Abstract

The bonding performance of a glycerol phosphate dimethacrylate (GPDM)-based, two-step, self-etch (SE) adhesive was experimentally compared to that of 10-methacryloyloxydecyl dihydrogen phosphate (MDP)-based universal adhesives in different application modes for enamel bonding. Microtensile bond strength (μTBS) for adhesives bonded to enamel was measured initially (24 h water storage) and after 10 000 thermocycles plus water storage for 30 days. A GPDM-based, two-bottle, two-step, self-etch adhesive (Optibond Versa, OV) and three one-bottle MDP-based universal adhesives, one self-etching (Tetric N Bond Universal, TNBU) and two with etch-and-rinse (E&R) processing (Single Bond Universal (SBU); Clearfil Universal Bond Quick (CUBQ)), were tested. Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) evaluated nanoleakage at the bonding interfaces. A profilometer determined roughnesses of enamel surfaces after phosphoric acid etching, OV priming, or TNBU conditioning. SEM observed the corresponding surface morphology. NMR and X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) characterized chemical bonding in hydroxyapatites (HAps) conditioned with the adhesives. Etch-and-rinse samples had significantly stronger bonding than self-etch samples (p < 0.05) irrespective of aging. The μTBS values for initial and aged OV were significantly higher than those of TNBU (p < 0.05). Aging did not significantly decrease μTBS for any sample except TNBU (p < 0.05), but it significantly aggravated nanoleakage. Etch-and-rinse processing resulted in less nanoleakage than self-etching; the OV samples leaked less than TNBU, both before and after aging. Phosphoric acid etching achieved the highest enamel surface roughness, followed by OV primer. Ca–O–P bonds in hydroxyapatite conditioned with TNBU, SBU, and CUBQ were confirmed by NMR, which showed similar results to XPS observations of conditioned hydroxyapatite powders except OV primer. The GPDM-based, two-step, self-etch adhesive can provide higher micromechanical retention potential, bond strength, and durability than the MDP-based universal adhesive in self-etch mode but lower performance than the MDP-based universal adhesive in etch-and-rinse mode. None of the tested adhesives could avoid nanoleakage after aging.

1. Introduction

Acid etching and the development of acidic functional monomers facilitate the strong bonding of resin cement to teeth; combined with its advantages of good edge sealing and color matching, it has become the preferred material for bonding all-ceramic restorations.1 Enamel bonding provides almost all of the required retention forces for ceramic restorations involving missing or lacking retention, especially in ceramic veneers, because minimal preparation, limited to the enamel, is always the aim during ceramic veneer preparation.

Enamel can obtain more-durable bonding than dentin2−4 owing to its higher proportion of inorganic matter.5 Similar to dentin bonding systems, the commonly used enamel bonding systems are classified as either etch-and-rinse (E&R) or self-etch (SE) according to their bonding mechanism and strategy, with E&R being more common.6 Traditional enamel–resin E&R bonding achieves adhesive force through the interlocking of the acid-etched enamel prisms and the hydroxyapatite (HAp) crystal structure and infiltrated (and subsequently polymerized) resin tags.7,8 However, the multistep preparation procedure is time-consuming, the acid etching has time-dependent effects, and the strong acidity can potentially irritate dental pulp.2 Accidental exposure to gingival tissue by etchants has also been found to cause bleeding and increased gingival crevicular fluid exudation, which, in turn, increases technique sensitivity and undermines bonding quality.2 The simpler procedure offered by SE bonding does not need a separate etching step, avoiding the risks of contaminating blood and gingival crevicular fluid caused by exposure to etchants; it therefore reduces sensitivity and clinical operation time, making it an attractive alternative to E&R bonding.9,10

Micromechanical retention between the roughened enamel surface and resin tags is still necessary for SE adhesives.11,12 The embraced acidic monomers partially demineralize the enamel surface, partially dissolve crystalline HAp, and chemically combine with the remaining crystal.13 Commercially available enamel SE adhesives can be divided into four types based on the pH of the SE solutions: “ultramild” (pH > 2.5), “mild” (pH ≈ 2), “intermediately strong” (pH ≈ 1–2), and “strong” (pH ≤ 1).3,14 However, even the most acidic SE adhesives are considered to be much less acidic than 35% phosphoric acid15 (usually around pH 0.21).9 Therefore, the ability of SE adhesives to etch enamel is not sufficient to obtain a typical resin tags structure similar to E&R adhesives. The resulting comparatively lower micromechanical retention3,16 has brought into question the durability of bonding between SE adhesives and enamel.17,18 Reviews and meta-analyses have identified drastic variation in the actual bonding properties of SE adhesives, depending on their composition and properties, especially the acidic functional monomers and pH; bond strength and durability therefore appear to be highly product-dependent.19,20

Many of today’s universal adhesives incorporate the functional phosphate ester monomer 10-methacryloyloxydecyl dihydrogen phosphate (MDP), which is considered one of the most effective monomers for strong binding to HAp.21 Another functional phosphate ester monomer that has been used in dental adhesives is glycerol phosphate dimethacrylate (GPDM), which has been utilized in E&R adhesives, SE adhesives, and self-adhesive composite cements. It is presumed that the higher etching efficacy of GPDM-based SE adhesives may result in equally effective bonding compared to phosphoric acid etching.22

Based on the above background, this study investigated four enamel bonding systems for ceramic veneers to evaluate the enamel bonding performance of GPDM-based, two-step, SE adhesive compared to three MDP-based universal adhesives in different processing modes. The bond strength and durability were tested, and the surface roughness and morphology of the treated enamel were evaluated. Nanoleakage at the bonding interface was also compared, and the chemical bonds were evaluated by NMR and X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) to explain the observed differences in bonding performance. The null hypotheses tested were (i) the GPDM-based, two-step, SE adhesive provides similar enamel bonding performance and nanoleakage to MDP-based universal adhesives in different modes and (ii) they can achieve similar chemical affinity with enamel.

2. Results

2.1. Microtensile Bond Strength (μTBS) Test and Fracture Mode Analysis

Means and standard deviations (SDs) of the μTBS results for Optibond Versa (OV), Tetric N Bond Universal (TNBU), Single Bond Universal (SBU), and Clearfil Universal Bond Quick (CUBQ) are shown in Table 1. Two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) revealed that μTBS was significantly affected by the surface treatment and aging factors (p < 0.001), while no significant interactions were noted between them (p = 1.000).

Table 1. Microtensile Bond Strengths Obtained After 24 h Water Storage or 10 000 Thermocycles Plus Water Storage for 30 Daysa.

| μTBS

(MPa)/(24 h water storage) |

μTBS

(MPa)/(10 000 thermocycles plus 30 days in water) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| groups | mean ± SD | confidence interval (95%) | mean ± SD | confidence interval (95%) |

| OV | 32.68 ± 4.05b | 30.79–34.58 | 29.97 ± 4.68B | 27.77–32.16 |

| TNBU | 27.87 ± 4.02c* | 25.99–29.75 | 25.25 ± 3.56C* | 23.58–26.92 |

| SBU | 43.39 ± 4.23a | 41.41–45.36 | 40.64 ± 5.02A | 38.29–42.99 |

| CUBQ | 43.94 ± 5.20a | 41.51–46.37 | 41.30 ± 5.38A | 38.78–43.81 |

Values with different superscript lowercase letters (24 h water storage) and uppercase letters (10 000 thermocycles plus 30 days in water) are significantly different (p < 0.05), *μ-TBS values are significantly different between 24 h water storage and after aging (p <0.05).

Tukey’s post hoc least significant difference (LSD) tests showed that the μTBS of OV, SBU, and CUBQ groups were not significantly affected by aging (p = 0.057, 0.069, and 0.122, respectively). In contrast, the μTBS of TNBU did decrease significantly after aging (p = 0.035).

The μTBS values for both E&R groups were significantly higher than those for the SE groups before and after aging (p < 0.001). Consider the SE samples: the μTBS of OV was significantly higher than that of TNBU before and after aging (p = 0.001 and 0.002, respectively). In the E&R mode, there was no significant difference in μTBS between groups CUBQ and SBU before and after aging p = 0.691 and 0.662, respectively.

Figure 1 displays the distribution of failure modes for the four groups of samples. Aging did not obviously change the distribution for each group, except that the occurrence of bonding interface failure increased after 10 000 thermocycles plus water storage for 30 days.

Figure 1.

Failure modes observed in samples employing Optibond Versa (OV), Tetric N Bond Universal (TNBU, self-etched), Single Bond Universal (SBU, etch-and-rinsed), and Clearfil Universal Bond Quick (CUBQ, etch-and-rinsed) after 24 h of water storage and after 10 000 thermocycles plus water storage for 30 days.

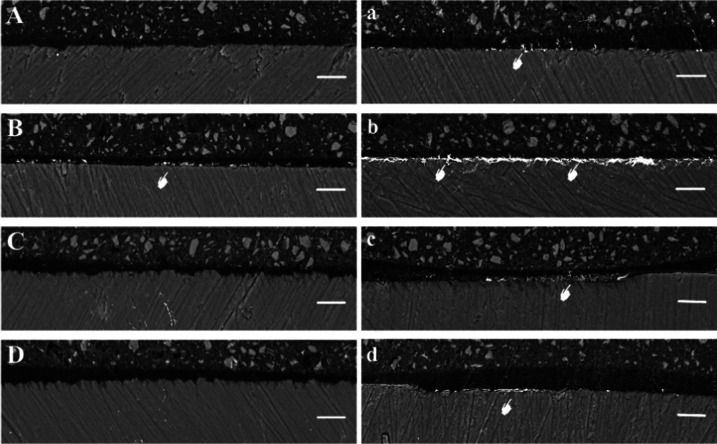

2.2. Nanoleakage Evaluation

Figures 2 and 3 show representative images of silver leakage at the resin–enamel interface after 24 h water storage and 10 000 thermocycles plus water storage for 30 days. The degree of nanoleakage in the E&R adhesives was less than that in the SE adhesives, and it increased after aging, while the OV sample leaked less than the TNBU group before and after aging. After 24 h water storage, the OV, SBU, and CUBQ groups showed almost no silver deposition, while there was discontinuous silver spotting along the bonding interface in the TNBU group. After aging, silver deposition in all four groups clearly increased. The OV group showed silver spotting along the bonding interface, while the nanoleakage was greatest in the TNBU group, which had continuous deposition of silver flakes along the bonding interface, occupying almost the whole interface. Discontinuous silver depositions occurred along the bonding interface in the SBU and CUBQ samples, appearing flocculent in the former.

Figure 2.

Representative backscattered scanning electron microscopy (SEM) micrographs of the resin–enamel interfaces after 24 h water storage (left) and after 10 000 thermocycles plus water storage for 30 days for samples (right): (A, a) Optibond Versa, (B, b) Tetric N Bond Universal, (C, c) Single Bond Universal, and (D, d) Clearfil Universal Bond Quick. In (B), the white pointer points to areas of silver deposition at the Tetric N Bond Universal–enamel interface. In the images for aged samples, the white pointers point to silver nitrate deposits in all groups, mainly within the adhesive layer. Aging consistently increased silver deposition, which was most pronounced for Tetric N Bond Universal (b) (original magnification, 1000×).

Figure 3.

Representative backscattered SEM micrographs of the resin–enamel interface after 24 h water storage (left) and after 10 000 thermocycles plus 30 days in water (right): (A, a) Optibond Versa, (B, b) Tetric N Bond Universal, (C, c) Single Bond Universal, and (D, d) Clearfil Universal Bond Quick. Aging increased silver deposition in all groups, especially Tetric N Bond Universal (original magnification, 5,000×). A: adhesive layer; E: enamel.

2.3. Morphological Observation and Roughness Evaluation of Enamel Surface after Treatment

The representative SEM images of the variously treated enamel surfaces are shown in Figure 4. Polishing with 600 grit silicon carbide paper resulted in a highly flattened pattern with clear scratches on the enamel surface (Figure 4A). Etching with phosphoric acid for 15 s left a distinct honeycomb pattern on the enamel surface owing to preferential dissolution of enamel prisms (Figure 4B). Obvious enamel-prism contours were observed on the OV group surfaces treated with primer (Figure 4C). The TNBU group showed no obvious enamel-prism etching, but did show clear scratches (Figure 4D). Figure 4E shows local high-power field observation of the crystal morphology and voids after phosphoric acid etching.

Figure 4.

SEM photomicrographs of (A) untreated enamel and enamel surfaces treated with (B) phosphoric acid, (C) Optibond Versa primer, (D) Tetric N Bond Universal adhesive, and (E) local high magnification of crystal morphology and voids after phosphoric acid etching. The white pointers indicate exposed enamel-prism contours. (Original magnification: main images (A–D), 2000×; insets (a–d), 10 000×; (E), 60 000×.).

Figure 5 presents typical three-dimensional (3D) images of enamel surfaces that had been polished with 600 grit silicon carbide paper, etched with phosphoric acid, and conditioned with OV primer and TNBU. The mean Ra and SDs are presented in Table 2.

Figure 5.

Representative 3D images of (A) untreated enamel and enamel surfaces treated with (B) phosphoric acid, (C) Optibond Versa primer, and (D) Tetric N Bond Universal.

Table 2. Mean and Standard Deviation Surface Roughness of Untreated Enamel (Ctr) and Enamel Treated with Phosphoric Acid (Etch), Optibond Versa Primer (OV), and Tetric N Bond Universal Adhesive (TNBU)a.

| surface

roughness (μm) |

||

|---|---|---|

| sample group | mean ± SD | confidence interval (95%) |

| Ctr | 1.356 ± 0.223d | 1.214–1.498 |

| Etch | 2.062 ± 0.180a | 1.948–2.177 |

| OV | 1.821 ± 0.202b | 1.693–1.949 |

| TNBU | 1.639 ± 0.184c | 1.522–1.756 |

Values with different superscript lowercase letters are significantly different (p < 0.05).

ANOVA and post hoc (LSD) testing showed that the Ra was greatest after phosphoric acid etching and lowest in the control. The Ra of the acid-etched enamel was significantly higher than that of the control, OV, and TNBU groups (p < 0.001, p = 0.005, and p < 0.001, respectively). The Ra of the OV group was significantly higher than that of the TNBU group (p = 0.030), and both groups were significantly rougher than the control group (p < 0.001 and p = 0.001, respectively).

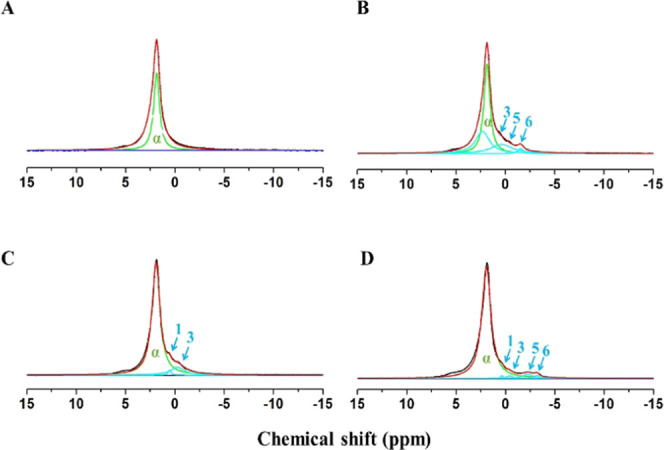

2.4. NMR and XPS Analyses

Based on a previous study,23 the 31P NMR peaks detected in each HAp powder sample were assigned as listed in Table 3. Figure 6 shows the typical 31P NMR spectra of HAp powder reactants treated with the four commercial adhesives. The OV samples did not form the typical 31P NMR peak like the other three groups. The 31P NMR peak for HAp is labeled α. The newly developed 31P NMR peaks labeled 1, 3, 5, and 6 were assigned to four types of MDP-Ca salt, namely, the di-calcium salt of the MDP monomer (DCS-MM), the di-calcium salt of the MDP dimer (DCS-MD), the mono-calcium salt of the MDP monomer (MCS-MM), and the mono-calcium salt of the MDP dimer (MCS-MD), respectively. CUBQ predominantly developed peaks 1, 3, 5, and 6; TNBU predominantly developed peaks 3, 5, and 6; and SBU predominantly developed peaks 1 and 3.

Table 3. Chemical Structures of Four Types of MDP-Ca Salt Detected after HAp Powder Reactions.

Figure 6.

Typical 31P NMR spectra of HAp reacted with four commercial adhesives: (A) Optibond Versa primer, (B) Tetric N Bond Universal, (C) Single Bond Universal, and (D) Clearfil Universal Bond Quick. The arrows denote the NMR peaks assigned to the phosphorus atoms of the MDP-Ca salts. Peak α was assigned to HAp. The numbered peaks were assigned to the phosphorus atoms in the corresponding salts in Table 3.

Based on the NMR analysis results, Figure 7 shows curve-fitting results for the 31P NMR spectra of the groups of HAp powder samples. The simulated spectra include each of the peaks α, 1, 3, 5, and 6 that were experimentally observed.

Figure 7.

Curve-fitting corresponding to observed 31P NMR spectra (black lines) for HAp reacted with (A) Optibond Versa primer, (B) Tetric N Bond Universal, (C) Single Bond Universal, and (D) Clearfil Universal Bond Quick. The green lines show the simulated α peak for HAp. The sky blue lines are the simulated peaks 1, 3, 5, and 6 for the four MDP-Ca salts. The red line is the resulting overall synthetic spectrum.

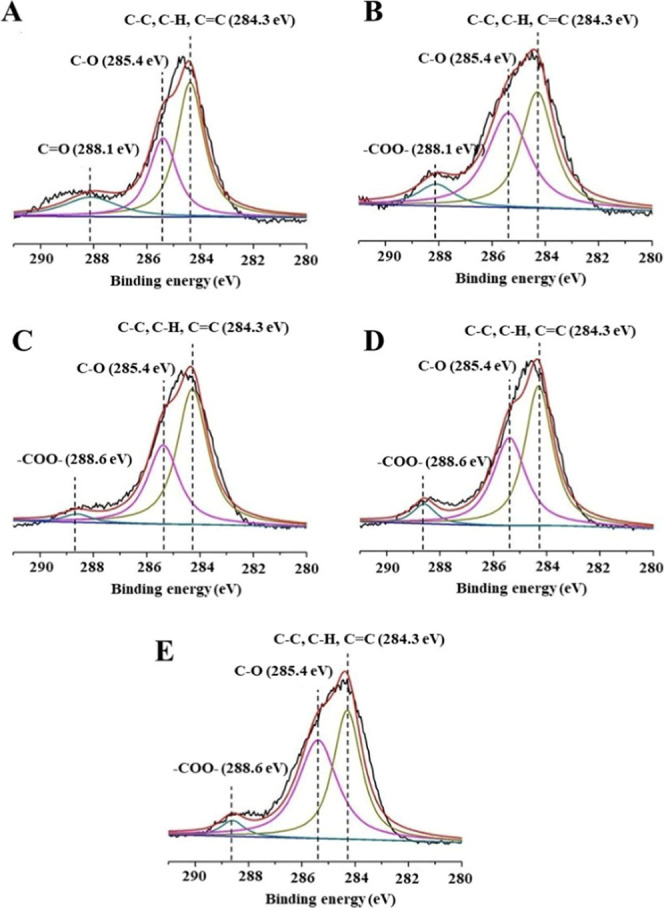

The wide-scan XPS spectra of HAp powders treated with four adhesives are shown in Figure 8. Compared to the peak intensity (C 1s) of the untreated and OV primer-conditioned powders, the peak intensities of the TNBU-, SBU-, and CUBQ-treated HAp samples significantly increased. Narrow-scan spectra of the reacted HAp powder samples are shown in Figure 9. The C 1s region of untreated HAp powder revealed a backbone (C–C, C–H, and C=C) peak at 284.3 eV, a C–O peak at 285.4 eV, and a C=O peak at 288.1 eV (Figure 9A). The C 1s region of OV primer-conditioned samples revealed a backbone (C–C, C–H, and C=C) peak at 284.3 eV, a C–O peak at 285.4 eV, and a −COO– peak at 288.1 eV (Figure 9B). The C 1s regions for TNBU-, SBU-, and CUBQ-treated samples were similar, revealing a backbone (C–C, C–H, and C=C) peak at 284.3 eV, a C–O peak at 285.4 eV, and a −COO– peak at 288.6 eV (Figure 9C–E).

Figure 8.

Wide-scan XPS spectra of (A) untreated HAp powder and HAp powder conditioned with (B) Optibond Versa primer, (C) Tetric N Bond Universal, (D) Single Bond Universal, and (E) Clearfil Universal Bond Quick. (A, B) present very similar C 1s peak intensities, while those of (C–E) are significantly increased.

Figure 9.

Narrow-scan C 1s XPS spectra. (A) Untreated HAp powder revealed a peak at 284.3 eV representing backbone (C–C, C–H, and C=C) bindings, a peak at 285.4 eV representing C–O binding, and a peak at 288.1 eV representing C=O binding. (B) HAp treated with Optibond Versa primer showed peaks at 284.3 eV (backbone C–C, C–H, and C=C bindings), 285.4 eV (C–O binding), and 288.1 eV (−COO– binding). HAp treated with (C) Tetric N Bond Universal, (D) Single Bond Universal, and (E) Clearfil Universal Bond Quick each showed similar peaks at 284.3 eV (backbone C–C, C–H, and C=C bindings), 285.4 eV (C–O binding), and 288.6 eV (−COO– binding).

3. Discussion

Adhesion to enamel is generally considered less challenging than to dentin; the adhesion mainly relies on micromechanical interlocking of the resin matrix with exposed enamel prisms.8 SEM revealed a clear honeycomb structure, similar to the tentacle-like surface texture of a sea anemone, on the enamel surface etched with 35% phosphoric acid and rinsed. This structure was confined to the enamel matrix in a tight arrangement that included ridges and gaps, which made an ideal structure for resin matrix infiltration to form tags for strong microlocking.

Universal adhesive is a promising material for bonding to enamel as well as to dentin; therefore, we selected three enamel adhesives suitable for ceramic veneer bonding in the present study. Previous studies have confirmed that only strong SE adhesives with pH ≤ 1 can form typical resin tags on enamel and resin matrices, while mild and ultramild SE adhesives have difficulty forming typical roughened structures.24 OV is a representative, two-step, commercially available, SE enamel adhesive. Its functional monomer, GPDM, with a pH as low as 1.6, has led to OV being claimed as capable of achieving as high a bonding performance as E&R adhesives. Further advantages are simple SE operation and strong micromechanical retention and auxiliary chemical bonding. The SEM images showed that in contrast to the typical honeycomb pattern exposed on an enamel surface by phosphoric acid etching, the OV primer instead induced clearly shallower scratches on the enamel surface. The enamel-prism contours were exposed with visible enamel-prism boundaries, suggesting that the pH of 1.6 in the OV primer still produced an intaglio surface morphology to facilitate micromechanical intercalation force. Different from conventionally etched enamel, unchanged scratches were observable on the enamel surface treated by the MDP-based universal adhesive TNBU, indicating that etching at its pH 2.5–3.0 was insufficient to carve the enamel.25 The SEM images of SBU and CUBQ in SE mode were similar to those of TNBU, which may be attributed to all three universal adhesives having similar pH values. They also showed weaker enamel etching ability than OV, suggesting that the subsequent micromechanical retention forces were also weaker than that of OV.

The thicknesses of the smear layers generated with 600 grit and 4000 grit silicon carbide paper correspond approximately to those generated with a fine and extrafine diamond bur, respectively.26 In clinical practice, the preparation of teeth for ceramic veneer involves refining and polishing with a fine diamond bur. Therefore, to replicate its effect, we selected 600 grit silicon carbide paper to prepare standardized surfaces for bond performance testing.

The measured surface roughness matched the SEM observation well. The enamel surface etched with phosphoric acid had a significantly higher Ra than the surfaces conditioned with GPDM-based two-step SE adhesives and MDP-based universal adhesives in SE mode, and the two-step SE adhesive achieved a significantly rougher surface than the universal adhesives in SE mode. Both the SEM and surface roughness results suggest that the lower the pH, the stronger the etching ability and the higher the obtained surface roughness.27 Higher surface roughness usually obtains strong bonding through the contribution of micromechanical retention.28,29 In the present study, μTBS values for the MDP-based universal adhesives in E&R processing were significantly higher than those for MDP-based universal adhesives in SE mode and GPDM-based two-step SE adhesive regardless of aging. Moreover, the μTBS values for initial and aged GPDM-based two-step SE adhesive were significantly higher than those for MDP-based universal adhesives in SE mode, consistent with the literature.30 The present fracture mode analysis also showed higher occurrence of interface failure in both SE groups, consistent with these samples’ lower μTBS compared with the E&R samples.

SE adhesives are reported to benefit from additional chemical interactions of their functional monomers with HAp.9 The adhesion/decalcification concept (“AD-concept”) has been advanced to explain the interaction of acidic functional monomers with HAp.9,31 After the electrostatic binding of the functional monomer to calcium ions in the HAp crystal, calcium ions and/or phosphate ions are released in proportion to form monomer–Ca salts.32 The resin bond strength of enamel has been reported to depend partially on the amount of these functional salts produced.33 The chemical reaction to form MDP-Ca salts through the interaction of MDP and HAp can be expressed as follows9

| 1 |

(R = MDP)

| 2 |

Three universal adhesives used here (TNBU, SBU, and CUBQ) contained MDP, one of the most effective functional monomers that can combine with HAp.21 The present NMR observations detected Ca–O–P bonds in HAp conditioned by TNBU, SBU, and CUBQ, but not in HAp conditioned by OV primer, suggesting MDP-Ca salts formed. However, while MDP-Ca salts were detected by NMR, GPDM-Ca salts were not, probably due to the higher solubility of the latter. Previous studies have confirmed the chemical bonds between phosphate ester monomers and HAp.34−36 The present wide-scan XPS spectra showed that the C 1s peak intensity of HAp significantly increased after treatment with TNBU, SBU, or CUBQ adhesive, but not with OV primer, indicating that carbon chain fragments of adhesives adhered to the HAp. The narrow-scan C 1s spectra are consistent with the literature,36 suggesting the presence of a chemical affinity layer in the HAp. SEM observation also showed that some of the enamel prisms were obscured, possibly by monomer calcium salt deposition in the TNBU group. The enamel-prism contours appeared more prominently in the OV priming samples, with hardly any monomer calcium deposition compared to TNBU conditioning, consistent with the NMR results. The above analysis shows that the second hypothesis, that GPDM-based, two-step, SE adhesive can achieve similar chemical affinity to MDP-based universal adhesives, can be rejected.

Figure 10 illustrates the chemisorption mechanism of GPDM and MDP with HAp. Although MDP has stronger chemical affinity with calcium ions than GPDM, due to the increase of enamel-prism demineralization and HAp dissolution and the full infiltration of the resin matrix into the exposed enamel-prism structure,22 the μTBS of samples treated with OV containing GPDM was significantly higher than that of those treated with TNBU containing MDP. This indicates that the chemical binding force resulting from the chemical affinity between the functional monomers and HAp contributed less to the overall enamel–resin bond strength than micromechanical retention.

Figure 10.

Chemisorption mechanisms of GPDM and MDP on HAp.

Generally, universal adhesives used in SE processing may not be able to bond as strongly with enamel as E&R adhesives, but their bond strengths have been reported to be acceptable,37,38 and our results confirmed this. However, the main cause of clinical failure of restorations is loss of adhesion and/or destruction of edge seal;39 therefore, the durability of the material is a more important indicator of bonding performance. For dentin bonding, the dentin’s collagen fibers provide the main source of bonding force, and the reduced long-term bond durability caused by collagen degradation is the main problem of dentin bonding.40 Therefore, the activation of metalloproteinases in dentin and the subsequent degradation of collagen or hybrid layer is the main index for evaluation the bonding durability of dentin, which makes long-term water storage a valuable artificial aging technique.41 Enamel comprises up to 96% inorganic substances; therefore, thermal stress might induce much greater damage around an adhesive layer on enamel than hydrolytic degradation, and thermocycling is thus recommended to simulate in vivo aging. The use of 10 000 thermal cycles has been suggested to correspond to approximately 1 year of in vivo functioning.42 Differences in the thermal expansion moduli of the resin and enamel will lead thermal stress to cause cracks at their bonding interface, destroying the poorly polymerized oligomers.39,43 During the residence time, water permeates into the bonding interface, resulting in the expansion and plasticization of the bonded resin. Water also accelerates the hydrolysis of the resin, resulting in nanoleakage, destroying the bonding interface, and reducing the mechanical properties.

In the present study, 10 000 thermocycles plus 30 days in water decreased the μTBS of the TNBU samples, but not the other three groups. Fracture mode analysis gave more-detailed results, as bond interface failure became more prevalent in all of the groups after aging, suggesting that thermal stress damage to the bond interface decreased the mechanical properties.39 Universal adhesives in E&R processing and two-step SE adhesive presented significantly better bonding durability and decreased nanoleakage than the universal adhesives in SE processing. This was possibly due to the cured adhesive layer in SE adhesive acting as a semi-permeable membrane, allowing water transport from the enamel to the mixed zone between the adhesive and the uncured resin material, resulting in osmotic blistering at the bonding interface.44 Water inevitably remaining at the enamel surface will inhibit optimal copolymerization of the acidic monomers. This will reduce the edge integrity of the adhesives and allow edge leakage that affects the durability of the bonding.45 In contrast, less silver deposition was found in E&R mode and for two-step SE adhesive, possibly due to the penetration of resin monomers into the etched enamel surface; this would encapsulate the crystal structure, provide an effective seal, and protect the outermost enamel.

Enamel HAp has been reported to have higher crystallinity and less crisscross orientation than dentinal HAp. This would reduce both the binding ability of functional monomers to calcium ions in enamel and the amount of monomer–Ca salts produced.46,47 Therefore, adhesion to enamel in SE mode remains challenging.

The hydrophilic nature of the primers or adhesives caused nanoleakage in the bonding layer to be time-dependent.48−50 The present study found the degree of nanoleakage in GPDM-based, two-step, SE samples (with OV) to be similar to those of MDP-based, universal adhesives in E&R mode (SBU and CUBQ). In contrast, nanoleakage in the MDP-based universal adhesives in SE mode (TNBU) was much more serious, especially after aging: continuous depositions of silver flakes occurred across almost the whole bonding interface. Furthermore, the μTBS, nanoleakage and bonding durability of the TNBU samples before and after aging were the worst among the four groups for the reasons mentioned above. To compensate for the shortcomings of SE adhesive, some reports recommend additional etching with phosphoric acid or hydrophobic adhesive to enhance bonding durability and improve the enamel surface roughness.29,51 However, as nanoleakage is a manifestation of the inability of contemporary adhesives to repel free water,49 even the smallest degree will eventually lead to leakage at the bonding interfaces and the initiation of bonding failure.

The results for bond strength, bonding durability and nanoleakage indicate that the first hypothesis, that GPDM-based, two-step, SE adhesive provides similar enamel bonding and nanoleakage performance to MDP-based universal adhesive in different modes can be rejected. The bonding durability and nanoleakage results suggest that the chemical affinity of functional monomers to HAp had a minor role in overall enamel bonding performance in comparison to micromechanical retention.

4. Conclusions

This work’s results and analyses lead to the following conclusions:

-

(1)

GPDM-based, two-step, SE adhesive created rougher enamel surfaces than MDP-based universal adhesive in SE mode, resulting in stronger and more durable enamel bonding.

-

(2)

GPDM-based, two-step, SE adhesive and MDP-based universal adhesives applied in different modes can provide clinically acceptable bond strengths. While none could avoid nanoleakage after aging, it was more serious in the samples with universal adhesive in SE mode.

5. Materials and Methods

5.1. Preparation of Enamel Specimens

With the approval of the Ethical Committee Department, Affiliated Hospital of Stomatology, Nanjing Medical University (file number PJ2019-054-001), 98 freshly extracted caries-free human third molars were collected and stored in Hanks balanced salt solution at 4 °C and used within 1 month. The teeth were separated along the cementoenamel junction using a low-speed diamond saw (Isomet, Buehler, LakeBluff, IL) in a running water-cooled state, and all roots were removed. The crowns were cut in the mesio-distal direction along the long axis of the tooth, and 196 enamel samples were obtained. The range from 0.5 mm above the buccal–lingual cementoenamel junction to 2 mm below the dental cusp was taken as the experimental site, and the enamel surfaces were wet-polished with 600 grit silicon carbide paper for 1 min to obtain a flat and freshly exposed enamel surface. All enamel surfaces were carefully verified for the absence of dentin using a stereo-microscope (SMZ1000, Nikon, Japan).

5.2. Microtensile Bond Strength (μTBS) Testing and Fracture Mode Analysis

A total of 120 enamel samples were randomly selected and divided into groups of 30 to test the following four enamel bonding systems applied for bonding ceramic veneers: a GPDM-based two-step SE adhesive, Optibond Versa (OV; Kerr, Orange, CA); an MDP-based universal adhesive Tetric N Bond Universal (TNBU; Ivoclar Vivadent, Schaan, Liechtenstein) used in SE mode; two MDP-based universal adhesives, Single Bond Universal (SBU; 3M ESPE St. Paul, MN) and Clearfil Universal Bond Quick (CUBQ; Kuraray Noritake, Tokyo, Japan) used in E&R mode. Table 4 lists the components of the adhesives and bonding was applied following each manufacturer’s instructions (Table 5).

Table 4. Manufacturers and Components of the Commercial Adhesive Systems Used in this Studya.

| brand name | manufacturer | lot number | composition (from manufacturer) | pH |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Optibond Versa (OV) | Kerr, Orange, CA | primer: 7078235 | primer: GPDM, HEMA, dimethacrylate, camphorquinone, water, ethanol, acetone | 1.6 |

| adhesive: 7103795 | adhesive: Bis-GMA, HEMA, trifunctional monomer, ethanol, camphorquinone, barium glass filler, fluoridecontaining filler, nanofiller | |||

| Tetric N Bond Universal (TNBU) | Ivoclar Vivadent, Schaan, Liechtenstein | Y20609 | HEMA, D3MA, Bis-GMA, MDP, MCAP, ethanol, water, silicon dioxide filler, camphorquinone, stabilizers | 2.5–3.0 |

| Single Bond Universal (SBU) | 3M ESPE(St. Paul, MN) | 90403A | MDP, Bis-GMA, HEMA, methacrylate resins, silane methacrylate-modified polyalkenoic acid copolymer, filler, ethanol, water, camphorquinone | 2.7 |

| Clearfil Universal Bond Quick (CUBQ) | Kuraray, Noritake Dental, Tokyo, Japan | 9L0048 | MDP, Bis-GMA, HEMA, hydrophilic amide monomer, colloidal silica, ethanol, camphorquinone, accelerators, water, sodium fluoride | 2.3 |

Abbreviations: MDP, 10-methacryloyloxydecyl dihydrogen phosphate; Bis-GMA, bisphenol A glycidyl dimethacrylate; D3MA, decandiol dimethacrylate; GPDM, glycerol phosphate dimethacrylate; HEMA, 2-hydroxyethyl methacrylate; MCAP, methacrylated carboxylic acid polymer.

Table 5. Application Protocols for Each Adhesive.

| sample group | application technique following the respective manufacturer’s instructions |

|---|---|

| OV | apply Optibond Versa primer for 20 s, gently air-dry for 5 s, then apply Optibond Versa adhesive for 20 s, air-thin for 15 s, light-cure for 10 s |

| TNBU | apply Tetric N Bond Universal for 20 s, air-thin for 15 s, light-cure for 10 s |

| SBU | etch with 35% phosphoric acid for 15 s, rinse, and air-dry to produce a frosty appearance of enamel; then, apply Single Bond Universal for 20 s, air-thin for 15 s, light-cure for 10 s |

| CUBQ | etched enamel with 35% phosphoric acid for 15 s, rinse, and air-dry to produce a frosty appearance of enamel; then, apply Clearfil Universal Bond Quick for 20 s, air-thin for 15 s, light-cure for 10 s |

Prepolymerized resin composite (Filtek Z250, 3M ESPE, St. Paul, MN) columns of a similar size (3 mm × 3 mm × 2 mm) to the exposed enamel surface were prepared using nylon molds. One resin column was placed on each of the 120 pretreated enamel surfaces using a layer of phosphate ester monomer-free resin cement (RelyX Ultimate, 3M ESPE, Seefeld, Germany; lot number, 5858822) under a constant load of 10 N. Excess cement was removed with a probe, and samples were then light-cured with a light-emitting diode (LED) lamp (1000 mW/cm2, Elipar FreeLight 2, 3M ESPE, Seefeld, Germany) at four different locations for 40 s each. Two or three layers of resin composite were placed on the oxygen-inhibited surface of each resin column, with each layer being not more than 2 mm; they were then light-cured for 20 s each. A 1 mm square was removed from each profile of the bonded enamel specimen to fully expose the bonding interface.

Half of the bonded enamel specimens for each group were stored in distilled water at 37 °C for 24 h (the initial samples); the rest were aged by 10 000 thermocycles (TC-501F, Suzhou Weier Lab ware Co. Ltd., China) comprising 30 s at 5 °C and 30 s at 55 °C, with a transition time of 3 s, plus 30 days in water at 37 °C.

Before μTBS testing, all specimens were sectioned perpendicular to the interface using a water-cooled low-speed diamond saw to obtain beam micro-specimens (1 mm × 1 mm wide; 7–8 mm long), which were tested on a microtensile tester (Bisco, Schaumburg, IL) and subjected to tensile stress at a crosshead speed of 1 mm/min. The maximum load (N) was recorded.

Fracture modes were determined under a stereo-microscope (SMZ1000, Nikon, Japan). According to the morphological characteristics of the fracture surface and the residue of the adhesive and resin cement, fracture modes were classified as “adhesive (interfacial) failure” (completely exposed enamel bonding surface with no residual resin cement), “cohesive failure in resin” (no enamel bonding surface was exposed, and fracture occurred inside the composite resin column, resin cement or dentin), or “mixed failure” (partial exposed enamel bonding surface with residual composite resin or resin cement).

After homogeneity of variance and normality tests, two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Tukey’s post hoc LSD tests evaluated the effects of surface treatment and aging factors on μTBS using the SPSS 22.0 statistical software package (IBM SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL). A threshold of p <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

5.3. Nanoleakage Evaluation

The μTBS tests also considered nanoleakage using randomly selected micro-specimens (three initial and three aged). All of the specimens were wet-polished using wet silicon carbide papers (600, 800, 1500, 2000, 3000, and 4000 grit) in turn, and coated with two layers of nail varnish applied 1 mm from the bonding interface. They were then immersed in 50 wt % ammoniacal silver nitrate solution for 24 h, rinsed thoroughly under running tap water, and exposed to a photodeveloping solution for 8 h under a fluorescent light. Each slab was then wet-polished with 1500 grit silicon carbide paper to remove the surface layer of silver. Following rinsing and air-drying, the specimens were gold-coated and examined by SEM (TESCAN, MAIA3, Kohoutovice, Czech Republic) in backscattered electron mode.

5.4. Morphological Observation and Surface Roughness of Enamel Surface after Treatments

Fifty-two 3 mm × 3 mm× 2 mm enamel samples were prepared (n = 13). Etchant, OV primer, and TNBU were used as in the μTBS test, but without light curing; untreated cut enamel was used as a control.

The treated enamel samples were ultrasonically rinsed several times alternately with acetone and deionized water to remove residual monomers. All of the enamel samples were dehydrated step by step in aqueous ethanol.

Twelve treated enamel samples for each group were randomly selected for surface roughness determination by 3D optical microscopy (contour GT-X 3D optical microscope, Bruker, Billerica, MA). The recorded surface roughness (Ra, μm) values were the average for the observation area of each sample. After tests of normal distribution and homogeneity of variance, the effects of different surface treatments on roughness were statistically analyzed using one-way ANOVA and post hoc (LSD) testing.

Another specimen for each group was gold-coated and observed by SEM in a vacuum environment with an accelerating voltage of 20 kV and a working distance of 7 mm.

5.5. NMR and XPS of HAp Samples

Suspensions of 0.2 g of HAp powder (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, MO) in each of the four adhesives were dispersed by ultrasonication for 30 min. The conditioned HAp powder was washed three times with absolute ethanol and air-dried at room temperature. NMR spectra for 31P of the reactants were recorded (AVANCE III HD 400M, Bruker, Germany) and given with the chemical shift expressed as ppm, using 85% H3PO4 as an external reference. The spectra were analyzed by Mestrenova and OriginPro 8.0 Data Analysis and Graphing Software (OriginLab Co., Northampton, MA).

HAp powders conditioned by four adhesives and an untreated control were also examined with XPS (Escalab 250xi, Thermo Fisher Scientific, U.K.) conducted using monochromatic Al Kα radiation (1486.6 eV photo energy, energy step size 0.05 eV). Narrow-scan spectra of the C 1s region were obtained and peak-fitted using XPS Peak 4.1 software, with the Lorentz–Gauss ratio (L/G ratio) fixed at 80% and a Shirley function used to subtract the background.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Mr. Taoran Ma (Kuraray Noritake Dental, Japan) for providing the Clearfil Universal Bond Quick adhesive, and thank Mr. Yan Fang (NIGPAS, China) for providing technical support in SEM observation. This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China [grant 81970927], the Natural Science Foundation of Jiangsu Province of China [BK20191348], the Qing Lan Project and the Priority Academic Program Development of Jiangsu Higher Education Institutions [grant 2018-87].

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

References

- Saker S.; Özcan M.; Al-Zordk W. The Impact of Etching Time and Material on Bond Strength of Self-Adhesive Resin Cement to Eroded Enamel. Dent. Mater. J. 2019, 38, 921–927. 10.4012/dmj.2018-126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pashley D. H.; Tay F. R.; Breschi L.; Tjäderhane L.; Carvalho R. M.; Carrilho M.; Tezvergil-Mutluay A. State of the Art Etch-and-Rinse Adhesives. Dent. Mater. 2011, 27, 1–16. 10.1016/j.dental.2010.10.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Meerbeek B.; Yoshihara K.; Yoshida Y.; Mine A.; De Munck J.; Van Landuyt K. L. State of the Art of Self-Etch Adhesives. Dent. Mater. 2011, 27, 17–28. 10.1016/j.dental.2010.10.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Latta M. A.; Tsujimoto A.; Takamizawa T.; Barkmeier W. W. Enamel and Dentin Bond Durability of Self-Adhesive Restorative Materials. J. Adhes. Dent. 2020, 22, 99–105. 10.3290/j.jad.a43996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho K.; Wang G.; Raju R.; Rajan G.; Fang J.; Stenzel M. H.; Farrar P.; Prusty B. G. Influence of Surface Treatment on the Interfacial and Mechanical Properties of Short S-Glass Fiber-Reinforced Dental Composites. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2019, 11, 32328–32338. 10.1021/acsami.9b01857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Meerbeek B.; De Munck J.; Yoshida Y.; Inoue S.; Vargas M.; Vijay P.; Van Landuyt K.; Lambrechts P.; Vanherle G. Buonocore Memorial Lecture. Adhesion to Enamel and Dentin: Current Status and Future Challenges. Oper. Dent. 2003, 28, 215–235. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Meerbeek B.; Yoshihara K.; Van Landuyt K.; Yoshida Y.; Peumans M. From Buonocore’s Pioneering Acid-Etch Technique to Self-Adhering Restoratives. A Status Perspective of Rapidly Advancing Dental Adhesive Technology. J. Adhes. Dent. 2020, 22, 7–34. 10.3290/j.jad.a43994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeda M.; Takamizawa T.; Imai A.; Suzuki T.; Tsujimoto A.; Barkmeier W. W.; Latta M. A.; Miyazaki M. Immediate Enamel Bond Strength of Universal Adhesives to Unground and Ground Surfaces in Different Etching Modes. Eur. J. Oral Sci. 2019, 127, 351–360. 10.1111/eos.12626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshihara K.; Hayakawa S.; Nagaoka N.; Okihara T.; Yoshida Y.; Van Meerbeek B. Etching Efficacy of Self-Etching Functional Monomers. J. Dent. Res. 2018, 97, 1010–1016. 10.1177/0022034518763606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perdigão J.; Geraldeli S.; Hodges J. S. Total-Etch Versus Self-Etch Adhesive: Effect on Postoperative Sensitivity. J. Am. Dent. Assoc. 2003, 134, 1621–1629. 10.14219/jada.archive.2003.0109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moura S. K.; Pelizzaro A.; Dal Bianco K.; de Goes M. F.; Loguercio A. D.; Reis A.; Grande R. H. Does the Acidity of Self-Etching Primers Affect Bond Strength and Surface Morphology of Enamel?. J. Adhes. Dent. 2006, 8, 75–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loguercio A. D.; Muñoz M. A.; Luque-Martinez I.; Hass V.; Reis A.; Perdigão J. Does Active Application of Universal Adhesives to Enamel in Self-Etch Mode Improve their Performance?. J. Dent. 2015, 43, 1060–1070. 10.1016/j.jdent.2015.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nikaido T.; Takagaki T.; Sato T.; Burrow M. F.; Tagami J. The Concept of Super Enamel Formation -Relationship between Chemical Interaction and Enamel Acid-Base Resistant Zone at the Self-Etch Adhesive/Enamel Interface. Dent. Mater. J. 2020, 39, 534–538. 10.4012/dmj.2020-165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Firouzmandi M.; Khashaei S. Knoop Hardness of Self-Etch Adhesives Applied on Superficial and Deep Dentin. J. Dent. 2020, 21, 42–47. 10.30476/DENTJODS.2019.77805.0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosa W. L.; Piva E.; Silva A. F. Bond Strength of Universal Adhesives: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. J Dent. 2015, 43, 765–776. 10.1016/j.jdent.2015.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mine A.; De Munck J.; Vivan Cardoso M.; Van Landuyt K. L.; Poitevin A.; Kuboki T.; Yoshida Y.; Suzuki K.; Van Meerbeek B. Enamel-Smear Compromises Bonding by Mild Self-Etch Adhesives. J. Dent. Res. 2010, 89, 1505–1509. 10.1177/0022034510384871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osorio R.; Monticelli F.; Moreira M. A.; Osorio E.; Toledano M. Enamel-Resin Bond Durability of Self-Etch and Etch & Rinse Adhesives. Am. J. Dent. 2009, 22, 371–375. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki T.; Takamizawa T.; Barkmeier W. W.; Tsujimoto A.; Endo H.; Erickson R. L.; Latta M. A.; Miyazaki M. Influence of Etching Mode on Enamel Bond Durability of Universal Adhesive Systems. Oper. Dent. 2016, 41, 520–530. 10.2341/15-347-L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshihara K.; Yoshida Y.; Nagaoka N.; Hayakawa S.; Okihara T.; De Munck J.; Maruo Y.; Nishigawa G.; Minagi S.; Osaka A.; Van Meerbeek B. Adhesive Interfacial Interaction Affected by Different Carbon-Chain Monomers. Dent. Mater. 2013, 29, 888–897. 10.1016/j.dental.2013.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshihara K.; Yoshida Y.; Hayakawa S.; Nagaoka N.; Torii Y.; Osaka A.; Suzuki K.; Minagi S.; Van Meerbeek B.; Van Landuyt K. L. Self-Etch Monomer-Calcium Salt Deposition on Dentin. J. Dent. Res. 2011, 90, 602–606. 10.1177/0022034510397197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li M.; Xu J.; Zhang L.; Wang C.; Jin X.; Hong Y.; Fu B.; Hannig M. Effect of a Novel Prime-and-Rinse Approach on Short- and Long-term Dentin Bond Strength of Self-Etch Adhesives. Eur. J. Oral Sci. 2019, 127, 547–555. 10.1111/eos.12660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshihara K.; Nagaoka N.; Hayakawa S.; Okihara T.; Yoshida Y.; Van Meerbeek B. Chemical Interaction of Glycero-Phosphate Dimethacrylate (GPDM) with Hydroxyapatite and Dentin. Dent. Mater. 2018, 34, 1072–1081. 10.1016/j.dental.2018.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujita Nakajima K.; Aoki Tabei N.; Arita A.; Nishiyama N. NMR Study on the Demineralization Mechanism of the Enamel and Dentin Surfaces in MDP-based all-in-one Adhesive. Dent. Mater. J. 2018, 37, 693–701. 10.4012/dmj.2017-292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacker-Guhr S.; Sander J.; Luehrs A. K. How ″Universal″ is Adhesion? Shear Bond Strength of Multi-Mode Adhesives to Enamel and Dentin. J. Adhes. Dent. 2019, 21, 87–95. 10.3290/j.jad.a41974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nurrohman H.; Nikaido T.; Takagaki T.; Sadr A.; Ichinose S.; Tagami J. Apatite Crystal Protection Against Acid-Attack Beneath Resin-Dentin Interface with Four Adhesives: TEM and Crystallography Evidence. Dent. Mater. 2012, 28, e89–e98. 10.1016/j.dental.2012.04.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tani C.; Finger W. J. Effect of Smear Layer Thickness on Bond Strength Mediated by Three all-in-one Self-Etching Priming Adhesives. J. Adhes. Dent. 2002, 4, 283–289. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trevelin L. T.; Villanueva J.; Zamperini C. A.; Mathew M. T.; Matos A. B.; Bedran-Russo A. K. Investigation of Five α-hydroxy Acids for Enamel and Dentin Etching: Demineralization Depth, Resin Adhesion and Dentin Enzymatic Activity. Dent. Mater. 2019, 35, 900–908. 10.1016/j.dental.2019.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimatani Y.; Tsujimoto A.; Nojiri K.; Shiratsuchi K.; Takamizawa T.; Barkmeier W. W.; Latta M.; Miyazaki M. Reconsideration of Enamel Etching Protocols for Universal Adhesives: Effect of Etching Method and Etching Time. J. Adhes. Dent. 2019, 21, 345–354. 10.3290/j.jad.a42933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sai K.; Takamizawa T.; Imai A.; Tsujimoto A.; Ishii R.; Barkmeier W. W.; Latta M. A.; Miyazaki M. Influence of Application Time and Etching Mode of Universal Adhesives on Enamel Adhesion. J. Adhes. Dent. 2018, 20, 65–77. 10.3290/j.jad.a39913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takamizawa T.; Barkmeier W. W.; Sai K.; Tsujimoto A.; Imai A.; Erickson R. L.; Latta M. A.; Miyazaki M. Influence of Different Smear Layers on Bond Durability of Self-Etch Adhesives. Dent. Mater. 2018, 34, 246–259. 10.1016/j.dental.2017.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tian F. C.; Wang X. Y.; Huang Q.; Niu L. N.; Mitchell J.; Zhang Z. Y.; Prananik C.; Zhang L.; Chen J. H.; Breschi L.; Pashley D. H.; Tay F. R. Effect of Nanolayering of Calcium Salts of Phosphoric Acid Ester Monomers on the Durability of Resin-Dentin Bonds. Acta Biomater. 2016, 38, 190–200. 10.1016/j.actbio.2016.04.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carrilho E.; Cardoso M.; Marques Ferreira M.; Marto C. M.; Paula A.; Coelho A. S. 10-MDP Based Dental Adhesives: Adhesive Interface Characterization and Adhesive Stability-A Systematic Review. Materials 2019, 12, 790 10.3390/ma12050790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujita Nakajima K.; Nikaido T.; Francis Burrow M.; Iwasaki T.; Tanimoto Y.; Hirayama S.; Nishiyama N. Effect of the Demineralisation Efficacy of MDP Utilized on the Bonding Performance of MDP-based all-in-one Adhesives. J. Dent. 2018, 77, 59–65. 10.1016/j.jdent.2018.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujita Nakajima K.; Nikaido T.; Arita A.; Hirayama S.; Nishiyama N. Demineralization Capacity of Commercial 10-Methacryloyloxydecyl Dihydrogen Phosphate-based all-in-one Adhesive. Dent. Mater. 2018, 34, 1555–1565. 10.1016/j.dental.2018.06.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukegawa D.; Hayakawa S.; Yoshida Y.; Suzuki K.; Osaka A.; Van Meerbeek B. Chemical Interaction of Phosphoric Acid Ester with Hydroxyapatite. J. Dent. Res. 2006, 85, 941–944. 10.1177/154405910608501014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Z.; Wang X.; Zhang L.; Liang B.; Tang T.; Fu B.; Hannig M. The Contribution of Chemical Bonding to the Short- and Long-term Enamel Bond Strengths. Dent. Mater. 2013, 29, e103–e112. 10.1016/j.dental.2013.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szesz A.; Parreiras S.; Reis A.; Loguercio A. Selective Enamel Etching in Cervical Lesions for Self-Etch Adhesives: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Dent. 2016, 53, 1–11. 10.1016/j.jdent.2016.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pouyanfar H.; Tabaii E. S.; Aghazadeh S.; Nobari S. P. T. N.; Imani M. M. Microtensile Bond Strength of Composite to Enamel Using Universal Adhesive with/without Acid Etching Compared to Etch and Rinse and Self-Etch Bonding Agents. Open Access Maced. J. Med. Sci. 2018, 6, 2186–2192. 10.3889/oamjms.2018.427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Munck J.; Van Landuyt K.; Peumans M.; Poitevin A.; Lambrechts P.; Braem M.; Van Meerbeek B. A Critical Review of the Durability of Adhesion to Tooth Tissue: Methods and Results. J. Dent. Res. 2005, 84, 118–132. 10.1177/154405910508400204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cardenas A. F. M.; Siqueira F. S. F.; Bandeca M. C.; Costa S. O.; Lemos M. V. S.; Feitora V. P.; Reis A.; Loguercio A. D.; Gomes J. C. Impact of pH and Application Time of Meta-Phosphoric Acid on Resin-Enamel and Resin-Dentin Bonding. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 2018, 78, 352–361. 10.1016/j.jmbbm.2017.11.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sai K.; Shimamura Y.; Takamizawa T.; Tsujimoto A.; Imai A.; Endo H.; Barkmeier W. W.; Latta M. A.; Miyazaki M. Influence of Degradation Conditions on Dentin Bonding Durability of Three Universal Adhesives. J. Dent. 2016, 54, 56–61. 10.1016/j.jdent.2016.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gale M. S.; Darvell B. W. Thermal Cycling Procedures for Laboratory Testing of Dental Restorations. J. Dent. 1999, 27, 89–99. 10.1016/S0300-5712(98)00037-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki S.; Takamizawa T.; Imai A.; Tsujimoto A.; Sai K.; Takimoto M.; Barkmeier W. W.; Latta M. A.; Miyazaki M. Bond Durability of Universal Adhesive to Bovine Enamel Using Self-Etch Mode. Clin. Oral Invest. 2018, 22, 1113–1122. 10.1007/s00784-017-2196-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Landuyt K. L.; De Munck J.; Snauwaert J.; Coutinho E.; Poitevin A.; Yoshida Y.; Inoue S.; Peumans M.; Suzuki K.; Lambrechts P.; Van Meerbeek B. Monomer-Solvent Phase Separation in One-Step Self-Etch Adhesives. J. Dent. Res. 2005, 84, 183–188. 10.1177/154405910508400214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abdalla A. I.; Feilzer A. J. Four-Year Water Degradation of a Total-Etch and Two Self-Etching Adhesives Bonded to Dentin. J. Dent. 2008, 36, 611–617. 10.1016/j.jdent.2008.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yokota Y.; Nishiyama N. Determination of Molecular Species of Calcium Salts of MDP Produced Through Decalcification of Enamel and Dentin by MDP-based One-Step Adhesive. Dent. Mater. J. 2015, 34, 270–279. 10.4012/dmj.2014-260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshihara K.; Yoshida Y.; Hayakawa S.; Nagaoka N.; Irie M.; Ogawa T.; Van Landuyt K. L.; Osaka A.; Suzuki K.; Minagi S.; Van Meerbeek B. Nanolayering of Phosphoric Acid Ester Monomer on Enamel and Dentin. Acta Biomater. 2011, 7, 3187–3195. 10.1016/j.actbio.2011.04.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malacarne J.; Carvalho R. M.; de Goes M. F.; Svizero N.; Pashley D. H.; Tay F. R.; Yiu C. K.; Carrilho M. R. Water Sorption/Solubility of Dental Adhesive Resins. Dent. Mater. 2006, 22, 973–980. 10.1016/j.dental.2005.11.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen C.; Niu L. N.; Xie H.; Zhang Z. Y.; Zhou L. Q.; Jiao K.; Chen J. H.; Pashley D. H.; Tay F. R. Bonding of Universal Adhesives to Dentine--Old Wine in New Bottles?. J. Dent. 2015, 43, 525–536. 10.1016/j.jdent.2015.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skovron L.; Kogeo D.; Gordillo L. A.; Meier M. M.; Gomes O. M.; Reis A.; Loguercio A. D. Effects of Immersion Time and Frequency of Water Exchange on Durability of Etch-and-Rinse Adhesive. J. Biomed. Mater. Res., Part B 2010, 95B, 339–346. 10.1002/jbm.b.31718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujiwara S.; Takamizawa T.; Barkmeier W. W.; Tsujimoto A.; Imai A.; Watanabe H.; Erickson R. L.; Latta M. A.; Nakatsuka T.; Miyazaki M. Effect of Double-layer Application on Bond Quality of Adhesive Systems. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 2018, 77, 501–509. 10.1016/j.jmbbm.2017.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]