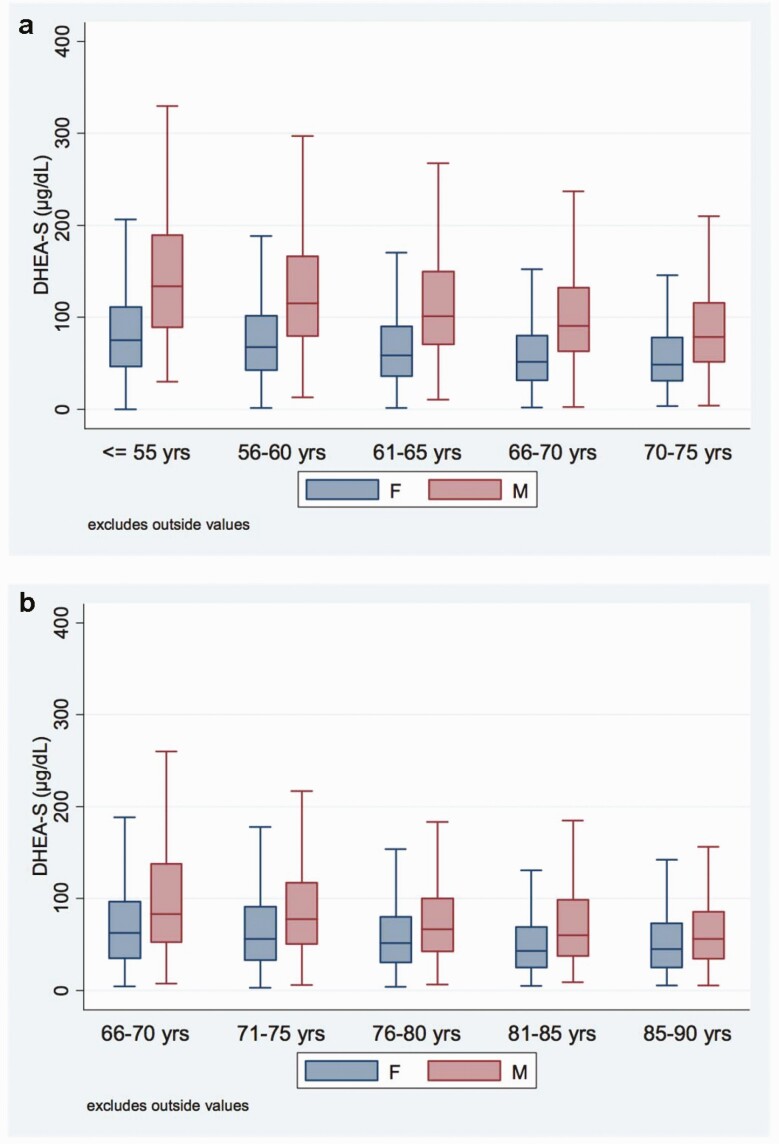

At visits 4 and 5, mean age was 62.8 ± 5.7 and 74.5 ± 5.1 years in men and 63.1 ± 5.5 and 75.3 ± 5.2 years in women. At visits 4 and 5, the median (25th, 75th percentile) DHEA-S level was 103.0 µg/dL (69.9, 152.0) and 74.5 µg/dL (48.3, 115.4) in men and 59.1 µg/dL (36.1, 92.0) and 54.5 µg/dL (31.7, 88.2) in women. The 5th and 95th, 10th and 90th, and 15th and 85th percentile ranges of DHEA-S concentration at visits 4 and 5 for men and women are reported in Table 1. The distribution of DHEA-S level across age categories for men and women is shown in Fig. 2. Overall, circulating levels of DHEA-S were higher in men than in women, but DHEA-S levels also decreased more with age in men than in women.

Table 1.

Dehydroepiandrosterone-sulfate Distribution in Men and Postmenopausal Women

| Dehydroepiandrosterone-sulfate (µg/dL) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| 5th, 95th Percentile | 10th, 90th Percentile | 15th, 85th Percentile | |

| Men | |||

| Visit 4 | 35.4, 258.2 | 46.7, 217.2 | 55.4, 187.1 |

| Visit 5 | 22.1, 215.6 | 29.0, 166.1 | 34.6, 142.8 |

| Women | |||

| Visit 4 | 15.5, 163.2 | 21.9, 131.9 | 27.3, 114.4 |

| Visit 5 | 12.6, 155.5 | 18.2, 123.6 | 22.2, 106.7 |

Figure 2.

Distribution of circulating dehydroepiandrosterone-sulfate (DHEA-S) (µg/dL) concentrations in men and postmenopausal women by age groups at Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) (a) visit 4 and (b) visit 5.

In men, lower DHEA-S levels were associated with higher age, BMI, triglycerides, SHBG, and rates of antihypertensive and lipid-lowering medication use at visit 4. A lower percentage of African American men had DHEA-S level in the lower ranges. Lower DHEA-S levels were also associated with lower total cholesterol, HDL-C, eGFR, and rates of current smoking (Table 2). In women, lower DHEA-S levels were associated with higher age, SBP, HDL-C, triglycerides, SHBG, and rates of antihypertensive medication, lipid-lowering medication, and hormonal therapy use at visit 4. As in men, a lower percentage of African American women had DHEA-S levels in the lower ranges. Lower DHEA-S levels were further associated with a lower percentage of women with diabetes and with lower BMI, fasting glucose, eGFR, testosterone, and rates of current smoking at visit 4 (Table 3).

Table 2.

Basic characteristics at visit 4 across DHEA-S quartiles in men

| DHEA-S Quartiles (µg/dL) | P Trend | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Q1 (2.7-69.9) (N = 915) | Q2 (70.0-103.0) (N = 912) | Q3 (103.2-152.0) (N = 911) | Q4 (152.1-632.7) (N = 912) | ||

| Age (y) (N = 3650) | 64.8 ± 5.58 | 63.2 ± 5.53 | 62.3 ± 5.52 | 61.0 ± 5.38 | <0.001 |

| African Americans (%) (N = 3650) | 14.43 | 17.00 | 19.32 | 21.38 | <0.001 |

| BMI (kg/m2) (N = 3642) | 28.5 ± 4.64 (N = 913) | 28.4 ± 4.39 (N = 911) | 28.4 ± 4.29 (N = 907) | 28.0 ± 4.37 (N = 911) | 0.014 |

| SBP (mm Hg) (N = 3649) | 127.3 ± 18.47 (N = 915) | 125.4 ± 16.92 (N = 911) | 126.1 ± 17.33 (N = 911) | 126.2 ± 17.84 (N = 912) | 0.271 |

| DBP (mm Hg) (N = 3649) | 72.0 ± 10.17 (N = 915) | 71.9 ± 9.38 (N = 911) | 72.8 ± 10.01 (N = 911) | 73.5 ± 10.03 (N = 912) | <0.001 |

| Fasting glucose (mg/dL) (N = 3492) | 109.1 ± 28.15 (N = 874) | 108.7 ± 27.48 (N = 870) | 109.0 ± 30.06 (N = 874) | 110.4 ± 33.32 (N = 874) | 0.975 |

| Total cholesterol (mg/dL) (N = 3650) | 191.3 ± 34.44 | 192.6 ± 33.61 | 191.5 ± 32.73 | 195.9 ± 35.12 | 0.007 |

| HDL-C (mg/dL) (N = 3650) | 43.1 ± 13.07 | 42.2 ± 13.23 | 43.5 ± 13.54 | 45.3 ± 14.91 | <0.001 |

| Triglycerides (mg/dL) (N = 3650) | 122 (88, 172) | 125 (87, 177) | 117 (84, 166) | 117 (83, 163) | 0.007 |

| Antihypertensive medication use (%) (N = 3650) | 40.77 | 36.18 | 34.80 | 32.79 | <0.001 |

| Lipid-lowering medication use (%) (N = 3641) | 13.11 (N = 915) | 12.32 (N = 909) | 9.91 (N = 908) | 8.80 (N = 909) | 0.001 |

| Diabetes (%) (N = 3626) | 17.82 (N = 909) | 15.38 (N = 904) | 15.38 (N = 904) | 14.96 (N = 909) | 0.113 |

| Current smoking (%) (N = 3625) | 11.23 (N = 908) | 12.57 (N = 907) | 16.09 (N = 901) | 19.80 (N = 909) | <0.001 |

| PCE score (N = 3615) | 15.9 (10.4, 24.2) (N = 906) | 14.2 (8.9, 21.0) (N = 903) | 13.2 (8.5, 20.2) (N = 899) | 12.2 (8.0, 18.1) (N = 907) | <0.001 |

| eGFR (mL/min/1.73 m2) (N = 3650) | 84.8 ± 14.02 | 84.8 ± 14.82 | 86.3 ± 15.33 | 87.8 ± 14.23 | <0.001 |

| hs-CRP (mg/L) (N = 3599) | 1.64 (0.84, 3.54) (N = 902) | 1.68 (0.87, 3.33) (N = 896) | 1.65 (0.91, 3.54) (N = 900) | 1.66 (0.84, 3.52) (N = 901) | 0.871 |

| Testosterone (nmol/L) (N = 3650) | 18.02 (13.76, 22.72) | 17.83 (13.75, 23.60) | 18.24 (14.05, 23.42) | 17.70 (13.26, 22.56) | 0.298 |

| SHBG (nmol/L) (N = 3650) | 32.2 (24.0, 42.7) | 32.0 (23.5, 42.0) | 31.0 (22.6, 40.7) | 31.1 (23.0, 41.8) | 0.012 |

Data presented as mean ± SD, median (25th, 75th percentiles), or percentage. P values for linear trends were calculated by using trend test across ordered groups.

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; DHEA-S, dehydroepiandrosterone-sulfate; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; HDL-C, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; hs-CRP, high-sensitivity C-reactive protein; PCE, pooled cohort equation; Q, quartiles; SBP, systolic blood pressure.

Table 3.

Basic Characteristics at Visit 4 Across DHEA-S Quartiles in Postmenopausal Women

| DHEA-S Quartiles (µg/dL) | P Trend | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Q1 (0-37.0) (N = 1155) | Q2 (37.1-60.0) (N = 1141) | Q3 (60.1-93.5) (N = 1111) | Q4 (93.6-541.3) (N = 1086) | ||

| Age (y) (N = 4493) | 64.5 ± 5.35 | 63.5 ± 5.42 | 62.6 ± 5.40 | 61.8 ± 5.44 | <0.001 |

| African Americans (%) (N = 4493) | 21.65 | 25.24 | 24.57 | 27.26 | 0.005 |

| BMI (kg/m2) (N = 4489) | 28.1 ± 5.82 (N = 1153) | 29.0 ± 6.26 (N = 1141) | 29.0 ± 6.06 (N = 1110) | 29.0 ± 6.30 (N = 1085) | 0.001 |

| SBP (mm Hg) (N = 4493) | 129.0 ± 19.51 | 128.8 ± 20.03 | 126.9 ± 19.47 | 127.5 ± 19.04 | 0.010 |

| DBP (mm Hg) (N = 4493) | 69.8 ± 9.91 | 69.9 ± 10.52 | 69.8 ± 10.35 | 70.5 ± 10.33 | 0.128 |

| Fasting glucose (mg/dL) (N = 4314) | 102.8 ± 26.71 (N = 1111) | 105.3 ± 28.10 (N = 1099) | 105.7 ± 30.85 (N = 1052) | 108.4 ± 35.04 (N = 1052) | <0.001 |

| Total cholesterol (mg/dL) (N = 4492) | 207.2 ± 36.82 (N = 1154) | 207.7 ± 36.24 (N = 1141) | 209.1 ± 36.29 (N = 1111) | 208.9 ± 36.03 (N = 1086) | 0.077 |

| HDL cholesterol (mg/dL) (N = 4492) | 57.4 ± 17.16 (N = 1154) | 55.4 ± 15.95 (N = 1141) | 55.5 ± 16.92 (N = 1111) | 55.9 ± 16.22 (N = 1086) | 0.029 |

| Triglycerides (mg/dL) (N = 4492) | 129 (91, 184) (N = 1154) | 121 (90, 175) (N = 1141) | 120 (87, 171) (N = 1111) | 115 (86, 163) (N = 1086) | <0.001 |

| Antihypertensive medication use (%) (N = 4493) | 44.24 | 41.98 | 35.10 | 39.96 | 0.002 |

| Lipid-lowering medication use (%) (N = 4482) | 14.99 (N = 1154) | 13.95 (N = 1140) | 10.05 (N = 1105) | 7.20 (N = 1083) | <0.001 |

| Diabetes (%) (N = 4479) | 13.01 (N = 1153) | 14.26 (N = 1136) | 13.99 (N = 1108) | 16.45 (N = 1082) | 0.033 |

| Current smoking (%) (N = 4476) | 9.80 (N = 1153) | 13.13 (N = 1135) | 14.53 (N = 1108) | 18.15 (N = 1080) | <0.001 |

| PCE score (N = 4474) | 8.0 (4.4, 13.0) (N = 1152) | 7.5 (4.1, 12.9) (N = 1135) | 6.2 (3.3, 11.9) (N = 1107) | 6.3 (3.3, 11.7) (N = 1080) | <0.001 |

| eGFR (mL/min/1.73 m2) (N = 4492) | 85.8 ± 16.15 (N = 1154) | 87.0 ± 15.98 (N = 1141) | 87.5 ± 15.64 (N = 1111) | 88.3 ± 15.73 (N = 1086) | <0.001 |

| hs-CRP (mg/L) (N = 4434) | 3.20 (1.33, 6.94) (N = 1138) | 3.03 (1.22, 6.20) (N = 1129) | 2.96 (1.36, 5.72) (N = 1092) | 2.97 (1.27, 6.39) (N = 1075) | 0.355 |

| Testosterone (nmol/L) (N = 4493) | 0.59 (0.47, 0.81) | 0.74 (0.58, 0.99) | 0.84 (0.67, 1.09) | 1.02 (0.83, 1.31) | <0.001 |

| SHBG (nmol/L) (N = 4493) | 50.2 (28.4, 85.7) | 43.0 (26.5, 72.8) | 40.0 (25.1, 71.0) | 37.7 (25.0, 61.5) | <0.001 |

| Hormonal therapy use (%) (N = 2981) | 48.21 (N = 780) | 38.73 (N = 754) | 31.86 (N = 725) | 31.86 (N = 722) | <0.001 |

| Hormone user categories (N = 2981) | |||||

| Current estrogen user (%) | 40.26 | 31.56 | 23.03 | 22.71 | <0.001 |

| Current estrogen and progestin user (%) | 7.95 | 7.16 | 8.83 | 9.14 | |

| Never used hormone (%) | 47.44 | 56.50 | 63.31 | 63.71 | |

| Former hormone user (%) | 4.36 | 4.77 | 4.83 | 4.43 | |

Data presented as mean ± SD, median (25th, 75th percentiles), or percentage. P values for linear trends were calculated by using trend test across ordered groups.

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; DHEA-S, dehydroepiandrosterone-sulfate; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; HDL, high-density lipoprotein; hs-CRP, high sensitivity C-reactive protein; PCE, pooled cohort equation; Q, quartiles; SBP, systolic blood pressure.

DHEA-S level and incident events during long-term follow up

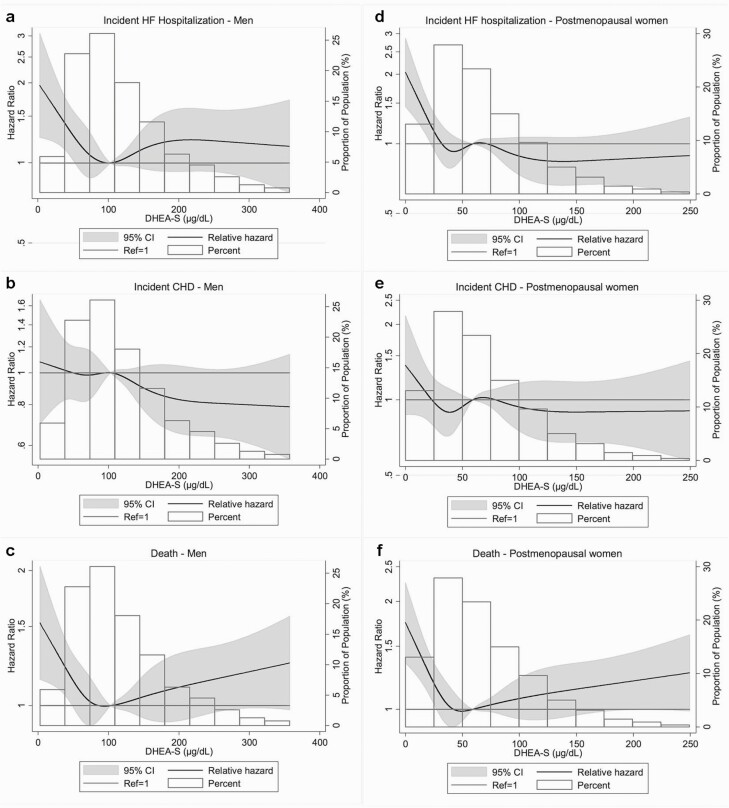

During a median follow-up of ~18 years, 423 incident HF hospitalizations, 710 incident CHD events, and 1031 deaths occurred in men, and 569 incident HF hospitalizations, 454 incident CHD, and 924 deaths occurred in women. In both men and women, spline analyses showed that the highest risk for incident HF hospitalization, CHD, and death was associated with the lowest levels of DHEA-S at visit 4. Associations were nonlinear for most endpoints, with a suggestion of a threshold for HF and death (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Restricted cubic spline showing the association of dehydroepiandrosterone-sulfate (DHEA-S) at Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) visit 4 with incident heart failure (HF) hospitalization, coronary heart disease (CHD), or death in 1996 through 2017. The sex-specific median value of DHEA-S was used as reference in a Cox proportional hazard model adjusted for age and race. The knots were placed at the 5th, 27.5th, 50th, 72.5th, and 95th percentiles. (a-c) Men: The median value of DHEA-S was 103 µg/dL; values for DHEA-S >360 µg/dL were dropped from the analysis (n = 39). (d-f) Postmenopausal women: The median value of DHEA-S was 59 µg/dL; values for DHEA-S >250 µg/dL were dropped from the analysis (n = 39).

In men, DHEA-S levels below the lowest 15th percentile (55.4 µg/dL) were significantly associated with increased risk for incident HF hospitalizations (HR 1.30; 95% CI, 1.07-1.58), whereas DHEA-S levels below the lowest 25th percentile (70.0 µg/dL) were significantly associated with increased risk for all-cause death (HR 1.12; 95% CI, 1.01-1.25) after model 2 adjustment. There was no significant association of DHEA-S with incident CHD and cardiovascular death after adjustment with model 2 variables (Tables 4-7).

Table 4.

Threshold Analyses Assessing the Association Between DHEA-S and Incident HF Hospitalization, CHD, and Death Among Older Men and Women Without Prevalent CVD

| Men | Women | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex-specific Percentile of DHEA-S Level at Visit 4 | ||||||||||||

| 25th (70.0 µg/dL) | 15th (55.4 µg/dL) | 10th (46.7 µg/dL) | 25th (37.1 µg/dL) | 15th (27.4 µg/dL) | 10th (21.9 µg/dL) | |||||||

| ≥ | < | ≥ | < | ≥ | < | ≥ | < | ≥ | < | ≥ | < | |

| HF hospitalization, n/N (%) | 455/2735 (16.6) | 198/915 (21.6) | 514/3103 (16.6) | 139/547 (25.4) | 563/3286 (17.1) | 90/364 (24.7) | 592/3338 (17.74) | 259/1155 (22.42) | 683/3817 (17.89) | 168/676 (24.85) | 730/4042 (18.06) | 121/451 (26.83) |

| HR (95% CI) | 1.16 (0.97–1.37) | 1.30 (1.07–1.58) | 1.21 (0.97–1.53) | 1.12 (0.91–1.38) | 1.42 (1.13–1.79) | 1.54 (1.17–2.03) | ||||||

| CHD, n/N (%) | 608/2735 (22.2) | 228/915 (24.9) | 692/3103 (22.3) | 144/547 (26.3) | 748/3286 (22.8) | 88/364 (24.2) | 416/3338 (12.46) | 152/1155 (13.16) | 473/3817 (12.39) | 95/676 (14.05) | 496/4042 (12.27) | 72/451 (15.96) |

| HR (95% CI) | 1.08 (0.92–1.26) | 1.10 (0.91–1.32) | 1.00 (0.80–1.25) | 0.98 (0.76–1.27) | 1.11 (0.82–1.50) | 1.40 (0.99–1.98) | ||||||

| All-cause death, n/N (%) | 1118/2735 (40.9) | 498/915 (54.4) | 1310/3103 (42.2) | 306/547 (55.9) | 1402/3286 (42.7) | 214/364 (58.8) | 1126/3338 (33.73) | 500/1155 (43.29) | 1316/3817 (34.48) | 310/676 (45.86) | 1420/4042 (35.13) | 206/451 (45.68) |

| HR (95% CI) | 1.12 (1.01–1.25) | 1.07 (0.94–1.22) | 1.08 (0.93–1.26) | 1.19 (1.03–1.37) | 1.23 (1.04–1.45) | 1.21 (0.99–1.47) | ||||||

Follow-up from visit date of ARIC visit 4 to December 31, 2017. Cox regression models were used to calculate hazard ratio (HR) (95% confidence interval [CI]); bolded values indicate statistical significance. DHEA-S at or above the threshold (reference) was compared with DHEA-S below the threshold. Adjustment for age, race, total cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, systolic blood pressure, antihypertensive medication use, current smoking, diabetes status, body mass index, lipid-lowering medication use, estimated glomerular filtration rate, log-testosterone, log-SHBG, and hormonal therapy use (women only).

Abbreviations: CHD, coronary heart disease; DHEA-S, dehydroepiandrosterone-sulfate; HF, heart failure.

Table 7.

Association of Post–Visit 4 Incident CVD and DHEA-S (at or Above vs Below 10th Percentile for DHEA-S) in Men

| DHEA-S (µg/dL) | P Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 46.7-632.7 | 2.7-46.6 | ||

| Incident CHD | |||

| n/N (%) | 748/3286 (22.76) | 88/364 (24.18) | 0.543 |

| Model 1, HR (95% CI) | Reference | 0.99 (0.79-1.24) | 0.951 |

| Model 2, HR (95% CI) | Reference | 1.00 (0.80-1.25) | 0.981 |

| Model 3, HR (95% CI) | Reference | 0.97 (0.77-1.22) | 0.790 |

| Incident HF hospitalization | |||

| n/N (%) | 563/3286 (17.13) | 90/364 (24.73) | <0.001 |

| Model 1, HR (95% CI) | Reference | 1.27 (1.01-1.59) | 0.040 |

| Model 2, HR (95% CI) | Reference | 1.21 (0.97-1.53) | 0.095 |

| Model 3, HR (95% CI) | Reference | 1.08 (0.86-1.36) | 0.513 |

| Death | |||

| n/N (%) | 1402/3286 (42.67) | 214/364 (58.79) | <0.001 |

| Model 1, HR (95% CI) | Reference | 1.14 (0.98-1.32) | 0.083 |

| Model 2, HR (95% CI) | Reference | 1.08 (0.93-1.26) | 0.300 |

| Model 3, HR (95% CI) | Reference | 1.05 (0.91-1.23) | 0.491 |

| Cardiovascular death | |||

| n/N (%) | 624/3286 (18.99) | 105/364 (28.85) | <0.001 |

| Model 1, HR (95% CI) | Reference | 1.26 (1.02-1.56) | 0.030 |

| Model 2, HR (95% CI) | Reference | 1.17 (0.94-1.44) | 0.160 |

| Model 3, HR (95% CI) | Reference | 1.08 (0.87-1.34) | 0.474 |

Model 1: adjusted for age and race; model 2: model 1 plus total cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, systolic blood pressure, antihypertensive medication use, current smoking, diabetes status, body mass index, lipid-lowering medication use, estimated glomerular filtration rate, log-testosterone, and log-SHBG; model 3: model 2 plus NT-proBNP.

Abbreviations: CHD, coronary heart disease; CI, confidence interval; DHEA-S, dehydroepiandrosterone-sulfate; HF, heart failure; HR, hazard ratio.

Table 6.

Association of Post–Visit 4 Incident CVD and DHEA-S (at or Above vs Below 15th Percentile for DHEA-S) in Men

| DHEA-S (µg/dL) | P Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 55.4-632.7 | 2.7-55.3 | ||

| Incident CHD | |||

| n/N (%) | 692/3103 (22.30) | 144/547 (26.33) | 0.039 |

| Model 1, HR (95% CI) | Reference | 1.14 (0.95-1.37) | 0.149 |

| Model 2, HR (95% CI) | Reference | 1.10 (0.91-1.32) | 0.328 |

| Model 3, HR (95% CI) | Reference | 1.07 (0.89-1.29) | 0.469 |

| Incident HF hospitalization | |||

| n/N (%) | 514/3103 (16.56) | 139/547 (25.41) | <0.001 |

| Model 1, HR (95% CI) | Reference | 1.39 (1.15-1.68) | 0.001 |

| Model 2, HR (95% CI) | Reference | 1.30 (1.07-1.58) | 0.007 |

| Model 3, HR (95% CI) | Reference | 1.18 (0.97-1.43) | 0.101 |

| Death | |||

| n/N (%) | 1310/3103 (42.22) | 306/547 (55.94) | <0.001 |

| Model 1, HR (95% CI) | Reference | 1.13 (1.00-1.28) | 0.060 |

| Model 2, HR (95% CI) | Reference | 1.07 (0.94-1.22) | 0.276 |

| Model 3, HR (95% CI) | Reference | 1.04 (0.91-1.19) | 0.536 |

| Cardiovascular death | |||

| n/N (%) | 577/3103 (18.59) | 152/547 (27.79) | <0.001 |

| Model 1, HR (95% CI) | Reference | 1.28 (1.07-1.54) | 0.007 |

| Model 2, HR (95% CI) | Reference | 1.17 (0.97-1.41) | 0.097 |

| Model 3, HR (95% CI) | Reference | 1.09 (0.91-1.32) | 0.358 |

Model 1: adjusted for age and race; model 2: model 1 plus total cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, systolic blood pressure, antihypertensive medication use, current smoking, diabetes status, body mass index, lipid-lowering medication use, estimated glomerular filtration rate, log-testosterone, and log-SHBG; model 3: model 2 plus NT-proBNP.

Abbreviations: CHD, coronary heart disease; CI, confidence interval; DHEA-S, dehydroepiandrosterone-sulfate; HF, heart failure; HR, hazard ratio.

In women, DHEA-S levels below the lowest 15th (27.4 µg/dL) and 10th (21.9 µg/dL) percentiles were significantly associated with increased risk for incident HF hospitalization (HR 1.42; 95% CI, 1.13-1.79 and HR 1.54; 95% CI, 1.17-2.03, respectively) and cardiovascular death (HR 1.43. 95% CI, 1.13-1.82 and HR 1.60; 95% CI, 1.21-2.12) after model 2 adjustment. DHEA-S levels below the lowest 25th percentile (37.1 µg/dL) and the lowest 15th percentile were both significantly associated with increased risk for death (HR 1.19; 95% CI, 1.03-1.37 and HR 1.23; 95% CI, 1.04-1.45, respectively). There was no significant association between DHEA-S and incident CHD in women (Tables 4, 8-10). In women but not in men, association of low DHEA-S level with HF hospitalization and death continued to be significant even after adjustment for NT-proBNP (Tables 5-10). Sensitivity analyses assessing association between DHEA-S and CVD outcomes involving competing risk with nonevent death yielded similar results to the primary analyses in men and women (data not shown).

Table 8.

Association of Post–Visit 4 Incident CVD and DHEA-S (at or Above vs Below 25th Percentile for DHEA-S) in Postmenopausal Women

| DHEA-S (µg/dL) | P Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 37.1-541.3 | 0-37.0 | ||

| Incident CHD | |||

| n/N (%) | 416/3338 (12.46) | 152/1155 (13.16) | 0.539 |

| Model 1, HR (95% CI) | Reference | 1.03 (0.85-1.24) | 0.795 |

| Model 2, HR (95% CI) | Reference | 0.98 (0.76-1.27) | 0.894 |

| Model 3, HR (95% CI) | Reference | 0.99 (0.77-1.28) | 0.943 |

| Incident HF hospitalization | |||

| n/N (%) | 592/3338 (17.74) | 259/1155 (22.42) | <0.001 |

| Model 1, HR (95% CI) | Reference | 1.21 (1.04-1.40) | 0.011 |

| Model 2, HR (95% CI) | Reference | 1.12 (0.91-1.38) | 0.279 |

| Model 3, HR (95% CI) | Reference | 1.11 (0.90-1.37) | 0.328 |

| Death | |||

| n/N (%) | 1126/3338 (33.73) | 500/1155 (43.29) | <0.001 |

| Model 1, HR (95% CI) | Reference | 1.15 (1.04-1.28) | 0.008 |

| Model 2, HR (95% CI) | Reference | 1.19 (1.03-1.37) | 0.017 |

| Model 3, HR (95% CI) | Reference | 1.20 (1.04-1.38) | 0.014 |

| Cardiovascular death | |||

| n/N (%) | 511/3338 (15.31) | 240/1155 (20.78) | <0.001 |

| Model 1, HR (95% CI) | Reference | 1.24 (1.06-1.45) | 0.006 |

| Model 2, HR (95% CI) | Reference | 1.17 (0.95-1.45) | 0.145 |

| Model 3, HR (95% CI) | Reference | 1.18 (0.95-1.46) | 0.135 |

Model 1: adjusted for age and race; model 2: model 1 plus total cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, systolic blood pressure, antihypertensive medication use, current smoking, diabetes status, body mass index, lipid-lowering medication use, estimated glomerular filtration rate, log-testosterone, log-SHBG, and current hormonal therapy use; model 3: model 2 plus N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide.

Abbreviations: CHD, coronary heart disease; CI, confidence interval; DHEA-S, dehydroepiandrosterone-sulfate; HF, heart failure; HR, hazard ratio.

Table 10.

Association of Post–Visit 4 Incident CVD and DHEA-S (at or Above vs Below 10th Percentile for DHEA-S) in Postmenopausal Women

| DHEA-S (µg/dL) | P Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 21.9-541.3 | 0-21.8 | ||

| Incident CHD | |||

| n/N (%) | 496/4042 (12.27) | 72/451 (15.96) | 0.025 |

| Model 1, HR (95% CI) | Reference | 1.32 (1.03-1.70) | 0.027 |

| Model 2, HR (95% CI) | Reference | 1.40 (0.99-1.98) | 0.059 |

| Model 3, HR (95% CI) | Reference | 1.44 (1.02-2.04) | 0.039 |

| Incident HF hospitalization | |||

| n/N (%) | 730/4042 (18.06) | 121/451 (26.83) | <0.001 |

| Model 1, HR (95% CI) | Reference | 1.50 (1.23-1.81) | <0.001 |

| Model 2, HR (95% CI) | Reference | 1.54 (1.17-2.03) | 0.002 |

| Model 3, HR (95% CI) | Reference | 1.61 (1.23-2.12) | 0.001 |

| Death | |||

| n/N (%) | 1420/4042 (35.13) | 206/451 (45.68) | <0.001 |

| Model 1, HR (95% CI) | Reference | 1.23 (1.06-1.42) | 0.006 |

| Model 2, HR (95% CI) | Reference | 1.21 (0.99-1.47) | 0.063 |

| Model 3, HR (95% CI) | Reference | 1.23 (1.01-1.50) | 0.042 |

| Cardiovascular death | |||

| n/N (%) | 639/4042 (15.81) | 112/451 (24.83) | <0.001 |

| Model 1, HR (95% CI) | Reference | 1.51 (1.23-1.85) | <0.001 |

| Model 2, HR (95% CI) | Reference | 1.60 (1.21-2.12) | 0.001 |

| Model 3, HR (95% CI) | Reference | 1.69 (1.27-2.25) | <0.001 |

Model 1: adjusted for age and race; model 2: model 1 plus total cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, systolic blood pressure, antihypertensive medication use, current smoking, diabetes status, body mass index, lipid-lowering medication use, estimated glomerular filtration rate, log-testosterone, log-SHBG, and current hormonal therapy use; model 3: model 2 plus N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide.

Abbreviations: CHD, coronary heart disease; CI, confidence interval; DHEA-S, dehydroepiandrosterone-sulfate; HF, heart failure; HR, hazard ratio.

Table 5.

Association of Post–Visit 4 Incident CVD and DHEA-S (at or Above vs Below 25th Percentile for DHEA-S) in Men

| DHEA-S (µg/dL) | P Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 70.0-632.7 | 2.7-69.9 | ||

| Incident CHD | |||

| n/N (%) | 608/2735 (22.23) | 228/915 (24.92) | 0.094 |

| Model 1, HR (95% CI) | Reference | 1.09 (0.93-1.27) | 0.294 |

| Model 2, HR (95% CI) | Reference | 1.08 (0.92-1.26) | 0.362 |

| Model 3, HR (95% CI) | Reference | 1.05 (0.89-1.23) | 0.556 |

| Incident HF hospitalization | |||

| n/N (%) | 455/2735 (16.64) | 198/915 (21.64) | 0.001 |

| Model 1, HR (95% CI) | Reference | 1.17 (0.99-1.39) | 0.067 |

| Model 2, HR (95% CI) | Reference | 1.16 (0.97-1.37) | 0.100 |

| Model 3, HR (95% CI) | Reference | 1.05 (0.88-1.25) | 0.598 |

| Death | |||

| n/N (%) | 1118/2735 (40.88) | 498/915 (54.43) | <0.001 |

| Model 1, HR (95% CI) | Reference | 1.14 (1.03-1.27) | 0.014 |

| Model 2, HR (95% CI) | Reference | 1.12 (1.01-1.25) | 0.036 |

| Model 3, HR (95% CI) | Reference | 1.08 (0.96-1.20) | 0.184 |

| Cardiovascular death | |||

| n/N (%) | 500/2735 (18.28) | 229/915 (25.03) | <0.001 |

| Model 1, HR (95% CI) | Reference | 1.18 (1.00-1.38) | 0.043 |

| Model 2, HR (95% CI) | Reference | 1.15 (0.98-1.35) | 0.095 |

| Model 3, HR (95% CI) | Reference | 1.06 (0.90-1.25) | 0.501 |

Model 1: adjusted for age and race; model 2: model 1 plus total cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, systolic blood pressure, antihypertensive medication use, current smoking, diabetes status, body mass index, lipid-lowering medication use, estimated glomerular filtration rate, log-testosterone, and log-SHBG; model 3: model 2 plus N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide.

Abbreviations: CHD, coronary heart disease; CI, confidence interval; DHEA-S, dehydroepiandrosterone-sulfate; HF, heart failure; HR, hazard ratio.

Table 9.

Association of Post–Visit 4 Incident CVD and DHEA-S (at or Above vs Below 15th Percentile for DHEA-S) in Postmenopausal Women

| DHEA-S (µg/dL) | P Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 27.3-541.3 | 0-27.2 | ||

| Incident CHD | |||

| n/N (%) | 473/3817 (12.39) | 95/676 (14.05) | 0.231 |

| Model 1, HR (95% CI) | Reference | 1.13 (0.91-1.41) | 0.280 |

| Model 2, HR (95% CI) | Reference | 1.11 (0.82-1.50) | 0.483 |

| Model 3, HR (95% CI) | Reference | 1.14 (0.84-1.53) | 0.407 |

| Incident HF hospitalization | |||

| n/N (%) | 683/3817 (17.89) | 168/676 (24.85) | <0.001 |

| Model 1, HR (95% CI) | Reference | 1.38 (1.17-1.64) | <0.001 |

| Model 2, HR (95% CI) | Reference | 1.42 (1.13-1.79) | 0.003 |

| Model 3, HR (95% CI) | Reference | 1.44 (1.14-1.82) | 0.002 |

| Death | |||

| n/N (%) | 1316/3817 (34.48) | 310/676 (45.86) | <0.001 |

| Model 1, HR (95% CI) | Reference | 1.24 (1.09-1.40) | 0.001 |

| Model 2, HR (95% CI) | Reference | 1.23 (1.04-1.45) | 0.013 |

| Model 3, HR (95% CI) | Reference | 1.24 (1.05-1.47) | 0.010 |

| Cardiovascular death | |||

| n/N (%) | 1316/3817 (34.48) | 310/676 (45.86) | <0.001 |

| Model 1, HR (95% CI) | Reference | 1.41 (1.18-1.68) | <0.001 |

| Model 2, HR (95% CI) | Reference | 1.43 (1.13-1.82) | 0.003 |

| Model 3, HR (95% CI) | Reference | 1.44 (1.13-1.84) | 0.003 |

Model 1: adjusted for age and race; model 2: model 1 plus total cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, systolic blood pressure, antihypertensive medication use, current smoking, diabetes status, body mass index, lipid-lowering medication use, estimated glomerular filtration rate, log-testosterone, log-SHBG, and current hormonal therapy use; model 3: model 2 plus N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide.

Abbreviations: CHD, coronary heart disease; CI, confidence interval; DHEA-S, dehydroepiandrosterone-sulfate; HF, heart failure; HR, hazard ratio.

Change in DHEA-S level and risk for events

The median (25th, 75th percentile) absolute change in DHEA-S between visits 4 and 5 was –27.2 (–55.7, –6.9) µg/dL in men and –4.7 (–24.3, 10.4) µg/dL in women. When assessed by quartiles, the degree of change in DHEA-S varied widely among individuals as shown in Table 11. Baseline total cholesterol, smoking, log-testosterone and log-SHBG measured at visit 4 were associated with decrease in DHEA-S concentration in men, whereas black race and baseline HDL-C were negatively associated. Similarly, total cholesterol and log-testosterone measured at visit 4 were associated with decrease in DHEA-S levels in women, whereas black race was negatively associated (Table 11).

Table 11.

Association of Cardiovascular Risk Factors at Visit 4 and Percent Change in DHEA-S by Quartiles in Men and Postmenopausal Women

| Men | Women | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quartiles of ∆DHEA-S (%) | ||||||||

| Q1: 939.7 to -10.0 (N = 561) | Q2: -10.2 to -31.4 (N = 561) | Q3: -31.5 to -47.8 (N = 561) | Q4: -47.9 to -97.8 (N = 561) | Q1: 22.5-1118.8 (N = 660) | Q2: 22.5 to -10.9 (N = 661) | Q3: -11.0 to -38.5 (N = 661) | Q4: -38.5 to -97.7 (N = 661) | |

| Β-coefficients (95% CI) | ||||||||

| Age (y) | Reference | 0.002 (-0.02, 0.03) | -0.01 (-0.03, 0.02) | -0.003 (-0.03, 0.02) | Reference | 0.02 (-0.004, 0.05) | 0.01 (0.02, 0.04) | -0.002 (-0.03, 0.03) |

| African American | -0.74 (-1.08, -0.41) | -0.83 (-1.17, -0.49) | -1.17 (-1.54, -0.81) | -0.47 (-0.82, -0.12) | -0.44 (-0.79, -0.09) | -1.13 (-1.52, -0.75) | ||

| Total cholesterol (mg/dL) | 0.005 (0.002, 0.009) | 0.009 (0.005, 0.013) | 0.009 (0.005, 0.013) | 0.003 (-0.001, 0.007) | 0.003 (-0.001, 0.007) | 0.004 (0.0003, 0.008) | ||

| HDL-C (mg/dL) | -0.007 (-0.017, 0.004) | -0.011 (-0.021, -0.0004) | -0.010 (-0.021, 0.0003) | 0.004 (-0.006, 0.013) | 0.001 (-0.008, 0.011) | -0.001 (-0.010, 0.009) | ||

| SBP (mm Hg) | -0.003 (-0.010, 0.005) | -0.003 (-0.011, 0.004) | -0.006 (-0.014, 0.002) | 0.0005 (-0.0007, 0.008) | -0.0001 (-0.008, 0.008) | 0.002 (-0.006, 0.010) | ||

| Antihypertensive medication use | -0.05 (-0.32, 0.22) | -0.03 (-0.30, 0.24) | 0.23 (-0.04, 0.49) | -0.05 (-0.35, 0.26) | -0.15 (-0.46, 0.16) | 0.18 (-0.13, 0.49) | ||

| Current smoker | -0.25 (-0.67, 0.17) | -0.04 (-0.44, 0.37) | 0.52 (0.14, 0.90) | -0.16 (-0.67, 0.34) | 0.11 (-0.38, 0.60) | 0.44 (-0.04, 0.91) | ||

| Diabetes | -0.27 (-0.65, 0.11) | 0.01 (-0.35, 0.37) | -0.04 (-0.40, 0.32) | -0.18 (-0.63, 0.27) | -0.25 (-0.70, 0.21) | -0.08 (-0.53, 0.38) | ||

| BMI (kg/m2) | -0.01 (-0.04, 0.03) | 0.01 (-0.02, 0.05) | 0.02 (-0.01, 0.06) | -0.02 (-0.05, 0.003) | -0.002 (-0.03, 0.02) | 0.002 (-0.02, 0.03) | ||

| Lipid-lowering medication use | -0.02 (-0.38, 0.35) | 0.16 (-0.20, 0.52) | 0.19 (-0.16, 0.54) | -0.34 (-0.78, 0.10) | -0.20 (-0.63, 0.23) | -0.09 (-0.52, 0.33) | ||

| eGFR (mL/min/1.73 m2) | -0.007 (-0.016, 0.003) | -0.002 (-0.012, 0.008) | -0.003 (-0.013, 0.007) | 0.003 (-0.006, 0.013) | -0.001 (-0.010, 0.009) | 0.006 (-0.004, 0.016) | ||

| log-testosterone | 0.49 (0.13, 0.86) | 0.37 (0.01, 0.73) | -0.02 (-0.32, 0.28) | 0.63 (0.32, 0.94) | 0.80 (0.48, 1.11) | 1.02 (0.70, 1.33) | ||

| log-SHBG | 0.02 (-0.32, 0.35) | 0.33 (-0.02, 0.68) | 0.34 (0.001, 0.67) | -0.10 (-0.36, 0.16) | -0.15 (-0.40, 0.11) | -0.03 (-0.30, 0.23) | ||

| Hormonal therapy use | N/A | N/A | N/A | -0.17 (-0.51, 0.17) | -0.001 (-0.34, 0.34) | -0.15 (-0.51, 0.20) | ||

B-coefficients calculated by multinomial logistic regression. Bolded values indicate statistical significance (P < 0.05).

Abbreviations: BMI = body mass index; CI = confidence interval; DHEA-S, dehydroepiandrosterone-sulfate; eGFR = estimated glomerular filtration rate; HDL-C = high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; N/A = not applicable; Q = quartile; SBP = systolic blood pressure.

Among 1575 men without prevalent CVD at visit 5, 141 incident HF hospitalizations, 99 incident CHD events, and 254 deaths occurred over a median follow-up of ~5.5 years after visit 5. We observed increasing rates of HF hospitalization with a greater percentage decrease in DHEA-S levels over time in men. In multivariable models, a greater percentage decrease in DHEA-S level was associated with increased risk for HF hospitalization (4th vs 1st quartiles: HR 1.94; 95% CI, 1.11-3.39). There was no significant association observed between percent change in DHEA-S with CHD and death in men (Table 12).

Table 12.

Association of Post–Visit 5 Incident CVD and Percent Change in DHEA-S [(DHEA-Svisit 5 – DHEA-Svisit 4)/DHEA-Svisit 4 × 100] Quartiles in Men

| ΔDHEA-S Quartiles (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Q1 (-8.7, 293.9) | Q2 (-29.1, -8.8) | Q3 (-46.0, -29.1) | Q4 (-97.8, -46.0) | |

| Incident CHD | ||||

| n/N (%) | 25/393 (6.36) | 21/394 (5.33) | 23/394 (5.84) | 26/394 (6.60) |

| Model 1, HR (95% CI) | Reference | 0.71 (0.39-1.27) | 0.78 (0.44-1.38) | 0.92 (0.53-1.60) |

| Model 2, HR (95% CI) | Reference | 0.69 (0.38-1.26) | 0.71 (0.39-1.28) | 0.86 (0.48-1.54) |

| Incident HF hospitalization | ||||

| n/N (%) | 23/393 (5.85) | 27/394 (6.85) | 32/394 (8.12) | 43/394 (10.91) |

| Model 1, HR (95% CI) | Reference | 1.24 (0.70-2.17) | 1.43 (0.83-2.45) | 2.25 (1.35-3.76) |

| Model 2, HR (95% CI) | Reference | 1.24 (0.69-2.25) | 1.18 (0.65-2.14) | 1.94 (1.11-3.39) |

| Death | ||||

| n/N (%) | 60/393 (15.27) | 53/394 (13.45) | 44/394 (11.17) | 73/394 (18.53) |

| Model 1, HR (95% CI) | Reference | 0.84 (0.58-1.22) | 0.68 (0.46-1.01) | 1.35 (0.96-1.91) |

| Model 2, HR (95% CI) | Reference | 0.89 (0.60-1.32) | 0.63 (0.41-0.97) | 1.39 (0.95-2.04) |

Model 1: adjusted for age and race; model 2: model 1 plus total cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, systolic blood pressure, antihypertensive medication use, current smoking, diabetes status, body mass index, lipid-lowering medication use, estimated glomerular filtration rate, log-testosterone, and log-SHBG. P trend for linearity of hazard ratio of proportional hazard regression model is calculated based on the results of Wald χ 2 test on linearity hypothesis of ordered percentage ΔDHEA-S quartiles.

CHD, coronary heart disease; CI, confidence interval; DHEA, dehydroepiandrosterone; DHEA-S, dehydroepiandrosterone-sulfate; HF, heart failure; HR, hazard ratio; Q, quartile.

During this follow-up period, 189 incident HF hospitalizations, 80 incident CHD events, and 327 deaths occurred among the 2131 women who were free of prevalent CVD at visit 5. In contrast with results in men, we did not observe significant associations between change in DHEA-S level with outcome events after visit 5 in women (Table 13).

Table 13.

Association of Post–Visit 5 Incident CVD and Percent Change in DHEA-S [(DHEA-Svisit 5 – DHEA-Svisit 4)/DHEA-Svisit 4 × 100] Quartiles in Women

| ΔDHEA-S Quartiles (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Q1 (23.3, 1118.8) | Q2 (-9.1, 23.2) | Q3 (-35.2, -9.2) | Q4 (-97.7, -35.3) | |

| Incident CHD | ||||

| n/N (%) | 16/532 (3.01) | 17/533 (3.19) | 14/533 (2.63) | 15/533 (2.81) |

| Model 1, HR (95% CI) | Reference | 1.08 (0.54-2.14) | 0.89 (0.43-1.84) | 0.98 (0.48-2.00) |

| Model 2, HR (95% CI) | Reference | 0.82 (0.35-1.92) | 0.66 (0.27-1.63) | 0.59 (0.23-1.52) |

| Incident HF hospitalization | ||||

| n/N (%) | 37/532 (6.95) | 37/533 (6.94) | 27/533 (5.07) | 51/533 (9.57) |

| Model 1, HR (95% CI) | Reference | 0.99 (0.63-1.56) | 0.75 (0.46-1.24) | 1.50 (0.98-2.30) |

| Model 2, HR (95% CI) | Reference | 1.03 (0.56-1.89) | 0.80 (0.41-1.55) | 1.25 (0.68-2.28) |

| Death | ||||

| n/N (%) | 61/532 (11.47) | 70/533 (13.13) | 56/533 (10.51) | 73/533 (13.70) |

| Model 1, HR (95% CI) | Reference | 1.14 (0.81-1.61) | 0.96 (0.67-1.38) | 1.31 (0.93-1.85) |

| Model 2, HR (95% CI) | Reference | 1.15 (0.72-1.83) | 0.97 (0.59-1.60) | 1.31 (0.81-2.12) |

Model 1: adjusted for age and race; model 2: model 1 plus total cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, systolic blood pressure, antihypertensive medication use, current smoking, diabetes status, body mass index, lipid-lowering medication use, estimated glomerular filtration rate, log-testosterone, log-SHBG, and current hormonal therapy use. P trend for linearity of hazard ratio of proportional hazard regression model is calculated based on the results of Wald χ 2 test on linearity hypothesis of ordered percentage ΔDHEA-S quartiles.

CHD, coronary heart disease; CI, confidence interval; DHEA, dehydroepiandrosterone; DHEA-S, dehydroepiandrosterone-sulfate; HF, heart failure; HR, hazard ratio; Q, quartile.

Association between DHEA-S and markers of subclinical myocardial injury

In cross-sectional analyses at ARIC visit 4, DHEA-S levels below the lowest 15th percentile sex-specific cutpoint (55.4 µg/dL in men and 27.3 µg/dL in women) were significantly associated with higher log-hs-TnT (P = 0.014) and log-NT-proBNP (P = 0.003) in men without prevalent CVD and with higher log-hs-TnT (P = 0.021) but not with log-NT-proBNP in women without prevalent CVD. In cross-sectional analyses at ARIC visit 5, DHEA-S below 55.4 µg/dL in men free of prevalent CVD was associated with higher log-NT-proBNP (P = 0.002) but not with log-hs-TnT. In women without prevalent CVD at visit 5, cross-sectional analyses showed that DHEA-S levels below 27.3 µg/dL were significantly associated with higher log-NT-proBNP (P = 0.037) but not with log-hs-TnT.

Association among DHEA-S, plasma proteins, and pathways

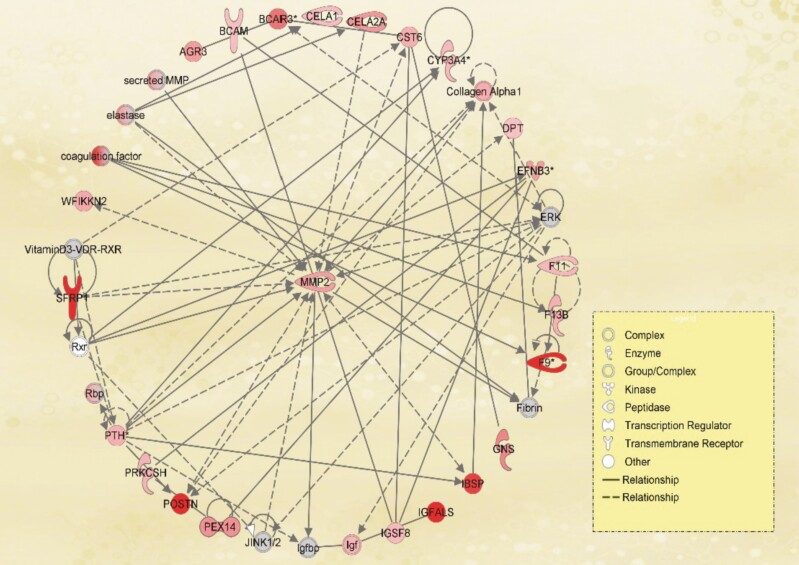

We identified 271 plasma proteins from SomaLogic proteomics assay showing a significant association with DHEA-S (Table 14). The top 5 proteomics hits were: DNA repair protein RAD51, agouti-related protein (ART), histone H2B type 2E, histone type 2B type 3B, and pro-opiomelanocortin (POMC). IPA canonical pathway analysis identified 12 pathways enriched by the genes significantly associated with DHEA-S level. The top pathways are: Coagulation System, Intrinsic Prothrombin Activation Pathway, Inhibition of Matrix Metalloproteases, and LXR/RXR Activation (Table 15). In IPA, the most significant network was “Cardiovascular Disease, Connective Tissue Development and Function, Organismal Injury and Abnormalities,” with 23 significant proteins including matrix metalloproteinase 2 (MMP2), secreted frizzled-related protein 1, periostin, collagen alpha 1, and insulin-like growth factor (Fig. 4; Table 16).

Table 14.

Proteins/genes Showing Significant (After Adjustment for Multiple Testing) Association With DHEA-S Level in Blood

| uniprot_id | entrez_gene_id | Target | Beta | R 2 | P | FDR_P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| O75771 | 5892 | RA51D | 0.480808 | 0.258673 | 2.28E-42 | 1.11E-38 |

| O00253 | 181 | ART | 0.447529 | 0.239387 | 1.28E-21 | 3.12E-18 |

| Q16778 | 8349 | H2B2E | -0.20901 | 0.233034 | 7.35E-15 | 1.19E-11 |

| Q8N257 | 128312 | H2B3B | -0.18156 | 0.231212 | 6.35E-13 | 7.74E-10 |

| P01189 | 5443 | POMC | 0.232643 | 0.230685 | 2.30E-12 | 1.87E-09 |

| Q9NQ30 | 11082 | Endocan | -0.32985 | 0.230567 | 3.08E-12 | 2.15E-09 |

| Q6NUJ1 | 768239 | SAPL1 | 0.180964 | 0.229209 | 8.56E-11 | 5.22E-08 |

| Q8N474 | 6422 | SARP-2 | -0.28328 | 0.228345 | 7.11E-10 | 3.85E-07 |

| Q8N2S1 | 8425 | LTBP4 | -0.33178 | 0.227764 | 2.96E-09 | 1.44E-06 |

| P02743 | 325 | SAP | 0.383509 | 0.227309 | 9.07E-09 | 4.02E-06 |

| P00740 | 2158 | Coagulation factor IX | 0.376573 | 0.226816 | 3.05E-08 | 1.24E-05 |

| Q99983 | 4958 | OMD | -0.18529 | 0.226769 | 3.42E-08 | 1.28E-05 |

| O95319 | 10659 | CELF2 | -0.22058 | 0.226686 | 4.20E-08 | 1.46E-05 |

| Q9H4D0 | 64084 | CSTN2 | -0.23727 | 0.226631 | 4.80E-08 | 1.56E-05 |

| Q96KN2 | 84735 | CNDP1 | 0.153012 | 0.226447 | 7.57E-08 | 2.31E-05 |

| P35858 | 3483 | IGFALS | 0.226364 | 0.226008 | 2.23E-07 | 6.40E-05 |

| P17655 | 824 | CAN2 | -0.20887 | 0.225969 | 2.46E-07 | 6.67E-05 |

| Q14512 | 9982 | FGFP1 | -0.17817 | 0.225929 | 2.72E-07 | 6.73E-05 |

| Q9NXS2 | 54814 | QPCTL | -0.24093 | 0.225922 | 2.76E-07 | 6.73E-05 |

| Q15063 | 10631 | Periostin | -0.2307 | 0.225859 | 3.23E-07 | 7.50E-05 |

| P07585 | 1634 | Bone proteoglycan II | -0.28552 | 0.225816 | 3.59E-07 | 7.96E-05 |

| P01023 | 2 | a2-Macroglobulin | -0.24517 | 0.225636 | 5.60E-07 | 0.000115 |

| Q96DX5 | 140462 | ASB9 | -0.18962 | 0.225631 | 5.68E-07 | 0.000115 |

| Q8TAT2 | 143282 | FGFP3 | -0.22291 | 0.225589 | 6.30E-07 | 0.000123 |

| P00751 | 629 | Factor B | 0.436279 | 0.225482 | 8.20E-07 | 0.000154 |

| Q13822 | 5168 | ENPP2 | -0.20993 | 0.225327 | 1.20E-06 | 0.000216 |

| Q8N2Q7 | 22871 | NLGN1 | -0.25853 | 0.225314 | 1.24E-06 | 0.000216 |

| O60938 | 11081 | KERA | -0.29788 | 0.225274 | 1.37E-06 | 0.00023 |

| Q11128 | 2527 | FUT5 | 0.161476 | 0.225243 | 1.48E-06 | 0.000233 |

| Q6ZMJ2 | 286133 | SCAR5 | -0.1639 | 0.225244 | 1.48E-06 | 0.000233 |

| P21815 | 3381 | BSP | -0.12946 | 0.2252 | 1.65E-06 | 0.000237 |

| Q9HC56 | 5101 | PCDH9 | -0.21495 | 0.225189 | 1.70E-06 | 0.000237 |

| Q01105 | 6418 | SET | 0.444297 | 0.225214 | 1.59E-06 | 0.000237 |

| Q8N1Q1 | 377677 | Carbonic anhydrase XIII | -0.08848 | 0.22519 | 1.69E-06 | 0.000237 |

| P41221 | 7474 | WNT5A | -0.19134 | 0.225067 | 2.30E-06 | 0.000308 |

| Q9GZM7 | 64129 | TINAL | -0.24707 | 0.225059 | 2.34E-06 | 0.000308 |

| P02786 | 7037 | TR | -0.20771 | 0.22489 | 3.56E-06 | 0.000457 |

| Q9GZZ8 | 90070 | Lacritin | 0.11826 | 0.224823 | 4.20E-06 | 0.000525 |

| Q9NRN5 | 56944 | OLFL3 | -0.30075 | 0.224796 | 4.50E-06 | 0.000549 |

| P55083 | 4239 | MFAP4 | -0.14158 | 0.224732 | 5.28E-06 | 0.000628 |

| Q96I82 | 81621 | KAZD1 | -0.20964 | 0.224647 | 6.52E-06 | 0.000757 |

| P16860 | 4879 | N-terminal pro-BNP | -0.07352 | 0.224628 | 6.84E-06 | 0.000776 |

| O43300 | 26045 | LRRT2 | -0.23181 | 0.224548 | 8.34E-06 | 0.000924 |

| O14594 | 1463 | CSPG3 | -0.17316 | 0.224469 | 1.01E-05 | 0.001071 |

| P21810 | 633 | BGN | -0.21511 | 0.224422 | 1.14E-05 | 0.001183 |

| P40261 | 4837 | NNMT | -0.1501 | 0.224369 | 1.30E-05 | 0.001321 |

| P31949 | 6282 | S100A11 | -0.20749 | 0.224241 | 1.80E-05 | 0.001765 |

| P35968 | 3791 | VEGF sR2 | 0.289372 | 0.224146 | 2.27E-05 | 0.002013 |

| P01160 | 4878 | ANP | -0.20488 | 0.224165 | 2.17E-05 | 0.002013 |

| P19957 | 5266 | Elafin | 0.13279 | 0.224149 | 2.26E-05 | 0.002013 |

| Q9HCB6 | 10418 | Spondin-1 | -0.25638 | 0.224147 | 2.27E-05 | 0.002013 |

| Q6P5S2 | 352999 | CF058 | 0.106764 | 0.224165 | 2.17E-05 | 0.002013 |

| O00453 | 7940 | LST1 | -0.18758 | 0.224128 | 2.38E-05 | 0.002035 |

| O75815 | 8412 | BCAR3 | -0.22442 | 0.224122 | 2.42E-05 | 0.002035 |

| O75056 | 9672 | SDC3 | 0.199752 | 0.224126 | 2.39E-05 | 0.002035 |

| Q9NR28 | 56616 | SMAC | -0.17309 | 0.224104 | 2.53E-05 | 0.002073 |

| Q8NBZ7 | 80146 | UXS1 | -0.22776 | 0.2241 | 2.55E-05 | 0.002073 |

| P16671 | 948 | CD36 ANTIGEN | -0.11126 | 0.224091 | 2.61E-05 | 0.002087 |

| Q9HDB5 | 9369 | NRX3B | -0.21411 | 0.224077 | 2.71E-05 | 0.002132 |

| P03950 | 283 | Angiogenin | 0.20488 | 0.224046 | 2.92E-05 | 0.00226 |

| Q13478 | 8809 | IL-18 Ra | -0.18794 | 0.224011 | 3.19E-05 | 0.002431 |

| Q9NR55 | 55509 | BATF3 | 0.197271 | 0.224004 | 3.24E-05 | 0.002431 |

| O75636 | 8547 | Ficolin-3 | 0.181142 | 0.223994 | 3.33E-05 | 0.002461 |

| P35442 | 7058 | TSP2 | -0.12423 | 0.223958 | 3.64E-05 | 0.00265 |

| P02747 | 714 | C1QC | 0.107406 | 0.223943 | 3.78E-05 | 0.002711 |

| P07355 | 302 | Annexin II | -0.17706 | 0.223924 | 3.97E-05 | 0.002766 |

| Q01844 | 2130 | EWS | -0.24469 | 0.223929 | 3.92E-05 | 0.002766 |

| P51654 | 2719 | Glypican 3 | -0.15709 | 0.223915 | 4.06E-05 | 0.002789 |

| Q9BWV1 | 91653 | BOC | -0.17999 | 0.223869 | 4.55E-05 | 0.003082 |

| P78504 | 182 | JAG1 | -0.22892 | 0.223838 | 4.92E-05 | 0.003243 |

| Q86VR8 | 24147 | FJX1 | -0.19436 | 0.223843 | 4.86E-05 | 0.003243 |

| P81172 | 57817 | LEAP-1 | 0.049993 | 0.223822 | 5.12E-05 | 0.003329 |

| P15090 | 2167 | FABPA | -0.17907 | 0.22379 | 5.55E-05 | 0.003561 |

| P56159 | 2674 | GFRa-1 | -0.20582 | 0.223769 | 5.85E-05 | 0.003658 |

| P01042 | 3827 | Kininogen, HMW, 2 chain | 0.13245 | 0.223774 | 5.79E-05 | 0.003658 |

| Q9Y5H3 | 56106 | PCDGA | -0.15197 | 0.223763 | 5.94E-05 | 0.003667 |

| Q9NX14 | 54539 | NDUBB | 0.181309 | 0.223756 | 6.04E-05 | 0.003682 |

| Q9NP95 | 26281 | FGF-20 | -0.19916 | 0.223745 | 6.22E-05 | 0.003745 |

| Q99726 | 7781 | ZNT3 | 0.155041 | 0.223735 | 6.37E-05 | 0.003789 |

| O15444 | 6370 | TECK | -0.09392 | 0.223724 | 6.55E-05 | 0.003849 |

| P10721 | 3815 | SCF sR | 0.164413 | 0.223717 | 6.67E-05 | 0.003873 |

| P54826 | 2619 | GAS1 | -0.24756 | 0.223709 | 6.81E-05 | 0.003907 |

| P0DMV9 | 3304 | HS71B | -0.2015 | 0.223697 | 7.01E-05 | 0.003975 |

| Q6UXI7 | 5212 | VITRN | -0.2078 | 0.223684 | 7.25E-05 | 0.004062 |

| Q8IW52 | 139065 | SLIK4 | -0.20884 | 0.223679 | 7.33E-05 | 0.004062 |

| P00441 | 6647 | SOD | -0.21088 | 0.223675 | 7.42E-05 | 0.004066 |

| P17693 | 3135 | HLA-G | -0.36303 | 0.223661 | 7.68E-05 | 0.004116 |

| P49006 | 65108 | MARCKSL1 | 0.236338 | 0.223664 | 7.62E-05 | 0.004116 |

| P39059 | 1306 | COFA1 | 0.316405 | 0.22364 | 8.09E-05 | 0.004254 |

| P31371 | 2254 | FGF9 | -0.22439 | 0.223635 | 8.20E-05 | 0.004254 |

| P15586 | 2799 | GNS | -0.15559 | 0.223636 | 8.18E-05 | 0.004254 |

| P02792 | 2512 | Ferritin light chain | 0.05308 | 0.223611 | 8.71E-05 | 0.004471 |

| P12273 | 5304 | PIP | 0.091678 | 0.223607 | 8.80E-05 | 0.004471 |

| Q9NZK5 | 51816 | CECR1 | -0.11927 | 0.223569 | 9.69E-05 | 0.004872 |

| Q9Y5C1 | 27329 | ANGL3 | -0.17967 | 0.223564 | 9.81E-05 | 0.004882 |

| Q13740 | 214 | ALCAM | -0.31501 | 0.223544 | 0.000103 | 0.004945 |

| O14791 | 8542 | Apo L1 | 0.216246 | 0.223541 | 0.000104 | 0.004945 |

| O95445 | 55937 | ApoM | 0.245202 | 0.223539 | 0.000104 | 0.004945 |

| Q5T7V8 | 92344 | GORAB | 0.200397 | 0.223554 | 0.0001 | 0.004945 |

Abbreviations: DHEA-S, dehydroepiandrosterone-sulfate; FDR, false discovery rate.

Table 15.

Canonical Pathways Identified by Ingenuity Pathway Analysis (IPA) of the Proteins Significantly Correlated With DHEA-S Level

| Ingenuity Canonical Pathways | -log(P value) | Molecules |

|---|---|---|

| Coagulation System | 3.58 | A2M, F10, F11, F13B, F9, KNG1, PLAT, SERPIND1 |

| Intrinsic Prothrombin Activation Pathway | 2.36 | COL1A1, F10, F11, F13B, F9, KLK14, KNG1 |

| Inhibition of Matrix Metalloproteases | 2.21 | A2M, MMP13, MMP2, THBS2, TIMP1, TIMP2 |

| LXR/RXR Activation | 2.16 | APOA1, APOA5, APOF, APOL1, APOM, CD14, CD36, HPX, IL36A, KNG1, RBP4, TNFRSF11B |

| Hepatic Fibrosis/Hepatic Stellate Cell Activation | 2.09 | A2M, CD14, COL15A1, COL1A1, ECE1, FAS, HGF, IGF1, IGF1R, KDR, MMP13, MMP2, TIMP1, TIMP2, TNFRSF11B |

| Clathrin-mediated Endocytosis Signaling | 1.8 | APOA1, APOF, APOL1, APOM, FGF19, FGF20, FGF9, HSPA8, IGF1, PPP3R1, RBP4, TFRC, UBC |

| Atherosclerosis Signaling | 1.71 | APOA1, APOF, APOL1, APOM, CD36, COL1A1, IL36A, MMP13, PLA2G5, PLA2R1, RBP4 |

| Cardiomyocyte Differentiation via BMP Receptors | 1.6 | BMP10, NPPA, NPPB |

| Neuroprotective Role of THOP1 in Alzheimer’s Disease | 1.56 | ECE1, F11, GZMA, HLA-G, HTRA1, KNG1, PRSS1, PRSS3, SST |

| Axonal Guidance Signaling | 1.49 | ADAM11, BMP1, BMP10, EFNB3, IGF1, LRRC4C, MMP13, MMP2, NRAS, NRP2, NTN1, NTRK3, PAK3, PLXNA1, PPP3R1, ROBO1, SDCBP, SEMA5A, SEMA6A, SLIT2, UNC5B, WNT5A |

| FXR/RXR Activation | 1.34 | APOA1, APOF, APOL1, APOM, FGF19, HPX, IL36A, KNG1, RBP4 |

DHEA-S, dehydroepiandrosterone-sulfate.

Figure 4.

The network of “Cardiovascular Disease, Connective Tissue Development and Function, Organismal Injury and Abnormalities” was found to be significantly associated with DHEA-S based on Ingenuity Pathway Analysis. Genes shown in red were significantly associated with DHEA-S level in blood. Intensity of the color reflects the level of significance. Genes shown in gray are the genes that were not significant or not included in the analysis but interact with at least 2 significant genes. DHEA-S, dehydroepiandrosterone-sulfate.

Table 16.

Rank of Biological Networks via Ingenuity Pathway Analysis (IPA), Based on Plasma Proteins From Aptamer Assay With Significant Association With DHEA-S

| Rank | Score | Top Diseases and Functions |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 39 | Cardiovascular Disease, Connective Tissue Development and Function, Organismal Injury and Abnormalities |

| 2 | 34 | Dermatological Diseases and Conditions, Inflammatory Disease, Organismal Injury and Abnormalities |

| 3 | 34 | Cellular Movement, Dermatological Diseases and Conditions, Organismal Injury and Abnormalities |

| 4 | 32 | Carbohydrate Metabolism, Connective Tissue Development and Function, Small Molecule Biochemistry |

| 5 | 30 | Cell-To-Cell Signaling and Interaction, Cellular Assembly and Organization, Nervous System Development and Function |

| 6 | 28 | Developmental Disorder, Hematological Disease, Protein Synthesis |

| 7 | 26 | Gene Expression, RNA Damage and Repair, RNA Post-Transcriptional Modification |

| 8 | 24 | Cellular Function and Maintenance, Molecular Transport, Small Molecule Biochemistry |

| 9 | 22 | Cellular Movement, Hematological System Development and Function, Immune Cell Trafficking |

| 10 | 22 | Cell-To-Cell Signaling and Interaction, Cellular Growth and Proliferation, Hematological System Development and Function |

| 11 | 20 | Cancer, Cellular Development, Cellular Growth and Proliferation |

| 12 | 18 | Cell-To-Cell Signaling and Interaction, Cellular Assembly and Organization, Inflammatory Response |

| 13 | 16 | Cardiovascular System Development and Function, Cellular Development, Cellular Function and Maintenance |

| 14 | 16 | Connective Tissue Development and Function, Skeletal and Muscular System Development and Function, Tissue Development |

| 15 | 14 | Nutritional Disease, Organismal Development, Protein Synthesis |

| 16 | 13 | Amino Acid Metabolism, Protein Synthesis, Small Molecule Biochemistry |

| 17 | 8 | Cancer, Cellular Movement, Inflammatory Disease |

| 18 | 2 | Cancer, Cell Death and Survival, Cellular Development |

| 19 | 2 | Developmental Disorder, Ophthalmic Disease, Organismal Injury and Abnormalities |

| 20 | 2 | Cancer, Organismal Injury and Abnormalities |

Discussion

In our study, DHEA-S levels showed a general decrease with age in older adults. Men had relatively higher DHEA-S levels but also had more dramatic decline in levels with age compared with women. Low DHEA-S was associated with increased risk for subclinical myocardial injury, HF hospitalization, and death but not CHD. We further found that greater decrease in DHEA-S over time was associated with higher risk for HF hospitalization in men. Finally, we noted significant association between DHEA-S and pathways involved in cardiac remodeling in proteomics analysis.

Circulating DHEA-S is thought to decrease with aging (35-38). Although DHEA-S decreased in a majority of individuals in our study and those of others, we noted significant heterogeneity in the degree of change among individuals over the 15-year period between ARIC visits 4 and 5. This finding from a large community cohort builds on results from 2 smaller studies showing a wide range of change in DHEA-S levels with advancing age (37, 38). We show that higher baseline total cholesterol and testosterone were associated with a greater decrease in DHEA-S levels in both men and women. In men, smoking and higher SHBG at baseline was also found to be associated with a greater decrease in DHEA-S. Moreover, there appears to be a racial difference with respect to change in DHEA-S with aging, with black race associated with less decline in DHEA-S. Differences in DHEA-S by ethnicity have previously been described in midlife women, with the lowest concentrations observed among African American and Hispanic individuals and the highest among those of Chinese and Japanese ethnicity (39). Other factors that have previously been described to be associated with DHEA-S include metabolic syndrome and functional status (40).

Our results suggest that low levels of DHEA-S were associated with subclinical myocardial injury, HF hospitalization, and death. The inverse relationships between DHEA-S level and atherosclerosis, CHD, and mortality, particularly in men, are well described (6, 7, 41). However, data on the relationship between DHEA-S and subclinical myocardial injury and HF are much more limited. Our results support previous work from the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis cohort, in which DHEA level (DHEA-S was not assessed) was inversely associated with cardiac biomarkers in men and women as well as increased risk for HF with reduced ejection fraction in women (9, 42, 43). We add to the existing body of evidence by showing a relationship between very low DHEA-S level and increased risk for HF hospitalization in men as well as the association between changes in DHEA-S level over time and HF hospitalization. Importantly, instead of a gradual increase in risk with decreasing DHEA-S levels, the association between DHEA-S with HF and mortality appears to be nonlinear. The shape of the spline analyses suggests a threshold below which very low levels of DHEA-S are associated with increased risk for HF and mortality, but higher levels are not associated with further decreased risk for adverse events. This relationship with DHEA-S may not be applicable to other CVD types. For instance, we did not observe a significant association between very low DHEA-S and increased risk of CHD events, an association which has been described in previous studies (7, 13). The discrepancy may be a result of differences in study design, participant characteristics, follow-up time, or other factors. However, it may also reflect the multiple biological activities of DHEA-S and different pathways by which declining DHEA-S may be associated with or contribute to different types of CVD.

Previously, there had been limited understanding of how DHEA/DHEA-S relates to aging and cardiovascular health in older adults. Our study, leveraging the proteomics data from ARIC, begins to shed light on potential mechanisms. Based on results of the IPA, DHEA-S is associated with CVD via a network of proteins/genes including MMP2, secreted frizzled-related protein 1, periostin, collagen alpha 1, and insulin-like growth factor. Many proteins in this network have known functions in organization of extracellular matrix and cardiac remodeling. Age-related disruptions in control of myocardial remodeling have been implicated the development of HF in older adults (44-46). Thus, low DHEA-S levels may predict maladaptive myocardial remodeling and risk for HF in older adults. Whether DHEA-S has direct effect on the extracellular matrix is not clear.

Of the top 5 proteomics hits in our analyses, 3 proteins function in maintaining genetic/epigenetic stability and the other 2 are key factors in adrenal cortical regulation. The most significant proteomic hit observed in our analyses was the positive association of DHEA-S level with RAD51, a highly conserved protein that catalyzes double-strand break DNA repair via homologous recombination (47, 48). A disruption of this mechanism leads to accumulation of double-strand break, increased reliance on more error-prone repair pathways, and ultimately genome instability and cell death (47). RAD51 has been reported to play a role in senescence in both yeast (49) and human (50) cells. Relatedly, DHEA-S levels were noted to have significant negative association with histones. Previous studies have found that increase in circulating histones are associated with cellular stress, apoptosis, and tissue injury (50-53).

Also among the top 5 proteomics hits, POMC and ART are, respectively, the agonist and antagonist peptides of melanocortin receptors. POMC is synthesized in the anterior pituitary gland and is the precursor for several peptide hormones including adrenocorticotropic hormone. ART is primarily expressed in the hypothalamus and plays an important role in appetite stimulation and energy metabolism through antagonism of POMC and its derivatives (54). Though ART does not directly antagonize adrenocorticotropic hormone at the melanocortin 2 receptor, it has been shown to exert inhibitory effects on steroidogenesis via action on melanocortin 4 receptor (55-57). Based on these observations, DHEA-S may be a marker of hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal dysregulation in older age. DHEA-S has been used clinically to aid in the diagnosis of central adrenal insufficiency in patients with pituitary adenomas (58, 59). Similarly, we hypothesize that declining levels of DHEA-S in older age may reflect senescence of the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis, which has been shown to result in decreased levels of DHEA-S and mineralocorticoids and increased levels of glucocorticoids (60). The concept of “adrenopause” has been previously proposed, and additional studies to explore the relationship between adrenal hormones and heart health in older adults are warranted (61). Taken together, low DHEA-S levels likely reflect overall biological age and associated pathological manifestations of aging.

There were several limitations to our study. DHEA-S in ARIC was measured by automated immunoassay, which remains commonly used in the clinical setting. Although mass spectrometry is recognized as the gold standard in the quantification of sex steroid hormones, the concentrations of DHEA-S reached high micromolar concentrations and are several orders of magnitude higher than other steroid hormones, which are in nanomolar concentrations. Therefore, immunoassays are commonly used for DHEA-S quantification, as interference from other steroids is marginal (62). Second, we did not have measurement of DHEA, which is also present in circulation. DHEA has a much higher clearance rate and thus shorter half-life in blood compared with DHEA-S (63). Third, we did not have data on estrone or estradiol, which precluded us from assessing how endogenous estrogen levels may have affected the relationship between DHEA-S and outcome events. Fourth, we did not have hormonal therapy use data in women from visit 5 and thus were not able to adjust for this as a covariate in the visit 5 analysis. However, after publication of the Women’s Health Initiative in 2002, the use of hormonal therapy has dramatically declined; thus, we believe the number of hormonal therapy users at visit 5, when the mean age for women was 75 years, was small, and therefore not adjusting for hormonal therapy use at visit 5 should not impact our results. Fifth, we did not have data on use of systemic and inhaled corticosteroid therapy, which can alter DHEA-S levels (64). Therefore, we cannot discount the effect of disease for which these therapies are used on the association between DHEA-S and CVD. Additional limitations include residual confounding, attrition, and survival bias.

Our study also had several strengths. ARIC is a large established cohort with long follow-up and rigorous adjudication of outcome events. We further used 2 separate time points (visits 4 and 5), which allowed us to assess the relationship of change in DHEA-S level over time and CVD. Finally, the availability of robust proteomics data allowed for consideration of potential mechanistic relationships of DHEA-S.

Conclusions

Among older adults without known CVD, DHEA-S levels generally decline with advancing age, but the degree of change can be quite heterogeneous. Low DHEA-S was associated with increased risk for subclinical myocardial injury, HF hospitalization, and death. DHEA-S is likely a marker of overall biological age and associated pathological manifestations of aging. The identified proteins/genes and networks associated with DHEA-S in our study may help to guide future studies on molecular mechanisms of associations among DHEA-S level, aging, and CVD.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the staff and participants of the ARIC study for their important contributions.

Financial Support: The Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities study has been funded in whole or in part with federal funds from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, National Institutes of Health, Department of Health and Human Services, under Contract nos. (HHSN268201700001I, HHSN268201700002I, HHSN268201700003I, HHSN268201700005I, HHSN2682017 00004I). V.N. was supported by VA MERIT grant. B.Y. was supported by the American Heart Association (17SDG33661228). E.S. was supported by R01-DK089174. E.S. and C.M.B. were supported by R01-HL134320.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- ARIC

Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities

- ART

agouti-related protein

- BMI

body mass index

- CHD

coronary heart disease

- CI

confidence interval

- CVD

cardiovascular disease

- DHEA

dehydroepiandrosterone

- DHEA-S

dehydroepiandrosterone-sulfate

- eGFR

estimated glomerular filtration rate

- HDL-C

high-density lipoprotein cholesterol

- HF

heart failure

- HR

hazard ratio

- ICD-9

International Classification of Diseases 9th edition

- IPA

Ingenuity Pathway Analysis

- MI

myocardial infarction

- MMP-2

matrix metalloproteinase 2

- NT-proBNP

N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide

- POMC

pro-opiomelanocortin

- SBP

systolic blood pressure

- SHBG

sex hormone–binding globulin

Additional Information

Disclosure Summary: R.C.H. reports grant support and consulting fees from Denka Seiken outside the submitted work. V.N. was a site PI for a study sponsored by Merck. S.S.V. reports grants/research support from the Department of Veterans Affairs, World Heart Federation; honorarium from the American College of Cardiology (Associate editor for Innovations acc.org); and Steering Committee member for the PALM registry at Duke Clinical Research Institute (no financial remuneration). J.A.d.L. reports grant support and consulting income from Roche Diagnostics and Abbott Diagnostics, and consulting income from Ortho Clinical Diagnostics. C.M.B. reports grants/research support (significant; paid to institution) and consultant (modest) from Abbott Diagnostic, Denka Seiken, and Roche Diagnostic.

Data Availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article or in the data repositories listed in References.

References

- 1. Savineau JP, Marthan R, Dumas de la Roque E. Role of DHEA in cardiovascular diseases. Biochem Pharmacol. 2013;85(6):718-726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Labrie F, Bélanger A, Cusan L, Gomez JL, Candas B. Marked decline in serum concentrations of adrenal C19 sex steroid precursors and conjugated androgen metabolites during aging. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1997;82(8):2396-2402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Davison SL, Bell R, Donath S, Montalto JG, Davis SR. Androgen levels in adult females: changes with age, menopause, and oophorectomy. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005;90(7):3847-3853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Davis SR, Bell RJ, Robinson PJ, et al. ; ASPREE Investigator Group . Testosterone and estrone increase from the age of 70 years: findings from the sex hormones in older women study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2019;104(12):6291-6300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Barrett-Connor E, Goodman-Gruen D. Dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate does not predict cardiovascular death in postmenopausal women. The Rancho Bernardo Study. Circulation. 1995;91(6):1757-1760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]