Abstract

Fabricating nanostructures and doping engineering are beneficial to tailor the photocatalytic activity of semiconductor materials, and the semiconducting photocatalysis is deemed to be one of the potential protocols to handle the environmental pollution and energy crisis issues. Herein, rodlike Cd-doped ZnWO4 Zn1–xCdxWO4 nanoarchitectures were triumphantly prepared by a template-free strategy. The crystal structure, chemical state, optical, and photocatalytic features of the Zn1–xCdxWO4 nanoarchitectures were studied using a variety of characterizations. The Zn1–xCdxWO4 nanoarchitectures exhibit glorious photocatalytic performance compared with pristine ZnWO4 for the degradation of methyl orange in sewage. Mechanistic studies were executed for getting insights into the photocatalytic degradation process, and the remarkable photocatalytic property of the doped ZnWO4 nanoarchitectures is attributed to the boosted optical absorptive efficiency and the valid segregation and transmission of photogenerated charge carriers deriving from doping effects. The doped nanoarchitectures of this work have promising applications in the territories such as environment and energy chemistry, and the insight proposed in this work will contribute to develop other functionalized nanoarchitectures.

1. Introduction

Environmental pollution, especially industrial wastewater, has drawn public attention because of the growing threat to human safety.1 Now, how to solve the energy conversion and environmental pollution problem has become more and more urgent.2 Photocatalytic technology has been employed to environmental pollution control and efficient energy conversion (light energy to chemical energy, especially industrial wastewater treatment), which is considered to be sustainability and environmentally friendly.3 Therefore, utilization of photocatalytic technology for the remediation of environmental pollutants has been received extensive interests in recent years.

Abundant semiconductors with photocatalytic activity have recently attracted the attention of researchers because of the potential applications in the renovation of environmental pollution.4 Those amazing photocatalysts include TiO2 (3.3 eV),5 ZnO (3.4 eV),6 ZnS (3.7 eV),7 ZnWO4 (3.7 eV),8 CdS (2.4 eV),9 α-FeOOH (2.6 eV),10 and so on. Among these semiconductors, ZnWO4 with a wolframite structure,11 is one of the most potential and splendid photocatalysts, and it is regarded as a reliable substitute for TiO2 and ZnO because of the suitable band gap energy (3.7 eV) as well as the high catalytic activity, chemical stability, nontoxic, and low-cost. The common researches on semiconductor photocatalyst of ZnWO4 mainly include the following aspects: the researches about changing the photocatalytic activity of ZnWO4 by controlling its morphology, such as rod,12 hollow,13 mesoporous,14 and core–shell15 structures have been deeply studied. Because the optimization of photocatalytic performance was discovered, ZnWO4 as a substitute for the TiO2 and ZnO has been extensively researched on how to apply in the disposal of water pollution, detoxication of heavy metal,16 and dispose of other solids and gases pollutants. The way of controlling the morphology were rarely used in the industrial production, until now, which is probably because a good deal of photo-generated carriers are excited, which irregularly generate taunt the recombination of carriers and further impose restrictions on photocatalytic performance.17 Composite photocatalysts about ZnWO4 by means of constructing heterostructures have been reported, for instance, CdS/Zn1–xCdxWO4,18 BiOI/ZnWO4,19 LAS/ZnO/ZnWO4.20 Benefiting from heterostructure effects, admirable visible-light photocatalytic property of these composited materials can be achieved. Compared with changing the photocatalytic property of ZnWO4 via adjusting its morphology, the photocatalytic activity of the ZnWO4-based heterostructure has been obviously improved. However, that the quantity production has not still reached the expected value is one of the significant factors to limit its application of industrial production.21 Up to now, some semiconductor materials about ion-doped ZnWO4 have been successfully prepared, such as F:ZnWO4,22 Cd:ZnWO4,23 and B:ZnWO4.24 Although the doped ZnWO4 materials have been successfully synthesized, in-depth studies on the photocatalytic mechanism of the doped ZnWO4 are still limited.25 Furthermore, as an element of the same family of zinc, cadmium has been rarely incorporated into zinc tungstate nanoarchitectures, and the crystal structure properties caused by the introduction of cadmium remain limited.

In this work, rod-like Cd-doped ZnWO4 (Zn1–xCdxWO4) nanoarchitectures were fabricated by a template-free strategy. The crystal structure, chemical state, optical, and photocatalytic features of the Zn1–xCdxWO4 nanoarchitectures were studied in detail. The doped ZnWO4 nanoarchitectures display more efficient photocatalytic performance than that of pristine ZnWO4 for degrading methyl orange (MO) in sewage. In light of the experimental results, the photocatalytic process and the boosted photocatalytic mechanism were proposed.

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Morphology and Structure

The phase and crystal structure of as-prepared Zn1–xCdxWO4 samples were explored through X-ray diffraction (XRD). The XRD patterns of Zn1–xCdxWO4 solids are shown in the Figure 1, which is in accordance with that of ZnWO4 (JCPDS no. 15-0774) and no diffraction peaks for cadmium species are found in the Cd-doped ZnWO4 materials. This situation possibly is because the synthesized samples are of high purity. The diffraction peaks of Zn1–xCdxWO4 are mainly located at 15.5, 18.7, 23.8, 24.5, 31.5, 36.3, 38.1, 41.2, 44.3, 50.1, 53.7, 61.7, and 64.9°, which is corresponded to (010), (100), (011), (110), (111), (021), (200), (121), (112), (220), (202), (113), and (132) crystal faces of ZnWO4. But one phenomenon is that with the increase of the doping amount, the diffraction peak intensity presents a slight enhancement, such as (021) and (202) crystal faces. It is clearly that Cd element has substituted some zinc atoms in the ZnWO4 lattice because the Zn1–xCdxWO4 and pristine ZnWO4 show similar lattice parameters.26 This impact is given the credit that the ion-doping facilitates the process of crystallization, which caused rearrangement of lattice ordering in the ZnWO4. According to the literature of Huang and Ye,27 XWO4 (X is on behalf of Zn and Cd) is a part of a typical ABX4 structure and monoclinic crystallization (Figure 2). This XWO4 (X represents Zn and Cd) structure also belongs to the wolframite structure, which is identified as a distorted hexagonal structure that is a sealed packing of Ο atoms with X (Zn or Cd) and W ions. Thereinto, six O atoms surround the focus of W atom and merely two O atoms have different bond distances. As is shown in the Figure 2a, A (Zn or Cd) and W atoms occupy one-fourth of the octahedral voids. This distorted octahedrons of XWO4 includes only one type of cations, which develops limitless zig-zag chains stretching on the c axis. As is shown in the Figure 2b,c, the structure of Zn1–xCdxWO4 is less than two octahedra structures. ZnWO4 and CdWO4 can be concatenated by edges (Figure 2b), when the octahedron is identical. Compared with the same octahedra structure, ZnWO4 and CdWO4 are joined by corners (Figure 2c). As a consequence, the wolframite structure of ZnWO4 and CdWO4 can contribute to formulate the Zn1–xCdxWO4 nanorods as well as regulate its crystallinity and control the particle size.

Figure 1.

XRD patterns of ZnWO4 and Zn1–xCdxWO4.

Figure 2.

Wolframite structures of (a) ZnWO4, (b) Zn1–xCdxWO4, and (c) Zn1–xCdxWO4.

Hence, Cd atoms are easily doped into the ZnWO4 lattice, benefiting from that the CdWO4 and ZnWO4 have the similar wolframite structure. The augment of the diffraction peak intensity is due to that Cd-doped ZnWO4 induces broadening of full width at half maxima. Furthermore, for investigating the change in crystallinity, we estimated the relative crystallinities of the samples. The values of relative crystallinity are found to be 61.43% (ZnWO4), 58.89% (Zn0.98Cd0.02WO4), 51.22% (Zn0.96Cd0.04WO4), 47.72% (Zn0.94Cd0.06WO4), 31.55%, respectively. Beyond that, the crystallite sizes of Zn1–xCdxWO4 solids were estimated by the Scherrer’s equation, and the crystallite sizes are 21.36 nm (ZnWO4), 16.34 nm (Zn0.98Cd0.02WO4), 15.88 nm (Zn0.96Cd0.04WO4), and 14.58 nm (Zn0.94Cd0.06WO4), respectively, demonstrating the synthesized architectures are in the nanoscale.

The morphology of Zn1–xCdxWO4 architectures were probed by the scanning electron microscopy (SEM). One can well-perceive in the Figure 3, all of the samples show a typical rod-like structure. Compared to the pure ZnWO4 we acquired, the Zn1–xCdxWO4 nanorods stepwise became slender with the augment of the Cd2+ amount, which may be attributed to the lattice distortion of ZnWO4 because the Cd2+ participated in the process of crystal nucleus growth. As shown in the Figure 4a, it is obvious that clubbed ZnWO4 architectures are nonuniform, with an average length of ∼250 nm and a mean radius of ∼15 nm. The morphologies of as-prepared Zn0.98Cd0.02WO4, Zn0.96Cd0.04WO4 and Zn0.94Cd0.06WO4 were shown in the Figure 4b–d. The results clearly show that the Zn1–xCdxWO4 samples shown nanorods contour with average length of 225, 200, 175 nm and a mean radius of 18, 20, 22 nm, respectively. Being reckoned on the geometrical numeration, the consequence is in accord with XRD analyses. That indicates that ions doping are contributed to break the atomic configuration, and ultimately induce alteration of the morphology by a chemical synthesis.

Figure 3.

SEM images of Zn1–xCdxWO4, (a) x = 0, (b) x = 0.02, (c) x = 0.04, and (d) x = 0.06.

Figure 4.

(a) Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) image, (b) high-resolution TEM (HRTEM) image, (c) selected area electron diffraction (SAED) pattern, and (d) energy disperse X-ray (EDX) spectrum of the Zn0.94Cd0.06WO4 architecture.

In order to further survey the microstructure of the Zn0.94Cd0.06WO4 architecture, TEM measurement was implemented. From Figure 4a, the sample displays a typical rod-like structure with an average length of ∼175 nm. The HRTEM image (Figure 4b) of the Zn0.94Cd0.06WO4 nanoarchitecture exhibits distinct lattice fringes with an interplanar distance of 3.37 and 4.42 Å, assigning to the (100) and (110) lattice plane of highly crystalline ZnWO4. The finding correlates well with the SAED pattern, which represents an emblematic single crystal diffraction profile with protruding diffraction points of ZnWO4 lattice planes (Figure 4c). The EDX spectrum (Figure 4d) further show the existence of tungsten, cadmium, zinc, and oxygen in Zn0.94Cd0.06WO4 nanoarchitecture.

The EDX element mapping measurement was performed to evaluate the distribution of different elements of Zn0.94Cd0.06WO4 nanorods. Just as Figure 5a, the sample of Zn0.94Cd0.06WO4 presents a rod-like structure. The colored dots are on behalf of the distribution of the corresponding elements. All of the element distributions are further shown in the Figure 5a–e, respectively. From these pictures, we can confirm that the elements of Cd, Zn, W, and O almost uniformly distributed in the rod-like nanoarchitectures.

Figure 5.

Element mapping images of Zn0.94Cd0.06WO4. (a) SEM image, (b) O mapping, (c) Zn mapping, (d) W mapping, and (e) Cd mapping.

According to Figure 6, the surface chemical states of Zn1–xCdxWO4 nanorods were explored by the XPS analysis. Here, we take Zn0.94Cd0.06WO4 as the representative for analysis. The XPS survey of as-prepared Zn0.94Cd0.06WO4 nanorod displays the following elements, such as Zn, Cd, W, and O, which is in accordance with the feature of our synthesized samples. The C 1s signal is discovered in the Figure 6a, which is due to adventitious hydrocarbon stem from the XPS apparatus. The high resolution XPS spectrum of Zn 2p1 and Zn 2p3 signal is shown in the Figure 6c, the binding energy of those peaks are 1044.63 and 1021.38 eV, which is agreed with Zn2+ in the ZnWO4 architecture. According to Figure 6d, the W 4f lines exhibit two components with binding energies of 35.76 eV (W 4f7/2) and 38.18 eV (W 4f5/2), respectively. The higher binding energy value (38.18 eV) is attributed to the oxidation state of the W6+, while the lower value (36.46 eV) may be assigned to the oxidation state of W5+. The peak of W 4f signal is 38.18 eV in the Figure 6d, and it is consistent with the literature. Furthermore, the O 1s orbit mainly reflects in the following one peak, and the binding energy is 530.13 eV. Two weak Cd peaks are shown on the Figure 6b. In order to further detect the Cd 3d signal, the high resolution XPS spectra of two peaks consistent with the Cd 3d3 and Cd 3d5 are discovered at 412.23 and 405.03 eV in Figure 6b. It indicates that the Cd2+ ions exist in the of Zn0.94Cd0.06WO4. Scilicet, Cd atoms may substitute Zn atoms in the Zn–O and Zn–W frameworks of ZnWO4. It means that some Cd 3d gap states appear on the band gap of ZnWO4 and the prepared Zn1–xCdxWO4 can produce hole (h+) and OH species on the surface.

Figure 6.

X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) profiles of Zn0.96Cd0.04WO4. (a) Survey XPS spectrum, (b) high resolution Cd 3d scan, (c) high resolution Zn 2p scan, (d) high resolution W 4f scan, and (e) high resolution O 1s scan.

2.2. Photocatalytic Performance

In order to thoroughly discuss and analyze the degradation efficiency in the photocatalytic process, MO was selected as a representative of the model pollutant. The results of photocatalytic activity executed under ultraviolet light are shown in the Figure 7. Before the light irradiation, hybrid heterogeneous system has been kept in the dark for 20 min to realize the goal of adsorption and desorption equilibrium in the system of Zn1–xCdxWO4 nanorods and MO solution. From Figure 7a, no matter how many doping amounts of Cd2+, the absorbance of samples is less than 5% in the dark. That is benefited from the similar wolframite structure leading to the approximate adsorption situation. Nevertheless, photocatalytic activity is prominently influenced by Cd-doped ZnWO4 nanorods. The photocatalytic degradation rates of different Cd2+ doping amounts are 62.0% (x = 0), 71.6% (x = 0.02), 79.4% (x = 0.04), and 89.5% (x = 0.06), respectively. For Zn1–xCdxWO4 nanorods, the photocatalytic activities for MO degradation under ultraviolet light comply with the order of ZnWO4 < Zn0.98Cd0.02WO4 < Zn0.96Cd0.04WO4 < Zn0.94Cd0.06WO4. The degradation rate of Zn0.94Cd0.06WO4 is 1.5 times than that of pure ZnWO4. These phenomena uncovers a pivotal role of ion doping in invigorating the photocatalytic activity. To display the novelty, superiority, and advantages of this work, we compared the obtained photocatalytic capabilities of the synthesized materials over the other similar materials reported in the literature. The comparison results are shown in Table S1. From Table S1, we can find that the Zn1–xCdxWO4 samples by the hydrothermal process not only have the excellent photocatalytic performance, but also possess the controlled morphology (just as Figure 3).

Figure 7.

Photocatalytic performance under ultraviolet light irradiation, (a) degradation curves, and (b) first-order kinetic model of Zn1–xCdxWO4.

According to Figure 7b, the degradation of MO with Zn1–xCdxWO4 nanorods were fitted to pseudo-first-order kinetics in ultraviolet light. And the degradation constants (k) of Zn1–xCdxWO4 nanorods are estimated as 0.155 h–1 (ZnWO4), 0.211 h–1 (Zn0.98Cd0.02WO4), 0.277 h–1 (Zn0.96Cd0.04WO4), and 0.347 h–1 (Zn0.94Cd0.06WO4), respectively. The degradation constant of Zn0.94Cd0.06WO4 is 2.24 times higher than that of primitive ZnWO4. Furthermore, the elevant data of kinetic constants of photocatalytic degradation are shown in Table S2. Also, the standard errors of first order kinetic constants are very small, which indicates that the values are consistent with the average value. This once again indicates that Cd doping is a key role to enhance the photocatalytic activity of ZnWO4, which is consisted with that of photocatalytic degradation efficiency. In general, ion doping is regard as one of the most principal element to generate defects because it can disorganize the semiconductor lattice structure. Production of many electron traps is due to Cd atoms interpose in the ZnWO4 nanorods. On the one hand, Cd-doped ZnWO4 nanorods create many electron traps, which is favorable to capture the photoelectrons and improve the life of photogenic carriers.28 Furthermore, Cd2+ doping is conducive to the process of that the formed defects transfer to the surface of the semiconductor material and further raise the yield of the photogenic charge carrier.

To gain further insight into the stability of photocatalytic activity, the multiple cyclic experiments of Zn0.94Cd0.06WO4 nanorod are shown in Figure 8. Although photocatalytic degradation was slightly reduced after four cycles, the final degradation rate still approached 90% under the same reaction conditions. The kinetic constant profile of four run cyclic experiment and elevant data of kinetic constants of photocatalytic degradation (cyclic experiment) are shown in Figure S1 and Table S3, respectively. From Figure S1, the degradation of MO with Zn0.94Cd0.06WO4 nanorods were fitted to pseudo-first-order kinetics in ultraviolet light (four cyclic tests). Besides, the degradation constants (k) of Zn0.94Cd0.06WO4 nanorods were estimated as 0.399 h–1 (1st run), 0.355 h–1 (2nd run), 0.302 h–1 (3rd run), and 0.282 h–1 (4th run), respectively. From Table S3, we may find that the data is in accordance with Figure S1. Also, the standard errors of first order kinetic constants are very small, which is indicated that the fitting values agree with the average value. Furthermore, the structural stability of the Zn0.94Cd0.06WO4 nanorod is studied through the crystal structure of Zn0.94Cd0.06WO4 (before and after cyclic experiment), and the result is shown in Figure 8b. It can be seen from the picture, the XRD diffraction peaks of Zn0.94Cd0.06WO4 (after cycle) agree with standard cards of ZnWO4 (JCPDS no. 15-0774) and no other peaks are discovered.

Figure 8.

(a) Four runs of the photocatalytic cyclic experiment for Zn0.94Cd0.06WO4, and (b) XRD patterns of Zn0.94Cd0.06WO4 before and after cyclic experiments.

2.3. Photoelectric Properties

Light absorption properties studies of the as-made photocatalysts were executed on ultraviolet–visible (UV–vis) diffuse reflectance spectra (DRS). The absorption studies of Zn1–xCdxWO4 nanorods were carried out with the wavelength of 800–200 nm as well as using BaSO4 as a reference. From Figure 9a, the red shift trend of Zn1–xCdxWO4 nanorods gradually increases with the increase of the Cd2+ doping amount. In addition, the band gap energy of all the samples was estimated by using the formula 1

| 1 |

where C is a constant, h is Planck constant, ν is the frequency of the incident photon, α is the absorption coefficient, and the Eg represents the band gap energy of the samples. The detailed data of band gap energy are calculated to be 3.48 eV (ZnWO4), 3.37 eV (Zn0.98Cd0.02WO4), 3.21 eV (Zn0.96Cd0.04WO4), and 3.17 eV (Zn0.94Cd0.06WO4), respectively. The decrease of band gap with the augment of the Cd content dates from the absorption at length wavelengths near visible light. Therefore, it can be seen that light absorption enhancement of Zn1–xCdxWO4 nanorods are benefited from the raised Cd2+ doping amount, which is controlling the change of the energy band structure and the improvement of photon utilization.

Figure 9.

(a) UV–vis DRS and (b) estimated band gap energies for pure ZnWO4 and Zn1–xCdxWO4.

Photoelectrochemical properties of Zn1–xCdxWO4 nanorods are shown in Figure 10, which includes chronoamperometry (IT), electrochemical impedance spectra (EIS) and Mott–Schottky (MS), respectively. The equivalent circuit diagram of this measurement is inserted in the Figure 10b, R1 is on behalf of the resistance of solution, Cd stands for the impedance of the sample and solution, Rct represents the polarization resistance (charge transfer resistance), and the total resistance R represents the sum of R1 and the shunt resistance. The counter electrode of Pt and the reference electrode of saturated calomel are served as these conditions of this empirical study. The other experimental conditions of optoelectronic chemistry remain unification, the electrolyte is 0.1 mol L–1 Na2SO4, and the solution of pH was adjusted to 7.0. The photocurrent intensities of a variety of Zn1–xCdxWO4 nanorods were surveyed by the chronoamperometry (IT) in the Figure 10a. The intensity of the photocurrent gradually increases under ultraviolet radiation because of the increase of Cd2+ dosage. When the doping amount of Cd2+ is up to 0.06, the intensity of the photocurrent of Zn1–xCdxWO4 is 3.5 times greater than that of pristine ZnWO4. By doping the Cd2+, the separation of photogenerated carriers is ulteriorly improved by the ohmic contact,29 as seen in comparative study a series of samples of Zn1–xCdxWO4. Ordinarily, ions doping into the single semiconductor will result in the formation of lattice distortion (plentiful recombination centers), which is one of the momentous reasons for the formation of ohmic contact. This ohmic contact not only can bring down the impedance of the semiconductor and further enhance efficiency of the electrons transport, but also reduce its recombination efficiency of electrons and holes.

Figure 10.

Photoelectrochemical properties, (a) Photocurrent responses of Zn1–xCdxWO4, (b) EIS for the Zn1–xCdxWO4 photoelectrodes, (c) MS of Zn1–xCdxWO4, (d) electronic band structure of Zn1–xCdxWO4.

Figure 10b shows the EIS of Zn1–xCdxWO4. The preferences of bias voltage are set to 0 V and the parameters of frequency are set as 10–3 to 105 Hz. The picture exhibits that circle radius of Zn1–xCdxWO4 gradually brings down with the augment of Cd2+ dosage, which is due to the impedance change caused by the decrease of band gap. This phenomenon can reveal that redox capacity is enhanced and the doping amount of Cd atoms is beneficial to trap excited photoelectrons that further improve the photocatalytic activity.30

In order to accurately estimate the conduction band of Zn1–xCdxWO4, the MS plot is shown in the Figure 10c. From this picture, tangent lines of samples are all demonstrated at a positive slope and the conduction band of Zn1–xCdxWO4 was calculated to be −0.13 eV (ZnWO4), 0.12 eV (Zn0.98Cd0.02WO4), 0.22 eV (Zn0.96Cd0.04WO4), and 0.05 eV (Zn0.94Cd0.06WO4), respectively. On the basis of these data and the results of UV–vis diffuse absorption spectra for Zn1–xCdxWO4, further, the valence band of the samples were estimated to be 3.35 eV (ZnWO4), 3.49 eV (Zn0.98Cd0.02WO4), 3.43 eV (Zn0.96Cd0.04WO4), and 3.22 e (Zn0.94Cd0.06WO4), respectively.

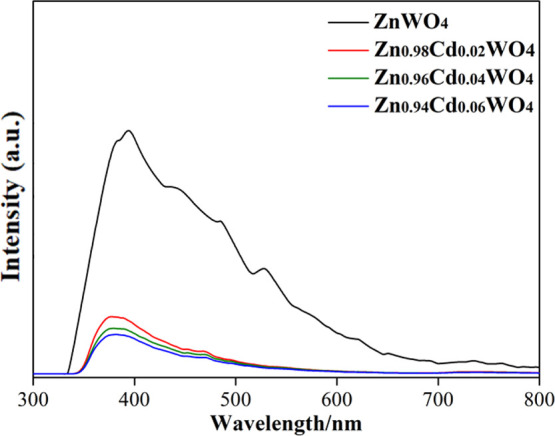

As a rule, effective segregation of photon-generated carriers is deemed to an important index of photocatalyst activity. In order to further investigate the influence of carrier recombination efficiency with the increase of Cd2+ doping amounts in ZnWO4, which the fluorescence was used to inquire with the emission wavelength of the Zn1–xCdxWO4. From Figure 11, all of the strong emission peaks are shown around 400 nm under the 385 nm light excitation. The peak intensities of Zn1–xCdxWO4 gradually enhance with the reduction of Cd2+ dosage. This demonstrates that the separation efficiency of the photon-generated carrier is improved with the augment of Cd2+ dosage. Ion doping is also considered to be a pivotal factor of defect formation,31 and this defect formation is conducive to capture photogenic electrons as well as facilitate holes (h+) to transfer to the photocatalyst’s surface. Ultimately, the synergistic effect of photogenic electron capture and transfer of holes (h+) efficaciously boost the separation efficiency of photoinduced carriers and cause reduction of the photoluminescence (PL) intensity.

Figure 11.

PL spectra of Zn1–xCdxWO4.

2.4. Photocatalytic Mechanism

Based on the above experimental results, we put forward a possible photocatalytic mechanism about the enhancement of photocatalytic activity of Cd-doped ZnWO4, as is shown in Figure 12. It is anticipated that the Zn1–xCdxWO4 exhibits a powerful photocatalytic activity for degradating MO than that of pure ZnWO4, which is benefiting from Cd2+ doping induces the improvement of photogenerated carriers separation efficiency. Also, the subgroup IIB elements are constructed homogeneously distributed Cd-doped ZnWO4 structures, which achieve the goal of multiple absorption of incident light, and therefore aggrandize the production rate of photogenerated electrons and holes. Hence, we think excellent photocatalytic activity of Zn1–xCdxWO4 by the following five reasons: (1) adulteration of Cd contributes to expand the absorption edge to the light region because of some Cd 3d gap states arise on the band gap of ZnWO4. This gap is contributing to amplify the UV region and further enhance the photocatalytic activity. (2) Plentiful Cd atoms uniformly disperse in the ZnWO4 nanorods, which plays a crucial role in the electron traps and further capture of the photoelectron to improve separation efficiency of the carrier. (3) Concomitant Cd2+ can help to facilitate the formation of ohmic contact, and this construction not only can enhance the electrons transport through reducing the resistance of Zn1–xCdxWO4, but also improve its utilization for light quantum. (4) Zn1–xCdxWO4 has a strong oxidizing capacity because of the higher Fermi level, which can generate many free radical. (5) Incorporation of Cd may produce many defects and it is benefit to enhance the conductivity (movement of holes mobility and other ions) of Zn1–xCdxWO4. Ultimately, the photocatalytic activity can be markedly promoted.

Figure 12.

Photocatalytic mechanism of Zn1–xCdxWO4.

3. Conclusions

In summary, the Zn1–xCdxWO4 nanorods were triumphantly synthesized by a templateless tactics. The Zn1–xCdxWO4 nanoarchitectures display glorious photocatalytic performance compared with pristine ZnWO4 for degrading MO in sewage. To shed more light on evidence on the root of the boosted photocatalytic activity of the doped ZnWO4 nanoarchitectures, a great deal of characterizations were implemented. Mechanistic researches were executed for getting insights into the photocatalytic degradation process, and the excellent photocatalytic performance of the doped ZnWO4 nanoarchitectures is attributed to the enhanced optical absorbance, efficient segregation, and transfer of photoinduced charge carriers deriving from doping effects. The doped nanoarchitectures of this work have promising applications in the territories such as environment and energy chemistry, and the strategy is of great value for the design and synthesis of other functionalized nanoarchitectures.

4. Experimental Section

4.1. Chemicals

Zinc acetate (C4H6O4Zn·2H2O) and sodium tungstate dehydrate (Na2WO4·2H2O) were purchased from Chendu Chron Chemicals Corporation. Cadmium chloride (CdCl2·2.5H2O) was purchased from Tianjing Fuchen Chemicals Corporation. All chemical reagents were analytically pure, and without any other purification.

4.2. Synthesis

4.2.1. ZnWO4

ZnWO4 were synthesized by a following portable synthesis scheme. First, C4H6O4Zn·2H2O (3 mmol) was dissolved in the deionized water (15 mL). Second, the solution of Na2WO4·2H2O (3 mmol, 30 mL) was slowly added into the C4H6O4Zn·2H2O solution as well as vigorous stirring for 1 h. Third, the mixed solution was transferred into 100 mL Teflon-lined stainless steel autoclave and afterward reacted at 180 °C for 16 h. Ultimately, the samples were washed to neutral and dried at 100 °C about 1 h. The sample is named as ZnWO4.

4.2.2. Zn1–xCdxWO4

In a classic synthetic scheme (Figure 13), 3 mmol C4H6O4Zn·2H2O and 15 mL of H2O were injected into CdCl2·2.5H2O solution (the ratios of Cd to Zn ions were 0.02, 0.04, and 0.06, respectively). After stirring for 1 h, 3 mmol Na2WO4·2H2O and 30 mL of H2O were slowly added into the above mixture solution with vigorously stirring for 1 h. Then, the intermediate products were transferred into 100 mL Teflon-lined stainless-steel autoclave as well as conducting ultrasonic treatment. Finally, the intermediate products were kept at 180 °C for 12 h. After the samples were cooled down, they was washed to neutral and dried at 100 °C about 1 h. The samples are named as Zn0.98Cd0.02WO4, Zn0.96Cd0.04WO4, and Zn0.94Cd0.06WO4, respectively.

Figure 13.

Schematic illustration of the preparation of Zn1–xCdxWO4.

4.3. Characterization

The crystal structure and phase of the nanostructures were explored via an XRD instrument (PANalytical X’Pert PRO). The composition and surface state of the samples were determined using XPS (Thermo Fisher Scientific K-Alpha). The chemical composition and morphology of samples were conducted on a scanning electron microscope (Carl Zeiss Ultra 55) with an energy dispersive X-ray probing unit. TEM, together with EDX spectra and element distribution measurements of the architectures were performed using a Carl Zeiss LIBRA 200FE transmission electron microscope operating at 200 kV. The UV–vis DRS and photocatalytic activity of the nanostructures were investigated by the Shimadzu SolidSpec-3700 UV–vis spectrophotometer, and BaSO4 was used as reflectance standard is. The separation characteristic of photogenic charge carrier for the nanostructure was researched by a fluorescence spectrophotometer (F-4600). Electrochemical measurements were carried out by using Shanghai Chenhua electrochemical workstation (CHI660E).

4.4. Photocatalytic Experiments

The photocatalytic activity of the samples was estimated from the removal rate of MO. The ultraviolet source (5.0 mW cm–2, λ = 310 nm) was selected as excitation light. First, 30 mg of samples were put into the MO solutions (10 mg L–1, 50 mL) and the pH of heterogeneous system is adjusted to 7.0. Next, in order to achieve sample dispersion and adsorption equilibrium, all of the heterogeneous system of the vessels were subject to ultrasound about 20 min and sustained tempestuously oscillation about 20 min under the dark. Then, a high pressure mercury lamp as a simulated ultraviolet was distanced from quartz beaker about 15 cm, and the quartz beaker was exposed to this ultraviolet source about 5 h. While the photocatalytic degradation was in progress, 3 mL of liquid supernatant was centrifugated every 1 h. The supernate after centrifugal was measured at 464 nm and calculated the removal rate with the following formula 2

| 2 |

The initial concentration of MO solution is represented by C0, and Ct is on behalf of postdegradation concentration of MO solution. The concentration unit of C0 and Ct is mg L–1.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Application Foundation of Science and Technology Department of Sichuan Province (2020YJ0419) and the Fundamental Science on Nuclear Wastes and Environmental Safety Laboratory (19kfhk04).

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsomega.0c02541.

Additional details of the comparison of photocatalytic performance, the data of kinetic constants, and the kinetic model of four cyclic tests (PDF)

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- a Li S.; Chen J.; Hu S.; Wang H.; Jiang W.; Chen X. Facile Construction of Novel Bi2WO6/Ta3N5 Z-Scheme Heterojunction Nanofibers for Efficient Degradation of Harmful Pharmaceutical Pollutants. Chem. Eng. J. 2020, 402, 126165. 10.1016/j.cej.2020.126165. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Chen Y.; Xiao B.; Chang J.; Fu Y.; Lv P.; Wang X. Synthesis of Siodiesel from Waste Cooking Oil using Immobilized Lipase in Fixed Bed Reactor. Energy Convers. Manage. 2009, 50, 668–673. 10.1016/j.enconman.2008.10.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; c Baral B.; Mansingh S.; Reddy K. H.; Bariki R.; Parida k. Architecting a Double Charge-Transfer Dynamics In2S3/BiVO4 n–n Isotype Heterojunction for Superior Photocatalytic Oxytetracycline Hydrochloride Degradation and Water Oxidation Reaction: Unveiling the Association of Physicochemical, Electrochemical, and Photocatalytic Properties. ACS Omega 2020, 5, 5270–5284. 10.1021/acsomega.9b04323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Roy N.; Suzuki N.; Terashima C.; Fujishima A. Recent Improvements in the Production of Solar Fuels: From CO2 Reduction to Water Splitting and Artificial Photosynthesis. Bull. Chem. Soc. Jpn. 2019, 92, 178–192. 10.1246/bcsj.20180250. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Zeng D.; Yang K.; Yu C.; Chen F.; Li X.; Wu Z.; Liu H. Phase Transformation and Microwave Hydrothermal Guided a Novel Double Z-Scheme Ternary Vanadate Heterojunction with Highly Efficient Photocatalytic Performance. Appl. Catal., B 2018, 237, 449–463. 10.1016/j.apcatb.2018.06.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- a Li S.; Chen J.; Hu S.; Jiang W.; Liu Y.; Liu J. A Novel 3D Z-scheme Heterojunction Photocatalyst: Ag6Si2O7 Anchored on Flower-Like Bi2WO6 and Its Excellent Photocatalytic Performance for the Degradation of Toxic Pharmaceutical Antibiotics. Inorg. Chem. Front. 2020, 7, 529–541. 10.1039/c9qi01201j. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Li S.; Hu S.; Jiang W.; Zhang J.; Xu K.; Wang Z. In situ Construction of WO3 Nanoparticles Decorated Bi2MoO6 Microspheres for Boosting Photocatalytic Degradation of Refractory Pollutants. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2019, 556, 335–344. 10.1016/j.jcis.2019.08.077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Fu J.; Xu Q.; Low J.; Jiang C.; Yu J. Ultrathin 2D/2D WO3/g-C3N4 Step-Scheme H2-production Photocatalyst. Appl. Catal., B 2019, 243, 556–565. 10.1016/j.apcatb.2018.11.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z.; Li C.; Domen k. Recent Developments in Heterogeneous Photocatalysts for Solar-driven Overall Water Splitting. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2019, 48, 2109–2125. 10.1039/c8cs00542g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Ozawa A.; Yamamoto M.; Tanabe T.; Yoshida T. TiOxNy/TiO2 Photocatalyst for Hydrogen Evolution under Visible-light Irradiation. I: Characterization of N in TiOxNy/TiO2 Photocatalyst. ACS Omega 2019, 4, 20424–20429. 10.1021/acsomega.9b02977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Roongraung K.; Chuangchote S.; Laosiripojana N.; Sagawa T. Electrospun Ag-TiO2 Nanofibers for Photocatalytic Glucose Conversion to High-Value Chemicals. ACS Omega 2020, 5, 5862–5872. 10.1021/acsomega.9b04076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Haarstrick A.; Kut O. M.; Heinzle E. TiO2 Assisted Degradation of Environmentally Relevant Organic Compounds in Wastewater Using a Novel Fluidized Bed Photoreactor. Environ. Sci. Technol. 1996, 30, 817–824. 10.1021/es9502278. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- a Liu D.; Lv Y.; Zhang M.; Liu Y.; Zhu Y.; Zong R.; Zhu Y. Defect-Related Photoluminescence and Photocatalytic Properties of Porous ZnO Nanosheets. J. Mater. Chem. A 2014, 2, 15377–15388. 10.1039/c4ta02678k. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Chen Y.-C.; Li Y.-J.; Hsu Y.-K. Enhanced Performance of ZnO-Based Dye-Sensitized Solar Cells by Glucose Treatment. J. Alloys Compd. 2018, 748, 382–389. 10.1016/j.jallcom.2018.03.189. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; c Nassar M. Y.; Ali A. A.; Amin A. S. A Facile Pechini Sol-Gel Synthesis of TiO2/Zn2TiO2/ZnO/C Nanocomposite: an Efficient Catalyst for the Photocatalytic Degradation of Orange G Textile Dye. RSC Adv. 2017, 7, 30411–30421. 10.1039/c7ra04899h. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hu J.-S.; Ren L.-L.; Guo Y.-G.; Liang H.-P.; Cao A.-M.; Wan L.-J.; Bai C.-L. Mass Production and High Photocatalytic Activity of ZnS Nanoporous Nanoparticles. Angew. Chem. 2005, 117, 1295–1299. 10.1002/ange.200462057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Lin J.; Lin J.; Zhu Y. Controlled Synthesis of the ZnWO4 Nanostructure and Effects on the Photocatalytic Performance. Inorg. Chem. 2007, 46, 8372–8378. 10.1021/ic701036k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Li P.; Zhao X.; Jia C.-j.; Sun H.; Sun L.; Cheng X.; Liu L.; Fan W. ZnWO4/BiOI Heterostructures with Highly Efficient Visible Light Photocatalytic Activity: the Case of Interface Lattice and Energy Level Match. J. Mater. Chem. A 2013, 1, 3421–3429. 10.1039/c3ta00442b. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; c Yu C.; Yu J. C. Sonochemical Fabrication, Characterization and Photocatalytic Properties of Ag/ZnWO4 Nanorod Catalyst. Mater. Sci. Eng., B 2009, 164, 16–22. 10.1016/j.mseb.2009.06.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; d Li D.; Shi R.; Pan C.; Zhu Y.; Zhao H. Influence of ZnWO4 Nanorod Aspect Ratio on the Photocatalytic Activity. CrystEngComm 2011, 13, 4695–4700. 10.1039/c1ce05256j. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Xu J.; Cao X. Characterization and Mechanism of MoS2/CdS Composite Photocatalyst Used for Hydrogen Production from Water Splitting under Visible Light. Chem. Eng. J. 2015, 260, 642–648. 10.1016/j.cej.2014.07.046. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Y.; Hu W.; Xie R.; Liu X.; Yang D.; Chen P.; Zhang J.; Zhang F. Composite of Nano-goethite and Natural Organic Luffa Sponge as Template: Synergy of High Efficiency Adsorption and Visible-Light Photocatalysis. Inorg. Chem. Commun. 2018, 98, 115–119. 10.1016/j.inoche.2018.09.032. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Siriwong P.; Thongtem T.; Phuruangrat A.; Thongtem S. Hydrothermal Synthesis, Characterization, and Optical Properties of Wolframite ZnWO4 Nanorods. CrystEngComm 2011, 13, 1564–1569. 10.1039/c0ce00402b. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hojamberdiev M.; Zhu G.; Xu Y. Template-Free Synthesis of ZnWO4 Powders Via Hydrothermal Process in a Wide pH Range. Mater. Res. Bull. 2010, 45, 1934–1940. 10.1016/j.materresbull.2010.08.015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu J.; Liu M.; Tang Y.; Sun T.; Ding J.; Han L.; Wang M. Facile Photochemical Synthesis of ZnWO4/Ag Yolk-Shell Microspheres with Enhanced Visible-Light Photocatalytic Activity. Mater. Lett. 2017, 190, 60–63. 10.1016/j.matlet.2016.12.056. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Huang G.; Zhang C.; Zhu Y. ZnWO4 Photocatalyst with High Activity for Degradation of Organic Contaminants. J. Alloys Compd. 2007, 432, 269–276. 10.1016/j.jallcom.2006.05.109. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- a Zhang K.; Lin L.; Hussain S.; Han S. Core-Shell NiCo2O4@ZnWO4 Nanosheets Arrays Electrode Material Deposited at Carbon-Cloth for Flexible Electrochemical Supercapacitors. J. Mater. Sci.: Mater. Electron. 2018, 29, 12871–12877. 10.1007/s10854-018-9406-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Li D.; Xue J.; Bai X. Synthesis of ZnWO4/CdWO4 Core-Shell Structured Nanorods Formed by Oriented Attachment Mechanism with Enhanced Photocatalytic Performances. CrystEngComm 2016, 18, 309–315. 10.1039/c5ce01858g. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Leonard K. C.; Nam K. M.; Lee H. C.; Kang S. H.; Park H. S.; Bard A. J. ZnWO4/WO3 Composite for Improving Photoelectrochemical Water Oxidation. J. Phys. Chem. C 2013, 117, 15901–15910. 10.1021/jp403506q. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- a Maeda K.; Mallouk T. E. Two-Dimensional Metal Oxide Nanosheets as Building Blocks for Artificial Photosynthetic Assemblies. Bull. Chem. Soc. Jpn. 2019, 92, 38–54. 10.1246/bcsj.20180258. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Li S.; Hu S.; Jiang W.; Liu Y.; Zhou Y.; Liu J.; Wang Z. Facile Synthesis of Cerium Oxide Nanoparticles Decorated Flower-Like Bismuth Molybdate for Enhanced Photocatalytic Activity toward Organic Pollutant Degradation. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2018, 530, 171–178. 10.1016/j.jcis.2018.06.084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Paul D. R.; Gautam S.; Panchal P.; Nehra S. P.; Choudhary P.; Sharma A. ZnO-Modified g-C3N4: A Potential Photocatalyst for Environmental Application. ACS Omega 2020, 5, 3828–3838. 10.1021/acsomega.9b02688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Y.; Luo N.; Xie R. Enhanced Visible-Light Photocatalytic Performance of CdS/Zn1–xCdxWO4 Composites Prepared by a Facile Protocol. Ceram. Int. 2020, 46, 14114–14123. 10.1016/j.ceramint.2020.02.216. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Geng Y.; Ma J.; Hou Z.; Li N.; Wang L. Enhanced Photocatalytic Activity of ZnWO4/BiOI Composites under Visible-Light Irradiation. J. Nanosci. Nanotechnol. 2019, 19, 7771–7776. 10.1166/jnn.2019.16771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Y.; Tie J.; Chen C.; Luo N.; Yang D.; Hu W.; Liu X. Synthesis of LAS/ZnO/ZnWO4 3D Rod-Like Heterojunctions with Efficient Photocatalytic Performance: Synergistic Effects of Highly Active Site Exposure and Low Carrier Recombination. Ceram. Int. 2019, 45, 13656–13663. 10.1016/j.ceramint.2019.04.027. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- a Gombac V.; Montini T.; Polizzi S.; Jaén J. J. D.; Hameed A.; Fornasiero P. Photocatalytic Production of Hydrogen over Ttailored Cu-embedded TiO2. Nanosci. Nanotechnol. Lett. 2009, 1, 128–133. 10.1166/nnl.2009.1017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Lu X.; Xu K.; Chen P.; Jia K.; Liu S.; Wu C. Facile One Step Method Realizing Scalable Production of g-C3N4 Nanosheets and Study of Their Photocatalytic H2 Evolution Activity. J. Mater. Chem. A 2014, 2, 18924–18928. 10.1039/c4ta04487h. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; c Liu Y.; Li J.; Zhou B.; Li X.; Chen H.; Chen Q.; Wang Z.; Li L.; Wang J.; Cai W. Efficient Electricity Production and Simultaneously Wastewater Treatment Via a High-Performance Photocatalytic Fuel Cell. Water Res. 2011, 45, 3991–3998. 10.1016/j.watres.2011.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang G.; Zhu Y. Enhanced Photocatalytic Activity of ZnWO4 Catalyst via Fluorine Doping. J. Phys. Chem. C 2007, 111, 11952–11958. 10.1021/jp071987v. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- a Ye D.; Li D.; Zhang W.; Sun M.; Hu Y.; Zhang Y.; Fu X. A New Photocatalyst CdWO4 Prepared with a Hydrothermal Method. J. Phys. Chem. C 2008, 112, 17351–17356. 10.1021/jp8059213. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Li D.; Bai X.; Xu J.; Ma X.; Zhu Y. Synthesis of CdWO4 Nanorods and Investigation of the Photocatalytic Activity. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2014, 16, 212–218. 10.1039/c3cp53403k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Z.; Tian J.; Zeng D.; Yu C.; Zhu L.; Huang W.; Yang K.; Li D. A Facile Microwave-Hydrothermal Method to Fabricate B Doped ZnWO4 Nanorods with High Crystalline and Highly Efficient Photocatalytic Activity. Mater. Res. Bull. 2017, 94, 298–306. 10.1016/j.materresbull.2017.06.021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- a Song X. C.; Zheng Y. F.; Yang E.; Liu G.; Zhang Y.; Chen H. F.; Zhang Y. Y. Photocatalytic Activities of Cd-doped ZnWO4 Nanorods Prepared By a Hydrothermal Process. J. Hazard. Mater. 2010, 179, 1122–1127. 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2010.03.123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Pullar R. C.; Farrah S.; Alford N. M. MgWO4, ZnWO4, NiWO4 and CoWO4 Microwave Dielectric Ceramics. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 2007, 27, 1059–1063. 10.1016/j.jeurceramsoc.2006.05.085. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- a Lou Z.; Hao J.; Cocivera M. Luminescence of ZnWO4 and CdWO4 Thin Films Prepared by Spray Pyrolysis. J. Lumin. 2002, 99, 349–354. 10.1016/s0022-2313(02)00372-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Xie R.; Li Y.; Liu H.; Zhang X. Insights into the Structural, Microstructural and Physical Properties of Multiphase Powder Mixtures. J. Alloys Compd. 2017, 691, 378–387. 10.1016/j.jallcom.2016.08.266. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; c Meng J.; Chen T.; Wei X.; Li J.; Zhang Z. Template-Free Hydrothermal Synthesis of MgWO4 Nanoplates and Their Application as Photocatalysts. RSC Adv. 2019, 9, 2567–2571. 10.1039/c8ra06671j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Huang G.; Zhu Y. Synthesis and Photocatalytic Performance of ZnWO4 Catalyst. Mater. Sci. Eng., B 2007, 139, 201–208. 10.1016/j.mseb.2007.02.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Ye D.; Li D.; Zhang W. J.; Sun M.; Hu Y.; Zhang Y. F.; Fu X. Z. A New Photocatalyst CdWO4 Prepared with a Hydrothermal Method. J. Phys. Chem. C 2008, 112, 17351–17356. 10.1021/jp8059213. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu Y.; Shah M. W.; Wang C. Insight into the Role of Ti3+ in Photocatalytic Performance of Shuriken-Shaped BiVO4/TiO2-x Heterojunction. Appl. Catal., B 2017, 203, 526–532. 10.1016/j.apcatb.2016.10.056. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yan F.; Wang Y.; Zhang J.; Lin Z.; Zheng J.; Huang F. Schottky or Ohmic Metal-Semiconductor Contact: Influence on Photocatalytic Efficiency of Ag/ZnO and Pt/ZnO Model Systems. ChemSusChem 2014, 7, 101–104. 10.1002/cssc.201300818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X.; Pan L.; Lv T.; Zhu G.; Sun Z.; Sun C. Microwave-Assisted Synthesis of CdS-Reduced Graphene Oxide Composites for Photocatalytic Reduction of Cr(VI). Chem. Commun. 2011, 47, 11984–11986. 10.1039/c1cc14875c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amade R.; Heitjans P.; Indris S.; Finger M.; Haeger A.; Hesse D. Defect Formation during High-Energy Ball Milling in TiO2 and Its Relation to the Photocatalytic Activity. J. Photochem. Photobiol., A 2009, 207, 231–235. 10.1016/j.jphotochem.2009.07.015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.