Abstract

Background:

Assessing the degree of myelin injury in patients with multiple sclerosis (MS) is challenging due to lack of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) methods specific to myelin quantity. By measuring distinct tissue parameters from a two-pool model of the magnetization transfer (MT) effect, quantitative MT (qMT) may yield these indices. However, due to long scan times, qMT has not been translated clinically.

Objectives:

We aim to assess the clinical feasibility of a recently optimized selective inversion recovery (SIR) qMT and to test the hypothesis that SIR-qMT derived metrics are informative of radiological and clinical disease-related changes in MS.

Methods:

Eighteen MS patients and nine age-sex matched heathy controls (HCs) underwent a 3.0 Tesla (3T) brain MRI, including clinical scans and an optimized SIR-qMT protocol. Four subjects were re-scanned at a 2-week interval to determine inter-scan variability.

Results:

SIR-qMT measures differed between lesional and non-lesional tissue (p<0.0001) and between normal appearing white matter (NAWM) of patients with more advanced disability and normal WM of HCs (p<0.05). SIR-qMT measures were associated with lesion volumes, disease duration, and disability scores (p≤0.002).

Conclusions:

SIR-qMT at 3T is clinically feasible and predicts both radiological and clinical disease severity in MS.

Introduction

Neurodegeneration, featured by myelin and axonal damage, is a key pathological feature of multiple sclerosis (MS).1 Yet, quantifying myelin injury in vivo is challenged by the lack of a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) biomarker specific to myelin quantity.2

The magnetization transfer ratio (MTR),3 derived from MT imaging, provides an indirect, but clinically feasible, measurement of myelin integrity.4 However, while indicative of changes in myelin quantity, MTR’s pathological specificity is fraught by non-physiological factors (e.g., sequence timings, scanner hardware)7,10,11 that challenge standardizing MTR for large-scale, multi-site clinical trials.5 In addition, aside from myelin content, MTR is sensitive to changes in axonal density,6 inflammation/edema,7 and infiltrates of macrophages8 and activated microglia.9

In contrast, quantitative MT (qMT) approaches12–14 measure distinct tissue parameters (e.g., the macromolecular-to-free proton pool-size-ratio [PSR]) from a two-pool model of the MT effect and derive indices more closely related to myelin content.15–17 Pulsed saturation qMT10 is the most commonly used qMT method for clinical systems because it allows qMT data to be collected within clinically feasible acquisition times. Unfortunately, this approach suffers from the need to acquire and co-register additional data (e.g., maps of the main magnetic field, the transmit radio frequency field, and the spin-lattice relaxation time), resulting in a complicated data analysis pipeline. To alleviate these issues, the selective inversion recovery (SIR) qMT13,18–21 technique was developed. SIR-qMT is based on a simple two-pool model of inversion recovery data that does not require additional measurements. Using this technique, all the data necessary to estimate qMT parameters are contained within SIR acquisitions at different inversion times.

The primary drawback of the SIR method is the long scan times required to obtain data at multiple inversion times.20 This issue has been addressed by the development of an optimized sampling scheme that allows for estimation of SIR parameters from images acquired at only four optimized inversion times, when the MT exchange rate (kmf) is assumed prior to fitting.22 Although subtle variations have been observed in kmf within patients with MS, presumably related to changes in the integrity of the myelin sheath,23preliminary findings22 suggest that assuming a fixed kmf has little effect on other SIR parameters when optimized sampling schemes are used.

Here we propose to test the impact of these optimized SIR sampling schemes and model assumptions (i.e., fixing kmf during fitting) on estimates of PSR and the spin-lattice relaxation rate of free water (R1f) in a cohort of patients with MS. PSR and R1f are complementary, as both measures are sensitive to the relative quantity of macromolecules, which is primarily reflective of total myelin content in white matter (WM).15–17 R1f is also sensitive to iron content and, therefore, may provide additional information on MS pathological features associated with demyelination.

Because myelin injury is a fundamental aspect of MS pathology and SIR-derived indices are sensitivity to myelin integrity, we hypothesize that indices derived from our optimized SIR protocols are reproducible and sensitive to different degrees of pathological changes (as defined by in vivo gold standard radiological measures), and provide evidence for the severity of neurological dysfunction in patients.

Materials and Methods

Study design and cohort

The study was approved by the local Institutional Review Board, and a signed consent was obtained prior to all examinations. Eighteen patients with MS and nine age- and sex matched healthy controls (HCs) with no contraindications to a research brain MRI and no comorbidities potentially biasing the results were consecutively enrolled over a 6-month time period (Table 1). For patients, the following inclusion criteria were considered: (1) clinically isolated syndrome (CIS), relapsing remitting (RR), or secondary progressive (SP) MS;24,25 (2) ≥3 months free from clinical relapse, administration of steroids, and changes in disability scores; (3) and a clinical post-contrast MRI scan within three months showing no active lesions. All participants underwent a brain MRI and patients had an additional clinic visit to rate disability using the Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS)26 and the Timed 25-Foot Walk Test (T25-FW).27 Four subjects were imaged twice, 2 weeks apart, to assess inter-scan variability in SIR-qMT metrics.

Table 1:

Demographic, clinical and MRI characteristics of the study cohort

| Patients (n=18) | HCs (n=9) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 45.5±14.6 | 41.7±10 | >0.05 |

| Sex (females/males) | 13/6 | 5/4 | >0.05 |

| Ethnicity | 2 African American 17 Caucasians |

8 Caucasians 1 Asian |

-- |

| MS type (CIS/RRMS/SPMS) | 4/11/3 | -- | -- |

| Disease duration (years) | 12.1±10.6 | -- | -- |

| EDSS score*** | 1 (0 −6.5) | -- | -- |

| T25-FW (seconds)**** | 10:37±18:12 | -- | -- |

| T2-lesions volume (cm3) | 14.9±21.3 | -- | -- |

| cBHs volume (cm3) | 7.3±7.5 | -- | -- |

Data are expressed in mean±standard deviation unless otherwise specified; cBHs=chronic black holes; CIS=clinically isolated syndrome; EDSS= Expanded Disability Status Scale; HCs=healthy controls; RRMS=relapsing remitting multiple sclerosis; SPMS=secondary progressive multiple sclerosis; T25-WF= Timed 25-Foot Walk Test.

by Mann-Whitney

by chi-squared test

median (minimum-maximum value)

averaged across 2 trials.

MRI acquisition protocol

Scans were acquired using a whole-body 3T Achieva MRI scanner (Philips Healthcare, Best, The Netherlands) equipped with a volume transmit and 32-channel receive head coil (NOVA Medical, Wilmington, MA). The scanning protocol used for the cross-sectional study included: T1-weighted (T1-w) and T2-w turbo spin echo (TSE), and T2-w Fluid Attenuated Inversion Recovery (FLAIR) sequences, all of which covered the whole brain at a resolution of 0.4×0.4×2 mm3. Additional SIR-qMT were performed with the parameters listed in Table 2.

Table 2:

SIR-qMT, SMT, and MTI acquisition protocol

| SIR-qMT | MTR |

|---|---|

| Coverage = 25 slices for controls, 16–25 | Coverage = whole brain |

| slices in patients (depending upon lesion | Multiple slices |

| distribution and available scan time) | 3D MT-prepared spoiled gradient echo |

| 2D SIR sequence with TSE readout | TR = 135 ms |

| TE = 80 ms | TE = 4.6 ms |

| TI = 10, 10, 278, 1007 ms | MT pulse duration 25ms and frequency |

| TD = 684, 4171, 2730, 10 ms | offset 100,000 Hz |

| TSE factor = 26 | Flip angle = 18 degrees |

| Echo spacing = 5.9 ms | Resolution = 1.5×1.5×3 mm3 |

| SENSE factor = 2.2 | B1 13.5uT |

| Resolution = 2×2×4 mm3 (no gap) | Duration ~ 3 minutes |

| Duration ~ 1 minute/slice |

TD= pre-delay time from end of turbo spin echo (TSE) readout until next inversion pulse; TE=echo time; TI=inversion time; TR=repetition time.

Image post-processing and analysis

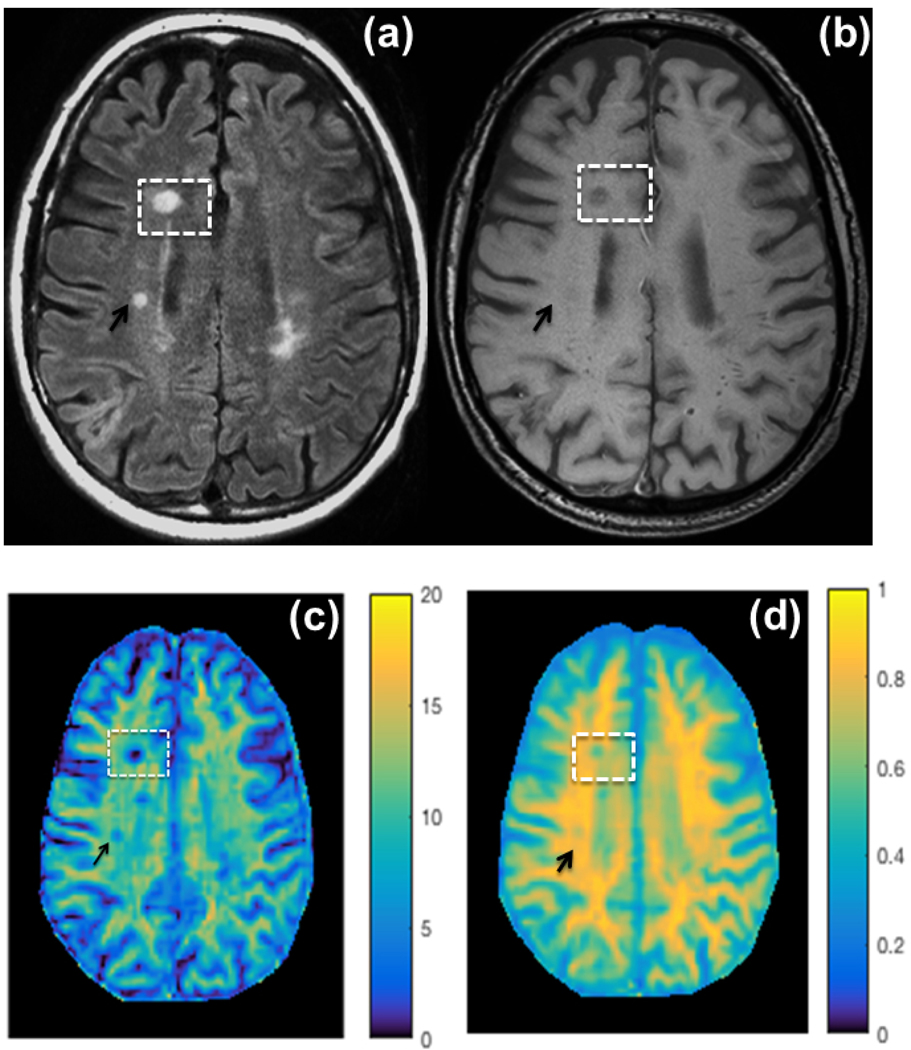

PSR and R1f maps (Figure 1) were derived from SIR-qMT following the procedures previously reported.18,19 Thereafter, T1-w TSE, T2-w FLAIR and SIR parameter maps (PSR and R1f) were co-registered to the T2-w TSE image using an affine co-registration (FLIRT in FSL toolbox, https://fsl.fmrib.ox.ac.uk/fsl/). Two types of images analyses were performed thereafter.

Figure 1: Clinical scans and parametric maps Side by side.

(a) T1-weighted turbo spin echo (T1-w TSE), (b) T2-w Fluid Attenuated Inversion Recovery (FLAIR), sequences, and color-coded (c) macromolecular to free water pool-size-ratio (PSR, %) and maps of (d) spin-lattice relaxation rate of water (R1f, seconds−1). The visibility of a non-acute black hole (BH, white rectangle) and a T2-lesion (black arrow) is highlighted on each map of this representative case.

First, to assess differences in PSR and R1f between regions with different MRI appearance in patients, regions of interest (ROIs) were generated for T2-lesions,28 (non-acute) black holes (BHs)29 and normal appearing white matter (NAWM). Each ROI was compared with the anatomically matched contra-lateral ROI to minimize the impact of anatomical variation in myelin quantity across different brain regions. To assess differences between NAWM in patients and NWM in HCs, ROIs were selected in a representative tract, the internal capsula. In all cases ROIs were manually delineated and correspondent PSR/R1f values were computed using graphic and mathematical tools available in MIPAV (https://mipav.cit.nih.gov/).

Second, to determine the associations between clinical and MRI variables, PSR and R1f were quantified in the entire lesional and non-lesional burden. First, a mask covering all the hyper-intense lesions on T2-w MRIs was manually created (Fig. 2a). Second, BHs were manually delineated in the T1-w scans (Fig. 2b). Last, “subtraction masks”, (i.e., all hyper-intense lesions on T2w MRIs not including BHs, Fig. 2c) were generated using mathematical tools available in MATLAB (Mathworks, Natick, Massachusetts). This process ensured that the final T2-lesion mask did not include BHs. The generated masks were then overlaid on the PSR (Fig. 2d) and R1f (Fig. 2e) maps, and corresponding quantities were derived in MIPAV. Total NAWM and NWM masks were also automatically generated via FSL’s FAST algorithm30 (after subtracting the manually-defined entire lesion burden in patients), and histogram analyses were performed within anatomically-matched slices in the higher-resolution anatomical space of each subject.

Figure 2: Schematic representations of lesions delineation.

Methodology employed for lesions identification: all T2 hyper-intense lesions were first delineated on T2-w FLAIR sequences (a, green regions of interest or ROIs); non-acute black holes (BHs) were delineated on T1-w TSE (b, yellow ROIs). Thereafter, a subtraction mask was created to ensure that lesions counted as T2-lesions did not include BHs (c, blue ROIs). These generated T2-lesions (blue ROIs) and BHs (yellow ROIs) masks were then overlaid on PSR (d) and R1f (e) parametric maps and correspondent quantities derived.

For inter-scan repeatability analysis, both scans’ PSR and R1f were co-registered to the T2-w FLAIR scan from the initial MRI session, allowing 10 identical ROIs per pair of scans to be selected in NAWM/NWM/lesions. It should be noted that this required up-sampling both images to the higher-resolution FLAIR space, which can result in interpolation errors across the scan and rescan data; however, we expect these errors to be small compared to potential errors associated with defining ROIs for each FLAIR scan individually.

Statistical Analysis

Differences in age and sex between patients and HCs were assessed using t-tests and a Chi-square test, respectively. Generalized linear mixed models for binary outcome were used to assess differences in each of the MRI metrics between different tissues types. In these models, the type of MR measurement (PSR and R1f) was treated as a fixed-effect factor, and a nested random effect factor for ROI and patient ID was included to take into consideration the data correlation structure. The magnitude of observed differences for PSR/R1f was assessed using the Akaike information criterion (AIC).

Associations between MRI and clinical variables were assessed using non-parametric Spearman’s correlation analyses. The Bonferroni method was used to correct for collinearity of multiple correlations. Specifically, the raw p-value was left unchanged and the overall type I error threshold was adjusted by comparing the raw p-values to 0.05/number of tests. A total of pair-wise correlation analyses were performed for PSR/R1f and the other MRI metrics, yielding a Bonferroni-corrected p-value ≤0.002 (e.g., 0.05/28). Here, we performed a pairwise analysis and looked at all possible combinations among all variables. When relating PSR/R1f to clinical measures, 9 correlation analyses were performed contrasting SIR-derived metrics (as a group) of each tissue type against each clinical variable, yielding a Bonferroni-corrected p-value ≤0.006 (e.g., 0.05/9).

Inter-scan repeatability was quantified by estimating differences in each measurement between scans and the 95% limits of agreement (LOA = mean of difference ± 1.96*SD of the differences).

Results

SIR-qMT was well tolerated and none of the subjects interrupted the scan prematurely. Inter-scan SIR-qMT repeatability data from patients and HCs are reported in Table 3. For all ROIs, the 95% LOA for PSR and R1f were [−2.7,3.0%] and [−0.07,0.07 s−1], respectively, suggesting that both PSR and R1f measurements can be used to detect subtle changes over time. In addition, no significant bias was detected for PSR (scan 1 = 10.4±4.2, scan 2 = 10.5±4.2%) or R1f (scan 1 = 0.79±0.17 −1, scan 2 = 0.80±16 s−1) across scans.

Table 3:

Test-rest reproducibility analysis of PSR and R1f

| Parameter | Tissue | Test Scan | Retest Scan | Difference | LOA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PSR (per-cent) | NWM | 12.5±2.6 | 12.5±2.7 | 0.0±0.6 | [−1.1, 1.1] |

| NAWM | 11.9±3.2 | 11.9±3.6 | 0.0±2.2 | [−4.3, 4.2] | |

| Lesions | 4.5±2.0 | 5.1±2.2 | 0.6±1.3 | [−2.1, 3.2] | |

| R1f (s-1) | NWM | 0.89±0.08 | 0.89±0.08 | 0.0±0.02 | [−0.04, 0.04] |

| NAWM | 0.84±0.11 | 0.84±0.11 | 0.00±0.04 | [−0.08, 0.08] | |

| Lesions | 0.55±0.11 | 0.58±0.10 | 0.03±0.05 | [−0.07, 0.12] |

Shown are the mean ± standard deviation parameter values across all normal white matter (NWM), normal appearing white matter (NAWM) and lesions for the test and retest scans, the resulting mean paired difference between scans, and the limits-of-agreement (LOA).

Inter-scan variability analyses were further broken down by tissue type (e.g., NWN, NAWM, and lesions) as we detail in Table 3. Estimated parameters were repeatable for all ROIs, although larger LOAs were observed for lesions and NAWM due to the smaller size of these regions.

Differences in SIR-qMT derived metrics

• BHs versus T2-lesions

This analysis was obtained in 209 BHs that were compared with contra-lateral T2–155 lesions identified from 9 patients (Fig. 3a and 3b). Both PSR (p<0.0001) and R1f (p<0.0001) values differed between cBHs compared to T2-lesions. A larger AIC was observed for PSR (505.9) compared to R1f (365.4)

Figure 3: PSR and R1f values of brain regions with different tissue composition.

Comparisons in PSR and R1f values measured in different tissue types. Fig.3a-b compares PSR (a) and R1f (b) between non-acute BHs (stripped bars) and T2-lesions (white bars). Fig.3c-d compares PSR (c) and R1f (d) between T2-lesions (stripped bars) and normal appearing white matter (NAWM, white bars). Fig.3e-f compares PSR (e) and R1f (f) between NAWM in patients (stripped bars) and normal WM (NWM) in healthy controls (white bars). The graphs display mean (bars) and standard deviations.

• T2-lesions versus NAWM

This analysis was obtained in 606 T2-lesions that were compared with contra-lateral NAWM ROIs from patients (Fig. 3c and 3d). Both PSR (p<0.0001) and R1f (p<0.0001) values differed between T2-lesions compared to NAWM. Comparable AIC values were observed for PSR (1324.2) and R1f (1396.7).

• NAWM versus NWM

This analysis was obtained in 136 NAWM ROIs that were compared to 72 NWM ROIs from 17 patients and 9 HCs (Fig. 3e and 3f). Neither PSR nor R1f differed between NAWM and NWM (p=0.9 and AIC=35.5 for both).

Histogram analyses (Fig. 4) inclusive of all NAWM and NWM voxels confirmed this trend. However, when only patients with EDSS>1 (n=7, representing patients with some degree of disability accumulation above non-symptomatic signs) were considered, significant reductions of PSR (p = 0.05) and R1f (p = 0.005) were observed in comparison to HCs.

Figure 4. Histogram analysis PSR.

(a) and R1f (b) NWM (black) and NAWM histograms of patients with Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS) score≤1 (red) and EDSS>1 (blue). The solid dark line represents the mean values and the shaded region the mean±standard error.

Correlations between SIR-qMT derived measures and other MRI metrics

Table 4 depicts all correlation analyses between clinical and MRI variables. Fig. 5 displays a subset of the relationships between SIR-qMT metrics and other MRI/clinical variables that persisted after Bonferroni corrections. Of note, SIR-qMT measures derived from T2-lesions explained the variance seen in clinical disability more than BHs; however, lesional SIR-qMT derived metrics correlated with BH lesion volume more than T2-lesion burden.

Table 4A:

Correlations between PSR/R1f and other MRI metrics

| NAWM | T2-lesions | BHs | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PSR | R1f | Volume | PSR | R1f | Volume | PSR | R1f | ||

| NAWM | PSR | 0.82 | −0.69 | 0.61 | 0.60 | −0.60 | 0.38 | 0.30 | |

| R1f | −0.60 | 0.51 | 0.58 | −0.59 | 0.34 | 0.34 | |||

| T2-lesions | Volume | −0.50 | −0.40 | 0.89 | −0.67 | −0.53 | |||

| PSR | 0.85 | −0.76 | 0.83 | 0.48 | |||||

| R1f | −0.73 | 0.64 | 0.61 | ||||||

| BHs | Volume | −0.83 | −0.59 | ||||||

| PSR | 0.54 | ||||||||

Figure 5: Correlations between imaging and clinical measures.

Plots depicting the most clinically relevant and statistically significant associations seen between clinical / MRI (T2-lesions and BHs volumes) variables and SIR-qMT metrics. One can note the presence of an outlier patient in fig. 5e. We present the output of the correlation obtained with (p- and r-values in black) and without (p- and r-values in gray) the presence of this outlier subject. From this analysis, it can be seen that similar correlations coefficients were obtained with and without the inclusion of this outlier patient, although the p-value of the association was smaller when the outlier outlier subject was excluded.

Discussion

We propose the first in vivo clinical translation of our optimized and histologically validated20 SIR-qMT protocol and demonstrate (i) the clinical feasibility of SIR-qMT at 3T and (ii) the ability of SIR-qMT derived metrics to predict radiological and clinical disease severity. We recognize that additional gains in scan efficiency may be required prior to widespread clinical adoption of the SIR-qMT technique described here. We predict that future optimization work will meet this goal. To this end, our group’s work is already proving that 3–4-fold reductions in scan times are feasible through optimized 3D readouts and SENSE acceleration in two directions, resulting in clinically feasible whole-brain acquisitions in less than ten minutes.31

Differences in PSR and R1f between lesional and non-lesional tissues

In this research, we demonstrate that SIR-qMT derived metrics are reproducible in MS patients and define the degree of disease severity, as measured by gold-standard imaging and clinical measures. Mindful of the well-known differences in myelin quantity between different anatomical brain regions, we performed an anatomically-specific analysis to determine pathological changes in PSR and R1f Following this approach, we observed that PSR and R1f differed between lesional and non-lesional tissue and between T2-lesions and BHs. These findings were expected based on of previous post mortem literature16 that showed strong correlations between PSR and myelin quantity, as measured by Luxol Fast Blue staining in an animal model system of type III oligodendrogliopathy. Schmierer and collaborators15 also demonstrated correlations between the fraction of macromolecular protons and Luxol Fast Blue staining in MS brains ex vivo. We validated SIR-qMT against histopathology in MS samples and showed the ability of PSR and R1f maps to identify and quantify both areas of demyelination (like clinical T2-weighted images)20 and remyelination, which go undetected using clinical methods.32

Comparisons between AIC showed that the magnitude of these changes was larger for PSR compared to R1f, only when BHs were compared to T2-lesions but not when T2 lesions were compared to NAWM ROIs. The findings provide indirect evidence of different sensitivity to pathologies between PSR and R1f. These two are complementary measures in that they are reflective of the percent (%) quantity of pool of free molecules not bound to macromolecules (PSR) and the rate of the free water signal longitudinal magnetization recovery (R1f, s−1). This rate is proportional to the quantity of bound macromolecules, although it is additionally sensitive to other factors (e.g., iron content). PSR is instead more specific to myelin only. Thus, the two measures may be interchangeable only when comparisons are obtained between areas with neglectable iron content, e.g., between chronic inactive lesions33 or between areas with intra-oligodendrocytes preserved iron, 218 e.g., NAWM and remyelinated lesions.

Interestingly, no differences were seen in both PSR and R1f between NAWM and NWM. We attributed this finding to the large variance seen in NAWM PSR and R1f values across patients. Indeed, when this variance was reduced by dividing patients into cohorts with minimal (or no) disability (EDSS<1) and those with accreted physical disability, a net separation was seen in PSR and R1f values between NAWM and NWM. We chose an EDSS cut-off of 1, since an EDSS=1 may represent impaired yet non-symptomatic (e.g., slight changes in deep tendon reflexes) patients.

It is also important to note that heterogeneity exists in the abnormal histopathological changes seen in the so-called NAWM. For instance, Allen34 and collaborators studied NAWM abnormalities in 54 MS samples. Of these, up to 28% had no pathological alterations in the NAWM. For the most part, samples for which injury was confirmed 230 showed signs of gliosis with only 13% displaying demyelination.

Correlations between PSR and R1f and other radiological and clinical metrics

Clinical MRI correlation analyses yielded several interesting results. Quality (as measured by SIR-qMT derived measures) and quantity (as measured by lesion volume) of disease were inter-related. Specifically, volume of BHs was associated with PSR measured in both T2-lesions and BH. The data are interesting and suggest that patients forming more BHs have an overall tendency to form (non BH) lesions with a larger degree demyelination and a less propensity to repair.

Disease duration was inversely associated with PSR and R1f measured in T2-lesions. This association was also seen with PSR measured in BHs though its significance was lost upon correcting for multiplicity. Overall the data suggests that the ability of MS patients to repair an injured tissue weakens over time. This phenomenon may be due to chronic demyelination and associated exhaustion of biological reparative strategies as MS progresses. In addition, aging which parallels disease duration may also play a role given its well-recognized detrimental effect on neuroprotection.35

PSR and R1f measures derived from T2-lesions correlated significantly with T25-FW (PSR) and with the EDSS score (R1f). We note that one of the patients had an extreme T25-FW value which contributed substantially to the correlation reported in fig. 5e. When this outlier value was removed, similar correlations coefficients were obtained. The p-value of this association was smaller and above the Bonferroni corrected threshold, yet <0.05.

These findings suggest that SIR-qMT holds promise as a sensitive marker of myelin injury and patient disability. These data, in conjunction with the demonstration of lower PSR and R1f in patients with EDSS scores >1, testify for the ability of SIR-qMT to measure changes in microstructural myelin integrity that reflects clinical disability. Lack of associations between clinical scores and SIR-qMT measures obtained in BHs, may be due to a ceiling effect, in that the range of variability in myelin content is narrower for these lesions, some of which may have little if any myelin left.

Study limitations and conclusions

Two main limitations of our work must be acknowledged. First, the patient cohort was relatively small and heterogeneous in terms of clinical features. These characteristics limited our ability to answer biological-clinical questions related to different MS phenotypes. Second, although we attempted to match the control and patient cohorts for sex and age, additional, larger-scale studies are required to fully assess the effect of these variables on the estimated SIR parameters within each cohort.

Assessing the ability of SIR-qMT to quantify tissue changes was the primary goal of this study. This assessment is the first important pre-requisite a given sequence must meet to be further applied on larger clinical scale. To this end, our data are encouraging and point toward the ability of SIR-qMT derived metrics to be promising biomarkers of neurodegeneration and repair in MS.

Table 4B:

Correlations between imaging and clinical measures

| Disease duration | EDSS | T25-WF | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NAWM | PSR | −0.45 | −0.33 | −0.57 |

| R1f | −0.39 | −0.23 | −0.42 | |

| T2-lesions | PSR | −0.74 | −0.57 | −0.63 |

| R1f | −0.71 | −0.63 | −0.44 | |

| BHs | PSR | −0.61 | −0.44 | −0.62 |

| R1f | −0.37 | −0.43 | −0.31 |

Dark Gray cells represent statistically significant correlations after Bonferroni correction (p≤0.006), while light gray cells indicate other potential trends (0.05≥p>0.006). Fig. 5c–f shows scatterplots for correlations with bold numbers. BHs = black holes; EDSS = Expanded Disability Status Scale; NAWM = normal appearing white matter; T25-FW = Timed 25-Foot Walk Test.

Acknowledgments

We thank all patients and HCs who participated in our study, all VUIIS MRI technicians for their assistance with scanning, Ms. Kehaunani Hubbard for assistance with scheduling and Nikita C. Thomas with image analysis.

Sources of support include: (FB): extramural program of the Clinical and Translational Science Awards (UL1TR000445–06 from National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences/NIH) and PP-1801–29686; (SAS): NMSS RG-1501–02840; (RD): NIH/NIBIB K25 EB013659 and NIH/NINDS R01 NS97821; (JZ): NIH/NCI K25 CA168936. Our manuscript’s contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent official views of the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences or the NIH.

Footnotes

None of the authors declare any conflicts of interest with this work.

References

- 1.Mahad DH, Trapp BD, Lassmann H. Pathological mechanisms in progressive multiple sclerosis. Lancet Neurol 2015; 14: 183–193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fox RJ, Thompson A, Baker D, et al. Setting a research agenda for progressive multiple sclerosis: the international collaborative on progressive MS. Mult Scler 2012; 18: 1534–1540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wolff SD, Balaban RS. Magnetization transfer contrast (MTC) and tissue water proton relaxation in vivo. Magn Reson Med 1989; 10: 135–144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Laule C, Vavasour IM, Kolind SH, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging of myelin. Neurotherapeutics 2007; 4: 460–484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Berry I, Barker GJ, Barkhof F, et al. A multicenter measurement of magnetization transfer ratio in normal white matter. J Magn Reson Imaging 1999; 9: 441–446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schmierer K, Scaravilli F, Altmann DR, et al. Magnetization transfer ratio and myelin in postmortem multiple sclerosis brain. Ann Neurol 2004; 56: 407–415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vavasour IM, Laule C, Li DK, Traboulsee AL, MacKay AL. Is the magnetization transfer ratio a marker for myelin in multiple sclerosis? J Magn Reson Imaging 2011; 33: 713–718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Moll NM, Rietsch AM, Thomas S, et al. Multiple sclerosis normal-appearing white matter: Pathology-imaging correlations. Ann Neurol 2011;70: 764–773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Blezer EL, Bauer J, Brok HP, Nicolay K, ‘t Hart BA. Quantitative MRI-pathology correlations of brain white matter lesions developing in a non-human primate model of multiple sclerosis. NMR Biomed 2007; 20: 90–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Odrobina EE, Lam TY, Pun T, Midha R and Stanisz GJ. MR properties of excised neural tissue following experimentally induced demyelination. NMR Biomed 2005; 18: 277–284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Henkelman RM, Huang X, Xiang QS, Stanisz GJ, Swanson SD, Bronskill MJ. Quantitative interpretation of magnetization transfer. Magn Reson Med 1993; 29: 759–766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sled JG, Pike GB. Quantitative interpretation of magnetization transfer in spoiled gradient echo MRI sequences. J Magn Reson 2000; 145: 24–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gochberg DF, Gore JC. Quantitative imaging of magnetization transfer using an 316 inversion recovery sequence. Magn Reson Med 2003; 49: 501–505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li K, Zu Z, Xu J, et al. Optimized inversion recovery sequences for quantitative T1 and magnetization transfer imaging. Magn Reson Med 2010; 64: 491–500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schmierer K, Tozer DJ, Scaravilli F, et al. Quantitative magnetization transfer 320 imaging in postmortem multiple sclerosis brain. J Magn Reson Imaging 2007; 26:4 1–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Janve VA, Zu Z, Yao SY, et al. The radial diffusivity and magnetization transfer pool size ratio are sensitive markers for demyelination in a rat model of type III multiple sclerosis (MS) lesions. Neuroimage 2013; 74 :298–305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yarnykh VL, Bowen JD, Samsonov A, et al. Fast whole-brain three-dimensional macromolecular proton fraction mapping in multiple sclerosis. Radiology 2015; 4: 210–220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dortch RD, Li K, Gochberg DF, et al. Quantitative magnetization transfer imaging of human brain at 3T via selective inversion recovery. Magn Reson Med 2011; 66: 1346–1352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dortch RD, Moore J, Li K, et al. Quantitative magnetization transfer imaging of human brain at 7T. Neuroimage 2013; 64: 640–649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bagnato F, Hametner S, Franco G, et al. Selective inversion recovery quantitative magnetization transfer brain MRI at 7T: clinical and post-mortem validation in multiple sclerosis. J Neuroimaging 2018; 4:380–388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Smith AK, Dortch RD, Dethrage LM, Smith SA. Rapid, high-resolution quantitative magnetization transfer MRI of the human spinal cord. Neuroimage 2014; 95: 106–116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dortch RD, Bagnato F, Gocherg DF, et al. Optimization of Selective Inversion Recovery Magnetization Transfer Imaging for Macromolecular Content Mapping in the Human Brain. Magn Reson Med 2018; 80: 1824–1835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fazekas F, Ropele S, Enziger C, Seifert T, Strasser-Fuchs S. Quantitative magnetization transfer imaging of pre-lesional white-matter changes in multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler 2002; 8: 479–484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lublin FD, Reingold SC, Cohen JA, et al. Defining the clinical course of multiple sclerosis. Neurology 2014; 83: 278–286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Thompson AJ, Banwell BL, Barkhof F, et al. Diagnosis of multiple sclerosis: 2017 revision of the McDonald criteria. Lancet Neurol 2018; 17: 163–173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kurtzke JF. Rating neurologic impairment in multiple sclerosis: an expanded disability status scale (EDSS). Neurology 1983; 33: 1444–1452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cutter GR, Baier ML, Rudick RA, et al. Development of a multiple sclerosis 351 functional composite as a clinical trial outcome measure. Brain 1999; 122: 871–882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fazekas F, Barkhof F, Filippi M. Unenhanced and enhanced magnetic resonance imaging in the diagnosis of multiple sclerosis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1998; 64 354 Suppl 1:S2–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bagnato F, Jeffries N, Richert ND, et al. Evolution of T1 black holes in patients with multiple sclerosis imaged monthly for four years. Brain 2003; 126: 1782–789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhang YY, Brady M, Smith S. Segmentation of brain MR images through a hidden Markov random field model and the expectation-maximization algorithm. IEEE Transactions on Medical Imaging 2001; 20: 45–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cronin MJ, Zhu J, Gochberg D, Dortch R. Optimization and acceleration of selective inversion recovery imaging for practical whole-brain quantitative magnetization transfer measurements. ISMRM 2018: Paris, France: abstract 2229. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bagnato F, Hametner S, Pennell D, et al. 7T MRI-Histologic Correlation Study of Low Specific Absorption Rate T2-Weighted GRASE Sequences in the Detection of White Matter Involvement in Multiple Sclerosis. J Neuroimaging 2015; 25: 370–378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bagnato F, Hametner S, Boyd E, et al. Untangling the R2* contrast in multiple sclerosis: a combined MRI-histology study at 7.0 Tesla. PLoS One 2018; 13:e0193839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Allen IV, McQuaid S, Mirakkur M, et al. Pathological abnormalities in the normal appearing white matter in multiple sclerosis. Neurol Sci 2001; 22: 141–144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Trojano M, Liguori G, Bosco G, et al. Age-related disability in multiple sclerosis. Ann Neurol 2002; 51: 475–480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]