Abstract

Mitochondrial neurogastrointestinal encephalomyopathy (MNGIE) is a rare autosomal-recessive multisystemic disorder with predominant gastrointestinal involvement, presenting with variable degrees of gut dysmotility up to frank chronic intestinal pseudo-obstruction. Despite major advances in understanding its basic molecular pathogenesis in recent years, the distinct mechanisms and pathoanatomical substrate underlying MNGIE-associated gastrointestinal dysmotility are still widely unknown. As yet, though their critical role in proper gastrointestinal transit in terms of spontaneous pacemaker activity and enteric neurotransmission is well established, the population of the interstitial cells of Cajal (ICC) has not been investigated in MNGIE. Therefore, we examined small bowel samples of a well-characterized MNGIE patient by using conventional histology and immunohistochemistry techniques. The ICC network was studied by immunohistochemistry for the tyrosine kinase Kit (CD117), known to reliably detect ICCs, while mucosal mast cells served as an internal and normal small bowel specimen as external controls. At a light microscopic level, no gross structural alteration of the bowel wall composition and its neuromuscular elements was noted. However, a complete absence of Kit immuno-reactive cells could be demonstrated in regions where ICCs are normally abundant, while internal and external controls retained strong Kit positivity. In conclusion, our preliminary results provide a first evidence for an alteration of the ICC network in MNGIE, and support the notion that ICC loss might be an early pathogenetic event in MNGIE-associated gut motor dysfunction before significant myopathic and/or neuropathic structural changes occur.

Keywords: chronic intestinal pseudoobstruction, interstitial cells of Cajal, mitochondrial neurogastrointestinal encephalomyopathy

INTRODUCTION

Mitochondrial neurogastrointestinal encephalomyopathy (MNGIE) is a rare autosomal-recessive multisystemic disorder, characterized by gastrointestinal dysmotility, cachexia, ptosis/external ophthalmoplegia, peripheral neuropathy and cerebral white matter changes on magnetic resonance imaging.1 Loss-of-function mutations in the nuclear gene TYMP encoding cytosolic thymidine phoshorylase (TP, alternatively referred to as endothelial cell growth factor 1) cause pathologic systemic accumulation of thymidine (dThd) and deoxyuridine (dUrd). Unbalanced pyrimidine nucleoside pools, in their turn, are thought to impair mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) replication and structural integrity, provoking somatic mtDNA alterations (depletion, deletions and site-specific point mutations).2–4 While substantial progress in understanding basic molecular events in MNGIE has been achieved over the last decade, there is still considerable uncertainty as to the specific pathogenetic mechanisms and histopathological substrate underlying the predominant gastrointestinal involvement, which often presents clinically as overt chronic intestinal pseudoobstruction (CIP). The central role of the network of the interstitial cells of Cajal (ICC – named after the neuroscientist Santiago Ramon y Cajal 1852–1934) in regulating gut motor function as intrinsic pacemaker cells and intermediaries of enteric neurotransmission is well established.5 Rarefication to outright absence of ICCs, either in isolation or in conjunction with disturbances of other elements of the enteric neuromuscular interface, has been linked to a variety of gastrointestinal motility disorders, including certain subpopulations of CIP patients, and might, therefore, be an attractive candidate in mediating gastrointestinal dysmotility in MNGIE.6–8 Hence, we performed immunohistochemical studies of ICCs in small bowel samples of a patient with biochemically and genetically proven MNGIE.

CASE REPORT

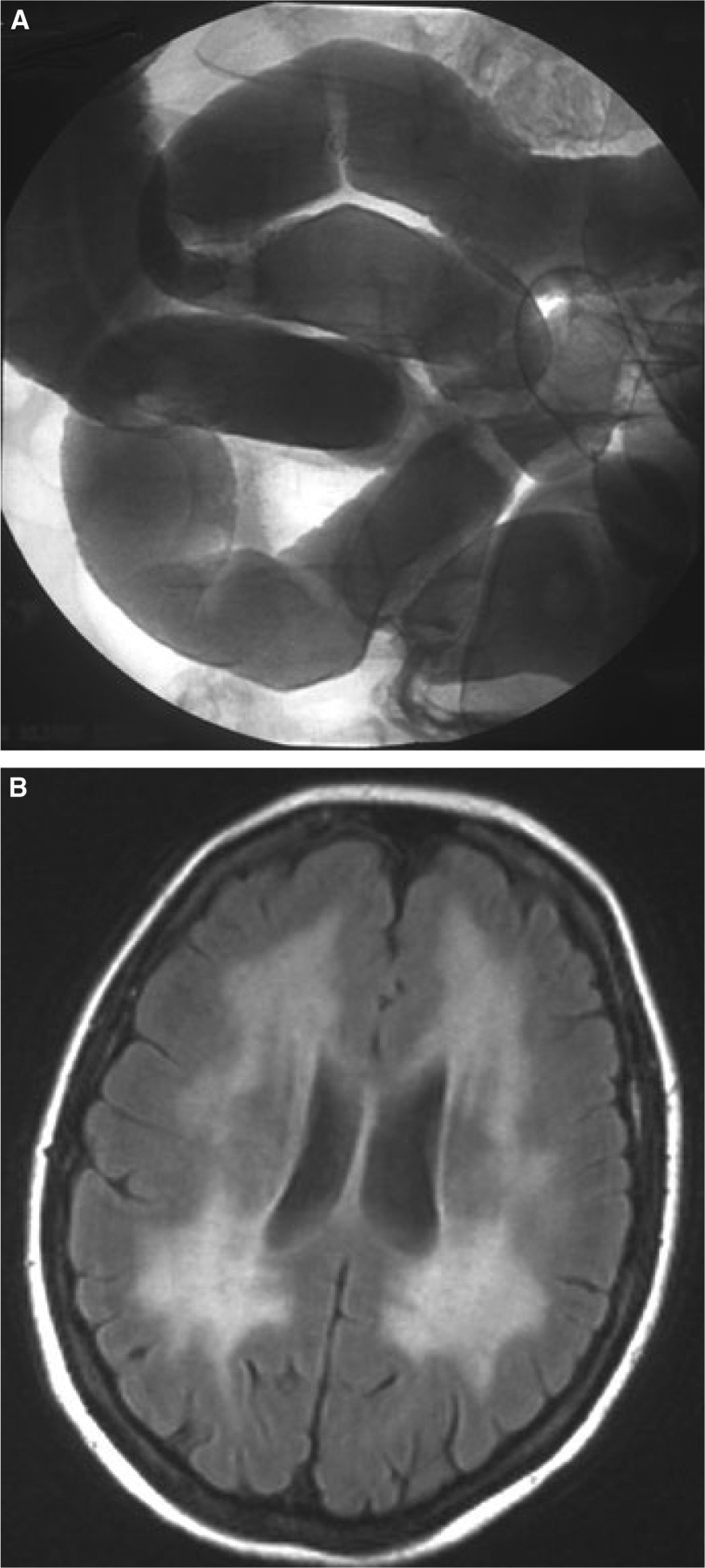

A 35-year-old woman was referred for further work-up of longstanding diarrhoea and profound cachexia (31 kg/160 cm: body mass index 12.1 kg m−2; maximum weight 47 kg). Repeated prior gastroenterological evaluations over a period of 4 years had failed to reach a conclusive diagnosis. On admission, the patient showed clinical and laboratory signs of malabsorption (hypoproteinaemia, pitting ankle oedema, slightly reduced beta-carotene levels, and deficiencies of multiple vitamins and trace elements), while passing three to five soft stools daily. Bidirectional endoscopy and mucosal histology yielded non-specific results. However, enteroclysis was significant for a markedly delayed small bowel transit with sporadic, largely nonpropulsive contractions and a severe reduction of the plicae circulares, leading us to provisionally diagnose CIP (Fig. 1A). Gastric emptying scintigraphy, using a 99 m-Tc radiolabelled oatmeal meal, indicated only a minor prolongation of gastric transit (gastric emptying half-time: 35 min; normal ≤ 30), further supporting predominant small bowel dysmotility. Neurological examination showed overt left-sided ptosis with horizontal external ophthalmoplegia, mild stocking-glove sensory loss with distal limb weakness and reduced tendon reflexes. Neurophysiological studies were consistent with a mixed, peripheral neuropathy. The clinical presentation in association with repeatedly elevated serum lactate levels prompted us to perform a lactate stress test, suggestive of mitochondrial dys-function.9 Cerebral MRI was significant for advanced periventricular symmetrical white matter hyperintensities (Fig. 1B). Hence, the patient clinically fulfilled diagnostic criteria for MNGIE. Plasma nucleoside levels were found to be significantly elevated: dUrd 11.3 μmol L−1 and dThd 3.9 μmol L−1, normal <0.05 μmol L−1 each. TP activity in buffy coat was severely reduced to 12 nmol h−1 mg−1-protein (normal 634 ± 217 mean ± SD).10 Sequencing of the TYMP gene revealed compound heterozygous point mutations (c.261G > T and c.340G > A), causing amino acid substitutions at position 87 (glutamate to aspartate) and at position 114 (asparate to asparagine).

Figure 1.

(A) Conventional enteroclysis demonstrating severe reduction of the plicae circulares in a shapeless, non-dilated small bowel. (B) Cerebral fluid-attenuated inversion recovery MRI revealing diffuse symmetrical hyperintensities of the periventricular white matter.

PATHOLOGICAL STUDIES

Formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissue from a full-thickness biopsy of the jejunum, obtained during mini-laparoscopy prior to establishing the diagnosis of MNGIE, was available for conventional histology and immunohistochemistry studies.

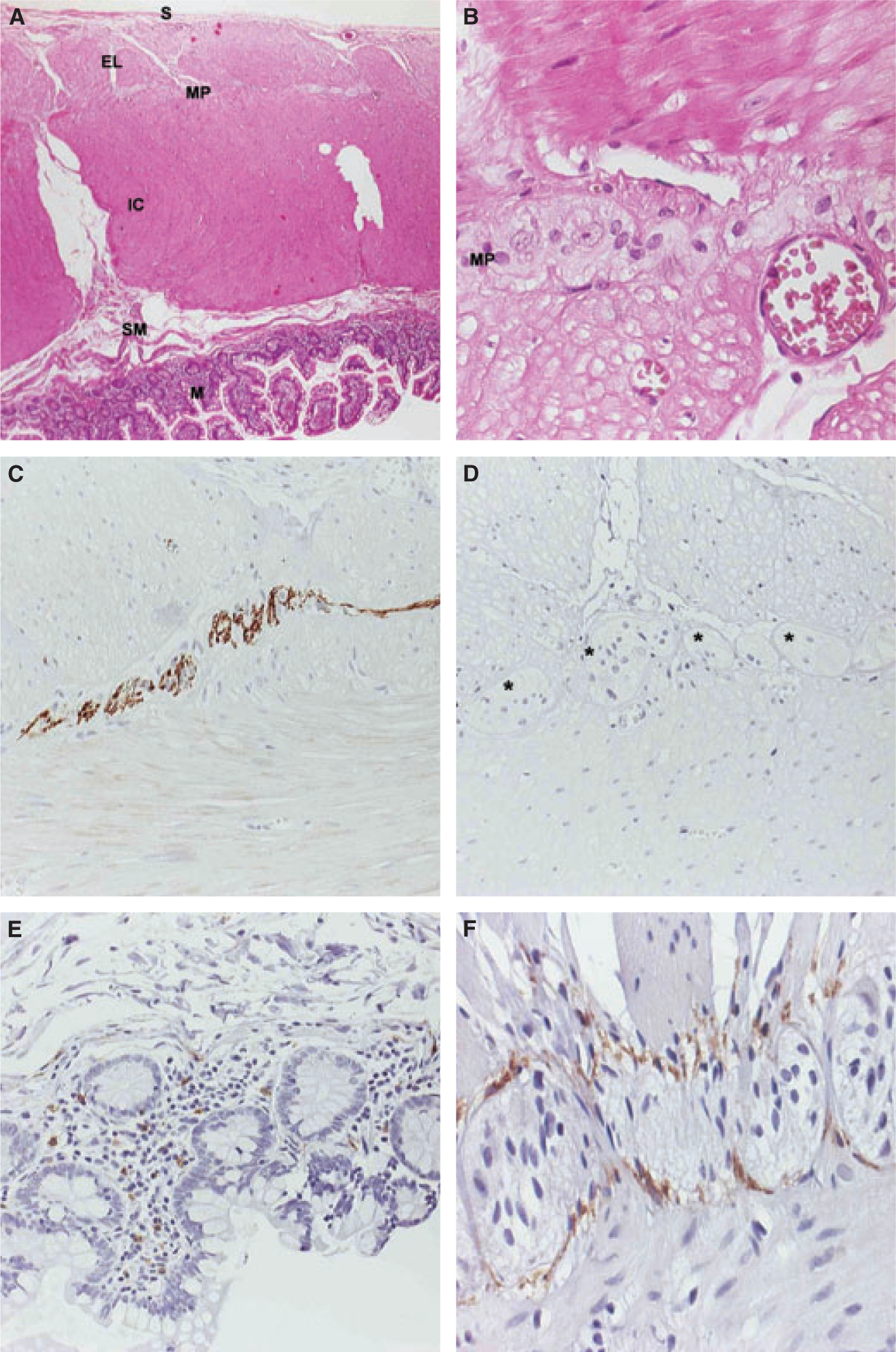

Haematoxylin and eosin and elastic-Van Gieson staining revealed no gross structural alterations with a normal layer composition of the small bowel wall on light microscopy (Fig. 2A). There was neither significant villous atrophy nor any acute or chronic inflammatory infiltration within the bowel wall, which was further supported by normal findings with immunohistochemical stains for CD3, CD8, CD79 and CD68 (not shown). The nerve plexuses, in particular the myenteric plexus of Auerbach (Fig. 2B), showed normal neuronal cell content, distribution, and morphology by routine immunohistochemical stains for S-100 protein (not shown) and neurofilament A (Fig. 2C), indicating structural integrity of neuronal cells.

Figure 2.

(A) Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E). Gross morphology of the small bowel wall of our patient demonstrates a normal layer composition, consisting of the mucosa (M), the submucosa (SM), the inner circular layer (IC), the external longitudinal layer (EL) of the muscularis propria, with the myenteric plexus (MP) in between, and the serosa (S). (B) H&E. Higher magnification focusing on the MP. Enteric ganglia cells show normal cellular content, distribution, and morphology. (C) Immunohistochemistry (IHC) for Neurofilament A. Neuronal cells within the MP show a strong immunoreactivity, indicating neuronal structural integrity. (D) IHC for kit. No kit-positive cells can be detected around the MP, where interstitial cells of Cajal (ICCs) are normally abundant (asterixes). (E) IHC for kit. Mucosal mast cells in our patient retain kit positivity (internal control). (F) IHC for kit. There is a strong kit reactivity in ICCs in the circumference of the MP in a representative normal control specimen (external control).

To evaluate ICC populations in our patient, we performed an immunohistochemical analysis of the tyrosine kinase Kit (CD117), a receptor for stem cell factor (polyclonal rabbit anti-Kit antibody; Dako, Hamburg, Germany, dilution 1 : 400), employing routine pathological techniques. On careful examination of several histological sections, no Kit reactive cells could be identified in areas where ICCs are normally detected, for example ICCs related to the myenteric plexus (Fig. 2D). By contrast, mucosal mast cells of our patient retained prominent Kit staining, excluding artefactual loss of Kit immunoreactivity (Fig. 2E). In addition, small bowel specimen from patients without a history of inflammatory bowel disease or neuromuscular diseases obtained during abdominal surgery were strongly positive for Kit (Fig. 2F), serving as external controls.

DISCUSSION

Despite gastrointestinal dysmotility undoubtedly being the clinical hallmark of MNGIE, there is limited data addressing gut-specific pathogenetic aspects of the disease. In a recent postmortem study,11 atrophy, mitochondrial proliferation and mtDNA depletion in the external layer of the muscularis propria of small bowel samples have been attributed to visceral myopathy, which is in accordance with previous manometric and histopathological findings in MNGIE.12,13 Backed up by evidence of a constitutive reduction in mtDNA copy numbers relative to control small bowel specimen, it was hypothesized that there might be a pathoanatomical basis rendering the small intestine particularly susceptible to mtDNA disturbances in the context of TYMP gene mutations. Nevertheless, because these studies were performed on postmortem tissues, the visceral myopathy may be a feature of end-stage disease of MNGIE and may not fully account for the gastrointestinal dysmotility that is typically present for decades in patients.

In contrast to intestinal muscle and nerve plexuses, the ICC, comprising a diverse, ultrastructurally distinct category of cells derived from mesenchymal precursor cells14 have not been studied in MNGIE. As components of extensive networks of electrically and anatomically coupled cells, some subsets of ICCs are primarily engaged in integrating and mediating excitatory and inhibitory neurotransmission, whereas others provide autonomic rhythmicity by generation of spontaneously active pacemaker currents.15 Expression of and signalling through Kit has been shown to be vital for proper development and maintenance of ICC, which has resulted in the widespread acceptance of Kit immunohistochemistry for ICC labelling.16 Despite their central role at the neuromuscular interface and their reliable immunohistochemical detection, structural and/or quantitative alterations in the ICC population have not been reported in MNGIE before. In our patient with prominent gastrointestinal dysmotility, we have demonstrated a complete absence of Kit positive cells in regions where ICC are physiologically vital in the small bowel, e.g. around the myenteric plexus, where Kit immunoreactivity is known to be strongest, in intermuscular septa and within deep muscular plexus. Although ultrastructural data are lacking in our case, disruption of the ICC network appeared to occur without gross structural abnormalities within the bowel wall at the light microscopic level in contrast to previously published studies, reporting e.g. atrophy of the external layer of the muscularis propria and mitochondrial abnormalities in intestinal ganglia cells11,13. However, reducing the complex mechanisms controlling gut motor activity to a single cell type is troublesome and might not be eligible. In the same direction, the question of the representative nature of our findings obtained from a single site of the small bowel has to be critically addressed. In light of the radiologically observed structural abnormalities, complete extrapolation of our results to the whole small bowel may not be adequate. Small bowel manometry, which was not entertained in our patient, might as an in vivo motility study have been helpful to better characterize the pattern of motility disturbance, and possibly might have been suited to provide further clues as to whether rather neuropathic and/or myopathic mechanisms have prevailed in our patient. Notwithstanding these limitations, our findings are novel and might attribute an important pathogenetic role to ICC in MNGIE-related gut dysmotility. In view of the inherent plasticity of ICCs dependent on continuous Kit signalling, it remains unclear whether absence of ICC in MNGIE is due to primary cell death or possibly phenotypic change, i.e. transdifferentiation into a smooth muscle phenotype,17 under the influence of environmental factors specifically related to MNGIE. For example, energy homeostasis in ICC, as a highly specialized cell type, has not been systematically investigated so far, and might on a speculative basis account for ICC loss through mitochondriopathy-related energetic failure.

In summary, we have provided a first description of structural alterations in the ICC network without significant myopathic and/or neuropathic changes in MNGIE. Under this perspective, defective ICC function might be an early step in the pathogenesis of MNGIE-associated gastrointestinal dysmotility, presumably resulting in disturbed electrical pacemaker activity, and negative interference with neurotransmitter modulation, with potentially deleterious effects on intestinal motor output. However, considering the phenotypic variability and complex nature of MNGIE on the one hand and the well-recognized plasticity of ICCs on the other, our results have to be taken cautiously, and further studies are warranted to clarify the pathogenetic role of the ICC network in this rare disease.

Footnotes

Financial disclosures and possible conflicts of interest none.

REFERENCES

- 1.Hirano M, Silvestri G, Blake DM et al. Mitochondrial neurogastrointestinal encephalomyopathy (MNGIE): clinical, biochemical, and genetic features of an autosomal recessive mitochondrial disorder. Neurology 1994; 44: 721–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nishino I, Spinazzola A, Hirano M. Thymidine phosphorylase gene mutations in MNGIE, a human mitochondrial disorder. Science 1999; 283: 689–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Spinazzola A, Marti R, Nishino I et al. Altered thymidine metabolism due to defects of thymidine phosphorylase. J Biol Chem 2002; 277: 4128–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nishigaki Y, Marti R, Copeland WC et al. Site-specific somatic mitochondrial DNA point mutations in patients with thymidine phosphorylase deficiency. J Clin Invest 2003; 111:1913–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sanders KM, Koh SD, Ward SM. Interstitial cells of Cajal as pacemakers in the gastrointestinal tract. Annu Rev Physiol 2006; 68: 307–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Streutker CJ, Huizinga JD, Campbell F et al. Loss of CD117 (c-kit)- and CD34-positive ICC and associated CD34-positive fibroblasts defines a subpopulation of chronic intestinal pseudo-obstruction. Am J Surg Pathol 2003; 27: 228–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jain D, Moussa K, Tandon M et al. Role of interstitial cells of Cajal in motility disorders of the bowel. Am J Gastroenterol 2003; 98: 618–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Isozaki K, Hirota S, Miyagawa J et al. Deficiency of c-kit+ cells in patients with a myopathic form of chronic idiopathic intestinal pseudo-obstruction. Am J Gastroenterol 1997; 92: 332–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Finsterer J, Shorny S, Capek J et al. Lactate stress test in the diagnosis of mitochondrial myopathy. J Neurol Sci 1998; 159: 176–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Marti R, Spinazzola A, Tadesse S et al. Definitive diagnosis of mitochondrial neurogastrointestinal encephalomyopathy by biochemical assays. Clin Chem 2004; 50: 120–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Giordano C, Sebastiani M, Plazzi G et al. Mitochondrial neurogastrointestinal encephalomyopathy: evidence of mitochondrial DNA depletion in the small intestine. Gastroenterology 2006; 130: 893–901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mueller LA, Camilleri M, Emslie-Smith AM. Mitochondrial neurogastrointestinal encephalomyopathy: manometric and diagnostic features. Gastroenterology 1999; 116: 959–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Perez-Atayde AR, Fox V, Teitelbaum JE et al. Mitochondrial neurogastrointestinal encephalomyopathy: diagnosis by rectal biopsy. Am J Surg Pathol 1998; 22: 1141–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Torihashi S, Ward SM, Sanders KM. Development of c-Kit-positive cells and the onset of electrical rhythmicity in murine small intestine. Gastroenterology 1997; 112: 144–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sanders KM. Organization of intestinal pacemakers. Gastroenterology 2001; 120: 319–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ward SM, Burns AJ, Torihashi S, Sanders KM. Mutation of the protoconcogene c-kit blocks development of interstitial cells and electrical rhythmicity in murine intestine. J Physiol 1994; 480: 91–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Torihashi S, Nishi K, Tokutomi Y et al. Blockade of kit signaling induces transdifferentiation of interstitial cells of Cajal to a smooth muscle phenotype. Gastroenterology 1999; 117: 140–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]