Abstract

Background

Body composition data from abdominal CT scans have the potential to opportunistically identify those at risk for future fracture.

Purpose

To apply automated bone, muscle, and fat tools to noncontrast CT to assess performance for predicting major osteoporotic fractures and to compare with the Fracture Risk Assessment Tool (FRAX) reference standard.

Materials and Methods

Fully automated bone attenuation (L1-level attenuation), muscle attenuation (L3-level attenuation), and fat (L1-level visceral-to-subcutaneous [V/S] ratio) measures were derived from noncontrast low-dose abdominal CT scans in a generally healthy asymptomatic adult outpatient cohort from 2004 to 2016. The FRAX score was calculated from data derived from an algorithmic electronic health record search. The cohort was assessed for subsequent future fragility fractures. Subset analysis was performed for patients evaluated with dual x-ray absorptiometry (n = 2106). Hazard ratios (HRs) and receiver operating characteristic curve analyses were performed.

Results

A total of 9223 adults were evaluated (mean age, 57 years ± 8 [standard deviation]; 5152 women) at CT and were followed over a median time of 8.8 years (interquartile range, 5.1–11.6 years), with documented subsequent major osteoporotic fractures in 7.4% (n = 686), including hip fractures in 2.4% (n = 219). Comparing the highest-risk quartile with the other three quartiles, HRs for bone attenuation, muscle attenuation, V/S fat ratio, and FRAX were 2.1, 1.9, 0.98, and 2.5 for any fragility fracture and 2.0, 2.5, 1.1, and 2.5 for femoral fractures, respectively (P < .001 for all except V/S ratio, which was P ≥ .51). Area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC) values for fragility fracture were 0.71, 0.65, 0.51, and 0.72 at 2 years and 0.63, 0.62, 0.52, and 0.65 at 10 years, respectively. For hip fractures, 2-year AUC for muscle attenuation alone was 0.75 compared with 0.73 for FRAX (P = .43). Multivariable 2-year AUC combining bone and muscle attenuation was 0.73 for any fragility fracture and 0.76 for hip fractures, respectively (P ≥ .73 compared with FRAX). For the subset with dual x-ray absorptiometry T-scores, 2-year AUC was 0.74 for bone attenuation and 0.65 for FRAX (P = .11).

Conclusion

Automated bone and muscle imaging biomarkers derived from CT scans provided comparable performance to Fracture Risk Assessment Tool score for presymptomatic prediction of future osteoporotic fractures. Muscle attenuation alone provided effective hip fracture prediction.

© RSNA, 2020

See also the editorial by Smith in this issue.

Summary

Automated bone and muscle imaging biomarkers derived from abdominal CT compared favorably with an established clinical assessment tool for fracture risk for presymptomatic prediction of osteoporotic fractures in a cohort of 9223 adults.

Key Results

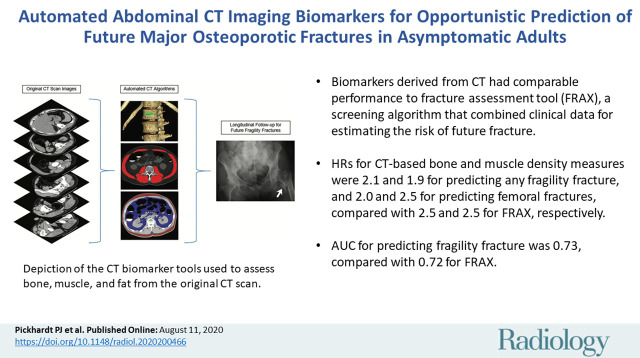

■ Biomarkers derived from abdominal CT had comparable performance to the Fracture Risk Assessment Tool (FRAX), a multivariable screening algorithm that combines clinical input data to estimate the risk of future fracture.

■ Hazard ratios for automatically derived CT-based bone and muscle attenuation measures were 2.1 and 1.9 for predicting any fragility fracture and 2.0 and 2.5 for predicting femoral fractures compared with 2.5 and 2.5 for FRAX, respectively.

■ The 2-year area under the receiver operating characteristic curve value for combined CT-based bone and muscle density for predicting fragility fracture was 0.73 compared with 0.72 for FRAX.

Introduction

Osteoporosis is a major public health concern that continues to grow in worldwide importance (1–3). Fragility fractures, defined as insufficiency fractures not related to high-impact trauma, are the major complication of this underdiagnosed and undertreated condition. Major osteoporotic fractures result in substantial morbidity and mortality, particularly for hip fractures (3,4). The Fracture Risk Assessment Tool (FRAX) is a well-established, validated multivariable screening algorithm that combines a variety of clinical input data for estimating the risk of future fracture (5). Although guidelines vary, the National Osteoporosis Foundation recommends treating patients with FRAX 10-year fracture risk scores greater than or equal to 20% for major osteoporotic fracture, or greater than or equal to 3% for hip fracture to reduce the risk (6). Dual x-ray absorptiometry (DXA) is the current imaging standard for bone mineral density screening and is included as an optional input variable in FRAX. However, DXA has inherent drawbacks, including its planar technique, low sensitivity for fracture prediction, and underutilization for population screening (7,8). FRAX itself is an opaque calculator that does not provide insight into its weighting of the many input variables and also requires manual data entry, which may further decrease population-based utilization. Importantly, other factors such as sarcopenia may play an important role in fracture risk but are not included in FRAX (9).

To help counter these issues, including the low screening rates, the opportunistic use of bone mineral density data derived from body CT scans performed for other indications may provide valuable screening information (10–12). Using manual techniques at CT with either vertebral trabecular attenuation values (10,11,13) or DXA-like femoral neck assessment (14,15) can serve as a potential substitute in the frequent absence of DXA screening. At the very least, opportunistic or incidental CT detection of patients at unsuspected increased risk for fracture could improve overall screening rates and potentially reduce the incidence of future fracture. For this scenario, CT-based prediction need not be better than FRAX, although comparable performance would be desirable.

Diagnostic imaging represents a logical application for artificial intelligence to medicine (16–19). In particular, cross-sectional CT scanning represents an ideal candidate modality for applying automated tools, providing rapid and objective volumetric data that is highly reproducible. Furthermore, abdominal (and chest) CT scans are commonly performed for a wide variety of indications (20). We have previously developed, trained, tested, and validated a fully automated algorithm for vertebral body bone mineral density screening on CT scans (21,22) as well as additional automated tools for assessing muscle, intra-abdominal fat, aortic calcification, and liver fat (23–26).

The purpose of our study was therefore to assess the ability of fully automated CT-based bone, muscle, and fat measures in the prediction of future major osteoporotic fractures in asymptomatic adults, comparing performance against the current FRAX reference standard.

Materials and Methods

Patient Cohort and CT Protocol

Our Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act–compliant investigation was approved by the institutional review board at the University of Wisconsin and the Office of Human Subjects Research Protection at the NIH Clinical Center. The requirement for written informed consent was waived for this retrospective assessment. This patient group represents an external test cohort for applying our validated tools that were previously trained and tested on separate cohorts; there was no additional training or learning involved. A generally healthy consecutive adult outpatient cohort of individuals without acute symptoms underwent low-dose unenhanced abdominopelvic CT scanning for routine colorectal cancer screening between 2004 and 2016 at a single medical center. Exclusion criteria included inadequate clinical follow-up (<1 year in the absence of a defined adverse event). The low-dose noncontrast supine multidetector CT scans used for this investigation were performed at a single center using the same general protocol on scanners from a single vendor (GE Healthcare Systems, Chicago, Ill), with 120 kVp and modulated tube current to achieve a noise index of 50, typically resulting in an effective dose of 2–3 mSv. Both 1.25 × 1 mm and 5 × 3 mm supine series were generated at the time of scanning. The specific additional colonography-related techniques for bowel preparation and colonic distention have been previously described (27,28) and are beyond the scope of this investigation. We have also investigated the use of automated CT tools for predicting the risk of future cardiovascular events and death in this cohort (29) as well as metabolic syndrome in a subcohort (30).

Automated CT Imaging Biomarkers

The deep learning and image processing algorithms used for this predictive trial were previously developed, trained, and tested. Specifically, the CT-based bone, muscle, and fat algorithms for automatically segmenting and quantifying the spine, abdominal musculature, and fat (visceral and subcutaneous) were all initially trained and tested on separate cohorts not used in our current study (22,31–34). In addition, we have published separate technical works focusing on each of these three tools (21,24,26), including success rates, normative values, and changes over time. The technical failure rates for these tools are all on the order of 1% or less. Both the preliminary works and this culminating predictive trial all made use of the computing capabilities of the NIH Biowulf system. Detailed specifics regarding the artificial intelligence method for automated CT-based anatomic tissue segmentation and quantification tools are described in these prior publications. Briefly, these tools fall into two main categories: a deep learning group and a feature-based image processing group. For bone and fat quantification, feature-based image processing algorithms were used, starting with fully automated spine segmentation and labeling software to identify each vertebral level from T12 to L5. This was followed by isolation of the anterior trabecular space of each vertebra for bone mineral density, as well as the visceral and subcutaneous fat compartments at each level. For the abdominal wall musculature, a deep learning algorithm consisting of a modified three-dimensional U-Net was used for segmentation and analysis.

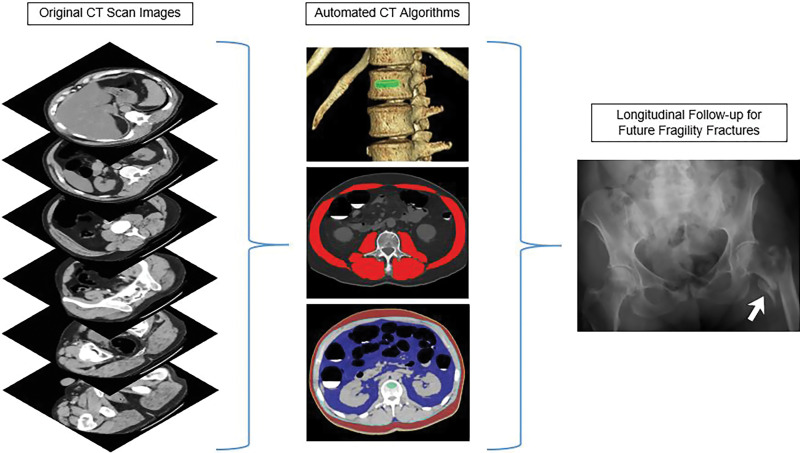

Each CT-based tissue measure can be reported in a variety of ways. Based on our prior work (21,24), measuring mean tissue attenuation of muscle and trabecular bone at defined vertebral levels (L3 and L1, respectively) using CT attenuation numbers measured in Hounsfield units was superior to measuring tissue bulk expressed by either cross-sectional area at defined levels or by volume. For adipose tissue assessment (26), we emphasized the ratio of visceral-to-subcutaneous (VS) fat at the L1 level. Therefore, we used the final selected tissue measures: L1-level trabecular attenuation for bone, L3-level abdominal wall muscle attenuation, and L1-level V/S fat ratio. Figure 1 depicts the process and visual correlates of the quantitative output for the automated CT tools. These CT-based biomarkers were derived from the screening cohort in a fully automated fashion. Because these validated CT-based tools were used in a static manner, whereby no additional learning was used, the need for additional training, testing, or cross-validation is obviated.

Figure 1:

Depiction of the fully automated CT imaging biomarker tools used to assess bone, muscle, and fat from the original abdominal CT scan data. In practice, one can review the visual tool outputs to allow for quality assurance of the automated segmentation results in individual patients. CT biomarkers results were then correlated with subsequent fragility fractures.

Clinical Parameters and Adverse Outcome Measures

The automated CT measures were compared with the FRAX fracture risk assessment calculator tool (https://www.sheffield.ac.uk/FRAX) for each patient (U.S. version), which provides a 10-year risk estimate for any fragility fracture as well as a separate estimate for hip fracture. Input variables were derived for FRAX scoring, including age, sex, height, weight, smoking history, previous fracture, and DXA femoral neck T-score, among others. We constructed an algorithmic electronic health record (EHR) search to extract all relevant available clinical data for each patient, using values closest in time to the CT scan; these values were then batch entered for FRAX calculation by a research assistant (P.M.G., 5 years of experience). Subset analysis was performed for those patients (n = 2106, 22.8%) with available DXA femoral neck T-scores for input, obtained using Lunar Prodigy densitometers (GE Healthcare Systems) within 2 years of CT examination. Body mass index (BMI) (in kilograms per meter squared) was also recorded for each patient. The adverse clinical outcome of interest was any major osteoporotic fracture occurring after CT scanning, defined as insufficiency fractures that are not related to high-impact trauma, including hip, spine, distal forearm, and proximal humerus. These were also systemically searched for by the automated EHR algorithm and confirmed by secondary review (P.M.G.). Given the increased morbidity and mortality related to femoral or hip fractures, this specific subset of fragility fractures was of particular interest.

Statistical Analysis

Summary statistics were compiled and compared for patients with and those without subsequent fragility fracture events. Relevant P values were derived using two-sided t tests for normally distributed variables, and the Wilcoxon rank sum test when the normality assumption did not hold. Area under the receiver operating characteristics (ROC) curve (AUC) comparisons were made using the DeLong method; P < .05 indicated statistical significance. To assess the association between the predictive measures and downstream adverse events, we used both an event-free survival analysis and logistic regression to compute ROC curves. For the time-to-event survival analysis, Kaplan-Meier curves were generated by splitting predictor variables into quartiles. Cox proportional hazards models were used to derive concordance values and individual risk predictions. For ROC curve analysis, data sets were restricted to defined time intervals (2, 5, and 10 years) because time to event is not considered. AUC with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated. Uni- and multivariable analyses of CT biomarkers were performed for comparison with the clinical reference standard (FRAX). Potential confounders of age and sex were considered in the ROC analysis as well as the addition of FRAX to the CT parameters. As described previously, FRAX is already a multivariable predictor. Hazard ratios with 95% CIs were computed for each predictor, comparing the highest-risk quartile against the other three quartiles. Missing input data elements in this final cohort of 9223 patients ranged from 0.3% to 1.4%, including L1 attenuation (n = 47), muscle attenuation (n = 28), V/S fat ratio (n = 133), FRAX (n = 123), and BMI (n = 123). We used R software (version 3.6) for statistical analyses.

Results

Patient Characteristics

Of 9305 healthy asymptomatic adults, 82 were excluded for inadequate clinical follow-up (<1 year in the absence of a defined adverse event). The final study cohort consisted of 9223 asymptomatic adults (mean age, 57 years ± 8 [standard deviation]; 5152 women, 4071 men).

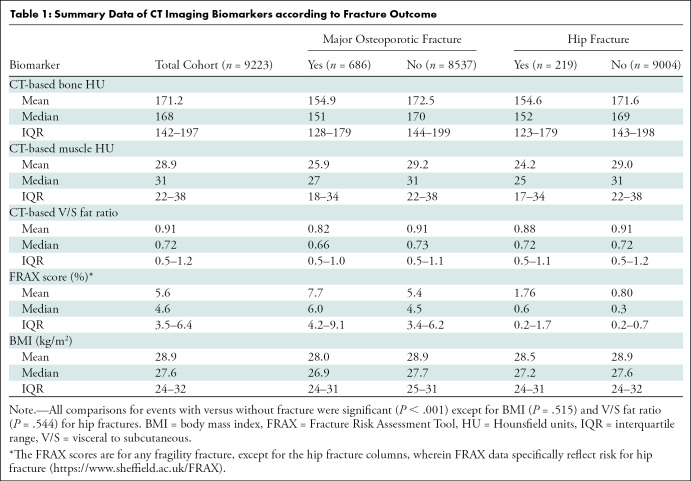

The median time of clinical follow-up beyond the CT scan was 8.8 years (interquartile range, 5.1–11.6 years). Subsequent fragility (major osteoporotic) fractures were documented in 686 (7.4%) patients, occurring an average of 5.8 years ± 3.6 (standard deviation) after CT scanning. The mean age (at CT) of patients who went on to experience fracture was 60 years compared with 57 years in those who did not experience fracture. Of those who experienced fracture, 69.7% (478 of 686) were women, compared with 54.7% (4674 of 8537) who did not experience fracture. Fracture prior to CT was identified in 4.8% (33 of 686) of patients who went on to subsequent fracture after CT scanning versus 2.7% (231 of 8532) who did not have a subsequent fracture (P = .002). Subsequent hip fractures were documented in 219 (2.4%) patients, occurring an average of 7.4 years ± 3.5 after CT scanning. Significant differences (P < .001) were observed for all measured parameters of interest between those with and those without a fragility fracture, except for the fat-based measures of BMI (P = .52) and V/S fat ratio (P = .54) for those with and those without a subsequent hip fracture (Table 1).

Table 1:

Summary Data of CT Imaging Biomarkers according to Fracture Outcome

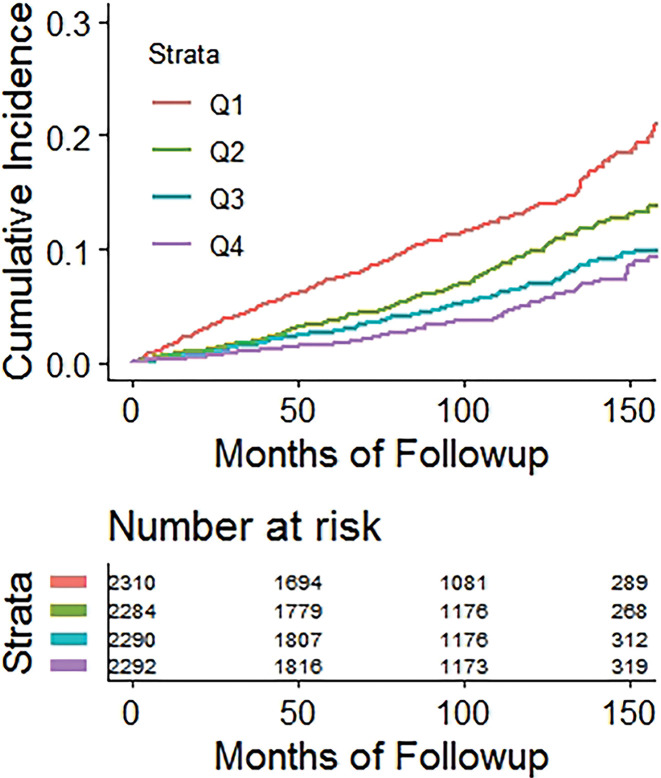

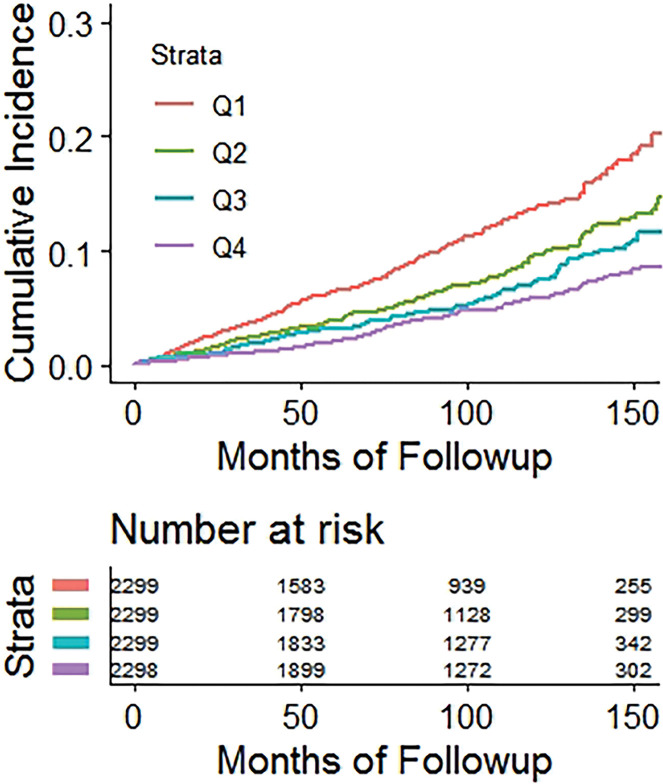

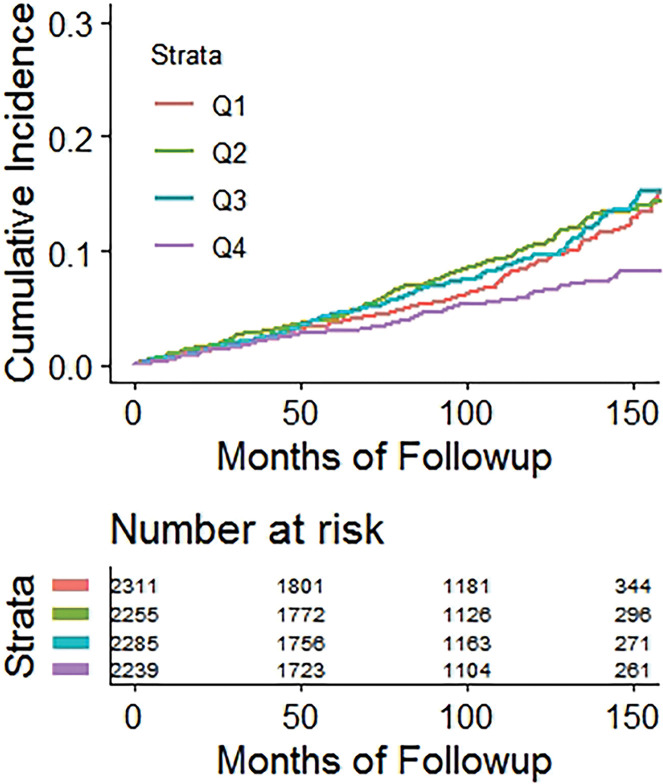

Diagnostic Performance of Automated CT-based Measures versus FRAX

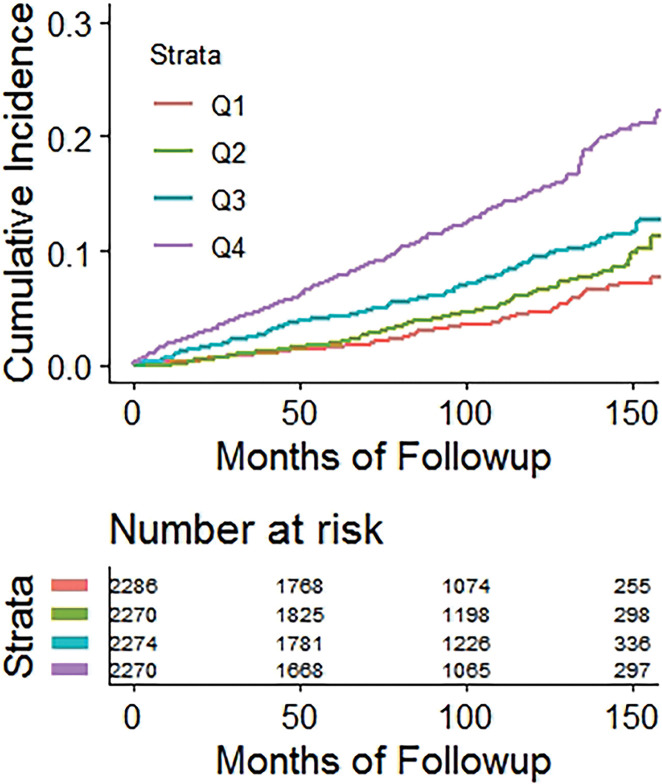

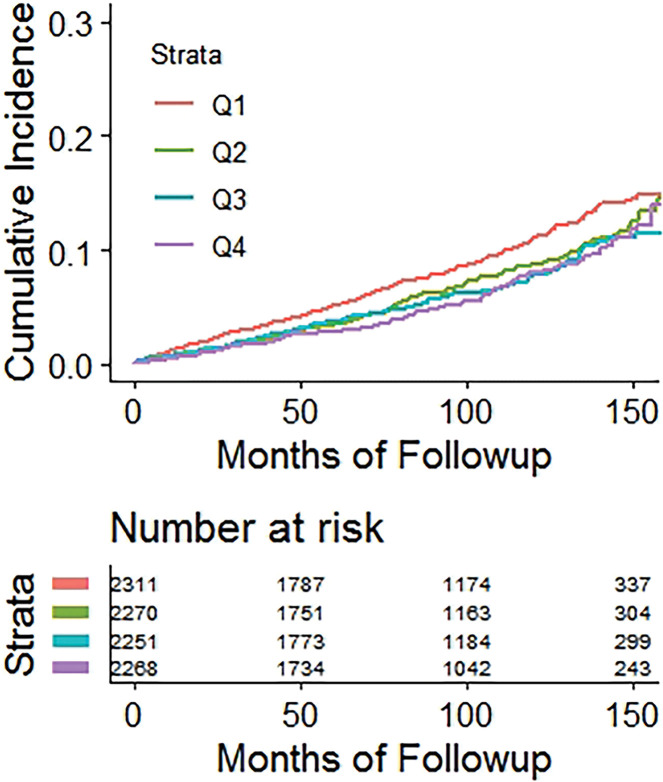

Kaplan-Meier time-to-fracture plots by quartile for FRAX, BMI, and the automated CT parameters of interest are shown in Figure 2. Reasonably good separation between quartiles over time was observed for FRAX, bone attenuation, and muscle attenuation, whereas quartile separation was much less pronounced for BMI and V/S fat ratio. However, there was some separation between the highest V/S ratio quartile (lower fracture rate) compared with the other three quartiles. Hazard ratios comparing the highest-risk quartile with the other three quartiles for L1-bone attenuation, L3-muscle attenuation, V/S fat ratio, and FRAX were 2.1 (95% CI: 1.8, 2.4), 1.9 (95% CI: 1.6, 2.2), 0.98 (95% CI: 0.82, 1.2), and 2.5 (95% CI: 2.1, 2.9), respectively, for any fragility fracture (all values P < .001 except V/S fat ratio, which was P = .78). For hip fractures, the corresponding hazard ratios for bone attenuation, muscle attenuation, V/S fat ratio, and FRAX were 2.0 (95% CI: 1.6, 2.7), 2.5 (95% CI: 1.9, 3.0), 1.1 (95% CI: 0.81, 1.5), and 2.5 (95% CI: 1.9, 3.3), respectively (all values P < .001 except V/S fat ratio, which was P = .51).

Figure 2a:

Kaplan-Meier time-to-fracture plots by quartile for the clinical and automated CT parameters. Separation between quartiles over time for future fragility fractures (n = 686) was observed for the automated CT parameters of (a) bone attenuation, (b) muscle attenuation, (c) visceral-to-subcutaneous (V/S) fat ratio, (d) Fracture Risk Assessment Tool (FRAX), and (e) body mass index (BMI). Quartile separation was much less pronounced for the fat-based measures (V/S ratio and BMI). However, the highest V/S quartile showed lower fracture incidence over time.

Figure 2b:

Kaplan-Meier time-to-fracture plots by quartile for the clinical and automated CT parameters. Separation between quartiles over time for future fragility fractures (n = 686) was observed for the automated CT parameters of (a) bone attenuation, (b) muscle attenuation, (c) visceral-to-subcutaneous (V/S) fat ratio, (d) Fracture Risk Assessment Tool (FRAX), and (e) body mass index (BMI). Quartile separation was much less pronounced for the fat-based measures (V/S ratio and BMI). However, the highest V/S quartile showed lower fracture incidence over time.

Figure 2c:

Kaplan-Meier time-to-fracture plots by quartile for the clinical and automated CT parameters. Separation between quartiles over time for future fragility fractures (n = 686) was observed for the automated CT parameters of (a) bone attenuation, (b) muscle attenuation, (c) visceral-to-subcutaneous (V/S) fat ratio, (d) Fracture Risk Assessment Tool (FRAX), and (e) body mass index (BMI). Quartile separation was much less pronounced for the fat-based measures (V/S ratio and BMI). However, the highest V/S quartile showed lower fracture incidence over time.

Figure 2d:

Kaplan-Meier time-to-fracture plots by quartile for the clinical and automated CT parameters. Separation between quartiles over time for future fragility fractures (n = 686) was observed for the automated CT parameters of (a) bone attenuation, (b) muscle attenuation, (c) visceral-to-subcutaneous (V/S) fat ratio, (d) Fracture Risk Assessment Tool (FRAX), and (e) body mass index (BMI). Quartile separation was much less pronounced for the fat-based measures (V/S ratio and BMI). However, the highest V/S quartile showed lower fracture incidence over time.

Figure 2e:

Kaplan-Meier time-to-fracture plots by quartile for the clinical and automated CT parameters. Separation between quartiles over time for future fragility fractures (n = 686) was observed for the automated CT parameters of (a) bone attenuation, (b) muscle attenuation, (c) visceral-to-subcutaneous (V/S) fat ratio, (d) Fracture Risk Assessment Tool (FRAX), and (e) body mass index (BMI). Quartile separation was much less pronounced for the fat-based measures (V/S ratio and BMI). However, the highest V/S quartile showed lower fracture incidence over time.

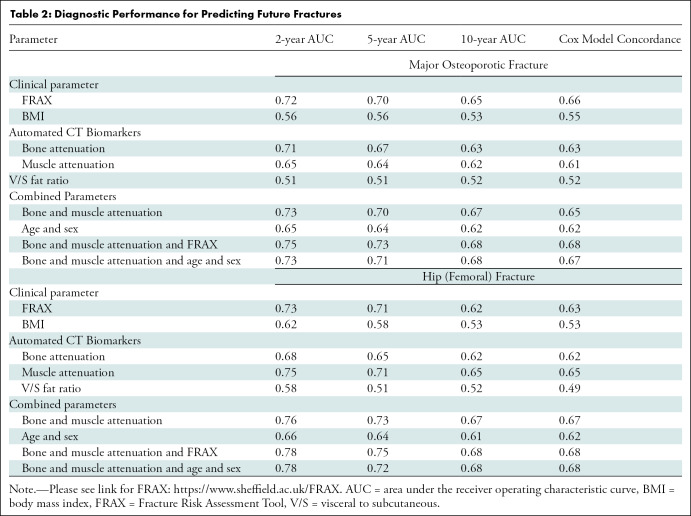

The diagnostic performance of FRAX and the automated CT markers according to ROC curve and Cox proportional hazards analyses for predicting any fragility fracture, and hip fractures specifically, are shown in Table 2. For predicting future osteoporotic fractures, the univariable performance of bone attenuation was comparable with that of the multivariable FRAX, with no difference (P ≥ .226). For example, the 2-year AUC (with 95% CI) for L1 attenuation was 0.71 (95% CI: 0.67, 0.76) compared with 0.72 (95% CI: 0.68, 77) for FRAX (Fig 3a). In comparison, the V/S fat ratio was a very poor predictor relative to FRAX (P < .001), with 2-year AUC of 0.51 (95% CI: 0.46, 0.56) (Fig 3a). When bone and muscle attenuation were combined, the 2-year AUC was 0.73 (95% CI: 0.68, 0.77) (Fig 3a) (P = .93). When FRAX was added to CT-based bone and muscle attenuation, the 2-year AUC did not significantly improve 0.75 (95% CI: 0.70, 0.80), (P = .19). When age and sex information were added to bone and muscle attenuation, no change was observed (AUC = 0.73). However, the CT measures added significantly to the ROC curve performance of age and sex alone (Table 2), with increased AUCs at 2-year (P = .027), 5-year (P = .004), and 10-year (P = .002) intervals. Subanalysis of the subset with DXA T-scores (n = 2106) showed that the FRAX performance actually decreased, whereas CT-based bone attenuation performance increased. For example, the 2-year AUC was 0.74 (95% CI: 0.67, 0.81) for CT-based bone attenuation and 0.65 (95% CI: 0.58, 0.73) for FRAX (P = .11).

Table 2:

Diagnostic Performance for Predicting Future Fractures

Figure 3a:

Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves for predicting future fragility fractures. (a) ROC curves for predicting any fragility fracture over a 2-year time horizon shows comparable performance between the univariable L1-bone attenuation (area under the ROC curve [AUC] = 0.71) and the multivariable Fracture Risk Assessment Tool (FRAX) (AUC = 0.72), whereas visceral-to-subcutaneous (V/S) fat ratio was a poor predictor (AUC = 0.51). When bone attenuation and muscle attenuation are combined, the performance improves slightly (AUC = 0.73). (b) ROC curves for predicting hip fractures over a 2-year time horizon show that the univariable muscle attenuation alone (AUC = 0.75) compares favorably with the multivariable FRAX (AUC = 0.73). When bone attenuation and muscle attenuation are combined (not shown), the performance is further improved, albeit only slightly (AUC = 0.76).

For hip fracture prediction (Table 2, Fig 3b), the univariable performance of muscle attenuation alone (0.75; 95% CI: 0.63, 0.86) was comparable with FRAX (0.73; 95% CI: 0.60, 0.86) in terms of 2-year AUC (P = .43). When bone and muscle attenuation were combined, the 2-year AUC for hip fracture prediction was 0.76 (95% CI: 0.67, 0.86; P = .73). When FRAX was added to CT-based bone and muscle measures, the 2-year AUC was 0.78 (95% CI: 0.68, 0.88; P = .757). Adding age and sex to the CT-based measures of bone and muscle again provided no change (AUC = 0.76).

Figure 3b:

Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves for predicting future fragility fractures. (a) ROC curves for predicting any fragility fracture over a 2-year time horizon shows comparable performance between the univariable L1-bone attenuation (area under the ROC curve [AUC] = 0.71) and the multivariable Fracture Risk Assessment Tool (FRAX) (AUC = 0.72), whereas visceral-to-subcutaneous (V/S) fat ratio was a poor predictor (AUC = 0.51). When bone attenuation and muscle attenuation are combined, the performance improves slightly (AUC = 0.73). (b) ROC curves for predicting hip fractures over a 2-year time horizon show that the univariable muscle attenuation alone (AUC = 0.75) compares favorably with the multivariable FRAX (AUC = 0.73). When bone attenuation and muscle attenuation are combined (not shown), the performance is further improved, albeit only slightly (AUC = 0.76).

Using the most widely accepted FRAX treatment threshold of 20% for 10-year fracture risk (for any fragility fracture), the corresponding sensitivity and specificity from our cohort was 4.1% (28 of 685) and 99.2% (8354 of 8425), respectively. From the 10-year ROC analysis for any fragility fracture, a CT-based L1-bone Hounsfield unit threshold of 123.5 HU had sensitivity and specificity of 22.3% and 90.0%, respectively. An L1-bone attenuation “optimal” threshold (by Youden index) of 148.5 HU had a corresponding sensitivity of 48.8% and specificity of 72.1%. A CT-based L3-muscle attenuation threshold of 16.2 HU also had a corresponding sensitivity and specificity of 22.3% and 90.0%, respectively, whereas a threshold of 27.3 HU had a sensitivity of 53.4% and a specificity of 67.1%. Similarly, using a FRAX hip fracture risk threshold of 3% had a sensitivity of 16.4% (35 of 214) and a specificity of 94.7% (8416 of 8886). From the 10-year ROC curve analysis for hip fracture, a CT-based bone attenuation threshold of 121.5 HU had a sensitivity and specificity of 33.9% and 90.1%, respectively. A bone attenuation threshold of 155.5 HU had a corresponding sensitivity of 66.1% and a specificity of 64.2%. A CT-based muscle attenuation threshold of 15.0 HU had a corresponding sensitivity and specificity of 20.7% and 90.0%, respectively, whereas a threshold of 25.8 HU had a sensitivity of 69.6% and a specificity of 69.2%.

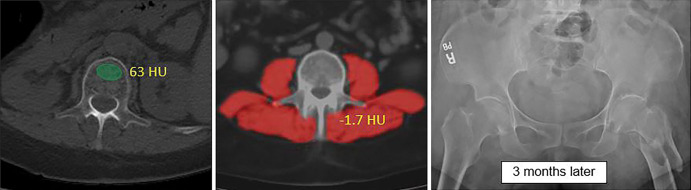

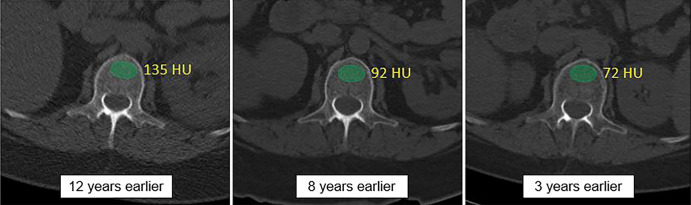

Figure 4 shows a patient with subsequent hip fracture that illustrates how the quantitative CT data could be applied in practice. In addition to very low bone and muscle attenuation, this patient also had prior CT examinations for unrelated clinical reasons that demonstrate how bone attenuation had been decreasing over time. However, this was not prospectively identified because this information generally goes unused in current routine clinical practice.

Figure 4a:

Individual example demonstrates the potential for CT-based fracture prediction. (a) Transverse nonenhanced CT images from a 59-year-old asymptomatic woman undergoing colonography for colorectal cancer screening. Automated bone (63 HU) and muscle (−1.7 HU) attenuation were at the 99th and 98th percentiles, respectively, relative to the screening study cohort, but Fracture Risk Assessment Tool scores of 6.7% (any fracture) and 0.5% (for hip fracture) were well below the recommended treatment threshold. However, she suffered a left femoral neck fracture only 3 months later. (b) The patient had multiple prior nonenhanced CT examinations for urolithiasis over the years, which in retrospect demonstrated progressive decrease in L1 bone attenuation (as shown). Unfortunately, this information is typically not yet considered in routine clinical practice for CT examinations performed for other indications.

Figure 4b:

Individual example demonstrates the potential for CT-based fracture prediction. (a) Transverse nonenhanced CT images from a 59-year-old asymptomatic woman undergoing colonography for colorectal cancer screening. Automated bone (63 HU) and muscle (−1.7 HU) attenuation were at the 99th and 98th percentiles, respectively, relative to the screening study cohort, but Fracture Risk Assessment Tool scores of 6.7% (any fracture) and 0.5% (for hip fracture) were well below the recommended treatment threshold. However, she suffered a left femoral neck fracture only 3 months later. (b) The patient had multiple prior nonenhanced CT examinations for urolithiasis over the years, which in retrospect demonstrated progressive decrease in L1 bone attenuation (as shown). Unfortunately, this information is typically not yet considered in routine clinical practice for CT examinations performed for other indications.

Discussion

Osteoporosis is a major public health issue that will only be further exacerbated by the general aging of the population (1–3). If those at greatest risk are not identified and treated, complicating osteoporotic fractures will result in substantial morbidity and mortality (35,36). Dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry (DXA) screening is the current imaging standard but remains underused. Similar to our cohort, only a minority of older adults (30% of women, 4% of men) reportedly undergo DXA screening in the United States (8), and Fracture Risk Assessment Tool (FRAX) is also similarly underused. Furthermore, DXA can be somewhat insensitive for fracture risk, as the majority of patients who suffer fragility fractures will not have an osteoporotic T score at DXA (7,11). CT represents an attractive additional solution, especially as an opportunistic add-on in unscreened individuals when performed for other clinical indications. As a cross-sectional imaging modality, CT can sample the vertebral trabecular space in a direct volumetric manner, without cortical overlay or other potential confounders. In addition, CT can provide potentially valuable assessment of other tissues, such as fat and muscle. Furthermore, automated tools for identifying prevalent vertebral fractures at CT are coming online, which will further improve identification of high-risk individuals (29,37). We have been applying manual opportunistic CT-based bone mineral density screening for a number of years now, both informally on the fly during body CT interpretation with L1 attenuation assessment and with more formal reporting of DXA-equivalent femoral neck T scores (10,38).

In our study of 9223 adults, we found that fully automated measurement of bone and muscle attenuation at abdominal CT provided comparable osteoporotic fracture risk prediction with the well-established yet underused and onerous clinical standard of FRAX. In the subset of patients screened with DXA (n = 2106), the predictive performance of FRAX (including T scores) actually decreased relative to the entire cohort (2-year AUC = 0.64 vs 0.72), whereas performance of CT-based bone measurement increased (2-year AUC = 0.74 vs 0.71). We also found that automated CT-based measures of muscle attenuation alone, without any bone-based assessment, provided similar prognostic ability for future hip fractures (2-year AUC = 0.75) as the multivariable FRAX (2-year AUC = 0.73). As such, these opportunistic CT measures need only be uni- or bivariable—and do not need to involve a long list of input variables that must be obtained and manually entered in the FRAX online calculator. In contrast, fat measures, whether via BMI or the more informative CT-based V/S ratio, had little or no prognostic value for future fragility fractures. Additionally, age and sex data, and even FRAX itself, added relatively little value to the CT-based bone and muscle measures alone.

Another group using different automated algorithms also recently showed the utility of opportunistic CT-based bone assessment for osteoporotic fracture risk assessment (12); however, they did not assess muscle or fat measurement. If the performance of these automated CT-based measures can be further confirmed by other groups and patient data sets, they could potentially even be incorporated into FRAX itself, providing another imaging alternative to DXA. Alternatively, as a standalone assessment, these CT-based measures could provide an automated predictor that would not require further manual input.

Our study further demonstrates the potential value of harnessing the rich biometric tissue data embedded within body CT scans that generally go unused in routine practice. Although the current investigation focused on future fragility fractures using bone, muscle, and fat data, we also used these in conjunction with automated quantification of vascular calcification and liver fat to predict the risk for major cardiovascular events and overall survival (29). We have also investigated the utility of these automated CT measures for metabolic syndrome and related clinical end points (30). As such, when coupled with an established screening indication such as CT colonography for colorectal cancer prevention, the additional benefit of CT-based cardiometabolic screening might further support the concept of standalone population-based CT screening of asymptomatic adults (29). That is, rather than the current opportunistic approach where the CT scan is performed for other clinical reasons, the cumulative value of the screening CT data itself might justify scanning.

Our study had limitations. All CT examinations were performed with a nonenhanced technique, and although these tools may perform similarly with contrast-enhanced scans (10), this has not yet been formally validated for these automated tools. This information is critical prior to widespread use in contrast-enhanced CT scans. Although we used a broad automated EHR search for FRAX inputs and other parameters, missing data elements related to the retrospective approach is possible. Furthermore, we used 2- and 5-year time horizons for ROC curve analysis, in addition to 10 years, given that clinical follow-up was less than a decade in many subjects. We acknowledge potential issues of selection bias with our healthy screening population that was generally younger and with less of a female predominance than is typical of osteoporosis screening. Application to an older symptomatic cohort would likely be of higher yield. In addition, further external validation of this automated method in separate patient cohorts with broader ethnic and racial diversity is warranted, as our cohort was about 90% White. Such a multi-institutional effort could be performed using a federated or other approach (39).

In conclusion, we have shown that fully automated quantitative tissue biomarkers of bone and muscle derived from abdominal CT scans provide similar predictive performance as the established multivariable Fracture Risk Assessment Tool (FRAX) for presymptomatic prediction of future fragility fractures. Muscle attenuation alone matched FRAX for future hip fracture prediction, whereas fat measures were poor predictors of fracture. These incidental CT-based measures could help capture some of the many unscreened individuals who are at increased yet unsuspected risk for osteoporotic fracture. This opportunistic approach leverages CT-based biometric data embedded in all abdominal scans and can add additional value to CT scans performed for other indications.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgments

This research was supported in part by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Clinical Center and utilized the high-performance computing capabilities of the NIH Biowulf cluster.

Disclosures of Conflicts of Interest: P.J.P. Activities related to the present article: disclosed no relevant relationships. Activities not related to the present article: advisor to Bracco and Zebra; is a shareholder in SHINE, Elucent, and Cellectar. Other relationships: disclosed no relevant relationships. P.M.G. disclosed no relevant relationships. R.Z. disclosed no relevant relationships. S.J.L. disclosed no relevant relationships. J.L. disclosed no relevant relationships. V.S. disclosed no relevant relationships. R.M.S. Activities related to the present article: disclosed no relevant relationships. Activities not related to the present article: receives royalties from iCAD, PingAn, Philips Translation Holdings, and ScanMed and research support from PingAn and NVIDIA. Other relationships: disclosed no relevant relationships.

Abbreviations:

- AUC

- area under the ROC curve

- BMI

- body mass index

- CI

- confidence interval

- DXA

- dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry

- FRAX

- Fracture Risk Assessment Tool

- ROC

- receiver operating characteristic

- V/S

- visceral to subcutaneous

References

- 1.Khosla S, Hofbauer LC. Osteoporosis treatment: recent developments and ongoing challenges. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 2017;5(11):898–907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Burge R, Dawson-Hughes B, Solomon DH, Wong JB, King A, Tosteson A. Incidence and economic burden of osteoporosis-related fractures in the United States, 2005-2025. J Bone Miner Res 2007;22(3):465–475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Roux C, Briot K. The crisis of inadequate treatment in osteoporosis. Lancet Rheumatol 2020;2(2):e110–e119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Haentjens P, Magaziner J, Colón-Emeric CS, et al. Meta-analysis: excess mortality after hip fracture among older women and men. Ann Intern Med 2010;152(6):380–390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kanis JA, Johnell O, Oden A, Johansson H, McCloskey E. FRAX and the assessment of fracture probability in men and women from the UK. Osteoporos Int 2008;19(4):385–397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kanis JA, Harvey NC, Cooper C, et al. A systematic review of intervention thresholds based on FRAX. Arch Osteoporos 2016;11(1):25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Siris ES, Chen YT, Abbott TA, et al. Bone mineral density thresholds for pharmacological intervention to prevent fractures. Arch Intern Med 2004;164(10):1108–1112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Curtis JR, Carbone L, Cheng H, et al. Longitudinal trends in use of bone mass measurement among older Americans, 1999-2005. J Bone Miner Res 2008;23(7):1061–1067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Edwards MH, Dennison EM, Aihie Sayer A, Fielding R, Cooper C. Osteoporosis and sarcopenia in older age. Bone 2015;80:126–130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jang S, Graffy PM, Ziemlewicz TJ, Lee SJ, Summers RM, Pickhardt PJ. Opportunistic osteoporosis screening at routine abdominal and thoracic CT: normative L1 trabecular attenuation values in more than 20 000 adults. Radiology 2019;291(2):360–367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pickhardt PJ, Pooler BD, Lauder T, del Rio AM, Bruce RJ, Binkley N. Opportunistic screening for osteoporosis using abdominal computed tomography scans obtained for other indications. Ann Intern Med 2013;158(8):588–595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dagan N, Elnekave E, Barda N, et al. Automated opportunistic osteoporotic fracture risk assessment using computed tomography scans to aid in FRAX underutilization. Nat Med 2020;26(1):77–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lee SJ, Graffy PM, Zea RD, Ziemlewicz TJ, Pickhardt PJ. Future osteoporotic fracture risk related to lumbar vertebral trabecular attenuation measured at routine body CT. J Bone Miner Res 2018;33(5):860–867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pickhardt PJ, Bodeen G, Brett A, Brown JK, Binkley N. Comparison of femoral neck BMD evaluation obtained using Lunar DXA and QCT with asynchronous calibration from CT colonography. J Clin Densitom 2015;18(1):5–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ziemlewicz TJ, Maciejewski A, Binkley N, Brett AD, Brown JK, Pickhardt PJ. Opportunistic quantitative CT bone mineral density measurement at the proximal femur using routine contrast-enhanced scans: direct comparison with DXA in 355 adults. J Bone Miner Res 2016;31(10):1835–1840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rajkomar A, Dean J, Kohane I. Machine learning in medicine. N Engl J Med 2019;380(14):1347–1358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Linguraru MG, Richbourg WJ, Liu J, et al. Tumor burden analysis on computed tomography by automated liver and tumor segmentation. IEEE Trans Med Imaging 2012;31(10):1965–1976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Choy G, Khalilzadeh O, Michalski M, et al. Current applications and future impact of machine learning in radiology. Radiology 2018;288(2):318–328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dreyer KJ, Geis JR. When machines think: radiology’s next frontier. Radiology 2017;285(3):713–718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Moreno CC, Hemingway J, Johnson AC, Hughes DR, Mittal PK, Duszak R, Jr. Changing abdominal imaging utilization patterns: perspectives from Medicare beneficiaries over two decades. J Am Coll Radiol 2016;13(8):894–903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pickhardt PJ, Lee SJ, Liu J, et al. Population-based opportunistic osteoporosis screening: validation of a fully automated CT tool for assessing longitudinal BMD changes. Br J Radiol 2019;92(1094):20180726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Summers RM, Baecher N, Yao J, et al. Feasibility of simultaneous computed tomographic colonography and fully automated bone mineral densitometry in a single examination. J Comput Assist Tomogr 2011;35(2):212–216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Graffy PM, Sandfort V, Summers RM, Pickhardt PJ. Automated liver fat quantification at nonenhanced abdominal CT for population-based steatosis assessment. Radiology 2019;293(2):334–342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Graffy PM, Liu J, Pickhardt PJ, Burns JE, Yao J, Summers RM. Deep learning-based muscle segmentation and quantification at abdominal CT: application to a longitudinal adult screening cohort for sarcopenia assessment. Br J Radiol 2019;92(1100):20190327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Graffy PM, Liu J, O’Connor S, Summers RM, Pickhardt PJ. Automated segmentation and quantification of aortic calcification at abdominal CT: application of a deep learning-based algorithm to a longitudinal screening cohort. Abdom Radiol (NY) 2019;44(8):2921–2928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lee SJ, Liu J, Yao J, Kanarek A, Summers RM, Pickhardt PJ. Fully automated segmentation and quantification of visceral and subcutaneous fat at abdominal CT: application to a longitudinal adult screening cohort. Br J Radiol 2018;91(1089):20170968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pickhardt PJ, Choi JR, Hwang I, et al. Computed tomographic virtual colonoscopy to screen for colorectal neoplasia in asymptomatic adults. N Engl J Med 2003;349(23):2191–2200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kim DH, Pickhardt PJ, Taylor AJ, et al. CT colonography versus colonoscopy for the detection of advanced neoplasia. N Engl J Med 2007;357(14):1403–1412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pickhardt PJ, Graffy PM, Zea R, et al. Automated CT biomarkers for opportunistic prediction of future cardiovascular events and mortality in an asymptomatic screening population. Lancet Digit Health 2020;2(4):e192–e200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pickhardt PJ, Graffy PM, Zea R, et al. Opportunistic screening for metabolic syndrome in asymptomatic adults utilizing fully automated abdominal CT-based biomarkers. AJR Am J Roentgenol (in press). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 31.Burns JE, Yao J, Chalhoub D, Chen JJ, Summers RM. A Machine learning algorithm to estimate sarcopenia on abdominal CT. Acad Radiol 2020;27(3):311–320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sandfort V, Yan K, Pickhardt PJ, Summers RM. Data augmentation using generative adversarial networks (CycleGAN) to improve generalizability in CT segmentation tasks. Sci Rep 2019;9(1):16884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yao J, Burns JE, Forsberg D, et al. A multi-center milestone study of clinical vertebral CT segmentation. Comput Med Imaging Graph 2016;49:16–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yao JH, O’Connor SD, Summers RM. Automated spinal column extraction and partitioning. In: 2006 3rd IEEE International Symposium on Biomedical Imaging: Macro to Nano, Vols 1-3. Piscataway, NJ: IEEE, 2006; 390–393. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Khosla S, Shane E. A crisis in the treatment of osteoporosis. J Bone Miner Res 2016;31(8):1485–1487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Miller PD. Underdiagnosis and undertreatment of osteoporosis: the battle to be won. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2016;101(3):852–859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Burns JE, Yao J, Summers RM. Vertebral body compression fractures and bone density: automated detection and classification on CT images. Radiology 2017;284(3):788–797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ziemlewicz TJ, Binkley N, Pickhardt PJ. Opportunistic osteoporosis screening: addition of quantitative CT bone mineral density evaluation to CT colonography. J Am Coll Radiol 2015;12(10):1036–1041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yang Q, Liu Y, Chen TJ, Tong YX. Federated machine learning: concept and applications. ACM Trans Intell Syst Technol 2019;10(2):12. [Google Scholar]

![Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves for predicting future fragility fractures. (a) ROC curves for predicting any fragility fracture over a 2-year time horizon shows comparable performance between the univariable L1-bone attenuation (area under the ROC curve [AUC] = 0.71) and the multivariable Fracture Risk Assessment Tool (FRAX) (AUC = 0.72), whereas visceral-to-subcutaneous (V/S) fat ratio was a poor predictor (AUC = 0.51). When bone attenuation and muscle attenuation are combined, the performance improves slightly (AUC = 0.73). (b) ROC curves for predicting hip fractures over a 2-year time horizon show that the univariable muscle attenuation alone (AUC = 0.75) compares favorably with the multivariable FRAX (AUC = 0.73). When bone attenuation and muscle attenuation are combined (not shown), the performance is further improved, albeit only slightly (AUC = 0.76).](https://cdn.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/blobs/2f61/7526945/cd7638147f8c/radiol.2020200466.fig3a.jpg)

![Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves for predicting future fragility fractures. (a) ROC curves for predicting any fragility fracture over a 2-year time horizon shows comparable performance between the univariable L1-bone attenuation (area under the ROC curve [AUC] = 0.71) and the multivariable Fracture Risk Assessment Tool (FRAX) (AUC = 0.72), whereas visceral-to-subcutaneous (V/S) fat ratio was a poor predictor (AUC = 0.51). When bone attenuation and muscle attenuation are combined, the performance improves slightly (AUC = 0.73). (b) ROC curves for predicting hip fractures over a 2-year time horizon show that the univariable muscle attenuation alone (AUC = 0.75) compares favorably with the multivariable FRAX (AUC = 0.73). When bone attenuation and muscle attenuation are combined (not shown), the performance is further improved, albeit only slightly (AUC = 0.76).](https://cdn.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/blobs/2f61/7526945/18d5f1ebfbce/radiol.2020200466.fig3b.jpg)