Abstract

This case-control study examines the rates of refills under 2 separate strategies for opioid prescribing after operations in a hepatopancreatobiliary surgery department.

State-specific limits on total days and procedure-specific recommendations of discharge opioid volumes have had mixed success in mitigating postoperative opioid dissemination.1,2 Most prescribers still expose their clinician-specific bias in writing round numbers of opioid doses (eg, 30-50 pills). In the theme of patient-centered care, this study analyzed oncologic surgery discharge opioid prescriptions and 30-day refills when a novel, patient-centered prescription calculation was implemented.

Methods

Based on a US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention report3 showing a salient inflection point in the association of initial opioid prescription volume with long-term opioid dependence at 5 days’ supply, we created a simple 5× multiplier, wherein patients received 5 times the amount of their opioid use in the last 24 inpatient hours (eg, 2 pills × 5 = 10 pills; 0 pills × 5 = 0 pills). Beginning with clinician education sessions in August 2018, this patient-centered calculation was voluntarily and gradually adopted by an increasing proportion of hepatopancreatobiliary (HPB) clinicians.4 This was a nonrandomized cohort study of consecutive HPB operations at MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston, Texas, conducted from September 2018 through June 2019. It was approved by the MD Anderson Cancer Center institutional review board, with a waiver of informed consent because the study activities were part of usual patient care.

Two prescribing patterns emerged: patients in the usual care (UC) group, who received clinician-specific opioid pill volumes, vs patients who received 5× multiplier–compliant volumes. Actual oral morphine equivalents (OMEs) were converted using institution-approved values. Refills were trackable in the electronic medical record. Continuous variables were compared using Mann-Whitney U test, and categorical variables were compared using χ2 test or Fisher exact test, as appropriate. The threshold for statistical significance was P < .05, with all tests 2-sided. All tests were performed with SPSS version 22 (IBM).

Results

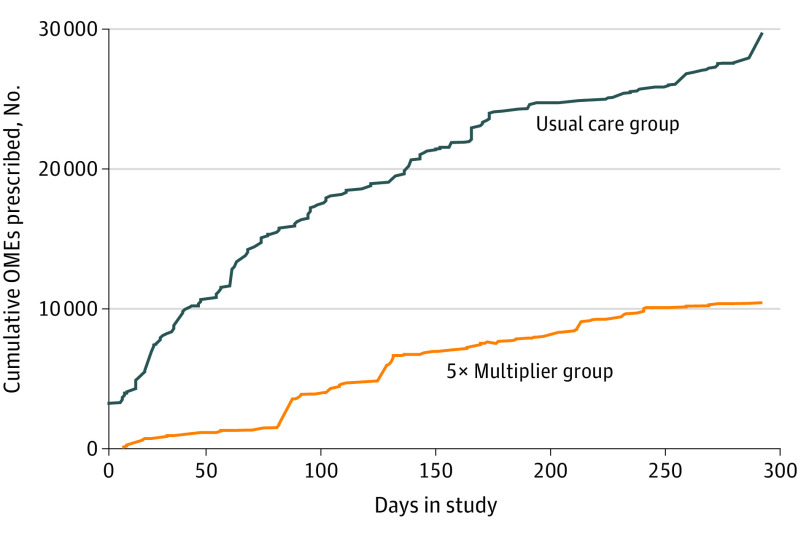

There were 278 consecutive elective HPB tumor resections by 9 faculty surgeons in 10 months. Operations included 152 liver resections (54.7%) and 126 pancreas resections (45.3%), with 125 patients (45.0%) receiving 5×-multiplier dosing. Other than slight differences in regional nerve block use (72 [47.1%] vs 75 [60.0%]; P = .03), both groups had similar clinical characteristics, including length of hospital stay and use of opioid-weaning nonopioid bundles (Table). Median OMEs consumed in the last 24 inpatient hours were 10 mg for both groups (interquartile ranges [IQRs], UC group: 5-20 mg; 5× multiplier, 0-20 mg). Median (IQR) discharge prescription OMEs were 150 (100-150) mg for UC vs 50 (0-100) mg in the 5×-multiplier group (P < .001). The cumulative volume curve of OMEs disseminated was notably flattened in the 5×-multiplier group (Figure).

Table. Comparison of Patient Characteristics Managed in Usual Care and 5×-Multiplier Pathways.

| Characteristic | Patients, No. (%) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Usual care (n = 153) | 5× Multiplier (n = 125) | ||

| Age, median (IQR), y | 58.3 (48.4-68.6) | 59.2 (49.6-68.5) | .62a |

| BMI | 25.8 (22.8-29.6) | 26.5 (22.8-29.9) | .64a |

| Female | 74 (48.4) | 59 (47.2) | .85 |

| Preoperative opioids | 29 (22.6) | 12 (18.4) | .03 |

| Liver operation | 88 (57.5) | 64 (51.2) | .29 |

| Laparoscopic or robotic operation | 24 (15.6) | 22 (17.6) | .67 |

| Combination operationb | 14 (9.2) | 19 (15.2) | .12 |

| Regional nerve block | 72 (47.1) | 75 (60.0) | .03 |

| Epidural | 46 (30.1) | 27 (21.6) | .11 |

| Major complication | 28 (18.3) | 15 (12.0) | .15 |

| Readmission | 28 (18.3) | 18 (14.4) | .38 |

| ≥2 Nonopioid medications bundled with opioidsc | 122 (79.7) | 97 (77.6) | .66 |

| Length of stay, median (IQR), d | 4 (3-6) | 5 (3-6) | .52a |

| Refills within 30 d | 32 (20.9) | 21 (16.8) | .39 |

| OMEs in last 24 h, median (IQR), mg | 10 (5-20) | 10 (0-20) | .36a |

| Initial discharge OMEs, median (IQR), mg | 150 (100-150) | 50 (0-100) | <.001a |

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index (calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared); IQR, interquartile range; OME, oral morphine equivalents.

Mann-Whitney U test.

A combination operation consists of a second organ resected or a concomitant ventral hernia repair.

Nonopioid medications include acetaminophen, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, muscle relaxers, and gabapentinoids.

Figure. Cumulative Opioids Prescribed by Usual Care vs 5×-Multiplier Groups.

The curves represent the difference in opioid dissemination to the community that can be avoided by using the 5×-multiplier dosage strategy. The curves would likely separate more as time goes on. OME indicates oral morphine equivalents.

Thirty-day opioid refill rates were similar between groups (UC group, 32 [20.9%] vs 5×-multiplier group, 21 [16.8%]; P = .39). Sixty-nine patients (24.8%) were already weaned to no opioid use in the last 24 hours of hospitalization, but 31 (45%) were still discharged with opioids (UC). Among the 69 patients who had used no opioids in their last 24 inpatient hours, none subsequently received an outpatient opioid prescription. Among the 15 patients who received at least 1 opioid pill but an amount less than the 5×-multiplier dosage, 8 (53%) required a refill.

Discussion

In patients undergoing curative-intent oncologic surgery, a novel, patient-centered 5× multiplier of last 24 hours of inpatient opioid use reduced discharge opioid prescriptions by 67% over UC, with no increase in 30-day refill rates. No patients who used 0 mg of opioids in the 24 hours prior to discharge received refills of opioid pain medications. Patients already weaned down to 0 mg of opioids by the last 24 hours before discharge could be safely assumed to not need outpatient opioids.

Even as more clinicians acknowledge the desire to abandon the antiquated model of clinician-specific volume calculations and try to adopt a procedure-specific model, the discharging clinician still has the ability to supersede any recommended range based on clinical instinct, fear of refill logistics, opioid education bias, and/or perceived empathy for the patient.1,4,5,6 Writing discharge opioid prescriptions based on each patient’s actual opioid use overcomes clinician bias, is patient centered, and markedly decreases the trajectory of cumulative opioid dissemination to the community (Figure).

Study limitations include the nonrandomized design and the voluntary rollout of the 5× multiplier by advanced practice clinicians and fellows in the study period. Despite these study limitations, the major strength of the 5× multiplier is that it does not require any special online or smartphone calculator or pain team consultation. It complies with all current state laws and US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention guidelines. Future prospective studies expanding to other types of surgery and comparing the patient-centered 5× multiplier with procedure-specific and state-specific guidelines are needed.

References

- 1.Chua KP, Kimmel L, Brummett CM. Disappointing early results from opioid prescribing limits for acute pain. JAMA Surg. 2020. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2019.5891 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Porter SB, Glasgow AE, Yao X, Habermann EB. Association of Florida House Bill 21 with postoperative opioid prescribing for acute pain at a single institution. JAMA Surg. 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mundkur ML, Franklin JM, Abdia Y, et al. Days’ supply of initial opioid analgesic prescriptions and additional fills for acute pain conditions treated in the primary care setting—United States, 2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019;68(6):140-143. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6806a3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lillemoe HA, Newhook TE, Vreeland TJ, et al. Educating surgical oncology providers on perioperative opioid use: results of a departmental survey on perceptions of opioid needs and prescribing habits. Ann Surg Oncol. 2019;26(7):2011-2018. doi: 10.1245/s10434-019-07321-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Howard R, Vu J, Lee J, Brummett C, Englesbe M, Waljee J. A pathway for developing postoperative opioid prescribing best practices. Ann Surg. 2020;271(1):86-93. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000003434 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Overton HN, Hanna MN, Bruhn WE, Hutfless S, Bicket MC, Makary MA; Opioids After Surgery Workgroup . Opioid-prescribing guidelines for common surgical procedures: an expert panel consensus. J Am Coll Surg. 2018;227(4):411-418. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2018.07.659 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]