Abstract

Background

Tobacco product packaging is a key part of marketing efforts to make tobacco use appealing. In contrast, large, prominent health warnings are intended to inform individuals about the risks of smoking. In the European Union, since May 2016, the Tobacco Products Directive 2014/40/EU (TPD2) requires tobacco product packages to carry combined health warnings consisting of a picture, a text warning and information on stop smoking services, covering 65% of the front and back of the packages.

Methods

Key measures of warning label effectiveness (salience, cognitive reactions and behavioural reaction) before and after implementation of the TPD2, determinants of warning labels’ effectiveness and country differences were examined in a longitudinal sample of 6011 adult smokers from Germany, Greece, Hungary, Poland, Romania and Spain (EUREST-PLUS Project) using longitudinal Generalized Estimating Equations (GEE) models.

Results

In the pooled sample, the warning labels’ effectiveness increased significantly over time in terms of salience (adjusted OR = 1.18; 95% CI: 1.03–1.35), while cognitive and behavioural reactions did not show clear increases. Generally, among women, more highly educated smokers and less addicted smokers, the effectiveness of warning labels tended to be higher.

Conclusion

We found an increase in salience, but no clear increases for cognitive and behavioural reactions to the new warning labels as required by the TPD2. While it is likely that our study underestimated the impact of the new pictorial warning labels, it provides evidence that health messages on tobacco packaging are more salient when supported by large pictures.

Introduction

Since tobacco advertising is largely banned in traditional media, the tobacco industry increasingly uses new and non-traditional media to spread pro-tobacco messages and images, including tobacco product packages.1 Such packaging is much more than just a casing for a product: it distinguishes a product from numerous similar ones and is used to convey brand identity. As such, it serves as an advertising medium.2 The brand image is one deciding factor for brand selection among new smokers and building brand loyalty.2 Tobacco industry internal documents show that intensive research has been conducted on packaging design, including features such as colours, shapes and design elements.2–4 The colours of the packaging are used to manipulate perceptions of taste, strength and health risks.5,6 For example, cigarettes in brightly coloured packs are rated as milder or even less harmful to health.6 Moreover, special packaging designs with eye-catching colours or specific shapes are used to address specific sub-groups, such as young people or women.7

In contrast, warning labels are an effective means of countering the attractiveness of tobacco products. They have been shown to improve smokers’ knowledge of the health risks of smoking, counteract misleading messaging and brand imagery, prevent smoking initiation, motivate smoking cessation and protect ex-smokers from relapsing.8–10 Furthermore, larger and combined warnings comprised of both images and text have been shown to be more effective than plain textual warnings.11,12 Compared with other communication tools such as mass media advertising, health warnings are also a highly cost-effective public health intervention.13

As of November 2002, the European Union (EU) Tobacco Products Directive 2001/37/EC (TPD1) required textual health warnings covering no less than 30% of the front of the pack, and no less than 40% of the back of the pack.14 In place of the textual warnings on the back of the pack, EU member states (MS) could also make pictorial warnings compulsory.15 Since May 2016, in order to further implement the regulations of the World Health Organization Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (WHO FCTC),16,17 the Tobacco Products Directive 2014/40/EU (TPD2) has required tobacco product packages to carry combined health warnings consisting of a picture, a text warning and information on stop smoking services, covering the top 65% of the front and back of the packages.18

The objective of this study was to assess if the implementation of the TPD2 impacted key measures of warning label effectiveness (salience, cognitive reactions and behavioural reaction) in a longitudinal sample of smokers from six EU MS (Germany, Greece, Hungary, Poland, Romania and Spain). Secondary objectives were to explore determinants of warning labels’ effectiveness and to examine country differences.

Methods

Study design

This study was conducted within the context of the European Commission Horizon-2020 funded project entitled European Regulatory Science on Tobacco: Policy implementation to reduce lung diseases (EUREST-PLUS).19 EUREST-PLUS involved the creation of an International Tobacco Control Policy Evaluation Project (ITC Project) cohort of adult smokers in six EU MS (Germany, Greece, Hungary, Poland, Romania and Spain) designed to assess the implementation of the TPD2 and the WHO FCTC at the European level. The conceptual model of the ITC Project is based on a theory-driven framework which hypothesizes the mediational pathways of tobacco control policies on tobacco use behaviours.20 Data from Waves 1 and 2 of the ITC 6 European Country (ITC 6E) Survey were used for this study.

Data collection

The ITC 6E Wave 1 (W1) sample, collected between 16 June 2016 and 12 September 2016, was comprised of 6011 nationally representative cigarette smokers aged 18 or older (about 1000 in each of the six countries). Wave 2 (W2) was conducted after the TPD2 implementation from 12 February 2018 to 6 May 2018 and was comprised of 6027 smokers and recent quitters, including both W1 survey respondents who were successfully re-contacted (n = 3195) and newly recruited adult smokers (n = 2832) to replenish those who were not successfully re-contacted. The W2 retention rates were 71% in Germany, 41% in Greece, 36% in Hungary, 48% in Poland, 54% in Romania and 70% in Spain, with an overall retention rate of 53%.

Participants were sampled from geographic strata according to the Classification of Territorial Units for Statistics (NUTS) crossed with degree of urbanization (urban, intermediate and rural). Approximately 100 area clusters were sampled in each country, which was allocated to strata proportionally to the adult population size. Within each cluster, household addresses were sampled using a random walk design. Where possible, one randomly selected male smoker and one randomly selected female smoker were chosen for an interview from each sampled household. Screening of households continued until the required number of smokers from the cluster had been interviewed. All interviews were conducted face-to-face using tablets (Computer Assisted Personal Interview, CAPI). Further details can be found elsewhere.20–23

Study ethics procedures

The study was approved by the Research Ethics Board of the University of Waterloo, Ontario, Canada and by local ethics boards within study countries. Participation in the study was contingent on provision of individual informed consent, which was obtained either in written or verbal form according to local ethical requirements.

Measures

The questionnaires included relevant socio-demographic measures, such as sex, age, marital status, education and degree of urbanization. Age was categorized into four groups (18–24, 25–39, 40–54 and 55 years and older). Marital status was classified into two groups (not married, widowed, divorced or separated, vs. not married but living together, married or registered partners). In each country, education responses were reclassified to match International Standard Classification of Education (ISCED) coding, which was, in turn, categorized into low (pre-primary, primary, lower secondary), moderate (upper secondary, post-secondary non-tertiary, short-cycle tertiary) and high (bachelor or equivalent, master or equivalent, doctoral or equivalent).

The number of cigarettes smoked per day (CPD) and self-reported time to the first cigarette of the day (TTF) were used to create the Heaviness of Smoking Index (HSI),24 a measure of cigarette dependence. CPD was categorized as ‘0 = 1–10’, ‘1 = 11–20’, ‘2 = 21–30’ and ‘3 = 31 or more cigarettes’, while the categories of TTF were categorized as ‘0 = more than 60 minutes’, ‘1 = 31–60 minutes’, ‘2 = 6–30 minutes’ and ‘3 = 5 minutes or less’. The HSI was calculated by summing the value of the categorical CPD and categorical TTF, both having category values from 0 to 3, giving a score ranging from 0 to 6. The HSI was subsequently categorized into three groups for analysis (0–1: low, 2–4: moderate, 5–6: high).

Four questions were asked of all respondents as indicators of the effectiveness of warning labels: (i) ‘In the last 30 days, how often have you noticed the warning labels on cigarette packages or on roll-your-own packs?’ (‘salience'; responses were classified into ‘very often, often, sometimes’ vs. ‘rarely, never’); (ii) ‘To what extent do the warning labels make you think about the health risks of smoking?’ (cognitive reaction: ‘harm'; responses were classified into ‘a lot, somewhat, a little’ vs. ‘not at all’); (iii) ‘To what extent do the warning labels on cigarette packs make you more likely to quit smoking?’ (cognitive reaction: ‘quitting'; responses were classified into ‘a lot, somewhat, a little’ vs. ‘not at all’); and (iv) ‘In the last 30 days, have the warning labels stopped you from having a cigarette when you were about to smoke one?’ (behavioural reaction: ‘forgoing'; responses were classified into ‘many times, a few times, once’ vs. ‘never’).

Statistical analysis

Only smokers were included in the analyses (N = 6011 in W1, N = 5612 in W2). Prevalence of ‘salience’, ‘harm’, ‘quitting’ and ‘forgoing’ was reported for each country based on cross-sectional data from W1 and W2. To examine changes in the effectiveness of warning labels over time as well as associations with the socio-demographic and smoking-related variables of interest, Generalized Estimating Equations (GEE) models were computed, allowing the analysis of data from individuals across multiple waves. Separate models pooling the responses from all six countries were fitted for each of the four dichotomized indicators of warning label effectiveness using the following specifications: binomial distribution, logit link and exchangeable correlation structure. A variable denoting survey wave was included to estimate the change between waves for each indicator. All GEE models included time-invariant measures assessed at each respondent’s first interview (sex, age group, education, marital status, degree of urbanization, country) as well as the HSI as a time-varying measure assessed at each wave. Country-specific models were also estimated to obtain country-specific estimates of change between waves for each indicator. All statistical tests were two-sided, with an alpha level of 0.05. SAS v9.4 was used for descriptive analyses, and SAS-callable SUDAAN (Version 11.0.3) for GEE models to account for the complex sampling design, longitudinal sampling weights and repeated measures.22,23

Results

Across the six EU countries, the majority of participants were male, middle aged, of low or moderate educational level, living with a partner and living in an urban area. Smokers from Greece had the highest average levels of nicotine dependence (HSI = 3.0 at both waves), while this was lowest in Spain (HSI = 2.3 in W1 and 2.2 in W2). A detailed overview of the distribution of socio-demographic and smoking-related characteristics of the cross-sectional and longitudinal samples can be found in Supplementary table S1.

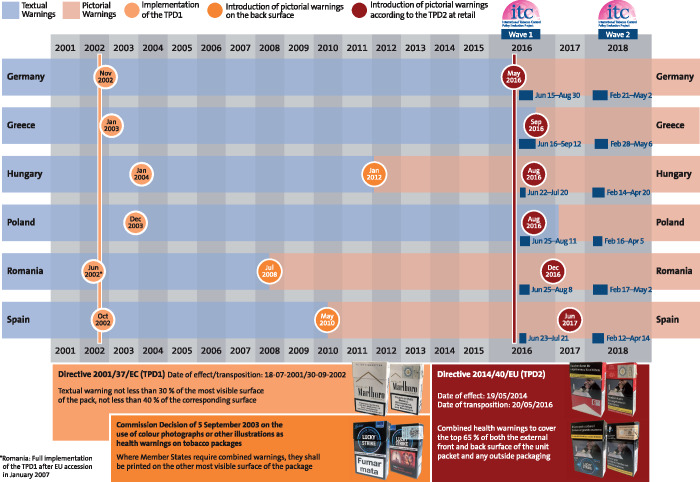

At the time of W1, two countries (Greece and Poland) had text-only warnings in accordance with TPD1, three countries (Hungary, Romania and Spain) required additional combined warnings on the back of the pack, while in Germany the TPD2 had just been implemented and packs with the new pictorial 65% warnings were increasingly penetrating the market. At the time of W2, all six countries had introduced combined pictorial 65% warnings in accordance with TPD2 (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Survey periods and timing of the introduction of health warnings on tobacco packages in accordance with the Tobacco Products Directives (TPD) 1 and 2 by country

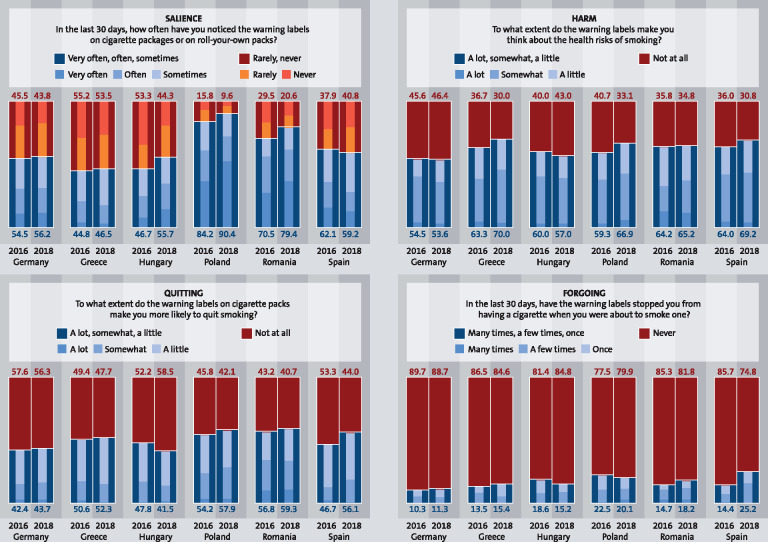

The cross-sectional prevalences of having noticed warning labels (‘salience'), thinking about the health risks of smoking (‘harm'), wanting to quit (‘quitting') and stopping oneself from having a cigarette (‘forgoing') due to the warning labels by country and wave are presented in figure 2. The percentage of respondents who had noticed warning labels at least sometimes in the last 30 days varied widely: it was highest in Poland (W1: 84.2%, W2: 90.4%) and lowest in Greece (W1: 44.8% and W2: 46.5). Over half of respondents in all countries reported that the warning labels had prompted thoughts of the health risks of smoking, with the highest proportion in Greece (W1: 63.3%, W2: 70.0%) and the lowest in Germany (W1: 54.5%, W2: 53.6%). Reporting that the warning labels had made them more likely to want to quit was also frequent, with prevalence ranging from 56.8% and 59.3% in Romania to 42.4% and 43.7% in Germany at W1 and W2, respectively. The prevalence of ‘forgoing' was substantially lower than the other indicators in all countries, ranging from 22.5% and 20.1% in Poland to 10.3% and 11.3% in Germany. All four indicators tended to increase over time, although in some cases for some countries minor declines were observed, none of which reached statistical significance.

Figure 2.

Prevalence of having noticed warning labels (salience), thinking about the health risks of smoking (harm), wanting to quit (quitting) and being stopped from having a cigarette (forgoing) due to warning labels by survey wave; cross-sectional data

Table 1 shows the results of GEE models estimating the association of ‘salience’, ‘harm’, ‘quitting’ and ‘forgoing’ with socio-demographic factors, nicotine dependence (heaviness of smoking), country and survey wave. For most of the associations, patterns were consistent across the four indicators of the effectiveness of warning labels. Effectiveness of warning labels was lower among men, with statistically significant differences for all indicators except ‘forgoing'. No consistent effects for age, degree of urbanization or marital status were observed. The warnings tended to be more effective among higher-educated smokers, with the difference statistically significant for ‘harm' and ‘quitting'. A clear gradient was observed for nicotine dependence for all indicators except for ‘salience', with each significantly higher (about twice as high) among smokers with moderate or low nicotine dependence. In Poland and Romania, the prevalence of ‘salience' was significantly higher compared with Spain (reference category). Similarly, the prevalence of ‘quitting' in Romania was significantly higher compared with Spain, while ‘salience' was significantly lower in Greece and Hungary (relative to Spain). Germany consistently showed low prevalence rates for all indicators. The warning labels tended to have greater overall effectiveness from W1 to W2 with the exception of ‘quitting', though the increase was only statistically significant for ‘salience' [adjusted odds ratio (aOR) = 1.18, 95% CI: 1.03–1.35].

Table 1.

Results of GEE models estimating the association of having noticed warning labels (salience), thinking about health risks (harm), wanting to quit (quitting) and being stopped from having a cigarette (forgoing) due to warning labels with socio-demographic factors, heaviness of smoking, country and survey wave (2016/2018); longitudinal aOR are presented

| Salience | Harm | Quitting | Forgoing | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N (Number of observations used) | 10 884 | 10814 | 10762 | 10813 | |||||

| N (Number of individuals included) | 8390 | 8342 | 8320 | 8351 | |||||

| Events | 6788 | 6709 | 5382 | 1743 | |||||

| aOR | (95% CI) | aOR | (95% CI) | aOR | (95% CI) | aOR | (95% CI) | ||

| Gender | Female (Ref.) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||

| Male | 0.85 | (0.77–0.94) | 0.82 | (0.75–0.90) | 0.86 | (0.78–0.94) | 0.93 | (0.82–1.05) | |

| Age group | 18–24 (Ref.) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||

| 25–39 | 1.14 | (0.93–1.41) | 1.04 | (0.85–1.26) | 0.91 | (0.75–1.11) | 0.82 | (0.64–1.04) | |

| 40–54 | 0.99 | (0.82–1.21) | 1.13 | (0.93–1.37) | 0.98 | (0.82–1.18) | 0.81 | (0.64–1.02) | |

| 55+ | 1.14 | (0.92–1.40) | 1.05 | (0.85–1.28) | 0.88 | (0.72–1.07) | 0.78 | (0.61–1.00) | |

| Education | Low (Ref.) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||

| Moderate | 1.11 | (0.97–1.26) | 1.24 | (1.09–1.41) | 1.32 | (1.18–1.48) | 1.15 | (0.97–1.37) | |

| High | 1.14 | (0.93–1.40) | 1.29 | (1.05–1.58) | 1.41 | (1.17–1.70) | 1.13 | (0.87–1.46) | |

| Marital status | Not married (Ref.) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||

| Married/living with partner | 0.95 | (0.85–1.05) | 1.04 | (0.93–1.17) | 1.15 | (1.02–1.28) | 1.07 | (0.92–1.25) | |

| Degree of urbanisation | Rural (Ref.) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||

| Intermediate | 1.12 | (0.89–1.41) | 1.02 | (0.84–1.25) | 1.08 | (0.92–1.37) | 1.01 | (0.79–1.29) | |

| Urban | 1.04 | (0.85–1.27 | 1.06 | (0.87–1.29) | 1.12 | (0.92–1.37) | 1.01 | (0.77–1.32) | |

| HSI | High (5–6) (Ref.) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||

| Moderate (2–4) | 1.02 | (0.84–1.23) | 1.80 | (1.49–2.16) | 1.92 | (1.58–2.33) | 2.00 | (1.50–2.67) | |

| Low (0–1) | 1.18 | (0.93–1.50) | 2.11 | (1.70–2.61) | 2.37 | (1.90–2.97) | 2.72 | (2.01–3.69) | |

| Country | Spain (Ref.) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||

| Germany | 0.83 | (0.65–1.05) | 0.59 | (0.44–0.77) | 0.76 | (0.58–1.01) | 0.47 | (0.31–0.72) | |

| Greece | 0.53 | (0.41–0.68) | 1.10 | (0.83–1.45) | 1.18 | (0.90–1.54) | 0.79 | (0.56–1.12) | |

| Hungary | 0.72 | (0.56–0.94) | 0.81 | (0.62 to1.07) | 0.97 | (0.74–1.27) | 0.99 | (0.69–1.44) | |

| Poland | 4.40 | (3.34–5.80) | 0.84 | (0.65–1.08) | 1.27 | (0.96–1.68) | 1.15 | (0.82–1.63) | |

| Romania | 2.05 | (1.60–2.64) | 0.95 | (0.74–1.21) | 1.45 | (1.12–1.86) | 0.83 | (0.59–1.16) | |

| Wave | 1 (Ref.) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||

| 2 | 1.18 | (1.03–1.35) | 1.11 | (0.99–1.25) | 1.02 | (0.90–1.16) | 1.11 | (0.93–1.32) | |

Odds ratios adjusted for all covariates listed in the table/HSI: Heaviness of Smoking Index; ranges from 0 to 6; calculated by summing the value of the categorical cigarettes per day and categorical time to first cigarette, both having category values from 0 to 3.

Table 2 presents the results of separate adjusted GEE models for each country estimating the change in each indicator from W1 to W2. In all countries except Spain, ‘salience' tended to be greater in W2 than at W1, with this increase shown to be statistically significant in Hungary, Poland and Romania (aORs of 1.43, 1.58 and 1.50, respectively). For ‘harm', statistically non-significant increases were seen in Greece, Poland and Spain with aORs of 1.33, 1.34 and 1.17, respectively, and a non-significant decrease was seen in Hungary. Minor non-significant increases in ‘quitting' were found in all countries except Hungary, where a non-significant decrease was observed (aOR = 0.74). Effect estimates varied between countries for ‘forgoing', with a statistically significant increase observed in Spain (aOR = 1.72) and non-significant decreases observed in Hungary and Poland.

Table 2.

Results of GEE models estimating the change between survey waves (2016/2018) for having noticed warning labels (salience), thinking about health risks (harm), wanting to quit (quitting) and being stopped from having a cigarette (forgoing) due to warning labels by country; longitudinal aOR are presented

| Salience |

Harm |

Quitting |

Forgoing |

|||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Events | aOR | (95% CI) | N | Events | aOR | (95% CI) | N | Events | aOR | (95% CI) | N | Events | aOR | (95% CI) | |

| Germany | ||||||||||||||||

| W2 vs. W1 | 1711 | 946 | 1.10 | (0.79–1.53) | 1713 | 900 | 1.01 | (0.81–1.26) | 1711 | 693 | 1.10 | (0.90–1.34) | 1713 | 161 | 1.05 | (0.74–1.49) |

| Greece | ||||||||||||||||

| W2 vs. W1 | 1892 | 875 | 1.07 | (0.72–1.58) | 1893 | 1269 | 1.33 | (0.93–1.91) | 1893 | 969 | 1.06 | (0.74–1.53) | 1892 | 268 | 1.20 | (0.80–1.80) |

| Hungary | ||||||||||||||||

| W2 vs. W1 | 1893 | 984 | 1.43 | (1.05–1.96) | 1875 | 1093 | 0.86 | (0.64–1.15) | 1872 | 835 | 0.74 | (0.52–1.06) | 1879 | 323 | 0.78 | (0.47–1.31) |

| Poland | ||||||||||||||||

| W2 vs. W1 | 1745 | 1516 | 1.58 | (1.06–2.36) | 1720 | 1109 | 1.34 | (0.96–1.88) | 1716 | 985 | 1.11 | (0.82–1.50) | 1710 | 359 | 0.81 | (0.53–1.24) |

| Romania | ||||||||||||||||

| W2 vs. W1 | 1819 | 1351 | 1.50 | (1.12–2.03) | 1799 | 1178 | 1.04 | (0.84–1.28) | 1791 | 1052 | 1.03 | (0.80–1.32) | 1813 | 298 | 1.30 | (0.86–1.97) |

| Spain | ||||||||||||||||

| W2 vs. W1 | 1824 | 1116 | 0.82 | (0.62–1.08) | 1814 | 1160 | 1.17 | (0.90–1.54) | 1779 | 848 | 1.14 | (0.79–1.64) | 1806 | 334 | 1.72 | (1.14–2.60) |

N, number of observations used; W1, Wave 1; W2, Wave 2; odds ratios adjusted for gender, age group, education, marital status, degree of urbanization and heaviness of smoking index.

Discussion

This study examined changes in key measures of warning label effectiveness among smokers from six EU MS before and after implementation of the new pictorial tobacco warning labels as required by the TPD2. We found that salience of the new warning labels increased significantly between waves in the pooled sample, while no clear trends were seen for self-reported cognitive and behavioural reactions. The effectiveness of warning labels generally tended to be higher among women, more highly educated smokers and less addicted smokers.

In all countries, the appearance of the warnings changed between the two study periods, with the greatest differences observed in Germany, Poland and Greece, where from pre- to post-TPD2 the warning labels changed from textual warnings to large combined pictorial warnings on both sides of the pack. In Germany, however, the combined warnings in accordance with TPD2 were introduced several weeks before the first survey period. Although full market penetration took several months due to stockpiling of old packs, it is highly likely that the pictorial warnings were known to at least some respondents present within the W1-survey, as it had been a publicly debated topic and their novelty attracted increased attention. In Hungary, Romania and Spain, pictorial warnings had been required on the back of cigarette packaging for at least 4 years prior to W1. Therefore, the changes between waves included the additional presence of pictures on the front surface of the pack, as well as the increased size of the combined warnings (going from 30% to 65%).

Some of this study’s findings are consistent with expected changes as a result of the implementation of the new requirements for pictorial warning labels due to TPD2. For example, the clearest increase in the effectiveness of the warnings in terms of the frequency of noticing warning labels and thinking about the health risks of smoking was found in Poland, which changed from text-only to pictorial labels. However, although there were comparable changes in the appearance of the warning labels in Hungary, Romania and Spain, ‘salience' increased significantly only in Hungary and Romania; similar trends were not observed in Spain. Of the cognitive and behavioural reactions expected to be prompted by the introduction of the combined warnings, only one of 18 was found to be statistically significant (the behavioural reaction of ‘forgoing’ in Spain), a rate similar to that expected by chance.

In contrast to our findings, previous studies using ITC Project data have found a marked increase in warning label effectiveness after the implementation of pictorial warning labels, such as in Australia, Thailand and Mauritius.25–27 However, an ITC study on the effectiveness of EU warning labels found increases in effectiveness ratings in the UK, but mostly declines in France after both countries had changed from textual to pictorial warning labels in 2008 and 2010, respectively.28 This is similar to our study, which also did not find consistent increases in warning label effectiveness ratings after implementation of TPD2-compliant pictorial warning labels in EU MS.

We can only speculate why we did not find the expected increases in the measures of warning label effectiveness. It is possible that other factors, such as the overall tobacco control environment in a country, influence the extent to which warning labels are effective. For example, it is striking that effectiveness tended to be lowest at W1 and to increase the least in Germany and Greece, which are ranked among the most inactive countries with regards to their tobacco control policies, while effectiveness was greater and increased more over time in Poland, a much higher-ranked country, despite having the same warning labels at both pre- and post-TPD2.29 Another potential explanation for why increases appeared to be lower than expected could be wear-out effects. Previous studies have found that warning label effectiveness declines over time25,28,30 and it is possible that in our study, in which post-TPD2 evaluations of warning labels took place more than a year after their implementation in all countries but Spain, some increases were not captured due to wear-out of the new warning labels. While wear-out effects may be mitigated by the TPD2 requirement for three sets of annually rotating warnings, it remains possible that our study underestimated the impact of the new TPD2 pictorial health warnings. Furthermore, it is important to keep in mind that this study only included smokers, meaning that former smokers who had quit in response to the new pictorial health warnings were not included in the W2-survey post-TPD2. This may also have led to an underestimation of the impact of warning labels.

Some further limitations of this study need to be considered. First, our indicators of warning label effectiveness are self-reported reactions to warning labels and are thus subject to misclassification (e.g. due to social desirability bias). Second, sample attrition might also have affected the results and—given the different retention rates—might have hampered comparison between countries. While there is some potential for selection bias, we believe that such bias is limited through the replenishment of the sample with newly recruited respondents. Third, no data were available from a comparable European country which could have served as a control, making it difficult to distinguish between the impact of the TPD2, secular trends and wear-out effects. Finally, even though the study extends our understanding of the real-world effectiveness of warning labels by employing cross-country comparisons in large samples based on harmonized methods and measures, the observational nature of the study does not allow for drawing causal conclusions.

In addition to the combined health warnings evaluated in this study, the TPD2 allows EU MS to introduce further measures relating to standardization of tobacco product packaging or plain packaging to prohibit any branding. Plain packaging has been or will be implemented in five MS, including France (since 2016), the UK (since 2016), Ireland (since 2017), Hungary (since 2018) and Slovenia (from 2020).31 Further monitoring is warranted to understand the cognitive and behavioural impacts of such measures as well as trends and wear-out effects.

Conclusions

In terms of the indicators examined within this study, pictorial health warnings in accordance with TPD2 were found to be more salient than plain text warnings and back-only pictorial warnings in accordance with TPD1. No declines, but also no clear increases were observed for the three cognitive and behavioural reactions we evaluated, but as discussed above it is likely that our study underestimated the impact of the new pictorial warning labels. In conclusion, this study provides evidence that the pictorial warning labels as required by the TPD2 have increased the salience of health warning messages and that the magnitude of this effect differs across countries. Further monitoring of warning label effectiveness is warranted to understand their behavioural impact as well as possible wear-out effects.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

EUREST-PLUS Consortium

European Network on Smoking and Tobacco Prevention (ENSP), Belgium: Constantine I. Vardavas, Andrea Glahn, Christina N. Kyriakos, Dominick Nguyen, Katerina Nikitara, Cornel Radu-Loghin, Polina Starchenko; University of Crete (UOC), Greece: Aristidis Tsatsakis, Charis Girvalaki, Chryssi Igoumenaki, Sophia Papadakis, Aikaterini Papathanasaki, Manolis Tzatzarakis, Alexander I. Vardavas; Kantar Public, Belgium: Nicolas Bécuwe, Lavinia Deaconu, Sophie Goudet, Christopher Hanley, Oscar Rivière; Smoking or Health Hungarian Foundation (SHHF), Hungary: Tibor Demjén, Judit Kiss, Anna Piroska Kovacs; Catalan Institut of Oncology (ICO), Spain: Esteve Fernández, Yolanda Castellano, Marcela Fu, Sarah O. Nogueira, Olena Tigova; King’s College London (KCL), United Kingdom: Ann McNeill, Katherine East, Sara C. Hitchman; Cancer Prevention Unit and WHO Collaborating Centre for Tobacco Control, German Cancer Research Center (DKFZ), Germany: Ute Mons, Sarah Kahnert; National and Kapodistrian University of Athens (UoA), Greece: Yannis Tountas, Panagiotis Behrakis, Filippos T. Filippidis, Christina Gratziou, Paraskevi Katsaounou, Theodosia Peleki, Ioanna Petroulia, Chara Tzavara; Aer Pur Romania, Romania: Antigona Carmen Trofor, Marius Eremia, Lucia Lotrean, Florin Mihaltan; European Respiratory Society (ERS), Switzerland: Gernot Rohde, Tamaki Asano, Claudia Cichon, Amy Far, Céline Genton, Melanie Jessner, Linnea Hedman, Christer Janson, Ann Lindberg, Beth Maguire, Sofia Ravara, Valérie Vaccaro, Brian Ward; Maastricht University, the Netherlands: Marc Willemsen, Hein de Vries, Karin Hummel, Gera E. Nagelhout; Health Promotion Foundation (HPF), Poland: Witold A. Zatoński, Aleksandra Herbeć, Kinga Janik-Koncewicz, Krzysztof Przewoźniak, Mateusz Zatoński; University of Waterloo (UW), Canada: Geoffrey T. Fong, Thomas K. Agar, Pete Driezen, Shannon Gravely, Anne C. K. Quah, Mary E. Thompson.

Funding

The EUREST-PLUS project has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under grant agreement No 681109 (CIV) and the University of Waterloo (GTF). Additional support was provided to the University of Waterloo by a foundation grant from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (FDN148477). S.K. is supported by the German Federal Ministry of Health. G.T.F. was supported by a Senior Investigator Grant from the Ontario Institute for Cancer Research. E.F. is partly supported by Ministry of Universities and Research, Government of Catalonia (2017SGR319) and by the Instituto Carlos III and co-funded by the European Regional Development Fund (FEDER) (INT16/00211 and INT17/00103), Government of Spain. E.F. thanks CERCA Programme Generalitat de Catalunya for the institutional support to IDIBELL.

Conflicts of interest: The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript or in the decision to publish the results. G.T.F. has served as an expert witness on behalf of governments in litigation involving the tobacco industry. K.P. reports grants and personal fees from the Polish League Against Cancer, outside the submitted work.

Key points

The Tobacco Products Directive 2014/40/EU (TPD2) requires tobacco product packages to carry pictorial warning labels, covering the top 65% of the front and back of the packages.

This study aimed to examine changes in key measures of warning label effectiveness after implementation of the new TPD2 pictorial tobacco warning labels among smokers from six EU MS.

We found that salience of the new warning labels increased significantly, while no clear increases were found for self-reported cognitive and behavioural responses.

Our study provides evidence that the pictorial warning labels as required by the TPD2 have increased the salience of the health warning messages.

Contributor Information

the EUREST-PLUS Consortium:

Constantine I Vardavas, Andrea Glahn, Christina N Kyriakos, Dominick Nguyen, Katerina Nikitara, Cornel Radu-Loghin, Polina Starchenko, Aristidis Tsatsakis, Charis Girvalaki, Chryssi Igoumenaki, Sophia Papadakis, Aikaterini Papathanasaki, Manolis Tzatzarakis, Alexander I Vardavas, Nicolas Bécuwe, Lavinia Deaconu, Sophie Goudet, Christopher Hanley, Oscar Rivière, Tibor Demjén, Judit Kiss, Anna Piroska Kovacs, Esteve Fernández, Yolanda Castellano, Marcela Fu, Sarah O Nogueira, Olena Tigova, Ann McNeill, Katherine East, Sara C Hitchman, Ute Mons, Sarah Kahnert, Yannis Tountas, Panagiotis Behrakis, Filippos T Filippidis, Christina Gratziou, Paraskevi Katsaounou, Theodosia Peleki, Ioanna Petroulia, Chara Tzavara, Antigona Carmen Trofor, Marius Eremia, Lucia Lotrean, Florin Mihaltan, Gernot Rohde, Tamaki Asano, Claudia Cichon, Amy Far, Céline Genton, Melanie Jessner, Linnea Hedman, Christer Janson, Ann Lindberg, Beth Maguire, Sofia Ravara, Valérie Vaccaro, Brian Ward, Marc Willemsen, Hein de Vries, Karin Hummel, Gera E Nagelhout, Witold A Zatoński, Aleksandra Herbeć, Kinga Janik-Koncewicz, Krzysztof Przewoźniak, Mateusz Zatoński, Geoffrey T Fong, Thomas K Agar, Pete Driezen, Shannon Gravely, Anne C K Quah, and Mary E Thompson

References

- 1.National Cancer Institute. The Role of the Media in Promoting and Reducing Tobacco Use. Bethesda, Maryland: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Wakefield M, Morley C, Horan JK, Cummings KM. The cigarette pack as image: new evidence from tobacco industry documents. Tob Control 2002;11: I73–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Difranza JR, Clark DM, Pollay RW. Cigarette package design: opportunities for disease prevention. Tob Induced Dis 2003;1:97–109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Kotnowski K, Hammond D. The impact of cigarette pack shape, size and opening: evidence from tobacco company documents. Addiction 2013;108:1658–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Lempert LK, Glantz S. Packaging colour research by tobacco companies: the pack as a product characteristic. Tob Control 2017;26:307–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Hammond D, Parkinson C. The impact of cigarette package design on perceptions of risk. J Public Health (Oxf) 2009;31:345–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Preventing Tobacco Use among Youth and Young Adults: A Report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta, Georgia: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hammond D. Tobacco Labelling & Packaging Toolkit. A Guide to FCTC Article 11. Waterloo, Canada: Department of Health Studies, University of Waterloo, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Hammond D, Fong GT, Borland R, et al. Text and graphic warnings on cigarette packages: findings from the international tobacco control four country study. Am J Prev Med 2007;32:202–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Borland R, Yong HH, Wilson N, et al. How reactions to cigarette packet health warnings influence quitting: findings from the ITC four-country survey. Addiction 2009;104:669–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Noar SM, Francis DB, Bridges C, et al. The impact of strengthening cigarette pack warnings: systematic review of longitudinal observational studies. Soc Sci Med 2016;164:118–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ratih SP, Susanna D. Perceived effectiveness of pictorial health warnings on changes in smoking behaviour in Asia: a literature review. BMC Public Health 2018;18:1165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.ITC Project. Health Warnings on Tobacco Packages: ITC Cross-Country Comparison Report. Waterloo, Ontario: University of Waterloo, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 14.European Parliament, European Council. Directive 2001/37/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council on the approximation of the laws, regulations and administrative provisions of the Member States concerning the manufacture, presentation and sale of tobacco products. Off J Eur Union 2001;44:L194/126–L194/134. [Google Scholar]

- 15.European Commission. European Commission decision of 5 September 2003 on the use of colour photographs or other illustrations as health warnings on tobacco packages. Off J Eur Union 2003;46:L226/224–L226/226. [Google Scholar]

- 16.World Health Organization. WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control. Available at: http://www.who.int/fctc/en (25 February 2020, date last accessed).

- 17.WHO FCTC Conference of the Parties. Guidelines for implementation of Article 11: Packaging and labelling of tobacco products. Adopted by the Conference of the Parties at its third session (decision FCTC/COP3(10)), 2008.

- 18.European Parliament, European Council. Directive 2014/40/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council of 3 April 2014 on the approximation of the laws, regulations and administrative provisions of the Member States concerning the manufacture, presentation and sale of tobacco and related products and repealing Directive 2001/37/EC. Off J Eur Union 2014;57:L127/121–L127/138. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Vardavas CI, Bécuwe N, Demjén T , et al. ; on behalf of the EUREST-PLUS consortium. Study Protocol of European Regulatory Science on Tobacco (EUREST-PLUS): policy implementation to reduce lung disease. Tob Induc Dis 2018;16:A2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Fong GT, Thompson ME, Boudreau C, et al. ; on behalf of the EUREST-PLUS consortium The Conceptual Model and Methods of Wave 1 (2016) of the EUREST-PLUS ITC 6 European Countries Survey. Tob Induc Dis 2018;16:A3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Thompson ME, Driezen P, Boudreau C, et al. ; on behalf of the EUREST-PLUS consortium. Methods of the International Tobacco Control (ITC) EUREST-PLUS ITC Europe Surveys. Eur J Public Health 2020;30:iii4–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.ITC Project. ITC 6 European Country Survey Wave 1 Technical Report. 1 February 2017, University of Waterloo, Waterloo, Ontario, Canada, and European Network on Smoking and Tobacco Prevention, Brussels, Belgium, 2017. Available at: https://itcproject.s3.amazonaws.com/uploads/documents/ITC6E_Wave1_Tech.pdf (25 February 2020, date last accessed).

- 23.Available at: ITC Project. ITC 6 European Country Survey Wave 2 Technical Report. 20 February 2019, University of Waterloo, Waterloo, Ontario, Canada, and European Network on Smoking and Tobacco Prevention, Brussels, Belgium, 2019. Available at: https://itcproject.s3.amazonaws.com/uploads/documents/ITC6e_Wave2_Tec.pdf (24 February 2020, date last accessed).

- 24. Heatherton TF, Kozlowski LT, Frecker RC, et al. Measuring the heaviness of smoking: using self-reported time to the first cigarette of the day and number of cigarettes smoked per day. Br J Addict 1989;84:791–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Borland R, Wilson N, Fong GT, et al. Impact of graphic and text warnings on cigarette packs: findings from four countries over five years. Tob Control 2009;18:358–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Yong HH, Fong GT, Driezen P, et al. Adult smokers’ reactions to pictorial health warning labels on cigarette packs in Thailand and moderating effects of type of cigarette smoked: findings from the international tobacco control southeast Asia survey. Nicotine Tob Res 2013;15:1339–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Green AC, Kaai SC, Fong GT, et al. Investigating the effectiveness of pictorial health warnings in Mauritius: findings from the ITC Mauritius survey. Nicotine Tob Res 2014;16:1240–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Nagelhout GE, Willemsen MC, de Vries H, et al. Educational differences in the impact of pictorial cigarette warning labels on smokers: findings from the International Tobacco Control (ITC) Europe surveys. Tob Control 2016;25:325–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Joossens L, Raw M. Tobacco Control Scale. Monitoring the Implementation of Tobacco Control Policies Systematically at Country-Level across Europe. Available at: https://www.tobaccocontrolscale.org (25 February 2020, date last accessed). [Google Scholar]

- 30. Hitchman SC, Driezen P, Logel C, et al. Changes in effectiveness of cigarette health warnings over time in Canada and the United States, 2002-2011. Nicotine Tob Res 2014;16:536–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Canadian Cancer Society. Cigarette Package Health Warnings: International Status Report, Sixth Edition. Toronto, Canada: Canadian Cancer Society, 2018. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.