The coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic has crippled the United States, halting normal social and economic activities and overstretching the health system. As of June 12, 2020, the United States had over 2 million cases and 113,900 deaths (1). For historically disadvantaged populations, who experience fractured access to health care under standard conditions (2) and who are more dependent on low-wage or hourly paid employment (3), the pandemic has had a disproportionate impact. Reports from state and city health departments have illuminated what many already knew: Black, Latinx, and Native Americans test positive for and die of COVID-19 at higher proportion than other racial and ethnic groups (Figure 1) (1). In part as a consequence of the increased prevalence of COVID-19 in minority populations, the mortality rates among Black, Latinx, and Native Americans far exceeds the proportion of the population that these groups represent (1).

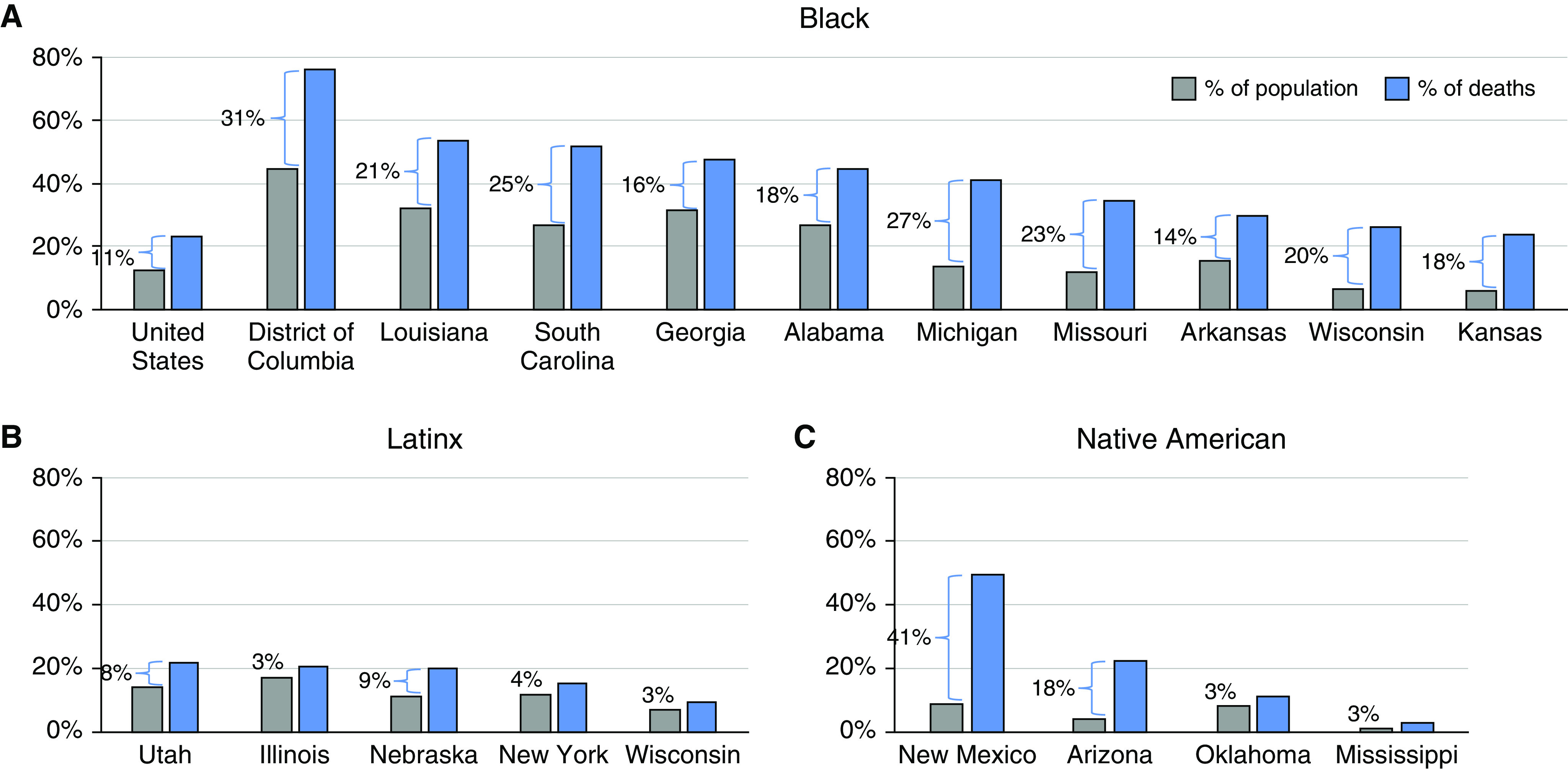

Figure 1.

Mortality due to coronavirus disease (COVID-19) compared with representation within the population in states with greatest disparities for (A) Black, (B) Latinx, and (C) Native American populations. Gray bars represent the percentage of minorities in the state, and blue bars represent the percentage of deaths within the state across minority groups. Data were collected from the CDC and are current through June 11, 2020.

Nearly 30% of COVID-19 cases occurred in Black Americans, who constitute only 13% of the U.S. population (1, 4). This pattern continues to be observed at the state level across states reporting the highest mortality from COVID-19 (1) and is paralleled by geographic patterns, with several areas reporting prevalence gaps (i.e., differences between the proportion of the population and the proportion of COVID-19 deaths) of >20%. (Figure 1) (1). This disparity is equally striking across some American cities. In Chicago, Black people represent 30% of the population but account for 45% of the deaths from COVID-19 (5). New York City (NYC), the epicenter of COVID-19 within the United States, has over 204,000 confirmed cases and over 21,000 deaths to date (6). In NYC, Black people make up 22% of the population but account for 28% of COVID-19 related deaths (6).

The high rates of infection and mortality are equally distressing among Latinx Americans, who represent 18% of the U.S. population but account for 34% of COVID-19 cases (1, 4). Similarly, in Florida, Latinx people make up 26% of the population but nearly 37% of COVID-19 cases (7). Furthermore, in San Francisco, 49% of COVID-19 cases are among Latinx people who make up only 15% of the population (8). The same social and structural circumstances that place Black and Latinx Americans at risk for disease exist across Native American communities; as the pandemic unfolds, infection rates for COVID-19 at the peak were highest in the Navajo Nation, as compared with any other place in the United States, including NYC (9). In states with falling cases and fewer cases overall of COVID-19, hot spots continue to disproportionately occur in communities of color (10).

As health-disparity researchers and educators and critical care and pulmonary providers on the front line caring for these patients, we believe it is imperative to report on the root causes that have led to these sobering statistics. Early in the pandemic, critical interventions to curb transmission—social distancing (11), early and widespread surveillance (12), and isolation of confirmed cases (13)—were slow to be implemented across the United States and were also disparately implemented and adopted across communities of color (14, 15). This has accentuated and compounded the root causes of disease disparities in the United States. The inequities in morbidity and mortality from the current COVID-19 pandemic offer a lens for long-standing racial or ethnic disparities in respiratory health (16, 17) in America. The recent deaths of George Floyd, Ahmaud Arbery, and Breonna Taylor, all lives shortened for being Black in the United States, highlight the important role of structural racism that has led to unequal prevalence of disease and death from COVID-19 across Black and Brown communities.

Structural, institutional, and individual discrimination against racial and ethnic minorities in the United States manifests through the shaping of neighborhoods, stagnant ability to generate wealth, targeted mass incarceration of minorities, and differential access to employment and resources. These racially based policies have been systematically detrimental to several minority groups in the United States (18), and their generational effects have resulted in unequal access to quality education and occupational opportunities, thus limiting socioeconomic growth. Such is the context for the present-day root causes and contributors to racial and ethnic health disparities in the United States, which are further accentuated by persistent racism and ongoing implicit bias in healthcare delivery. Notably, at the start of this pandemic, xenophobia and overtly racist labels for the disease had negative downstream effects, including personal attacks on Asian Americans, that likely slowed and misdirected the initial U.S. responses (19). Such responses echo past exclusionary and racist measures, including those after Pearl Harbor and September 11. It is neither possible nor appropriate to discuss racial or ethnic disparities in COVID-19 outcomes without acknowledging this long history of racial discrimination in the United States while also recognizing the resilience of communities of color.

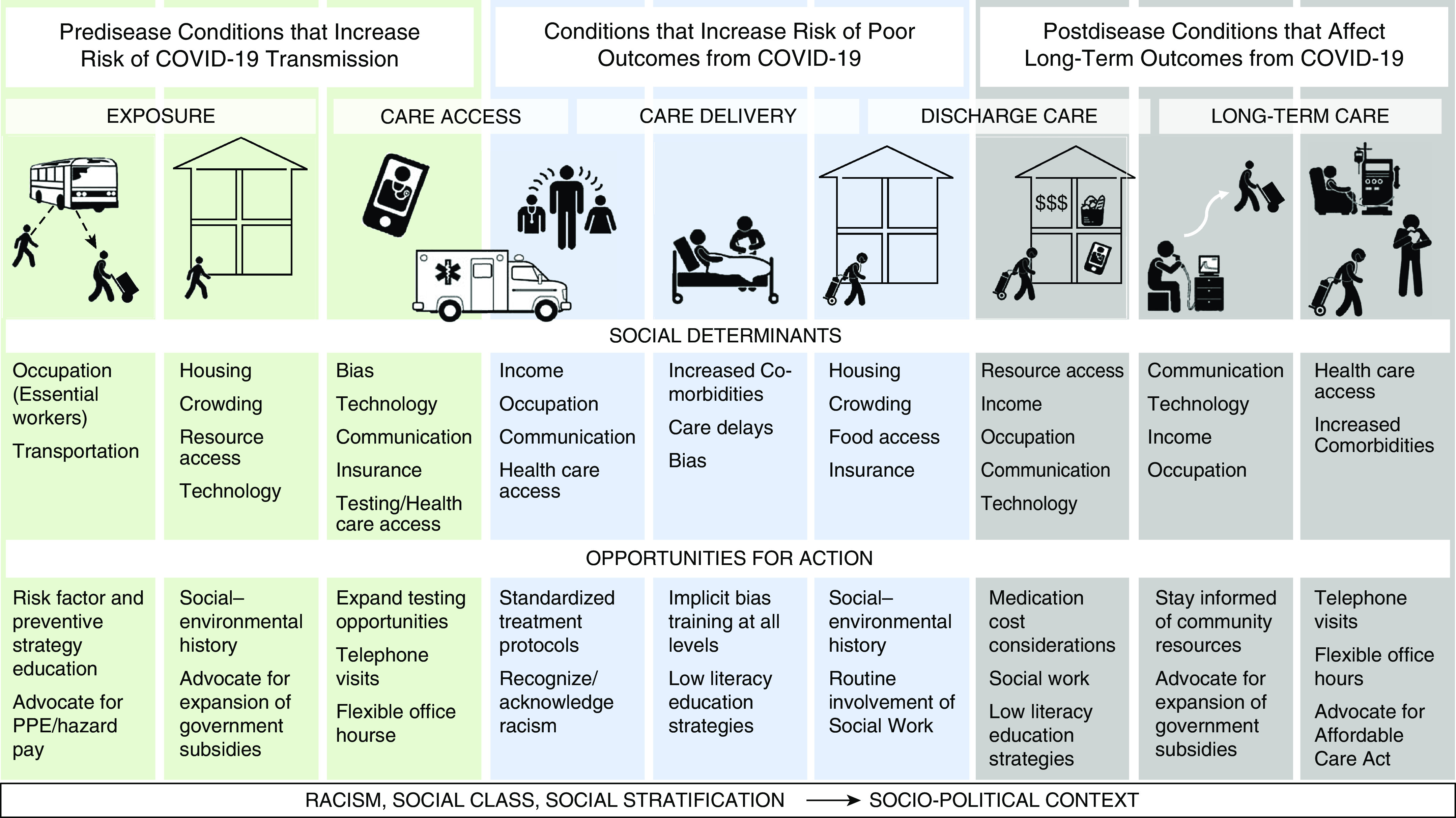

The social and structural determinants of health, that is, the circumstances in which people live and the systems and structures that shape experience and access, provide an avenue to systematically examine contributors to the marked disparities observed with COVID-19. Applying the World Health Organization Conceptual Framework for Action on Social Determinants of Health, we also identify potential avenues for policy action (Figure 2) (20). This framework differentiates how the socioeconomic and political contexts (e.g., government, policies, and cultures) manifest broadly as structural determinants (e.g., policies, socioeconomic status [SES], and racism), which shape exposure to intermediary social determinants (e.g., housing conditions, employment conditions, and psychosocial stress), including healthcare access, that ultimately create an individual’s unique social circumstances that shape behavior and risk for disease. This approach allows us to examine the immediate circumstances of living while also considering their broader context, allowing the identification of potential policies for change. For this Perspective, we focus on action steps that we, as members of the American Thoracic Society (ATS), should take to actively change the status quo and influence policies that address root causes.

Figure 2.

Structural and social determinants of health contributing to the racial and ethnic disparities in the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic in the United States and proposed areas for action, as informed by the World Health Organization Conceptual Framework for Action (26). PPE = personal protective equipment.

Specific to the COVID-19 pandemic, we describe the unique challenges that low-income communities, non–U.S.-born communities, and communities of color face. Such challenges increase the risk of disease and poor health outcomes and include 1) increased exposure due to occupational and/or living circumstances that make social distancing and self-isolation more difficult; 2) limited access to accurate, up-to-date information regarding the health risks of COVID-19; and 3) limited and differential access to healthcare services, including COVID-19 testing and care. These communities also have a higher burden of chronic diseases such as uncontrolled hypertension, obesity, diabetes mellitus, heart failure, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and have high rates of tobacco smoking (partly due to targeted marketing) (21), which places them at risk for having worse outcomes from COVID-19 (22). Moreover, the economic consequences from the pandemic and public health measures, specifically shelter-in-place orders, exacerbate these risk factors for disease and further transmission across vulnerable communities.

Increased Exposure

Historically disadvantaged communities have reduced capacity to adopt preventive measures. Cell phone mobilization data demonstrates that low-SES communities adopted social-distancing practices 3 days later than high-SES communities (14). In addition to fragmented delivery of public health messaging, high-density living settings limit the ability to practice social distancing. Shelters and other crowded living situations increase exposure risk and have become an ongoing concern for outbreaks across the country (including in San Francisco and Boston) (23). Relative to small (3%) national estimates, 16% of individuals living in the Navajo Nation live in crowded conditions, with multiple generations in one household because of high living costs and limited available housing (24, 25). In NYC, 70% of the workforce providing essential services (e.g., grocery store, delivery, and janitorial staff) are people of color (26); similar statistics are seen nationally (27). Fearful of job loss and dependent on hourly wage income, these workers continue to work despite limited access to protective equipment (28, 29). Furthermore, for essential workers, the need for child and elder care remains, increasing the social networks and exposure risk for some and increasing the economic burden for others. Fixed-income or limited-income households are also disadvantaged, as they are less able to “stock up” or afford food-delivery options, increasing the number of visits outside the home to obtain essential items (19). In individuals with confirmed COVID-19 who must quarantine, these factors become accentuated. These considerations have long-term implications, as the ability to self-isolate and rapidly readopt shelter-in-place orders will be crucial over the next 12–18 months, as we move from the acute phase of the pandemic to the second phase of disease containment.

Limited Access to Information

Despite greater risk for disease, minority communities with low SES and/or limited English proficiency receive less public communication during crises and pandemics (30, 31). Initially, COVID-19 messaging was overly complex, changing rapidly, and fraught with mixed messages, placing significant demand on vulnerable populations such as Latinx, Black, and Native American adults, whose health literacy is lower than that of non-Hispanic White adults (32). Early in pandemics, widespread outreach to improve understanding of viral transmission and knowledge of how to implement preventive measures is crucial to slowing transmission, yet vulnerable communities are less likely to receive these vital messages in easily interpretable language. Communication during natural disasters systematically disadvantages nonnative English speakers by using English-only messaging and limiting broadcasting to mainstream news outlets (30). Vulnerable populations have less internet access and are more likely to depend on community-targeted news sources, which limits their access to crucial information (33–35). During the 2009 H1N1 influenza pandemic, Savoia and colleagues (31) found home ownership to be associated with more than two and a half times the likelihood of H1N1 symptom knowledge.

Limited Access to Care

Testing Disparities

Curbing transmission is dependent on timely access to testing and care, which is greatly limited in low-SES and minority communities. During the pandemic, several community health centers and federally qualified health centers, the backbone for providing primary-care health services to the most vulnerable, have had to shutter their doors (36, 37). This has left many communities without access to timely testing and potentially without a lifeline for accessing care when feeling unwell. Furthermore, more resourced centers and communities are able to use third-party services to increase screening and testing capacity, whereas less-resourced areas are dependent on government-based resources, which have been slower to deploy and have test results taking up to 5 days to return (15). This is notable in San Francisco, where the University of California at San Francisco was able to develop a telehealth screening platform within 2 weeks of the start of the pandemic, reaching over 950 patients (38). Safety-net systems, the health systems that provide care to the most vulnerable populations, are often less resourced and lack sufficient funds to pivot as quickly. Moreover, such services are only truly available to patients who have reliable high-speed internet access, access to data and internet service plans and smart devices, and technology skills to create accounts and log on to platforms. As health systems transfer the majority of their care delivery to telemedicine, these gaps become more pronounced, further widening the care-access gap for testing of COVID-19 and chronic health conditions.

Care Disparities

Capital resources and surplus funds are commodities not often afforded to health systems and hospitals that strictly provide care to the urban poor, a group predominantly composed of Black and Latinx Americans and immigrant populations. Before the pandemic, debt and the proportion of uncompensated care was significantly higher in these safety-net hospitals than in more resourced centers that provide a greater proportion of their care to insured populations (39). These inequities across health systems have resulted in differential access to personal protective equipment for frontline workers (40), an inability to quickly access resources and convert space (i.e., building and equipping ICUs, installing negative-pressure units, and having dedicated COVID-19 units), and differential access to qualified personnel to prepare for surge and staff new units and beds. Such conditions likely increase risk of transmission to frontline workers (41, 42) and contribute to worse outcomes from COVID-19 (43).

What Is Our Role?

In 2013, the ATS made a commitment to health equity, diversity, and inclusion and continues to aim to reduce those disparities that are both avoidable and unjust. Change, extending from the individual’s role to the policy level, is imperative if the racial and ethnic disparities in disease burden and mortality associated with COVID-19 are to be reduced (20, 44). To move forward effectively, we outline important avenues through which the ATS and we, as ATS members, researchers, educators, and healthcare providers, can use our strengths for impact.

Check Our Biases and Promote Diverse Voices

The Black Lives Matter (45) movement and protests against racial injustice have led the nation to reflect on our own personal biases and our daily contribution to racism, overt and implicit. Over the past decade, there has been a movement in medical and academic programs to address racial and ethnic inequity through promoting and requiring implicit-bias training and implementing diversity, equity, and inclusion efforts. These efforts are a start, and we ask our members to learn about their own biases (https://implicit.harvard.edu) and reflect on their own experiences. However, as researchers, educators, and healthcare providers, we need to be more explicit in our actions to combat disparities. This includes applying an intentionality and holistic process to selecting pulmonary and critical care medicine fellows, not only to promote diverse voices but also to provide financial compensation to support these individuals and to purposely broaden our networks (“but I needed an expert” is not a valid excuse).

Since 2013, the ATS has formed the Health Equality and Diversity Committee, required diversity missions across all ATS committees, formed the Health Equality Fellowship to promote early-career investigators in this area, and made an explicit effort to ensure racial, ethnic, and gender diversity across all committees and leadership positions in the ATS. To further promote health-disparity research, more recently, the ATS and the American College of Chest Physicians (CHEST) have cosponsored the ATS/CHEST Foundation Research Grant in Diversity for junior investigators.

We need to hold ourselves accountable and do more. We push for appointing diversity champions across all committees and assemblies throughout the ATS to ensure that equity is considered and discussed at every level. The ATS should use the trust and scientific credibility that it has built to advocate for change on issues of systemic racism (in the same manner we have used to tackle tobacco and air pollution). The society should support traditionally underrepresented groups in science and in health-disparity research, through mentoring, strategic funding initiatives, ensuring diversity in selecting conference presenters and award recipients, and allocating investments to interventions and implementation science that will lead to change.

Increasing Accessibility of Information and Care

Communication regarding preventive measures, testing resources, public policy changes, and general guidance should be intentionally delivered by employing strategies for low health literacy and using multiple languages to reach people with low English proficiency. Working together, the ATS and CHEST organizations developed publicly available materials on COVID-19 in English and Spanish for those with low literacy (https://formylunghealth.com). However, as information regarding testing and care are highly regional, it is also important for our local chapters to actively work with local health systems and departments of public health to provide accessible information that is both accurate and clear.

In addition to developing educational materials, the ATS should consider working together with other medical societies to advocate for improved communication delivery by supporting efforts and legislation for universal access to broadband internet for all Americans (46). Closing this technological gap will allow underresourced people to access current and relevant information, including updates on changing policies both locally and nationally, as well as rapidly developing telehealth resources.

As healthcare providers caring for patients with COVID-19, we should consider the impact of limited literacy or language barriers when explaining strategies to mitigate COVID-19 exposures. Using strategies for low health literacy, such as using plain language and accessible teach-back approaches, education should be provided on risk factors and prevention strategies, how to access testing and care for COVID-19, and the potential future role of vaccines in vulnerable populations. Be cognizant and ask about potential barriers to accessing and using technology, including lack of electronic devices, limited data storage on devices, limited internet access, and costs of data plans. Consider use of low-tech solutions, such as telephone visits, to ensure remote access to health care, and query patients about their preferences.

Fund, Report, and Reflect on Root Causes of Health Inequity (ATS)

Reducing disparities from COVID-19 requires awareness and understanding of the scope of the disparities themselves and the underlying social and structural determinants that have contributed and are primed for intervention. The CDC now mandates reporting on race and ethnicity for all COVID-19 cases (1), but we need to go further and support research that examines and addresses root causes. In response to the COVID-19 pandemic, the ATS has received over $1 million (an amount that continues to grow) in philanthropic donations. From this, the ATS is dedicating a significant portion to support junior investigators researching COVID-19 inequities and mechanisms to decrease the disparity gap, as well as to developing resources for low health literacy that target communities that have been most severely affected by the outbreak.

As healthcare providers, ask about relevant COVID-19 exposures (e.g., work-, transportation-, or housing-related) when evaluating patients from vulnerable populations with upper respiratory symptoms. Assess structural barriers to care for minority and low-SES patients with COVID-19, including insurance, copayments, transportation, childcare, food insecurity, lack of housing, etc., and evaluate how these can negatively affect the patient’s care plan. Refer patients in need to social workers, local programs, and/or community resources. Address potential postdischarge challenges faced by minority and low-SES patients hospitalized for COVID-19, including job loss/limited job, lack of insurance coverage, housing problems, and care for comorbidities.

Set Standards and Practice Guidelines

Specifically regarding protections for essential workers, an especially high-risk group, we are in dire need of standardization in safety recommendations and broad access to personal protective equipment across all employment types (47). As the ATS, we are in a position to continue to provide recommendations on these regulations to governing agencies and to advocate for funding support for personal protective equipment for high-risk jobs, including nonmedical essential workers, who regularly interact with the public. Furthermore, asz hazard payments are actively discussed for frontline medical workers, it is equally important to advocate for and support measures that provide hazard pay for all essential workers in medical settings, such as medical assistants and nutritional and environmental service workers (48).

As we continue to develop resources and recommendations on how to care for patients with COVID-19 (https://www.thoracic.org/covid/index.php), we need to ensure that such guidelines are designed to support equitable health outcomes across all population groups. This includes providing guidelines on how to operate in low-resource settings, such as safety-net settings, and how to ethically redeploy and train non-ICU healthcare providers to provide high-quality care in surge-capacity situations.

Take a Position

Increasing access to high-quality COVID-19 care, including testing, is necessary (15). The Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security Act provided some of the necessary infrastructure support for community health centers and federally qualified health centers (49). In addition to this, expansion of the Affordable Care Act (ACA) to provide free COVID-19 care, including emergency department visits or hospitalizations, and access to comprehensive telehealth services would improve COVID-19 outcomes, which are significantly worse for individuals with comorbid disease, who are disproportionately represented in historically disadvantaged communities. The ATS believes health care is a right (50). The ATS believes that universal access to affordable health insurance is a necessary, but insufficient, step to close the gap on health disparities in the United States, and this is the primary reason the ATS has been in continuous support of the ACA. As the ACA is repeatedly challenged in the court system, the ATS has filed multiple amicus briefs in support of the constitutionality and effectiveness of the ACA. Because the pandemic has clearly demonstrated that social conditions shape outcomes, we should consider working with peer societies throughout the medical and scientific community to support policy efforts that attempt to address these important social and structural determinants of health.

Conclusions

As stated by Franklin D. Roosevelt, “it isn’t sufficient just to want—you’ve got to ask yourself what you are going to do to get the things you want.”

Critical care and pulmonary specialists play a major role in facing and overcoming the COVID-19 pandemic, an event of truly historic proportions. As such, we are in a unique position to advocate for underrepresented minority patients, who are becoming critically ill and dying at disproportionate rates. In so doing, we should take active measures in our own delivery of health care and support actions and policies that improve access to information and care, while reducing exposure risk in vulnerable populations. Targeted policy interventions that protect high-risk racial and ethnic minority groups should reduce both ongoing health disparities in COVID-19 and long-standing disparities in respiratory health (16, 17).

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Supported by grant K23HL12551 (N.T.) from the NIH and from the Nina Ireland Program for Lung Health; grant 5K01HL140216 (S.L.-D.) from the NIH and from the Harold Amos Medical Faculty Development award through the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation; grant K08 HL141623 (C.B.) from the NIH; grants R01HL126508, R01HL129198, R01131418, R01HL142749, and R34HL143747 (J.P.W.) from the NHLBI; grants R01CA203193, R01CA202956, and T32CA225617 (J.P.W.) from the National Cancer Institute; grants U01OH011312 and U01OH11479 (J.P.W.) from the National Institute of Occupational Safety and Health; grant R01AG066471 (J.P.W.) from the National Institute on Aging; grant UM1AI114271 (J.P.W.) from National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases; and grants HL117191, HL119952, and MD011764 (J.C.C.) from the NIH. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

Author Contributions: N.T. conceptualized the idea, and N.T. and S.L.-D. drafted the first version of the manuscript. All authors provided input, revisions, and approval of the final version to be published.

Originally Published in Press as DOI: 10.1164/rccm.202005-1523PP on July 17, 2020

Author disclosures are available with the text of this article at www.atsjournals.org.

Contributor Information

Collaborators: on behalf of the Health Equality and Diversity Committee of the American Thoracic Society

References

- 1.CDC. Atlanta, GA: CDC; 2019. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): cases in the U.S. [accessed 2020 Apr 26]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/cases-updates/cases-in-us.html. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Seervai S. New York, NY: The Commonwealth Fund; 2019. It’s harder for people living in poverty to get health care. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Golden L. Washington, DC: Economic Policy Institute; 2014. Flexibility and overtime among hourly and salaried workers: when you have little flexibility, you have little to lose. [accessed 2020 Apr 26]. Available from: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2597174. [Google Scholar]

- 4.U.S. Census Bureau. Suitland, Suitland-Silver Hill, MD: U.S. Census Bureau; 2019. QuickFacts: United States. [accessed 2020 Apr 26]. Available from: https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/US/PST045219#PST045219. [Google Scholar]

- 5.City of Chicago. Chicago, IL: City of Chicago Government; 2020. Latest data. [accessed 2020 Apr 29]. Available from: https://www.chicago.gov/city/en/sites/covid-19/home/latest-data.html. [Google Scholar]

- 6.New York State Department of Health. Albany, NY: New York State Department of Health; 2020. Workbook: NYS COVID-19 tracker. [accessed 2020 Apr 26]. Available from: https://covid19tracker.health.ny.gov/views/NYS-COVID19-Tracker/NYSDOHCOVID-19Tracker-Fatalities?%3Aembed=yes&%3Atoolbar=no&%3Atabs=n. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Florida Department of Health. Tallahassee, FL: Florida Department of Health; 2020. What you need to know now about COVID-19 in Florida. [accessed 2020 Apr 26]. Available from: https://floridahealthcovid19.gov/#latest-stats. [Google Scholar]

- 8.City and County of San Francisco. San Francisco, CA: City and County of San Francisco; 2020. DataSF: COVID-19 data and reports. [accessed 2020 Apr 20]. Available from: https://data.sfgov.org/stories/s/San-Francisco-COVID-19-Data-Tracker/fjki-2fab/ [Google Scholar]

- 9.Navajo Department of Health. Window Rock, AZ: Navajo Department of Health; 2020. COVID-19. [accessed 2020 Apr 27]. Available from: https://www.ndoh.navajo-nsn.gov/COVID-19. [Google Scholar]

- 10.CDC. Atlanta, GA: CDC; 2020. Weekly updates by select demographic and geographic characteristics: provisional death counts for coronavirus disease (COVID-19) [accessed 2020 Apr 20]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nvss/vsrr/covid_weekly/ [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ferguson NM, Laydon D, Nedjati-Gilani G, Imai N, Ainslie K, Baguelin M, et al. Imperial College COVID-19 Response Team. London, UK: Imperial College London; 2020. Impact of non-pharmaceutical interventions (NPIs) to reduce COVID-19 mortality and healthcare demand. DOI: 10.25561/77482. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sullivan P. Washington, DC: The Hill; 2020. Slow testing rollout sets back US coronavirus response. [accessed 2020 Apr 27]. Available from: https://thehill.com/policy/healthcare/public-global-health/487521-slow-testing-rollout-sets-back-us-coronavirus-response. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Niu Y, Xu F. Deciphering the power of isolation in controlling COVID-19 outbreaks. Lancet Glob Health. 2020;8:e452–e453. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(20)30085-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Valentino-DeVries J, Lu D, Dance GJX. New York, NY: New York Times; 2020. Location data says it all: staying at home during coronavirus is a luxury. [accessed 2020 Apr 21]. Available from: https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2020/04/03/us/coronavirus-stay-home-rich-poor.html. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Farmer B. San Francisco, CA: Kaiser Health News; 2020. Long-standing racial and income disparities seen creeping into COVID-19 care. [accessed 2020 Apr 29]. Available from: https://khn.org/news/covid-19-treatment-racial-income-health-disparities/ [Google Scholar]

- 16.Celedón JC, Roman J, Schraufnagel DE, Thomas A, Samet J. Respiratory health equality in the United States: the American thoracic society perspective. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2014;11:473–479. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201402-059PS. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Celedón JC, Burchard EG, Schraufnagel D, Castillo-Salgado C, Schenker M, Balmes J, et al. American Thoracic Society and the NHLBI. An American Thoracic Society/National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute workshop report: addressing respiratory health equality in the United States. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2017;14:814–826. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201702-167WS. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bailey ZD, Krieger N, Agénor M, Graves J, Linos N, Bassett MT. Structural racism and health inequities in the USA: evidence and interventions. Lancet. 2017;389:1453–1463. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30569-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Braithwaite R, Warren R. The African American petri dish [preprint] J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2020 doi: 10.1353/hpu.2020.0037. [accessed 2020 Apr 20] Available from: https://preprint.press.jhu.edu/jhcpu/preprints/african-american-petri-dish. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Solar O, Irwin A. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2010. A conceptual framework for action on the social determinants of health: social determinants of health discussion paper 2. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Moore DJ, Williams JD, Qualls WJ. Target marketing of tobacco and alcohol-related products to ethnic minority groups in the United States. Ethn Dis. 1996;6:83–98. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cockerham WC, Hamby BW, Oates GR. The social determinants of chronic disease. Am J Prev Med. 2017;52:S5–S12. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2016.09.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Holder S, Capps K. New York, NY: Bloomberg L.P.; 2020. No easy fixes as COVID-19 hits homeless shelters. [accessed 2020 Apr 29]. Available from: https://www.citylab.com/equity/2020/04/homeless-shelter-coronavirus-testing-hotel-rooms-healthcare/610000/ [Google Scholar]

- 24.U.S. Census Bureau. Suitland, Suitland-Silver Hill, MD: U.S. Census Bureau; 2020. 2018: ACS survey 5-year estimates, Table B25014C [customized by Thakur N] [accessed 2020 Apr 26]. Available from: https://data.census.gov/cedsci/table?q=United States&tid=ACSDT5Y2018.B25014C&t=Occupants Per Room&vintage=2018. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pindus N, Kingsley TG, Biess J, Levy D, Simington J, Hayes C. Washington, DC: Office of Policy Development and Research, U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development; 2017. Housing needs of American Indians and Alaska natives in tribal areas: a report from the assessment of American Indian, Alaska Native, and Native Hawaiian housing needs. executive summary. [accessed 2020 Apr 26]. Available from: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3055776. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Office of the New York City Comptroller. New York, NY: Office of the New York City Comptroller; 2020. New York City’s Frontline Workers : Office of the New York City Comptroller Scott M. Stringer. [accessed 2020 Apr 21]. Available from: https://comptroller.nyc.gov/reports/new-york-citys-frontline-workers/ [Google Scholar]

- 27.U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. Washington, DC: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics; 2020. Employed persons by detailed occupation, sex, race, and Hispanic or Latino ethnicity. [accessed 2020 Apr 29]. Available from: https://www.bls.gov/cps/cpsaat11.htm. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sanchez M. New York, NY: ProPublica; 2020. “Essential” factory workers are afraid to go to work and cannot afford to stay home. [accessed 2020 Apr 21] Available from: https://www.propublica.org/article/coronavirus-essential-factory-workers-illinois. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Grabell M, Bernice Y, Jameel M. New York, NY: ProPublica; 2020. Millions of essential workers are being left out of COVID-19 workplace safety protections. [accessed 2020 Apr 21]. Available from: https://www.propublica.org/article/millions-of-essential-workers-are-being-left-out-of-covid-19-workplace-safety-protections-thanks-to-osha. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ahlborn L, Franc JM. Tornado hazard communication disparities among Spanish-speaking individuals in an English-speaking community. Prehosp Disaster Med. 2012;27:98–102. doi: 10.1017/S1049023X12000015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Savoia E, Testa MA, Viswanath K. Predictors of knowledge of H1N1 infection and transmission in the U.S. population. BMC Public Health. 2012;12:328. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-12-328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kutner M, Greenberg E, Jin Y, Paulsen C. The health literacy of America’s adults: results from the 2003 National Assessment of Adult Literacy. Education. 2006;6:1–59. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Anderson M, Kumar M. Washington, DC: Pew Research Center; 2019. Lower-income Americans still lag in tech adoption. [accessed 2020 Apr 21]. Available from: https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2019/05/07/digital-divide-persists-even-as-lower-income-americans-make-gains-in-tech-adoption/ [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pew Research Center. Washington, DC: Pew Research Center; 2019. Hispanic black news media fact sheet. [accessed 2020 Apr 21]. Available from: https://www.journalism.org/fact-sheet/hispanic-and-black-news-media/ [Google Scholar]

- 35.Waldman S, Sennott C. Washington, DC: The Atlantic; 2020. The coronavirus is killing local news. [accessed 2020 Apr 21]. Available from: https://www.theatlantic.com/ideas/archive/2020/03/coronavirus-killing-local-news/608695/ [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shin P, Morris R, Velasquez M, Rosenbaum S, Somodevilla A. Washington, DC: Health Affairs; 2020. Keeping community health centers strong during the coronavirus pandemic is essential to public health. [accessed 2020 Apr 21]. Available from: https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/hblog20200409.175784/full/ [Google Scholar]

- 37.Katoni M, Sparling N. New York, NY: New York Times; 2020. Coronavirus in California: community health centers face challenges. [accessed 2020 Apr 21]. Available from: https://www.nytimes.com/2020/04/13/us/coronavirus-california-health-care-clinics.html. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Judson TJ, Odisho AY, Neinstein AB, Chao J, Williams A, Miller C, et al. Rapid design and implementation of an integrated patient self-triage and self-scheduling tool for COVID-19. J Am Med Inf Assoc. 2020;27:860–866. doi: 10.1093/jamia/ocaa051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Popescu I, Fingar KR, Cutler E, Guo J, Jiang HJ. Comparison of 3 safety-net hospital definitions and association with hospital characteristics. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2:e198577. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.8577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Stremikis K. Oakland, CA: California Health Care Foundation; 2020. COVID-19 tracking poll: more critical care doctors report sufficient protective gear and tests. [accessed 2020 Jun 5]. Available from: https://www.chcf.org/blog/covid-19-tracking-poll-more-doctors-report-sufficient-protective-gear-tests/ [Google Scholar]

- 41.Heinzerling A, Stuckey MJ, Scheuer T, Xu K, Perkins KM, Resseger H, et al. Transmission of COVID-19 to health care personnel during exposures to a hospitalized patient: Solano County, California, February 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69:472–476. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6915e5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chou R, Dana T, Buckley DI, Selph S, Fu R, Totten AM. Epidemiology of and risk factors for coronavirus infection in health care workers. Ann Intern Med. 2020;173:120–136. doi: 10.7326/M20-1632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Eriksson CO, Stoner RC, Eden KB, Newgard CD, Guise JM. The association between hospital capacity strain and inpatient outcomes in highly developed countries: a systematic review. J Gen Intern Med. 2017;32:686–696. doi: 10.1007/s11606-016-3936-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Benfer EA, Wiley LF. Washington, DC: Health Affairs; 2020. Health justice strategies to combat COVID-19: protecting vulnerable communities during a pandemic. [accessed 2020 Apr 29]. Available from: https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/hblog20200319.757883/full/ [Google Scholar]

- 45.Home: black lives matter. Black Lives Matter Global Network [accessed 2020 Jun 12]. Available from: https://blacklivesmatter.com/

- 46.Reglitz M. The human right to free internet access. J Appl Philos. 2020;37:314–331. [Google Scholar]

- 47.U.S. Department of Labor Occupational Safety and Health Administration. Guidance on preparing workplaces for COVID-19. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Labor;; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kinder M. Washington DC: Brookings Institution; 2020. COVID-19’s essential workers deserve hazard pay: here’s why—and how it should work. [accessed 2020 May 1] Available from: https://www.brookings.edu/research/covid-19s-essential-workers-deserve-hazard-pay-heres-why-and-how-it-should-work/ [Google Scholar]

- 49.McConnell M. S. 3548, 116th Congress (2019–2020): CARES Act.; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 50.U.S. House of Representatives Ways and Means Committee, Subcommittee on Health. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Publishing Office; 1993. Health care reform : hearings before the Subcommittee on Health of the Committee on Ways and Means, House of Representatives, One Hundred Third Congress, First Session. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.