Abstract

Introduction

Diabetes medications can substantially lower blood sugar, thereby improving health outcomes. Despite substantial efforts targeting this issue, diabetes medication adherence remains suboptimal. We present the development and implementation of an intervention emphasizing peer modeling and support as strategies to improve medication adherence.

Methods

Program adaptation, pretesting, and peer coach training were combined in an iterative process with community stakeholders. Peer coaches were community residents who had diabetes or took care of family members with diabetes. Study participants were community-dwelling adults taking diabetes oral medications who reported medication non-adherence or wanted help taking their medications.

Results

The resulting intervention consisted of a six-month, 11-session telephone-delivered program. Nineteen peer coaches were trained and certified to deliver the intervention. The 473 study participants were mostly African-Americans (91%), women (79%), and low-income (70% reporting annual income <$20,000). Of the 203 intervention participants, 85% completed the program, with 82% completing all program sessions. Ninety-five percent reported high program satisfaction, and 91% found the program materials helpful, 96% found the videos helpful, 93% felt their peer was easy to talk with, and 95% reported that support from their peer was great or good. Moreover, 93% reported peers knew the program well, and 93% would recommend a peer to a relative with a similar health condition.

Discussion

This intervention was developed and implemented in underserved communities with high retention and fidelity. Participants expressed high satisfaction with the program. Our approach may be helpful for others seeking to develop a medication adherence program in their communities.

Keywords: Diabetes, Adherence, Underserved, Community-based, African American, Southern, Social cognitive theory

1. Introduction

Improving adherence to diabetes medications continues to be a challenging public health issue [1,2]. A 2015 review found adherence rates have remained unchanged since 2007 despite substantial additions to the literature targeting this issue [3,4]. The economic impact of non-adherence to medications is significant, resulting in higher disease-related medical costs and healthcare utilization [[5], [6], [7]]. For patients with diabetes, non-adherence to medications has been associated with worse glycemic control and clinical outcomes [6,[8], [9], [10]]. While studies show that working with patients and providers to develop appropriate medication regimens can improve diabetes outcomes and reduce risk for complications, interventions to date have shown modest effects on adherence [11]. In this paper, we describe the stake-holder engaged approach we used to develop a peer-support intervention to improve medication adherence for individuals with diabetes, as well as the satisfaction intervention participants reported after engaging in the intervention.

Achieving lasting change in any health behavior is difficult, and medication adherence is no exception. Because it is influenced by a complex array of factors operating at multiple levels, including patient, provider, and system levels [12], interventions must identify the most relevant factors for patients and provide strategies tailored to address them. The literature shows that tailored programs are more effective in increasing adherence to medications [[13], [14], [15]]. In addition, patients can be nonadherent in different ways, whether it be intentional (i.e., when the patient makes an active choice, influenced by beliefs and motivations related to diabetes and its treatment, not to follow the prescribed treatment) and/or unintentional (i.e., forgetting, misunderstanding the instructions, or difficulties with administration, such as having trouble opening the medicine bottle). Thus, interventions should contain multiple strategies (i.e., educational, behavioral, affective) that addresses different types of nonadherence, with the goal of initiating and sustaining good adherence.

With the objective of providing a multifaceted, tailored intervention, we developed and implemented Living Well with Diabetes. Living Well was developed guided by social cognitive theory and the lived experience of illness described in the chronic illness trajectory framework [[16], [17], [18], [19]]. Storytelling by community members and discussions with peer coaches were used to help participants come to terms with their illness and relate medication adherence and other self-care behaviors to maintaining or rebuilding their sense of identity and personal narrative.

Illness trajectory framework calls for assisting patients with balancing their illness-related tasks against those of everyday life. We developed a program telephonic peer support to provide a flexible and individualized approach. Peer coaches were uniquely positioned to deliver the intervention. Due to their personal experience with diabetes, either living with diabetes themselves or closely caring for family with diabetes, and residing in similar communities, peers provided emotional support while helping participants develop realistic illness management strategies. Storytelling has been used effectively as a strategy to help individuals cope with their illnesses, promote health behaviors in underserved communities, and decrease social isolation [[20], [21], [22]]. Storytelling videos encourage homophily, reassuring patients that others like them have faced and overcome similar self-care barriers. Therefore, we used peer coaches and storytelling to provide education and behavioral strategies to improve medication adherence and other self-care behaviors in individuals living with diabetes. While a future paper will report the results of the trial evaluating the efficacy of the intervention program, we describe in this paper the development, implementation, and process evaluation results of the Living Well with Diabetes intervention.

2. Methods

2.1. Study setting

The Living Well with Diabetes intervention was developed in a rural region known as the Alabama Black Belt. This region has geopolitical and historical significance in that it is part of what is known as the southern Black Belt, an area stretching from Texas to Maryland [23]. The label of “Black Belt” reflects both the physical and demographic characteristics of the region; believed to originate from the rich, dark soil that characterizes this region of Alabama [24]. Today, this area is populated by large numbers of African Americans; according to the U.S. Census Bureau's 2018 estimates, in 11 of the 17 Alabama counties traditionally included in the region [23], African Americans comprise 50% or more of the population [25]. It is a region that includes the poorest counties in the US, heavily burdened by chronic diseases like diabetes, with the prevalence of diabetes double national averages, and very scarce availability of medical resources [26]. Age-adjusted mortality rates in this region are 20% higher than for average Americans, and 39% higher for African Americans in the region than for average Americans [27]. Our group has been working in partnership with residents of the Alabama Black Belt for over 10 years, conducting community-partnered trials of peer coaching interventions designed to improve quality of life and cardiovascular risk factors for area residents.

The Living Well with Diabetes intervention was evaluated in a cluster randomized controlled trial conducted between 2014 and 2018 in rural communities located in the Alabama Black Belt and in underserved neighborhoods in the Birmingham area. The main study hypotheses tested were that intervention participants would have higher medication adherence and significantly greater improvement in A1c, BP, LDL-C, and measures of quality of life, and self-efficacy compared to control participants. The clusters were towns and neighborhoods, blocked on small (<1000 residents), medium (1000–1999 residents), and large (≥2000 residents). Intervention participants received the Living Well with Diabetes program, a six-month 11-session diabetes self-management program delivered by peer coaches. Control participants received a self-paced general health education program without peer coaches which is described below. The study was designed to be able to detect clinically important changes in A1c of 0.4%, resulting in a targeted sample size of 500, allowing for 20% attrition.

2.2. General health education program description

The self-paced general health education program consisted of eight videos of 10–20 min duration that covered topics unrelated to the study outcomes: dementia and Alzheimer's disease, breast cancer, colorectal cancer, osteoporosis and fall prevention, oral health, eye health, foot care, and driving safety. Participants received a DVD with the videos at study enrollment. Participants received brief telephone calls from study staff at months 1, 3, and 5 to ensure participants were able to access the videos on the DVD and to answer questions.

2.3. Living Well with diabetes intervention development and adaptation

The Living Well with Diabetes intervention structure and content was adapted from two diabetes self-management programs delivered by peer coaches previously developed by our group [[28], [29], [30]]. The original programs were based on social cognitive theory [19] and focused on diabetes basics, healthy eating, physical activity, getting support from family and friends, and having productive interactions with health care providers. Intervention participants viewed a video that delivered educational content, followed by a structured telephone session during which they reviewed the content with their peer coach and set individualized self-management goals and plans for how to achieve them. Participant then carried out their plans, monitored their progress, and watched the video for their next coaching session. The Living Well with Diabetes program built on these elements to create a medication adherence intervention, using the Chronic Illness Trajectory model as the guiding framework [16,17] to develop new educational content and storytelling videos.

2.3.1. Phase 1: formative work

The goal of this phase was to identify themes and craft messages for storytelling videos and to develop diabetes self-care and medication education that incorporated these themes and was culturally appropriate for our participant population. The study team conducted focus groups, nominal group sessions, and semi-structured interviews with community members representing the patient population and with peer coaches that had prior experience working with diabetes patients. We present the key findings related to program development below.

First, focus groups and semi-structured interviews were conducted with community members who had been diagnosed with diabetes and were taking oral medications for their diabetes. Individuals who reported that they were not adherent to their medications or wanted help with taking their medications were included.

The focus group moderator guide was developed using concepts from the Chronic Illness Trajectory Framework and focused on three areas: participants' understanding of diabetes and diabetes complications, impact of diabetes on participants' lives, and strategies to live well with diabetes. Semi-structured interviews explored the participant's transition from the initial diagnosis of diabetes to their current experience of living with diabetes. This was done because many people find the initial diagnosis of diabetes emotionally stressful and often experience a period of denial. A major goal of the intervention was to help individuals move past denial to acceptance and recognition and commitment to self-care, including medication adherence. Findings were used to identify themes for inclusion in the storytelling videos that would provide peers modeling their own transitions to a stable state during which they recognized the importance of medications and adherence in order to live full lives despite having a serious chronic illness. Table 1 presents a summary of these themes.

Table 1.

Summary of themes emerging from focus groups and interviews for storytelling videos.

| Positive messages that focus on living well and daily quality of life rather than disease management Emotional experience of being diagnosed with diabetes Challenges encountered in integrating self-management tasks into daily routine Future goals/motivation to do the work of self-management Reasons why the decision was made to change diet/start exercising/take medications Concrete strategies other people with diabetes use to make and sustain behavior changes Emphasis on how taking care of one's diabetes can help improve the health of the entire family Ways to access resources in the community |

Finally, nominal group sessions were conducted to identify and then prioritize common questions from participants regarding diabetes self-management and diabetes medications. These groups were conducted because our past experience with peer coaching interventions revealed that community members grew close to their peer coaches and often asked questions about their disease and medications unrelated to medication adherence. A major goal of the nominal groups was to better understand community member priorities in order to integrate content that was important to participants in addition to medication adherence.

2.3.2. Phase 2: video development, integrating themes into the intervention

The study team used the themes identified in the qualitative work to develop a draft of the intervention materials, which consisted of session videos, the peer coach manual, and a participant activity book. First, new topics and patient priorities identified during the qualitative work were used to modify the existing education content. For example, participants expressed a need for concrete strategies for self-care that fit their daily realities, such as having to grocery shop at dollar stores or convenience stores. For this specific example, the team worked with a dietitian to develop a video that provided strategies for choosing healthier foods when shopping at a convenience store and then creating healthy dishes around those foods. Second, the study team used themes identified in the nominal group sessions to organize the educational content. For example, participant desire to manage diabetes through diet and exercise and their ambivalence toward medications required the study team to create program sessions that were responsive to participant priorities while encouraging medication adherence. Although every session called for setting a medication adherence plan, the program did not focus solely on medication adherence; rather, the program provided information and strategies on healthy eating and physical activity as well as medication adherence, and these sessions were conducted early in the program schedule. In addition, each session was structured so that it not only provided information and strategies on each self-management activity but linked the activity to living meaningfully now and into the future. Thus, themes that arose during the qualitative phase informed the addition of new topics and organization of sessions.

Finally, the study team used the themes identified during the qualitative phase to develop prompts to be used during storytelling recording sessions. Two types of videos were recorded. Short interviews (in the format of “man on the street” interviews) were conducted with people at a local park and at different community events, with the goal of capturing a wide variety of strategies used to take medications, exercise, and eat healthy. Longer stories that addressed more complex themes were recorded in one-on-one interviews. These story clips were integrated into the educational information in the session videos. These clips also provided starting points for discussions between peer coaches and participants during the telephone sessions.

2.3.3. Phase 3: refining materials, peer coach training

Refinement of program materials combined peer coach training and intervention pretesting, developed in a prior study and described in detail elsewhere [28]. Training began with two in-person sessions that covered basic skills like goal setting, motivational interviewing, and effective communication skills. This was followed by three months of session-specific training during which peer coaches were paired together to practice the sessions through role-play, playing the part of the peer coach and playing the client at least once, but more often if the peer coach felt the need for more practice. When a peer coach felt confident enough for certification, study staff assessed the following: 1) understanding of educational content and themes for each session; 2) session fidelity; 3) relationship/rapport-building with participant; and 4) other miscellaneous observations or concerns regarding the peer coach, if any. If a peer coach did not pass certification initially, study staff offered additional practice until the peer coach was ready to try again. All peer coaches were certified separately on each of the six intensive intervention sessions and the maintenance sessions (see below).

In addition to assessing peer coach skills, study staff used certification sessions to solicit suggestions for refining program materials and incorporated many of these suggestion into the intervention and data collection protocols. This serves as an effective engagement strategy, since coaches noted their suggestions being incorporated, enhancing their feeling of ownership of the program. In our past work, this strategy has led to high fidelity of program implementation. Table 2 provides a summary of the changes made to the intervention based on the feedback from the peer coach training and intervention pretesting process.

Table 2.

Changes made to the intervention based on the feedback from the peer coach training and intervention pretest process.

| Client plan book |

|

|---|---|

| Participant activity book |

|

| Peer coach manual |

|

| Program videos |

|

| Peer coach training |

|

Final Living Well with Diabetes intervention.

The final Living Well with Diabetes intervention consisted of 11 total sessions. The program began with 6 weekly sessions of average duration 30–45 min, which constituted the intensive intervention phase. This was followed by 2 transition sessions 2 weeks apart, followed by 3 monthly maintenance sessions for a total of 6 months. Transition sessions were on average 30–45 min long, and maintenance sessions were on average 15 min long. The weekly sessions were supported by videos with educational content and storytelling by community members on accepting their illness and overcoming barriers to medication taking and other self-care activities. Participants received an activity book, a DVD player which was theirs to keep, and a program DVD. If individuals wanted to participate but did not have reliable access to a telephone with enough minutes for the intervention sessions, the program provided them a cell phone to use for the duration of the intervention. Prior to the 6 weekly sessions with the peer coach, the participant watched a 15–30 min video that provided that session's educational content. The telephone session with the peer coach reinforced the video's messages through interactive activities. Table 3 provides a summary of content included in the final intervention.

Table 3.

Content of the Living Well with Diabetes intervention.

| Session | Video Title | Session Content | Goals/Homework |

|---|---|---|---|

| Introduction to Living Well with Diabetes | Introduction to the Living Well with Diabetes Program and Diabetes Basics |

|

|

| Healthy eating | Health Eating |

|

|

| Physical activity and your health | Adding physical activity to your daily life |

|

|

| Diabetes medications | Diabetes medications |

|

|

| Blood pressure and cholesterol medications | High blood pressure and high cholesterol medications |

|

|

| Stress and your health | Stress and your health |

|

|

| Practice and planning for the future, part 1 | No new videos, re-watch videos as needed |

|

|

| Practice and planning for the future, part 2 | No new videos, re-watch videos as needed |

|

|

| 2 Monthly maintenance sessions | No new videos, re-watch videos as needed |

|

|

| Final monthly maintenance session | No new videos, re-watch videos as needed |

|

|

For intervention fidelity, study staff conducted biweekly one-on-one meetings with peer coaches to monitor the progress of each client and reinforced program protocols. Staff also recorded and assessed a random number of sessions using a checklist. If any implementation issues arose, they were addressed during the bi-weekly peer coach group calls or individually with the peer coach, depending on the issue. In addition, since the peer coach received a peer coach manual and client plan book for each participant, these materials served as a record of the contacts between peer coaches and their participants. Peer coaches recorded the dates and start and end times for completed sessions; the results of the participant's home monitoring; and the participant's goals, barriers to achieving those goals, and plans for overcoming those barriers. Thus, study staff monitored intervention fidelity through several methods.

2.4. Participant recruitment and data collection

To be eligible for the trial, participants had to be community-dwelling adults aged 18 years or older who had been told by a doctor or nurse they had diabetes, were taking oral medications for diabetes, were non-adherent with their medications or wanted help taking their medications, and were under the care of a primary care doctor. Individuals were excluded if they did not wish to work with a peer coach, did not have a primary care doctor, had an end stage medical condition with limited life expectancy, and planned to move out of the area within the next six months. Participants were recruited using chain-referral sampling [31] and by presenting the study at community events, health fairs, and churches. Furthermore, flyers were posted at local medical offices, churches, libraries, stores, and other community meeting locations. Individuals who were eligible to participate were asked to refer individuals in their social networks. All interested community members spoke to study staff on the telephone and were provided details regarding the study, given the opportunity to ask questions, and then, if interested, were screened for study eligibility. Data collection occurred at baseline and at six months with an in-person visit in the participant's home or nearby community location to collect physiologic data, plus a 45-min telephone interview. Participants received a portable DVD player and a $20 gift card for participating in the study. The DVD player was used by the participants to watch the educational videos corresponding to their assigned study arm. All participants provided written informed consent. The study protocol was approved by the University Institutional Review Board.

2.5. Process measures

Peer coach and program evaluation questions were collected during final data collection at 6 months after baseline. Program staff contacted peer coaches bi-weekly during the implementation period and obtained data regarding intervention progress and barriers to program completion for each participant. Furthermore, the peer coach manuals and client plan books used by the peer coaches to record intervention progress and session details for each participant were collected at the end of the study.

3. Results

3.1. Peer coach recruitment and training

Nineteen peer coaches completed training and certification. During the implementation period, three peer coaches dropped out (two coaches due to health reasons and one coach due to increase in work responsibilities). The Living Well with Diabetes intervention was delivered between April 2014 and November 2018.

Peer coaches were matched with an average of 14 participants over the intervention implementation period. Peer coaches dictated the number of participants with whom they wished to work at any one time, with most coaches opting for three to six participants at a time.

3.2. Recruitment and trial participants

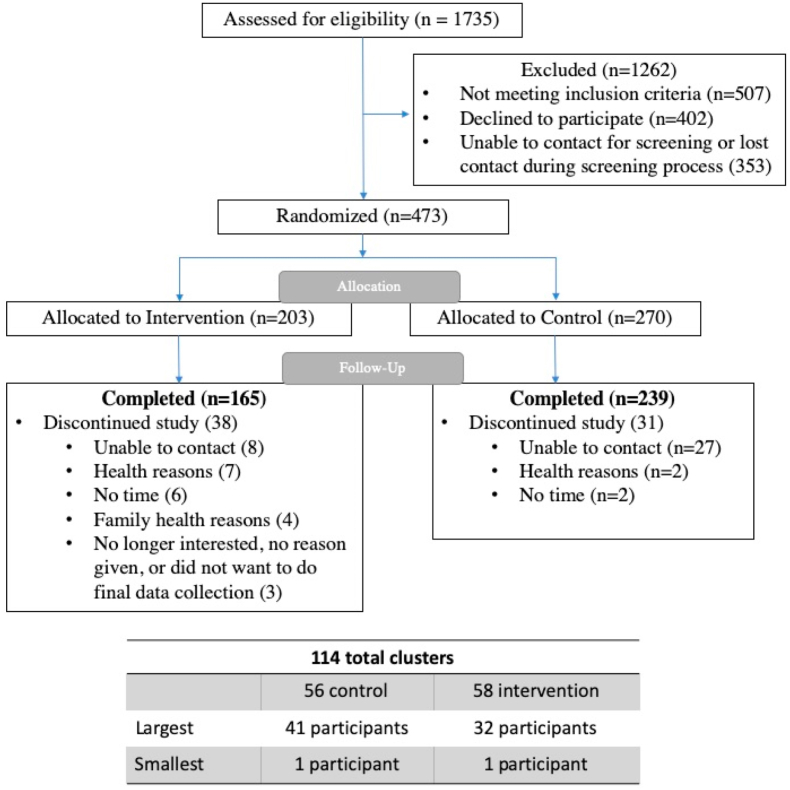

The trial enrolled 473 individuals, with 203 participants allocated to the intervention group and 270 to the control group (Fig. 1). The imbalance in participants by study group reflected variability in recruitment rates by cluster.

Fig. 1.

Living Well with Diabetes trial consort diagram.

Participants were 78% women, 91% African Americans, 56% had High School education or less, 70% had an annual income of less than $20,000, and 73% were not working at the time of enrollment (Table 4). Forty-four percent were taking insulin in addition to oral diabetes medications. One hundred sixty-five of 203 (81%) intervention participants and 239 of 270 (89%) control participants completed the trial. Of the 473 participants enrolled, 85% completed 6-month follow-up. There were no significant differences in baseline characteristics between trial completers and noncompleters.

Table 4.

Baseline characteristics of Living Well with Diabetes trial participants.

| Characteristic | ALL N = 473 | Control N = 270 | Intervention N = 203 | Pa |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean ± SD | 57.1 ± 11.5 | 56.7 ± 12.1 | 57.7 ± 10.6 | .35 |

| Women, n (%) | 371 (78.4) | 212 (78.5) | 159 (78.3) | .96 |

| Race, n (%) | .07 | |||

| African American | 428 (90.5) | 250 (92.6) | 178 (87.7) | |

| All others | 45 (9.5) | 20 (7.4) | 25 (12.3) | |

| Marital Status | .65 | |||

| Married or living with partner | 169 (35.8) | 94 (34.9) | 75 (37.0) | |

| Never married, divorced, widowed, separated | 303 (64.2) | 175 (65.1) | 128 (63.0) | |

| Annual income, n (%) | .56 | |||

| <$20,000 | 318 (70.4) | 185 (71.4) | 133 (69.0) | |

| ≥$20,000 | 134 (29.6) | 74 (28.6) | 60 (31.0) | |

| Education, n (%) | .58 | |||

| <High School | 97 (20.6) | 51 (18.9) | 46 (22.8) | |

| High Schoolb | 168 (35.6) | 99 (36.7) | 69 (34.2) | |

| >High School | 207 (43.9) | 120 (44.4) | 87 (43.1) | |

| Employment, n (%) | .88 | |||

| Employed for wages or self employed | 125 (26.6) | 72 (26.9) | 53 (26.2) | |

| Not working (retired, out of work, homemaker, unable to work) | 345 (73.4) | 196 (73.1) | 149 (73.8) |

T-test or chi square testing between-group differences.

12nd grade, GED, or High School diploma.

Results of the Process Evaluation of the Living Well Intervention

Of the 203 participants randomized to the intervention, 166 (81.8%) completed all sessions of the program and 174 (85.7%) completed at least the six-session intensive intervention phase. Of the 165 intervention participants who completed follow-up data collection, 154 (93.3%) completed all sessions of the program. The most frequent reasons given for discontinuing the study were health reasons, not having time for the program, having a change in a family member's health, or no longer being interested in participating in the study (Fig. 1).

For the 165 intervention participants who completed follow-up data collection, 93% reported that their peer coaches were easy to talk with, 95% reported that the support they received from their peer coach was great or good, and 92% reported that they felt comfortable with their peer coach. Moreover, 93% reported that their peer coach knew the program well and 93% reported that they would recommend a peer coach to a friend or a relative with a similar health condition. Finally, in regards to the program, 95% reported that they were extremely satisfied or satisfied, 91% reported that they used the program materials and found them helpful, and 96% reported that they watched the program videos and found the information helpful.

4. Discussion

Using an interactive and iterative collaborative approach with our community partners, we developed and implemented an engaging peer coaching storytelling intervention based on social cognitive theory and guided by the Chronic Illness Trajectory model to improve diabetes medication adherence and self-management behaviors. The trial testing this intervention recruited 473 participants, with 404 (85%) participants completing follow-up data collection. Among the 165 participants in the intervention arm who completed follow-up data collection, 93% completed all program sessions, reflecting a high level of engagement. Intervention participants expressed high satisfaction with the program materials and their interactions with their peer coaches.

Although peer coaching and storytelling separately have been found to be acceptable and effective in helping patients with chronic conditions to make behavioral changes [[32], [33], [34], [35]], our study is one of the first to use both peer coaching and storytelling to help diabetic individuals integrate self-management tasks into their daily lives. Storytelling has been used effectively as a patient-centered tool for engaging individuals in their self-management [32,[36], [37], [38], [39]]. In the Living Well with Diabetes intervention, peer coaches used the storytelling videos as a starting point to help participants explore their own story of coming to terms with their illness and view the importance of medication taking and other self-care for living meaningfully, with hopes and aspirations for the future.

Our intervention development and implementation approach has several strengths. The intervention was built on an existing well-established collaboration with community partners, ensuring that the program design, delivery, and protocols were acceptable and feasible within the community. These partnerships deepened the study team's understanding of community priorities and enabled the team to develop messaging around medication taking that was acceptable and engaging to community members. For example, formative work with community partners revealed strong interest in help with lifestyle modification but less interest with medication adherence interventions. In fact, beliefs emerged that medications were viewed as a “last resort,” and use of medications was seen as a personal failure, because the individual had been unable control diabetes with exercise and diet [40]. Thus, the storytelling videos and peer support interactions discussed disease trajectory and the progressive nature of diabetes and emphasized medication as an essential tool to be used in conjunction with lifestyle changes. However, because lifestyle support was an important priority for participants, the program provided education and behavioral strategies for diet and exercise alongside support for medication taking. Another strength of the program was its telephonic delivery, which was designed to reach and retain individuals that may have limited access to similar programs. Rather than asking participants to attend in-person education sessions, we provided content via video, enabling standardized delivery of patient-friendly education delivered by health professionals. Participants and peer coaches were paired with each other based on mutual availability, to facilitate flexibility in scheduling. We also increased intervention reach by making data collection as convenient as possible for the participant, either conducting the in-person visit at the participant's home or meeting them at a location nearby.

Some limitations of our approach are also worth noting. Process outcomes were available only for those who completed the intervention and the final data collection visit. We also had to rely on self-report for self-care behaviors. Also, many community members had limited access to high speed internet and/or reliable phone service with enough minutes for the telephone sessions, so participants received a portable DVD player as an incentive and a cell phone to use during the intervention period, if needed. Thus, this is a potential challenge for intervention dissemination if the study is found to be effective. Finally, we engaged mostly women, possibly limiting generalizability of the engagement of this intervention for men. The stories in our videos were told by Black Belt community members, thus the homophily achieved with our participants may not be as intense for other communities. Most of our participants did not work, thus this intervention may not be as suitable for a working population.

In conclusion, the Living Well with Diabetes intervention was developed and implemented successfully using a community-partnered approach to intervention development for use in high-need communities in Alabama. The intervention engaged participants in over 80% follow-up in the intervention arm, and of those, 86% completing at least the six intensive intervention sessions, and 82% completing all sessions. Study participants who completed the study were highly satisfied with the intervention program and with their interactions with their peer coach. The strategies used by our study team to develop and implement this program in close collaboration with our peer coaches and community members may be useful to other communities seeking to develop and provide an engaging, patient-centered medication adherence program to individuals living with diabetes.

Funding

Research reported in this article was funded through a Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI) Award AD-1306-03565-IC.

The statements in this article are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI), its Board of Governors or Methodology Committee.

Contributor Information

Susan J. Andreae, Email: sandreae@wisc.edu.

Lynn J. Andreae, Email: landreae@uabmc.edu.

Andrea Cherrington, Email: acherrington@uabmc.edu.

Joshua Richman, Email: jrichman@uabmc.edu.

Monika Safford, Email: mms9024@med.cornell.edu.

References

- 1.Krass I., Schieback P., Dhippayom T. Adherence to diabetes medication: a systematic review. Diabet. Med. 2015;32(6):725–737. doi: 10.1111/dme.12651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Iglay K., Cartier S.E., Rosen V.M., Zarotsky V., Rajpathak S.N., Radican L., Tunceli K. Meta-analysis of studies examining medication adherence, persistence, and discontinuation of oral antihyperglycemic agents in type 2 diabetes. Curr. Med. Res. Opin. 2015;31(7):1283–1296. doi: 10.1185/03007995.2015.1053048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Capoccia K., Odegard P.S., Letassy N. Medication adherence with diabetes medication: a systematic review of the literature. Diabetes Educat. 2016;42(1):34–71. doi: 10.1177/0145721715619038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Odegard P.S., Capoccia K. Medication taking and diabetes: a systematic review of the literature. Diabetes Educat. 2007;33(6):1014–1029. doi: 10.1177/0145721707308407. discussion 1030-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sokol M.C., McGuigan K.A., Verbrugge R.R., Epstein R.S. Impact of medication adherence on hospitalization risk and healthcare cost. Med Care. 2005;43(6):521–530. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000163641.86870.af. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Asche C., LaFleur J., Conner C. A review of diabetes treatment adherence and the association with clinical and economic outcomes. Clin. Therapeut. 2011;33(1):74–109. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2011.01.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cutler R.L., Fernandez-Llimos F., Frommer M., Benrimoj C., Garcia-Cardenas V. Economic impact of medication non-adherence by disease groups: a systematic review. BMJ Open. 2018;8(1) doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-016982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Egede L.E., Gebregziabher M., Echols C., Lynch C.P. Longitudinal effects of medication nonadherence on glycemic control. Ann. Pharmacother. 2014;48(5):562–570. doi: 10.1177/1060028014526362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cramer J.A., Benedict A., Muszbek N., Keskinaslan A., Khan Z.M. The significance of compliance and persistence in the treatment of diabetes, hypertension and dyslipidaemia: a review. Int. J. Clin. Pract. 2008;62(1):76–87. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-1241.2007.01630.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pladevall M., Williams L.K., Potts L.A., Divine G., Xi H., Lafata J.E. Clinical outcomes and adherence to medications measured by claims data in patients with diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2004;27(12):2800–2805. doi: 10.2337/diacare.27.12.2800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Conn V.S., Ruppar T.M. Medication adherence outcomes of 771 intervention trials: systematic review and meta-analysis. Prev. Med. 2017;99:269–276. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2017.03.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nam S., Chesla C., Stotts N.A., Kroon L., Janson S.L. Barriers to diabetes management: patient and provider factors. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2011;93(1):1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2011.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hugtenburg J.G., Timmers L., Elders P.J., Vervloet M., van Dijk L. Definitions, variants, and causes of nonadherence with medication: a challenge for tailored interventions. Patient Prefer. Adherence. 2013;7:675–682. doi: 10.2147/PPA.S29549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Williams J.L., Walker R.J., Smalls B.L., Campbell J.A., Egede L.E. Effective interventions to improve medication adherence in Type 2 diabetes: a systematic review. Diabetes Manag. 2014;4(1):29–48. doi: 10.2217/dmt.13.62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sapkota S., Brien J.A., Greenfield J.R., Aslani P. A systematic review of interventions addressing adherence to anti-diabetic medications in patients with type 2 diabetes--components of interventions. PloS One. 2015;10(6) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0128581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Corbin J.M. The corbin and strauss chronic illness trajectory model: an update. Sch. Inq. Nurs. Pract. 1998;12(1):33–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Corbin J., Strauss A. Managing chronic illness at home: three lines of work. Qual. Sociol. 1985;8(3):224–247. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Corbin J., Strauss A. Jossey-Bass; San Francisco, CA: 1988. Unending Work and Care: Managing Chronic Illness at Home. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bandura A. Health promotion by social cognitive means. Health Educ. Behav. 2004;31(2):143–164. doi: 10.1177/1090198104263660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Evans B.C., Crogan N.L., Bendel R. Storytelling intervention for patients with cancer: part 1--development and implementation. Oncol. Nurs. Forum. 2008;35(2):257–264. doi: 10.1188/08.ONF.257-264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Houston T.K., Allison J.J., Sussman M., Horn W., Holt C.L., Trobaugh J., Salas M., Pisu M., Cuffee Y.L., Larkin D., Person S.D., Barton B., Kiefe C.I., Hullett S. Culturally appropriate storytelling to improve blood pressure: a randomized trial. Ann. Intern. Med. 2011;154(2):77–84. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-154-2-201101180-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hoybye M.T., Johansen C., Tjornhoj-Thomsen T. Online interaction. Effects of storytelling in an internet breast cancer support group. Psycho Oncol. 2005;14(3):211–220. doi: 10.1002/pon.837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tl W. The Encyclopedia of Alabama; 2009. Black Belt Region in Alabama. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Webster G.R., Bowman J. Quantitiatively delineating the Black Belt geographic region. Southeastern geographer. SE. Geogr. 2008;48(1):3–18. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Annual Estimates of the Resident Population by Sex, Race, and Hispanic Origin for the United States, States, and Counties: April 1, 2010 to July 1, 2018. 2019. http://bit.ly/ALBlackBelt [Google Scholar]

- 26.Professionally Active Physicians . 2019. State Health Facts.https://www.kff.org/other/state-indicator/total-active-physicians/?currentTimeframe=0&sortModel=%7B%22colId%22:%22Location%22,%22sort%22:%22asc%22%7D [Google Scholar]

- 27.Underlying Cause of Death 1999-2017, CDC WONDER. https://wonder.cdc.gov/wonder/help/ucd.html#

- 28.Andreae S.J., Andreae L.J., Cherrington A.L., Lewis M., Johnson E., Clark D., Safford M.M. Development of a community health worker-delivered cognitive behavioral training intervention for individuals with diabetes and chronic pain. Fam. Community Health. 2018;41(3):178–184. doi: 10.1097/FCH.0000000000000197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cherrington A., Martin M.Y., Hayes M., Halanych J.H., Wright M.A., Appel S.J., Andreae S.J., Safford M. Intervention mapping as a guide for the development of a diabetes peer support intervention in rural Alabama. Prev. Chronic Dis. 2012;9:E36. doi: 10.5888/pcd9.110053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Safford M.M., Andreae S., Cherrington A.L., Martin M.Y., Halanych J., Lewis M., Patel A., Johnson E., Clark D., Gamboa C., Richman J.S. Peer coaches to improve diabetes outcomes in rural Alabama: a cluster randomized trial. Ann. Fam. Med. 2015;13(Suppl 1):S18–S26. doi: 10.1370/afm.1798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Heckathorn D. Respondent-driven sampling: a new approach to the study of hidden populations. Soc. Probl. 1997;44(2):174–199. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Utz S.W., Williams I.C., Jones R., Hinton I., Alexander G., Yan G., Moore C., Blankenship J., Steeves R., Oliver M.N. Culturally tailored intervention for rural African Americans with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Educat. 2008;34(5):854–865. doi: 10.1177/0145721708323642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gucciardi E., Richardson A., Aresta S., Karam G., Sidani S., Beanlands H., Espin S. Storytelling to support disease self-management by adults with type 2 diabetes. Can. J. Diabetes. 2019;43(4):271–277 e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jcjd.2018.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Njeru J.W., Patten C.A., Hanza M.M., Brockman T.A., Ridgeway J.L., Weis J.A., Clark M.M., Goodson M., Osman A., Porraz-Capetillo G., Hared A., Myers A., Sia I.G., Wieland M.L. Stories for change: development of a diabetes digital storytelling intervention for refugees and immigrants to Minnesota using qualitative methods. BMC Publ. Health. 2015;15:1311. doi: 10.1186/s12889-015-2628-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bertera E. Storytelling slide shows to improve diabetes and high blood pressure knowledge and self-efficacy: three-year results among community dwelling older african Americans. Educ. Gerontol. 2014;40(11):785–800. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gucciardi E., Jean-Pierre N., Karam G., Sidani S. Designing and delivering facilitated storytelling interventions for chronic disease self-management: a scoping review. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2016;16:249. doi: 10.1186/s12913-016-1474-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Williams I.C., Utz S.W., Hinton I., Yan G., Jones R., Reid K. Enhancing diabetes self-care among rural African Americans with diabetes: results of a two-year culturally tailored intervention. Diabetes Educat. 2014;40(2):231–239. doi: 10.1177/0145721713520570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Greenhalgh T., Collard A., Campbell-Richards D., Vijayaraghavan S., Malik F., Morris J., Claydon A. Storylines of self-management: narratives of people with diabetes from a multiethnic inner city population. J. Health Serv. Res. Pol. 2011;16(1):37–43. doi: 10.1258/jhsrp.2010.009160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Leeman J., Skelly A.H., Burns D., Carlson J., Soward A. Tailoring a diabetes self-care intervention for use with older, rural African American women. Diabetes Educat. 2008;34(2):310–317. doi: 10.1177/0145721708316623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Andreae L.J., Andreae S.J., Safford M.M. Medication-related beliefs in rural African American with diabetes. Ann. Behav. Med. 2015;49:s182. [Google Scholar]