Abstract

Background

This study presents perceptions of the harmfulness of electronic cigarettes (e-cigarettes) relative to combustible cigarettes among smokers from six European Union (EU) countries, prior to the implementation of the EU Tobacco Products Directive (TPD), and 2 years post-TPD.

Methods

Data were drawn from the EUREST-PLUS ITC Europe Surveys, a cohort study of adult smokers (≥18 years) from Germany, Greece, Hungary, Poland, Romania and Spain. Data were collected in 2016 (pre-TPD: N = 6011) and 2018 (post-TPD: N = 6027). Weighted generalized estimating equations were used to estimate perceptions of the harmfulness of e-cigarettes compared to combustible cigarettes (less harmful, equally harmful, more harmful or ‘don’t know’).

Results

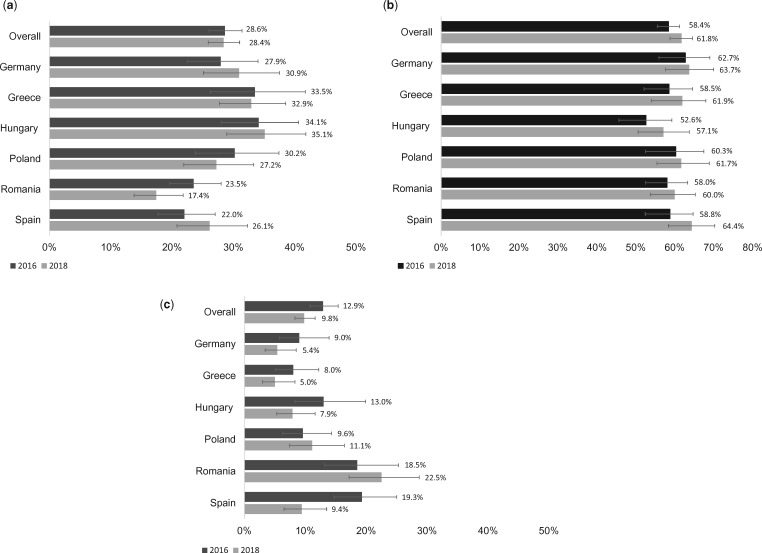

In 2016, among respondents who were aware of e-cigarettes (72.2%), 28.6% reported that they perceived e-cigarettes to be less harmful than cigarettes (range 22.0% in Spain to 34.1% in Hungary). In 2018, 72.2% of respondents were aware of e-cigarettes, of whom 28.4% reported perceiving that e-cigarettes are less harmful. The majority of respondents perceived e-cigarettes to be equally or more harmful than cigarettes in both 2016 (58.5%) and 2018 (61.8%, P > 0.05). Overall, there were no significant changes in the perceptions that e-cigarettes are less, equally or more harmful than cigarettes, but ‘don’t know’ responses significantly decreased from 12.9% to 9.8% (P = 0.036). The only significant change within countries was a decrease in ‘don’t know’ responses in Spain (19.3–9.4%, P = .001).

Conclusions

The majority of respondents in these six EU countries perceived e-cigarettes to be equally or more harmful than combustible cigarettes.

Introduction

Smoked tobacco is the most dangerous form of tobacco consumption.1,2 The smoke from combustible cigarettes, by far the most common form of tobacco use in most countries, includes over 4000 chemicals and at least 70 known carcinogens.1 It is well-established that cigarettes kill a third to half of all people who use them, and those who die from smoking lose over a decade of life.3,4 It has long been known that people smoke tobacco for the nicotine, but die from the poisonous chemicals in tobacco smoke (e.g. hydrogen cyanide, ammonia and high levels of nitrosamines and formaldehyde).1,5

In the past, the tobacco industry developed what they claimed to be ‘safer’ cigarettes in response to smokers’ growing health concerns. Filtered light/low-tar cigarettes were marketed as lower-harm alternatives, but provided no such reduction in harm, mainly because of compensatory smoking behaviours.6 These industry efforts provided smokers with a false sense of reduced risk, and there is epidemiological evidence that they undermined smoking cessation.7

Novel nicotine vaping products, such as electronic cigarettes (e-cigarettes), may have a role to play in reducing the health-related harms of tobacco smoking by assisting cessation attempts and supporting long-term abstinence from smoking. Recent comprehensive reviews of the available scientific evidence by the National Academy of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine (NASEM),8 Public Health England (PHE)9 and the Royal College of Physicians (RCP) London,10 as well as position statements by other bodies11 have concluded that although e-cigarettes contain harmful constituents, overall, they are less harmful than combustible cigarettes.

Despite the scientific evidence that e-cigarettes are less harmful than combustible cigarettes, people’s perceptions of the risks associated with e-cigarette use have been shown to be over-estimated, particularly in recent years, including among smokers who could benefit from them.9,12 Several observational studies have shown the main reasons for smokers using e-cigarettes were as a harm reducing alternative to cigarettes or to help them to quit smoking.13–16 Moreover, the belief that e-cigarettes are less harmful than combustible cigarettes has been shown to be associated with using e-cigarettes during a smoking cessation attempt, in reducing cigarette consumption, and in quitting smoking altogether.12,15,17–20 One recent study from the Population Assessment of Tobacco and Health (PATH) Study in the USA found that adult dual users of e-cigarettes and cigarettes who perceived e-cigarettes to be less harmful than combustible cigarettes were more likely to switch to exclusive e-cigarette use, more likely to remain dual users and less likely to relapse back to exclusive cigarette smoking 1 year later compared to dual users with other perceptions of e-cigarette harm.21 Therefore, inaccurate perceptions of the relative risk of e-cigarettes and combustible cigarettes, particularly among smokers who are unable or unwilling to completely give up nicotine, may deter smokers from switching to using e-cigarettes.

Various countries around the world have taken quite different approaches to the regulation of e-cigarettes. A number of countries have banned e-cigarettes with and/or without nicotine, some countries have not implemented any regulations, while others have regulated nicotine-containing e-cigarettes for consumer safety purposes (e.g. set a minimum age of purchase, restricted use in public places).22 In 2016, the European Union (EU) implemented stronger regulations for e-cigarettes under Article 20 of the EU Tobacco Products Directive (TPD). Some of the key measures that may have impacted harm perceptions for e-cigarettes include: mandated textual health warnings (e.g. ‘This product contains nicotine which is a highly addictive substance’), a ban on promotional and misleading elements on packaging, advertising and promotion bans and some safety and quality requirements (e.g. capped nicotine levels, volume restrictions on tanks and refills, child-resistant refill containers). These changes took place alongside TPD-mandated enhancements to health warnings on tobacco packaging, which became larger (65%) with graphic picture warnings on the front and back.

It is important to monitor harm perceptions, as it can help us to understand changing patterns of product use. It has been shown that stricter e-cigarette regulations influence perceptions about relative e-cigarette and cigarette harm,23 and product regulations may shape or change beliefs about nicotine products. This study aimed to examine perceptions of the harmfulness of e-cigarettes relative to combustible cigarettes in six EU countries at two time-points: first in 2016, prior to the implementation of the TPD, and then again in 2018, after the implementation of the TPD.

Methods

Study design, sample and procedure

The ‘ITC 6 European Country (ITC 6E) Survey’ was undertaken within the context of a European Commission Horizon-2020 funded study ‘(EURESTPLUS- HCO-06-2015)’, which aimed to evaluate the impact of the EU TPD and the World Health Organization (WHO) Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (FCTC).

The ITC 6E Survey is a prospective cohort study of adult smokers (aged ≥18) from six EU Member States: Germany, Greece, Hungary, Poland, Romania and Spain. It was designed to produce nationally representative samples in each of the six countries. Before the implementation of the TPD (pre-TPD, Wave 1: June to September 2016), approximately 1000 adult smokers who reported having smoked at least 100 cigarettes in their lifetime, and smoked at least monthly, were recruited from each country. Respondents were selected from households in urban, intermediate or rural regions, and sampled using a stratified two-stage area sampling design with a random-walk technique. A maximum of two smokers (one male and one female) from each household were eligible to participate. After providing written consent, 6011 respondents completed the survey via a computer-assisted personal interview conducted in each country’s official language. Household response rates ranged from 30% in Germany to 64% in Hungary. The survey took on average 35 min to complete.

Following the implementation of the TPD (post-TPD, Wave 2: February to May 2018), 6027 respondents completed the study. These respondents consisted of two sample types: (i) re-contacted (cohort) respondents (n = 3195) from pre-TPD who were followed up regardless of their current smoking status (retention rates ranged from 36% in Hungary to 71% in Germany and Spain, with an average of 53% for the full sample); and (ii) new respondents (current smokers) to replenish those who were lost to attrition. The replenishment sample (n = 2832) was recruited from newly selected households, and approached in the same manner as pre-TPD, with the random-walk procedure beginning at a new (random) starting point. Within the context of this manuscript, we present the comparison of the entire population at both time points (repeated cross-sectional design).

The study was approved by the Research Ethics Board of the University of Waterloo in Canada, and by local ethics boards in the participating countries. Further details about the study protocol can be found elsewhere.24

Data weighting

After all data were collected and cleaned, each respondent was assigned a sampling weight according to their wave of recruitment. For those present in both 2016 and 2018, the sampling weight was their 2016 wave cross-sectional weight, rescaled to sum to the sample size for each country. For respondents newly recruited in 2018, the sampling weight was based on the cross-sectional weight rescaled to sum to the sample size of the 2018 wave recruits in each country. Weights were calibrated using national surveys from each of the respective countries.

Measurements

Sociodemographic variables

Sociodemographic measures were sex [female versus (vs.) male], age group (18–24, 25–39, 40–54 and ≥55 years), employment status (employed vs. otherwise) and degree of urbanization (urban, intermediate and rural). In each country, household income information was collected in the local currency. Different thresholds were used in each country to classify respondents as low, moderate or high income (Supplementary table S1). Respondents who refused to provide household income were retained for analysis by including an ‘income not reported’ category. Education was also classified as low, moderate or high using the International Standard Classification of Education.

Smoking variables

All respondents were initially recruited as current smokers. Cohort respondents were asked to report their smoking status at the time of the Wave 2 survey and were categorized herein as either a daily smoker, non-daily smoker or ‘quitter’. All respondents at the time of initial recruitment were asked to report: (i) their current frequency of smoking (daily, weekly and monthly); and (ii) number of cigarettes smoked per day (CPD: ≤10, 11–20, 21–30 and ≥31; quitters = 0) which was used as a proxy measure of nicotine dependence.

E-cigarette variables

All respondents were asked to report if they had ever heard of e-cigarettes (‘yes’ or ‘no’, with ‘I don’t know’ responses classified as ‘no’). Those who had heard of e-cigarettes were asked if they had ever tried an e-cigarette (‘yes’ or ‘no’), and if so, if they were currently using one. Responses were: ‘yes’ (daily, weekly, monthly or less than monthly) or ‘not at all’ (‘don’t know’ responses were classified as ‘no’). These were classified herein as ‘currently using an e-cigarette’ vs. ‘currently a non-user’.

Outcome

Perceived harmfulness of e-cigarettes compared to combustible cigarettes: All respondents who were aware of e-cigarettes were asked: ‘In your opinion, is using e-cigarettes or vaping devices less harmful to health, more harmful to health, or no different than smoking ordinary cigarettes?’ Response options were categorized as: ‘less harmful’, ‘equally harmful’, ‘more harmful’ or ‘don’t know’. In addition, for some analyses (and consistent with previous research30), response options were categorized as: more/equally harmful vs. less harmful vs. don’t know. Respondents who did not answer this question were excluded from all analyses.

Statistical analysis

Unweighted statistics were used to describe respondents’ baseline characteristics from each country (table 1).

Table 1.

Unweighted baseline characteristics of smokers present in 2016 and/or 2018

| Germany, n (%) | Greece, n (%) | Hungary, n (%) | Poland, n (%) | Romania, n (%) | Spain, n (%) | Overall, N (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wave of recruitment | |||||||

| 2016 | 635 (75.5) | 737 (61.0) | 679 (60.4) | 685 (67.1) | 679 (73.7) | 851 (76.9) | 4266 (68.6) |

| 2018 | 206 (24.5) | 471 (39.0) | 446 (39.6) | 336 (32.9) | 242 (26.3) | 255 (23.1) | 1956 (31.4) |

| Sex | |||||||

| Female | 427 (50.8) | 568 (47.0) | 535 (47.6) | 551 (54.0) | 371 (40.3) | 502 (45.4) | 2954 (47.5) |

| Male | 414 (49.2) | 640 (53.0) | 590 (52.4) | 470 (46.0) | 550 (59.7) | 604 (54.6) | 3268 (52.5) |

| Average age (SD) | 44.8 (14.5) | 45.3 (13.8) | 44.8 (13.9) | 43.6 (14.2) | 43.3 (14.0) | 42.4 (14.0) | 44.1 (14.1) |

| Age group | |||||||

| 18–24 | 80 (9.5) | 84 (7.0) | 82 (7.3) | 87 (8.5) | 110 (11.9) | 142 (12.8) | 585 (9.4) |

| 25–39 | 244 (29.0) | 340 (28.1) | 341 (30.3) | 368 (36.0) | 270 (29.3) | 334 (30.2) | 1897 (30.5) |

| 40–54 | 282 (33.5) | 474 (39.2) | 400 (35.6) | 289 (28.3) | 306 (33.2) | 388 (35.1) | 2139 (34.4) |

| 55+ | 235 (27.9) | 310 (25.7) | 302 (26.8) | 277 (27.1) | 235 (25.5) | 242 (21.9) | 1601 (25.7) |

| Degree of urbanization | |||||||

| Urban | 296 (35.2) | 210 (17.4) | 390 (34.7) | 377 (36.9) | 316 (34.3) | 595 (53.8) | 2184 (35.1) |

| Intermediate | 344 (40.9) | 710 (58.8) | 436 (38.8) | 317 (31.0) | 234 (25.4) | 377 (34.1) | 2418 (38.9) |

| Rural | 201 (23.9) | 288 (23.8) | 299 (26.6) | 327 (32.0) | 371 (40.3) | 134 (12.1) | 1620 (26.0) |

| Income | |||||||

| Not reported | 107 (12.7) | 237 (19.6) | 390 (34.7) | 332 (32.5) | 90 (9.8) | 4 (40.7) | 1606 (25.8) |

| Low | 252 (30.0) | 184 (15.2) | 164 (14.6) | 140 (13.7) | 157 (17.0) | 279 (25.2) | 1176 (18.9) |

| Moderate | 259 (30.8) | 619 (51.2) | 287 (25.5) | 351 (34.4) | 394 (42.8) | 303 (27.4) | 2213 (35.6) |

| High | 223 (26.5) | 168 (13.9) | 284 (25.2) | 198 (19.4) | 280 (30.4) | 74 (6.7) | 1227 (19.7) |

| Education | |||||||

| Low | 427 (51.0) | 321 (26.6) | 652 (58.1) | 130 (12.9) | 218 (23.9) | 432 (39.1) | 2180 (35.2) |

| Moderate | 339 (40.5) | 639 (52.9) | 388 (34.6) | 757 (75.0) | 596 (65.3) | 575 (52.0) | 3294 (53.2) |

| High | 72 (8.6) | 247 (20.5) | 83 (7.4) | 123 (12.2) | 99 (10.8) | 98 (8.9) | 722 (11.7) |

| Smoking status | |||||||

| Daily smoker | 763 (90.7) | 1175 (97.3) | 1104 (98.1) | 986 (96.6) | 888 (96.4) | 1073 (97.0) | 5989 (96.3) |

| Non-daily smoker | 78 (9.3) | 33 (2.7) | 21 (1.9) | 35 (3.4) | 33 (3.6) | 33 (3.0) | 233 (3.7) |

| Type smoked | |||||||

| FM only | 608 (72.3) | 882 (73.0) | 586 (52.1) | 827 (81.1) | 861 (93.5) | 803 (72.6) | 4567 (73.4) |

| RYO only | 95 (11.3) | 310 (25.7) | 454 (40.4) | 76 (7.5) | 15 (1.6) | 209 (18.9) | 1159 (18.6) |

| Both | 138 (16.4) | 16 (1.3) | 85 (7.6) | 117 (11.5) | 45 (4.9) | 94 (8.5) | 495 (8.0) |

| CPD | |||||||

| <10 | 315 (37.5) | 330 (27.3) | 396 (35.2) | 337 (33.2) | 322 (35.0) | 463 (41.9) | 2163 (34.8) |

| 11–20 | 400 (47.6) | 572 (47.4) | 613 (54.5) | 579 (57.0) | 484 (52.6) | 538 (48.6) | 3186 (51.3) |

| 21–30 | 97 (11.5) | 166 (13.7) | 86 (7.6) | 74 (7.3) | 72 (7.8) | 64 (5.8) | 559 (9.0) |

| 31+ | 28 (3.3) | 140 (11.6) | 30 (2.7) | 25 (2.5) | 43 (4.7) | 41 (3.7) | 307 (4.9) |

| E-cigarette use status | |||||||

| Current user | 71 (8.4) | 64 (5.3) | 38 (3.4) | 34 (3.4) | 36 (3.9) | 27 (2.4) | 270 (4.3) |

| Tried but not currently using | 177 (21.1) | 270 (22.4) | 142 (12.6) | 228 (22.6) | 281 (30.5) | 264 (23.9) | 1362 (21.9) |

| Never-user | 593 (70.5) | 874 (72.4) | 944 (84.0) | 747 (74.0) | 604 (65.6) | 815 (73.7) | 4577 (73.7) |

Current e-cigarette user: daily, weekly or monthly use.

CPD, cigarettes per day; FM, factory made cigarettes; RYO, roll-your-own cigarettes; SD, standard deviation.

Next, generalized estimating equation (GEE) (adjusted) multinomial regression models were used to test whether the perceived harmfulness of e-cigarettes changed from 2016 to 2018. An initial GEE model tested the main effect of the survey year (wave) on perceptions of harmfulness. A second GEE model tested for an interaction between country and wave to examine whether perceptions changed significantly from 2016 to 2018 in each of the six countries. Both the main effect and interaction models controlled for sex, age, degree of urbanization, income, education, smoking status, CPD, e-cigarette use status (current e-cigarette user vs. non-user) and time-in-sample (TIS: the number of times a respondent participated in the study). The model that tested the interaction also included the main effects of both country and wave. False discovery rate (FDR) adjustments were used to account for multiple comparisons.

Finally, two separate GEE logistic regression models tested whether there were differences in relative perceptions of harmfulness by (i) country (Hungary was used as the reference group as respondents there had the highest perception that e-cigarettes are less harmful, in line with scientific consensus); and (ii) e-cigarette use status (‘current e-cigarette user’ vs. ‘tried but not currently using an e-cigarette’ vs. ‘never tried/used an e-cigarette’). Weighted estimates for 2016 and 2018 were pooled and averaged for each response, and then were dichotomized by ‘less harmful’ vs. ‘other’ (equally/more harmful/don’t know) (Model 1), and then ‘equally/more harmful’ vs. ‘other’ (less harmful/don’t know) (Model 2). Both models adjusted for sex, age, education, income, degree of urbanization, smoking status, CPD, survey wave (2016 vs. 2018) and TIS.

All analyses were conducted using SAS-callable SUDAAN Version 11.0.1 to account for the sampling design. All GEE analyses were conducted using weighted data.

Ethics approval

The survey protocols and all materials, including the survey questionnaires, were cleared for ethics by the ethics research committee at the University of Waterloo (Ontario, Canada), and ethics committees in Germany (Ethikkommission der Medizinischen Fakultät Heidelberg), in Greece (Medical School, University of Athens—Research and Ethics Committee), in Hungary (Medical Research Council—Scientific and Research Committee), in Poland (State College of Higher Vocational Education—Committee and Dean of the Department of Health Care and Life Sciences), in Romania (Iuliu Hatieganu University of Medicine and Pharmacy) and in Spain (Clinical Research Ethics Committee of Bellvitge, Hospital Universitari de Bellvitge, Catalonia).

Results

Eligible respondents

In 2016, 6011 smokers completed the survey. Of those, 4266 had both heard of e-cigarettes and responded to the outcome variable (relative harm perceptions). In 2018, 6027 respondents completed the survey (re-contact: n = 3195; replenishment: n = 2832), of whom 4327 completed the relative harm perception question. Of the 3195 respondents re-contacted at Wave 2 (53.2% of Wave 1 respondents), 415 reported having quit smoking and 298 answered the relative harm perception question. Overall, there were a total of 6675 individual responses to the relative harm perception question across the 2016 and 2018 survey waves. A study flow diagram is presented in Supplementary figure S1.

Table 1 presents unweighted baseline respondent characteristics for those included in the current study. Overall, the average age of the sample was 44.1 ± 14.1 years, 47.5% were female, 96.3% were daily smokers and 4.3% of the sample were current e-cigarette users (ranging from 2% in Spain to 8% in Germany).

Perceptions of harmfulness of e-cigarettes compared to combustible cigarettes

Supplementary table S2 and Figure 1a–c present the estimates (overall and by country) for perceptions of harmfulness of e-cigarettes compared to cigarettes in 2016–2018. The main effect model (which tested the main effect of survey wave), was significant (χ2 = 8.24, P = 0.041); however, after the FDR adjustment for multiple comparisons, there were no significant changes in any perceptions between 2016 and 2018. In addition, the interaction of country and wave was not significant (χ2 = 24.68, P = 0.054).

Figure 1.

(a) Perception that e-cigarettes are less harmful than cigarettes. (b) Perception that e-cigarettes are equally or more harmful than cigarettes. (c) Don’t know if e-cigarettes are more, equally or less harmful than cigarettes

Perceptions of harm of e-cigarettes compared to combustible cigarettes by country

Less harmful

There was no overall change across the six countries for relative perceptions of e-cigarettes as being less harmful compared to combustible cigarettes. Hungary (34.1%) and Greece (33.5%) had the highest proportion of respondents who reported that e-cigarettes are less harmful in 2016, and Hungary in 2018 (35.1%). Romania (in 2016 and 2018) and Spain (in 2016) had the lowest proportions of respondents who believed this (figure 1a).

Equally or more harmful

The perception that e-cigarettes are ‘equally harmful’ was fairly stable across all countries over time; however, the perception that e-cigarettes are ‘more harmful’ increased in five of the six countries (excluding Spain), but the differences were not statistically significant (Supplementary table S2).

Perceiving e-cigarettes to be either ‘equally’ or ‘more harmful’ increased in Greece (58.5% to 62.1%), Hungary (52.9% to 57.0%) and Spain (58.7% to 64.4%). Germany (62.7%) had the highest proportion of respondents who reported this in 2016, and Spain in 2018 (64.4%) (figure 1b).

Don’t know

‘Don’t know’ responses decreased over time in four of the six countries; however, only in Spain did this reach statistical significance (19.3–9.4%, P ≤ 0.01). The largest proportion of respondents who reported uncertainty were from Spain in 2016 (19.3%), and Romania in 2018 (22.5%) (figure 1c).

Perceptions of harmfulness of e-cigarettes compared to combustible cigarettes (combined across both waves) by country and e-cigarette use status

Within the pooled analysis, compared to respondents from Hungary, respondents from Spain [odds ratio (OR) 0.56, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.40–0.77] and Romania (OR 0.45, 95% CI 0.33–0.62) were significantly less likely to believe that e-cigarettes are less harmful than combustible cigarettes. Respondents from Germany were significantly more likely to believe that e-cigarettes are equally or more harmful than respondents from Hungary (OR 1.43, 95% CI 1.04–1.96). There was no interaction effect between country and survey wave (F = 1.61, P = 0.16) (Supplementary table S3).

E-cigarette use status was related to perceptions of harmfulness, such that current e-cigarette users (OR 4.03, 95% CI 3.05–5.33), and those who reported having tried but not currently using e-cigarettes (OR 1.47, 95% CI 1.26–1.73), were significantly more likely to believe that e-cigarettes are less harmful than those who had never tried an e-cigarette. In addition, current e-cigarette users were significantly less likely to believe that e-cigarettes were equally or more harmful than cigarettes (OR 0.40, 95% CI 0.31–0.52) compared to those who had never tried an e-cigarette (Supplementary table S3). There was no significant interaction between e-cigarette use and survey wave for either model: Model 1: less harmful (F = 0.001, P = 0.99) and Model 2: equally/more harmful (F = 0.91, P = 0.40).

Discussion

The current study examined perceptions of harmfulness of e-cigarettes compared to combustible cigarettes and found that the majority of respondents in these six EU countries perceived e-cigarettes to be equally or more harmful than combustible cigarettes, both prior to the implementation of the TPD (2016), as well as at the post-TPD (2018) time period. These findings do not align with the existing scientific evidence indicating that e-cigarettes are less harmful than cigarettes and other combustible tobacco products,8,10 but they are consistent with the growing perceptions in other countries that e-cigarettes are at least equally as harmful as cigarettes.12,13 It is notable, however, that smokers from these six EU countries generally have much more negative perceptions of e-cigarettes than smokers from other high income, westernized countries.25,26

There is a paucity of published literature examining whether perceptions of the relative harmfulness of e-cigarettes compared to combustible cigarettes differ under different regulatory frameworks. One study by Yong et al.23 examined whether current and former smokers’ relative perceptions of e-cigarette harm varied under different e-cigarette regulatory environments. The results showed that the perception that e-cigarettes are less harmful than conventional cigarettes was considerably higher in the UK where the use of e-cigarettes to replace combustible cigarettes is encouraged for harm reduction purposes than in Australia, which has much stricter regulatory policies as e-cigarettes with nicotine are prohibited.27 The authors suggested that these results may be attributable to the less restrictive e-cigarette policies in the UK, e.g. allowing e-cigarettes with nicotine to be sold on the open market.

After the implementation of the stricter TPD regulations, there were small but mostly non-significant changes in perceptions of the harmfulness of e-cigarettes compared to combustible cigarettes, including a slight increase in the perception that e-cigarettes are equally or more harmful than cigarettes. Overall, there was a small decrease over time in the proportion who reported being uncertain; this was evident in four of the six countries, but significant only in Spain. After the TPD, Romania had the highest rate of uncertainty about the harm of e-cigarettes relative to cigarettes, where nearly a quarter of the respondents were unsure. Notably, after the TPD, Romania also had the lowest proportion of respondents who reported that e-cigarettes were less harmful.

This study did not show significant differences between countries in changes over time regarding perceptions of harm. However, when responses were averaged across waves, Hungary and Greece had the highest proportion of respondents who perceived e-cigarettes to be less harmful than combustible cigarettes, a perception consistent with the current scientific evidence. Respondents from Romania and Spain were significantly less likely to believe that e-cigarettes are less harmful than conventional cigarettes than respondents from Hungary, which may be a reflection of differing social norms such as perceived public approval. For example, in a recent EUREST-PLUS ITC paper by East et al.,28 Romania and Spain had the lowest proportion of smokers who reported believing that the public approves of e-cigarettes, and Hungary had the highest proportion. This suggests that perceptions of public acceptance towards e-cigarettes may be associated with e-cigarette harm perceptions.

The high proportion of respondents who perceive e-cigarettes to be equally or more harmful than cigarettes in the EU, and the shifting towards this opinion in several other countries, may be associated with multiple factors, such as divided opinions among the scientific community, the lack of accurate, consistent and proactive risk communications to the public, information from media reports, or the growing interest of multinational tobacco firms in the e-cigarette market. Perhaps most importantly, reporting about the associations of e-cigarettes with health problems and safety concerns may not only impact peoples’ absolute harm perceptions of e-cigarettes but may negatively impact peoples’ relative harm perceptions compared to combustible cigarettes, thereby leading the public to become more cautious and sceptical about e-cigarettes as a harm reducing alternative to combustible cigarettes.

Perceptions of potential risks and benefits of e-cigarette use vary widely among the general public, as well as among those who smoke compared to those who use e-cigarettes. Research has consistently found that e-cigarette users are more likely to believe that e-cigarettes are less harmful than combustible cigarettes compared to never-e-cigarette users, smokers and non-smokers.12,13,25,29 Consistent with this, current e-cigarette users in this study were significantly more likely than those who had never used an e-cigarette and those who have tried e-cigarettes (but not currently using them) to believe e-cigarettes are less harmful (56.4% vs. 25.1%).

It has been reported that e-cigarettes are a popular smoking quit aid in the EU.20 A recent randomized trial in England indicated that second-generation e-cigarettes nearly doubled the percentage of smokers who were abstinent from cigarettes after one year (18%) compared to nicotine replacement therapy (NRT) (10%) when both products were accompanied by behavioural support,30 an updating of the initial evidence from two previous clinical trials showing the efficacy of first-generation e-cigarettes for quitting.31 Some observational studies have found that (daily) e-cigarette use can be helpful in attempts to stop smoking or reduce cigarette consumption,32 as well as smoking cessation,33–36 but other studies have not found an effect.37 However, it must be also remembered that a scientific consensus on the potential risks and benefits of e-cigarette use still has not been reached, and the public health debate continues. Similarly, it should be noted that there are other safe, well-researched and effective cessation products that can help smokers to quit, including, but not limited to NRT and Varenicline.38

Study limitations

This repeated cross-sectional study included a large sample of European smokers from six countries; however, there may be some limitations to consider. As respondents in this study were recruited as smokers, the results are not generalizable beyond the smoking population (e.g. to former or non-smokers). Second, the proportion of current e-cigarette users in the sample was small, therefore we could not examine whether smokers who perceived e-cigarettes to be less harmful were more likely to initiate e-cigarette use compared to those who held perceptions that e-cigarettes were equally or more harmful. Third, data were self-reported, and thus may have been subject to misclassification due to social desirability bias.

Conclusion

Overall, this study has demonstrated that on average, smokers in these six EU countries overestimated the relative harmfulness of e-cigarettes compared to combustible cigarettes. As the global use of e-cigarettes continues to increase, leveraging different modes of health communication to discourage e-cigarette use among never-smokers, especially youth, is critical. However, equally critical is the provision of balanced information to those smokers who are interested in using e-cigarettes in place of combustible cigarettes. Such communication should be framed to distinguish relative and absolute harms, providing an evidence-based appraisal of the relative risk of e-cigarettes in comparison to combustible cigarettes.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

Provenance and peer review: Commissioned; externally peer-reviewed. EUREST-plus consortium members: European Network on Smoking and Tobacco Prevention (ENSP), Belgium: Constantine I. Vardavas, Andrea Glahn, Christina N. Kyriakos, Dominick Nguyen, Katerina Nikitara, Cornel Radu-Loghin and Polina Starchenko. University of Crete (UOC), Greece: Aristidis Tsatsakis, Charis Girvalaki, Chryssi Igoumenaki, Sophia Papadakis, Aikaterini Papathanasaki, Manolis Tzatzarakis and Alexander I. Vardavas. Kantar Public, Belgium: Nicolas Bécuwe, Lavinia Deaconu, Sophie Goudet, Christopher Hanley and Oscar Rivière. Smoking or Health Hungarian Foundation (SHHF), Hungary: Tibor Demjén, Judit Kiss and Anna Piroska Kovacs. Tobacco Control Unit, Catalan Institute of Oncology (ICO) and Bellvitge Biomedical Research Institute (IDIBELL), Catalonia: Esteve Fernández, Yolanda Castellano, Marcela Fu, Sarah O. Nogueira and Olena Tigova. Kings College London (KCL), UK: Ann McNeill, Katherine East and Sara C. Hitchman. Cancer Prevention Unit and WHO Collaborating Centre for Tobacco Control, German Cancer Research Center (DKFZ), Germany: Ute Mons and Sarah Kahnert. National and Kapodistrian University of Athens (UoA), Greece: Yannis Tountas, Panagiotis Behrakis, Filippos T. Filippidis, Christina Gratziou, Paraskevi Katsaounou, Theodosia Peleki, Ioanna Petroulia and Chara Tzavara. Aer Pur Romania, Romania: Antigona Carmen Trofor, Marius Eremia, Lucia Lotrean and Florin Mihaltan. European Respiratory Society (ERS), Switzerland: Gernot Rohde, Tamaki Asano, Claudia Cichon, Amy Far, Céline Genton, Melanie Jessner, Linnea Hedman, Christer Janson, Ann Lindberg, Beth Maguire, Sofia Ravara, Valérie Vaccaro and Brian Ward. Maastricht University, the Netherlands: Marc Willemsen, Hein de Vries, Karin Hummel and Gera E. Nagelhout. Health Promotion Foundation (HPF), Poland: Witold A. Zatoński, Aleksandra Herbeć, Kinga Janik-Koncewicz, Krzysztof Przewoźniak and Mateusz Zatoński. University of Waterloo (UW), Canada: Geoffrey T. Fong, Thomas K. Agar, Pete Driezen, Shannon Gravely, Anne C. K. Quah and Mary E. Thompson.

Funding

The EUREST-PLUS project has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under grant agreement No 681109 (CIV) and the University of Waterloo (GTF). Additional support was provided to the University of Waterloo by a foundation grant from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (FDN-148477). G.T.F. was supported by a Senior Investigator Grant from the Ontario Institute for Cancer Research. E.F. is partly supported by Ministry of Universities and Research, Government of Catalonia (2017SGR319) and by the Instituto Carlos III and co-funded by the European Regional Development Fund (FEDER) (INT16/00211 and INT17/00103), Government of Spain. E.F. thanks CERCA Programme Generalitat de Catalunya for the institutional support to IDIBELL.

Conflicts of interest: G.T.F. has served as an expert witness on behalf of governments in litigation involving the tobacco industry. K.J-.K. reports grants and personal fees from the Polish League Against Cancer, outside the submitted work. All other authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Key points

The majority of smokers in the six EU countries included in this study (Germany, Greece, Hungary, Poland, Romania and Spain) perceived e-cigarettes to be equally or more harmful than combustible cigarettes in 2016 and 2018 (∼60%), and approximately 30% believed that e-cigarettes are less harmful than cigarettes.

It does not appear that the implementation of the European Tobacco Products Directive had a significant impact on relative harm perceptions over time.

Overall, across both waves (2016 and 2018), respondents from Hungary had the highest proportion of smokers who perceived e-cigarettes to be less harmful than combustible cigarettes (35.6%), followed by Greece (33.2%) and Germany (29.7%). Respondents from Spain and Romania were the most negative about relative harm (23.9% and 20.6% perceived e-cigarettes as less harmful respectively).

Respondents who self-reported current e-cigarette use were four times more likely than never-e-cigarette users to perceive e-cigarettes to be less harmful than cigarettes. Those who had ever-tried (but not current e-cigarette users) were 1.5 times more likely to believe e-cigarettes to be less harmful than never-users.

This study has demonstrated that smokers in the EU commonly overestimate the relative risk of e-cigarettes compared to combustible cigarettes. Therefore, public health communication should be framed to reduce the confusion between relative and absolute harms.

Contributor Information

the EUREST-PLUS Consortium:

Constantine I Vardavas, Andrea Glahn, Christina N Kyriakos, Dominick Nguyen, Katerina Nikitara, Cornel Radu-Loghin, Polina Starchenko, Aristidis Tsatsakis, Charis Girvalaki, Chryssi Igoumenaki, Sophia Papadakis, Aikaterini Papathanasaki, Manolis Tzatzarakis, Alexander I Vardavas, Nicolas Bécuwe, Lavinia Deaconu, Sophie Goudet, Christopher Hanley, Oscar Rivière, Tibor Demjén, Judit Kiss, Anna Piroska Kovacs, Esteve Fernández, Yolanda Castellano, Marcela Fu, Sarah O Nogueira, Olena Tigova, Ann McNeill, Katherine East, Sara C Hitchman, Ute Mons, Sarah Kahnert, Yannis Tountas, Panagiotis Behrakis, Filippos T Filippidis, Christina Gratziou, Paraskevi Katsaounou, Theodosia Peleki, Ioanna Petroulia, Chara Tzavara, Antigona Carmen Trofor, Marius Eremia, Lucia Lotrean, Florin Mihaltan, Gernot Rohde, Tamaki Asano, Claudia Cichon, Amy Far, Céline Genton, Melanie Jessner, Linnea Hedman, Christer Janson, Ann Lindberg, Beth Maguire, Sofia Ravara, Valérie Vaccaro, Brian Ward, Marc Willemsen, Hein de Vries, Karin Hummel, Gera E Nagelhout, Witold A Zatoński, Aleksandra Herbeć, Kinga Janik-Koncewicz, Krzysztof Przewoźniak, Mateusz Zatoński, Geoffrey T Fong, Thomas K Agar, Pete Driezen, Shannon Gravely, Anne C K Quah, and Mary E Thompson

References

- 1.World Health Organization. Tobacco: Deadly in Any Form or Disguise. World No Tobacco Day, 2006. Available at: https://www.who.int/tobacco/communications/events/wntd/2006/Report_v8_4May06.pdf (24 July 2019, date last accessed).

- 2.National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion (US) Office on Smoking and Health. The Health Consequences of Smoking—50 Years of Progress: A Report of the Surgeon General, 2014. Atlanta (GA): Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (US). Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK179276/pdf/Bookshelf_NBK179276.pdf (24 July 2019, date last accessed). [PubMed]

- 3. Doll R, Peto R, Boreham J, Sutherland I. Mortality in relation to smoking: 50 years’ observations on male British doctors. BMJ 2004;328:1519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Pirie K, Peto R, Reeves GK, et al. The 21st century hazards of smoking and benefits of stopping: a prospective study of one million women in the UK. Lancet 2013;381:133–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Russell MA. Low-tar medium-nicotine cigarettes: a new approach to safer smoking. Br Med J 1976;1:1430–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Thun MJ, Burns DM. Health impact of “reduced yield” cigarettes: a critical assessment of the epidemiological evidence. Tob Control 2001;10 Suppl 1:i4–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Tindle HA, Rigotti NA, Davis RB, et al. Cessation among smokers of “light” cigarettes: results from the 2000 national health interview survey. Am J Public Health 2006;96:1498–504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Public Health Consequences of E-Cigarettes. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press, 2018. Available at: http://nationalacademies.org/hmd/Reports/2018/public-health-consequences-of-e-cigarettes.aspx (24 July 2019, date last accessed). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. McNeill A, Brose LS, Calder R, McRobbie H Vaping in England: An Evidence Update February 2019: A Report Commissioned by Public Health England. London, UK: Public Health England, 2019. Available at: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/781748/Vaping_in_England_an_evidence_update_February_2019.pdf (24 July 2019, date last accessed).

- 10.Royal College of Physicians. Nicotine Without Smoke: Tobacco Harm Reduction. London: RCP, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 11.American Cancer Society. American Cancer Society Position Statement on Electronic Cigarettes 2018. Available at: https://www.cancer.org/healthy/stay-away-from-tobacco/e-cigarette-position-statement.html (24 July 2019, date last accessed).

- 12. Romijnders K, van Osch L, de Vries H, Talhout R. Perceptions and reasons regarding e-cigarette use among users and non-users: a narrative literature review. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2018;15:1190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Huang J, Feng B, Weaver SR, et al. Changing perceptions of harm of e-cigarette vs cigarette use among adults in 2 US National Surveys From 2012 to 2017. JAMA Netw Open 2019;2:e191047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Nicksic NE, Snell LM, Barnes AJ. Reasons to use e-cigarettes among adults and youth in the Population Assessment of Tobacco and Health (PATH) study. Addict Behav 2019;93:93–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Yong HH, Borland R, Cummings KM, et al. Reasons for regular vaping and for its discontinuation among smokers and recent ex-smokers: findings from the 2016 ITC Four Country Smoking and Vaping Survey. Addiction 2019;114:35–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Twyman L, Watts C, Chapman K, Walsberger SC. Electronic cigarette use in New South Wales, Australia: reasons for use, place of purchase and use in enclosed and outdoor places. Aust N Z J Public Health 2018;42:491–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Huerta TR, Walker DM, Mullen D, et al. Trends in e-cigarette awareness and perceived harmfulness in the U.S. Am J Prev Med 2017;52:339–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Farsalinos KE, Romagna G, Tsiapras D, et al. Characteristics, perceived side effects and benefits of electronic cigarette use: a worldwide survey of more than 19,000 consumers. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2014;11:4356–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Brose LS, Brown J, Hitchman SC, McNeill A. Perceived relative harm of electronic cigarettes over time and impact on subsequent use. A survey with 1-year and 2-year follow-ups. Drug Alcohol Depend 2015;157:106–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Filippidis FT, Laverty AA, Mons U, et al. Changes in smoking cessation assistance in the European Union between 2012 and 2017: pharmacotherapy versus counselling versus e-cigarettes. Tob Control 2019;28:95–100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Persoskie A, O'Brien EK, Poonai K. Perceived relative harm of using e-cigarettes predicts future product switching among U.S. adult cigarette and e-cigarette dual users. Addiction 2019;114:2197–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Institute for Global Tobacco Control. John Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health.Country Laws Regulating E-Cigarettes: A Policy Scan. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, 2018. Available at: https://www.globaltobaccocontrol.org/e-cigarette_policyscan (24 July 2019, date last accessed). [Google Scholar]

- 23. Yong H-H, Borland R, Balmford J, et al. Prevalence and correlates of the belief that electronic cigarettes are a lot less harmful than conventional cigarettes under the different regulatory environments of Australia and the United Kingdom. Nicotine Tob Res 2017;19:258–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Thompson ME, Driezen P, Boudreau C, et al. Methods of the International Tobacco Control (ITC) EUREST-PLUS ITC Europe Surveys. Eur J Public Health 2020;30:iii4–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Fong GT, Elton-Marshall T, Driezen P, et al. U.S. adult perceptions of the harmfulness of tobacco products: descriptive findings from the 2013-14 baseline wave 1 of the path study. Addict Behav 2019;91:180–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Elton-Marshall T, Fong GT, Li G, et al. Perceptions of the harmfulness of e-cigarettes across 20 countries: findings from the ITC Project. Evidence on e-cigarettes use and perceptions, and the implications for tobacco control: Canadian and international perspectives. In: Proceedings of the Canadian Public Health Association Symposium, 28–31 May 2018, Montreal (QC).

- 27. Kennedy RD, Awopegba A, De León E, Cohen JE. Global approaches to regulating electronic cigarettes. Tob Control 2017;26:440–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. East KA, Hitchman SC, McDermott M, McNeill A, et al. ; EUREST-PLUS consortium. Social norms towards smoking and electronic cigarettes among adult smokers in seven European Countries: findings from the EUREST-PLUS ITC Europe Surveys. Tob Induc Dis 2018;16:A15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Cooper M, Loukas A, Harrell MB, Perry CL. College students’ perceptions of risk and addictiveness of e-cigarettes and cigarettes. J Am Coll Health 2017;65:103–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Hajek P, Phillips-Waller A, Przulj D, et al. A randomized trial of e-cigarettes versus nicotine-replacement therapy. N Engl J Med 2019;380:629–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. McRobbie H, Bullen C, Hartmann-Boyce J, Hajek P. Electronic cigarettes for smoking cessation and reduction. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2014;12:CD010216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Brose LS, Hitchman SC, Brown J, et al. Is the use of electronic cigarettes while smoking associated with smoking cessation attempts, cessation and reduced cigarette consumption? A survey with a 1-year follow-up. Addiction 2015;110:1160–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Jackson S, Kotz D, West R, Brown J. Moderators of real-world effectiveness of smoking cessation aids: a population study. Addiction 2019;114:1627–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Coleman B, Rostron B, Johnson SE, et al. Transitions in electronic cigarette use among adults in the Population Assessment of Tobacco and Health (PATH) Study, Waves 1 and 2 (2013-2015). Tob Control 2019;28:50–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Farsalinos K, Niaura R. E-cigarettes and smoking cessation in the United States according to frequency of e-cigarette use and quitting duration: analysis of the 2016 and 2017 National Health Interview Surveys. Nicotine Tob Res 2019; pii: ntz025. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntz025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Liu X, Lu W, Liao S, et al. Efficiency and adverse events of electronic cigarettes: a systematic review and meta-analysis (PRISMA-compliant article). Medicine (Baltimore) 2018;97:e0324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Weaver SR, Huang J, Pechacek TF, et al. Are electronic nicotine delivery systems helping cigarette smokers quit? Evidence from a prospective cohort study of U.S. adult smokers, 2015-2016. PLoS One 2018;13:e0198047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Fiore M. United States Tobacco Use and Dependence Guideline Panel. Treating Tobacco Use and Dependence: 2008 Update. Rockville, MD: Dept. of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, 2008. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.