Various host cell factors facilitate critical steps in the HIV-1 replication cycle. One of these factors is myo-inositol hexaphosphate (IP6), which contributes to assembly of HIV-1 immature particles and helps maintain the well-balanced metastability of the core in the mature infectious virus. Using a combination of two in vitro methods to monitor assembly of immature HIV-1 particles and disassembly of the mature core-like structure, we quantified the contribution of IP6 and other small polyanion molecules to these essential steps in the viral life cycle. Our data showed that IP6 contributes substantially to increasing the assembly of HIV-1 immature particles. Additionally, our analysis confirmed the important role of two HIV-1 capsid lysine residues involved in interactions with IP6. We found that myo-inositol hexasulphate also stabilized the HIV-1 mature particles in a concentration-dependent manner, indicating that targeting this group of small molecules may have therapeutic potential.

KEYWORDS: HIV-1, IP6, assembly, capsid, immature, mature, polyanion

ABSTRACT

Proper assembly and disassembly of both immature and mature HIV-1 hexameric lattices are critical for successful viral replication. These processes are facilitated by several host-cell factors, one of which is myo-inositol hexaphosphate (IP6). IP6 participates in the proper assembly of Gag into immature hexameric lattices and is incorporated into HIV-1 particles. Following maturation, IP6 is also likely to participate in stabilizing capsid protein-mediated mature hexameric lattices. Although a structural-functional analysis of the importance of IP6 in the HIV-1 life cycle has been reported, the effect of IP6 has not yet been quantified. Using two in vitro methods, we quantified the effect of IP6 on the assembly of immature-like HIV-1 particles, as well as its stabilizing effect during disassembly of mature-like particles connected with uncoating. We analyzed a broad range of molar ratios of protein hexamers to IP6 molecules during assembly and disassembly. The specificity of the IP6-facilitated effect on HIV-1 particle assembly and stability was verified by K290A, K359A, and R18A mutants. In addition to IP6, we also tested other polyanions as potential assembly cofactors or stabilizers of viral particles.

IMPORTANCE Various host cell factors facilitate critical steps in the HIV-1 replication cycle. One of these factors is myo-inositol hexaphosphate (IP6), which contributes to assembly of HIV-1 immature particles and helps maintain the well-balanced metastability of the core in the mature infectious virus. Using a combination of two in vitro methods to monitor assembly of immature HIV-1 particles and disassembly of the mature core-like structure, we quantified the contribution of IP6 and other small polyanion molecules to these essential steps in the viral life cycle. Our data showed that IP6 contributes substantially to increasing the assembly of HIV-1 immature particles. Additionally, our analysis confirmed the important role of two HIV-1 capsid lysine residues involved in interactions with IP6. We found that myo-inositol hexasulphate also stabilized the HIV-1 mature particles in a concentration-dependent manner, indicating that targeting this group of small molecules may have therapeutic potential.

INTRODUCTION

An immature HIV-1 particle is formed by approximately 2,500 Gag polyprotein precursors, which are arranged radially inside the particle with the C termini facing the particle center (1). HIV-1 Gag consists of four domains—matrix (MA, p17), capsid (CA, p24), nucleocapsid (NC), and p6—and two short peptide sequences linking CA and NC (spacer peptide 1, SP1) and NC and p6 (spacer peptide 2, SP2). Assembly of HIV-1 is initiated in the cytoplasm by specific interactions between dimeric viral genomic RNA (gRNA) and a few molecules of Gag polyprotein, namely, its NC domain (2, 3). Targeting of the Gag-RNA complex to the plasma membrane (PM) is facilitated by the MA domain of Gag. Due to its N-terminal covalently linked myristoyl group and a cluster of basic amino acids, HIV-1 MA recognizes and binds to PI(4,5)P2 in the cytoplasmic membrane (4–7). To assemble an immature particle, the membrane-bound Gag polyprotein starts to multimerize, driven mainly by a third structurally important Gag domain, CA. CA-facilitated multimerization on the inner leaflet of the PM leads to the formation of the hexameric lattice of an immature particle. Under the assistance of the cellular endosomal sorting complex required for transport (ESCRT), the immature particle buds and is released into the extracellular environment. The transition from an immature to mature HIV-1 particle is triggered by activation of virus-encoded protease. Proteolytic cleavage of Gag polyproteins into individual viral proteins leads to reorganization of the particle interior. MA proteins remain bound to the membrane, while a portion of CA proteins (approximately 1,500 molecules) reassemble to form a mature core, protecting the NC:gRNA complex. The mature HIV-1 hexameric lattice is formed by about 250 CA hexamers with 12 incorporated pentamers (8–11). These pentamers allow the formation of the closed conical core characteristic of HIV-1 (9, 12).

Although both immature and mature HIV-1 lattices are built from Gag or CA hexamers, the interhexameric and intrahexameric contacts, mediated by the CA domain or CA protein, differ. CA has two globular subdomains: an N-terminal domain (NTD) consisting of an N-terminal β-hairpin and seven α-helices and a C-terminal domain (CTD), which is composed of a major homology region (MHR) and four α-helices. CA-NTD determines the morphology of the immature particle, while CA-CTD plays a central role in immature hexameric lattice formation and stabilization (13, 14). CA-CTD facilitates the connection of two hexamers by homo-dimeric interactions in helix 9, especially by amino acid residues W316 and M317, and the MHR residues contribute to hexamer stability (14, 15). A segment of 14 amino acids called the SP1 domain lies downstream of CA-CTD. In an immature particle, the C-terminal residues (356 to 371) of CA-CTD and first eight residues of SP1 form a six-helix bundle (6HB), which is crucial for assembly and stability of the HIV-1 Gag hexameric lattice (16–18). Within individual hexamers in the immature lattice, CA-CTD and 6HB form a goblet-like structure (17–19). During HIV-1 protease-mediated Gag processing, cleavage in 6HB likely disrupts this structure, liberating mature CA proteins that assemble into the mature cone-shaped core. Similarly to the immature lattice, CA-CTD dimerization in the mature lattice is mediated by helix 9. However, liberating CA at both termini (the N terminus by MA-CA-NTD cleavage and the C terminus by CA-CTD-SP1 cleavage) leads to a rearrangement of CA-NTD, which subsequently mediates the main hexamer stabilizing interactions (9, 14, 20–22). Inter- and intrahexameric interactions of the CA subdomains mediate appropriate, well-balanced stability of the core, which is crucial for all subsequent steps of the HIV-1 life cycle (20, 22, 23). A ring of six positively charged arginine residues (R18) lies at the 6-fold symmetry axis interface at the center of each mature CA hexamer. This electropositive R18 pore was recently shown to selectively bind nucleotides or polyanions such as hexacarboxybenzene (24). HIV-1 core stability is affected by the presence of various host cell factors that are recruited and bind inside the pocket formed by the CA-NTD and CA-CTD interface (25, 26).

Recently, the negatively charged small molecule myo-inositol hexaphosphate (IP6) was reported to facilitate assembly of 6HB in the immature Gag lattice (27). Following Gag maturation, IP6 also promotes the formation of the mature core by binding to R18 residues in the electropositive pore (28). Even though inositol phosphate had previously been reported to modulate in vitro assembly of immature particles (29, 30), the structural aspects and its role as a Gag assembly cofactor were described by Dick et al. (27). He and his colleagues found that IP6 is bound in 6HB via interactions with the side chains of two lysine residues: K290, situated in MHR, and K359, located at the top of 6HB. Structural studies of the CA-SP1 region, resolved at 3.9 Å by cryo-EM and 3.27 Å by crystal structure, showed that these two lysine residues create a ring with a diameter corresponding to the size of the IP6 molecule (17, 18). IP6 likely stabilizes 6HB and promotes Gag hexamer formation (27). In vitro analysis has shown that inositol phosphates other than IP6 can also promote assembly of immature HIV-1 particles (27, 29). The effect on HIV-1 assembly is enhanced with increasing numbers of substituents, especially phosphate groups, on the myo-inositol scaffold (27, 29). In mature particles, IP6 binds inside the R18 pore, regulating the core stability (27, 28). While the half-life of HIV-1 cores without IP6 was approximately 7 min, the addition of 10 or 100 μM IP6 prolonged the half-life of authentic HIV-1 cores to 5 or 10 h. One hypothesis is that IP6 neutralizes the positive charge of the R18 pore and thus stabilizes the hexamer (28). Recently, by adjusting IP6 levels in cells and viruses, Mallery et al. showed the critical role of IP6 in HIV-1 replication (31).

Although IP6 is a crucial host factor for HIV-1, its effects on the assembly and stability of immature and mature particles have not yet been quantified in detail. Previous studies of the effect of IP6 relied on transmission electron microscopy (27–29), reverse transcription assays, and crystallization (28). These methods provided valuable insight into the effect of IP6 on HIV-1 core stabilization and assembly facilitation, but are not quantitative. Using our previously established in vitro methods FAITH and DITH (Fast Assembly Inhibitor Test for HIV and Disassembly Inhibitor Test for HIV, respectively), we quantified the impact of IP6 on the assembly and stability of both immature and mature-like HIV-1 particles in vitro (32, 33). In addition to IP6, we determined the effect of other polyanions, including myo-inositol (myo-In), glucose-1,6-bisphosphate (G-2P), myo-inositol hexasulphate (IS6), and mellitic acid (MeA). Our data clearly revealed that HIV-1 prefers IP6 as a cofactor during assembly of immature-like particles and as a stabilizer of mature-like particles. Moreover, we confirmed that the optimal ratio of protein hexamer to IP6 to facilitate assembly of the immature lattice is between 1:1 and 1:2. Interestingly, a ratio of 1:0.12 was most effective in increasing the stability of mature-like particles. To verify the binding site of IP6 in immature and mature particles, we prepared two mutant CA proteins: (i) one in which K290 and K359, responsible for the binding of IP6 to the immature particles, were substituted with alanines; and (ii) one in which R18, which mediates the interactions with the hexameric lattice in the mature core, was substituted with alanine. Using FAITH and DITH, we screened a broad range of IP6 concentrations and other factors to determine their effect on the efficacy of HIV-1 particle assembly and stability.

RESULTS

Assembly of HIV-1 Gag-derived proteins used in in vitro quantification assays.

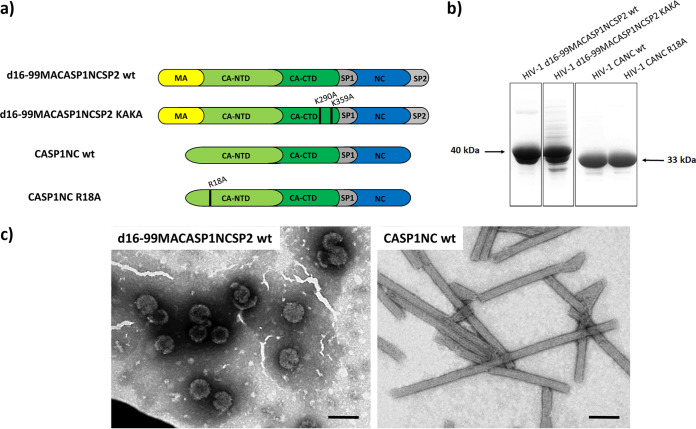

To quantify the effect of small molecules on HIV-1 assembly, particularly on the particle formation and stability, we used two assays: FAITH and DITH (32, 33). These assays are based on the ability of HIV-1 Gag-derived proteins to bind a short oligonucleotide and assemble immature- or mature-like particles. The addition of a fluorescent dye (FAM) and its quencher (BHQ) to the 5′ end of the short oligonucleotide (tqON) enables quantification of amount of tqON protected against Exonuclease I. As the binding of the nucleocapsid domain is not sufficient to protect tqON against exonuclease cleavage, given the assembly of the protective protein shell is required, FAITH in combination with TEM analysis allows us to determine the effect of various compounds and substances on the assembly (32, 33). This effect we describe here as assembly efficiency. In vitro assembly of immature-like particles was achieved using HIV-1 d16-99MACASP1NCSP2 protein, while mature-like particles were assembled using HIV-1 CASP1NC protein (Fig. 1a). These HIV-1 Gag-derived proteins were purified as previously described (32–35) (Fig. 1b). Their ability to assemble upon incubation with a dually labeled short oligonucleotide (40-mer, tqON) was verified by TEM (Fig. 1c).

FIG 1.

HIV-1 Gag-derived proteins used in this study. (a) Schematic representation of HIV-1 d16-99MACASP1NCSP2 wt and CASP1NC wt. (b) Coomassie brilliant blue-stained SDS polyacrylamide gels of purified HIV-1 Gag derived proteins. (c) TEM analysis of negatively stained HIV-1 d16-99MACASP1NCSP2 and CASP1NC proteins assembled in the presence of tqON in assembly buffer. Bars represent 200 nm.

The effect of IP6 on assembly of HIV-1 immature-like particles.

First, we tested the effect of IP6 on the formation of HIV-1 immature-like particles. IP6 was added at various concentrations (0.3 to 5 μM) during assembly of d16-99MACASP1NCSP2 particles. As IP6 is supposed to interact with a protein hexamer, we used IP6 concentrations corresponding to hexamer:IP6 ratios ranging from 1:0.12 to 1:2.00. Upon incubation, Exonuclease I was added to each sample and the released fluorescence was measured. In addition, the assembled material was negatively stained and analyzed by TEM.

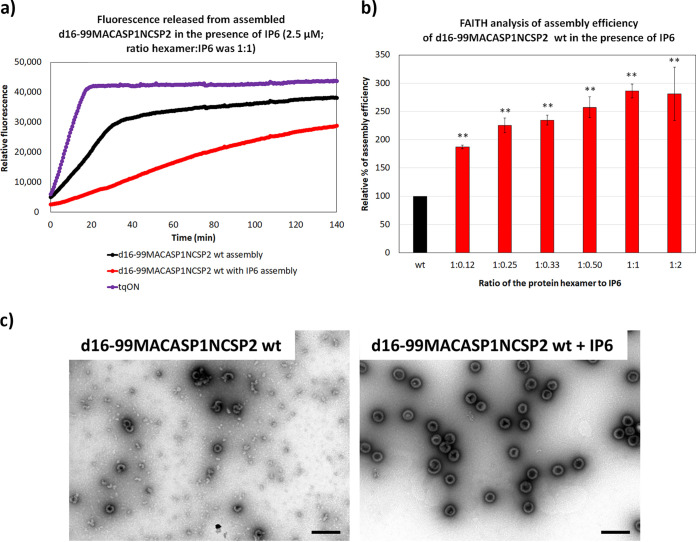

FAITH analysis demonstrated that the presence of IP6 in the assembly reaction increased the efficiency of immature-like HIV-1 particle assembly in a concentration-dependent manner (Fig. 2a and b, Fig. 3). The highest assembly efficiencies were observed at protein hexamer:IP6 ratios between 1:1 and 1:2. At these molar ratios, assembly efficacy was three times higher than without the addition of IP6. TEM analysis showed an increase in fully assembled spherical immature-like HIV-1 particles in samples containing IP6 (Fig. 2c). The diameters of virus-like particles (VLPs) assembled in the presence of IP6 were about 10% larger (from 86 to 109 nm) than those of particles formed in the absence of IP6 (diameters in the range of 77 to 100 nm) (Fig. 4d).

FIG 2.

Assembly efficiency of HIV-1 d16-99MACASP1NCSP2 in the presence of IP6 analyzed by FAITH and TEM. (a) Fluorescence emission curves demonstrating the kinetics of tqON degradation by ExoI; tqON (violet curve); tqON release from assembled d16-99MACASP1NCSP2 particles incubated in the absence of IP6 (black curve); presence of IP6 at final concentration 2.5 μM, corresponding protein hexamer:IP6 ratio was 1:1 (red curve). (b) Percentage of d16-99MACASP1NCSP2 wt assembly efficiency in the presence of increasing concentrations of IP6 (red columns) corresponding to the indicated ratios of hexamer:IP6 ratio compared to d16-99MACASP1NCSP2 wt in the absence of IP6 (black column). (c) TEM analysis of negatively stained HIV-1 d16-99MACASP1NCSP2 protein assembled in the absence (left) or the presence (right) of IP6 at a final concentration of 2.5 μM, corresponding to the protein hexamer:IP6 ratio of 1:1. Bars represent 200 nm. P values were assessed by ANOVA using the Tukey-Kramer test (**, P < 0.01).

FIG 3.

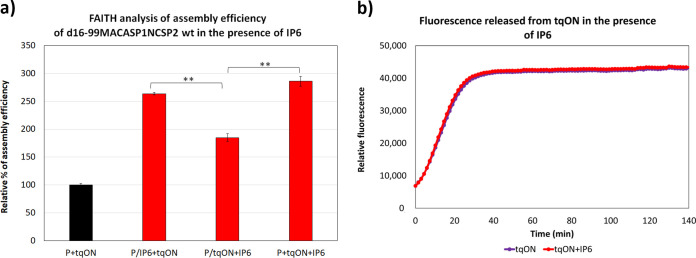

Effect of IP6 on FAITH arrangement and ExoI activity. (a) FAITH analysis of assembly efficiency of HIV-1 d16-99MACASP1NCSP2 protein (P) incubated in the presence of tqON (P+tqON, black column) or in the presence of IP6 at a final concentration of 2.5 μM (red columns). P was preincubated with IP6 (P/IP6+tqON) or tqON (P/tqON+IP6) for 1 h before the addition of tqON or IP6, respectively. Finally, tqON and IP6 were added simultaneously to P (P+tqON+IP6). (b) Fluorescence emission curves demonstrating the kinetics of tqON degradation in the absence (black curve) or presence (red curve) of IP6 at a final concentration of 2.5 μM. P values were assessed by ANOVA using the Tukey-Kramer test (**, P < 0.01).

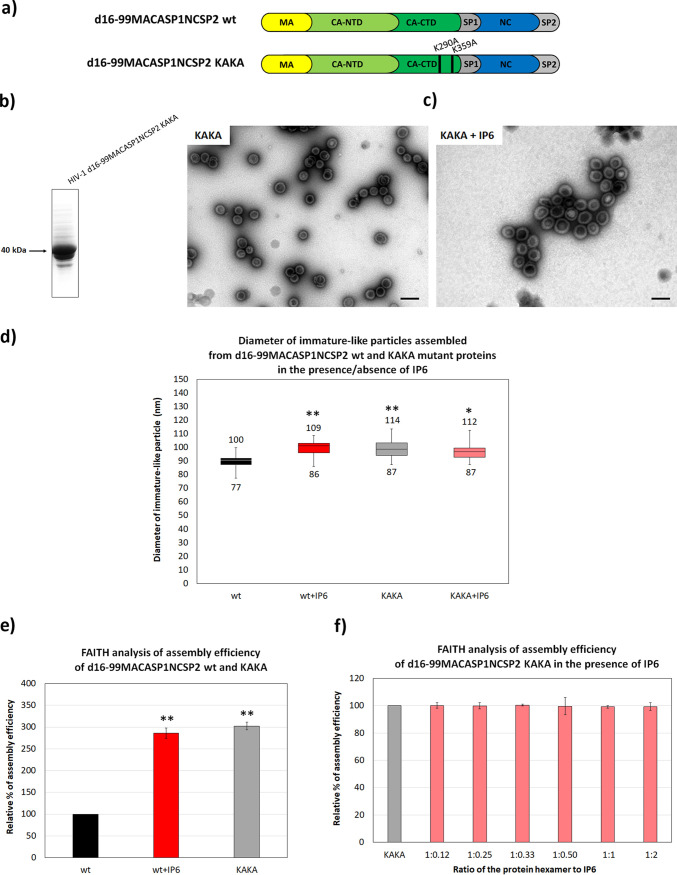

FIG 4.

Assembly efficiency of KAKA mutant of HIV-1 d16-99MACASP1NCSP2 protein in the absence or presence of IP6. (a) Schematic representation of HIV-1 d16-99MACASP1NCSP2 wt and KAKA mutants. (b) Coomassie brilliant blue-stained SDS polyacrylamide gel of purified HIV-1 d16-99MACASP1NCSP2 KAKA. (c) TEM analysis of negatively stained KAKA mutant assembled in the absence (left panel) or presence (right panel) of IP6 at a final concentration of 2.5 μM, corresponding to the CA hexamer ratio:PA of 1:1. Bars represent 200 nm. (d) Diameters of immature VLPs assembled from wt and KAKA d16-99MACASP1NCSP2 proteins in the absence or presence of IP6 (2.5 μM). (e) Percentage of assembly efficiency of d16-99MACASP1NCSP2 wt in the absence (black column) or presence of IP6 (2.5 μM) (red column) compared to the KAKA mutant (gray column) in the absence of IP6. (f) Percentage of assembly efficiency of KAKA mutant in the absence (gray column) and presence of different concentrations of IP6 (salmon columns) corresponding to the indicated protein hexamer:IP6 ratio. P values were assessed by ANOVA using the Tukey-Kramer test (*, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01).

Like a DNA oligonucleotide, IP6 has a negative charge. During assembly, tqON is mainly incorporated by nonspecific electrostatic interactions with NC lysine or arginine residues. Thus, it is plausible that IP6 competed with tqON for binding to NC and thereby biased the FAITH results. To analyze this, we tested three arrangements of assembly reactions: (i) both IP6 and tqON were added simultaneously to d16-99MACASP1NCSP2 wild-type (wt) protein and incubated for 3 h (Fig. 3a, P+tqON+IP6); (ii) d16-99MACASP1NCSP2 wt was preincubated with tqON for 1 h before IP6 was added (Fig. 3a, P/tqON+IP6) and the sample was incubated for 3 h; and (iii) d16-99MACASP1NCSP2 wt was preincubated with IP6 for 1 h before tqON was added (Fig. 3a, P/IP6+tqON) and the sample incubation continued for 3 h. Following the 3-h incubation, exonuclease I was added and the released fluorescence was measured.

Simultaneous IP6 and tqON addition (Fig. 3a, red column P+tqON+IP6) increased the assembly efficiency almost 3-fold compared to a control lacking IP6 (Fig. 3a, black column P+tqON). Preincubation of HIV-1 d16-99MACASP1NCSP2 protein with IP6 did not significantly affect the binding of tqON to NC, and only a minor decrease in assembly efficiency was observed compared with simultaneous IP6/tqON addition (Fig. 3a, red columns P/IP6+tqON and P+tqON+IP6). When following preincubation with tqON, IP6 was added to the assembled particles (Fig. 3a, red column P/tqON+IP6), the assembly efficiency was still 1.7-fold higher than for the sample without IP6, but significantly lower than for the two other samples. In addition, IP6 at any tested concentration did not affect the activity of ExoI or the fluorescence of tqON (Fig. 3b).

Dick et al. reported that the effect of IP6 on immature HIV-1 particle assembly is triggered by two lysine residues in HIV-1 CA-CTD: K290 and K359 (27). K290 is in the major homology region (MHR), while K359 is localized near the carboxy terminus of CA, which, together with the SP1 region, forms a six-helix bundle (6HB) structure. To verify that the increase in d16-99MACASP1NCSP2 assembly efficacy observed in the presence of IP6 was due to interactions between IP6 and the side chains of these two lysine residues, we prepared the double mutant K290A, K359A d16-99MACASP1NCSP2, in which the lysine residues were replaced with alanines (Fig. 4a). This double mutant (KAKA) was produced in bacterial cells and purified, and its ability to assemble into VLP was analyzed by FAITH and TEM (Fig. 4b).

TEM analysis showed that the KAKA mutant assembled efficiently into spherical, immature-like particles (Fig. 4c). Interestingly, diameters of KAKA VLPs were similar to wt in the presence of IP6 but about 10% larger than particles of the corresponding wt protein in the absence of IP6 (Fig. 4d). The diameters of KAKA VLPs did not change when assembled in the presence of IP6 (Fig. 4d). FAITH revealed that the efficiency of KAKA mutant assembly was three times higher than that of the wt (Fig. 4e). Moreover, its efficiency was even slightly higher than that of the wt in the presence of IP6 (at a protein hexamer:IP6 ratio of 1:1). The observation that the addition of various concentrations of IP6 did not affect the assembly efficiency of the KAKA mutant (Fig. 4f, salmon columns) strongly supports Dick et al.’s observation (27).

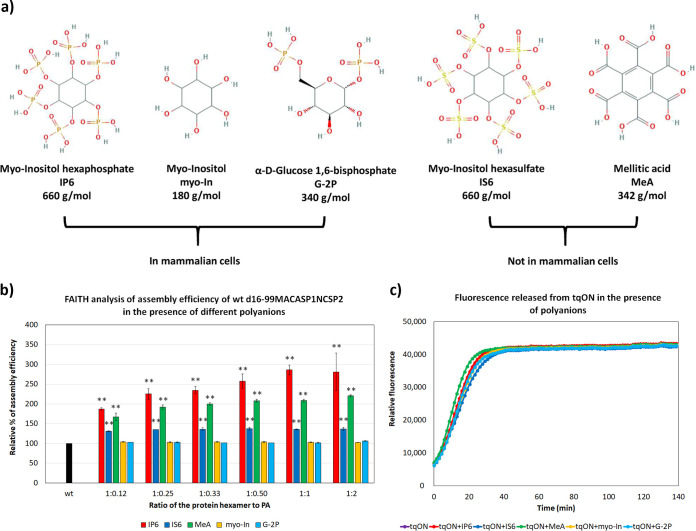

In addition to IP6, we tested other polyanions (PAs) potentially involved in retroviral particle assembly. Based on their similar “geometry” but different charge distributions, we selected hexasulphate (IS6), mellitic acid (MeA), myo-inositol (myo-In), and glucose-1,6-bisphosphate (G-2P) (Fig. 5a). In contrast to myo-In and G-2P, IS6 and MeA are not naturally present in mammalian cells. Similar to IP6, we tested a broad range of CA hexamer:PA ratios (1:0.12 to 1:2). The d16-99MACASP1NCSP2 wt protein, tqON and one of the polyanions were added simultaneously and, following incubation, the assembly efficiency was analyzed by FAITH (Fig. 5b). MeA and IS6 enhanced HIV-1 assembly efficiency 2-fold and 1.5-fold, respectively, while myo-In and G-2P had no significant effect. None of these polyanions had any effect on Exonuclease I activity (Fig. 5c).

FIG 5.

Effect of selected polyanions (PA) on HIV-1 immature particle assembly. (a) Chemical structures of used polyanions: myo-inositol hexaphosphate (IP6), myo-inositol (myo-In), glucose-1,6-bisphosphate (G-2P), myo-inositol hexasulphate (IS6), and mellitic acid (MeA). (b) FAITH analysis of assembly efficiency of HIV-1 d16-99MACASP1NCSP2 wt protein in the presence of IP6 (red), IS6 (royal blue), MeA (green), myo-In (yellow), or G-2P (azure blue) at the indicated protein hexamer:PA ratios. (c) Comparison of fluorescence emission curves demonstrating the kinetics of tqON degradation in the absence of any polyanion (black curve) or in the presence of IP6 (red), IS6 (royal blue), MeA (green), myo-In (yellow), or G-2P (azure blue) at a final concentration of 2.5 μM. P values were assessed by ANOVA using the Tukey-Kramer test (**, P < 0.01).

Quantification of the effect of polyanions on the stability of in vitro preassembled HIV-1 mature-like particles.

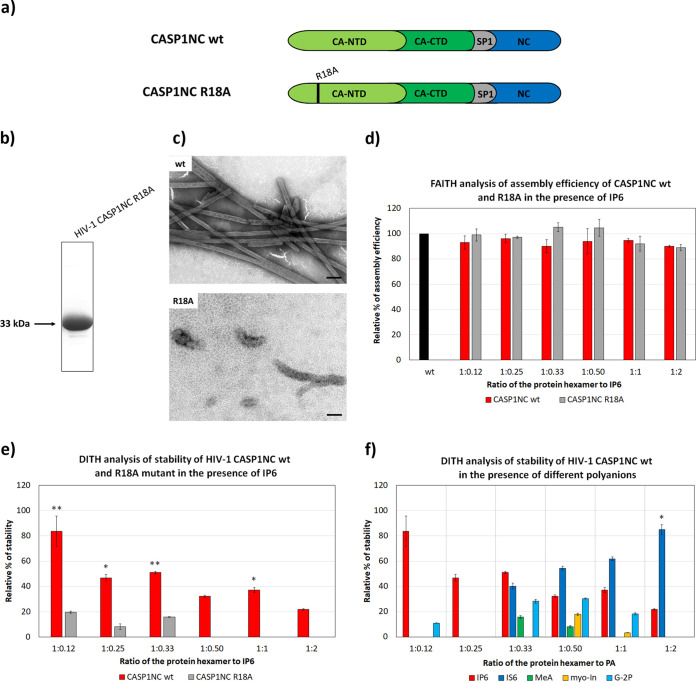

During virus maturation, the immature hexameric lattice formed by Gag polyproteins disintegrates and some of the liberated HIV-1 CA proteins reassemble into an enclosed conical structure, i.e., a mature core. This lattice, composed of CA pentamers and hexamers, protects the HIV-1 genome. In the middle of each hexamer is a pore lined by six arginine residues (R18). The presence of R18 at NTD-CA is crucial for maintaining the stability of the core (24, 28). Moreover, R18 has been identified as a new binding site for IP6, which, during maturation, is released from its binding site in the immature particle. The role of IP6 binding in a mature CA lattice may be to modulate the stability of the viral core (27, 28).

Using a recently established stabilization assay for HIV-1, DITH (33), we sought to verify the role of IP6 as a stabilizer of the HIV-1 core. We prepared HIV-1 CASP1NC wt and R18A mutant proteins (Fig. 6a and b), and used TEM and FAITH to analyze their ability to assemble into tubular mature-like particles (Fig. 6c). TEM showed that, in comparison to wt, the R18A mutant formed more irregular particles. FAITH analysis clearly showed that IP6 did not affect the assembly of either protein (Fig. 6d). DITH analysis was then performed on the preassembled tubular wt and R18A CASP1NC structures. IP6 was added at various concentrations (0.36 to 6 μM) corresponding to protein hexamer:IP6 ratios ranging from 1:0.12 to 1:2, and following a 1-h incubation, the particles were diluted with assembly or disassembly buffers and incubated overnight. The next day, ExoI and Mg2+ were added, and the relative fluorescence released upon tqON degradation was measured (Fig. 6e). The relative percentage of stabilization was then calculated using differences in released fluorescence: (i) the difference between the fluorescence released in the mixture of CASP1NC wt in assembly buffer and disassembly buffer, determined as 0% stability increase (Δ1), and (ii) the difference between the fluorescence released in the mixture of CASP1NC wt or the R18A mutant in disassembly buffer in the presence of IP6 (Δ2). Relative stability was then calculated using the following formula: relative % stability = 100 × Δ2/Δ1 (Fig. 6e and f). While IP6 enhanced the stability of CASP1NC wt mature-like particles across the entire range of concentrations tested (Fig. 6e), the greatest contribution to CASP1NC particle stability was observed at the lowest IP6 concentration.

FIG 6.

Effect of selected polyanions on stability of HIV-1 mature-like particles (a) Schematic representation of HIV-1 CASP1NC wt and R18A mutant. (b) Coomassie brilliant blue-stained SDS polyacrylamide gel of purified HIV-1 CASP1NC R18A. (c) TEM analysis of negatively stained HIV-1 CASP1NC wt and R18A proteins assembled in assembly buffer in the presence of tqON. (d) FAITH: relative assembly efficiency of HIV-1 CASP1NC wt (red columns) and R18A (gray columns) in the presence of different concentrations of IP6, compared to CASP1NC wt or R18A mutant without IP6 (black column). (e) DITH: relative stability of HIV-1 CASP1NC wt and R18A mutant in the presence of increasing concentrations of IP6. The relative stability of wt and R18A CASP1NC in the absence of IP6 in disassembly buffer was considered to be 0%. (f) DITH quantification of relative stability of preassembled HIV-1 CASP1NC wt particles incubated in disassembly buffer in the presence of increasing amounts of IP6 (red), IS6 (royal blue), MeA (green), myo-In (yellow), and G-2P (azure blue) at the indicated PA:protein ratios. P values were assessed by ANOVA using the Tukey-Kramer test (*, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01).

To verify that the R18 residues within the mature hexamer pore structure are involved in IP6 binding, we treated the preassembled wt and R18A CASP1NC particles with IP6, and used DITH to compare their stability. The ability of IP6 to stabilize R18A CASP1NC particles was reduced but not completely abolished (Fig. 6e). This result was surprising, because it suggests that IP6 can bind to another part of mature particles besides R18. Interestingly, when the effect of IP6 was compared with those of the other tested polyanions (Fig. 6f), IS6, a synthetic analog of IP6, showed a strong concentration-dependent stabilization effect. Although the other tested polyanions, particularly G-2P, slightly increased the stability of the mature particles, their contributions were lower than those of IP6 and IS6 (Fig. 6f).

DISCUSSION

Retroviruses use various host cell factors to facilitate critical steps in their replication cycle, including viral particle assembly and uncoating. One of these factors is IP6, which is involved in several steps of the retroviral replication cycle. IP6 contributes significantly to assembly of immature HIV-1 particles, as well as to the maintenance of well-balanced core stability (27, 28). An in vitro study showed that IP6 can compete effectively with both DNA and RNA in binding the MA domain of bovine leukemia virus (BLV) (36). To date, the effects of IP6 on HIV-1 assembly and core stability have been estimated using TEM or by structural approaches. Here, we used quantitative methods to determine the effect of IP6 on the assembly of immature-like HIV-1 particles (FAITH) and the stability of mature-like HIV-1 particles (DITH) in vitro.

Using FAITH, we found that HIV-1 d16-99MACASP1NCSP2 assembled in vitro into VLPs with significantly increased efficacy in the presence of IP6 compared to its absence. This observation is in agreement with the data reported by Dick et al., who found that HIV-1 s-CANC VLPs assembled inefficiently in the absence of IP6, but in the presence of 1 μM IP6, formed particles that were more stable and of uniform spherical shape (27). Our data revealed that the highest assembly efficiency was obtained at a protein hexamer:IP6 molar ratio of 1:1 (final IP6 concentration of 2.5 μM), which corresponds with the idea that one hexamer recruits one molecule of IP6 (27). In addition, we showed that the highest assembly efficiency was achieved when IP6 was present during VLP assembly, while its addition to preassembled particles had a significantly lower effect on assembly efficiency. This is consistent with the proposed mechanism of IP6 incorporation, which assumes that IP6 binds to a site newly formed during the assembly of immature particles. An example of such a site is the six-helix bundle (6HB), which is created during the assembly of the hexameric lattice of HIV-1, Rous sarcoma virus (RSV), or murine leukemia virus (MLV) (14, 27, 37).

During assembly, HIV-1 particles recruit IP6 molecules using two lysine side chains, K290 and K359 (27), which are located in the CA-CTD and 6HB, respectively. Single point mutations of K290 or K359 to alanine (K290A or K359A) reduced Gag assembly efficiency and resulted in the formation of noninfectious particles (38, 39). VLPs assembled from this mutant Gag in cultured cells were of abnormal size and shape, likely due to defective Gag-Gag interactions (38, 40). On the other hand, HIV-1 CA protein carrying the K290A mutation assembled in vitro into long tubules surrounding large clumps (41). These findings led to the hypothesis that this CA K290A aggregation is primarily due to the hydrophobic surface resulting from the replacement of the lysine with alanine (41). We prepared a double mutant (KAKA), in which both lysines responsible for IP6 binding were replaced with alanines (K290A, K359A). Surprisingly, in contrast to the data published for the single K290A mutant, the double mutation significantly enhanced the efficiency of the d16-99MACASP1NCSP2 protein variant to assemble in vitro into VLPs. These particles were of the same spherical shape as those of the wt, but slightly larger. Moreover, the assembly efficiency of the KAKA mutant was 3 times higher than that of the wt, and about 1.2 times higher than that of the wt in the presence of IP6. However, the assembly of the KAKA mutant was not affected by IP6 addition, which supports the crucial role of K290 and K359 residues in IP6 recruitment. It is interesting that reducing the positive charge in the 6HB region (by replacing lysines with alanines) so strongly increased the efficacy of the assembly of VLPs in vitro. As the efficiency of VLP assembly of the KAKA mutant was comparable to that of wt in the presence of IP6, it is tempting to speculate that these lysine residues play an important role in facilitating proper stability of this region during VLP assembly, as well as disassembly upon maturation.

Apart from IP6, mammalian cells contain various other small polyanions that participate in a broad range of processes. Based on molecule size and charge distribution, we selected another four polyanions: myo-inositol (myo-In) and glucose-1,6-bisphosphate (G-2P), which are naturally present in mammalian cells, and inositol hexasulphate (IS6) and mellitic acid (MeA), which are synthetic molecules. Our data showed that, of all these polyanions, HIV-1 preferred IP6 for the assembly of immature-like particles. These results are consistent with previous studies that tested the effect of mellitic acid and inositol phosphates containing fewer phosphate groups (27, 29).

The hallmarks of HIV-1 maturation are substantial conformational changes resulting in the formation of a mature, fully infectious virus. Among these changes, those connected to the removal of the 6HB from the C-terminal portion of CA cause displacement of the IP6-binding site. The newly formed mature lattice is composed of capsid hexamers and pentamers. In the center of each hexamer, helix 1 and the β-hairpin together form an extended dynamic pore through the hexamer, which is lined with six arginine residues (R18) (24). It is assumed that IP6 binds to this R18 pore, thus stabilizing the mature hexameric lattice (27, 28). As arginine residues within the β-hairpin have been reported in retroviral species other than HIV-1 (41–43), it is likely that other retroviruses also can bind IP6 or other polyanions. In the MLV cryo-EM structure, a faint additional density, likely representing a negatively charged ion, was reported within the central pore of the mature CA-NTD hexamer structure (37). Using our stabilization assay for HIV-1 (DITH), we quantified the effect of IP6 and other polyanions on the stability of mature-like HIV-1 particles (33). In vitro-assembled mature-like tubular particles were prepared from CASP1NC and a short oligonucleotide, tqON. To verify that R18 is responsible for the interaction with IP6, we also prepared a R18A CASP1NC mutant. In comparison to the wt, R18A CASP1NC particles were not uniformly tubular. This is in agreement with previous studies (27, 41), which showed that R18A mutant particles adopted various shapes, such as cylinders, cones, and spheres, of various sizes. This phenotype can occur due to the ability of the R18A mutant to incorporate more pentamers into the hexameric lattice (41). FAITH analysis clearly showed that the addition of IP6 did not affect the assembly of wt or R18A CASP1NC. As expected, DITH confirmed that IP6 had considerably less effect on the stability of tubular R18A CASP1NC particles than on their wt equivalent. These results correlate well with those reported by Dick et al. and Mallery et al. (27, 28). DITH analysis showed that IS6 could also stabilize the mature-like HIV-1 lattice, and, interestingly, that it stabilized the particles at higher concentrations than IP6 did. This points to a certain specificity for molecules that can bind to the R18 pore.

In conclusion, the combination of FAITH and DITH enabled us to quantify the contribution of IP6 to the assembly efficiency of immature-like HIV-1 particles or the stability of the mature-like particles. Using FAITH, we showed that the highest assembly efficiency was achieved in the presence of IP6 in a concentration corresponding to a protein hexamer:IP6 molar ratio of 1:1. We also confirmed that K290 and K359 are critical for the beneficial effect of IP6 on increasing VLP assembly efficiency. In addition to IP6, other small polyanions also enhanced HIV-1 particle assembly, albeit with lower efficiency. Using DITH, we quantified the effect of a series of small polyanions, including IP6, on the stabilization of wt and R18A mutant mature-like HIV-1 particles. This analysis showed that both IP6 and IS6 stabilized the particles in a concentration-dependent manner. In addition, we provided evidence that a mutation of residue R18, thought to be responsible for IP6 binding in the mature lattice, decreased the stabilization effect of IP6.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Construct preparations.

HIV-1 CASP1NC, encoding CA, SP1 and NC fusion protein, was prepared as described earlier (32, 34). A point mutation R18A was prepared by EMILI mutagenesis (44), using the following primers: 5′ CANC HIV R18A CCA TAT CAC CTG CAA CTT TAA ATG CAT GGG; 3′ CANC HIV R18A GCA TTT AAA GTT GCA GGT GAT ATG GCC TGA TGT ACC. d16-99MACASP1NCSP2, encoding the deletion of 16 to 99 amino acids within MA, was constructed by inserting the ClaI-XhoI PCR fragment obtained from the pSAX2 vector into the HIV-1 Δp6Gag pET expression vector. A double point mutation K290, K359A was prepared by mutagenesis (45), using the primers: 5′ K290A GGA CCA GCG GAA CCC TTT AG; 3′ K290A GTT CCG CTG GTC CTT GTC TTA TG; 5′ K359A CGG CCA TGC GGC AAG AGT TTT GGC TG; and 3′ K359A CTC TTG CCG CAT GGC CGG GTC CTC C. Newly created vectors were verified by sequencing.

Protein expression and purification.

The HIV-1 CASP1NC, d16-99MACASP1NCSP2, and their mutant proteins were purified as previously described (32, 34, 46) with some modifications. The proteins were expressed in E. coli BL21(DE3) cells. The bacterial pellet containing HIV-1 CASP1NC wt or mutant obtained from 2.4 liters of LB medium was resuspended in 100 ml of buffer D1 (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8, 0.5 M NaCl, 10% glycerol, 1 mM EDTA, 10 mM DTT, 1 mM Triton X-100, 1× health protease inhibitor cocktail), disrupted with 10 mg lysozyme (Merck) and sonicated (4 × 45 s, total energy 6 kJ) on ice. Polyethyleneimine was added to the cell lysate to a final concentration of 0.3% (wt/vol), and cell debris and nucleic acids were removed by centrifugation (Beckman, 30,000 rcf, 30 min, 4°C). The HIV-1 CASP1NC protein was diluted to a final NaCl concentration of 100 mM with buffer D2 (20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 10 μM ZnCl2, 10 mM DTT), filtered through a 0.45-μm pore filter (Amicon), and loaded onto a HiPrepSP FF 16/10 column (GE Healthcare) equilibrated in buffer D2. The bound proteins were eluted with NaCl gradient from 0 M to 1 M NaCl in buffer D2. The bacterial pellet containing HIV-1 d16-99MACASP1NCSP2 wt or mutant obtained from 2.4 liters of LB medium was resuspended in 100 ml of buffer E1 (20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8, 0.5 M NaCl, 10% glycerol, 1 mM EDTA, 10 mM DTT, 1 mM Triton X-100, 1× health protease inhibitor cocktail). The cells were then disrupted and treated by polyethylenimine as described above. After centrifugation, clear supernatant was precipitated with ammonium sulfate (70% saturation) and centrifuged (Beckman, 30,000 rcf, 60 min, 4°C). The pellet was resuspended in 50 ml of buffer E2 (20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 0.1 M NaCl, 10 μM ZnCl2, 10 mM DTT) and dialyzed against the same buffer. The HIV-1 d16-99MACASP1NCSP2 protein was filtered through a 0.45-μm pore filter (Amicon) and loaded onto a HiPrepSP FF 16/10 column (GE Healthcare) equilibrated in buffer E2. The bound proteins were eluted with a NaCl gradient from 0.1 M to 1 M NaCl in buffer E2.The fractions containing desired protein were pooled and concentrated to an approximate volume of 5 ml using an AmiconUltra-4 filter. The sample was then loaded onto a HiLoad26/600 Superdex 200 pg (GE Healthcare) column equilibrated in buffer D4 (20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 0.5 M NaCl, 10 μM ZnCl2, 10 mM DTT). The protein from pooled fractions was concentrated to 3.3 mg/ml and stored at –80°C. The purity of the proteins was analyzed by SDS-PAGE and verified by Western blotting using anti-HIV CA antibodies produced in-house (47).

Fast Assembly Inhibitor Test for HIV: FAITH.

To test and quantify the effect of polyanions on HIV-1 assembly, we used FAITH (32). We selected five different polyanions: inositol hexaphosphate (IP6), inositol hexasulphate (IS6), mellitic acid (MeA), myo-inositol (myo-In), and glucose-1,6-bisphosphate (G-2P). Aliquots of 60 μg of HIV-1 CASP1NC (18 μM) or d16-99MACASP1NCSP2 (15 μM), purified as described above, was mixed with 3 μg of dually labeled oligonucleotide (tqON) and selected polyanions (PAs) in assembly buffer (50 mM Tris pH 8.0, 1 μM ZnCl2, 340 mM NaCl) in a 96-well plate at room temperature. Polyanion concentrations ranged from 0.3 to 5 μM for d16-99MACASP1NCSP2 and 0.4 to 6 μM for CASP1NC, corresponding to the protein hexamer:PA ratios from 1:0.12 to 1:2. After 3 h of incubation, exonuclease I (ExoI) together with Mg2+ ions were added to the mixture and fluorescence of the fluorophore released from degraded tqON present in the solution was measured using the plate reader Tecan M200Pro. Assembly efficiency was calculated from the formula E = 100 × ΔF2/ΔF1, in which ΔF1 corresponded to the difference between relative fluorescence of tqON and relative fluorescence of tqON in the presence of d16-99MACASP1NCSP2 or CASP1NC, and ΔF2 corresponded to the difference between relative fluorescence of tqON and relative fluorescence of tqON in the presence of d16-99MACASP1NCSP2 or CASP1NC and polyanions. The fluorescence was recorded for 40 min for d16-99MACASP1NCSP2 assembly and 35 min for CASP1NC assembly.

Disassembly Inhibitory Test for HIV: DITH.

DITH was used to determine the stabilizing effect of polyanions during disassembly of in vitro preassembled HIV-1 CASP1NC tubular structures. The polyanions were added to the preassembled particles and the mixture was incubated 1 h at room temperature. Next, 100 μl of assembly buffer (50 mM Tris pH 7.0, 1 μM ZnCl2, 340 mM NaCl) or disassembly buffer (50 mM Tris pH 7.0, 1 μM ZnCl2) was added to each sample in a 96-well plate and incubation under moderate agitation (480 rpm) was continued overnight at room temperature. Then, ExoI and Mg2+ ions were added and fluorescence was measured using the plate reader Tecan M200Pro. Relative % of stability was calculated using the formula: relative % of stability = 100 × Δ2/Δ1. Value Δ1 represents the difference of relative fluorescence of CASP1NC in assembly and disassembly buffer measured at 90 min. Value Δ2 represents the difference between the relative fluorescence of tqON at 90 min in a disassembly reaction of CASP1NC in the presence of IP6 and disassembly reaction of CANC in the absence of IP6. The stability of wt was set as 0% of stability increase.

Transmission electron microscopy.

Particles formed during the in vitro assembly reaction and disassembled during disassembly were visualized by negative staining. Particles were deposited on a carbon-coated copper grid for 2 to 5 min. The grid with sample was dried, than washed twice with deionized water and negatively stained with 4% sodium silico tungstate (pH 7.4) or, alternatively, with 1% uranyl acetate for 30 s. The samples were visualized using a JEOL JEM-1010 transmission electron microscope (Jeol, Japan) at 80 kV. Images were recorded with an AnalySIS MegaView III CCD camera.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This research was funded by GA ČR(CZ) GA20-19906S.

We thank Hillary Hoffman and Craig Riddell for language correction.

REFERENCES

- 1.Briggs JA, Riches JD, Glass B, Bartonova V, Zanetti G, Krausslich HG. 2009. Structure and assembly of immature HIV. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 106:11090–11095. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0903535106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jouvenet N, Simon SM, Bieniasz PD. 2009. Imaging the interaction of HIV-1 genomes and Gag during assembly of individual viral particles. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 106:19114–19119. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0907364106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kutluay SB, Bieniasz PD. 2010. Analysis of the initiating events in HIV-1 particle assembly and genome packaging. PLoS Pathog 6:e1001200. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1001200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bryant M, Ratner L. 1990. Myristoylation-dependent replication and assembly of human immunodeficiency virus 1. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 87:523–527. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.2.523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhou W, Parent LJ, Wills JW, Resh MD. 1994. Identification of a membrane-binding domain within the amino-terminal region of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Gag protein which interacts with acidic phospholipids. J Virol 68:2556–2569. doi: 10.1128/JVI.68.4.2556-2569.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Saad JS, Miller J, Tai J, Kim A, Ghanam RH, Summers MF. 2006. Structural basis for targeting HIV-1 Gag proteins to the plasma membrane for virus assembly. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 103:11364–11369. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0602818103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ono A, Ablan SD, Lockett SJ, Nagashima K, Freed EO. 2004. Phosphatidylinositol (4,5) bisphosphate regulates HIV-1 Gag targeting to the plasma membrane. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 101:14889–14894. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0405596101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Briggs JA, Simon MN, Gross I, Krausslich HG, Fuller SD, Vogt VM, Johnson MC. 2004. The stoichiometry of Gag protein in HIV-1. Nat Struct Mol Biol 11:672–675. doi: 10.1038/nsmb785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Li S, Hill CP, Sundquist WI, Finch JT. 2000. Image reconstructions of helical assemblies of the HIV-1 CA protein. Nature 407:409–413. doi: 10.1038/35030177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pornillos O, Ganser-Pornillos BK, Yeager M. 2011. Atomic-level modelling of the HIV capsid. Nature 469:424–427. doi: 10.1038/nature09640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mattei S, Glass B, Hagen WJ, Krausslich HG, Briggs JA. 2016. The structure and flexibility of conical HIV-1 capsids determined within intact virions. Science 354:1434–1437. doi: 10.1126/science.aah4972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ganser BK, Li S, Klishko VY, Finch JT, Sundquist WI. 1999. Assembly and analysis of conical models for the HIV-1 core. Science 283:80–83. doi: 10.1126/science.283.5398.80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Borsetti A, Ohagen A, Gottlinger HG. 1998. The C-terminal half of the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Gag precursor is sufficient for efficient particle assembly. J Virol 72:9313–9317. doi: 10.1128/JVI.72.11.9313-9317.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schur FK, Hagen WJ, Rumlova M, Ruml T, Muller B, Krausslich HG, Briggs JA. 2015. Structure of the immature HIV-1 capsid in intact virus particles at 8.8 A resolution. Nature 517:505–508. doi: 10.1038/nature13838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mammano F, Ohagen A, Hoglund S, Gottlinger HG. 1994. Role of the major homology region of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 in virion morphogenesis. J Virol 68:4927–4936. doi: 10.1128/JVI.68.8.4927-4936.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gross I, Hohenberg H, Wilk T, Wiegers K, Grattinger M, Muller B, Fuller S, Krausslich HG. 2000. A conformational switch controlling HIV-1 morphogenesis. EMBO J 19:103–113. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.1.103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schur FK, Obr M, Hagen WJ, Wan W, Jakobi AJ, Kirkpatrick JM, Sachse C, Krausslich HG, Briggs JA. 2016. An atomic model of HIV-1 capsid-SP1 reveals structures regulating assembly and maturation. Science 353:506–508. doi: 10.1126/science.aaf9620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wagner JM, Zadrozny KK, Chrustowicz J, Purdy MD, Yeager M, Ganser-Pornillos BK, Pornillos O. 2016. Crystal structure of an HIV assembly and maturation switch. Elife 5:e17063. doi: 10.7554/eLife.17063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wright ER, Schooler JB, Ding HJ, Kieffer C, Fillmore C, Sundquist WI, Jensen GJ. 2007. Electron cryotomography of immature HIV-1 virions reveals the structure of the CA and SP1 Gag shells. EMBO J 26:2218–2226. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhao G, Perilla JR, Yufenyuy EL, Meng X, Chen B, Ning J, Ahn J, Gronenborn AM, Schulten K, Aiken C, Zhang P. 2013. Mature HIV-1 capsid structure by cryo-electron microscopy and all-atom molecular dynamics. Nature 497:643–646. doi: 10.1038/nature12162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gres AT, Kirby KA, KewalRamani VN, Tanner JJ, Pornillos O, Sarafianos SG. 2015. STRUCTURAL VIROLOGY. X-ray crystal structures of native HIV-1 capsid protein reveal conformational variability. Science 349:99–103. doi: 10.1126/science.aaa5936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ganser-Pornillos BK, Cheng A, Yeager M. 2007. Structure of full-length HIV-1 CA: a model for the mature capsid lattice. Cell 131:70–79. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.08.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Byeon IJ, Meng X, Jung J, Zhao G, Yang R, Ahn J, Shi J, Concel J, Aiken C, Zhang P, Gronenborn AM. 2009. Structural convergence between Cryo-EM and NMR reveals intersubunit interactions critical for HIV-1 capsid function. Cell 139:780–790. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.10.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jacques DA, McEwan WA, Hilditch L, Price AJ, Towers GJ, James LC. 2016. HIV-1 uses dynamic capsid pores to import nucleotides and fuel encapsidated DNA synthesis. Nature 536:349–353. doi: 10.1038/nature19098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bhattacharya A, Alam SL, Fricke T, Zadrozny K, Sedzicki J, Taylor AB, Demeler B, Pornillos O, Ganser-Pornillos BK, Diaz-Griffero F, Ivanov DN, Yeager M. 2014. Structural basis of HIV-1 capsid recognition by PF74 and CPSF6. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 111:18625–18630. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1419945112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Price AJ, Jacques DA, McEwan WA, Fletcher AJ, Essig S, Chin JW, Halambage UD, Aiken C, James LC. 2014. Host cofactors and pharmacologic ligands share an essential interface in HIV-1 capsid that is lost upon disassembly. PLoS Pathog 10:e1004459. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dick RA, Zadrozny KK, Xu C, Schur FKM, Lyddon TD, Ricana CL, Wagner JM, Perilla JR, Ganser-Pornillos BK, Johnson MC, Pornillos O, Vogt VM. 2018. Inositol phosphates are assembly co-factors for HIV-1. Nature 560:509–512. doi: 10.1038/s41586-018-0396-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mallery DL, Marquez CL, McEwan WA, Dickson CF, Jacques DA, Anandapadamanaban M, Bichel K, Towers GJ, Saiardi A, Bocking T, James LC. 2018. IP6 is an HIV pocket factor that prevents capsid collapse and promotes DNA synthesis. Elife 7:e35335. doi: 10.7554/eLife.35335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Campbell S, Fisher RJ, Towler EM, Fox S, Issaq HJ, Wolfe T, Phillips LR, Rein A. 2001. Modulation of HIV-like particle assembly in vitro by inositol phosphates. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 98:10875–10879. doi: 10.1073/pnas.191224698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Datta SA, Zhao Z, Clark PK, Tarasov S, Alexandratos JN, Campbell SJ, Kvaratskhelia M, Lebowitz J, Rein A. 2007. Interactions between HIV-1 Gag molecules in solution: an inositol phosphate-mediated switch. J Mol Biol 365:799–811. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.10.072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mallery DL, Faysal KMR, Kleinpeter A, Wilson MSC, Vaysburd M, Fletcher AJ, Novikova M, Bocking T, Freed EO, Saiardi A, James LC. 2019. Cellular IP6 levels limit HIV production while viruses that cannot efficiently package IP6 are attenuated for infection and replication. Cell Rep 29:3983–3996.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2019.11.050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hadravova R, Rumlova M, Ruml T. 2015. FAITH—Fast Assembly Inhibitor Test for HIV. Virology 486:78–87. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2015.08.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dostálková A, Hadravová R, Kaufman F, Křížová I, Škach K, Flegel M, Hrabal R, Ruml T, Rumlová M. 2019. A simple, high-throughput stabilization assay to test HIV-1 uncoating inhibitors. Sci Rep 9:17076. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-53483-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ulbrich P, Haubova S, Nermut MV, Hunter E, Rumlova M, Ruml T. 2006. Distinct roles for nucleic acid in in vitro assembly of purified Mason-Pfizer monkey virus CANC proteins. J Virol 80:7089–7099. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02694-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gross I, Hohenberg H, Huckhagel C, Kräusslich HG. 1998. N-Terminal extension of human immunodeficiency virus capsid protein converts the in vitro assembly phenotype from tubular to spherical particles. J Virol 72:4798–4810. doi: 10.1128/JVI.72.6.4798-4810.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Qualley DF, Lackey CM, Paterson JP. 2013. Inositol phosphates compete with nucleic acids for binding to bovine leukemia virus matrix protein: implications for deltaretroviral assembly. Proteins 81:1377–1385. doi: 10.1002/prot.24281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Qu K, Glass B, Dolezal M, Schur FKM, Murciano B, Rein A, Rumlova M, Ruml T, Krausslich HG, Briggs JAG. 2018. Structure and architecture of immature and mature murine leukemia virus capsids. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 115:E11751–E11760. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1811580115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.von Schwedler UK, Stray KM, Garrus JE, Sundquist WI. 2003. Functional surfaces of the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 capsid protein. J Virol 77:5439–5450. doi: 10.1128/jvi.77.9.5439-5450.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Melamed D, Mark-Danieli M, Kenan-Eichler M, Kraus O, Castiel A, Laham N, Pupko T, Glaser F, Ben-Tal N, Bacharach E. 2004. The conserved carboxy terminus of the capsid domain of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 gag protein is important for virion assembly and release. J Virol 78:9675–9688. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.18.9675-9688.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chang YF, Wang SM, Huang KJ, Wang CT. 2007. Mutations in capsid major homology region affect assembly and membrane affinity of HIV-1 Gag. J Mol Biol 370:585–597. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.05.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ganser-Pornillos BK, von Schwedler UK, Stray KM, Aiken C, Sundquist WI. 2004. Assembly properties of the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 CA protein. J Virol 78:2545–2552. doi: 10.1128/jvi.78.5.2545-2552.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Obr M, Hadravová R, DoleŽal M, KříŽová I, Papoušková V, Zídek L, Hrabal R, Ruml T, Rumlová M. 2014. Stabilization of the beta-hairpin in Mason-Pfizer monkey virus capsid protein—a critical step for infectivity. Retrovirology 11:94. doi: 10.1186/s12977-014-0094-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chen K, Piszczek G, Carter C, Tjandra N. 2013. The maturational refolding of the β-hairpin motif of equine infectious anemia virus capsid protein extends its helix α1 at capsid assembly locus. J Biol Chem 288:1511–1520. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.425140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fuzik T, Ulbrich P, Ruml T. 2014. Efficient Mutagenesis Independent of Ligation (EMILI). J Microbiol Methods 106:67–71. doi: 10.1016/j.mimet.2014.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Křížová I, Hadravová R, Štokrová J, Günterová J, Doležal M, Ruml T, Rumlová M, Pichová I. 2012. The G-patch domain of Mason-Pfizer monkey virus is a part of reverse transcriptase. J Virol 86:1988–1998. doi: 10.1128/JVI.06638-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Campbell S, Vogt VM. 1995. Self-assembly in vitro of purified Ca-Nc proteins from Rous sarcoma virus and human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J Virol 69:6487–6497. doi: 10.1128/JVI.69.10.6487-6497.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rumlová M, Křížová I, Zelenka J, Weber J, Ruml T. 2018. Does BCA3 play a role in the HIV-1 replication cycle? Viruses 10:212. doi: 10.3390/v10040212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]