Abstract

Background:

The increased number of deaths in the community happening as a result of COVID-19 has caused primary healthcare services to change their traditional service delivery in a short timeframe. Services are quickly adapting to new challenges in the practical delivery of end-of-life care to patients in the community including through virtual consultations and in the provision of timely symptom control.

Aim:

To synthesise existing evidence related to the delivery of palliative and end-of-life care by primary healthcare professionals in epidemics and pandemics.

Design:

Rapid systematic review using modified systematic review methods, with narrative synthesis of the evidence.

Data sources:

Searches were carried out in Medline, Embase, PsychINFO, CINAHL and Web of Science on 7th March 2020.

Results:

Only five studies met the inclusion criteria, highlighting a striking lack of evidence base for the response of primary healthcare services in palliative care during epidemics and pandemics. All were observational studies. Findings were synthesised using a pandemic response framework according to ‘systems’ (community providers feeling disadvantaged in terms of receiving timely information and protocols), ‘space’ (recognised need for more care in the community), ‘staff’ (training needs and resilience) and ‘stuff’ (other aspects of managing care in pandemics including personal protective equipment, cleaning care settings and access to investigations).

Conclusions:

As the COVID-19 pandemic progresses, there is an urgent need for research to provide increased understanding of the role of primary care and community nursing services in palliative care, alongside hospices and community specialist palliative care providers.

Keywords: Pandemics, epidemics, coronavirus, influenza, human, primary health care, general practice, physicians, family, palliative care, death

What is already known?

Primary healthcare services play an important role in the provision of palliative care during pandemics, such as COVID-19.

Pandemics and epidemics are associated with an increased number of deaths and increased need for palliative care in the community.

The increased number of deaths and new challenges in end of life care through the COVID-19 pandemic, including symptom profiles, video consultations and the need for personal protective equipment, has placed clear focus on the need for palliative care in all community settings, including care homes.

What this paper adds

This review reveals a stark and concerning lack of evidence from previous pandemics related to primary healthcare services in palliative care provision within a pandemic.

Important factors in a successful primary healthcare palliative care response to pandemics include consistent and timely communication between policy makers and healthcare providers; education, training and debrief for the workforce; support for family carers; and continued delivery of equipment and access to necessary support services, such as diagnostic tests.

Implications for practice and policy

The review presents a compelling case for more research into the role and response of primary healthcare services in the delivery of palliative care during pandemics, as we progress through the next phases of the COVID-19 pandemic and for future pandemics.

A whole system response to the increased need for palliative care in the community is required, so the findings of this review and future research in this field are of relevance to hospice and specialist palliative care services, as well as policy makers.

Introduction

The provision of palliative and end-of-life care to patients, families and communities is core to the role and identity of primary healthcare clinicians. They are central to the provision of this care and in supporting, and advocating for, patients and their families.1–4 The primary healthcare workforce is diverse, including general practitioners (or family physicians), community nurses, healthcare and support workers. These professionals have the potential to deliver palliative care integrated into every encounter in the community when their working environment allows this, and with the support of specialist colleagues.5 Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, barriers to effective palliative and end-of-life care in the community from the perspective of United Kingdom general practitioners included a lack of time with patients and families, inadequate support services in the community, a need for more education and training, and inconsistent access to specialist palliative care services.6,7

The COVID-19 pandemic has been associated with an increased number of deaths in the community, including in care homes.8 There are challenging new symptom profiles9 and changes in the way consultations are conducted, with personal protective equipment required or consultations taking part via videoconference.10 This has significant implications for primary healthcare care teams providing palliative care (the relief of suffering associated with life-threatening conditions) and care of the dying (end-of-life care), alongside providers of specialist palliative care, including hospices.

Palliative care has been recognised as a key part of national and international pandemic responses.11 A rapid review of the role and response of hospices and specialist palliative care services conducted early in the COVID-19 pandemic highlighted the need for such services to respond rapidly and flexibly during pandemics, including shifting resources into the community.12 However, a whole system approach is needed, and the role and response of primary healthcare teams and services must be considered alongside that of specialist palliative care services in order to establish collaborative ways of working to meet increased need. This aim of this review was to review the evidence base related to palliative care provision by primary healthcare teams during epidemics and pandemics, in order to inform policy and practice during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Methods

Patient and public involvement

A Patient and Public Involvement consultation exploring the challenges facing palliative care service users and their families during COVID-19 concluded there was an urgent need to provide improved care in the community.13 The results of this consultation informed the review question and design. Further patient and public involvement took place as the review was conducted with The University of Sheffield Palliative Care Studies Advisory Group, a group of 15 lay advisors with personal experience of palliative care either as patients or carers. They were established through the University of Sheffield in 2009 and have regularly contributed to palliative and end-of-life care research. The group provided feedback on the key findings of the review and the recommendations, ensuring that these were relevant to the patient and family experience.

Review question

The aim of this review is to address the research question:

‘What is the role and response of primary healthcare services in the delivery of palliative care in epidemics and pandemics?’

Design

This rapid review was conducted using modified systematic review methods, refined from the Centre for Reviews and Dissemination guidance for systematic reviews in healthcare14 and informed by rapid review methods outlined by the Palliative Care Evidence Review Service,15 with a refined review question, the search carried out within a limited set of databases, and transparency in the reporting. The structure and content of the review is informed by the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) Guidelines.16 A protocol has been registered and published on the PROSPERO database (ref no: CRD42020186010).

Inclusion/exclusion criteria

Table 1 provides details of the inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Table 1.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria.

| PICOS dimension | Inclusion | Exclusion |

|---|---|---|

| Population | Patients receiving palliative and end-of-life care in the community, home or care homes | Patients receiving palliative and end-of-life care in hospice, hospital or any other inpatient setting such as temporary hospital units |

| Intervention | Palliative care/end-of-life care delivered by primary healthcare services (including general practitioners/family physicians/community and district nursing services/paid community health workers and assistants | Hospice and specialist palliative care services |

| Community volunteer services | ||

| Other medical specialties | ||

| Public health palliative care approaches | ||

| Context | Epidemics or pandemics including those caused by respiratory viruses, Ebola and TB. | HIV and other sexually transmitted infections |

| Studies not concerning pandemics/epidemics | ||

| Comparator | Usual care | |

| Outcomes | Any formal measure of evaluation concerning the acceptability or effectiveness of palliative care delivered by primary care and community nursing | |

| Study design | Any evaluative study design | Review and practice articles, editorials, descriptive or theoretical papers that did not present original research findings |

| Publication | No date or language limits Unpublished grey literature |

Voluntary sector reports |

Search strategy

Searches were conducted in Medline, Embase, PsychINFO, CINAHL and Web of Science, by a specialist librarian at the University of Sheffield on 7th March 2020. The search strategy included the following search terms and is detailed in Appendix 1.

Terms for palliative care, end-of-life care, primary care and family practice, community nursing, district nursing

Terms for pandemics and epidemics including specific named pandemics

Further relevant articles that were known to the authors were included. Others were identified through forward and backward citation searching of articles and the reference lists of guidelines from the COVID-19 pandemic.

Study selection

Title and abstracts were uploaded into EndNote and duplicates were removed. Two reviewers (SM and VM) screened article titles and abstracts for relevance independently. Those considered potentially eligible for inclusion were retrieved as full text articles, and three members of the review team (SM, VM and VL) assessed them against the inclusion and exclusion criteria, and discussed whether they would be included.

Data extraction

Data was extracted into a bespoke data extraction form in Microsoft Excel that included the study title, date, location, study design and key findings by two researchers (SM and VL) and independently checked for accuracy and detail by a third (VM).

Quality assessment

Quality assessment of the evidence was attempted using a method and tools proposed by the Palliative Care Evidence Review Service, outlined as suitable for rapid reviews in palliative care.13,16 This quality assessment was conducted by one reviewer (SM) and checked by two others (VM and VL) and disagreements were discussed.

Data synthesis

The included studies were compared in the data extraction table. There were no comparable statistics and therefore a narrative synthesis was undertaken, identifying cross-cutting themes from each study. The narrative synthesis was constructed using Downar and Seccareccia’s model that suggests a palliative pandemic plan should include focus on ‘systems’, ‘space’, ‘staff’ and ‘stuff’.17 This was chosen to mirror Etkind et al.’s rapid review of hospice and specialist palliative care services, on the basis that primary healthcare services work alongside hospice and specialist services in the practical delivery of palliative care to patients.11 The narrative was reviewed at intervals for relevance to clinical practice and family experience by the Oxford Centre for Evidence Based Medicine COVID-19 rapid reviews in palliative care group, and patient and public involvement representatives.

Findings

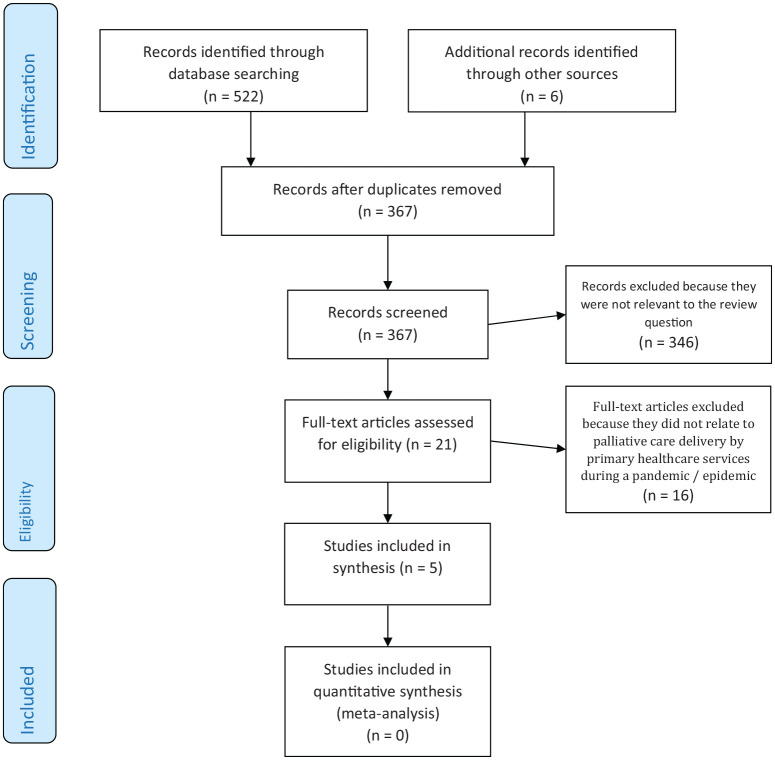

Study selection: A total of 522 articles were identified during the searches (search date 7th May 2020), with six additional papers identified in articles known to the research team and through screening the reference lists of relevant articles and reports. Following removal of duplicates, 367 articles remained for title and abstract screening. Twenty-one articles underwent full text review. After applying the inclusion and exclusion criteria, only five articles were identified,18–22 one of which was only available as a conference abstract.22 Sixteen were excluded because they did not relate to palliative care delivery by primary healthcare services during a pandemic/epidemic. This process is shown in Figure 1. The search was repeated on 2nd July 2020, but no new articles were identified that met the inclusion criteria for this review.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram.

Study location: Of the five articles that met the inclusion criteria, one was from Canada,18 one from the UK,22 one from the USA20 and the others written by collaboratively between teams in the UK and South Africa19 and the USA and South Africa.21

Study design: All of the identified studies were observational, there were no randomized-controlled trials or systematic reviews. One was a qualitative interview study of patients with uncured TB,19 one was a survey of general practitioners and family physicians,18 one was an evaluation of a community acute care centre,20 one was a qualitative interview study of community support workers and evaluation of an educational programme,21 and the other reported epidemiological data.22

Study quality: Together the studies represented a heterogeneous and very small body of evidence. Quality appraisal was attempted on the four full-text articles, three of which were research studies.18,19,21 All had ethics approvals in place and acknowledged the limitations of the study design and findings. The fourth full-text article was a description of care centres and learning from their implementation, rather than a research study.20 Quality appraisal was not conducted on the abstract as there was insufficient information available to do so.22 So few articles were identified that none were excluded on the basis of the quality appraisal.

Study characteristics are summarised in Table 2.

Table 2.

Summary of study characteristics.

| Author/title | Country | Year of publication | Aim/Target population | Study design | Key findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jaakkimainen RL et al. How infectious disease outbreaks affect community-based primary care physicians18 | Canada | 2014 | To understand the perceptions of general practitioners and family physicians in the provision of primary care during the H1N1 outbreak, and compare to similar survey in 2003. Target population: General practitioners and family physicians |

Mailed survey of general practitioners and family physicians. Analysis using descriptive statistics. | The study provided findings related to the broad issues for primary healthcare physicians in infectious disease outbreaks, including (but not specifically) concerns re. nursing home care, housecalls and palliative care (“out-of-office” care). Respondents indicated they would make changes to their office practice, provide extra clinical care, concern about the overall provision of healthcare services, and a desire for timely and accurate information. Low % of respondents felt confident that all levels of government would work together. Workforce shortage felt to have a serious impact on the local healthcare system’s ability to prepare. Practice changed between two outbreaks, with later outbreak associated with more personal protective equipment use, more investigations (bloods and chest x-rays), seeing patients faster and measurements e.g. temperature as part of assessment, more travel advice, washing hands, and cleaning surfaces between patients. |

| Senthilingam M et al. Lifestyle, attitudes and needs of uncured XDR-TB patients living in the communities of South Africa: a qualitative study19 | UK/South Africa | 2015 | To understand the experiences of patients living in the community with uncured TB. Target population: Community-based patients |

Qualitative interview study with 12 participants (including patients and family carers) | Need for more care in the community, particularly psychosocial and care for carers. Patients felt isolated and wanted purpose. Community based palliative care proposed as a way of improving quality of life, reducing isolation and improve economic opportunities. |

| Cinti et al. Pandemic Influenza and Acute Care Centres: Taking care of sick patients in a non-hospital setting20 | USA | 2008 | To understand the organisation of care in the community in acute care centres during the H5N1 avian influenza outbreak. | Evaluation of acute care centres (A regional medical co-ordination centre and neighbourhood emergency help centres) | Mostly focused on hospital type triage and active management. Learning from the evaluation highlighted the need to include community services (home care nurses) as they had an important role in transitioning palliative patients back home. Acknowledged lack of attention to palliative care in modelling for epidemic. Decision to develop ‘mass palliative care protocols’. |

| Campbell et al. Community health workers palliative care learning needs and training: results from a partnership between a US university and a rural community organisation in Mpumalanga Province, South Africa21 | USA/South Africa | 2016 | To understand the training needs and priorities of community health workers in palliative care. Target population: Paid community health workers |

Focus groups with 29 community health workers | Learning needs identified and prioritised—HIV/palliative care / debriefing. Debriefing was the most surprising but demonstrates impact on staff of caring for very sick people (in the context of HIV and TB epidemics)—recognised importance of self care, impact of multiple losses, moral distress over ethical issues and work within limited resources. Identified effective strategies for education inc role plays and narratives, train the trainer, resources and ongoing educational programme. Not specific to one pandemic. Need for evaluation of pall care delivered by community health workers recognised. |

| Fleming D. The impact of three influenza epidemics on primary care in England and Wales (abstract only)22 | UK | 1996 | To understand the impact of influenza pandemics on primary care. Target population: Patients who consulted general practice during influenza pandemics |

Epidemiological study | During the 3 epidemic periods, increased numbers of persons consulted their general practitioners with other respiratory diseases, including pneumonia, acute bronchitis and otitis media. The patterns of increase were not consistent between the epidemics, partly because of the differing impact on the various age groups and partly because of the effect of other respiratory viral illnesses prevalent at the same time. No increase occurred in the numbers of persons reported with new episodes of cerebrovascular accident or of acute myocardial infarction. A similar method was used to estimate excess deaths, which amounted to 25,000 in 1989, 13,000 in 1993, and 500 in 1995. In the periods immediately following the influenza epidemics, the observed pattern of deaths conformed to the expected, demonstrating that persons dying during the epidemics were not just dying a few weeks prematurely. |

Key themes

The articles together provided very limited insights into the role and response of primary healthcare services in palliative care delivery during pandemics. We therefore used the pandemic response framework15 to categorise what little data that was available into ‘systems’ (data that provided insights into wider healthcare systems including policy), ‘space’ (insights into primary healthcare delivery of palliative care in the community), ‘staff’ (workforce concerns) and ‘stuff’ (all other relevant concerns; see Table 3).17

Table 3.

Synthesis of evidence and recommendations for the response of primary care to palliative care delivery during a pandemic.

| Element of the response model | Findings of the review |

|---|---|

| Systems |

Policies

• Need for consistent and timely communications re. protocols and public health measures to primary healthcare services during pandemics18 • Recognised lack of attention to palliative care in modelling for epidemics20 • Low % of general practitioners feel confident in levels of government (national/local) working effectively together during pandemics18 |

| Space |

Provision of care at home

• Previous pandemics have shown excess numbers of deaths in the community22 • Recognised need for more palliative care in the community19 including when patients are transitioned home for end-of-life care20 • Recognition that family carers may have to take on additional responsibilities and a clearly outlined need for psychosocial support19 • Need for emotional and financial support for family carers including debriefing21 and relief of responsibility19 |

| Staff |

General practice workforce

• Shortage of general practitioners impacts on the ability to prepare for infectious disease pandemics18 • General practitioners were personally prepared to provide extra capacity18 Training and skills development • Palliative care was identified as a priority for training during pandemics for community health workers21 Staff resilience • Importance of ‘debriefing’ defined as a time to talk about the impact of caring for sick people on the emotional well-being of healthcare workers21 • Recognised importance of self-care, impact of multiple losses, moral distress over ethical issues and work within limited resources21 |

| Stuff | The impact of other aspects of care delivery during pandemics were highlighted but not specifically in relation to palliative care. These included personal protective equipment, distancing, cleaning consulting areas, and adequate access to equipment and diagnostic tests including blood tests and x-rays.18 |

Systems

Excess deaths in the community during a pandemic have an impact on primary healthcare services,22 however a lack of attention to palliative care was noted in pandemic planning and service modelling in general practice and community services, despite the need for ‘mass palliative care protocols’ being raised during past pandemic influenza outbreaks.20 In one study, a low number of general practitioner respondents felt confident that all levels of government would work together to provide the information that they needed to prepare their services for a pandemic.18 There were also concerns that primary healthcare services were disadvantaged with respect to consistent and timely communications about policy and processes, such as screening protocols, treatment protocols, public health measure summaries and information from local hospitals, although this was not specifically in relation to palliative care.18

Space

The studies provided limited insights into the importance of the community as a care setting, with a need for more palliative care in community settings during pandemics. Community based palliative care was proposed as a way of improving quality of life and reducing isolation.19 The important role of community nurses in transitioning patients discharged from acute hospitals and care centres to receive palliative and end-of-life care in the community was specifically highlighted.20

Only one study included patient data, relevant to the provision of palliative care in the community during pandemics. Patients stated that reasons for choosing to receive care at home included the trauma of seeing others die of the same disease in hospital, and the associated removal of hope.19 The need for psychosocial care for patients who were at particular risk of feeling isolated due to their infection risk, and support for family carers in the community, were pressing concerns.19 The importance of debrief for family members who were ‘chosen by healthcare services to be responsible’ for aspects of patient care was described, as well as the need for services to be able to provide occasional relief of some of that responsibility.19

Staff

The studies together described a range of primary healthcare professionals involved in palliative and end-of-life care during pandemics, including general practitioners, community nurses and community health workers. Workforce concerns included inadequate numbers of community nurses21 and general practitioners,18 with solutions including the employment of community health workers,21 and individual general practitioners expressing a willingness to work longer hours and personally provide extra capacity during pandemics.18

Palliative care was identified as a specific training need for community health workers during pandemics, with effective strategies for education including role plays and narratives, training the trainer, online resources and an ongoing educational programme.21 The importance of ‘debriefing’, defined as a time to talk about the impact of caring for sick people, on the emotional wellbeing of healthcare workers, was described as ‘surprising’ finding, but was valuable to staff who were dealing with the impact of multiple losses, moral distress over ethical issues and work within limited resources.21

Stuff

Palliative care was recognised as one aspect of care provided in primary healthcare of importance during pandemics, alongside many others. Other aspects of care provision during a pandemic that caused concern for the organisation of primary healthcare services included the need for personal protective equipment, distancing, regular of cleaning consulting areas, access to equipment and timely diagnostic tests including blood tests and x-rays.18

Discussion

Main findings

This rapid review reveals a stark lack of evidence around the role of primary healthcare services in palliative care provision during pandemics. The five papers that were identified highlighted the need for more palliative care in the community during pandemics, and that primary healthcare services have a role in the provision of such care within their wider work and pandemic response. The limited evidence that was available could be aligned with a pandemic response framework for palliative care,17 however there is currently insufficient evidence to support the development of a framework to either improve understanding of the role, or enabling the response of, primary healthcare services in the delivery of palliative care during pandemics. No evidence was identified that has been conducted in this area during the COVID-19 pandemic. The review provides a compelling case for research to capture the learning, experiences, effective innovations and service developments that are happening now in this important aspect of care in the community during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Strengths and limitations

A strength of the study is its specific focus on primary healthcare services in the provision of palliative care during pandemics. However, the body of evidence included in this review was very small, and heterogeneous in terms of study design. All of the studies were observational, and the generalisability of their findings is limited. Palliative and end-of-life care in primary care was considered amongst many issues being studied in the research, rather than as a focus for research in it’s own right. Furthermore, the very specific focus of the review has excluded any previous research into the delivery of palliative care in primary care more broadly that also has relevance to the delivery of such care during the current COVID-19 pandemic and future pandemics.

What this study adds

Past pandemic plans and frameworks for primary care place focus on surge in demand for primary care services in their entirety, sustaining urgent and essential services, public health responsibilities including infection control and immunisation, ensuring clinical facilities and equipment are adequate, and maintaining business continuity.23 There appears to be some disconnect between this and the need for more palliative care in the community during pandemics, including the current COVID-19 pandemic.11,24–26 This review highlights the need for more research into palliative and end-of-life care to inform future plans and frameworks for the response of primary healthcare services to a pandemic.

Observations in primary healthcare practice in the UK are that the provision of palliative and end-of-life care has been a significant role for these teams during the COVID-19 pandemic, including in care homes. Some aspects of palliative care, such as advance care planning, have received attention in national general practice policy documents with recommendations made during COVID-19 in the National Health Service in England.27 However there are many more new challenges associated with COVID-19 and the delivery of palliative care in the community, and there is an imperative to learn from these now, particularly as COVID-19 becomes a longer term issue.28 These challenges include the greater risk of virus transmission and lethality compared to other viruses, the need for personal protective equipment in consultations, concerns about limited drug supplies and the equipment necessary for symptom control, and patients being isolated from their families and carers at the end of their lives. Out-of-hours palliative and end-of-life care provision is also an important concern. This review suggests factors in a successful primary palliative care response to a pandemic include consistent and timely communication between policy makers and primary healthcare providers; education, training and debrief for the workforce; support for family carers; continued delivery of equipment and access to necessary support services, such as diagnostic tests. However, much more evidence is needed to inform such a response.

There are other important considerations in the role and response of primary healthcare services to palliative care in COVID-19 and future pandemics. The needs of family carers, who may be apart from their dying relatives or who may have to take on increased responsibility for hands-on care of a relative during pandemics, must be considered. They may have a need for psychosocial support, debrief and relief of the responsibility, as well as training, if they are to take on aspects of care including the administration of end-of-life drugs.29 More research into the impact of COVID-19 deaths on subsequent bereavement is also necessary.30 Recognition of the role and potential of primary healthcare teams, within the communities they serve is required, alongside consideration of the role and response of hospice and specialist palliative care services in pandemics, is required in order to deliver care to patients and families as effectively as possible. Local and regional variations in practice and the development of collaborative relationships between generalist and specialist providers of palliative care must be better understood to inform national policy and recommendations for service delivery during the next phases of COVID-19 and future pandemics.

Taking the findings of the review, and working in partnership with patient and public involvement representatives, four very broad recommendations have been developed, summarised in Table 4. Group members supported the recommendations for shared learning, the need for emphasis on staff and family carer resilience and measures to foster this, and increased support for family carers. They raised further concerns around access to personal protective equipment for healthcare staff, support for care homes, and the extent to which community involvement in palliative care could and should continue post-COVID 19, all of which are important considerations for future research.

Table 4.

Recommendations from the review.

| The role and response of general practice and community nursing services in the delivery of palliative care during pandemics: Recommendations from the review | |

|---|---|

| 1 | There is a need for more palliative care in the community during pandemics. Primary healthcare services have an important role in the delivery of such care in collaborative service models with specialist palliative care providers. |

| 2 | Pandemic plans and frameworks for general practice and community services should include their role in palliative and end-of-life care. |

| 3 | Training and education in palliative care is required to address learning needs for community healthcare staff and in order to support family carers during pandemics. |

| 4 | There is an urgent need for more research into the role and response of primary healthcare services in palliative care delivery during COVID-19 and future pandemics. |

Conclusion

Primary healthcare services have an important role to play in the provision of palliative care to all who need it, alongside providers of hospice and specialist palliative care services. During a pandemic, there is a risk of increased numbers of deaths and primary healthcare services need to be able to respond effectively, alongside specialist palliative care services including hospices. This is an important consideration for clinicians, primary healthcare service managers and for policy makers. There is an urgent need for research to inform recommendations for how the response to increased need for palliative care in the community in primary healthcare, through both the COVID-19 pandemic and future pandemics, and for pandemic planning to include this aspect of patient care.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank University of Oxford Centre for Evidence Based Medicine rapid reviews in palliative care team, Prof Irene Higginson (Kings College London), and the Sheffield Palliative Care Studies Advisory Group for their input and advice to this study. Thank you also to Anthea Tucker, specialist librarian at the University of Sheffield, for conducting the searches.

Appendix 1: Search details

All searches conducted on 7th May 2020

Medline = 128

Embase = 209

CINAHL = 62

PsycINFO = 27

Web of Science = 96

Total = 522

After duplicates removed = 361

Database: Ovid MEDLINE(R) and Epub Ahead of Print, In-Process & Other Non-Indexed Citations and Daily <1946 to May 06, 2020>

Search Strategy:

————————————————————————————————————————

1 palliative care/ or palliative medicine/ or palliat*.mp. or hospices/ or terminally ill/ or terminal care/ or terminal*.mp. or hospice*.mp. or end of life.mp. or EOL.mp. or dying.mp. (618292)

2 exp pandemics/ or pandemic*.mp. or epidemic*.mp. or epidemics/ or exp disease outbreaks/ or disease outbreak*.mp. or SARS.mp. or SARS-CoV-2.mp. or SARS virus/ or Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome/ or coronavirus/ or coronavirus.mp. or covid-19.mp. or exp coronavirus infections/ or ebolavirus/ or influenza, human/ or influenza.mp. or hemorrhagic fever, ebola/ or mers.mp. or flu.mp. or Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus/ or Tuberculosis/ or Pulmonary tuberculosis/ or Tuberculosis, multi-drug resistant/ or Extensively drug resistant tuberculosis/ or TB.mp. (488494)

3 1 and 2 (5656)

4 exp Community Health Nursing/ or Primary Care Nursing/ or primary care.mp. or exp Primary Health Care/ or primary medical care.mp. or primary healthcare.mp. or family practice.mp. or general practi*.mp. or GP.mp. or GPs.mp. or family physician*.mp. or family doctor*.mp. or family practi*.mp. or physicians, family/ or physicians, primary care/ or district nurs*.mp. or community nurs*.mp. or community health services/ or (communit* adj3 health).mp. (486878)

5 3 and 4 (127)

***************************

Database: Embase <1974 to 2020 May 06>

Search Strategy:

————————————————————————————————————————

1 palliative care/ or palliative medicine/ or palliate*.mp. or hospices/ or terminally ill/ or terminal care/ or terminal$.tw. or hospice*.mp. or end of life.mp. or EOL.mp. or dying.mp. (684647)

2 exp pandemics/ or pandemic*.mp. or epidemic*.mp. or epidemics/ or exp disease outbreaks/ or disease outbreaks.mp. or SARS.mp. or SARS virus/ or Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome/ or coronavirus/ or coronavirus.mp. or covid-19.mp. or SARS-CoV-2.mp. or exp coronavirus infections/ or ebolavirus/ or influenza, human/ or influenza.mp. or hemorrhagic fever, ebola/ or mers.mp. or flu.mp. or Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus/ or Tuberculosis/ or Pulmonary tuberculosis/ or Tuberculosis, multi-drug resistant/ or Extensively drug resistant tuberculosis/ or TB.mp. (534940)

3 1 and 2 (7330)

4 exp Community Health Nursing/ or Primary Care Nursing/ or primary care.mp. or exp Primary Health Care/ or primary medical care.mp. or primary healthcare.mp. or family practice.mp. or general practi*.mp. or GP.mp. or GPs.mp. or family physician*.mp. or family doctor*.mp. or family practi*.mp. or physicians, family/ or physicians, primary care/ or district nurs*.mp. or community nurs*.mp. or community health services/ or (communit* adj3 health).tw. (553377)

5 3 and 4 (209)

***************************

Database: APA PsycInfo <1806 to May Week 1 2020>

Search Strategy:

————————————————————————————————————————

1 palliative care/ or palliat*.mp. or hospice/ or terminally ill patient/ or terminal care.mp. or hospice*.mp. or end of life.mp. or EOL.mp. or dying.mp. (54294)

2 exp pandemics/ or pandemic*.mp. or epidemic*.mp. or exp epidemics/ or disease outbreaks.mp. or SARS.mp. or Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome.mp. or coronavirus.mp. or COVID-19.mp. or SARS-CoV-2.mp. or influenza/ or swine influenza.mp. or ebola.mp. or ebolavirus.mp. or influenza.mp. or mers.mp. or flu.mp. or Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus.mp. or Tuberculosis/ or Pulmonary tuberculosis/ or multi-drug resistant tuberculosis.mp. or extensively drug resistant tuberculosis.mp. or TB.mp. (19790)

3 1 and 2 (561)

4 Primary Care Nursing/ or primary care.mp. or exp Primary Health Care/ or primary medical care.mp. or primary healthcare.mp. or family practice.mp. or general practi*.mp. or GP.mp. or GPs.mp. or family physician*.mp. or family doctor*.mp. or family practi*.mp. or physicians, family/ or physicians, primary care/ or district nurs*.mp. or community nurs*.mp. or community health services/ or (communit* adj3 health).mp. (84321)

5 3 and 4 (27)

***************************

CINAHL

1 S4 S1 AND S2 AND S3 (62)

2 S3 “primary care” or “primary healthcare” or “primary health care” or “primary medical care” or “general practi*” or GP or GPs or “family physician*” or “family doctor*” or “family practi*” or “district nurs*” or “community nurs*” or “community health” or “Physicians, Family” (223,942)

3 S2 pandemic* or epidemic* or “disease outbreak*” or SARS or SARS-CoV-2 or “Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome” or coronavirus or covid-19 or ebola* or influenza or mers or flu or “Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus” or tuberculosis or TB Expanders - Apply equivalent subjects (111,490)

4 S1 palliat* or terminal* or hospice* or “end of life” or EOL or dying Expanders - Apply equivalent subjects (117,677)

————————————————————————————————————————

Web of Science

Databases = WOS, BCI, BIOSIS, CCC, DRCI, DIIDW, KJD, MEDLINE, RSCI, SCIELO, ZOOREC Timespan = All years

Search language = Auto

# 4 96 #3 AND #2 AND #1

# 3 1,065,454 TOPIC: (“primary care” or “primary health care” or “primary medical care” or “primary healthcare” or “family practi*” or “general practi*” or “GP” or “GPs” or “family physician*” or “family doctor*” or “family practi*” or “district nurs*” or “community nurs*” or “community health”)

# 2 928,005 TOPIC: (pandemic* OR epidemic* OR “disease outbreak*” OR “Severe acute respiratory syndrome” OR “SARS” OR “SARS-CoV-2” OR coronavirus OR covid-19 OR influenza OR “flu” OR “MERS” OR “middle east respiratory syndrome” OR ebola* OR tuberculosis)

# 1 244,532 TOPIC: (“palliat*” OR “hospice*” OR “terminal care” OR “terminally ill” OR “eol” OR “end of life” OR “dying”)

Footnotes

Authorship statement: SM designed the study. SM, VM and VL retrieved and analysed the data, and drafted the article. CG liaised with the PPI advisory team. CG and NJ revised the article critically for clarity and intellectual content. All authors have approved this version for submission.

Declaration of conflicting interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Research ethics: This is a rapid review of published literature. It did not require any ethical review and did not raise any ethical concerns in its conduct.

ORCID iDs: Sarah Mitchell  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1477-7860

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1477-7860

Clare Gardiner  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1785-7054

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1785-7054

References

- 1. Luker KA, Austin L, Caress A, et al. The importance of ‘knowing the patient’: community nurses’ constructions of quality in providing palliative care. J Adv Nurs 2000; 31(4): 775–782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Walshe C, Luker KA. District nurses’ role in palliative care provision: a realist review. Int J Nurs Studies 2010; 47(9): 1167–1183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ramanayake RPJC, Dilanka GVA, Premasiri LWSS. Palliative care; role of family physicians. J Family Med Prim Care 2016; 5(2): 234–237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Park S, Abrams R. Alma-Ata 40th birthday celebrations and the Astana Declaration on Primary Health Care 2018. Br J Gen Pract 2019; 69(682): 220–221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Brazil K, Sussman J, Bainbridge D, et al. Who is responsible? The role of family physicians in the provision of supportive cancer care. J Oncol Pract 2010; 6(1): 19–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Mitchell S, Loew J, Millington-Sanders C, et al. Providing end-of-life care in general practice: findings of a national GP questionnaire survey. Br J Gen Pract 2016; 66(650): e647–e653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. GPs call for more time to meet needs of terminally ill patients [press release]. https://www.mariecurie.org.uk/media/press-releases/gps-call-for-more-time-with-terminally-ill/147700 (2016, accessed 8 July 2020).

- 8. Office for National Statistics (ONS). Coronavirus (COVID-19): latest data and analysis on coronavirus (COVID-19) in the UK and its effect on the economy and society, https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/healthandsocialcare/conditionsanddiseases (accessed 8 July 2020).

- 9. Managing COVID-19 symptoms (including at the end of life) in the community: summary of NICE guidelines. Br Med J 2020; 369: m1461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Thornton J. Covid-19: how coronavirus will change the face of general practice forever. Br Med J 2020; 368: m1279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. The Lancet Commission on Palliative Care and Pain Relief. Palliative care and the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet 2020; 396: 1168. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Etkind SN, Bone AE, Lovell N, et al. The role and response of palliative care and hospice services in epidemics and pandemics: a rapid review to inform practice during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Pain Sympt Manage. Epub ahead of print 8 April 2020. DOI: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2020.03.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Johnson B, Clark R, Pocock L, et al. Patient and family concerns and priorities for palliative care during the COVID-19 pandemic: a rapid on-line consultation to hear their missing voices. Palliat Med 2020. (under review). [Google Scholar]

- 14. Centre for Reviews and Dissemination. Systematic Reviews: CRD’s guidance for undertaking reviews in health care. York: University of York; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Mann M, Woodward A, Nelson A, et al. Palliative Care Evidence Review Service (PaCERS): a knowledge transfer partnership, 10.1186/s12961-019-0504-4 (2019, accessed 8 July 2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 16. Shamseer L, Moher D, Clarke M, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015: elaboration and explanation. Br Med J 2015; 349: g7647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Downar J, Seccareccia D. Palliating a pandemic: “all patients must be cared for”. J Pain Symptom Manage 2010; 39(2): 291–295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Jaakkimainen RL, Bondy SJ, Parkovnick M, et al. How infectious disease outbreaks affect community-based primary care physicians: comparing the SARS and H1N1 epidemics. Can Fam Physician 2014; 60(10): 917–925. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Senthilingam M, Pietersen E, McNerney R, et al. Lifestyle, attitudes and needs of uncured XDR-TB patients living in the communities of South Africa: a qualitative study. Trop Med Int Health 2015; 20(9): 1155–1161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Cinti SK, Wilkerson W, Holmes JG, et al. Pandemic influenza and acute care centers: taking care of sick patients in a nonhospital setting. Biosecur Bioterror 2008; 6(4): 335–348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Campbell C, Baernholdt M. Community Health Workers’ Palliative Care Learning Needs and Training: Results from a Partnership between a US University and a Rural Community Organization in Mpumalanga Province, South Africa. J Health Care Poor Underserved 2016; 27(2): 440–449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Fleming DM. The impact of three influenza epidemics on primary care in England and Wales. Pharmacoeconomics 1996; 9(Suppl. 3): 38–45; discussion 50–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Patel MS, Phillips CB, Pearce C, et al. General practice and pandemic influenza: a framework for planning and comparison of plans in five countries. PLoS One 2008; 3(5): e2269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. MacIntyre CR, Heslop DJ. Public health, health systems and palliation planning for COVID-19 on an exponential timeline. Med J Aust 2020; 212(10): 440.e1–442.e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Radbruch L, Knaul FM, de Lima L, et al. The key role of palliative care in response to the COVID-19 tsunami of suffering. Lancet 2020; 395(10235): 1467–1469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Perry LP. To all doctors: what you can do to help as a bunch of older people are about to get sick and die. J Am Geri Soc 2020; 68(5): 944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. NHS England. Guidance and standard operating procedures General practice in the context of coronavirus (COVID-19) Version 3, 28th May 2020, https://www.england.nhs.uk/coronavirus/publication/managing-coronavirus-covid-19-in-general-practice-sop/ (accessed 26 July 2020).

- 28. Rauh AL, Linder JA. Covid-19 care before, during, and beyond the hospital. Br Med J 2020; 369: m2035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Bowers B, Pollock K, Barclay S. Administration of end-of-life drugs by family caregivers during covid-19 pandemic. Br Med J 2020; 369: m1615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Wallace CL, Wladkowski SP, Gibson A, et al. Grief during the COVID-19 Pandemic: considerations for palliative care providers. J Pain Sympt Manage 2020: e70–e76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]