To the Editor:

Some patients with coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pneumonia demonstrate severe hypoxemia despite having near normal lung compliance, a combination not commonly seen in typical acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) (1). The disconnect between gas exchange and lung mechanics in COVID-19 pneumonia has raised the question of whether the mechanisms of hypoxemia in COVID-19 pneumonia differ from those in classical ARDS. Dual-energy computed tomographic imaging has demonstrated pulmonary vessel dilatation (2) and autopsies have shown pulmonary capillary deformation (3) in patients with COVID-19 pneumonia.

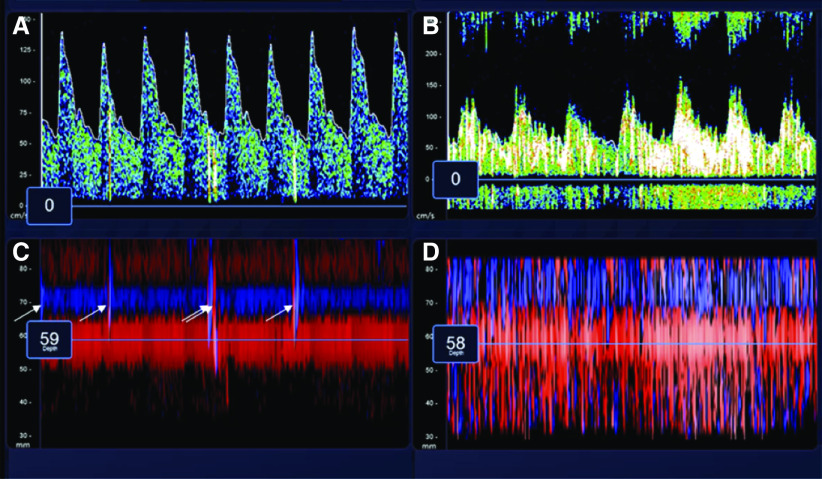

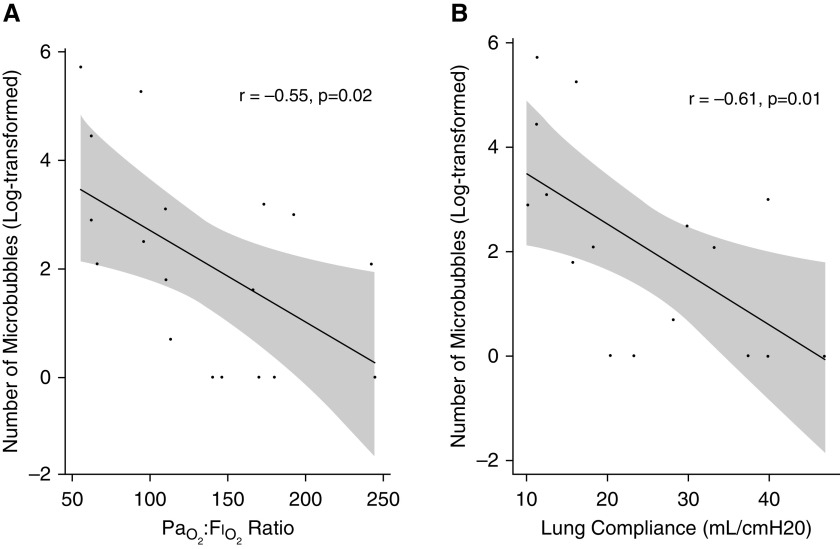

Contrast-enhanced transcranial Doppler (TCD) of the bilateral middle cerebral arteries after the injection of agitated saline is an ultrasound technique, similar to transthoracic or transesophageal echocardiography, that can be performed to detect microbubbles and diagnose intracardiac or intrapulmonary shunt (Figure 1) (4, 5). TCD is more sensitive than transthoracic echocardiography in detecting right-to-left shunt, (6) and it is less invasive than transesophageal echocardiography. We performed a cross-sectional pilot study of TCD (Lucid Robotic System; NovaSignal Corp) in all mechanically ventilated patients with severe COVID-19 pneumonia from two COVID-19 ICUs who were not undergoing continuous renal replacement therapy or extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (N = 18). This study was approved by the Mount Sinai Institutional Review Board (approval 20–03660). Agitated saline was injected through either a peripheral intravenous line in the upper extremity or a central line in the internal jugular vein. The system software automatically counted the number of microbubbles detected over 20 seconds; as a quality control measure, we manually counted and confirmed the number of microbubbles and were blinded to the patients’ clinical condition and PaO2:FiO2 ratio. Sixty-one percent (n = 11) of patients were men. Patients had a median age of 59 years (interquartile range, 54–68 years), with a PaO2:FiO2 ratio of 127 mm Hg (interquartile range, 94–173 mm Hg). Lung compliance was measured in 16 patients and was low (median 22 ml/cm H2O; interquartile range 15–34 ml/cm H2O). None of the patients had a known history of chronic liver disease or preexisting intracardiac shunt. Contrast-enhanced TCD detected a median of 8 microbubbles (interquartile range, 1–22; range 0–300). Three major findings from contrast-enhanced TCD were observed. First, 15 of 18 (83%) patients had detectable microbubbles (see Figure 1 for representative images). Second, the PaO2:FiO2 ratio was inversely correlated with the number of microbubbles (Pearson’s r = −0.55; P = 0.02) (Figure 2A). Third, the number of microbubbles was inversely correlated to lung compliance (Pearson’s r = −0.61; P = 0.01) (Figure 2B).

Figure 1.

Assessment of microbubbles by transcranial Doppler (TCD) after injection of agitated saline. Representative images were captured during TCD evaluation after injection of agitated saline. (A and B) Continuous spectral waveforms of the middle cerebral artery (MCA) during insonation over 5 seconds. C and D demonstrate the power M-mode, and positive microbubbles appear as vertical lines (arrows). (A and C) Images from the left MCA of a 60-year-old woman in whom TCD detected five microbubbles. (B and D) Images from the right MCA of a 69-year-old man in whom TCD detected 300 microbubbles. His PaO2:FiO2 ratio was 55 mm Hg, which was the lowest in the cohort.

Figure 2.

Associations between number of microbubbles and PaO2:FiO2 ratio and lung compliance. (A) A scatterplot of the log-transformed number of microbubbles as detected by transcranial Doppler and PaO2:FiO2 ratio (r = −0.55; P = 0.02) and suggests that the number of microbubbles increases with declining PaO2:FiO2 ratio. (B) A scatterplot of the log-transformed number of microbubbles as detected by transcranial Doppler and lung compliance (r = −0.61; P = 0.01) and suggests that the number of microbubbles increases with declining lung compliance.

These data suggest that pulmonary vasodilatations may explain the disproportionate hypoxemia in some patients with COVID-19 pneumonia and, somewhat surprisingly, track with poor lung compliance (1). Our detection of transpulmonary bubbles may be analogous to hepatopulmonary syndrome, a pulmonary vascular disorder of chronic liver disease characterized by pulmonary vascular dilatations with increased blood flow to affected lung units, which results in ventilation–perfusion mismatch and hypoxemia (4). The normal lung filters microbubbles from the injection of agitated saline as the bubble diameter is larger (smallest bubble approximately 24 μm in diameter [5]) than the normal pulmonary capillary (<15 μm in diameter [7]). In hepatopulmonary syndrome, and similar to what we observed in this pilot study, the presence and degree of transpulmonary bubble transit correlate with the degree of hypoxemia (8). Although we cannot rule out intracardiac shunt as a cause of observed microbubbles, we note that the prevalence of transpulmonary bubbles seen in our study is markedly higher than the prevalence of patent foramen ovales seen in the general population (9). In a prior study of 265 patients with ARDS receiving mechanical ventilation, only 42 patients (16%) were found to have patent foramen ovale as assessed by contrast transesophageal echocardiography (10).

Hypoxemia in ARDS is predominantly caused by right-to-left shunt, in which systemic venous blood flows to lung regions with collapsed and/or flooded alveoli and does not get oxygenated as it passes through the lung (11). Transpulmonary bubble transit has been detected in 26% of patients with classical ARDS, although neither their presence nor their severity correlates with oxygenation (10), implying that pulmonary vascular dilatations are not a major mechanism of hypoxemia in typical ARDS. In order for transpulmonary bubble transit to occur, pulmonary vascular dilatations or pulmonary arteriovenous malformations must be present; a lack of hypoxic vasoconstriction is not sufficient. Although these observations are preliminary, the correlation seen here between the degree of transpulmonary bubble transit and PaO2:FiO2 ratio suggests that pulmonary vascular dilatation may be a significant cause of hypoxemia in patients with COVID-19 respiratory failure. Interestingly, patients with worse lung compliance demonstrated more microbubbles, which suggests that pulmonary vascular dilatation may worsen in parallel with the typical diffuse alveolar damage of ARDS.

Our understanding of the pathophysiology of hypoxemic respiratory in COVID-19 is limited. Although a larger, confirmatory study is needed, these data, in conjunction with recent radiographic and autopsy findings, seem to implicate pulmonary vascular dilatation as a cause of hypoxemia in patients with COVID-19 pneumonia.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Supported by NIH grants R01 HL141268 (C.E.V.) and K23 HL135349 and R01 MD013310 (A.G.L.).

Author Contributions: A.S.R.: concept, data gathering, interpretation, and drafting of the manuscript. A.G.L.: data analysis, interpretation, and drafting of the manuscript. J.R.: data gathering, interpretation, and revision of the manuscript. K.D.: data gathering, interpretation, and revision of the manuscript. J.L.: concept and revision of the manuscript. C.A.P.: interpretation and revision of the manuscript. C.E.V.: interpretation, data analysis, and revision of the manuscript. H.D.P.: concept, data gathering, interpretation, and drafting of the manuscript.

Originally Published in Press as DOI: 10.1164/rccm.202006-2219LE on August 6, 2020

Author disclosures are available with the text of this letter at www.atsjournals.org.

References

- 1.Gattinoni L, Coppola S, Cressoni M, Busana M, Rossi S, Chiumello D. Covid-19 does not lead to a “typical” acute respiratory distress syndrome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2020;201:1299–1300. doi: 10.1164/rccm.202003-0817LE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lang M, Som A, Mendoza DP, Flores EJ, Reid N, Carey D, et al. Hypoxaemia related to COVID-19: vascular and perfusion abnormalities on dual-energy CT Lancet Infect Dis[online ahead of print] 30 Apr 2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ackermann M, Verleden SE, Kuehnel M, Haverich A, Welte T, Laenger F, et al. Pulmonary vascular endothelialitis, thrombosis, and angiogenesis in Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:120–128. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2015432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ramírez Moreno JM, Millán Núñez MV, Rodríguez Carrasco M, Ceberino D, Romaskevych-Kryvulya O, Constantino Silva AB, et al. Detection of an intrapulmonary shunt in patients with liver cirrhosis through contrast-enhanced transcranial Doppler: a study of prevalence, pattern characterization, and diagnostic validity [in Spanish] Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;38:475–483. doi: 10.1016/j.gastrohep.2015.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Teague SM, Sharma MK. Detection of paradoxical cerebral echo contrast embolization by transcranial Doppler ultrasound. Stroke. 1991;22:740–745. doi: 10.1161/01.str.22.6.740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Katsanos AH, Psaltopoulou T, Sergentanis TN, Frogoudaki A, Vrettou AR, Ikonomidis I, et al. Transcranial Doppler versus transthoracic echocardiography for the detection of patent foramen ovale in patients with cryptogenic cerebral ischemia: a systematic review and diagnostic test accuracy meta-analysis. Ann Neurol. 2016;79:625–635. doi: 10.1002/ana.24609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Townsley MI. Structure and composition of pulmonary arteries, capillaries, and veins. Compr Physiol. 2012;2:675–709. doi: 10.1002/cphy.c100081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fischer CH, Campos O, Fernandes WB, Kondo M, Souza FL, De Andrade JL, et al. Role of contrast-enhanced transesophageal echocardiography for detection of and scoring intrapulmonary vascular dilatation. Echocardiography. 2010;27:1233–1237. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8175.2010.01228.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hagen PT, Scholz DG, Edwards WD. Incidence and size of patent foramen ovale during the first 10 decades of life: an autopsy study of 965 normal hearts. Mayo Clin Proc. 1984;59:17–20. doi: 10.1016/s0025-6196(12)60336-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Boissier F, Razazi K, Thille AW, Roche-Campo F, Leon R, Vivier E, et al. Echocardiographic detection of transpulmonary bubble transit during acute respiratory distress syndrome. Ann Intensive Care. 2015;5:5. doi: 10.1186/s13613-015-0046-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dantzker DR, Brook CJ, Dehart P, Lynch JP, Weg JG. Ventilation-perfusion distributions in the adult respiratory distress syndrome. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1979;120:1039–1052. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1979.120.5.1039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.