Abstract

The meniscus is an essential structure for the knee functioning and survival. Meniscectomy is the most common surgical procedure in orthopaedic surgery. Following total or subtotal meniscectomy, meniscal allograft transplantation (MAT) should be considered in symptomatic active young patients. Several MAT techniques have been described in the literature as an attempt to restore normal knee kinematics and potentially decrease the risk of developing knee osteoarthritis. The purpose of this article is to describe in detail an efficient and reproducible all-arthroscopic MAT technique with bone plugs and preloaded sutures.

Meniscal tears are the most frequently encountered and treated injuries in the knee joint. Similarly, arthroscopic partial meniscectomy is one of the most commonly performed procedures in orthopedics.1,2 The menisci play an important role in shock absorption, load distribution, knee stability, joint lubrication, and congruity. Meniscal deficiency can compromise the future of the knee by leading to premature, progressive osteoarthritis.3,4

In 1948, T. J. Fairbank was the first to describe radiographic degenerative changes following meniscectomy and emphasized the importance of the meniscus in protecting the articular cartilage and joint.4 In addition, numerous studies have elucidated the importance of the meniscus retain, repair, or replacement (meniscal scaffold or meniscal allograft transplantation) to maintain knee joint homeostasis.5, 6, 7 Whenever feasible, retention or repair must be prioritized to prevent from the deleterious effect of partial, subtotal, or total meniscectomy. In instances where preservation of the native meniscus is no longer a feasible option, meniscal allograft transplantation (MAT) and implants or scaffolds may be considered. Only when a meniscal tear is considered irreparable or has no healing capacity, minimal or partial resection of the torn portion is indicated in the presence of limiting refractory mechanical symptoms.6, 7, 8, 9

A variety of factors should be considered when evaluating a potential candidate for MAT as a joint preservation strategy. The ideal candidate for MAT is a patient younger than 55 years of age; with a previous subtotal, total, or a functionally equivalent meniscectomy; no severe degenerative changes and joint instability; presents with joint line pain in the meniscus-deficient compartment; and shows neutral alignment. Indications and contraindications for MAT are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Indications and Contraindications for the Meniscal Allograft Transplantation

| Indications | Contraindications |

|---|---|

|

|

Once a patient has been deemed appropriate for MAT, the surgeon must ensure an adequate graft is available. Preservation and sterilization methods of the meniscal allografts appear to play a role in outcome. There are 4 primary types of allografts available when performing a MAT: fresh-viable, fresh-frozen or deep-frozen, cryopreserved, and lyophilized or freeze-dried. Lyophilization is not currently used anymore because of increased risk of meniscal shrinkage. Cryopreserved and fresh-frozen allografts are the most commonly used. Cryopreservation is believed to preserve the most relevant meniscal ultrastructure despite the preservation of cellular viability being less reliable. Fresh-frozen is simple and relatively cheap, it reasonably preserves the collagen architecture.10, 11, 12

The currently described techniques for MAT are open or arthroscopically assisted, but the latter is more commonly used. The meniscus allograft needs firm attachment and peripheral fixation. Fixation of the meniscal roots may be achieved either by using suture anchors, suturing the horns through tibial bone tunnels or using bony fixation (bone plugs or bone bridge).13, 14, 15, 16 Peripheral fixation of the allograft has been traditionally achieved by all-inside, outside-in, or inside-out suturing techniques.13

The purpose of this Technical Note article is to describe an all-arthroscopic MAT surgical technique with bone plugs adding preloaded vertical meniscal sutures and direct posterior horn fixation.

Surgical Technique

Meniscal Allograft Preparation

A meniscal allograft with tibial plateau is obtained from a national tissue bank, matching for the patient height, weight, and sex because it has been demonstrated to accurately predict proper meniscal allograft dimensions.17 The meniscal fresh-frozen allograft is prepared by an assistant on the back table (Video 1).

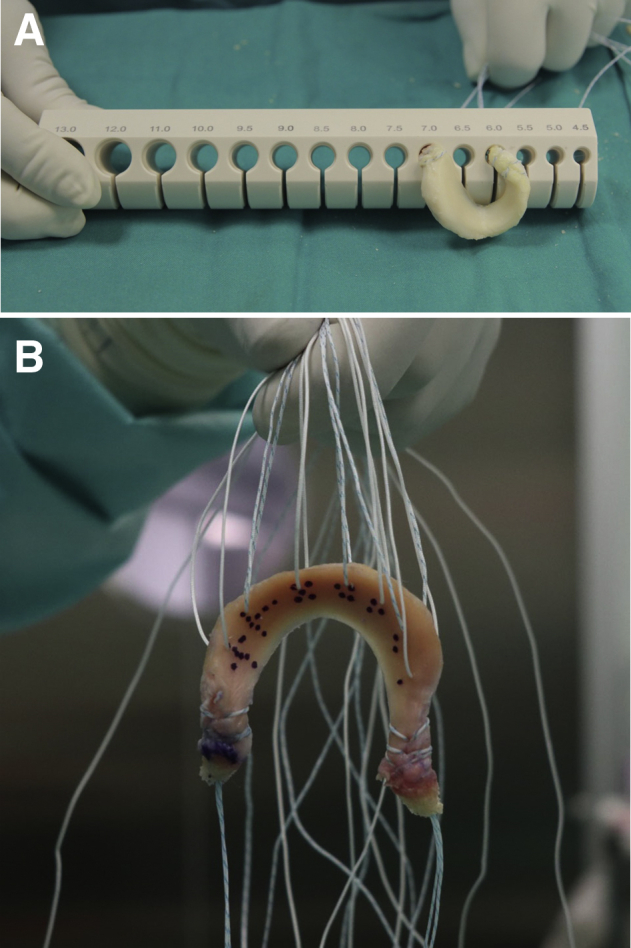

The bone blocks are trimmed of excess bone and soft tissue with a saw, bone rongeur, and scissors. This allows for a better fit on the anterior and posterior meniscal root attachments. Ideally, we aim for a truncated cone shape in our plugs, with 6.0 to 7.0 mm and 7.0 to 8.0 mm in diameter for the anterior and posterior meniscal root bone blocks, respectively (Fig 1). Next, a 2-mm central hole is drilled in each bone block, and a No. 2 high-strength looped suture with straight needle is used to whipstitch 2 to 3 times the horn before it is passed through the central hole of the bone block for correct pulling (Table 2). The meniscal allograft is then marked with a marking pen to locate the precise spots for the 6 to 8 preloaded vertical meniscal sutures high strength sutures (Ultrabraid No. 2, Smith & Nephew, Massachusetts, USA), which will be used for fixing the meniscus to the meniscal remnant. It is recommended to alternate color sutures to facilitate suture recovering in the right sequence intraoperatively.

Fig 1.

Meniscal allograft with bone plugs and preloaded vertical sutures. (A) Proper measurement of the anterior and posterior meniscal root bone blocks. (B) Meniscal allograft is marked with a marking pen for placement of the preloaded vertical sutures (suture color should alternate to facilitate suture recovering sequence).

Table 2.

Pearls and Pitfalls of the All-Arthroscopic Meniscal Allograft Transplantation Technique With Bone Plugs and Preloaded Sutures

| Pearls | Pitfalls |

|---|---|

|

|

Meniscal Remnant Preparation

The surgical procedure is performed with the patient supine on the operating table and placed under general or regional anesthesia. A high-thigh tourniquet is placed on the operative limb and then it is placed into a single leg holder. A diagnostic arthroscopy evaluation of the joint is performed, inspecting for meniscal extrusion. A combination of meniscal biters and shavers are used to promote appropriate bleeding and to debride the remaining meniscal tissue, leaving a stable rim of 1 to 2 mm.

Posterior Root Tunnel

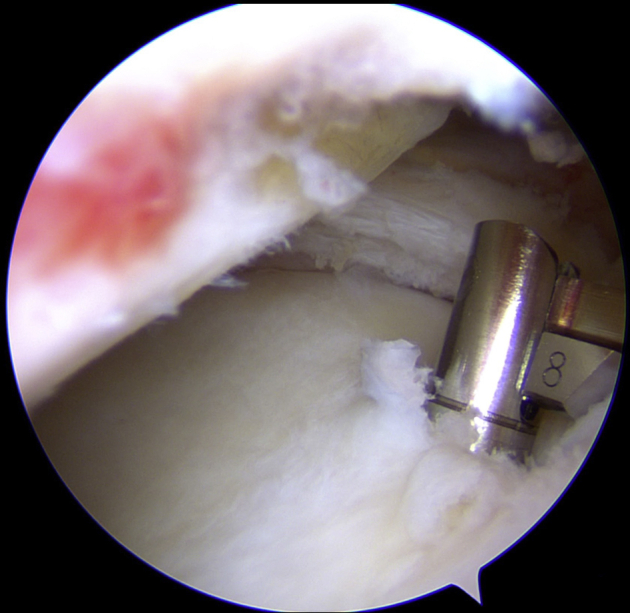

The bone tunnel for the posterior root attachment of the medial or lateral meniscus is created by retrograde (if available) drilling (FlipCutter II Drill (Arthrex) or ACUFEX TRUNAV Retrograde Drill (Smith & Nephew). A 45° angulated anterior cruciate ligament (ACL)/meniscal root tibial guide (ACL tibial guide ACUFEX PINPOINT vs root tibial guide, Smith & Nephew) is inserted through the ipsilateral anteromedial or anterolateral portal, respectively. It is recommended to increase the tunnel diameter by 0.5 mm to facilitate the entry of the bone block. The posterior medial meniscal root should be placed behind the medial tibial tubercle, in front of the posterior cruciate ligament tibial insertion site (Fig 2); the posterior lateral meniscal root should be placed behind the lateral tibial eminence meanwhile the camera is positioned in the contralateral anterior portal. A No. 1 PDS suture is then passed using a knot pusher through the tibial tunnel for later suture shuttling of the definitive posterior meniscal root threads.

Fig 2.

Intraoperative arthroscopic view of the retrograde drilling bone tunnel for posterior meniscal root fixation of the left knee. The diameter of the drill should have 0.5 mm more than the diameter of the bone plug.

Meniscal Allograft Insertion

Before the meniscal graft is inserted into the knee, 1 or preferably 2 of the preloaded sutures from the posterior horn must be passed through the posterior meniscal rim from bottom to top (for later meniscal posterior horn fixation.) A suture passer device (FIRSTPASS, Smith & Nephew) with the preloaded inferior end suture from posterior horn is used via the ipsilateral anteromedial or anterolateral portal. Next, 2 spinal needles are passed outside-in vertically in the posteromedial (medial meniscal transplant) or posterolateral (lateral meniscal transplant) angle of the meniscal rim using 2 No. 1 PDS sutures to shuttle the preloaded suture of the meniscal posteromedial or posterolateral angle. These threads located in the corner of the knee are very important during the meniscal allograft insertion. The meniscal allograft transplant is directed inside the knee through an ipsilateral enlarged portal while pulling on the posterior root meniscal sutures and the sutures located in the knee angle. Once the meniscal allograft is adequately balanced inside the knee, the posterior horn meniscal sutures are tied down using a knot pusher from an accessory anterior portal.

Peripheral Fixation

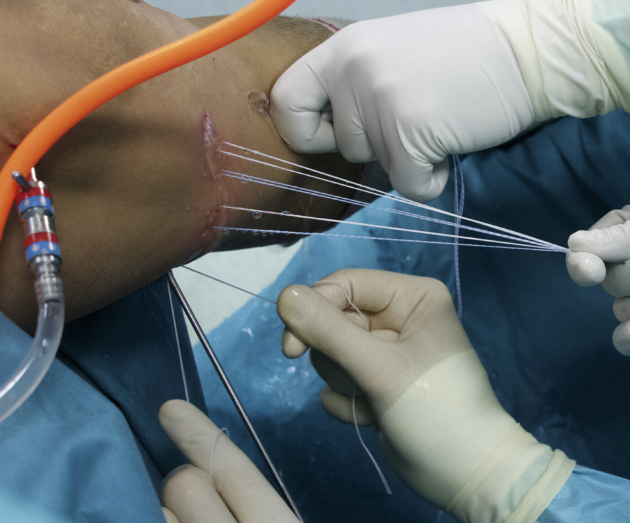

A piercing suture retriever (Acufex arthropierce suture retriever, Smith & Nephew) is then used to collect all the preloaded meniscal sutures from the meniscal body and anterior horn. The preloaded meniscal sutures should be retrieved by the assistant sequentially from posterior to anterior. At the same time, visualization is optimized by the surgeon using a probe to create space in between the meniscal graft wall and the capsule (Fig 3).

Fig 3.

External view of the peripheral preloaded sutures of the meniscal allograft after passing through the meniscal rim.

Anterior Root Tunnel

The anterior root tunnel should be created after insertion of the posterior meniscal root bone plug and retrieval of all preloaded sutures. This sequence allows us to have a more accurate idea about the precise location. Ideally, we should look for the anatomic anterior horn insertion. The anterior horn footprint of the medial meniscus is located in front of the tibial insertion of ACL behind the intermeniscal ligament. The lateral anterior meniscal horn insertion can be found in front of the lateral eminence.

Suture Tightening

The peripheral stitches are tightened and tied from outside, as close as possible to the external capsule, generally from posterior to anterior and preferably using a knot-pusher (Fig 4). If needed, 2 or 3 all-inside meniscal sutures (FAST-FIX 360 Meniscal Repair, Smith & Nephew) are used to reinforce the posterior horn attachment from above or below (Fig 5).

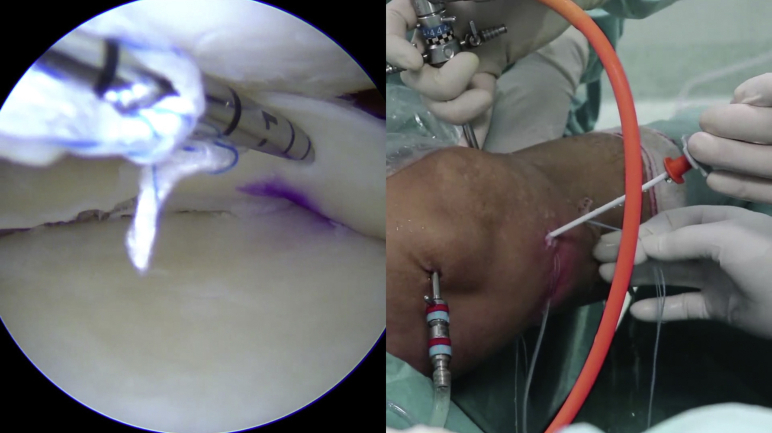

Fig 4.

Suture tightening from outside, generally from posterior to anterior with a knot-pusher.

Fig 5.

Arthroscopic view (left) and external view (right) of the all-inside reinforcement of the attachment of the posterior horn of the meniscal allograft to the posterior meniscal rim (left knee).

The procedure ends with the anterior and posterior root fixation. These can be sutured to each other or fixed separately to the anterior tibia, with the use of buttons or knotless implants, while maintaining the knee in flexed position at 45°.

Postoperative Rehabilitation

Postoperatively, a knee brace must be worn at all times, only removing it twice a day for knee exercises, allowing flexion up to maximum 90° for the first 4 weeks. Isometric exercises begin within the first week. Weightbearing is not allowed until week 4 or 6. From 5 to 8 weeks, progressive flexion and assisted weightbearing is allowed. From 8 to 12 weeks, effort should be centered on increasing strength and achieving full range of motion in flexion and extension. From 12 weeks on, progression should be taken to unrestricted daily-living activities, avoiding weights, kneeling, or sports. After 6 months postoperatively, unrestricted activities are allowed.

Generally, for patients who have a meniscal transplant, we advise against high-impact sport activities.

Discussion

MAT is a safe and reliable surgical technique for appropriately indicated patients who are younger than 55 years of age, without knee instability and malalignment, following subtotal or total meniscectomy, but continue to experience joint line pain in the affected area.

The MAT technique has evolved since the 1980s, although several controversial issues remain related to MAT. The variability of the MAT procedures, allograft availability, complexity of the techniques, and a relatively high complication and reoperation rate make this procedure challenging and not universally accepted.

The technique presented in this article is an evolution of the original technique, arthroscopic meniscal transplant without bone plugs, described by Alentorn-Geli et al.16 in 2010 and established in our group since 2001. This technique has evolved to the current one described by G.S. within the article, introducing the aforementioned innovations.

Regarding the outcomes obtained with MAT in the literature, LaPrade et al.18 have shown significant pain reduction, decrease of activity-related effusion, and function improvement with an average follow-up of 2.5 years following MAT. Verdonk et al.19 reported a cumulative 74.2% and 69.8% survival rate for medial and lateral meniscal allografts respectively at 10 years. Searle et al.20 claim the need for a specific MAT scoring system to redefine “success” and “failure” and distinguish between “clinical failure” and “surgical failure” outcomes.

The specific technique described in this article is advantageous by providing an all-arthroscopic procedure instead of open or mini-open technique, either for medial or lateral meniscus. In addition, it uses bone plug fixation for the meniscal roots, which according to Sekiya et al.,21 improves outcomes and increases knee functionality compared to soft-tissue fixation methods. Rodeo22 found an 88% success rate for transplanted menisci using bone plugs and 47% for those who had soft-tissue fixation. According to Abat et al.,23 the suture-only fixation technique also leads to a higher degree of extrusion than bony fixation in MAT. Despite that, Kim et al.24 suggest that MAT with soft tissue is less complex and can still provide stable and secure graft fixation.

In our group, we have observed intraoperatively that using bone plugs and press-fit adjustment to tunnels increased the intrinsic stability of the horns fixation and were less susceptible to secondary stress caused by knee motion. Bone-to-bone healing has been demonstrated to be fast and reliable in ACL reconstruction.25 There is little information available on meniscus-to-bone healing; thus, our group opted to switch to bony fixation. If in the future the meniscal allograft root fails to heal, it could potentially translate into a biomechanical meniscal root like injury behavior and be equivalent to an absent meniscus.26,27

Two important innovations are presented in this article: first, the use of preloaded vertical sutures on the meniscal allograft and, second, the direct suture fixation of the posterior horn. Preloading vertical sutures on the meniscus have several advantages. It reduces potential damage intraoperatively during suture passing. Also, it provides a strong “manually tied” fixation of the meniscus to the capsule and a homogenous perpendicular force application to the circularly distributed collagen fibers of the meniscal transplant wall. Unlike the described fixation method, all-inside, outside-in, or inside-out peripheral fixation of the meniscus grabs mostly superiorly or inferiorly the meniscus wall. Partial fixation instead of the whole meniscal rim height leads to partial healing of the MAT, which ultimately could lead to subsequent surgery or transplant failure.

Another advantage is that this technique does not require many meniscal suturing devices decreasing the potential risk related to these implants. Second, and the most important contribution in this technique is the posterior horn fixation method using a direct suture passer device. It enables for strong manual knot tying of the posterior horn capturing the complete height of the posterior meniscal remnant and capsule.

In conclusion, the all-arthroscopic meniscal allograft transplantation technique with bone plugs and preloaded sutures is an efficient, reliable, and reproducible technique that potentially can improve clinical results, while reducing complication and failure rates of MAT.

Footnotes

The authors report the following potential conflicts of interest or sources of funding: G.S. reports personal fees from Smith & Nephew. R.C. and the Carcía Cugat Foundation report a grant from Smith & Nephew. Full ICMJE author disclosure forms are available for this article online, as supplementary material.

Supplementary Data

Description of the all-arthroscopic meniscal allograft transplantation (MAT) technique with bone plugs and preloaded sutures.

References

- 1.Baker B.E., Peckham A.C., Pupparo F., Sanborn J.C. Review of meniscal injury and associated sports. Am J Sports Med. 1985;13:1–4. doi: 10.1177/036354658501300101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Englund M., Guermazi A., Gale D. Incidental meniscal findings on knee MRI in middle-aged and elderly persons. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:1108–1115. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0800777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Allen P.R., Denham R.A., Swan A.V. Late degenerative changes after meniscectomy. Factors affecting the knee after operation. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1984;66:666–671. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.66B5.6548755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fairbank T.J. Knee joint changes after meniscectomy. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1948;30:664–670. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kopf S., Beaufils P., Hirschmann M.T., Rotigliano N., Ollivier M. Management of traumatic meniscus tears: The 2019 ESSKA meniscus consensus. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2020 doi: 10.1007/s00167-020-05847-3. 28:1177-1194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baratz M.E., Fu F.H., Mengato R. Meniscal tears: The effect of meniscectomy and of repair on intraarticular contact areas and stress in the human knee: A preliminary report. Am J Sports Med. 1986;14:270–274. doi: 10.1177/036354658601400405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Beaufils P., Becker R., Kopf S. Surgical management of degenerative meniscus lesions: The 2016 ESSKA meniscus consensus. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2017;25:335–346. doi: 10.1007/s00167-016-4407-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Beaufils P., Pujol N. Management of traumatic meniscal tear and degenerative meniscal lesions. Save the meniscus. Orthopaed Traumatol Surg Res. 2017;103:S237–S244. doi: 10.1016/j.otsr.2017.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Seil R., Becker R. Time for a paradigm change in meniscal repair: Save the meniscus! Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2016;24:1421–1423. doi: 10.1007/s00167-016-4127-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pereira H., Cengiz I.F., Gomes S. Meniscal allograft transplants and new scaffolding techniques. EFORT Open Rev. 2019;4:279–295. doi: 10.1302/2058-5241.4.180103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jiang D., Zhao L.H., Tian M., Zhang J.Y., Yu J.K. Meniscus transplantation using treated xenogeneic meniscal tissue: Viability and chondroprotection study in rabbits. Arthroscopy. 2012;28:1147–1159. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2012.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Samitier G., Alentorn-Geli E., Taylor D.C. Meniscal allograft transplantation. Part 2: Systematic review of transplant timing, outcomes, return to competition, associated procedures, and prevention of osteoarthritis. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2014;23:323–333. doi: 10.1007/s00167-014-3344-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gelber P.E., Verdonk P., Getgood A.M., Monllau J.C. Meniscal transplantation: State of the art. Journal ISAKOS. 2017;2:339–349. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dean C.S., Olivetto J., Chahla J., Serra Cruz R., LaPrade R.F. Medial meniscal allograft transplantation: The bone plug technique. Arthrosc Techniques. 2016;5:e329–e335. doi: 10.1016/j.eats.2016.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chahla J., Olivetto J., Dean C.S., Serra Cruz R., LaPrade R.F. Lateral meniscal allograft transplantation: The bone trough technique. Arthrosc Techniques. 2016;5:e371–e377. doi: 10.1016/j.eats.2016.01.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Alentorn-Geli E., Vázquez R.S., Balletbó M.G. Arthroscopic meniscal allograft transplantation without bone plugs. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2011;19:174–182. doi: 10.1007/s00167-010-1123-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Van Thiel G.S., Verma N., Yanke A., Basu S., Farr J., Cole B. Meniscal allograft size can be predicted by height, weight, and gender. Arthroscopy. 2009;25:722–727. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2009.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.LaPrade R.F., Wills N.J., Spiridonov S.I., Perkinson S. A prospective outcomes study of meniscal allograft transplantation. Am J Sports Med. 2010;38:1804–1812. doi: 10.1177/0363546510368133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Verdonk P.C., Demurie A., Almqvist K.F., Veys E.M., Verbruggen G., Verdonk R. Transplantation of viable meniscal allograft. Survivorship analysis and clinical outcome of one hundred cases. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2005;87:715–724. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.C.01344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Searle H., Asopa V., Coleman S., Mcdermott I. The results of meniscal allograft transplantation surgery: What is success? BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2020;21:159. doi: 10.1186/s12891-020-3165-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sekiya J.K., West R.V., Groff Y.J., Irrgang J.J., Fu F.H., Harner C.D. Clinical outcomes following isolated lateral meniscal allograft transplantation. Arthroscopy. 2006;22:771–780. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2006.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rodeo S.A. Meniscal allografts—where do we stand? Am J Sports Med. 2001;29:246–261. doi: 10.1177/03635465010290022401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Abat F., Gelber P.E., Erquicia J.I. Suture-only fixation technique leads to a higher degree of extrusion than bony fixation in meniscal allograft transplantation. Am J Sports Med. 2012;40:1591–1596. doi: 10.1177/0363546512446674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kim S.H., Lipinski L., Pujol N. Meniscal allograft transplantation with soft-tissue fixation including the anterior intermeniscal ligament. Arthrosc Techniques. 2020;9:e137–e142. doi: 10.1016/j.eats.2019.09.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Irvine J.N., Arner J.W., Thorhauer E. Is there a difference in graft motion for bone-tendon-bone and hamstring autograft ACL reconstruction at 6 weeks and 1 year? Am J Sports Med. 2016;44:2599–2607. doi: 10.1177/0363546516651436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Laprade C.M., Foad A., Smith S.D. Biomechanical consequences of a nonanatomic posterior medial meniscal root repair. Am J Sports Med. 2015;43:912–920. doi: 10.1177/0363546514566191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Forkel P., Herbort M., Schulze M. Biomechanical consequences of a posterior root tear of the lateral meniscus: Stabilizing effect of the meniscofemoral ligament. Arch Orthopaed Trauma Surg. 2013;133:621–626. doi: 10.1007/s00402-013-1716-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Description of the all-arthroscopic meniscal allograft transplantation (MAT) technique with bone plugs and preloaded sutures.