Abstract

Supercritical water gasification (SCWG) of mixtures of guaiacol and acetic acid was carried out in a continuous reactor at 600 °C and 25 MPa with a residence time of 94 s. Different concentrations of acetic acid were employed to investigate the effect of acetic acid on product yield and gas composition. The interaction between guaiacol and acetic acid during SCWG was discussed. Acetic acid, as a radical scavenger, was found to inhibit radical polymerization, resulting in the suppression of char formation.

1. Introduction

Supercritical water gasification (SCWG) is a unique process for transforming lignocellulosic biomass with high water content into value-added products.1−4 Under SCWG conditions (above 22.1 MPa and 374 °C), even hydrophobic organic compounds can dissolve in water to form a single phase because the physical properties of water change from polar to nonpolar. In addition, at lower water densities, supercritical water acts as both a solvent and a catalyst by releasing free radicals (H• and OH•) that actively participate in the decomposition of organic compounds.5 Thus, these free radicals can suppress the production of char and tar by decomposing intermediates to produce these unwanted products. However, even a trace amount of solid products can cause reactor plugging during the long-term operation, and also lowering the carbon gasification efficiency (CGE).6 In our previous study,6−8 we found that the char and tar yields from the SCWG of biomass depended on the process parameters, such as temperature, feedstock concentration, residence time, and catalyst, based on which we discussed the char formation mechanism. Understanding this mechanism is important in determining the conditions to suppress unwanted reactions. There are two different char formation mechanisms: ionic and radical. Promdej et al. reported that glucose, a model compound of cellulose, produces char via an ionic reaction,9 whereas Afifi et al. reported that anisole, the linkage model of lignin and coal, produces highly reactive and unstable free radicals that may further react via rearrangement, electron abstraction, or radical–radical interaction to form increasingly stable products.10 Yong and Matsumura obtained similar results using guaiacol as a model compound of lignin to form char in supercritical water via a radical reaction.7 Vuori and Bredenberg11 proposed a concerted reaction and a free radical reaction to be the key to understanding the pyrolytic decomposition of guaiacol. Based on product characterization results, Asmadi et al.12 suggested that the homolysis of a methoxy O–CH3 bond is the major route for pyrolytic decomposition of guaiacol. Dorrestijn et al.13 proposed that guaiacol degradation occurred after the breaking of an O–H bond to form salicylaldehyde. Scheer et al.14 studied the pyrolysis of guaiacol in a heated SiC microtubular reactor and found that the first step of guaiacol decomposition is the loss of a methyl radical and that a hydroxy-cyclopentadienyl radical is produced via decarbonylation of a 2-hydroxyl phenoxy radical.

Considering the importance of radical reactions in guaiacol decomposition, radical scavengers should be effective in suppressing radical reactions to form high-molecular-weight products. A previous study by our group15 showed that char formation during guaiacol decomposition in SCWG could be suppressed by adding organic acids as radical scavengers. However, the optimization of the amount of radical scavengers required to suppress char and the effect of radical scavenger concentration on product yield and gas composition have not yet been elucidated. To this end, the interaction between guaiacol and radical scavengers like acetic acid must be elucidated; however, to the best of our knowledge, no study has been conducted on the interaction between guaiacol and acetic acid under supercritical conditions.

Therefore, the purpose of this study was to evaluate the effect of acetic acid as a radical scavenger on the product yield and gas composition from guaiacol SCWG from the viewpoint of the interaction between guaiacol and acetic acid.

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. SCWG of Acetic Acid as a Radical Scavenger

Acetic acid is a key model compound that has been identified as a radical scavenger to suppress char formation in the SCWG of guaiacol and shochu residue.15 The gasification product of acetic acid alone should be of importance. The SCWG of acetic acid at various concentrations (0–2.0 wt %) was conducted first, and the corresponding carbon yields at 600 °C and 25 MPa with a residence time of 94 s are shown in Figure 1. In this figure, the same values in the horizontal axis mean the reproducibility check. As acetic acid concentration was increased from 0.5 to 2.0 wt %, the total organic carbon (TOC) yield increased significantly from 0.01 to 0.62, whereas CGE decreased from 1 to 0.41.

Figure 1.

Effect of concentration of acetic acid on carbon product yield from SCWG of acetic acid at 600 °C, 25 MPa, and 94 s

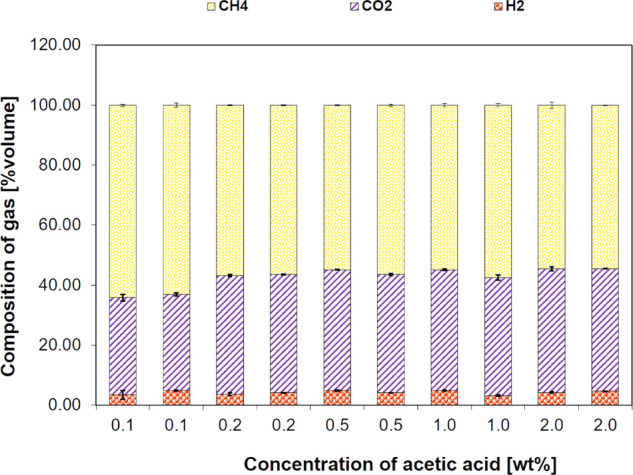

The gas composition results shown in Figure 2 indicated that CH4 and CO2 are the main components of the gaseous product. In this figure, the same values in the horizontal axis mean the reproducibility check. Similar results were obtained for acetic acid decomposition at temperatures above 450 °C.16 It is known that homogeneous dehydration and decarboxylation occur via the dominant radical reaction.17−22 Considering the large amount of water under the hydrothermal reaction field, dehydration should not be favored. Acetic acid under SCWG conditions can continuously produce hydroxy, methyl, and carboxyl radicals.15,23

Figure 2.

Effect of concentration of acetic acid on gas product composition from SCWG of acetic acid at 600 °C, 25 MPa, and 94 s

2.2. SCWG of a Guaiacol/Acetic Acid Mixture

In this study, acetic acid is expected to produce small radicals during gasification. Therefore, the effectiveness of adding acetic acid as a radical scavenger to the decomposition of guaiacol under supercritical conditions is examined. Figure 3 illustrates the effect of acetic acid concentration on the product yield and gas composition from the SCWG of guaiacol at 600 °C, 25 MPa, and a residence time of 94 s. In this figure, the same values in the horizontal axis mean the reproducibility check. A high amount of acetic acid resulted in reduced char and tar yields, while gasification of acetic acid itself did not produce any char and tar. CGE was not affected greatly by the acetic acid concentration.

Figure 3.

Effect of concentration of guaiacol/acetic acid mixture on carbon product yield from SCWG of acetic acid at 600 °C, 25 MPa, and 94 s

Figure 4 describes the effect of acetic acid concentration on the product gas composition obtained from gasification of the guaiacol/acetic acid mixture. In this figure, the same values in the horizontal axis mean the reproducibility check. The main component of the gaseous product was different from that obtained from only acetic acid gasification due to the presence of H2, CO, CO2, and CH4 obtained from the decomposition of guaiacol.8 The CO2 and CH4 contents increased with increasing acetic acid concentration, apparently due to the generation of CO2 and CH4 from acetic acid (Figure 2). In contrast, contents of CO and H2, which are mainly from guaiacol, are reduced with increasing acetic acid concentration.

Figure 4.

Effect of concentration of guaiacol/acetic acid mixture on gas product composition from SCWG of acetic acid at 600 °C, 25 MPa, and 94 s

2.3. Interaction between Guaiacol and Acetic Acid in SCWG

It should be noted that when there is no interaction between guaiacol and acetic acid, the interaction parameter (γ) defined in eq 3 is equal to 1.0. A large deviation of the interaction parameter (γ) from 1.0 indicates a strong interaction. The no-interaction case can be expressed by the straight line in the graph showing the effect of the acetic acid carbon fraction, as shown in Figures 5 and 6. These figures show whether the interaction results in the enhanced or suppression of production and to what extent. Deviation from the straight lines shows the interaction between guaiacol and acetic acid. If the plot is higher than the line, the interaction resulted in enhanced production and vice versa. Note that the results obtained for acetic acid alone are the ones for the corresponding acetic acid concentration.

Figure 5.

Carbon yields (TOC, CGE, char, and tar) of the guaiacol and acetic acid mixture in SCWG at 600 °C and 25 MPa for different fractions of acetic acid.

Figure 6.

H2, CO, CO2, CH4, C2H4, and C2H6 yields of the guaiacol and acetic acid mixture in SCWG at 600 °C and 25 MPa for different fractions of acetic acid.

The interaction parameters thus determined are shown in Figures 7 and 8 as a function of the acetic acid carbon fraction. By definition, the interaction parameter for pure guaiacol or pure acetic acid was 1.0. When the interaction enhances product yield, an interaction parameter higher than 1.0 is obtained and vice versa. These figures suggest that the interaction between guaiacol and acetic acid enhances the production of TOC and H2 but suppresses the production of gas, tar, char, CO, and CH4.

Figure 7.

Interaction parameter (γ) of each product distribution (TOC, CGE, char, and tar) of the guaiacol/acetic acid mixture at different mole-C fractions of acetic acid.

Figure 8.

Interaction parameter (γ) of each gas composition of guaiacol/acetic acid mixture at different mole-C fractions of acetic acid.

Acetic acid should produce methyl radicals and carboxyl radicals, and the latter is decomposed into CO2 and hydrogen radicals. Meanwhile, the hydroxy group of guaiacol can also produce hydrogen radicals. These hydrogen radicals from acetic acid and guaiacol can produce H2, which explains the enhancement of H2 production.

Suppression of CO and CH4 implies that the methoxy radical from guaiacol is consumed by the acetic acid. Both CO and CH4 are produced directly from guaiacol.8 Considering the stability of the benzene ring, these molecules should be produced from the methoxy group of guaiacol via methoxy radical formation. The addition of acetic acid reduces the yield of these gases; thus, acetic acid apparently interacts with the methoxy radical.

2.4. Comparison of the Mechanism of Char Suppression by the Radical Scavenger

In lignocellulosic biomass, cellulose and lignin are the major contributors to char production by SCWG. However, these biomass components produce char via different mechanisms, viz., ionic and radical reactions. A recent study15 suggested that acetic acid is an interesting organic compound that can be added to suppress char formation under supercritical conditions. For the shochu residue, char production was found to increase upon adding more than 0.01–0.03 wt % acetic acid via an ionic reaction. Figure 9 compares the effect of acetic acid addition on the SCWG of the shochu residue and that of guaiacol in this study. For guaiacol, acetic acid suppresses char production even at concentrations as high as 2 wt %.

Figure 9.

Product char from the shochu residue–acetic acid mixture and the guaiacol–acetic acid mixture that added acetic acid and weight average (dash line).

Considering that radical scavengers suppress the production of char via radical reactions, which is typical for lignin and guaiacol, very low lignin content for the shochu residue should be the reason for the very low char yield attained upon adding only acetic acid at a carbon mole fraction of 0.02, while complete suppression of char from guaiacol required as much as 0.2. Shochu residue is the residue of liquor distillation and thus contains a very small amount of lignin. For guaiacol, a sufficient amount of acetic acid can completely suppress char production. Up to the acetic acid carbon fraction of 0.2, the char yield is suppressed linearly, implying a stoichiometric reaction mechanism. Since one molecule of guaiacol has seven carbon atoms, stoichiometry in terms of carbon should be 7:2 for guaiacol to acetic acid. In other words, one mole of acetic acid should be added to one mole of guaiacol to suppress char production.

As discussed in the previous section, methoxy radicals appear to interact with acetic acid. If the methoxy radical reacts with the remaining radical part of the guaiacol to produce char, acetic acid should react with these two radicals to prevent char formation. One mole of acetic acid for one mole of guaiacol is reasonable. The schematic effect of acetic acid addition proposed here is shown in Figure 10.

Figure 10.

Schematic effect of acetic acid addition on char production from guaiacol.

Based on this model, the interaction parameter for char decreases linearly with increasing acetic acid carbon fraction, reaches zero at 2/9 = 0.222, and remains at zero for larger acetic acid carbon fractions because the char yield is zero. This theoretical line is also shown in Figure 7. Verification of this model requires further analysis of the product, which is beyond the scope of this study. However, this model explains the experimentally obtained behavior of the interaction parameter for the char, which is the most important undesirable byproduct of SCWG.

3. Experimental Section

3.1. Materials and Experimental Procedures

Guaiacol (98%) from Tokyo Chemical Industry Co., Ltd. (Japan), acetic acid (99%) from Nacalai Tesque, Inc. (Japan), and deionized water (<1 μS/cm) were used in this study. A stainless steel (SS316) tube with an inner diameter of 2.17 mm, outer diameter of 3.17 mm, and a length of 12 m was used as a continuous reactor. A detailed description of this reactor and its operating procedures have been reported in a previous paper.8 Briefly, we prepared a range of mixtures of 0.5 wt % guaiacol and various concentrations of acetic acid (0–2.0 wt %). The mixtures were fed into the reactor at a temperature of 600 °C and a pressure of 25 MPa using a high-pressure pump at a flow rate of 2.0 mL/min to achieve a fixed residence time of 94 s. All the samples were collected after conducting the experiment for 2 h to reach the steady state. The reactor effluent was collected after cooling in the heat exchanger and depressurization in the back-pressure regulator. The effluent was composed of gas- and liquid-phase water containing organics (hereafter called total organic carbon, TOC). The gas generation rate was determined by measuring the time required for the product gas to fill a 14 cm3 vial by liquid replacement. To collect the solid product, we placed in-line filters and measured their weight increase. In this study, the thus-collected solid product is called char. It was found that, to obtain the mass balance, the solid product left in the reactor could not be neglected. Therefore, after the experiment, the reactor was washed with a methanol–acetone mixture and then with water to recover the product remaining in the reactor, and after drying, its weight was measured. In this study, this solid product is called tar. Thus, four types of products were collected: gas, TOC, char, and tar. All of the runs were conducted more than twice.

3.2. Analytical and Calculation Methods

Gas chromatography (GC, Shimadzu Co., GC-14B) employed two detectors, viz, a thermal conductivity detector (TCD) and a flame ionization detector (FID), for the analysis of gaseous products. TCD was used to detect H2 using N2 as the carrier gas and to detect CO2 and CO using He as the carrier gas. FID was used to analyze CH4, C2H4, and C2H6 using He as the carrier gas. A TOC analyzer (TOC-V CPH, Shimadzu Co.) was used to determine the amount of organics in the liquid product (nonpurgeable organic carbon, NPOC) and dissolved in carbon dioxide (inorganic carbon, IC).

One of the in-line filters with a pore size of 2 μm was utilized to collect the char product for a sampling time of 30 min under a steady-state operation. The black solid trapped in this filter was removed and weighed after drying at 105 °C. This solid amount was divided by the sampling time to obtain the char production rate. The tar product was dried at 105 °C until a constant weight of the remaining sticky surface material was attained.

The carbon yield Y [mol-C/mol-C] of product X was calculated based on the molar amount of carbon atoms using eq 1.

| 1 |

where nC (X) [mol-C], nC,0 (guaiacol) [mol-C], and nC,0 (acetic acid) [mol-C] are the molar amounts of carbon in product X, initial molar amount of carbon in guaiacol, and that in acetic acid, respectively. To obtain hydrogen yield, a molar amount of hydrogen was used in place of nC (X). Char and tar were assumed to comprise only carbon.24,25 It should be noted that the carbon yield of gas is the CGE.

3.3. Interaction Parameter Analysis

Assuming that the behaviors of guaiacol and acetic acid in the mixture are independent of each other, the calculated yield for the mixture Y(calc) [mol/mol-C] can be obtained from the carbon yield for guaiacol Y(g) [mol/mol-C] and that for only acetic acid Y(a) [mol/mol-C] using the following equation eq 2.

| 2 |

where xC,g [mol-C/mol-C] and xC,a [mol-C/mol-C] are the molar fractions of carbon in guaiacol and acetic acid, respectively. The ratio of the experimentally obtained yield Y(exp) to the calculated yield Y(calc) defines the interaction parameter, γ as shown in eq 3.

| 3 |

4. Conclusions

In this study, it was found that acetic acid is a good radical scavenger for inhibiting radical char formation from guaiacol under SCWG conditions. The experiments demonstrated that a significant interaction exists between guaiacol and acetic acid during the SCWG process. The interaction parameters indicated that adding acetic acid has a significant effect on the product yields, especially the char yield. The addition of acetic acid at a carbon fraction higher than 0.22 resulted in no char production. This corresponds to the equimolar ratio of guaiacol and acetic acid, implying that a stoichiometric reaction mechanism operates for char suppression upon adding acetic acid.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

References

- Matsumura Y.; Minowa T.; Potic B.; Kersten S. R. A.; Prins W.; van Swaaij W. P. M.; van de Beld B.; Elliott D. C.; Neuenschwander G. G.; Kruse A.; Antal M. J. Biomass gasification in near- and super-critical water: Status and prospects. Biomass Bioenergy 2005, 29, 269–292. 10.1016/j.biombioe.2005.04.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Matsumura Y.; Hara S.; Kaminaka K.; Yamashita Y.; Yoshida T.; Inoue S.; Kawai Y.; Minowa T.; Noguchi T.; Shimizu Y. Gasification Rate of Various Biomass Feedstocks in Supercritical Water. J. Jpn. Pet. Inst. 2013, 56, 1–10. 10.1627/jpi.56.1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Antal J. M. J. Jr.; Helsen L. M.; Kouzu M.; Lédé J.; Matsumura Y. Rules of Thumb (Empirical Rules) for the Biomass Utilization by Thermochemical Conversion. J. Jpn. Inst. Energy 2014, 93, 684–702. 10.3775/jie.93.684. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kruse A.; Gawlik A. Biomass Conversion in Water at 330–410 °C and 30–50 MPa. Identification of Key Compounds for Indicating Different Chemical Reaction Pathways. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2003, 42, 267–279. 10.1021/ie0202773. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nanda S.; Reddy S. N.; Hunter H. N.; Butler I. S.; Kozinski J. A. Supercritical Water Gasification of Lactose as a Model Compound for Valorization of Dairy Industry Effluents. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2015, 54, 9296–9306. 10.1021/acs.iecr.5b02603. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chuntanapum A.; Matsumura Y. Char Formation Mechanism in Supercritical Water Gasification Process: A Study of Model Compounds. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2010, 49, 4055–4062. 10.1021/ie901346h. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yong T. L.-K.; Yukihiko M. Kinetic Analysis of Guaiacol Conversion in Sub- and Supercritical Water. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2013, 52, 9048–9059. 10.1021/ie4009748. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Changsuwan P.; Paksung N.; Inoue S.; Inoue T.; Kawai Y.; Noguchi T.; Tanigawa H.; Matsumura Y. Conversion of guaiacol in supercritical water gasification: Detailed effect of feedstock concentration. J. Supercrit. Fluids 2018, 142, 32–37. 10.1016/j.supflu.2018.05.024. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Promdej C.; Matsumura Y. Temperature Effect on Hydrothermal Decomposition of Glucose in Sub- And Supercritical Water. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2011, 50, 8492–8497. 10.1021/ie200298c. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Afifi A. I.; Hindermann J. P.; Chornet E.; Overend R. P. The cleavage of the aryl—O—CH3 bond using anisole as a model compound. Fuel 1989, 68, 498–504. 10.1016/0016-2361(89)90273-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vuori A. I.; Bredenberg J. B. s Thermal chemistry pathways of substituted anisoles. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 1987, 26, 359–365. 10.1021/ie00062a031. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Asmadi M.; Kawamoto H.; Saka S. Thermal reactions of guaiacol and syringol as lignin model aromatic nuclei. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrolysis 2011, 92, 88–98. 10.1016/j.jaap.2011.04.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dorrestijn E.; Mulder P. The radical-induced decomposition of 2-methoxyphenol. J. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans. 2 1999, 777–780. 10.1039/a809619h. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Scheer A. M.; Mukarakate C.; Robichaud D. J.; Nimlos M. R.; Ellison G. B. Thermal Decomposition Mechanisms of the Methoxyphenols: Formation of Phenol, Cyclopentadienone, Vinylacetylene, and Acetylene. J. Phys. Chem. A 2011, 115, 13381–13389. 10.1021/jp2068073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsumura Y.; Goto S.; Takase Y.; Inoue S.; Inoue T.; Kawai Y.; Noguchi T.; Tanigawa H. Suppression of Radical Char Production in Supercritical Water Gasification by Addition of Organic Acid Radical Scavenger. Energy Fuels 2018, 32, 9568–9571. 10.1021/acs.energyfuels.8b02063. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gutiérrez Ortiz F. J.; Campanario F. J.; Ollero P. Supercritical water reforming of model compounds of bio-oil aqueous phase: Acetic acid, acetol, butanol and glucose. Chem. Eng. J. 2016, 298, 243–258. 10.1016/j.cej.2016.04.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Blake P. G.; Jackson G. E. The thermal decomposition of acetic acid. J. Chem. Soc. B 1968, 1153–1155. 10.1039/j29680001153. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Blake P. G.; Jackson G. E. High- and low-temperature mechanisms in the thermal decomposition of acetic acid. J. Chem. Soc. B 1969, 94–96. 10.1039/j29690000094. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen M. T.; Sengupta D.; Raspoet G.; Vanquickenborne L. G. Theoretical Study of the Thermal Decomposition of Acetic Acid: Decarboxylation Versus Dehydration. J. Phys. Chem. 1995, 99, 11883–11888. 10.1021/j100031a015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Duan X.; Page M. Theoretical Investigation of Competing Mechanisms in the Thermal Unimolecular Decomposition of Acetic Acid and the Hydration Reaction of Ketene. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1995, 117, 5114–5119. 10.1021/ja00123a013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Moreira I. de P. R. Performance of simplified G2 model chemistry approaches in the study of unimolecular mechanisms: thermal decomposition of acetic acid in gas phase. J. Mol. Struct.: THEOCHEM 1999, 466, 119–126. 10.1016/S0166-1280(98)00366-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Verma A. M.; Nanda K. Kinetics of Decomposition Reactions of Acetic Acid Using DFT Approach. Open Chem. Eng. J. 2018, 12, 14–23. 10.2174/1874123101812010014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hossain M. A.; Jewaratnam J.; Ramalingam A.; Sahu J. N.; Ganesan P. A DFT method analysis for formation of hydrogen rich gas from acetic acid by steam reforming process. Fuel 2018, 212, 49–60. 10.1016/j.fuel.2017.09.098. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li A.; Lui H.-L.; Wang H.; Xu H.-b.; Jin L.-F.; Liu J.-L.; Hu J.-H. Effect of Temperature and Heating Rate on the Characteristics of Molded Biochar. BioResources 2016, 11, 3259–3274. 10.15376/biores.11.2.3259-3274. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Debiagi P. E. A.; Gentile G.; Cuoci A.; Frassoldati A.; Ranzi E.; Faravelli T. Yield, Composition and Active Surface Area of Char from Biomass Pyrolysis. Chem. Eng. Trans. 2018, 65, 97–102. 10.3303/CET1865017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]