Abstract

Introduction:

Although next-generation sequencing (NGS) has brought insight into critical mutations or pathways (e.g. DNA damage sensing and repair) involved in the etiology of many cancers and directed new screening, prevention, and therapeutic approaches for patients and families, NGS has only recently been utilized in malignant pleural mesotheliomas (MPMs).

Methods:

We analyzed blood samples from patients with MPM using the NGS platform MSK-IMPACT™ to explore cancer-predisposing genes. Loss of function variants or pathogenic entries were identified and clinicopathologic information was collected.

Results:

Of 84 patients with MPM, 12% (10/84) had pathogenic variants. Clinical characteristics were similar between cohorts, although patients with germline pathogenic variants were more likely to have more than 2 first-degree family members with cancer than those without germline mutations (40% vs 12%; Fisher’s exact test, p < 0.05). Novel deleterious variants in mesotheliomas included MSH3 (1% [1/84]; 95% CI: 0–7%), BARD1 (1% [1/84]; 95% CI: 0–7%), and RECQL4 (2% [2/84]; 95% CI: 0–9%). Pathogenic variants previously reported on germline testing in patients with mesotheliomas were BAP1 (4% [3/84]; 95% CI: 1–10%), BRCA2 (1% [1/84]; 95% CI: 0–7%), and MRE11A (1% [1/84]; 95% CI: 0–7%). One patient (1% [1/84]; 95% CI: 0–7%) had a likely pathogenic alteration in SHQ1 that has not been associated with a heritable susceptibility to cancer.

Conclusions:

Our study lends further support for the role of aberrations in DNA damage repair genes in the pathogenesis of malignant pleural mesotheliomas and suggests that targeting members of these pathways for screening and treatment warrants further studying.

Keywords: Mesothelioma, Genetic testing, Germline mutation, Biomarker, DNA damage

Introduction

Efforts to characterize the germline genetic landscape of malignant pleural mesotheliomas (MPM) have uncovered pathogenic variants involved in DNA damage repair and chromatin remodeling.1 Germline mutations in BAP1, which encodes a deubiquitinase that regulates nuclear proteins, were the first to be associated with MPM.2 Through multiple mechanisms resulting from decreased or abrogated BAP1 activity, including altered cytoplasmic Ca2+ regulation required for apoptosis, inhibited ferroptosis, and impaired DNA damage repair, BAP1-mutated cells are prone to accumulate DNA damage and, thus, malignant transformation.3, 4 Recent studies have identified other candidate genes associated with MPM.5, 6 Importantly, observations from these studies could direct new screening, prevention, and therapeutic approaches for patients and families. For instance, BAP1 mutations may predict response to immunotherapy in patients with mesotheliomas.7 In addition, BAP1 mutations and germline mutations in DNA damage repair confer a survival benefit to patients with MPM receiving treatment with platinum-based chemotherapy.5 Understanding genetic factors that underlie or contribute to the development of mesothelioma is leading to the identification of potential biomarkers and targets for systemic therapy.

Utilizing a DNA-based next-generation sequencing (NGS) platform developed at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (MSK), we set out to identify germline alterations in patients with mesotheliomas.8 Here, we describe previously unreported germline mutations involved in DNA damage repair found in patients with mesotheliomas.

Methods

Patient recruitment and enrollment

This study was conducted with approval from the MSK institutional review board. All study participants provided written informed consent before their inclusion. Patients with pleural mesotheliomas of all stages were identified from a mesothelioma cohort that was prospectively enrolled on a germline BAP1 ascertainment study.9 We collected clinicopathologic data including age of diagnosis, sex, environmental exposure, and family history.

Mutational analyses

Blood samples were obtained from patients with MPM who had received clinical care at MSK from March 2013 to October 2016. Deidentified analysis was performed using a New York State Department-approved, targeted DNA NGS platform (MSK-IMPACT™).8 The NGS platform evolved during the study, increasing from 341 to 468 genes. A list of interrogated genes is included in Supplemental Table 1. The average depth of coverage was >150x and germline variants were called if allele fractions were >25% for single-nucleotide variants or >15% for insertions/deletions. Genetic alterations were screened for loss of function variants or pathogenic entries in ClinVar (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/clinvar/), a freely available archive that documents genetic variants of clinical significance. Variants were reviewed according to the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and Association for Molecular Pathology consensus guidelines. Loss of heterozygosity was evaluated using the FACETS (Fraction and Allele-Specific Copy Number Estimates from Tumor Sequencing) analysis pipeline.10 Patients who consented to germline testing and were identified were referred to a familial cancer clinic. De-identified cases were not referred.

Statistical Analyses

Statistical comparisons were performed using Fisher’s exact test. Reported p-values are for 2-sided hypothesis tests with p < 0.05 considered significant.

Results

Eighty-eight patients with MPM and germline NGS sequencing were identified. Germline variants were found in 18 (20%; 95% CI: 13–30%) patient samples. After excluding four cases of variants of unknown significance (VUS) and four cases of founder mutations (2 in BRCA2 and 2 in APC), 84 total patient samples remained for analysis and 14 (78%) germline mutations were found (Table 1; Supplemental Table 2).11 Founder mutations were excluded from the analysis because the background rate of founder mutations in this cohort is unknown. The FACETS analysis pipeline and software indicated that all germline mutations identified were heterozygous.

Table 1. Characteristics of Patients with Germline Mutations.

Specific germline mutations, whether they involve DNA damage repair (DDR), family histories, personal cancer history, age of diagnoses of patients with mesothelioma in this cohort are listed.

| Age at Diagnosis | Germline Mutation | Involved in DDR | Histologic Subtype | Personal Cancer History | Cancers in First-Degree Relatives |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 49 | BAP1 c.580+1G>A | Yes | Epithelioid | Basal Cell Carcinoma | Ocular Melanoma |

| 57 | BAP1 c.1777C>T | Yes | Epithelioid | Melanoma | Hepatocellular Carcinoma, Mesothelioma |

| 74 | BAP1 c.437+1G>T | Yes | Epithelioid | Hepatocellular Carcinoma | Hepatocellular Carcinoma |

| 85 | BARD1 c.1216C>T | Yes | Epithelioid | Basal Cell Carcinoma | Breast Cancer, Cholangiocarcinoma, Basal Cell Carcinoma, Melanoma |

| 47 | BRCA2 c.4631delA | Yes | Epithelioid | None | Oral Cancer |

| 76 | MRE11A c.504_511delGCTT CAAA | Yes | Epithelioid | Lung | Lymphoma, Renal Cell Carcinoma, Lung, Prostate, and Esophageal cancers |

| 82 | MSH3 c.1653+1G>A | Yes | Sarcomatoid | None | Colon, Lung, and Breast Cancers |

| 71 | RECQL4 c.24641G>C | Yes | Epithelioid | None | Breast and Colon Cancers, Hepatocellular Carcinoma |

| 33 | RECQL4 exon 13–15 deletion | Yes | Sarcomatoid | None | Lymphoma, Prostate Cancer |

| 72 | SHQ1 c.828_831delTGAT | No | Epithelioid | None | None |

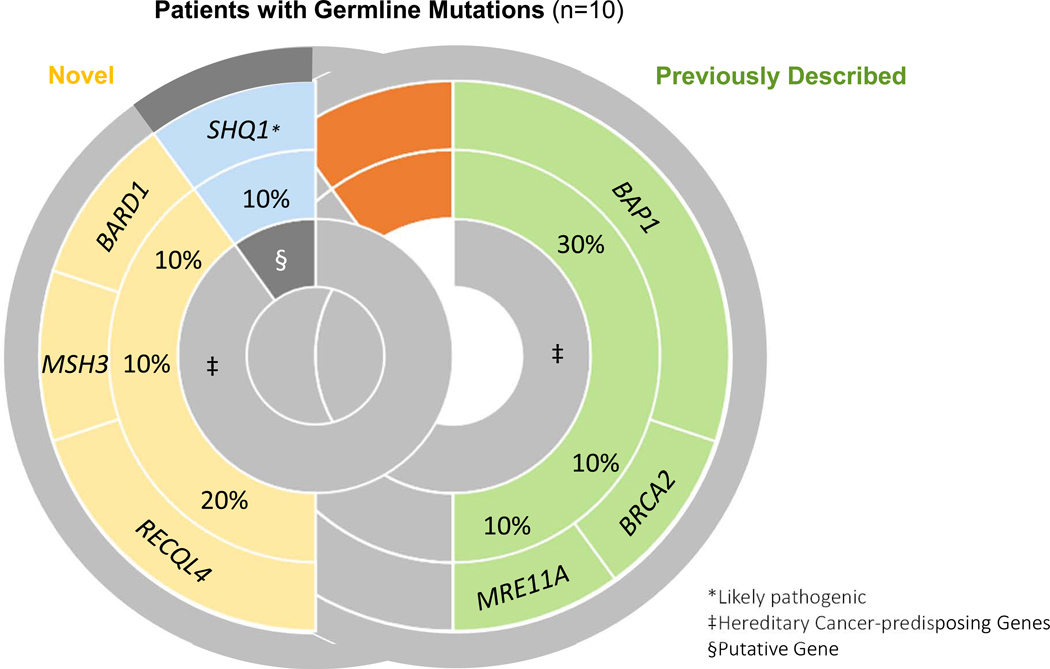

The clinical characteristics of patients with or without germline mutations were similar (Table 2). For all patients, the median age at diagnosis was 69 years (interquartile range 60 to 74 years) and patients were mostly male (68%, 57/84), non-Hispanic white (87%, 73/84), former or current smokers (57%, 48/84), and reported definite or probable classic occupational exposure to asbestos (61%, 51/84). Most patients also had at least 1 first-degree relative with cancer (68%, 57/84). Epithelioid histology was the predominant tumor type (80%, 67/84). Patients with germline mutations were more likely than those without to have more than 2 first-degree relatives with cancer (40% vs 12%, respectively; p < 0.05). The prevalence of previously reported mutations in BAP1, BRCA2, and MRE11A in our cohort were: BAP1 (3/84 [4%; 95% CI: 1–10%]), BRCA2 (1/84 [1%; 95% CI: 0–7%]), and MRE11A (1/84 [1%; 95% CI: 0–7%]). Mutations in MSH3 (1/84 [1%; 95% CI: 0–7%]), BARD1 (1/84 [1%; 95% CI: 0–7%]), and RECQL4 (2/84; [2%; 95% CI: 0–9%]), and SHQ1 (1/84 [1%; 95% CI: 0–7%]) have not been previously reported in mesotheliomas but were identified in our cohort (Figure 1). Of note, MSH3 was the only identified gene that was not interrogated on all versions of the NGS panel (Supplemental Table 1).

Table 2. Patient Demographics and Clinical Characteristics.

Clinicopathologic characteristics of patients with mesothelioma included in our study are provided. Of note, patients with variants of unknown significance or founder mutations on germline testing were excluded.

| Patients with Germline Mutations, 10 (%) | Patients without Germline Mutations, 74 (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Sex§ | ||

| Female | 4 (40) | 23 (31) |

| Male | 6 (60) | 51 (69) |

| Self-Declared Ethnicity§ | ||

| Non-Hispanic White | 9 (90) | 64 (86) |

| Asian | 1 (10) | 3 (4) |

| Hispanic | 0 | 5 (7) |

| Black | 0 | 2 (3) |

| Age at Diagnosis | ||

| Median (interquartile range) | 72 (49 – 78) | 69 (62 – 74) |

| Histology§ | ||

| Epithelioid | 8 (80) | 59 (80) |

| Sarcomatoid | 2 (20) | 0 |

| Mixed | 0 | 10 (14) |

| Not specified | 0 | 5 (7) |

| Clinical Stage at Diagnosis§ | ||

| Stage I | 4 (40) | 26 (35) |

| Stage II | 0 | 2 (3) |

| Stage III | 3 (30) | 35 (47) |

| Stage IV | 3 (30) | 11 (15) |

| Self-Reported Asbestos Exposure§ | ||

| Definite/Probable | 5 (50) | 46 (62) |

| None | 0 | 11 (15) |

| Unknown | 5 (50) | 17 (23) |

| Smoking History§ | ||

| Current | 0 (0) | 1 (1) |

| Former | 4 (40) | 43 (58) |

| Never | 6 (60) | 30 (41) |

| Personal History of Cancer* | ||

| Patients with Cancer | 5 (50) | 27 (35) |

| Basal Cell Carcinoma | 2 (20) | 4 (5) |

| Breast | 0 | 5 (7) |

| Colon | 0 | 1 (1) |

| Hepatocellular Carcinoma | 1 (10) | 0 |

| Lymphoma | 0 | 3 (4) |

| Lung Cancer | 1 (10) | 1 (1) |

| Melanoma | 1 (10) | 3 (4) |

| Ocular Melanoma | 0 | 1 (1) |

| Renal | 0 | 1 (1) |

| Prostate | 0 | 5 (7) |

| Squamous Cell Carcinoma | 0 | 2 (3) |

| Other | 0 | 3 (4) |

| Relatives with Cancer | ||

| First-degree relative (FDR) | 9 (90) | 48 (65) |

| >2 first-degree relatives | 4 (40) | 9 (12) |

| Second-degree relative | 3 (30) | 32 (43) |

| None | 1 (10) | 16 (22) |

Percentages were rounded, so may not total 100%.

Some patients had more than one cancer

Figure 1. Distribution of Pathogenic Variants in Patients with Positive Germline Findings.

The 10 germline pathogenic variants found in patients with mesothelioma were categorized by whether they have previously been reported in mesothelioma (previously described) or not (novel). Previous associations with hereditary cancer-predispoing syndromes are also noted.

Epithelioid histology was observed in the bulk of patients with deleterious mutations (80% [8/10]; 95% CI: 48–95%). Interestingly, half of the patients with a germline mutation did not have a personal history of another cancer. Breast was the most common cancer seen in first-degree relatives of patients with germline mutations (Table 1), and 1 patient with a germline BAP1 mutation also had a first-degree relative with mesothelioma.

Discussion

In our cohort of patients with mesotheliomas, the clinicopathologic characteristics of patients with germline mutations were similar to those without an identifiable germline alteration. Median age, race, and self-reported classic occupational asbestos exposure and smoking history were comparable between the groups. However, patients with germline mutations were more likely to have a familial history of cancer than patients without germline mutations.

The presence of germline mutations in the DNA damage repair genes BAP1, BRCA2, and MRE11A in our patient cohort supports previous studies identifying these genetic alterations as predisposing to mesotheliomas.5, 6 We also identified several novel germline mutations in DNA damage repair genes in patients with mesotheliomas. RECQL4 encodes for a DNA helicase and is involved in DNA repair, especially during periods of oxidative stress.12 Patients with homozygous germline mutations in this gene have an increased risk of developing osteosarcoma.13 MSH3 is involved in DNA mismatch-repair and has been linked to a subtype of colorectal adenomatous polyposis and colon cancer.14 In mouse models, knocking out MSH3 leads to tumor formation over time.15 BARD1 is involved in repairing double-strand breaks and is associated with familial breast cancer.16 In vitro and in vivo models have demonstrated that BARD1 mutations can lead to chromosomal instability and the development of cancer. Of note, both the RECQL4 and MSH3 germline mutations reported in this study are heterozygous, but these mutations have only been reported in cancer predisposition syndromes in biallelic states.13, 14 The contribution of germline heterozygous mutations in RECQL4 and MSH3 to the development of mesotheliomas requires further investigation.

Finally, 1 patient with a likely pathogenic SHQ1 mutation was also identified. Mutations in SHQ1 have neither been associated with a cancer-predisposition syndrome nor reported in patients with mesotheliomas. SHQ1 is a tumor suppressor gene involved in processing ribosomal and telomerase RNA and may play a role in prostate cancer recurrence.17

Excluding founder mutations, we identified germline mutations in 12% (10/84) of patients with mesotheliomas. Intriguingly, 90% (9/10) of these pathogenic germline variants (such as RECQL4, MSH3, and BARD1) involve DNA damage repair. However, further investigation is needed to evaluate whether these germline mutations increase the risk of mesotheliomas and whether disruption of DNA damage repair pathways other than BAP1 are critical to mesothelioma tumorigenesis. Furthermore, the small sample size is a limitation of this study and makes it difficult to determine whether the mutations found in this study are truly representative of the frequency of these mutations at the population level. In addition, because NGS can be less reliable than other sequencing methods (such as whole genome sequencing) with picking up large insertions/deletions and copy number changes, our results may be underrepresenting the frequency of germline mutations in this study.1

Nevertheless, our findings are consistent with previous work that around 12% of patients with MPM have germline mutations.5, 6 In addition, these other studies have shown the prevalence of germline mutations involving the DNA damage repair and tumor suppressor pathways in these patients.5, 6, 18 Several genes (such as MRE11A, BRCA2, and BAP1) have been identified in multiple studies and are therefore strongly implicated in the pathogenesis of MPM. We also identified other mutations in the DNA damage repair pathway that have not been previously described in MPM (such as MSH3, BARD1, and RECQL4), suggesting that other members of this pathway may be involved in MPM development. In addition, we uncovered a germline mutation in a tumor suppressor gene (SHQ1) that has not been previously described in MPM or other cancer-predisposing syndromes. This study supports the growing body of work suggesting that germline mutations in tumor suppressor and DNA damage repair pathway genes may play a role in mesothelioma tumorigenesis.5, 6, 18 Future screening and treatment strategies should involve targeting members of these pathways for study.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding: This work was partially supported by a Department of Defense Career Development Award to Dr. Zauderer [CA140385]; and a National Cancer Institute Cancer Center Support Grant to Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center [P30 CA008748]. The funders had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; or preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript.

Disclosures:

Dr. Kris reports grants from National Institutes of Health/National Cancer Institute, during the conduct of the study; personal fees and non-financial support from AstraZeneca, personal fees from Pfizer, personal fees and non-financial support from Regeneron, personal fees from WebMD, personal fees from OncLive, personal fees from Physicians Education Resources, personal fees from Research to Practice, grants and non-financial support from Genentech Roche, grants from PUMA Biotechnology, personal fees from Prime Oncology, personal fees from Intellisphere, personal fees from Creative Educational Concepts, personal fees from Peerview, personal fees from i3 Health, personal fees from Paradigm Medical Communications, personal fees from AXIS, personal fees from Carvive Systems, grants from The Lung Cancer Research Foundation, grants from National Institutes of Health/National Cancer Institute, outside the submitted work. Memorial Sloan Kettering has an institutional agreement with IBM for Watson for Oncology and receives royalties from IBM. Dr. Kris is an employee of Memorial Sloan Kettering.

Dr. Ladanyi reports grants from National Institutes of Health/National Cancer Institute, during the conduct of the study; grants from LOXO Pharmaceuticals, personal fees from Astra-Zeneca, personal fees from Bristol-Myers Squibb, personal fees from Takeda, personal fees from Bayer, personal fees from Merck, grants from Helsinn Therapeutics, outside the submitted work.

Dr. Robson has received honoraria from AstraZeneca, has served in a consulting or advisory role for AstraZeneca, Daiichi-Sankyo (uncompensated), McKesson, Merck (uncompensated), and Pfizer (uncompensated), has received research funding from AbbVie (institution), AstraZeneca (Institution), Invitae (Institution, in-kind), Medivation (Institution), Myriad (Institution, in-kind), Pfizer (institution), and Tesaro (institution), has received travel, accommodation and/or expenses from AstraZeneca, and editorial services from Pfizer.

In the last 3 years, Dr. Zauderer has received consulting fees from Epizyme, Sellas Life Sciences, Aldeyra Therapeutics, Novocure, and Atara and honoraria from Medical Learning Institute and OncLive. Memorial Sloan Kettering receives research funding from the Department of Defense, the National Institutes of Health, MedImmune, Epizyme, Polaris, Sellas Life Sciences, Bristol Myers Squibb, Millenium, Curis, and Roche for research conducted by Dr. Zauderer. Dr. Zauderer serves as Chair of the Board of Directors of the Mesothelioma Applied Research Foundation. Dr. Zauderer reports grants from National Institutes of Health/National Cancer Institute. Memorial Sloan Kettering has an institutional agreement with IBM for Watson for Oncology and receives royalties from IBM. Dr. Zauderer is an employee of Memorial Sloan Kettering.

The following authors have nothing to disclose: Robin Guo, Gowtham Jayakumaran, Mariel Duboff, Diana Mandelker

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Carbone M, Adusumilli PS, Alexander HR Jr., et al. Mesothelioma: Scientific clues for prevention, diagnosis, and therapy. CA Cancer J Clin 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Testa JR, Cheung M, Pei J, et al. Germline BAP1 mutations predispose to malignant mesothelioma. Nat Genet 2011;43:1022–1025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bononi A, Giorgi C, Patergnani S, et al. BAP1 regulates IP3R3-mediated Ca(2+) flux to mitochondria suppressing cell transformation. Nature 2017;546:549–553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhang Y, Shi J, Liu X, et al. BAP1 links metabolic regulation of ferroptosis to tumour suppression. Nat Cell Biol 2018;20:1181–1192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hassan R, Morrow B, Thomas A, et al. Inherited predisposition to malignant mesothelioma and overall survival following platinum chemotherapy. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2019;116:9008–9013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Panou V, Gadiraju M, Wolin A, et al. Frequency of Germline Mutations in Cancer Susceptibility Genes in Malignant Mesothelioma. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology 2018;36:2863–2871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shrestha R, Nabavi N, Lin YY, et al. BAP1 haploinsufficiency predicts a distinct immunogenic class of malignant peritoneal mesothelioma. Genome medicine 2019;11:8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cheng DT, Mitchell TN, Zehir A, et al. Memorial Sloan Kettering-Integrated Mutation Profiling of Actionable Cancer Targets (MSK-IMPACT): A Hybridization Capture-Based Next-Generation Sequencing Clinical Assay for Solid Tumor Molecular Oncology. J Mol Diagn 2015;17:251–264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zauderer MG, Jayakumaran G, DuBoff M, et al. Brief Report: Prevalence and Preliminary Validation of Screening Criteria to Identify Carriers of Germline BAP1 Mutations. J Thorac Oncol 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shen R, Seshan VE. FACETS: allele-specific copy number and clonal heterogeneity analysis tool for high-throughput DNA sequencing. Nucleic acids research 2016;44:e131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Foulkes WD, Knoppers BM, Turnbull C. Population genetic testing for cancer susceptibility: founder mutations to genomes. Nat Rev Clin Oncol 2016;13:41–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Werner SR, Prahalad AK, Yang J, et al. RECQL4-deficient cells are hypersensitive to oxidative stress/damage: Insights for osteosarcoma prevalence and heterogeneity in Rothmund-Thomson syndrome. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2006;345:403–409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang LL, Gannavarapu A, Kozinetz CA, et al. Association between osteosarcoma and deleterious mutations in the RECQL4 gene in Rothmund-Thomson syndrome. Journal of the National Cancer Institute 2003;95:669–674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Adam R, Spier I, Zhao B, et al. Exome Sequencing Identifies Biallelic MSH3 Germline Mutations as a Recessive Subtype of Colorectal Adenomatous Polyposis. Am J Hum Genet 2016;99:337–351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Edelmann W, Umar A, Yang K, et al. The DNA mismatch repair genes Msh3 and Msh6 cooperate in intestinal tumor suppression. Cancer Res 2000;60:803–807. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shakya R, Szabolcs M, McCarthy E, et al. The basal-like mammary carcinomas induced by Brca1 or Bard1 inactivation implicate the BRCA1/BARD1 heterodimer in tumor suppression. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2008;105:7040–7045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hieronymus H, Iaquinta PJ, Wongvipat J, et al. Deletion of 3p13–14 locus spanning FOXP1 to SHQ1 cooperates with PTEN loss in prostate oncogenesis. Nat Commun 2017;8:1081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pastorino S, Yoshikawa Y, Pass HI, et al. A Subset of Mesotheliomas With Improved Survival Occurring in Carriers of BAP1 and Other Germline Mutations. J Clin Oncol 2018:JCO2018790352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.