Abstract

Objective

To assess the efficacy of the Support, Educate, Empower (SEE) glaucoma coaching program on medication adherence among glaucoma patients with low adherence.

Design

Uncontrolled intervention study with a pre-post design.

Participants

Glaucoma patients ≥ age 40, taking ≥1 medication, who self-reported poor adherence were recruited from the University of Michigan Kellogg Eye Center. Adherence was monitored electronically for a 3-month baseline period; participants with median adherence ≤80% were enrolled in the SEE Program.

Methods

Participants’ adherence was monitored electronically (AdhereTech, New York, NY) during the 7-month program. Adherence was calculated as the percentage of doses taken on time out of those prescribed. The SEE Program included 1) automated medication reminders; 2) 3 in-person counseling sessions with a glaucoma coach who had training in motivational interviewing (MI); and 3) 5 phone calls with the same coach for between-session support. The coach used a web-based tool to generate an education plan tailored to the patient’s glaucoma diagnosis, test results, and ophthalmologist’s recommendations (www.glaucomaeyeguide.org). The tool guided an Ml-based conversation between coach and patient to identify barriers to adherence and possible solutions. Descriptive statistics were used to summarize baseline patient characteristics, and differences between those who did and did not complete the SEE Program were tested with 2-sample t-, chi-square, and Fisher exact tests. Adherence was compared before and after the SEE Program with paired t-tests.

Main Outcome Measure

Change in electronically monitored medication adherence.

Results

A total of 48 participants were enrolled. The participants were 54% male, 46% white, on average 64 years old (standard deviation, SD=10.8), with an average worse eye mean deviation (MD) of −7.9 dB (SD=8.8). Those completing the SEE Program (n=39) did not differ significantly from those who dropped out (n=9) on sex, race, age, MD, or baseline adherence. Medication adherence improved from 59.9% at baseline to 81.3% (p<0.0001) after completing the SEE Program. 95% of participants showed an improvement in adherence (mean relative improvement=21.4%, SD=16.5%, range=−3.2% to 74.4%, median=20.1%). 59.0% of participants had adherence >80% upon completing the SEE Program.

Conclusions

SEE Program participants had a clinically meaningful, statistically significant improvement in glaucoma medication adherence.

Despite the availability of effective treatments, glaucoma causes more people to become irreversibly blind than any other disease worldwide, especially among socially and economically disadvantaged groups.1,2 One major contributor is that roughly 80% of adults with glaucoma do not take their medications as prescribed.3–5 African Americans and people with lower socioeconomic status are more likely to experience poor medication adherence and resulting adverse vision outcomes.5–7 Poor medication adherence is related to greater vision loss from glaucoma.8–10 There are many reasons for poor adherence, including inadequate skills, (e.g., difficulty with eye drop instillation), medication cost, psycho-social issues (e.g., skepticism that an asymptomatic disease will lead to blindness, lack of trust in health care providers), and others.6,11–14 Under current practice guidelines, physicians are expected to provide participant counseling but are hard pressed for adequate time, limiting the ability to adequately address medication adherence.8

A recent Cochrane Review of medication adherence interventions found that, overall, interventions were not successful.15 However, programs that were successful across a wide variety of chronic diseases were those that included: 1) evidence-based and theory-based interventions; 2) tailored education; 3) motivational interviewing (Ml)-based counseling; and 4) reminder systems.16 Software to tailor education generates unique informational and support messages based on a participant’s survey responses, medical record data (e.g. visual field indices), and socio-demographic characteristics.17 Ml engages participants by discussing personal priorities and obstacles and builds autonomous motivation by linking change to personal value and meaning.18 As an example of the efficacy of Ml, when health care workers trained in Ml-delivered tailored education and counseling to participants with diabetes, participants improved their glycemic control at a level similar to what would have been attained by adding an additional oral medication to the treatment regimen.19 Building on this success in other chronic conditions, we developed a training program for ophthalmic technicians and health educators to learn glaucoma-specific MI counseling approaches. In our pilot study of this training program, participant satisfaction with staff communication significantly increased among staff with better MI skills compared to those with worse MI skills.19

The Support, Educate, Empower (SEE) Program combines 1) successful evidence- based behavior change approaches; 2) an eHealth tool to deliver personalized education (e.g. based on each person’s diagnosis, test results, physician’s recommendations); 3) a coach trained in glaucoma-specific MI-based counseling to guide glaucoma participants to identify and overcome their barriers to optimal adherence; and 4) an alert and reminder system tailored to the participant’s medication schedule. The SEE Program, in particular the MI component, is grounded in Self Determination Theory, a theory of human growth and behavior change that posits that a person will change their behavior when they feel volitional, competent, and autonomously motivated to change.16 The objective of this prospective pre-post uncontrolled pilot intervention study (Clinical-Trials.gov Identifier #NCT03159247) was to evaluate the feasibility and efficacy of the SEE Program among glaucoma patients with poor medication adherence.

Methods

Participants and Sample Selection

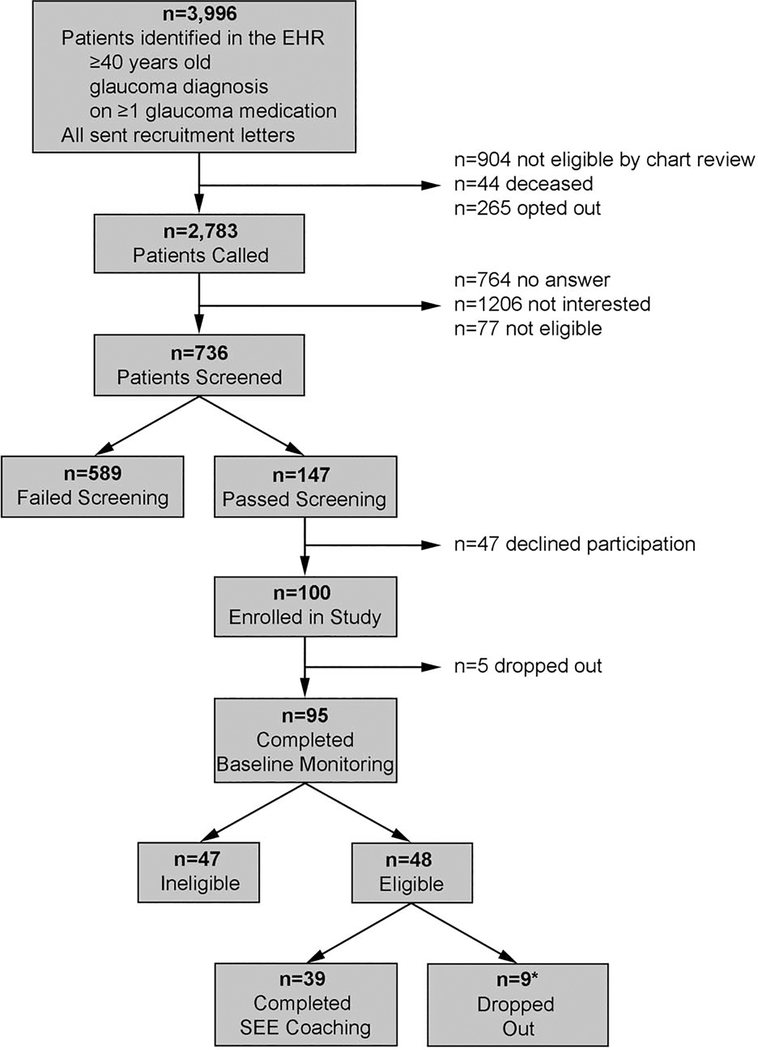

Participants were recruited between December 2016 and August 2018. We used an automated data pull to identify patients who received ophthalmic care at any of the 11 eye clinics in the University of Michigan Health System, had a diagnosis of glaucoma, glaucoma suspect or ocular hypertension, were ≥40 years old, and took ≥1 glaucoma medication. Potential participants were mailed letters to notify them about a study involving a personalized glaucoma coaching program and gave instructions for how to opt-out of receiving a recruitment phone call. A manual chart review was performed to exclude individuals who were deceased, those with severe mental illness (defined as schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, or a major depressive episode with psychotic features), or cognitive impairment. A research associate called each patient who did not opt-out or have exclusion criteria to ask if they would be interested in participating. If the patient was interested, the research associate obtained verbal consent to ask screening questions. To pass screening for the study, participants had to speak English, instill their own eye drops, and self-report poor adherence on 2 validated scales, the Chang Adherence measure20 and the Morisky Medication Adherence Scale.21,22 Those who self-reported <95% adherence over the past month on the Chang measure and scored ≤6 on the Morisky scale were considered to have poor adherence by self-report. See Figure 1 for the CONSORT diagram of participant recruitment, screening, and enrollment.

Figure 1.

Flow Chart of Participant Recruitment and Participation (CONSORT Diagram)

EHR, Electronic Health Record; SEE, Support Educate Empower

* One participant was also non-adherent to seizure medications and seized during the counseling session and was disqualified from the study, one had non-diagnosed cognitive issues and was unable to participate, one let us know that she did not have enough time to participate in study visits, one moved, and five were lost to follow-up.

Once a potential participant passed screening, they were invited to participate in a 3- month electronic medication monitoring period to determine study eligibility for the SEE Program. We did this because we wanted an objective measurement of medication adherence to confirm poor adherence status as the SEE Program is resource intensive and would likely only be given to those with truly poor adherence. At the baseline study visit, written informed consent was obtained and participants filled out study surveys. Participants were then given electronic medication adherence monitors for each of their glaucoma medications. Participants who completed 3 months of baseline monitoring and showed poor medication adherence (≤80% of prescribed doses taken on schedule)7 were eligible and invited to participate in the SEE Program. Participants were masked to SEE Program participation adherence criteria. At each of the seven study visits, the participant received $35 for their time spent on survey questions and assessments. This study was approved by the University of Michigan Institutional Review Board and followed all of the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Sample Size Calculation

Sample size estimates were calculated to assess the potential impact of the SEE program pilot study on glaucoma medication adherence. We based our sample size estimates on the work of Okeke and colleauges23 where a 20-percentage point increase in medication adherence was found after a personalized education program among participants with glaucoma with <75% adherence to their glaucoma medications. The SEE program pilot study required enrolling 46 participants with ≤80% adherence to provide 80% power to detect at least a relative improvement of 15% in adherence with a type 1 error of 5%.

Medication Adherence Monitoring

Medication adherence was monitored electronically 24 (AdhereTech, New York, USA) during the 3-month baseline eligibility period and throughout the 7-month SEE Program. The medication adherence monitors look like large pill bottles, and the participants placed each of their glaucoma medications within a separate marked monitoring bottle. Whenever a monitoring bottle is opened, a time-date stamp was sent to our database through the cellular data network and recorded as a medication taking event.

An adherent event was defined as opening the adherence monitor within a specified time window of the dose on the previous day,19 specifically 24±4 hours for medications dosed once per day, 24±2 hours for medications dosed twice per day, and 24±1.3 hours for medications dosed 3 times per day. When calculating adherence for medications dosed more than once a day, we compared the current day’s doses to the previous day’s doses rather than simply the previous dose (e.g., second versus first or third versus second) as lifestyle and sleeping patterns can result in medication times that are not equally spaced.19 For participants on more than 1 medication, adherence was first measured at the medication level and then aggregated to the person level by dividing the total number of doses of all medication(s) taken on time by the total number of doses of all medication(s) prescribed. Adherence was measured during specified time periods as a continuous variable on a scale from 0 to 100, representing the percentage of prescribed glaucoma medications doses that were taken as scheduled.

Adherence was calculated monthly during the 3-month pre-program period and a median of the 3 months of medication adherence was selected as the baseline measure of adherence. Participants whose median baseline adherence was ≤80% were eligible to continue in the study and receive the SEE Program intervention. Because we did not have a control group, we chose to use median adherence as opposed to mean adherence to mitigate the effects of regression to the mean and the Hawthorne effect, or the change in behavior attributed to the knowledge that one is being monitored.25 Adherence was calculated cumulatively over the duration of the SEE Program and also between each in-person SEE Program session.

SEE Program

The SEE Program combines personalized glaucoma coaching sessions delivered by a trained ophthalmic technician or health educator with automated, tailored medication alerts to help people better self-manage their glaucoma. Each glaucoma coach (3) completed a 16-hour glaucoma-specific MI training program 19 and demonstrated that they reached competence as measured by the modified One-Pass among practice participants before coaching study participants.26 Of the three coaches in the study, one was a glaucoma technician, one was a health educator, and one was a social worker. Each coaching session with a study participant was audio-recorded, and a Motivational Interviewing Network of Trainers 27 trainer graded a random 10% of encounters for fidelity to MI using the ONE PASS grading system.26

Participants who demonstrated poor adherence during baseline medication monitoring met with the glaucoma coach, who enabled the medication reminders to light up or have an audible alert when a dose of medication was due. If a participant was more than 1 hour late taking their medication, they could additionally elect to receive an automated phone call or text message reminding them to take their medication. Participants could elect to receive any, all, or none of these reminders. These reminders continued for the entire 7-month SEE Program.

Participants then met with the glaucoma coach for 3 in-person and five over-the-phone coaching and education sessions over 6 months. An in-depth description of the program is provided elsewhere.28 In brief, during the first in-person coaching session, the glaucoma coach used a web-based application to generate tailored glaucoma educational materials and teach eye drop instillation. The application also generates MI-based counseling prompts to guide the conversation between the coach and participant. The coach used a tablet like a story book where the coach turns the tablet towards themselves to read the conversation prompts, and turns the tablet towards the participant to share the personalized audio-visual information (SEE website: https://glaucomaeyeguide.org) The education is tailored on the following variables: name, gender, race/ethnicity, type of glaucoma, glaucoma test results (visual field tests and optic nerve photographs), previous laser or incisional glaucoma surgeries, recommended glaucoma medications, physician’s name, cell phone and internet usage, social support, and barriers to adherence.17 During the first in-person session, the coach helped the participant identify barriers to optimal adherence and used the person’s strengths and motivations to guide potential solutions. Over the course of the counseling session, the coach helped the participant put together a list of questions to ask the doctor at the next visit. At the end of the first session, the coach used the web-application to create a written action plan of the next steps to integrate medication taking into the participant’s daily routine.29–32

During the second in-person session, 2 months later, participants repeated elements of the first session wherein they discussed their motivation to take care of their vision and what strengths they have that they can use to enact their plan, practiced instilling eye drops, and went over their daily routine for eye drop use. In the third in-person session, 2 months later, participants repeated different elements of the first session wherein they chose what parts of the personalized glaucoma education content they wanted to review and discussed any new barriers that may have arisen. Between-session phone calls (5 total; 3 between the first and second sessions, 1 between the second and third sessions, and 1 approximately 1-month after the third session) were tailored to the participant’s current level of adherence and focused on problem solving issues that arose. The glaucoma coaches updated the participant’s ophthalmologist on their adherence status through a note in the electronic health record. Participants could call their coach if questions arose.

Satisfaction with SEE Program

At completion of the SEE Program, a research assistant surveyed participants on their satisfaction with information they received throughout the program. The survey consisted of 3 questions covering the amount, clarity, and helpfulness of information received about glaucoma medications. These questions were scored on a 7-point Likert scale with higher scores indicating more satisfaction. A fourth satisfaction question assessed satisfaction with amount of information where a 7-point Likert scale was anchored in a score of 1 indicating “too little information,” a score of 4 indicating “just the right amount of information,” and a score of 7 indicating “too much information.”

Statistical Analyses

Descriptive statistics (mean, standard deviation [SD], frequency, percentage) were used to summarize participant demographic and clinical characteristics. Participant cohorts (those who passed screening versus failed, those who were eligible after baseline medication adherence monitoring versus ineligible, those who completed the SEE Program versus dropped out) were compared for differences with 2-sample t-tests, chi-square tests, and Fisher exact tests. Descriptive statistics were also used to summarize coaching program including hours of training and supervision of coaches, fidelity of coaches to the SEE Program goals, and amount of counseling given to participants.

Adherence during the baseline monitoring period was investigated for the Hawthorne effect descriptively, with spaghetti plots and locally estimated scatterplot smoothing (LOESS). Paired t-tests were used to compare mean adherence in the first month of baseline monitoring to adherence in the later 2 months to assess whether the impact of knowing one’s adherence is being monitored wanes over time. To reduce the potential impact of the Hawthorne effect or regression to the mean, the baseline measure of adherence was calculated as the median of the 3 individual monthly measures of adherence.

The effect of the SEE Program on glaucoma medication adherence was investigated with paired t-tests, including all pairwise comparisons between baseline adherence, adherence during medication reminders, and adherence during the 3 separate SEE coaching sessions. A linear mixed regression model was used to investigate the effect of an added step of intervention on medication adherence. Statistical analysis was performed with SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Results

The self-reported adherence screening surveys identified 589 participants who were deemed ineligible during screening (good adherence) and 147 who were eligible (poor adherence). Those eligible participants who self-reported poor adherence were significantly younger (mean of 66.4 years [SD=11.0] versus 71.4 years [SD=9.8], p<0.0001), and a larger percentage were of Black race (27.4% versus 14.9%, p<0.0001), compared to participants who self-reported good adherence (Table 1). Of the 147 participants who passed screening, 47 declined participation and the remaining 100 were given electronic monitors to track medication adherence over the 3-month baseline period.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics and comparison of participant samples

| Screening | Baseline Monitoring | SEE Program | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Failed (n=589) | Passed (n=147) | Ineligible (n=47) | Eligible (n=48) | Completed (n=39) | Dropout (n=9) | ||||||||||

| Categorical Variable | # | % | # | % | P-value* | # | % | # | % | P-value* | # | % | # | % | P-value* |

| Gender | |||||||||||||||

| Female | 328 | 55.7 | 72 | 49.0 | 0.14 | 25 | 53.2 | 22 | 45.8 | 0.47 | 17 | 43.6 | 5 | 55.6 | 0.71 |

| Male | 261 | 44.3 | 75 | 51.0 | 22 | 46.8 | 26 | 54.2 | 22 | 56.4 | 4 | 44.4 | |||

| Ethnicity | |||||||||||||||

| Hispanic | 7 | 1.3 | 2 | 1.5 | 1.00 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 2.2 | 0.49 | 1 | 2.7 | 0 | 0.0 | 1.0000 |

| Non-Hispanic | 525 | 98.7 | 134 | 98.5 | 46 | 100.0 | 44 | 97.8 | 36 | 97.3 | 8 | 100.0 | |||

| Race | |||||||||||||||

| Asian | 15 | 2.6 | 12 | 8.2 | <0.0001 | 6 | 10.6 | 3 | 6.3 | 0.10 | 2 | 5.1 | 1 | 11.1 | 0.67 |

| Black | 87 | 14.9 | 40 | 27.4 | 11 | 23.4 | 22 | 45.8 | 19 | 48.7 | 3 | 33.3 | |||

| Other | 10 | 1.7 | 2 | 1.4 | 1 | 2.1 | 1 | 2.1 | 1 | 2.6 | 0 | 0.0 | |||

| White | 472 | 80.8 | 92 | 63.0 | 30 | 63.8 | 22 | 45.8 | 17 | 43.6 | 5 | 55.6 | |||

| Continuous Variable | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | P-value** | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | P-value** | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | P-value** | ||||||

| Age (years) | 71.4 (9.8) | 66.4 (11.0) | <0.0001 | 64.2 (10.8) | 62.4 (10.3) | 0.41 | 63.4 (10.7) | 57.9 (7.4) | 0.15 | ||||||

| Census Tract Income | 71023 (21249) | 68788 (21750) | 0.26 | 76506 (27840) | 53454 (19621) | <0.0001 | 54199 (20664) | 50306 (15000) | 0.60 | ||||||

| Baseline adherence (%) | 59.9 (18.5) | 52.8 (19.7) | 0.31 | ||||||||||||

| Worse eye MD | −7.9 (8.6) | −8.1 (10.2) | 0.95 | ||||||||||||

| # Glaucoma Meds | 1.8 (0.9) | 1.6 (0.9) | 0.45 | ||||||||||||

| Total # Doses Meds | 3.0 (2.1) | 2.2 (1.6) | 0.28 | ||||||||||||

| # Med Reminders | 2.0 (0.9) | 1.3 (1.1) | 0.048 | ||||||||||||

SD, Standard Deviation; MD, Mean Deviation

Chi-square test or Fisher’s Exact test (when cell counts <5)

2-sample, t-test

After baseline monitoring was completed, 48 participants were eligible to continue on to undergo the SEE Program (adherence ≤80%), 47 were ineligible (adherence >80%), and 5 dropped out before completing the monitoring period. Eligible participants had significantly lower median household income than ineligible participants (mean of $53,454 [SD=$19,621] versus $76,506 [SD=$27,840], p<0.0001, Table 1). Finally, of the 48 eligible subjects, 39 completed the SEE Program and 9 (19%) dropped out (2 during the medication reminders phase and 7 after the first SEE coaching session). The only significant difference between participants who completed the SEE Program and those who dropped out were that those who dropped out elected to receive fewer types of medication reminders (mean of 1.3 reminders [SD=1.1] versus 2.0 reminders [SD=0.9], respectively, p=0.048) (Table 1). However, there were no significant differences in proportion of participants who chose each type of reminder between those who dropped out versus completed the SEE Program (lights: 33.3% vs. 66.7%, p=0.13; sound: 33.3% vs. 59.0%, p=0.27); text message: 44.4 % vs. 56.4%, p=0.71; phone call: 22.2% vs. 20.5%, p=1.00). Although the medication adherence data among those who dropped out is somewhat difficulty to interpret as it is not clear if adherence was low because participants dropped out or because participants stopped using the electronic medication monitors, we found that those who dropped out had lower adherence scores compared to those who completed the SEE Program. Adherence during the medication alert phase was 50.1% [SD = 29.6%] among the 7 out of 9 participants who dropped out but still had adherence data compared to 79.2% [SD = 17.6%] among those who completed the SEE Program (2-sample Wilcoxon, p= 0.006).

Three glaucoma coaches provided counseling and education to participants over the course of the SEE Program. The coaches had a range of 16.0 to 29.5 hours of training from a Motivational Interviewing Network of Trainers 27 trainer. The first coach underwent only the glaucoma-specific MI training session and the other 2 coaches completed an additional 2-day general motivational interviewing training. The coaches completed 13.8 to 17 hours of supervision (Table 2). Coaches showed fidelity to MI counseling based on mean ONE PASS scores for their randomly chosen sessions of 5.6 [SD = 0.7], 5.7 [SD = 0.4], and 5.3 [SD = 0.3] for the 3 coaches; a score of ≥5.0 is defined as competent. Coaches spent an average of 127.8 [SD = 32.3] minutes counseling participants in-person over the 3 sessions (range 66–194 minutes, median 126 minutes). The coaches spent an average of 68.2 minutes [SD = 24.5] counseling during the first session, 27.9 minutes [SD = 7.5] counseling during the second session and 31.7 minutes [SD = 12.5] counseling during the third session.

Table 2.

SEE Coaching Training and Fidelity to MI

| Variable | Coach 1 | Coach 2 | Coach 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Training | |||

| Hours Trained | 16 | 29.2 | 29.5 |

| Hours Supervised | 17 | 14.6 | 13.8 |

| Study Participants Fidelity | (n=10) | (n=7) | (n=7) |

| Overall One Pass Score, Mean (SD) | 5.6 (0.7) | 5.7 (0.4) | 5.3 (0.3) |

| % One Pass Score ≥5 | 80% | 100% | 100% |

| % Coach:Participant Talk ≥50% | 80% | 85.7% | 100% |

| % Reflection:Question ≥2:1 | 100% | 100% | 100% |

| % Open-Ended Questions ≥70% | 100% | 100% | 100% |

| % Complex Reflections ≥25% | 100% | 100% | 100% |

| % SEE Tasks Completed ≥75% | 90% | 100% | 100% |

MI, motivational interviewing; SD, Standard Deviation; SEE Support Educate Empower

Of the 95 subjects who completed baseline monitoring, the average baseline medication adherence over months 1, 2, and 3 of monitoring was 77.3% [SD = 18.7%], 72.4% [SD = 22.2%], and 72.9% [SD = 22.2%], respectively (Supplemental Table 1, Supplemental Figure 1, available at http://www.aaojournal.org). Adherence during the first month of monitoring was significantly better than during month 2 (p<0.0001) and month 3 (p=0.008), but no significant difference in adherence was observed between months 2 and 3 of monitoring (p=0.72).

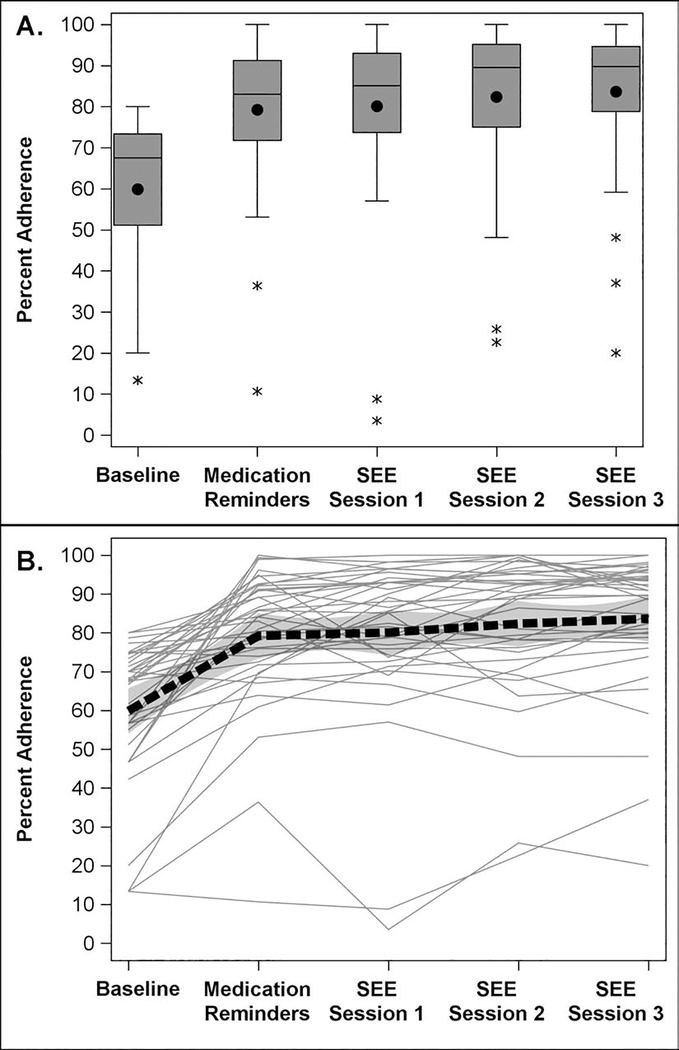

For the 39 eligible participants who completed the SEE Program, baseline adherence was on average 59.9% [SD = 18.5%] which improved to 79.2% (SD = 17.6%; p<0.0001) one month after initiating the medication reminders. Adherence improved further, over that observed under medication reminders, to 80.1% (SD = 20.6%; p=0.58), 82.4% (SD = 18.6%; p=0.049), and 83.6% (SD = 17.5%; p=0.020) in the two month periods after each of the 3 SEE coaching sessions, respectively (Table 3; Figure 2). Cumulative adherence over the entire 7-month SEE Program was on average 81.3% [SD=17.6%] and significantly improved from average baseline adherence of 59.9% (p<0.0001). Participants showed an average relative improvement in adherence of 21.4% during the SEE Program (SD = 16.5%, range=−3.2% to 74.4%, p<0.0001). Participants improved (defined as any change >0) upon their baseline medication adherence in 95% of cases (n=37 of 39) and 59.0% of participants had adherence >80% upon completing the SEE Program. A linear mixed regression model found that each added step of intervention (medication reminders to SEE coaching session 1, or an additional session of coaching) was associated with a 1.8% (95% CI, 0.8%−2.7%; p=0.0003) increase in medication adherence over the improvement in adherence one month after initiating the personalized reminders, so that after the three coaching sessions, there was a 5.4% increase in medication adherence attributable to the coaching sessions.

Table 3.

Glaucoma Medication Adherence Before and After the SEE program

| Adherence Time | N | Mean | SD | Min | Max | Median | P-value* | P-value** | P-value*** | P-value**** |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eligible Cohort (n=48) | ||||||||||

| Baseline (3 months) | 48 | 58.5% | 18.7% | 13.3% | 80.0% | 66.7% | ||||

| Medication Reminders (1 month) | 46 | 74.8% | 21.6% | 10.7% | 100.0% | 79.2% | <0.0001 | |||

| SEE Session 1 (2 months) | 43 | 79.2% | 20.4% | 3.5% | 100.0% | 85.1% | <0.0001 | 0.2340 | ||

| SEE Session 2 (2 months) | 39 | 82.4% | 18.6% | 22.6% | 100.0% | 89.5% | <0.0001 | 0.0485 | 0.0969 | |

| SEE Session 3 (2 months) | 39 | 83.6% | 17.5% | 20.0% | 100.0% | 89.7% | <0.0001 | 0.0199 | 0.0326 | 0.1767 |

| Complete Cohort (n=39) | ||||||||||

| Baseline (3 months) | 39 | 59.9% | 18.5% | 13.3% | 80.0% | 67.5% | ||||

| Medication Reminders (1 month) | 39 | 79.2% | 17.6% | 10.7% | 100.0% | 83.0% | <0.0001 | |||

| SEE Session 1 (2 months) | 39 | 80.1% | 20.6% | 3.5% | 100.0% | 85.1% | <0.0001 | 0.5759 | ||

| SEE Session 2 (2 months) | 39 | 82.4% | 18.6% | 22.6% | 100.0% | 89.5% | <0.0001 | 0.0485 | 0.0969 | |

| SEE Session 3 (2 months) | 39 | 83.6% | 17.5% | 20.0% | 100.0% | 89.7% | <0.0001 | 0.0199 | 0.0326 | 0.1767 |

SD, standard deviation; Min, Minimum; Max, Maximum; SEE, Support Educate Empower Paired t-test compared to

baseline

medication reminders

SEE Session 1

SEE Session 2

Figure 2.

a. Distribution of medication adherence before and during the Support, Educate, Empower (SEE) Program personalized glaucoma coaching intervention for the 39 participants who completed the intervention using boxplots. Mean and 95% confidence intervals are displayed.

b. Distribution of medication adherence at baseline and during the study period for the 39 subjects completing the Support, Educate, Empower (SEE) Program personalized glaucoma coaching intervention using a Spaghetti plot. A locally estimated scatterplot smoothing (LOESS) curve is represented by the black dashed line. Mean and 95% confidence intervals are displayed.

Overall, participants who completed the SEE Program were very satisfied with the information they received. Most participants (86.8%) reported that information was a score of 6 or 7 (extremely clear/extremely helpful). The majority (60.5%) of participants reported that they felt they received just the right amount of information from the SEE Program. All participants (100%) gave a score of 6 or 7 (completely understand) when questioned about their understanding of how to take their glaucoma medications. (Supplemental Table 2, available at aaojournal.org).

Discussion

The SEE Program of personalized glaucoma coaching demonstrated both feasibility and initial efficacy. Those who completed the program had an average of a 21-percentage point improvement in adherence (baseline adherence: 59.9%, cumulative SEE Program adherence 81.3%). As part of our baseline work for this study, we interviewed 25 glaucoma specialists who were members of the American Glaucoma Society to identify what experts in the field consider a clinically meaningful improvement in adherence. The average improvement thought to be clinically meaningful among these glaucoma specialists was a 17.7 percentage point (95% CI 14.6–20.8) improvement in glaucoma medication adherence. Using an approach that included all 4 components that a Cochrane review of medication adherence interventions identified as leading to behavior change— basing the intervention in behavioral theory; personalized education; Ml-based counseling, and reminder systems—15, 33 did indeed change behavior in our cohort of poorly adherent glaucoma patients in a clinically meaningful way by 21 percentage points. The SEE Program’s multi-pronged approach exhibited a dose-response effect: each time the coach met with the participant, adherence scores increased by a mean of 1.8 percentage points. Participants overall reported excellent satisfaction with the information they received from the SEE Program.

The alarms and text messages were initiated first, and one month later, the participants began the personalized glaucoma coaching sessions. The alarms and text messages continued for the entirety of the 7-month coaching program and had a substantial impact on adherence. However, it was not possible to tease apart whether the alarms alone would have led to sustained improvement in medication adherence as the study was not designed to answer this question. Though alarm studies in large randomized controlled trials outside of ophthalmology have not demonstrated significant improvement in medication adherence,34,35 a previous alarm study for glaucoma patients did demonstrate significant impact on adherence.16 Boland and colleagues demonstrated a substantial benefit to alarms only in improving medication adherence among a subset of patients who engaged with an alarm intervention. In their randomized controlled trial comparing daily text or voice message reminders to take a daily prostaglandin analogue dose compared to usual care, 47% of those randomized to the alarm intervention dropped out (n=18/28) while 40% of those randomized to the usual care intervention dropped out (n=13/32). However, those who completed the intervention had a substantial improvement in glaucoma medication adherence, (from 54% to 73% p <0.05) whereas the control group had no improvement in adherence (from 51% to 46%). To draw a parallel with our study, though the initial 20-percentage point improvement in adherence seen after turning on the alarms and reminders for the month before the coaching sessions had formally begun was substantial, after each coaching session, participants had an additional significant increase in adherence of 1.8 percentage points. Moreover, our drop-out rate was less than half of that seen in Boland’s study (19% vs 47%). This represents a very different level of engagement with the intervention, where poorly adherent glaucoma patients not only continued to participate in the program, but also had significant increases in their adherence after each interaction with the glaucoma coach. The large and sustained success of the alarms in our study must not be examined out of the context of the very positive relationship formed with the glaucoma coach. In exit interviews, 97% (n=38/39) of participants mentioned the importance of the glaucoma coach in improving their glaucoma medication adherence compared to 72% (n=28/39) who mentioned that the alerts and reminders improved their adherence. In-depth qualitative analysis of the participants’ experience in the SEE Program will be presented in a companion manuscript.

Additionally, we cannot know whether the large increase in adherence would have also been seen had the counseling session been given first and the alarms added later, but we chose to use the alarms first as a less resource intensive intervention. When implementing additional support for glaucoma medication adherence, we may take a stepped approach where alarms and alerts are used first and then coaching is added for those who do not improve or do not sustain an improvement in medication use behavior. This may enable a stepped version of increased self-management support, where all glaucoma patients could be enrolled in automated medication reminders, but only those who disengage from the reminders, score poorly on self-reported measures of adherence, or do not refill their glaucoma medications would be referred for the more intensive glaucoma self-management support program with the personalized glaucoma coaching.

All 3 coaches met competence standards and maintained fidelity to MI principles throughout the intervention, demonstrating the efficacy of the SEE Program training and supervision protocol. Researchers have identified that MI only works to help participants change their behavior if the counselor delivers high quality counseling that is consistently autonomy- supportive. 36,38 A recent meta-analysis 37 of studies investigating the impact of MI on medication adherence found that MI counselors who underwent a fidelity assessment of their MI skills had a significant impact on improving medication adherence compared to those without this assessment. Whether just the knowledge of being continuously assessed or the feedback given during the assessment led to improved counseling was not clear, but the finding reinforces the value of counseling that has high fidelity to MI principles. The coaches in the SEE Program received 16 hours of initial glaucoma specific MI training, 14–17 hours of supervision, and 2 coaches received a 14 hour additional general MI training session over the entire 1 year, 8 month SEE Program study. This level of training and supervision was similar to that given to lay health care workers in an MI-based sexual risk reduction intervention in South Africa. Investigators found that all lay health care workers were not delivering consistent MI counseling after an initial 35-hour training, but the majority improved greatly in their adherence to MI principles after 18 hours of refresher training and continued supervision.39

Our findings also suggest the value of using technology, such as eHealth tools, to expand the amount of support para-professional staff are able to provide participants. The SEE Program web application is an eHealth tool that generates personalized educational content and audio-visual materials (e.g. diagnosis, doctor’s recommendations, barriers to optimal self-management) alongside prompts to guide the MI-based conversation. The prompts can be hidden if the coach feels comfortable guiding the conversation without them. In an eHealth intervention focused on improving diabetes outcomes, lay healthcare workers used a similar interactive tablet-based program to provide individualized diabetes information to low-income Latino and African American adults with diabetes. This intervention led to an improvement in glycemic control comparable to prescribing an additional oral hypoglycemic agent.40 The effect of integrating MI-based prompts into an eHealth tool can greatly augment the counseling abilities of para-professional staff.

Two prior National Eye Institute-funded randomized controlled trials have addressed self-management support for glaucoma medication adherence using some of these principles. The first program used tailored, automated phone calls and printed materials to provide glaucoma education. Though there was no differences between the intervention and control groups, self-reported adherence improved in both arms, demonstrating how increased attention improved medication taking behavior.41 The second study intervention used: (1) a licensed clinical psychologist to deliver an hour long in-person MI-based counseling session, (2) glaucoma education culturally tailored to African-Americans, and (3) 3 weekly follow-up phone calls.42 This intervention demonstrated a significant 15 percentage-point improvement over baseline in medication adherence among 11 participants after the 4-week program. The SEE Program utilized these same successful principles— MI-based counseling, glaucoma education, and follow-up support— and made the program more scalable by having the web application personalize the glaucoma education and having a para-professional coach deliver the counseling instead of a licensed psychologist.

In order to test the impact of the SEE Program, we aimed to recruit participants with poor medication adherence, as it is unlikely that the medical system would reimburse for self-management support services in participants who have good medication adherence. We found that using 2 surveys of self-reported adherence identified that only 20% of people (147/736) willing to participate in the study had poor adherence. In a systematic review of glaucoma medication adherence literature, Reardon and colleagues found 33% of participants did not fill their glaucoma medications 12 months after starting therapy. In a claims analysis of 1,234 newly diagnosed glaucoma participants, only 15% had a medication possession ratio of 75% over 4 years of follow-up. 43 Thus, it seems that either glaucoma participants in our study were overestimating their adherence 44 or we are seeing evidence of the healthy volunteer effect, where those who are healthier are more likely to volunteer for clinical research. Of those who passed screening with poor self-reported adherence, 68% (100/147) agreed to participate in the study, which is similar to the 70% participation rate among eligible recruits for randomized controlled trials in the United Kingdom. 45

It seems that knowing one’s adherence was being monitored, or the Hawthorne effect, did have a short term impact on participant behavior in two ways. Initially, we chose to monitor adherence for 3 months prior to the intervention because the Hawthorne effect was found to wane after 2 months of monitoring in a previous study of glaucoma medication adherence.25 In our study cohort, we found that after 1 month of monitoring, participants’ adherence decreased significantly from an average of 77.3% to 72.4% (p<0.0001) but then did not decrease from month 2 to month 3 (72.4% to 72.9%, p=0.7). This suggests that the majority of the Hawthorne effect - or an improvement in medication taking behavior because of the knowledge that the behavior is being observed - waned after 1 month of electronic medication monitoring. However, there did seem to be an impact of monitoring medication use on medication taking behavior itself, as 47/100 participants with poor self-reported medication use at had electronically monitored adherence over 80%. Those whose adherence was ≥80% during the 3- month monitoring period were more likely to have higher median household income ($76,506 vs $53,454, p<0.0001). This behavior change may have been due to the knowledge of being monitored, or perhaps may have come from answering many survey questions assessing glaucoma knowledge, medication taking behavior, confidence in taking control of one’s health status or from meeting with the study team personnel and being given the extra attention and focus on glaucoma medication adherence.

This pilot study’s strengths lie in 1) its rigorous assessment of medication adherence using electronic medication monitoring; 2) using medication adherence monitors that sent data through the cellular network so that those without internet access could be included; 3) the rigorous assessment of and maintenance of fidelity to motivational interviewing-style counseling; 4) the 3-month baseline adherence monitoring period to mitigate possible Hawthorne effect and regression to the mean on the main outcome measure; and 5) the inclusion of a substantial percentage of study participants who were women (46%) and who were African-American (46%). The study also had several limitations. As a pilot study, it was limited in that it did not include a control group comparator. In addition, the electronic medication monitors only accurately assess adherence if participants place their glaucoma medications into the bottles. Thus, it can appear that a participant is less adherent than they truly are. Having three glaucoma coaches coach the participants could have lent variability to the intervention; however, all three coaches did attain and maintain competence in MI-based counseling. Additionally, it is not possible to disentangle the contribution of each component of the SEE Program on adherence using a pre-post design. If the program has demonstrated efficacy in an RCT but is too costly or too burdensome for implementation, future work will tease apart the “active ingredients” using an RCT with a fractional factorial design.

Conclusions

The SEE Program, a multi-pronged, evidence-based intervention combining medication alarms/alerts, MI-based coaching, personalized glaucoma education and between-visit support, significantly improved medication adherence among poorly-adherent glaucoma patients. The results support further evaluating its effectiveness and scalability in a large-scale, multi-site randomized controlled clinical trial. This type of evidence would also enable cost-effectiveness studies of such a personalized coaching intervention.

Supplementary Material

Supplemental Figure 1. Spaghetti plot of medication adherence over a 3-month baseline monitoring period (n=95). A locally estimated scatterplot smoothing (LOESS) curve is represented by the black dashed line. (Available at https://www.aaoiournal.org)

Precis.

A glaucoma self-management support program that combined motivational-interviewing based counseling, personalized education, between-visit support and reminders lead to a 21.4% increase in electronically monitored glaucoma medication adherence compared to baseline.

Acknowledgments

This work will be presented in part at: The American Glaucoma Society Annual Meeting, Washington DC, February 29, 2020

Funding Agency: National Eye Institute (K23EY025320, PANC) and Research to Prevent Blindness Career Development Award (PANC). The funding organizations had no role in the design or conduct of this research.

Abbreviations

- SEE Program

Support, Educate and Empower Program

- MI

motivational interviewing

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: No conflicting relationships exist for any author.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bourne RRA, Stevens GA, White RA, et al. Causes of vision loss worldwide, 1990–2010: a systematic analysis. Lancet Glob Heal. 2013;1:e339–e349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization. Blindness and Vision Impairment Prevention: Priority Eye Diseases, Glaucoma. https://www.who.int/blindness/causes/priority/en/index6.html.

- 3.Olthoff CMG, Schouten JSAG, van de Borne BW, Webers CAB. Noncompliance with ocular hypotensive treatment in patients with glaucoma or ocular hypertension an evidence-based review. Ophthalmology. 2005;112:953–961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Reardon G, Kotak, Schwartz GGF, Kotak S, Schwartz GGF. Objective assessment of compliance and persistence among patients treated for glaucoma and ocular hypertension: A systematic review. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2011; 5:441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Newman-Casey PA, Blachley T, Lee PP, Heisler M, Farris KB, Stein JD. Patterns of glaucoma medication adherence over four years of follow-up. Ophthalmology. 2015;122:2010–2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Friedman DS, Hahn SR, Gelb L, et al. Doctor-Patient Communication, Health-Related Beliefs, and Adherence in Glaucoma. Ophthalmology. 2008;115:1320–1327.e3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sleath B, Blalock S, Covert D, et al. The Relationship between Glaucoma Medication Adherence, Eye Drop Technique, and Visual Field Defect Severity. Ophthalmology. 2011;118:2398–2402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sleath B, Sayner R, Blalock SJ, et al. Patient Question-Asking About Glaucoma and Glaucoma Medications During Videotaped Medical Visits. Health Commun. 2015;30:660–668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rossi GCM, Pasinetti GM, Scudeller L, Radaelli R, Bianchi PE. Do Adherence Rates and Glaucomatous Visual Field Progression Correlate? Eur J Ophthalmol. 2011;21:410–414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Newman-Casey PA, Niziol LM, Gillespie BW, Janz NK, Lichter PR, Musch DC. The Association between Medication Adherence and Visual Field Progression in the Collaborative Initial Glaucoma Treatment Study. Ophthalmology. January 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lacey J, Cate H, Broadway DC. Barriers to adherence with glaucoma medications: a qualitative research study. Eye. 2009;23:924–932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stryker JE, Beck AD, Primo SA, et al. An Exploratory Study of Factors Influencing Glaucoma Treatment Adherence. J Glaucoma. 2010;19:66–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Taylor SA, Galbraith SM, Mills RP. Causes Of Non-Compliance With Drug Regimens In Glaucoma Patients: A Qualitative Study. J Ocul Pharmacol Ther. 2002;18:401–409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tsai JC, McClure CA, Ramos SE, Schlundt DG, Pichert JW. Compliance barriers in glaucoma: a systematic classification. J Glaucoma. 2003;12:393–398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nieuwlaat R, Wilczynski N, Navarro T, et al. Interventions for enhancing medication adherence. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;11 :CD000011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Boland M V, Chang DS, Frazier T, Plyler R, Jefferys JL, Friedman DS. Automated Telecommunication-Based Reminders and Adherence With Once-Daily Glaucoma Medication Dosing. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2014;132:845–850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kreuter M, Farrell D, Olevitch L, Brennan L. What is Tailored Communication? In: Tailoring Health Messages: Customizing Communication with Computer Technology. Mahaw, NJ: Routledge; 2000:1–23. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Miller WR, Rollnick S. Meeting in the middle: motivational interviewing and selfdetermination theory. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2012;9:25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Newman-Casey PA, Killeen O, Miller S, et al. A Glaucoma-Specific Brief Motivational Interviewing Training Program for Ophthalmology Para-professionals: Assessment of Feasibility and Initial Patient Impact. Health Commun. December 2018:1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chang DS, Friedman DS, Frazier T, Plyler R, Boland M V. Development and Validation of a Predictive Model for Nonadherence with Once-Daily Glaucoma Medications. Ophthalmology. 2013;120:1396–1402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Morisky DE, Green LW, Levine DM. Concurrent and Predictive Validity of a Self-reported Measure of Medication Adherence. Med Care. 1986;24:67–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Krousel-Wood M, Islam T, Webber LS, Re RN, Morisky DE, Muntner P. New medication adherence scale versus pharmacy fill rates in seniors with hypertension. Am J Manag Care. 2009;15:59–66. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Okeke CO, Quigley HA, Jampel HD, et al. Interventions Improve Poor Adherence with Once Daily Glaucoma Medications in Electronically Monitored Patients. Ophthalmology. 2009;116:2286–2293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Blaschke TF, Osterberg L, Vrijens B, Urquhart J. Adherence to Medications: Insights Arising from Studies on the Unreliable Link Between Prescribed and Actual Drug Dosing Histories. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2012;52:275–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ajit RR, Fenerty CH, Henson DB. Patterns and rate of adherence to glaucoma therapy using an electronic dosing aid. Eye. 2010;24:1338–1343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McMaster F, Resnicow K. Validation of the one pass measure for motivational interviewing competence. Patient Educ Couns. 2015;98:499–505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Welcome to the Motivational Interviewing Website! | Motivational Interviewing Network of Trainers (MINT). https://motivationalinterviewing.org/.

- 28.Newman-Casey PA, Niziol LM, Mackenzie CK, et al. Personalized behavior change program for glaucoma patients with poor adherence: a pilot interventional cohort study with a pre-post design. Pilot Feasibility Stud. 2018;4:128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gollwitzer PM. Implementation intentions: Strong effects of simple plans. Am Psychol. 1999;54:493–503. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gollwitzer PM, Brandstatter V. Implementation intentions and effective goal pursuit. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1997;73:186–199. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Liu LL, Park DC. Aging and Medical Adherence: The Use of Automatic Processes to Achieve Effortful Things. Psychol Aging. 2004;19:318–325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nadkarni A, Kucukarslan SN, Bagozzi RP, Yates JF, Erickson SR. Examining determinants of self management behaviors in patients with diabetes: An application of the Theoretical Model of Effortful Decision Making and Enactment. Patient Educ Couns. 2011;85:148–153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Waterman H, Evans JR, Gray TA, Henson D, Harper R. Interventions for improving adherence to ocular hypotensive therapy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;30:CD006132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Choudhry NK, Krumme AA, Ercole PM, et al. Effect of Reminder Devices on Medication Adherence. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177:624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Volpp KG, Troxel AB, Mehta SJ, et al. Effect of Electronic Reminders, Financial Incentives, and Social Support on Outcomes After Myocardial Infarction. JAMA Intern Med. 2017; 177:1093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Leahey TM, Wing RR. A randomized controlled pilot study testing three types of health coaches for obesity treatment: Professional, peer, and mentor. Obesity. 2013;21:928–934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Palacio A, Garay D, Langer B, Taylor J, Wood BA, Tamariz L. Motivational Interviewing Improves Medication Adherence: a Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. J Gen Intern Med. 2016;31:929–940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ostlund A-S, Wadensten B, Haggstrom E, Lindqvist H, Kristofferzon M-L. Primary care nurses’ communication and its influence on patient talk during motivational interviewing. J Adv Nurs. 2016;72:2844–2856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dewing S, Mathews C, Cloete A, Schaay N, Simbayi L, Louw J. Lay counselors’ ability to deliver counseling for behavior change. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2014;82:19–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Spencer MS, Kieffer EC, Sinco B, et al. Outcomes at 18 Months From a Community Health Worker and Peer Leader Diabetes Self-Management Program for Latino Adults. Diabetes Care. 2018;41:1414–1422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Glanz K, Beck AD, Bundy L, et al. Impact of a Health Communication Intervention to Improve Glaucoma Treatment Adherence. Arch Ophthalmol. 2012;130:1252–1258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dreer LE, Owsley C, Campbell L, Gao L, Wood A, Girkin CA. Feasibility, Patient Acceptability, and Preliminary Efficacy of a Culturally Informed, Health Promotion Program to Improve Glaucoma Medication Adherence Among African Americans: “ G laucoma Management O ptimism for A frican Americans L iving with Glaucoma. Curr Eye Res. 2016;41:50–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Newman-Casey PA, Blachley T, Lee PP, Heisler M, Farris KB, Stein JD. Patterns of Glaucoma Medication Adherence over Four Years of Follow-Up. Ophthalmology. 2015;122:2010–2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kass MA, Gordon M, Morley RE, Meltzer DW, Goldberg JJ. Compliance with topical timolol treatment. Am J Ophthalmol. 1987;103:188–193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Walters SJ, Bonacho dos Anjos Henriques-Cadby I, Bortolami O, et al. Recruitment and retention of participants in randomised controlled trials: a review of trials funded and published by the United Kingdom Health Technology Assessment Programme. BMJ Open. 2017;7:e015276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental Figure 1. Spaghetti plot of medication adherence over a 3-month baseline monitoring period (n=95). A locally estimated scatterplot smoothing (LOESS) curve is represented by the black dashed line. (Available at https://www.aaoiournal.org)