Abstract

Objectives:

This study sought to compare the estimation of central systolic blood pressure obtained by two different non-invasive devices, in addition to its comparisons to measured peripheral systolic blood pressure, in a biracial (black/white) community-based cohort.

Methods:

Estimations of central systolic blood pressure by applanation tonometry were obtained in 586 participants of the Bogalusa Heart Study (mean age 43.5 years; 69% white, 54% female), employing 2 different commonly used instruments: Omron HEM-9000AI and Sphygmocor CPV. Peripheral systolic blood pressure was measured using a standard auscultatory technique.

Results:

The estimation of central systolic blood pressure by the Omron device was higher than that of the Sphygmocor device (124.2 +/− 17.1mmHg vs 111.4 +/− 15.2mmHg, p<0.001). Moreover, central systolic blood pressure by Omron was significantly higher than peripheral blood pressure (124.2 +/− 17.1mmgHg vs 119.4 +/− 15.6mmHg, p<0.001); whereas central systolic blood pressure by Sphygmocor was significantly lower than peripheral systolic blood pressure (111.4 +/− 15.2mmHg vs 119.4 +/− 15.6mmHg, p<0.001). Similar results were observed in race and sex-specific analyses.

Conclusion:

These findings support the hypothesis that notable differences exist in the estimation of central systolic blood pressure provided by the instruments utilized in this study. Further standardization studies are required to establish the most appropriate non-invasive estimation of central systolic blood pressure before this parameter may be considered in the assessment, prediction and prevention of cardio-metabolic risk and overt cardiovascular disease in clinical practice.

Keywords: Systolic blood pressure, Central blood pressure, Hypertension, CV risk, Arterial Stiffness, Central Systolic Blood Pressure

INTRODUCTION

The hypothesis that central systolic blood pressure (cSBP) is a better marker of risk for development of cardiovascular disease (CVD) complications seems well founded in that cSBP more accurately represents loading conditions on ventricular muscle, as well as on coronary and cerebral blood vessels1–3. Since it is not practical, for clinical purposes, to measure cSBP invasively, devices have been developed to estimate cSBP from measurements of radial arterial pressure waveforms. Estimation of the central pressure becomes potentially problematic when different methodologies and algorithms are used for its calculation4–6. Available instruments utilize mainly measured peripheral systolic blood pressure (pSBP) —as measured in the brachial artery— and arterial waveforms obtained by applanation tonometry of the radial artery7. cSBP is then calculated by performing regression analysis or utilizing a proprietary transfer function6,8.

Two commonly used instruments for computation of cSBP are the Omron HEM-9000AI (Omron) and the SphygmoCor CPV (Sphygmocor). Both instruments have been compared to invasive arterial measurements of central pressure and significant differences have been reported between the devices and invasive measurements, as well as between the instruments9,10.Despite the growing popularity of non-invasive central blood pressure measurements, little comparison of data obtained from different instruments has been reported for large numbers of subjects.

We aimed to compare cSBP readings computed by the Omron and Sphygmocor devices, as well as its comparisons to pSBP assessed by standard sphygmomanometry, in a biracial (white/black) community-based cohort. The Bogalusa Heart Study (BHS) has been ongoing since 1973, and is a landmark study responsible for recording numerous cardio-metabolic risk factors over time in a community from rural Lousiana, and provided a unique opportunity to conduct these analyses. We reasoned that, for widespread clinical application, the two devices should provide similar estimation of cSBP

METHODS

Study Cohort

The Bogalusa Heart Study is a biracial (65% white and 35% black) long-term study of the early natural history of cardiovascular disease founded by Dr. Gerald S. Berenson in 1973. It involves serial observations from child- to adulthood in subjects living in the semi-rural community of Bogalusa, Louisiana11. For analytical purposes, we considered cross-sectional data from 586 subjects that participated in the Bogalusa Heart Study from March 2007 to June 2010, including 407 white and 320 female participants with available non-invasive measures of central and peripheral blood pressure. Participants were excluded if any relevant screening data were missing or if receiving any antihypertensive medications. All participants in this study gave informed consent for examination. Study protocols were approved by the Institutional Review Board of Tulane University Health Sciences Center.

Hemodynamic Parameters

Two devices were used to obtain central blood pressure data at the same visit via applanation tonometry: Omron HEM-9000AI (Omron Healthcare Co., Ltd., Kyoto, Japan), and SphygmoCor CPV (AtCor Medical, Sydney, Australia). These devices utilize a noninvasive method designed to closely simulate invasive arterial pressures in the aortic arch, involving mathematical algorithms (transfer functions) that process the radial pressure wave to estimate cSBP. Both transfer functions are proprietary. Participants were examined in a sitting position. Each participant underwent 4 radial artery pressure waveform recordings using the Omron and SphygmoCor devices. The mean of each instruments’ recordings was employed for the analyses. Due to known operational difficulties with obtaining pulse wave analytics via the SphygmoCor device12, only those recordings with an operator index >80 (resulting in an average of approximately 3 per participant) were considered for the analyses, following the manufacturer’s recommendations for optimal results.

pSBP measurements were obtained using mercury sphygmomanometers. Participants were also examined in a sitting position with measurements performed by two randomly assigned nurses with three replicates. The first and fifth Korotkoff phases were used to determine systolic and diastolic BP, respectively.13

The arm side utilized for all blood pressure recordings was alternated between subjects; however, the recording arm was consistent for each subject throughout the study.

Laboratory Analysis

Participants were instructed to fast for 12 hours before examination, and compliance with fasting was determined by an interview on the morning of examination. Serum lipoprotein cholesterols and triglycerides were analyzed by using a combination of heparin–calcium precipitation and agar–agarose gel electrophoresis procedures on the Hitachi 902 Automatic Analyzer (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN). Plasma glucose levels were measured as part of a multiple chemistry profile (SMA20; Laboratory Corporation of America, Burlington, NC) by a glucose oxidase method. The laboratory is monitored for precision and accuracy by the Lipid Standardization Program of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, GA.

Statistical Analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using SAS version 9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). Descriptive statistics were calculated for each parameter, and expressed as mean +/− standard deviation (SD) for continuous variables (unless otherwise indicated), and frequency (percent) for categorical variables. Paired-samples t-tests were used to assess mean differences in continuous cSBP parameters obtained by the Omron and Sphygmocor devices for the same individual (within-individual comparisons). Independent samples t-tests were used to assess between groups differences in continuous study variables, and the chi-square test for categorical variables. Normality of distribution was assessed by the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. All analyses were performed on transformed data where appropriate. Correlation coefficients between cSBP by Omron and Sphygmocor were calculated by partial correlation. All p-values are two-tailed.

RESULTS

Participants’ general characteristics by sex are shown in Table 1. There were no statistical differences in males versus females for age. Females had greater HDL-C (p<0.001), while having lower LDL-C (p=0.03) and triglycerides (p<0.001), compared to males. No statistical differences were observed in BMI, or in the percentage of males versus females who smoked or had diabetes.

Table 1:

General study variables by sex group

| Sex |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Male (n=266) | Female (n=320) | p for sex comparison | |

| Age (years) | 43.7 (4.5) | 43.2 (4.6) | NS |

| Race (Whites, n, %) | 193 (72.6) | 214 (66.9) | NS |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 30.6 (6.4) | 30.5 (7.0) | NS |

| TC (mg/dl) | 195.7 (42.0) | 188.4 (41.5) | NS |

| LDL-C (mg/dl) | 132.2 (36.7) | 121.4 (37.4) | 0.03 |

| HDL-C (mg/dl)† | 41.9 (14.5) | 50.6 (13.5) | <0.001 |

| Triglycerides (mg/dl)† | 131 (105) | 106 (100) | <0.001 |

| Glucose (mg/dl)† | 91.0 (14) | 91.5 (18) | NS |

| Smoking (n, %) | 71 (26.7%) | 94 (29.4%) | NS |

| Diabetes (n, %) | 27 (10.2%) | 25 (7.8%) | NS |

Values considered as median and interquartile range.

BMI, body mass index; TC, Total Cholesterol; LDL-C, Low Density Lipoprotein-Cholesterol; HDL-C, High Density Lipoprotein Cholesterol

Table 2 depicts characteristics of the hemodynamic variables, by sex and by race. Males (versus females) and blacks (versus whites) showed significantly greater pSBP, pDBP and cSBP Sphygmocor (p<0.01). Interestingly, cSBP Omron was higher in blacks versus whites (p<0.01), but no significant differences by sex were observed.

Table 2:

Hemodynamic study variables by sex group

| Sex |

Race |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male (n=266) | Female (n=320) | White (n=407) | Black (n=179) | p for comparison | |

| pSBP | 122.2 (15.1) | 115.8 (15.3) | 115.4 (11.9) | 126.2 (19.7) | <0.01 S,R |

| pDBP | 85.3 (9.9) | 80.2 (8.8) | 80.8 (7.9) | 86.2 (11.9) | <0.01 S,R |

| cSBP Omron | 124.4 (16.3) | 123.9 (17.7) | 121 (13.8) | 131.3 (21.2) | NS S, <0.01 R |

| cSBP Sphygmocor | 113.9 (15.6) | 109.4 (14.6) | 108.6 (12.7) | 117.7 (18.2) | <0.01 S,R |

pSBP, peripheral systolic blood pressure (auscultatory); pDBP, peripheral diastolic blood pressure (auscultatory); cSBP Omron, central systolic blood pressure obtained by the Omron HEM 9000 AI instrument; cSBP Sphygmocor, central systolic blood pressure obtained by the Sphygmocor CPV instrument.

Sex comparison (Male vs Female)

Race comparison (White vs Black)

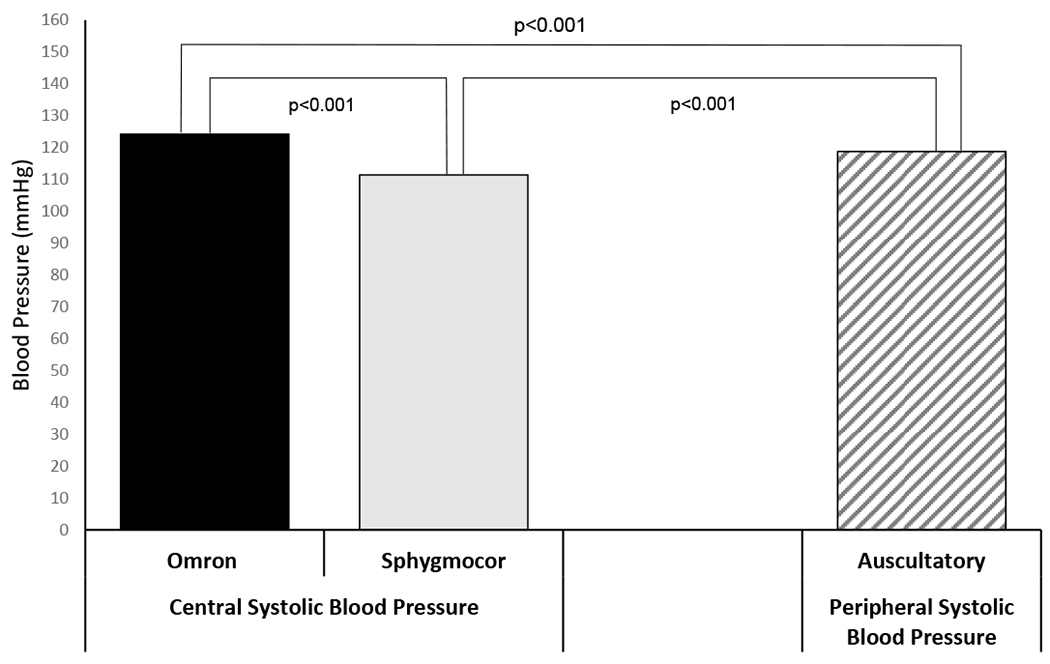

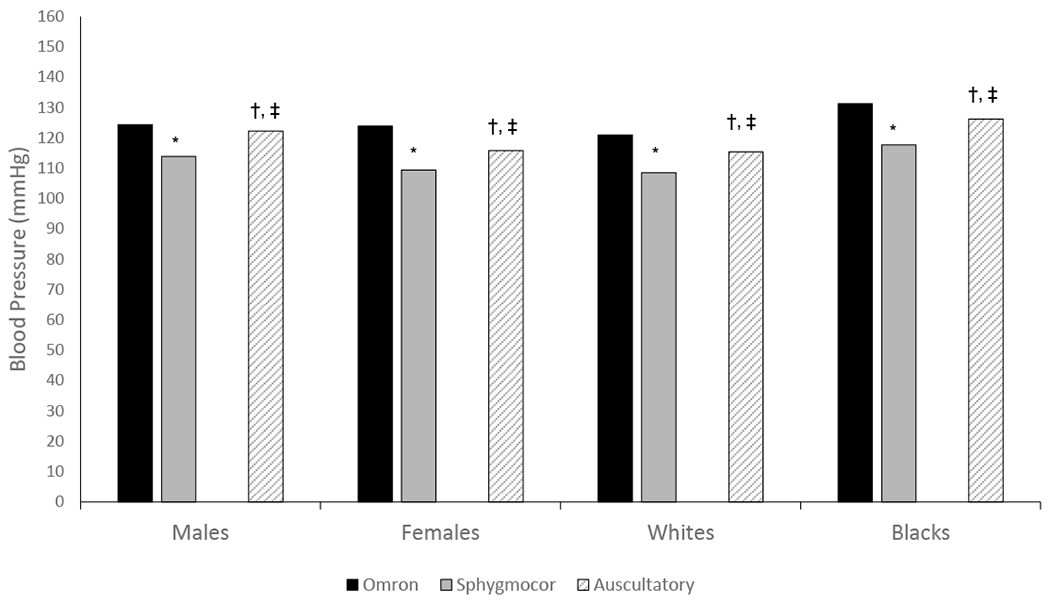

In general, participants showed significantly greater cSBP estimated by the Omron device compared to the SphygmoCor device (124.2 ±17.1 mmHg vs. 111.4±15.2 mmHg, p<0.001) (Figure 1). Furthermore, cSBP estimated by the Omron device was significantly higher than pSBP (124.2 +/− 17.1mmHg vs 119.4 +/− 15.6mmHg, p<0.001); whereas cSBP estimated by the Sphygmocor device was significantly lower than pSBP (111.4 +/− 15.2mmHg vs 119.4 +/− 15.6mmgHg, p<0.01). These results were consistently observed across all race and sex group (Figure 2)

Figure 1:

Mean comparisons of central systolic blood pressure (Omron vs. SphygmoCor) and peripheral systolic blood pressure (auscultatory)

Figure 2:

Race- and Sex- specific mean comparisons of central systolic blood pressure (Omron vs. SphygmoCor) and peripheral systolic blood pressure (auscultatory)

*, comparison between cSBP Omron and cSBP Sphygmocor (p<0.001)

†, comparison between cSBP Omron and pSBP Auscultatory (p<0.001)

‡, comparison between cSBP Sphygmocor and pSBP Auscultatory (p<0.001)

cSBP, central systolic blood pressure; pSBP, peripheral systolic blood pressure

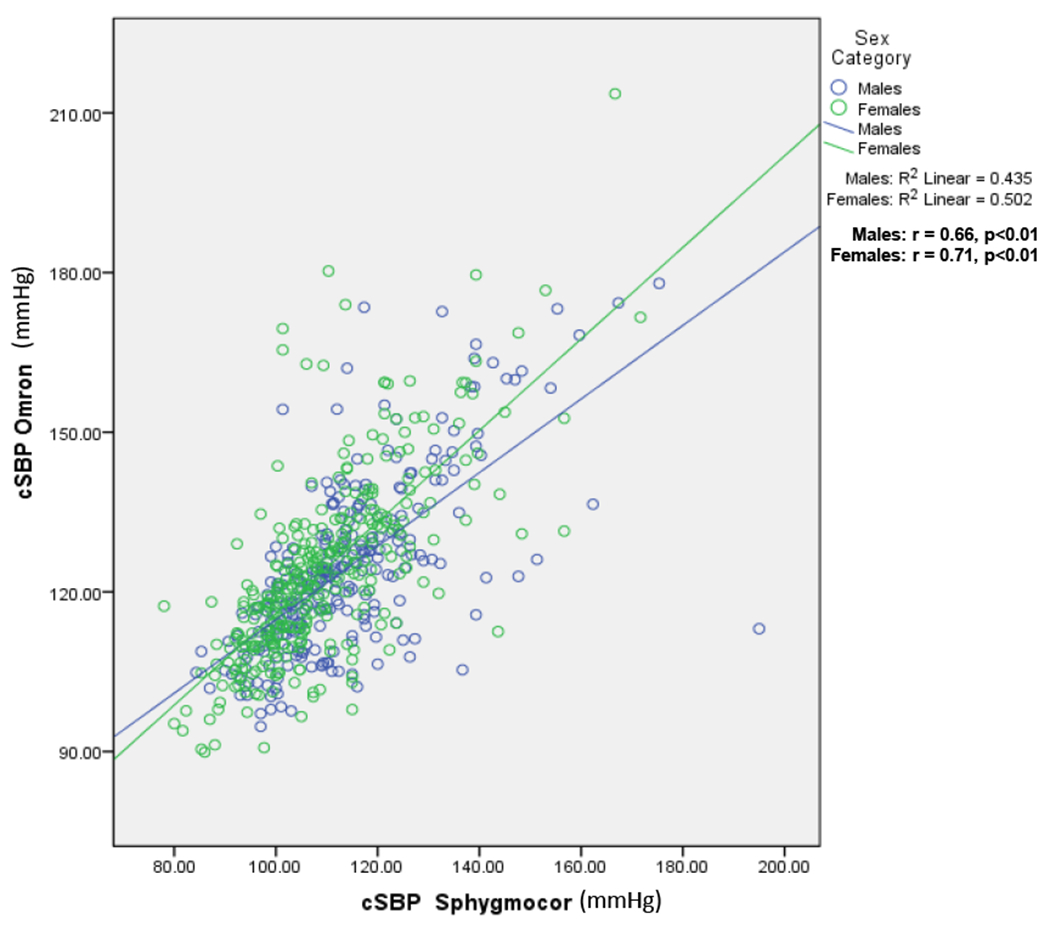

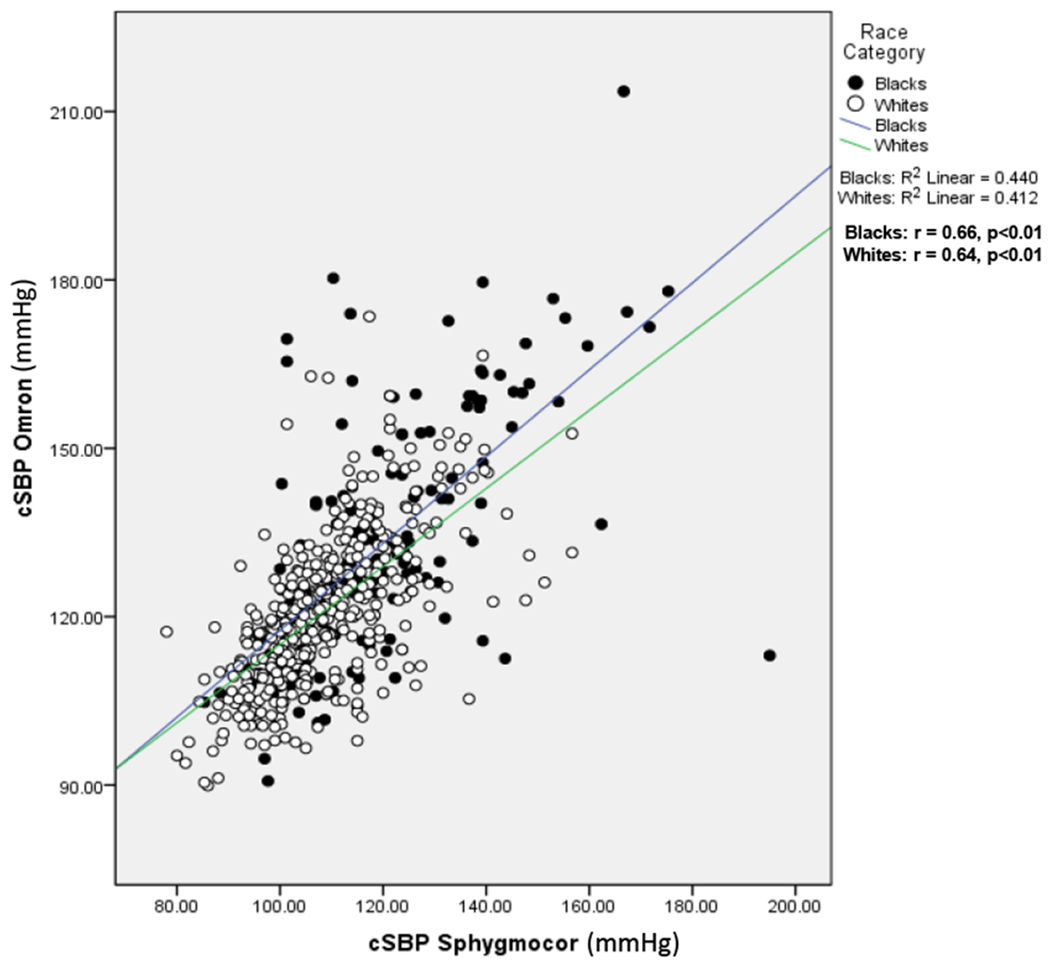

The correlations of cSBP between the Omron and SphygmoCor devices by sex and race are shown in Figures 3 and 4, respectively. cSBP by Omron is strongly correlated with cSBP by Sphygmocor in males (r=0.66, p<0.01), females (r=0.71, p<0.01), blacks (r=0.66, p<0.01) and whites (r=0.64, p<0.01).

Figure 3:

Correlation of cSBP by Omron and Sphygmocor by sex group.

r, correlation coefficient; R2, coefficient of determination

cSBP Omron, central systolic blood pressure obtained by the Omron HEM 9000 AI instrument; cSBP Sphygmocor, central systolic blood pressure obtained by the Sphygmocor CPV instrument.

Figure 4:

Correlation of cSBP by Omron and Sphygmocor by race group.

r, correlation coefficient; R2, coefficient of determination

cSBP Omron, central systolic blood pressure obtained by the Omron HEM 9000 AI instrument; cSBP Sphygmocor, central systolic blood pressure obtained by the Sphygmocor CPV instrument.

DISCUSSION

The concept of cSBP is easy to grasp for the clinician. Thus, it is understandable why the non-invasive estimation of cSBP has attracted so much attention to device manufacturers. However, as demonstrated by data from this study, the values obtained for cSBP depend on the device employed to compute this measure.

Assuming invasive catheterization as a gold standard for measuring cSBP, a comparison made between the SphygmoCor and Omron devices with data obtained from invasive measurements found low correlation levels for SphgymoCor (r = 0.11, p = 0.56) and Omron (r = 0.15, p = 0.41) with the invasive catheter 14 . In our analyses, we found significant differences when comparing cSBP —estimated by the two devices— with recordings of peripheral systolic blood pressure measured by mercury sphygmomanometer (Fig 1)

Estimated cSBPs, as recorded by Omron and SphgymoCor, also differed. The Omron device estimated a significantly greater cSBP (124.2±17.1 mmHg) relative to the SphgymoCor device (111.4±15.2 mmHg) —average mean difference 11.8 mmHg, p<0.001 (Fig 1). These observations raise serious concerns regarding the accuracy of using applanation tonometry-derived cSBP [by multiple devices] to estimate the risk of future cardiovascular events, and potentially direct therapy. In addition, this difference in data recorded from multiple devices could have major implications in diagnosing and treating pre-hypertension and stage 1 hypertension.

It has been suggested by some authors that central pressures may be used clinically because of the existing strong correlation between pSBP and cSBP, regardless of the device used to estimate the latter6,15. Nevertheless, as shown by our data, correlation does not necessarily confer accuracy or validity. A follow-up study of both the SpygmoCor and Omron devices compared data obtained from 143 rural black South Africans. Similar to previous studies, a strong correlation but substantially higher, cSBP (18.8 mmHg) for Omron devices over SphygmoCor devices was found.16

Our current study does not provide an explanation for the absolute value difference in cSBP recorded by the Omron and SphygmoCor devices. It does, nonetheless, underscores interesting information in connection with these differences, as they remain consistent in spite of race (white vs. black) or sex. Similar to a recent report by our group17, our current study shows the difference between cSBP and pSBP is greater for females than for males for the Omron device. Of note, the opposite was observed for the Sphygmocor device. Significant differences between cSBP (by the two instruments) and pSBP were also observed in race-specific (whites vs. blacks) analyses, as depicted in figure 2.

A probable explanation for the differences in estimated cSBP between the Sphygmocor and Omron devices is in the measurements and extrapolation of the second late systolic shoulder peak (pSBP2)18,19. A considerable difference between cSBP estimates of Omron HEM-9000 AI and SphygmoCor was found to be due to algorithm differences20. This hypothesis was elegantly tested when Omron-measured curves were input into the SphygmoCor software16, thereby changing the estimation of cSBP.

Our findings suggest that the incorporation of non-invasive measurements of central blood pressure into clinical practice has not yet matured. For this to occur, there must be at least a detailed revision on how data recorded from applanation tonometry-based devices are used in estimating central hemodynamics. Our current findings, and others21–23 suggest that sex-, race- and age-specific should be considered as important parameters in the development of future standards in the estimation of central hemodynamics —such as cSBP.

Acknowledgments

Sources of Funding:

This study was supported by grant AG-041200 from the National Institute on Aging and ES-021724 from National Institute of Environmental Health Science.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest / Disclosures:

Authors have no potential conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Sharman JE, Laurent S. Central blood pressure in the management of hypertension: soon reaching the goal? J Hum Hypertens. 2013;27:405–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cho SW, Kim BK, Kim JH, Byun YS, Goh CW, Rhee KJ, Ahn HS, Lee BK, Kim BO. Non-invasively measured aortic wave reflection and pulse pressure amplification are related to the severity of coronary artery disease. J Cardiol. 2013;62:131–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Roman MJ, Devereux RB, Kizer JR, Lee ET, Galloway JM, Ali T, Umans JG, Howard BV. Central pressure more strongly relates to vascular disease and outcome than does brachial pressure: the Strong Heart Study. Hypertension. 2007;50:197–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gallagher D, Adji A, O’Rourke MF. Validation of the transfer function technique for generating central from peripheral upper limb pressure waveform. Am J Hypertens. 2004;17:1059–1067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Salvi P Is validation of non-invasive hemodynamic measurement devices actually required? Hypertens Res. 2013;37:7–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wohlfahrt P, Krajcoviechová A, Seidlerová J, Mayer O, Filipovsky J, Cífková R. Comparison of noninvasive assessments of central blood pressure using general transfer function and late systolic shoulder of the radial pressure wave. Am J Hypertens. 2014;27:162–168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Takazawa K, Kobayashi H, Shindo N, Tanaka N, Yamashina A. Relationship between radial and central arterial pulse wave and evaluation of central aortic pressure using the radial arterial pulse wave. Hypertens Res. 2007;30:219–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen C-H, Nevo E, Fetics B, Pak PH, Yin FCP, Maughan WL, Kass DA. Estimation of Central Aortic Pressure Waveform by Mathematical Transformation of Radial Tonometry Pressure : Validation of Generalized Transfer Function. Circulation. 1997;95:1827–1836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ding F-H, Fan W-X, Zhang R-Y, Zhang Q, Li Y, Wang J-G. Validation of the noninvasive assessment of central blood pressure by the SphygmoCor and Omron devices against the invasive catheter measurement. Am J Hypertens. 2011;24:1306–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Papaioannou TG, Protogerou AD, Stamatelopoulos KS, Vavuranakis M, Stefanadis C. Non-invasive methods and techniques for central blood pressure estimation: procedures, validation, reproducibility and limitations. Curr Pharm Des. 2009;15:245–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Berenson GS, McMahan CA, Voors AW, Webber LS, Srinivasan SR F GC, Foster TABC. Cardiovascular Risk Factors in Children—The Early Natural History of Atherosclerosis and Essential Hypertension. 1st ed. New York: Oxford University Press; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Calabia J, Torguet P, Garcia M, Garcia I, Martin N, Guasch B, Faur D, Vallés M. Doppler ultrasound in the measurement of pulse wave velocity: agreement with the Complior method. Cardiovasc Ultrasound. 2011;9:1–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pickering TG, Hall JE, Appel LJ, Falkner BE, Graves J, Hill MN, Jones DW, Kurtz T, Sheps SG, Roccella EJ. Recommendations for blood pressure measurement in humans and experimental animals: Part 1: blood pressure measurement in humans: a statement for professionals from the Subcommittee of Professional and Public Education of the American Heart Association Cou. Hypertension. 2005;45:142–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ding F-H, Li Y, Zhang R-Y, Zhang Q, Wang J-G. Comparison of the SphygmoCor and Omron devices in the estimation of pressure amplification against the invasive catheter measurement. J Hypertens. 2013;31:86–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hirata K, Kojima I, Momomura S. Noninvasive estimation of central blood pressure and the augmentation index in the seated position: a validation study of two commercially available methods. J Hypertens. 2013;31:508–15; discussion 515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kips JG, Schutte AE, Vermeersch SJ, Huisman HW, Van Rooyen JM, Glyn MC, Fourie CM, Malan L, Schutte R, Van Bortel LM, Segers P. Comparison of central pressure estimates obtained from SphygmoCor, Omron HEM-9000AI and carotid applanation tonometry. J Hypertens. 2011;29:1115–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chester R, Sander G, Fernandez C, Chen W, Berenson G, Giles T. Women have significantly greater difference between central and peripheral arterial pressure compared with men: the Bogalusa Heart Study. J Am Soc Hypertens. 7:379–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pauca AL, Kon ND, O’Rourke MF. The second peak of the radial artery pressure wave represents aortic systolic pressure in hypertensive and elderly patients. Br J Anaesth. 2004;92:651–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.O’Rourke MF, Pauca AL. Augmentation of the aortic and central arterial pressure waveform. Blood Press Monit. 2004;9:179–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rezai M-R, Goudot G, Winters C, Finn JD, Wu FC, Cruickshank JK. Calibration mode influences central blood pressure differences between SphygmoCor and two newer devices, the Arteriograph and Omron HEM-9000. Hypertens Res. 2011;34:1046–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mitchell GF, Parise H, Benjamin EJ, Larson MG, Keyes MJ, Vita JA, Vasan RS, Levy D. Changes in arterial stiffness and wave reflection with advancing age in healthy men and women: the Framingham Heart Study. Hypertension. 2004;43:1239–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gatzka CD, Kingwell BA, Cameron JD, Berry KL, Liang YL, Dewar EM, Reid CM, Jennings GL, Dart AM. Gender differences in the timing of arterial wave reflection beyond differences in body height. J Hypertens. 2001;19:2197–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Narayan O, Casan J, Szarski M, Dart AM, Meredith IT, Cameron JD. Estimation of central aortic blood pressure: a systematic meta-analysis of available techniques. J Hypertens. 2014;32:1727–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]