Abstract

Somatic mutations driving aldosterone production have been identified in approximately 90% of aldosterone-producing adenomas (APAs) using an aldosterone synthase (CYP11B2) immunohistochemistry (IHC)-guided DNA sequencing approach. In the present study, using CYP11B2-guided whole-exome sequencing (WES) and targeted amplicon sequencing, we detected 2 somatic variants in CLCN2 in 2 APAs that were negative for currently known aldosterone-driver mutations. The CLCN2 gene encodes the voltage-gated chloride channel ClC-2. CLCN2 germline variants have previously been shown to cause familial hyperaldosteronism type II. Somatic mutations in CLCN2 were identified in 2 of 115 APAs, resulting in a prevalence of 1.74%. One of the CLCN2 somatic mutations (c.G71A,p.G24D) was identical to a previously described germline variant causing early-onset PA, but was present only as a somatic mutation. The second CLCN2 mutation, which affects the same region of the gene, has not been reported previously (c.64-2_74del). These findings prove that WES of CYP11B2-guided mutation-negative APAs can help determine rarer genetic causes of sporadic PA.

Keywords: aldosterone, primary aldosteronism, aldosterone-producing adenoma, CYP11B2, mutation, chloride channel

Primary aldosteronism (PA) is defined as inappropriately elevated aldosterone production via renin-independent mechanisms [1]. Once thought to be rare, PA is now known to be the most common cause of endocrine hypertension [2-5]. The 2 primary causes of autonomous production of aldosterone in PA are unilateral aldosterone-producing adenoma (APA, 40% of PA), which can be surgically cured, and bilateral hyperaldosteronism (BHA, 60% of PA), which is currently treated with life-long mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist therapy [6, 7]. The emergence of next-generation sequencing (NGS) has dramatically changed our understanding of the genetic landscape and molecular causes of PA. NGS of DNA from surgically removed sporadic APA samples has identified somatic aldosterone-driver mutations in genes including KCNJ5 [8], ATP1A1 [9, 10], ATP2B3 [10], and CACNA1D [9, 11]. The affected genes encode cell surface pumps/channels that lead to adrenal cell depolarization and elevated intracellular calcium (Ca2+) levels. This leads to increased aldosterone synthase (CYP11B2) expression, which in turn, results in autonomous aldosterone production. The CYP11B2 immunohistochemistry (IHC)-guided targeted amplicon sequencing method using formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tissues, which was recently developed by our group, has significantly improved the detection of somatic variants in APAs [12, 13]. Contrary to previous genetic studies that have used gross dissection of APAs, the CYP11B2-guided results have demonstrated that nearly 90% of the APAs have a known aldosterone-driver mutation [12, 13].

Previous studies have identified germline variants in CLCN2, encoding ClC-2, an inwardly rectifying chloride channel, predominately as a cause of familial hyperaldosteronism type II (FH type II). In the present study, whole-exome sequencing (WES) was performed on one APA that was found to be devoid of known aldosterone-driver mutations by our previous somatic mutation analyses [12, 13]. WES identified a somatic mutation in CLCN2 that was identical to that previously found to cause germline early-onset PA and a sporadic APA. Another novel variant in CLCN2 was later identified in another APA by targeted amplicon sequencing.

1. Materials and Methods

A. Patients

Patients diagnosed with PA (white, n = 60 male and 40 female; black, n = 8 male, 7 female), who underwent unilateral adrenalectomy at the University of Michigan, were studied. The diagnosis of PA was established as per the Endocrine Society’s clinical practice guideline [1] or the institutional consensus at that time. The availability of archival FFPE blocks of resected tumors determined the inclusion of the patients in the study. This study was approved by the institutional review board of the University of Michigan. The approval allows for the NGS analysis of somatic variants on archival tissue. Therefore, we will share limited NGS data on request.

B. Immunohistochemistry

APA FFPE sections were deparaffinized and epitope retrieval was performed by heating samples for 15 minutes in a pH 9 buffer (Vector Laboratories Inc). CYP11B2 and 17α-hydroxylase/17,20 lyase (CYP17A1) IHC on the APAs was performed as previously described [14]. After peroxidase blocking, APA FFPE sections were incubated overnight at 4oC with antihuman mouse monoclonal antibodies against CYP11B2 (clone 41-17B; diluted 1:100; Millipore Sigma; catalog No. MABS1251) [15] and visinin-like 1 (VSNL1) (diluted 1:1000; Millipore Sigma; catalog No. MABN762) [16], a rat monoclonal antibody against human 11β-hydroxylase (CYP11B1) (diluted 1:100; from Dr Gomez-Sanchez) [17]; and at room temperature for 1 hour with an antihuman rabbit polyclonal antibody against CYP17A1 (diluted 1:2000; LifeSpan Biosciences, catalog No. LS-B14227) [18]. The Polink-2 HRP Plus Mouse DAB System (GBI Labs) was used for detection. Slides were counterstained with Harris hematoxylin for 10 to 20 seconds followed by dehydration and cover-slipping.

C. DNA and RNA Isolation

Serial sections of 5 μm were prepared from the APA FFPE blocks. For each sample, slide numbers 1, 2, and 3 were used for hematoxylin and eosin staining, CYP11B2 IHC, and CYP17A1 IHC, respectively, as described previously [12, 13]. Unstained FFPE slides were dissected based on the CYP11B2 IHC results for CYP11B2-positive tumor regions and adjacent normal adrenal tissues separately using a sterile scalpel under an Olympus SZ-40 microscope. Genomic DNA (gDNA) and RNA were isolated using the AllPrep DNA/RNA FFPE kit (Qiagen) as described previously [12, 13]. gDNA was used for mutation analysis by Ion Torrent amplicon sequencing or WES, and RNA was used for gene expression by quantitative real-time reverse transcriptase (RT)–polymerase chain reaction (qPCR).

D. Quantitative Real-Time Reverse Transcriptase–Polymerase Chain Reaction

RT and qPCR were performed as described in our previous studies [12, 13]. A total of 100 ng RNA was reverse transcribed using the high-capacity complementary DNA (cDNA) archive kit (Life Technologies). For qPCR, 5 ng cDNA was mixed with TaqMan Fast Universal Master Mix (Life Technologies) following the manufacturer’s recommendations. qPCR was performed using the StepOne Plus Fast Real-Time PCR system (Applied Biosystems). The primer-probe sets for CYP11B2 were designed in house and purchased from Integrated DNA Technologies [19, 20]. The primer-probe sets for β-actin (ACTB), VSNL1, and CLCN2 were purchased from Life Technologies and those for CYP11B2, CYP11B1, and CYP17A1 were designed in house [20]. Quantitative normalization of cDNA in each tissue-derived sample was performed using the expression of ACTB as an internal control. Relative quantification was determined using the comparative threshold cycle method.

E. Whole-Exome Sequencing

WES was performed on gDNA from one of the APAs that was found to be CYP11B2-positive but mutation negative based on our previous somatic mutation analyses [12, 13]. The adjacent normal adrenal tissue of the aforementioned APA was also included in the WES analysis. WES was performed using standard protocols in our Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments–compliant sequencing laboratory [21, 22]. A total of 500 ng of gDNA was sheared using a Covaris S2 to a peak target size of 250 base pairs (bp). Concentration of the fragmented DNA was carried out using AMPure beads, followed by end-repair, A-base addition, ligation of the Illumina-indexed adapters, and size selection on 3% Nusieve agarose gels (Lonza). Illumina index primers and AMPure beads were used to amplify and purify fragments between 300 and 350 bp. A total of 1 µg of the library was hybridized to the Agilent SureSelect Human All Exon v.4. The targeted exon fragments were captured and enriched following the manufacturer’s protocol (Agilent). Analysis of the paired-end whole-exome libraries was performed by the Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer and DNA 1000 reagents, and sequencing was performed with the Illumina HiSeq 2500 sequencing system (Illumina Inc). The primary base call files were converted into FASTQ sequence files using the bcl2fastq converter tool bcl2fastq-1.8.4 in the CASAVA 1.8 pipeline.

F. Ion Torrent-Based Targeted Amplicon Sequencing

Validation of the CLCN2 variant identified by WES and molecular profiling of the mutation-negative APAs was carried out by targeted amplicon sequencing using custom AmpliSeq panels and the Ion Torrent System (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Targeted regions included the complete coding sequences of KCNJ5, CACNA1D, CACNA1H, ATP1A1, ATP2B3, CLCN2, and PRKACA as well as oncogenic hotspot regions of GNAS and CTNNB1. Library preparation, DNA sequencing, and identification of the somatic variants were performed as described previously [12, 14, 23].

G. Sanger Sequencing

Further validation of the CLCN2 mutation status was performed by direct bidirectional Sanger sequencing of CLCN2 of APA-adjacent normal tissue pairs. The gDNA in APA-adjacent normal tissue pairs was sequenced following PCR amplification using specific primers: forward: 5’-CCTGGGAGAAGAGGAGTGGAG-3’; and reverse: 5’-GCTCTAATGGCCTCTGCTTC-3’.

2. Results

A. Identification of Somatic CLCN2 Mutations in Aldosterone-Producing Adenomas

WES was performed on FFPE gDNA from one APA (APA_UM16) that tested negative for the presence of any of the known APA-related somatic mutations using CYP11B2 IHC-guided targeted amplicon sequencing. gDNA was selectively isolated from both the CYP11B2-expressing region (APA) and the adjacent normal tissue (as a control) and used for somatic variant calling and copy number analysis. While a total of 132 935 004 reads (89.1% alignment to hg19 reference genome) were obtained from the tumor sample for an effective average coverage of 187× per base, a total of 68 301 691 reads (87.8% alignment to hg19 reference genome) provided an effective coverage of 126× per base for the matched normal sample. No notable copy-number variation was observed. A somatic mutation in CLCN2 (c.G71A, p.G24D, NM_004366) was identified specifically in the tumor (Table 1). In addition to the CLCN2 variant, the results also identified 10 other putative somatic mutations in this tumor (Table 2).

Table 1.

Results of whole-exome sequencing

| NGS ID | Gene | Type | Base change | Amino acid change | Exon | Ref seq | VF (tumor) | VF (normal) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| APA_UM16 | CLCN2 | Missense | c.G71A | p.G24D | 2 | NM_004366 | 52/174 (30%) | 0/76 (0%) |

Abbreviations: APA, aldosterone-producing adenoma; ID, identification; NGS, next-generation sequencing; Ref, reference; seq, sequence; VF, variant allele frequency.

Table 2.

Potential somatic mutations in APA_UM16 after whole-exome sequencing

| No. | Chr | Position | Validated by Sanger sequencing | Validated by targeted amplicon sequencing | Gene | Type | Amino acid change | VF (tumor) | VF (normal) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 3 | 184076912 | Yes | Yes | CLCN2 | Missense | p.G24D | 52/174 (30%) | 0/76 (0%) |

| 2 | 3 | 173996717 | No | No | NLGN1 | Missense | p.P309L | 15/62 (24%) | 0/57 (0%) |

| 3 | 14 | 20876109 | No | No | TEP1 | Frameshift | p.K164fs | 8/82 (10%) | 0/65 (0%) |

| 4 | 9 | 131020795 | No | No | GOLGA2 | Disruptive_Inframe_Deletion | p.Glu715del | 15/117 (13%) | 0/47 (0%) |

| 5 | 14 | 23549878 | No | No | ACIN1 | Disruptive_Inframe_Deletion | p.Glu280del | 8/80 (10%) | 1/67 (1%) |

| 6 | 2 | 67631670 | No | No | ETAA1 | Inframe_Deletion | p.Leu649_Lys677del | 7/81 (9%) | 0/63 (0%) |

| 7 | 3 | 158450159 | No | No | RARRES1 | Start_Lost and Inframe_Deletion | p.Met1_Pro15del | 6/109 (6%) | 0/67 (0%) |

| 8 | 3 | 130743760 | No | No | ASTE1 | Missense | p.Arg131Trp | 6/94 (6%) | 0/8 2(0%) |

| 9 | 17 | 42756274 | No | No | CCDC43 | Missense | p.Arg209Cys | 6/113 (5%) | 0/87 (0%) |

| 10 | 22 | 40391306 | No | No | FAM83F | Inframe_Deletion | p.Lys92_Ala93del | 10/197 (5%) | 0/134(0%) |

| 11 | 1 | 8716291 | No | No | RERE | Disruptive_Inframe_Deletion | p.Asp18_Arg21del | 6/119 (5%) | 0/86 (0%) |

Abbreviations: APA, aldosterone-producing adenoma; Chr, chromosome; VF, variant allele frequency.

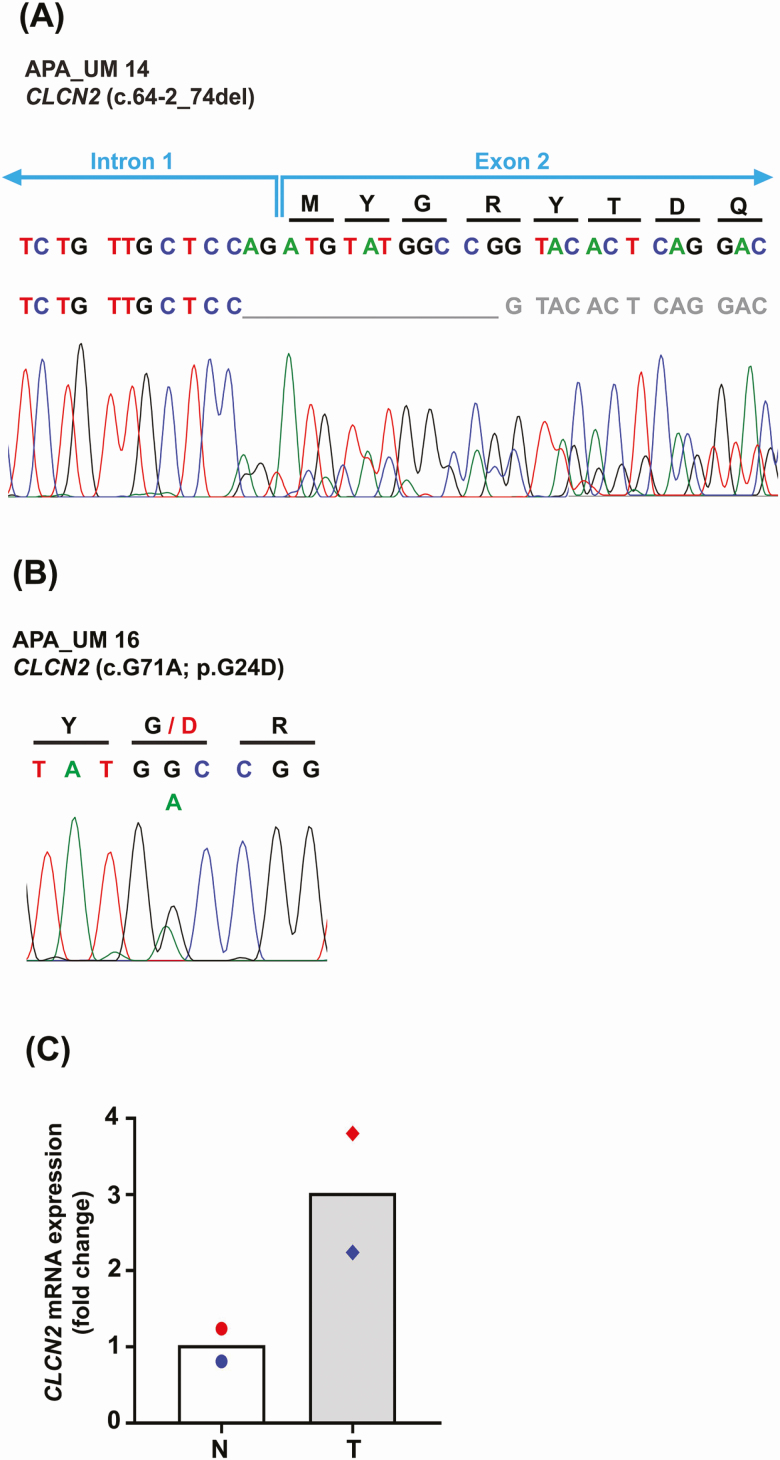

B. Prevalence of Somatic CLCN2 Mutations in Aldosterone-Producing Adenomas

To screen for additional CLCN2 somatic mutations in APAs, targeted amplicon sequencing was performed with a newly developed gene panel on a set of 10 APAs that were CYP11B2-positive but did not show the existence of any of the common somatic mutations [12]. Out of the 10 APAs, 1 APA (APA_UM14) harbored a novel somatic CLCN2 mutation (c.64-2_74del) (Table 3), which was confirmed by Sanger sequencing (Fig. 1). The presence of the somatic CLCN2 p.G24D mutation identified by WES in APA_UM16 was also corroborated by targeted amplicon sequencing (Table 3) and Sanger sequencing (Fig. 1). No evidence of the variants was observed in the adjacent normal adrenal tissue by Sanger sequencing confirming the somatic nature of these mutations. CLCN2 mRNA levels demonstrated an increasing trend in expression in both APAs vs their respective adjacent normal adrenal tissue by qPCR. However, owing to the presence of only 2 APA samples, statistical analysis was not performed. The sequencing results demonstrated an overall prevalence of 1.74% (2/115) CLCN2 somatic mutations in American PA patients. Baseline clinical characteristics of PA patients with somatic CLCN2 mutations are summarized in Table 4.

Table 3.

Results of ion torrent-based targeted amplicon sequencing

| NGS ID | Gene | Type | Reference allele | Variant allele | Base change | Amino acid change | FDP | VF (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| APA_UM14 | CLCN2 | Frameshift deletion | CCGGCCATACATCT | – | c.64-2_74del | – | 1518 | 39 |

| APA_UM16 | CLCN2 | Missense | C | T | c.G71A | p.G24D | 2000 | 33 |

No evidence of the variants was found in the adjacent normal adrenal tissue by Sanger sequencing or targeted amplicon sequencing.

Abbreviations: APA, aldosterone-producing adenoma; FDP, flow-corrected read depth; ID, identification; NGS, next-generation sequencing; VF, variant allele frequency.

Figure 1.

A and B, Results of Sanger sequencing of CYP11B2-expressing tumor region for both aldosterone-producing adenomas (APAs) harboring somatic CLCN2 mutations. The top row of nucleotides denotes the nucleotide trace in the matched normal adjacent adrenal tissue obtained by Sanger sequencing. The variant in APA_UM14 (c.64-2_74del) suggests a splice site deletion mutation. C, Quantitative reverse transcriptase–polymerase chain reaction analysis for expression of CLCN2 messenger RNA levels in tumor (T) vs their respective adjacent normal tissue (N). Results are indicated as mean. Red and blue symbols indicate the N-T pair for APA_UM14 and APA_UM16, respectively.

Table 4.

Clinical characteristics of patients with CLCN2-mutated aldosterone-producing adenoma

| Age, y | Sex | Race | NGS ID | BP, mm Hg | No. of antihypertensive medications | Serum K+, mEq/L | K+ supplementation | PAC, ng/ dL | PRA, ng/ mL/h | Tumor size on imaging study, mm | Side of adrenal tumor | Side of aldosterone excess by AVS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 63 | M | White | APA_UM14 | 154/98 | 5 | 2.1 | Yes | 51 | 0.1 | 16 | Right | Right |

| 48 | F | White | APA_UM16 | 174/82 | 3 | 3.1 | Yes | 31 | 0.5 | 6 | Left | Left |

Abbreviations: APA, aldosterone-producing adenoma; AVS, adrenal venous sampling; BP, blood pressure; F, female; ID, identification; K+, potassium; M, male; NGS, next-generation sequencing; PAC, plasma aldosterone concentration; PRA, plasma renin activity.

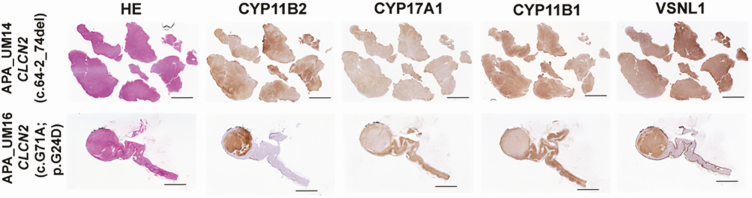

C. Histological Characteristics of Somatic CLCN2 Mutations in Aldosterone-Producing Adenomas

Whereas APA_UM16 demonstrated a few lipid-rich regions within the tumor, APA_UM14 showed the presence of mostly compact cells (Fig. 2). Both tumors showed positive CYP11B2 expression throughout the tumor (see Fig. 2). The CYP11B2 immunoreactivity varied from low to high with no negative regions. The expression of CYP17A1 was observed to vary from low to moderate, whereas that of CYP11B1 varied from moderate to high. Interestingly, some regions in the APAs demonstrated coexpression of CYP11B2 and CYP17A1. VSNL1 (a marker for the zona glomerulosa) [24, 25] demonstrated increased immunoreactivity in both tumors vs their respective adjacent normal tissue (see Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Histopathologic characteristics of aldosterone-producing adenomas (APAs) with somatic CLCN2 mutations. Scanned images of the tumors following hematoxylin and eosin staining, and aldosterone synthase (CYP11B2), 17α-hydroxylase/17,20 lyase (CYP17A1), rat monoclonal antibody against human 11β-hydroxylase (CYP11B1), and visinin-like 1 (VSNL1) immunohistochemistry. Scale: 5 mm.

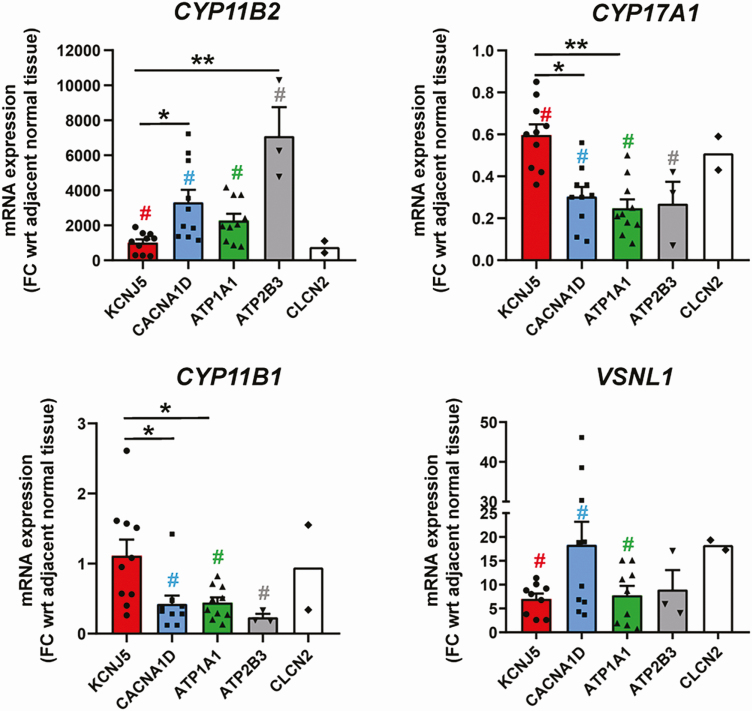

D. Comparison of Messenger RNA Transcript Levels of Steroidogenic Enzyme Genes Among Aldosterone-Producing Adenomas With Different Somatic Mutations

mRNA transcript levels of key steroidogenic enzyme genes such as CYP11B2, CYP17A1, and CYP11B1 were compared between APAs harboring somatic mutations in KCNJ5 (n = 10), CACNA1D (n = 10), ATP1A1 (n = 10), ATP2B3 (n = 3), and CLCN2 (n = 2) (Fig. 3). Statistical analysis was not performed for the CLCN2 APA and their respective adjacent normal tissue samples because of the low sample number. Whereas CYP11B2 expression showed a substantial increase in all types of tumors vs matched normal adrenal tissue, CYP17A1 transcript levels demonstrated a significant drop in the tumor tissue (P < .05). Of all APAs, those harboring mutations in ATP2B3, CACANA1D, and ATP1A1 demonstrated the highest CYP11B2 expression (P < .05). Inversely, APAs with KCNJ5 mutations displayed the most abundant CYP17A1 transcript levels among all APA subtypes (P < .05). APAs harboring the CLCN2 mutation showed the least increase in CYP11B2 mRNA levels when compared to other APA subtypes, but their CYP17A1 expression was comparable to APAs with KCNJ5 mutations. CYP11B1 mRNA transcripts showed an expression trend similar to that of CYP17A1. Transcript levels of VSNL1 were also demonstrated to be higher in all tumors vs the matched normal tissue.

Figure 3.

Quantitative reverse transcriptase–polymerase chain reaction analysis for comparison of key steroidogenic enzymes (aldosterone synthase [CYP11B2], 17α-hydroxylase/17,20 lyase [CYP17A1], and rat monoclonal antibody against human 11β-hydroxylase [CYP11B1]) as well as visinin-like 1 (VSNL1) among aldosterone-producing adenomas with different somatic mutations (KCNJ5, CACNA1D, ATP1A1, ATP2B3, CLCN2). Results are indicated as mean ± SEM. #P less than .05 for tumor (T) vs respective adjacent normal tissue (N). *P less than .05; **P less than .005. mRNA, messenger RNA.

3. Discussion

The advent of NGS in the last decade has been instrumental in elucidating the somatic genetic landscape pathogenesis of both sporadic and familial PA to a great extent. A majority of the PA-causing somatic and germline variants have been shown to lead to excess aldosterone production via increased CYP11B2 expression due to disrupted intracellular Ca2+ signaling. Previous studies using grossly dissected pathology-provided snap-frozen APA tumor tissue were not able to identify aldosterone-driver mutations in more than 45% of APA [26]. We applied a first-in-field sequencing approach by using FFPE tissue for CYP11B2 IHC-guided DNA capture of APA. This was followed by targeted amplicon sequencing of genes frequently mutated in familial and sporadic PA. This strategy improved the detection rate of known somatic mutations to more than 90% and identified novel somatic mutations that are likely causing autonomous aldosterone production in APA [12, 13]. The present study used CYP11B2 IHC-guided WES and targeted NGS and identified 2 somatic mutations (c.G71A;p.G24D and c.64-2_74del) in CLCN2 in 2 different APAs. The presence of these variants in 2 tumors suggests that CLCN2 mutations as a cause of APAs are rare, with an approximate prevalence of 1.74% (2/115 APAs).

The CLCN2 gene is located on chromosome 3q27 and encodes ClC-2, an inwardly rectifying chloride channel, a member of the CLC voltage-gated Cl– channels family. Two studies have shown that this channel is expressed in the human adrenal cortex [27, 28]. Several germline CLCN2 variants have been reported in PA patients [27, 28]. This condition is known as FH type II, which was first described by Richard Gordon and Michael Stowasser in the early 1990s [29, 30]. Scholl et al studied the original kindred first described by Stowasser in 2018 and identified a gain-of-function early-onset germline variant in CLCN2 (p.R172Q) [28], in addition to 4 new rare germline CLCN2 variants (p.M22K, p.Y26N, p.K362del, and p.S865R) [28]. Concurrently, Fernandes-Rosa and colleagues identified a de novo germline CLCN2 mutation in a 9-year-old patient (p.G24D) [27] that was similar to the somatic APA mutation recently described by Dutta et al [31] as well as one of the somatic mutations reported in our study. Both groups performed functional studies wherein electrophysiological experiments in H295R-S2 and HEK293 cells transfected with wild-type and mutant CLCN2 demonstrated that the mutations caused increased activation of the Cl– channels leading to depolarization of the cell membrane and subsequent opening of the voltage-dependent Ca2+ channels, confirming a gain-of-function mechanism. The consequential rise in cytoplasmic Ca2+ leads to upregulation of CYP11B2 and increased aldosterone biosynthesis [27, 28]. Recent mouse models expressing an open ClC-2 Cl− channel (Clcn2op) [32] and a heterozygous Clcn2 mutation (Clcn2R180Q/+) at the location homologous to the p.R172Q mutation in humans [33] also demonstrated a PA phenotype.

The main limitation of our study is the lack of the functional characterization of the new c.64-2_74del variant. The variant destroys the consensus slice acceptor site at the IVS1/exon2 boundary in the reference sequence. The impact on translation is unclear, but there are several predicted scenarios of either skipping exon 2, using a different intronic splice site, or a newly generated cryptic splice site within exon 2. The exon 2 skipping scenario would generate a frameshift mutation leading to an early stop codon, whereas the other 2 scenarios would produce a mutant protein with stretches of different amino acids and/or short deletions, but keep the original reading frame in the majority of exon 2 and beyond. Interestingly, both the latter scenarios would lead to deletion of glycine 24—an apparent mutation hotspot for PA. Further in vitro studies will be required to determine transcript variants and whether they increase aldosterone production by activation gain-of-function of the Cl– channels thereby disrupting cellular Ca2+ signaling and increasing CYP11B2 expression. The other caveat of this study is the absence of steroid analysis from patient serum. However, intriguingly, both the APAs harboring the CLCN2 mutations showed comparable expression of CYP11B2, CYP17A1, and CYP11B1 as that seen in KCNJ5 mutation-expressing APAs. Hence, it is likely that the patients with APAs harboring CLCN2 mutations might produce the ‘hybrid’ 18-oxysteroids [34-36].

In conclusion, we identified 2 somatic CLCN2 mutations in a subset of APAs. One of the CLCN2 mutations (c.G71A, p.G24D) was identical to that previously found to cause germline early-onset PA and a sporadic APA. The second CLCN2 mutation, affecting the same coding region, is a new APA-associated mutation (c.64-2_74del). The molecular mechanisms of somatic CLCN2 mutations causing APA formation and steroid profiling of patients harboring these mutations, however, need to be further investigated.

Acknowledgments

We thank Michelle Vinco and Farah Keyoumarsi at the University of Michigan for assistance in slide preparation. We are also thankful to Marcin Cieslik, Fengyun Su, Rui Wang, Xuhong Cao, and Arul M. Chinnaiyan at the University of Michigan for whole-exome sequencing.

Financial Support: This work was supported by the American Heart Association (Grant 17SDG33660447 to K.N.), National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (Grant DK106618 to W.E.R.), and the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (Grant HL130106 to T.E.).

Glossary

Abbreviations

- APA

aldosterone-producing adenoma

- Ca2+

calcium

- CYP11B1

11β-hydroxylase

- CYP11B2

aldosterone synthase

- CYP17A1

17α-hydroxylase/17,20 lyase

- FH

familial hyperaldosteronism

- FFPE

formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded

- IHC

immunohistochemistry

- mRNA

messenger RNA

- NGS

next-generation sequencing

- PA

primary aldosteronism

- VSNL1

visinin-like 1

- WES

whole-exome sequencing

Additional Information

Disclosure Summary: The authors have nothing to disclose.

Data Availability

The data sets generated during and/or analyzed during the present study are not publicly available but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

- 1. Funder JW, Carey RM, Mantero F, et al. The management of primary aldosteronism: case detection, diagnosis, and treatment: an Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2016;101(5):1889-1916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Sinclair AM, Isles CG, Brown I, Cameron H, Murray GD, Robertson JW. Secondary hypertension in a blood pressure clinic. Arch Intern Med. 1987;147(7):1289-1293. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Rossi GP, Barisa M, Belfiore A, et al. ; PAPY study Investigators The aldosterone-renin ratio based on the plasma renin activity and the direct renin assay for diagnosing aldosterone-producing adenoma. J Hypertens. 2010;28(9):1892-1899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Mulatero P, Stowasser M, Loh KC, et al. Increased diagnosis of primary aldosteronism, including surgically correctable forms, in centers from five continents. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004;89(3):1045-1050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Funder JW, Carey RM, Fardella C, et al. ; Endocrine Society Case detection, diagnosis, and treatment of patients with primary aldosteronism: an endocrine society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008;93(9):3266-3281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Rossi GP, Bernini G, Caliumi C, et al. ; PAPY Study Investigators A prospective study of the prevalence of primary aldosteronism in 1125 hypertensive patients. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;48(11):2293-2300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Young WF., Jr Minireview: primary aldosteronism—changing concepts in diagnosis and treatment. Endocrinology. 2003;144(6):2208-2213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Choi M, Scholl UI, Yue P, et al. K+ channel mutations in adrenal aldosterone-producing adenomas and hereditary hypertension. Science. 2011;331(6018):768-772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Azizan EAB, Poulsen H, Tuluc P, et al. Somatic mutations in ATP1A1 and CACNA1D underlie a common subtype of adrenal hypertension. Nat Genet. 2013;45(9):1055-1060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Beuschlein F, Boulkroun S, Osswald A, et al. Somatic mutations in ATP1A1 and ATP2B3 lead to aldosterone-producing adenomas and secondary hypertension. Nat Genet. 2013;45(4):440-444, 444.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Scholl UI, Goh G, Stölting G, et al. Somatic and germline CACNA1D calcium channel mutations in aldosterone-producing adenomas and primary aldosteronism. Nat Genet. 2013;45(9):1050-1054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Nanba K, Omata K, Else T, et al. Targeted molecular characterization of aldosterone-producing adenomas in white Americans. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2018;103(10):3869-3876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Nanba K, Omata K, Gomez-Sanchez CE, et al. Genetic characteristics of aldosterone-producing adenomas in blacks. Hypertension. 2019;73(4):885-892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Nanba K, Chen AX, Omata K, et al. Molecular heterogeneity in aldosterone-producing adenomas. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2016;101(3):999-1007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. RRID:AB_2783793. ProMED-mail website. https://scicrunch.org/resolver/AB_2783793. [Google Scholar]

- 16. RRID:AB_2832208. ProMED-mail website. https://scicrunch.org/resolver/AB_2832208. [Google Scholar]

- 17. RRID:AB_2650563. ProMED-mail website. https://scicrunch.org/resolver/AB_2650563. [Google Scholar]

- 18. RRID:AB_2857939. ProMED-mail website. https://scicrunch.org/resolver/AB_2857939. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Pezzi V, Mathis JM, Rainey WE, Carr BR. Profiling transcript levels for steroidogenic enzymes in fetal tissues. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2003;87(2-3):181-189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Bassett MH, Mayhew B, Rehman K, et al. Expression profiles for steroidogenic enzymes in adrenocortical disease. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005;90(9):5446-5455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Robinson DR, Wu YM, Lonigro RJ, et al. Integrative clinical genomics of metastatic cancer. Nature. 2017;548(7667):297-303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Robinson D, Van Allen EM, Wu YM, et al. Integrative clinical genomics of advanced prostate cancer. Cell. 2015;162(2):454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Nishimoto K, Tomlins SA, Kuick R, et al. Aldosterone-stimulating somatic gene mutations are common in normal adrenal glands. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015;112(33):E4591-E4599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Trejter M, Hochol A, Tyczewska M, et al. Visinin-like peptide 1 in adrenal gland of the rat. Gene expression and its hormonal control. Peptides. 2015;63:22-29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Williams TA, Monticone S, Crudo V, Warth R, Veglio F, Mulatero P. Visinin-like 1 is upregulated in aldosterone-producing adenomas with KCNJ5 mutations and protects from calcium-induced apoptosis. Hypertension. 2012;59(4):833-839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Fernandes-Rosa FL, Williams TA, Riester A, et al. Genetic spectrum and clinical correlates of somatic mutations in aldosterone-producing adenoma. Hypertension. 2014;64(2):354-361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Fernandes-Rosa FL, Daniil G, Orozco IJ, et al. A gain-of-function mutation in the CLCN2 chloride channel gene causes primary aldosteronism. Nat Genet. 2018;50(3):355-361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Scholl UI, Stölting G, Schewe J, et al. CLCN2 chloride channel mutations in familial hyperaldosteronism type II. Nat Genet. 2018;50(3):349-354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Gordon RD, Stowasser M, Tunny TJ, Klemm SA, Finn WL, Krek AL. Clinical and pathological diversity of primary aldosteronism, including a new familial variety. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 1991;18(5):283-286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Stowasser M, Gordon RD, Tunny TJ, Klemm SA, Finn WL, Krek AL. Familial hyperaldosteronism type II: five families with a new variety of primary aldosteronism. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 1992;19(5):319-322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Dutta RK, Arnesen T, Heie A, et al. A somatic mutation in CLCN2 identified in a sporadic aldosterone-producing adenoma. Eur J Endocrinol. 2019;181(5):K37-K41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Göppner C, Orozco IJ, Hoegg-Beiler MB, et al. Pathogenesis of hypertension in a mouse model for human CLCN2 related hyperaldosteronism. Nat Commun. 2019;10(1):4678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Schewe J, Seidel E, Forslund S, et al. Elevated aldosterone and blood pressure in a mouse model of familial hyperaldosteronism with ClC-2 mutation. Nat Commun. 2019;10(1):5155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Mulatero P, di Cella SM, Monticone S, et al. 18-hydroxycorticosterone, 18-hydroxycortisol, and 18-oxocortisol in the diagnosis of primary aldosteronism and its subtypes. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;97(3):881-889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Tezuka Y, Yamazaki Y, Kitada M, et al. 18-Oxocortisol synthesis in aldosterone-producing adrenocortical adenoma and significance of KCNJ5 mutation status. Hypertension. 2019;73(6):1283-1290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Lenders JWM, Williams TA, Reincke M, Gomez-Sanchez CE. Diagnosis of endocrine disease: 18-oxocortisol and 18-hydroxycortisol: is there clinical utility of these steroids? Eur J Endocrinol. 2018;178(1):R1-R9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data sets generated during and/or analyzed during the present study are not publicly available but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.