Abstract

Beyond demonstrated effectiveness, research needs to identify how peer support can be implemented in real-world settings. Telephone peer support offers one approach to this. The purpose of this study is to evaluate telephone peer support provided by trained peer staff for high-risk groups, implemented according to key tasks or functions of the Reciprocal Peer Support model (RPS) providing both standardization and adaptability. The methods used in the study include the review of contact data for years 2015–2016 from telephone peer support services of Rutgers Health University Behavioral Health Care, serving veterans, police, mothers of children with special needs, and child protection workers; structured interviews with peer supporters and clients; and audit of case notes. Across 2015–2016, peer supporters made 64,786 contacts with a total of 5,616 callers. Adaptability was apparent in 22% of callers’ relationships lasting ≤1 month and 43% ≥1 year, voicemails valued as communicating presence, 92% of callers receiving support with psychosocial issues, 65% with concrete problems, such as medical or other services, 88% receiving social support, and 88% either resolving an issue (e.g., finding employment) or making documented progress (e.g., getting professional treatment, insurance, or children’s services). With the balance of standardization and adaptability provided by the RPS, telephone peer support can address diverse needs and provide diverse contact patterns, assistance, support, and benefits.

Keywords: Peer support, Standardization, Telephone, Stress, Mental health, High risk

Implications.

Practice: The utilization of a structured model of peer support, in this case, the Reciprocal Peer Support Model, and strong IT support, can provide a base from which trained peer supporters are able to adapt their services to address diverse client needs and preferences.

Policy: Peer support delivered by telephone and offered with the option of anonymity is a promising strategy for reaching groups who, due to substantial stressors, may be at risk for mental health problems and may not utilize conventional services.

Research: The use of multiple data sources, in this case, objective contact data, detailed records of contacts, and semistructured interviews with clients and peer staff, assist in a detailed general evaluation of a complex program delivered in a real-world setting and allow for the estimation of benefits of that program.

Introduction

Peer support provided by “community health workers,” “lay health advisors,” “promotores de salud,” and individuals with a number of other titles have been shown to play influential roles in health and health care [1–3]. Beyond demonstrations of effectiveness, however, research is needed to identify ways in which peer support can be implemented and disseminated through real-world health systems and community services. One approach is peer support delivered via telephone [4–6].

Given the broad evidence for its effectiveness [1–3,7,8], a major challenge is disseminating peer support and, in so doing, balancing standardization with adaptability or flexibility. Its person-centered quality, responsiveness to needs and objectives identified by the recipient, and providing the opportunity to talk with someone who has “walked in my shoes” [9–11] may be difficult to achieve through fixed protocols. Through Peers for Progress and the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Diabetes Initiative [12–14], we have pursued adaptability by standardizing around functions rather than specific content or protocol [15,16]. Functions are the needs and immediate objectives that services address. For example, key functions of diabetes self-management may include individualized assessment, collaborative goal setting, problem-solving skills, access to resources (such as for buying healthy food), and continuity of quality clinical care [13,14]. This standardization by function leaves individual programs free to decide how functions may best be adapted to their populations and settings.

To balance standardization and adaptability, the Rutgers University Behavioral Health Care’s (RUBHC) peer support telephone services utilize a model of Reciprocal Peer Support (RPS) [17] developed with knowledge accumulated from more than a decade providing peer support services and in accordance with best practices for peer support programs identified in a white paper of the Department of Defense Centers for Excellence [18]. The RPS model centers on four key functions or tasks: (a) connection and pure presence, (b) information gathering and risk assessment, (c) case management and goal setting, and (d) resilience, affirmation, praise, and advocacy. Training and protocols are organized around these and then followed in a flexible manner, for example, emphasizing connection and pure presence—developing rapport and trust—before proceeding with detailed information gathering and risk assessment. Case management and goal setting are then individualized based on that information and assessment. With the support of high-quality information technology (IT), program monitoring and prompts are also organized around the four tasks.

To assess this approach to guiding dissemination with standardization, as well as adaptability, and to assess the channel of telephone peer support for reaching high-priority/high-risk groups, the present paper examined RUBHC peer support telephone services in terms of (a) the characteristics of peer support provided, including patterns of use, (b) benefits observed through a sample of callers, and (c) key features, success factors, and challenges reported in structured interviews with peer supporters and their clients.

Methods

Evaluation included contact data for years 2015–2016 from telephone peer support services of RUBHC, along with audit of case notes to characterize the support provided and its benefits, and semistructured interviews with callers and peer supporters.

Setting

RUBHC provides peer support telephone services to high-risk groups, including law enforcement officers (Cop2Cop), veterans (Vet2Vet), child protection workers (Worker2Worker), caregivers of those with dementia (Care2Caregivers), and mothers of children with special needs (Mom2Mom). Emphasizing cultural tailoring, as opposed to matching by problems or clinical concerns, peer supporters are members of the groups they serve, for example, retired police answer calls from police callers, retired social workers from current child protection workers, and so on.

Eight day training covers skills and topics central to Reciprocal Peer Support model [17], including rapport building and communication skills, cultural competence relating to the subcultures served in the program, behavioral health training and recovery principles, managing crises and emergent situations, self-care, and ongoing support. Peer supporters also receive training from their supervisors for the groups they serve. The RPS curriculum is a composite drawn from national organizations, such as the American Association of Suicidology, International Critical Incident Stress Foundation, and Mental Health America, and broadly follows the peer support competencies outlined in a Department of Defense white paper [18].

Peer staff respond to incoming initial and recurring calls from clients, make outgoing calls on a scheduled basis, and leave voicemails for clients indicating their continued interest in how the client is doing. Callers initiate contact for a variety of reasons with subsequent calls initiated by peer supporters or callers. Call frequency, duration, and the overall length of the peer support relationship are determined by caller needs and preference.

Quantitative evaluation of caller and call data

From routine monitoring of services, 2 years of call data (2015–2016) were collected from four RUBHC telephone peer support programs (Cop2Cop, Mom2Mom, Vet2Vet, and Worker2Worker). Care2Caregivers uses different software to document interactions, so data from it were not included in these analyses. Each caller was given a unique identification number. Details regarding the caller, as well as what was discussed, were collected as the calls took place. Objective data, such as date and time of call and peer supporter fielding the call, were recorded for all contacts, including voicemails. Due to many callers’ concerns for confidentiality, demographic information was not routinely collected.

Descriptive statistics, frequencies of contacts, and patterns of contact were determined utilizing StataSE, version 14.2 (College Station, TX). To determine patterns of contact, only callers with first calls before January 1, 2016 were included, that is, with more than 1 year remaining in the 2015–2016 period from which data were drawn. This provided data for a full year for each caller in order to characterize patterns of peer support over time.

Audit of selected case notes

Peer supporters kept detailed case notes to facilitate continuity of care. To assess the types of services and their impacts, a sample of call records was systematically abstracted by two raters (N.B. and M.E.) and thematically analyzed. To focus on cases with appreciable needs, they were sampled from those initially rated as urgent or emergent. To ensure an adequate time period in the case notes, the cases were randomly chosen from among 195 cases with first calls within 2015 to provide at least a full year before the end of data extraction, December 31, 2016. To accommodate research staff resources, 15 cases from each of the four programs were randomly selected, yielding a total of 60 sets of case notes for audit.

From 20 of the 60 sets, raters identified themes and characteristics that were codable and developed a coding rubric that was also discussed and revised iteratively through research team meetings. The entire set of notes for each case was coded, requiring, for example, options for coding multiple codes within categories. After the rubric was finalized, the two raters independently read and coded all 60 cases in Atlas.ti, achieving satisfactory agreement (Cohen’s Kappa = 0.81). The raters met regularly to discuss and resolve uncertainties by consensus. Their final ratings are summarized in Tables 1 and 2.

Table 1.

Characteristics of peer support across 60 urgent or emergent cases representing Rutgers Telephone Peer Support Programs

| All programs (N = 60) | Cop2Cop (n = 15) | Mom2Mom (n = 15) | Vet2Vet (n = 15) | Worker2Worker (n = 15) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| Pattern of engagement (>1 code possible) | ||||||||||

| Single contact | 10 | 17 | 2 | 13 | 1 | 7 | 3 | 20 | 4 | 27 |

| Episodic with follow-up | 22 | 37 | 7 | 47 | 2 | 13 | 8 | 53 | 5 | 33 |

| Ongoing peer support | 28 | 47 | 6 | 40 | 12 | 80 | 4 | 27 | 6 | 40 |

| Crisis relief + other type listed above | 13 | 22 | 5 | 33 | 1 | 7 | 5 | 33 | 2 | 13 |

| Reason for call (>1 code possible) | ||||||||||

| At least one psychosocial issuea | 55 | 92 | 15 | 100 | 14 | 93 | 11 | 73 | 15 | 100 |

| At least one basic needs isssueb | 39 | 65 | 7 | 47 | 15 | 100 | 11 | 73 | 6 | 40 |

| More than one reason for call | 54 | 90 | 12 | 80 | 15 | 100 | 13 | 87 | 14 | 93 |

| Referrals (>1 code possible)c | ||||||||||

| At least one referral | 32 | 53 | 10 | 67 | 14 | 93 | 9 | 60 | 3 | 20 |

| More than one referral | 19 | 32 | 3 | 20 | 11 | 73 | 5 | 33 | 0 | 0 |

| Social support (>1 code possible) | ||||||||||

| Provides connection/checks in | 43 | 72 | 8 | 53 | 14 | 93 | 9 | 60 | 12 | 80 |

| Provides social and emotional support | 43 | 72 | 9 | 60 | 13 | 87 | 11 | 73 | 10 | 67 |

| Problem solving | 18 | 30 | 0 | 0 | 12 | 80 | 3 | 20 | 3 | 20 |

| At least one type of social support | 53 | 88 | 13 | 87 | 15 | 100 | 13 | 87 | 12 | 80 |

| More than one type of social support | 35 | 58 | 4 | 27 | 13 | 87 | 8 | 53 | 10 | 67 |

| Caller activities/benefits (>1 code possible)d | ||||||||||

| Accessed referred services | 13 | 26 | 5 | 38 | 2 | 14 | 6 | 50 | 0 | 0 |

| Implements suggested solutions | 12 | 24 | 4 | 31 | 2 | 14 | 3 | 25 | 3 | 27 |

| Progress on issue | 41 | 82 | 10 | 77 | 13 | 93 | 11 | 92 | 7 | 64 |

| Resolved issue | 14 | 28 | 5 | 38 | 4 | 29 | 4 | 33 | 1 | 9 |

| At least 1 caller activity | 44 | 88 | 12 | 92 | 13 | 93 | 11 | 92 | 8 | 73 |

| More than 1 caller activity | 26 | 52 | 9 | 69 | 7 | 50 | 7 | 58 | 3 | 27 |

aPsychosocial issues include: interpersonal issues, mental health, substance use, workplace issues, and traumatic incidents.

bBasic needs issues include: connection to service, medical issues, housing issues, legal issues, transportation issues, financial issues, and employment issues.

cReferrals include: medical provider, mental health service, case worker, legal service, substance use service, financial service, employment assistance, housing assistance, and transportation assistance.

dCalculated only for cases that had more than one contact and, thus, caller activities and benefits were able to be assessed (n = 50).

Table 2.

Codes used in characterizing case notes and examples from case notes written by peer staff regarding 60 urgent or emergent cases representing Rutgers Telephone Peer Support Programs

| Code | Examples |

|---|---|

| Pattern of engagement | Single contact: peer support relationship is characterized by a single call between peer and participant. Episodic with follow-up: peer support relationship is characterized by the peer following up to engage the participant but with limited contact, apart from few brief and nonsubstantive phone calls. Ongoing support: relationship is characterized by a series of substantive interactions between participant and peer. Crisis relief plus one of above: participant calls about a traumatic event (i.e., death, officer-involved shooting, and motor vehicle accident) plus one of above, single, episodic, or ongoing contacts. |

| Reason for call—psychosocial issue | Officer called and needed to talk and seeking resources … he has had long time problems with anxiety and depression but called C2C [Cop2Cop] because of a panic attack. Reached out to Mom2Mom because her 15 y/o son … (with ASD [Autism Spectrum Disorder]) was extremely agitated and violent. [Client] called for peer support because is being experiencing anxiety and other adverse physical problems due to the severe stress from the job. |

| Reason for call—basic needs issue | Client called stating that he has a brain tumor caused by the drinking water on CLNC [Camp Lejeune, North Carolina] while he was in the Marine Corps from 78 to 85. Client stated that he was just looking for some help to repair his roof. Client called stating that he needs help with utility bills. Client stated that he has a shut off notice and Catholic Charities cannot help him. |

| Referrals | Gave caller info for HUD VASH (Housing & Urban Development Veterans Affairs Supportive Housing) as well as the number for the VA [Veteran’s Administration] veteran homelessness prevention line. [Peer staff] called [client] to provide a listing of psychologist part of the providers listing under Horizon Blue Cross & Blue Shield found online. |

| Provides connection/checks in | We discussed her recent vacation to Wildwood, and how she was planning to spend the upcoming weekend… I will call her next month to touch base, and she is aware that she may call if needed. She is feeling like she needs to open up more to people who can help her—she has been trying to be “supermom.”… She thanked me for calling and would like to speak again after her appointments the next three weeks. |

| Provides social and emotional support | [Peer staff} normalized feelings of anomie at different stages of police career, particularly in the smaller departments. Also pointed out that 9 days of 12 hr midnights could cause deleterious reactions. Also told him to monitor ETOH [alcohol]. We talked about just taking things one step at a time to prevent her from becoming overwhelmed. I praised her for her courage about taking time to further discuss feelings with supervisor to address her concerns and suggested not to allow this issue to create further problems. |

| Problem solving | She talked about some experiences she has been having with her husband. This writer talked about different strategies she could try when engaging her husband. She was also given the number to the Combat Call Center. [Client] called me today saying that she wanted to ask me questions about taking time off… I pointed out that comp time is subject to approval by supervision, so if her supervisor approves her request it wont be a problem. |

| Accessed referred services | [Client] called to update me that she had been in contact with the two advocates I recommended [advocate names] and spoke with [advocate], who upon hearing she was in Chatham, advised her to get an attorney, and recommended one. Spoke to Lt, [lieutenant] He was grateful for our assistance and the officer was sent to Florida to a “facility” who sent an affirmation to the department that he would be in residential Tx [treatment] for 30 to 90 days. |

| Implements suggested solutions | [Client] plans to take ten days off later this month and go to a mountain resort where there is no cell phone service. She also will take a week off in August [as discussed in prior conversation] She got an education attorney from Legal Aide… already spoke to her and has an appt. [as discussed in prior conversation] |

| Progress on issue | Client stated he was getting better. His first visit with the psychiatrist went well. The medication is helping. He likes him as a person. He will be seeing a therapist to talk about his concerns. She was happy because received a call that her welfare grant was approved and she should start getting benefits by next week… She also completed the intake for her siblings’ therapy and they will be involved in individual therapy weekly and family therapy at home once a month. [Client] has made a decision to begin actively make moves to get out of current job situation. |

| Resolved issue | She and her husband did file for due process, after retaining an attorney and it only took one meeting with the Superintendent to have him grant their request for a new classroom setting for [name]. He is so much better and happier in school now. She told me that she gave her 2 weeks notice that she is quitting… She said that she plans to attend cosmetology school, that it’s a 9-week course and that she will work part time as a home health aide for income. This writer called [client] who has been offered a position with the Department of Corrections. |

All examples are taken verbatim from case notes written by peer staff except pieces of text denoted by […]. Examples were chosen that illustrated the identified code; however, more than one code could be applied to each piece of text.

Semistructured interviews with peer supporters and callers

Semistructured in-depth telephone interviews included peer supporters and callers from the four programs that provided contact data and case notes (Cop2Cop, Mom2Mom, Vet2Vet, and Worker2Worker) plus Care2Caregivers for those caring for individuals with dementia. Interviews were completed with 10 peer support workers (2 from each program) and 12 callers (3 from each of Cop2Cop and Worker2Worker and 2 from each of the other three). Potential interviewees were chosen randomly from the pool of callers and peer staff who received or provided support between January 1, 2015 and December 31, 2016. Interviews were completed between November 15, 2017 and February 9, 2018 with those who responded affirmatively to interview requests. Due to the sensitive nature of the interviews and the interviewees’ desire to remain anonymous, demographic data were not collected. The interviewer (M.E.) was a doctoral research assistant at the University of North Carolina paid by subcontract from RUHBHC for the purpose of the evaluation. She had previous contact with some of the peer staff through several project meetings but had no supervisory relationship with them and had no contact with callers other than through the present interviews. The interview guide for peer supporters included descriptions of the training received, specifics about the support they provide, their workflow, and thoughts on how services could be improved. For callers, interviews focused on expectations of peer support prior to engaging with the programs, specifics about the support received, benefits or drawbacks to participation, and how services could be improved. Interviews were audio recorded, transcribed, and independently thematically analyzed utilizing Atlas.ti by two coders (M.E. and P.Y.T.) following standard procedures [19], including inductive identification of themes and frequent meetings to resolve coding discrepancies.

Results

Engagement

Over 2 years (January 1, 2015–December 31, 2016), the four programs accounted for a total of 64,786 contacts, including calls and voicemails, to a total of 5,616 callers. Forty-nine percent of these contacts were phone calls and the remaining 51% voicemails. Disaggregated by program, Cop2Cop accounted for 24% of these contacts (15,494 contacts with 1,132 callers), Mom2Mom—42% (27,227 contacts with 2,088 callers), Vet2Vet—23% (14,883 contacts with 1,436 callers), and Worker2Worker—11% (7,182 contacts with 960 callers). Each caller received a mean of 11.5 total contacts, split evenly between calls (5.8) and voicemails (5.8). Across programs, mean number of calls ranged from 3.1 in Worker2Worker to 6.4 in Vet2Vet.

Patterns of contact within and across programs

Contact data are organized with reference to the first year over which individual callers received services with counts of calls received in the first month, second month, and so on through 1 year. For an individual whose first call was on January 1, 2015, all calls between January 1 and January 31, 2015 would be entered as occurring in Month 1, whereas, for an individual entering November 15, 2015, all calls between November 15 and December 14, 2015 would be entered as occurring in Month 1. Only callers with first calls before January 1, 2016 were included to allow a full year of data collection to characterize accurately the pattern of peer support contacts over time. The resulting sample size was 26,033 phone calls with 3,487 callers.

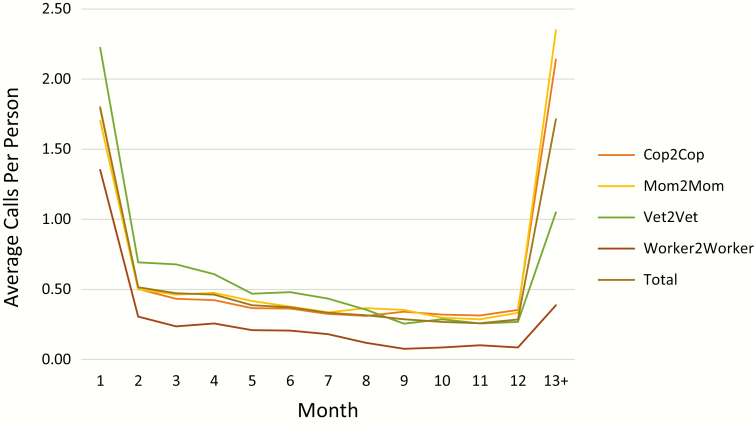

For all callers and disaggregated by each of the four programs, Fig. 1 presents the average number of calls per person per month for the first 12 months and beyond 12 months following individuals’ entrances. Across programs, Cop2Cop had 736 callers with a total of 5,886 calls and an average of 8.1 phone calls per caller; Mom2Mom—1,429 callers with a total of 11,807 calls and an average of 8.3 phone calls per caller; Vet2Vet—802 callers with a total of 6,465 calls and an average of 8.1 phone calls per caller; and Worker2Worker—520 callers with a total of 1,875 calls and an average of 3.7 phone calls per caller.

Fig 1.

Average calls per person per month following entry into program, total across programs, and disaggregated by program.

Although the average number of calls varied across programs, their pattern was remarkably consistent. Across all four programs, an average of 24% of calls occurred in the first month, ranging from 21% for Mom2Mom to 37% for Worker2Worker. After that first month, the number of calls within each month declined steeply but remained fairly constant, from 7% and 6% in Months 2 and 3 to 3% and 4% in Months 11 and 12. Aggregating across programs and by quarter, 37% occurred within Months 1–3, 16% within Months 4−6, 13% within Months 7–9, 11% within Months 10–12, and 23% after Month 12. The one apparent exception to this pattern was the number of calls after 12 months for Mom2Mom, totaling 3,356 (28%) of the total of 11,807 calls within the 2 year period audited. Presumably, this reflected the enduring nature of challenges in raising children with special needs.

Across individuals, the length of time over which contacts took place varied widely, with 22% of callers’ contacts bridging 1 month or less and 43% extending over 1 year. This varied by program—21% 1 month or less for Cop2Cop, 15% for Mom2Mom, 32% for Vet2Vet, and 26% for Worker2Worker. Percentages lasting over a year were 52% for Cop2Cop, 57% for Mom2Mom, 27% for Vet2Vet, and 17% for Worker2Worker.

Audit of case notes regarding ways peer support is used and is helpful

Gender varied widely across the 60 audited cases, with females comprising 100% in Mom2Mom and Worker2Worker but 33% in Vet2Vet and 20% in Cop2Cop. Fifty-two percent were employed although this too varied greatly, from 20% in Mom2Mom to 100% in Worker2Worker. Mentioning an existing chronic disease were 47% in Mom2Mom, 27% in Worker2Worker, 20% in Vet2Vet, and none in Cop2Cop. Table 1 details the characteristics of the peer support provided and Table 2 provides examples of the codes used in this characterization.

What problems are addressed?

Across audited cases, 92% were coded as receiving support with psychosocial issues, including mental health problems (e.g., depression and anxiety disorder) but also workplace and interpersonal conflicts or stressors. This ranged from 73% in Vet2Vet to 100% in Cop2Cop and Worker2Worker. Reflecting the grounded nature of peer support and the RPS model’s emphasis on individuals’ concrete problems [20–23], 65% received help with basic needs, including medical services (37%) or connections with other types of services (35%). This varied across the several programs so that 100% of the cases from Mom2Mom received help with a basic need.

Referrals

As detailed in Table 1, cases could be coded as receiving multiple types of services, reasons for calls, and so forth. Types of referrals varied and included: medical providers, mental health services, case workers, legal services, substance use services, financial services, employment assistance, housing assistance, and transportation assistance. Fifty-three percent of callers received at least one referral. Referrals to mental health providers (28%) and case workers (28%) were most common, followed by medical and legal services, 17% each. Again, variation among the programs was substantial: 87% in Mom2Mom were referred to case workers, while, in Cop2Cop, 47% were referred to mental health and 20% to substance use services.

Social support

Reflecting the varied nature of social support, individuals received social and emotional support in addition to the concrete assistance and referrals noted above [17,24–26,27]. Thus, 88% of cases received some kind of social support, including simple connection or check-in (72%), social or emotional support (72%), or assistance in problem solving (30%), with over half, 58%, being coded as receiving more than one type. Given the simple value of being there [20] (F. B. Fisher, P. Y. Tang, M. Evans, et al., Unpublished data) or “pure presence” in the RPS model [17], the importance of simple patterns of connection and check-ins documented in 72% of cases is noteworthy. At the same time, more elaborated social and emotional support was identified in 87% of cases in Mom2Mom but also 60% in Cop2Cop, questioning U.S. cultural stereotypes of independence and autonomy [28,29].

Benefits

Because benefits could only be assessed across several contacts, these were coded only for those who had more than one documented call (n = 50). Of these, 82% were coded as including documented progress in addressing a problem that was a focus of peer support. This ranged widely, including, for example, attending counseling or mental health treatment, obtaining medical insurance or needed services for a child, and taking time off to prevent job burnout. The majority of cases in each program exhibited progress: 77% in Cop2Cop; 93% in Mom2Mom; 92% in Vet2Vet; and 64% in Worker2Worker. In addition, 28% of the 50 were coded as having resolved an issue, for example, finding housing or employment or resolving a legal issue. Combining these, 88% were coded as either having resolved and/or made progress on an issue.

Themes of semistructured interviews with callers and peer supporters

Key features of engagement

Individuals called because they needed immediate help and usually had a preidentified problem and desired concrete advice and direction. They hoped to talk with someone who would be objective and experienced and often wished to remain anonymous. Peer supporters reported that the time for them to establish rapport with a new caller ranges from one to four phone calls.

Peer supporters identified three common patterns of contact. One reflects an urgent need for specific help with a problem. Nevertheless, callers may resist professional treatment, so the peer supporter may need to address resistance and then facilitate referral. In a second pattern, callers need time to talk, including about concerns related to both behavioral health problems and issues specific to the organizational cultures of the several groups. In a third pattern, individuals want routine phone calls to maintain contact. This may take the form of ongoing support for those who have dealt with a problem or have enduring issues such as those related to parenting a child with special needs or providing care for a loved one with dementia.

Value of integrated program

The peer support programs are comprehensive in their training, regular supervision, and continuing education. They also include “peer clinicians,” members of groups served who also have professional training, such as a retired police officer who is a licensed professional counselor. Peer supporters reported that being part of such a comprehensive program helped callers feel both the ability to connect with someone “like me,” as well as the security of knowing that sound professional services are also available through the peer. Supporters also indicated that this allowed them to provide support with confidence, knowing backup is available if needed, both at the moment when faced with a situation about which the peer supporter is unsure and as part of routine supervision.

Peer supporters identified additional specific factors that enhance their value:

-

•

Being “trained to listen” [Care2Caregivers Peer2] as a key part of providing support to callers and offering a safe space for the unfiltered expression of negative emotions.

-

•

Helping callers to problem-solve, offering suggestions but not judgment.

-

•

Being able to provide same-day referrals that often enhances the caller’s sense that the peer supporter cares about their well-being.

-

•

Providing encouragement and affirmation that callers are doing the best they can and that also conveys acceptance and promotes resilience.

Presence

Presence, or “just being there”, was identified as a fundamental characteristic of support, exemplified by the availability of peer support around the clock communicating security and help if one needs it, “just knowing there is someone out there that (sic) cares” [Vet2Vet Caller1].

Presence was demonstrated in a variety of ways. Calls are nearly always answered by a live person, not an answering system. At the same time, emotionally reassuring continuity of care is supported by IT systems that provide access to detailed notes of previous conversations so that the individual answering the phone can pick up where the primary peer supporter left off.

Following up after the initial phone call may be viewed by program managers and peer supporters as mere due diligence. Callers, however, took notice, reporting surprise when their peer supporter called to follow up counter to their experience with other providers. Reflecting perceived commitment of the peer supporter, one caller stated “I do not think she’s ever going to give up on me. She always checks up on me” [Mom2Mom Caller1].

Voicemails also were noted as a powerful way to connect with callers. The simple act of leaving a voicemail does not go unnoticed. Rather than not wanting to talk, callers described their engagement with their peer supporter as highly determined by their chaotic schedules and noted that when they were not able to answer the phone, “it wasn’t for lack of interest, it was the whirlwind thing” [Care2Caregivers Caller1]. Peer supporters indicated that they understood this, one describing continuing to follow up with a particular caller because, “she really cannot get to the phone, but when she gets to the phone she’s really grateful for that phone call, so I make note of never closing her case because I know she really enjoys getting my voicemails and when she is able to pick up she really enjoys being able to talk to me” [Mom2Mom Peer2]. Because of the importance of voicemails, RUBHC provides guidance and model “scripts” so that voicemails are perceived as personal messages rather than just a “call-me-back” or “automated or customer service” message. Peer supporters also sent emails and cards to maintain presence and provide reminders that support is available should it be needed.

Cultural tailoring

The program names, for example, “Cop 2 Cop” and “Mom 2 Mom,” make clear that callers will speak to someone with whom they share identity, concerns, and recognition that those in their group have particular needs or challenges, enhancing the potential for trust in the service. Several respondents noted that “a lot of veterans do not talk about a lot of things to non-veterans. We’re veterans, we’ve been there” [Vet2Vet Peer1] and, as one mother explained her trust in the service, “she has a special needs kid also, so she will think what I think” [Mom2Mom Caller2].

Benefits of peer support

In addition to referrals for mental health services or assistance with basic needs, callers reported reduced feelings of isolation and loneliness along with stress relief, peace, energy, and joy. Some noted a sense of clarity and reassurance, feeling as though they were “oxygenated again” [Care2Caregivers Caller1]. The normalization of callers’ experiences, “making the abnormal normal” [Care2Caregivers Caller1], was also identified as a positive effect.

Callers distinguished their experiences with peer support from those with traditional medical and mental health providers. Not viewed as “a sterile provider” [Care2Caregivers Caller1], distinguishing advantages of peer support include the ability to connect on a personal level and receive practical advice from someone with shared experience. Callers also noted peer supporters providing unconditional support with no judgment or pressure attached. They described their peer supporters as being real, understanding, compassionate, and good listeners.

Discussion

Telephone-based peer support organized around the RPS model [17] that provides both standardized tasks and adaptation to individuals may engage, provide diverse support, and encourage diverse beneficial changes among high-risk groups. Here, those groups included police, veterans, child protection workers, mothers of children with special needs, and those providing care to adults with dementia. This is an important model for extending peer support to those who may benefit from it. Further, the diversity of groups served attests to the robustness of the RPS model in providing a structure of standardization that also supports adaptability to different groups and their needs.

The use of several data sources allowed for a varied evaluation of RUBHC telephone peer support program. Over a 2 year period, the programs provided an average of 11.5 contacts to a total of 5,616 individuals facing frequent stressors placing them at high risk for psychological distress and mental health problems. Time over which contacts were sustained ranged from single contacts in 15% of cases to as long as 23 months, an underestimate given that the present audit of cases extended over only 2 years.

Auditing a selected sample of peer supporter case notes allowed for the detailed characterization of services provided and benefits. Eighty-eight percent of cases reviewed received some kind of social support, including problem solving, simple connection or check-in, or general social and emotional support. Although 92% received help with some kind of psychosocial issue, 65% also received help with basic needs, including connections to social, medical, financial, or housing services. Similar diversity of problems was reported in prior research on recipients of telephone counseling provided by mental health professionals [30].

As other studies have also shown [2,31], peer support was related to a wide range of benefits with 82% making some progress with one of the problems they faced (64%–93% across programs). Type of progress ranged widely, from accessing professional counseling to obtaining insurance or needed services for a child to taking time off to address job burnout. With 28% resolving a problem (e.g., finding a job), a total of 88% either resolved or made progress on a problem during the period for which case notes were audited. Similarly, in a study of telephone counseling provided by mental health professionals, over 80% reported improvement in the problems for which they had sought counseling [30]. The present research adds to this apparent benefits through telephone support provided by peers.

The adaptability of the RPS model is reflected in a striking theme of these findings, their diversity. The varied caller needs, patterns of contact, types of support, and types of benefits all point to the adaptability of the four RPS tasks. Connection and pure presence, information gathering and risk assessment, case management and goal setting, and resilience, affirmation, and praise [17] provide a standardized structure from which peer supporters then tailor assistance to individuals. The several patterns of contact, as well as the variety of topics addressed and types of progress documented, reflect the RPS emphasis on individualizing the assistance provided.

Rather than trading off one versus the other, standardization and adaptability may be complementary. For example, IT services enhance the structure of the RPS tasks by providing prompts to their use and by monitoring their application. At the same time, they encourage adaptability by providing not fixed scripts but talking points and resources that peer supporters can draw upon to address specific caller needs as they emerge. IT also supports adaptability as in the ability of the peer supporter “on call” to respond with quick reference to previous calls and concerns while answering a call at 2 am from someone with whom they may never have talked.

Connection and pure presence—“Being There” – can take many forms. Most striking, perhaps, is the role of voicemail. Rather than failures to connect, voicemails appear to be important ways in which peer supporters and callers can communicate continuing concern and availability, features of social support that may be as important as its actual delivery [32]. This value of voicemail was dramatically stated by a caller in Vets4Warriors, an RUBHC program for active-duty military, “I have listened to every one of the voicemails you left for me. You are the only one who continued to reach out. Because of you there is one less dead Marine.”

The impacts of stressors and stress on health are well documented [33–35]. Indeed, all of the groups served by these programs can be seen as vulnerable to the high demand/low control pattern that has been especially linked to physical illness [36,37]. Moreover, studies of several of the groups served to identify disproportionate health risks, for example, 33% of police officers reporting less than 6 hr sleep and 27% having metabolic syndrome (hypertension, high cholesterol or lipids, elevated blood glucose, or diabetes), in contrast to 8% and 19% of the general adult population, respectively [38]. Underscoring the influences of stressors on physical health and social concerns and the central importance of support from an accepting, available peer with whom to discuss concerns, the British Government appointed a cabinet minister for loneliness in 2018 [39]. Clearly the peer support services described here have an important role in behavioral medicine and physical health, as well as their roles in mental health and prevention.

Limitations

Four major limitations include the absence of controls for the present observations. Quasi-experimental comparisons across different groups that are or are not offered services could offer control. Participants could also serve as their own controls if programs gained information from them or cooperating agencies from before access to peer support. A second limitation is the evaluation of engagement, patterns in which individuals accessed services but not reach. Without good data on the numbers eligible, it is not possible to estimate the percentage who actually took advantage of programs.

The third major limitation is the absence of objective measures of impact. The diversity of benefits documented in the audited case notes make clear the challenge of quantifying those benefits, but appropriate standardized measures administered at caller entry and then regular intervals would provide useful information. So too might forms for callers to report progress or benefits, thereby capturing the variety of benefits that the current data signal as important.

A fourth limitation is the reliance on a single set of programs based in a single setting, RUBHC. Generalization to other telephone peer support programs should be with caution. Furthermore, the interviewees may not be representative of the entire population of RUBHC peer support staff and callers. For example, the callers that were interviewed may have been more engaged in help-seeking than the typical caller, perhaps biasing their views on the support provided relative to the general population who received peer support.

These evaluations were completed through a subcontract to Peers for Progress at the University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill, as part of a grant from the HealthCare Foundation of New Jersey to RUBHC for the purpose of characterizing the problems addressed, patterns of use, and types of services and benefits. To minimize bias in favor of the services, RUBHC staff had no direct role in data analysis, structured interviews, or coding and characterization of results, and UNC research staff reviewed results and presentations of findings for accuracy and fairness. As indicated by their coauthorship of this paper, however, RUBHC staff contributed to planning the evaluation and revising this report with respect to clarification and description of the services they provide.

Funding

This project was supported by a grant from the Healthcare Foundation of New Jersey to Rutgers University Behavioral Health Care, Department of Psychiatry, Rutgers University Medical School. This project was also supported from the University of North Carolina –Michigan Peer Support Core of the Michigan Center for Diabetes Translational Research (P30 DK092926, William Herman, PI).

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflicts of Interest: C.C. is the Peer Support Director of the Rutgers University Behavioral Healthcare National Call Center and D.D.V. is the program coordinator for the Mom2Mom and Worker2Worker programs of the Center that are among those evaluated in this paper. No other authors have any pertinent conflicts of interests.

Authors’ Contributions: M.E., P.Y.T., N.B., E.B.F., D.D.V., and C.C. conceived and planned the evaluation of services presented. M.E. conducted the semi-structured interviews. M.E. and P.Y.T. analyzed the interview data. N.B. analyzed the quantitative call data. M.E. and N.B. analyzed the case note data. M.E., P.Y.T., N.B., and E.B.F. drafted the interpretation of results. E.B.F. and M.E. took the lead in writing the manuscript. All authors reviewed and provided critical feedback on the manuscript and approved its final form.

Ethical Approval: All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. The protocol was approved by the Rutgers New Brunswick Health Sciences Institutional Review Board for the Protection of Human Subjects.

Informed Consent: For this type of retrospective study, formal consent is not required..

References

- 1. Viswanathan M, Kraschnewski JL, Nishikawa B, et al. Outcomes and costs of community health worker interventions: A systematic review. Med Care. 2010;48(9):792–808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Perry HB, Zulliger R, Rogers MM. Community health workers in low-, middle-, and high-income countries: An overview of their history, recent evolution, and current effectiveness. Annu Rev Public Health. 2014;35(1):399–421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Swarbrick M, Tunner TP, Miller DW, Werner P, Tiegreen WW. Promoting health and wellness through peer-delivered services: Three innovative state examples. Psychiatr Rehabil J. 2016;39(3):204–210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Dennis SM, Harris M, Lloyd J, Powell Davies G, Faruqi N, Zwar N. Do people with existing chronic conditions benefit from telephone coaching? A rapid review. Aust Health Rev. 2013;37(3):381–388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Small N, Blickem C, Blakeman T, Panagioti M, Chew-Graham CA, Bower P. Telephone based self-management support by “lay health workers” and “peer support workers” to prevent and manage vascular diseases: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Health Serv Res. 2013;13(1):533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Waller A, Dilworth S, Mansfield E, Sanson-Fisher R. Computer and telephone delivered interventions to support caregivers of people with dementia: A systematic review of research output and quality. BMC Geriatr. 2017;17(1):265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Swider SM. Outcome effectiveness of community health workers: An integrative literature review. Public Health Nurs. 2002;19(1):11–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Gibbons MC, Tyus NC. Systematic review of U.S.-based randomized controlled trials using community health workers. Prog Community Health Partnersh. 2007;1(4):371–381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Rosenthal EL, Brownstein JN, Rush CH, et al. Community health workers: Part of the solution. Health Aff (Millwood). 2010;29(7):1338–1342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Brownson CA, Heisler M. The role of peer support in diabetes care and self-management. Patient. 2009;2(1):5–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Davis KL, O’Toole ML, Brownson CA, Llanos P, Fisher EB. Teaching how, not what: The contributions of community health workers to diabetes self-management. Diabetes Educ. 2007;33(suppl 6):208S–215S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Fisher EB, Brownson CA, O’Toole ML, Shetty G, Anwuri VV, Glasgow RE. Ecological approaches to self-management: The case of diabetes. Am J Public Health. 2005;95(9):1523–1535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Fisher EB, Brownson CA, O’Toole ML, Anwuri VV. Ongoing follow-up and support for chronic disease management in the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Diabetes Initiative. Diabetes Educ. 2007;33(S6):201S–207S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Fisher EB, Brownson CA, O’Toole ML, et al. The Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Diabetes Initiative: Demonstration projects emphasizing self-management. Diabetes Educ. 2007;33(1):83–84, 86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Aro AR, Smith J, Dekker J. Contextual evidence in clinical medicine and health promotion. Eur J Public Health. 2008;18(6):548–549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Hawe P, Shiell A, Riley T. Complex interventions: How “out of control” can a randomised controlled trial be? BMJ. 2004;328(7455):1561–1563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Castellano C. Reciprocal peer support (RPS): A decade of not so random acts of kindness. Int J Emerg Ment Health. 2012;14(2):105–110. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Money N, Moore M, Brown D, et al. 2011. Best practices identified for peer support programs Available at https://www.mhanational.org/sites/default/files/Best_Practices_Identified_for_Peer_Support_Programs_Jan_2011.pdf. Accessibility verified November 7, 2019.

- 19. Boyatzis RE. Transforming Qualitative Information: Thematic Analysis and Code Development. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Fisher EB, Bhushan N, Coufal MM. Peer support in prevention, chronic disease management, and well being. In Fisher EB, Cameron LD, Christensen AJ, Ehlert U, Guo Y, Oldenburg B., Snoek FJ, eds. Principles and Concepts of Behavioral Medicine: A Global Handbook. New York, NY: Springer;643–677. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Fisher EB, Coufal MM, Parada H, et al. Peer support in health care and prevention: Cultural, organizational, and dissemination issues. Annu Rev Public Health. 2014;35(1):363–383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Chowdhary N, Anand A, Dimidjian S, et al. The Healthy Activity Program lay counsellor delivered treatment for severe depression in India: Systematic development and randomised evaluation. Br J Psychiatry. 2016;208(4):381–388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Rahman A. Challenges and opportunities in developing a psychological intervention for perinatal depression in rural Pakistan—A multi-method study. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2007;10(5):211–219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Fisher EB, Ballesteros J, Bhushan N, et al. Key features of peer support in chronic disease prevention and management. Health Aff (Millwood). 2015;34(9):1523–1530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Fisher EB, Boothroyd RI, Coufal MM, et al. Peer support for self-management of diabetes improved outcomes in international settings. Health Aff (Millwood). 2012;31(1):130–139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kowitt SD, Ayala GX, Cherrington AL, et al. Examining the support peer supporters provide using structural equation modeling: Nondirective and directive support in diabetes management. Ann Behav Med. 2017;51(6):810–821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Kowitt SD, Urlaub D, Guzman-Corrales L, et al. Emotional support for diabetes management: An international cross-cultural study. Diabetes Educ. 2015;41(3):291–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Kim HS, Sherman DK, Taylor SE. Culture and social support. Am Psychol. 2008;63(6):518–526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Dutton YE. Butting in vs. being a friend: Cultural differences and similarities in the evaluation of imposed social support. J Soc Psychol. 2012;152(4):493–509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Reese RJ, Conoley CW, Brossart DF. Effectiveness of telephone counseling: A field-based investigation. J Counsel Psychol. 2002; 49(2):233. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Fisher EB, Boothroyd RI, Elstad EA, et al. Peer support of complex health behaviors in prevention and disease management with special reference to diabetes: Systematic reviews. Clin Diabetes Endocrinol. 2017;3:4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Uchino BN, Trettevik R, Kent de Grey RG, Cronan S, Hogan J, Baucom BRW. Social support, social integration, and inflammatory cytokines: A meta-analysis. Health Psychol. 2018;37(5):462–471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Chen E, Langer DA, Raphaelson YE, Matthews KA. Socioeconomic status and health in adolescents: The role of stress interpretations. Child Dev. 2004;75(4):1039–1052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Kopp MS, Réthelyi J. Where psychology meets physiology: Chronic stress and premature mortality—The Central-Eastern European health paradox. Brain Res Bull. 2004;62(5):351–367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Siegrist J, Bellingrath S, Kudielka BM. Stress and Emotions. In Fisher EB, Cameron LD, Christensen AJ, Ehlert U., Guo Y, Oldenburg B, Snoek FJ, eds. Principles and Concepts of Behavioral Medicine: A Global Handbook. New York, NY: Springer; 2018: 319–340. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Slopen N, Glynn RJ, Buring JE, Lewis TT, Williams DR, Albert MA. Job strain, job insecurity, and incident cardiovascular disease in the Women’s Health Study: Results from a 10-year prospective study. PLoS One. 2012;7(7):e40512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Karasek RA, Theorell T.. Healthy Work. New York, NY: Basic Books; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 38. Hartley TA, Burchfiel CM, Fekedulegn D, Andrew ME, Violanti JM. Health disparities in police officers: Comparisons to the U.S. general population. Int J Emerg Ment Health. 2011;13(4):211–220. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Ryan V. (2018). Theresa May appoints minister for loneliness, after Jo Cox Commission highlight Britain’s epidemic. Available at https://www.telegraph.co.uk/politics/2018/01/16/theresa-may-appoints-minister-loneliness-jo-cox-commission-highlight/. Accessibility verified November 7, 2019.