Abstract

Global change causes widespread decline of coral reefs. In order to counter the anticipated disappearance of coral reefs by the end of this century, many initiatives are emerging, including creation of marine protected areas (MPAs), reef restoration projects, and assisted evolution initiatives. Such efforts, although critically important, are locally constrained. We propose to build a “Noah's Ark” biological repository for corals that taps into the network of the world’s public aquaria and coral reef scientists. Public aquaria will serve not only as a reservoir for the purpose of conservation, restoration, and research of reef-building corals but also as a laboratory for the implementation of operations for the selection of stress-resilient and resistant genotypes. The proposed project will provide a global dimension to coral reef education and protection as a result of the involvement of a network of public and private aquaria.

Global change is causing a widespread decline in coral reefs. This Community Page article proposes to build the World Coral Conservatory, a “Noah's Ark” biological repository that taps into the network of the world’s public aquaria and coral reef scientists, in order to preserve the fast-disappearing biodiversity of coral reefs.

Introduction

Reef-building corals play a pivotal role in marine ecosystems and constitute the foundation of coral reef ecosystems that represent the world’s most important biogenic structures. Coral reefs provide habitat and trophic support for one-third of all marine organisms, and their biodiversity rivals that of tropical rainforests [1]. In addition to their ecological importance, coral reefs are economically essential for many human societies, with more than 600 million people around the world depending directly on coral reefs for their survival [2–4]. The total annual value of global coral reefs is estimated to be more than US$30 billion/year [5, 6]. However, because of a combination of local and global stressors (pollution, overexploitation of resources, diseases, and climate change), marine ecosystems outpace terrestrial habitats in biodiversity erosion [7]. Coral reefs, the frontrunners of this trend, are declining at an unprecedented rate, making them the most endangered biological systems [8]. De’ath and colleagues have shown that the growth rate of reefs decreased by 15% over a 20-year period [9], and Hughes and colleagues [10] estimated that we lost about 30% of corals from the Great Barrier Reef because of a single coral bleaching (2015–2018) event. Even more alarming, the most recent Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) special report “Global warming of 1.5°C”, released in late 2018, anticipates a likely loss of 90% of reef-building corals by 2100 under a warming scenario of +1.5°C and a virtually complete loss of corals (>99%) under a warming scenario of +2°C [11]. Although certain coral species may have physiological and genomic attributes that make them more resilient/resistant to heat stress [12], a substantial loss of corals and the reefs they build is inescapable. Consequently, we need to establish interventions (for example, [13, 14]) in order to avoid the unmanageable and manage the unavoidable.

Both in situ and ex situ (on-land) actions can be taken to protect and/or restore coral reefs, and both approaches have their advantages and drawbacks as outlined in the following. The vast majority of conservation actions are in situ protection, either through the establishment of marine protected areas (MPAs) or through restoration of degraded coral reefs. The importance and benefits of MPAs are well documented, serving primarily to decrease local stress to increase the resilience of reefs [15–17]. Unfortunately, MPAs currently encompass less than 10% of the surface area of coral reefs [18], and studies suggest that MPAs are limited in their protective scope [19]. Further, MPAs largely protect coral reefs from local threats, but not from global stress. Therefore, they may prove ineffective in the face of climate change. As outlined above, from 2015–2018, the northern part of the Great Barrier Reef, despite being protected and remote from direct anthropogenic impacts, had lost an estimated 30% of its surface of living corals because of coral bleaching triggered by ocean warming [10]. Coral reef restoration has also become an active area of coral reef management [20]. Though local actions are currently limited to small areas (on the order of square kilometers), technological developments could facilitate restoration of larger areas in the future. For instance, the use of more resilient/resistant coral colonies as source material for reef restoration has been suggested, yet it is unclear how thermal tolerance may shift under large-scale warming for extended periods and under the increase in the severity and frequency of marine heatwaves [21, 22]. Consequently, efforts to rebuild reefs through restoration efforts should incorporate knowledge on current and projected resilience/resistance of the corals used for that purpose (see also below).

To address the problem that not all reefs can be saved and to focus efforts on reefs that are most likely to survive in the future, Hoegh-Guldberg and colleagues conducted a global scale analysis to identify resilient regions for which long-term coral reef conservation may be an attainable goal, even under ongoing ocean warming (“50 Reefs Initiative,” [23]). The identified regions are putatively less susceptible to impacts from thermal stress and coral bleaching [23], such as the Persian Gulf [24, 25] or the Red Sea [26–29]. Additionally, different types of reef “oases” were identified by Guest and colleagues [30] in a large-scale comparison of multidecadal time series data, further highlighting reefs of interest with respect to resilience, conservation, and restoration. Although not universal [31, 32], the mesophotic zone between 30 and 150 m [33] is another possible refuge area. Indeed, as shown by Kramer and colleagues [34], its upper part can serve as a refuge for corals and become a source of larvae that can facilitate the recovery of shallow degraded areas, although it is not clear in how far shallow and mesophotic reefs system are genetically connected [32]. Notably, such sites are for the most part identified based on remote-based approaches and observational surveys, disregarding the substantial variation that exists at the level of individual coral colonies/genotypes [35–37].

An alternative for in situ conservation management would be to use ocean warming resilient/resistant specimens for reef restoration purposes. However, natural populations of resilient/resistant corals, such as those from the Persian Gulf, are locally adapted and likely do not prevail in other environments [38, 66]. Given the urgent need to mitigate coral reef declines and the limitations of classic conservation and restoration measures, Van Oppen and colleagues [39] proposed using assisted evolution methods, inspired by more than 10,000 years of selection of resistant strains and environmental hardening approaches followed in agriculture and aquaculture. Briefly, the authors propose to promote resilience/resistance of coral colonies by (1) inducing laboratory stress and selecting the coral colonies that survive, (2) actively modifying the coral-associated microbiota, (3) applying environmental stress hardening to generate more resistant phenotypes, and (4) by genetically enhancing coral host-associated microalgae (Symbiodiniaceae, [40]) by means of mutation and selection using artificial evolution (see also [41–43]). Subsequently, methods for active modification of the coral genome through approaches such as CRISPR and synthetic biology [14] were suggested. These methods require the consideration of both logistical and ethical challenges [44, 45] before field implementation should be attempted.

On-land (ex situ) solutions aim to preserve corals outside their natural environment, with the benefit that such maintained corals are not subject to marine heatwaves or other natural events (for example, hurricanes) that might destroy them. Rather, ex situ solutions provide a more controlled environment where corals are not subject to arbitrary environmental change. At the same time, we acknowledge the diversity of opinion around this topic, and the concern that aquaria conditions ultimately “select” for domestic rather than wild genetic profiles. In other words, corals that are well adapted to “benign” aquaria conditions will do better, which may make it challenging to maintain coral genotypes under aquaria settings that respond well to environmental extremes. The ultimate utility of aquaria as a coral conservatory (and seedbank) will have to be demonstrated, and the best way to do this is by incorporating “the science learned along the way”. Similar to what has been done with vertebrates [46] or crops/plant species [47], initial approaches in corals have entailed the construction of a “vault” to store germinal cells from different coral species to preserve the genetic information of a species and/or particular genotypes. For instance, Hagedorn and colleagues [48–50] successfully cryopreserved coral spermatozoa cells and dissociated embryonic cells. Another alternative is to cryopreserve coral larvae or so-called tissue balls [51, 52]. However, cryopreservation was shown to reduce fertilization success [53] and the techniques are not available off the shelf, with improvement required to be applicable in a standardized and broad manner. Also, further research is needed to assess and understand putative long-term effects and success.

Ex situ culturing builds on the conservation work already carried out by zoos and aquaria for endangered populations of vertebrates and invertebrates [54, 55]. This approach employs a network of aquaria with the benefits of (1) conserving coral species, (2) generating coral material without depleting wild stocks for research into areas such as assisted evolution, and (3) providing a multispecies test bed for the performance and interaction of manipulated corals prior to ex situ culturing and field testing. Given that coral culturing is occurring in numerous research institutes and public aquaria, along with methods of propagating corals through sexual and asexual reproduction also being developed [56], a network of aquaria provides a critical global resource for threatened corals. Of note, in light of the diversity of aquaria water supplies, daily settings, and vertebrate and invertebrate species diversity, such asexually propagated coral fragments will be exposed to a variety of environmental conditions, which should reduce concern for limited plasticity, thus avoiding domestication of corals to an artificial environment.

Aim(s) of the World Coral Conservatory (WCC) project

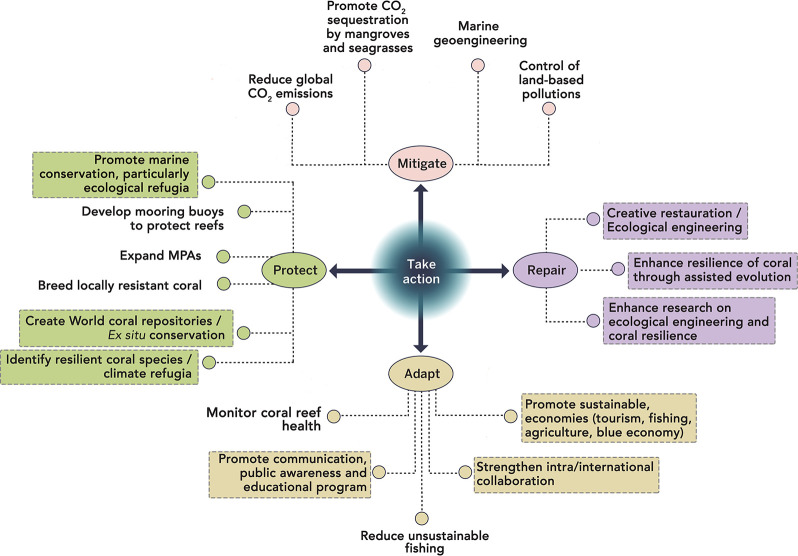

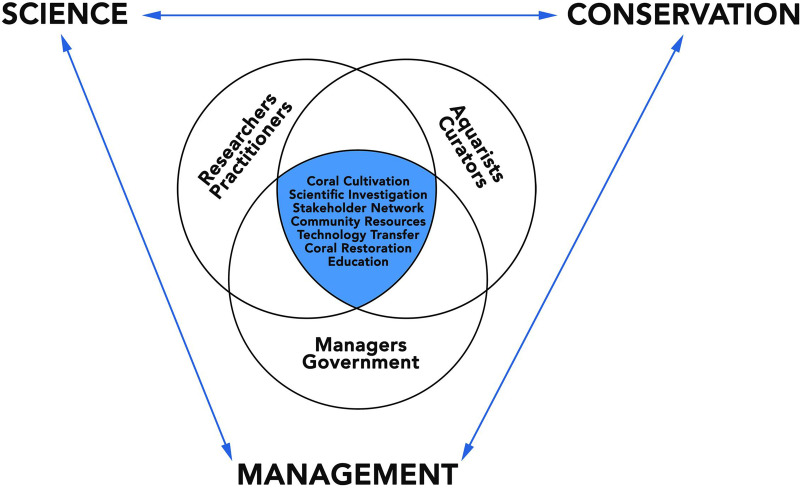

Public aquaria around the world now maintain and present live coral and ensure continuous replication/persistence through so-called cuttings. Emerging from discussions at the “International Coral Reef Symposium 2016” (ICRS2016) in Honolulu (Hawai’i, USA), we propose here the creation of the WCC. This endeavor would take advantage of combining 3 of the 4 safeguarding actions proposed by Allemand and Osborn [57], supporting protection, adaptation, and reparation as solutions for coral reefs against climate change impact (Fig 1). The WCC takes advantage of the existing global network, infrastructure, and facilities of public aquaria as a means to protect the biodiversity of coral reefs via the maintenance, propagation, and study of aquaria-reared reef-building corals. Our solution is based on 3 components: Science, Conservation, and Reef Management (Fig 2).

Fig 1. Solutions for coral reefs against climate change impact supported through the WCC project.

The diagram is based on the 4 clusters of actions proposed by Allemand and Osborn [57] for coral reef ecosystems. Specific solutions supported the WCC are highlighted by colored squares. WCC, World Coral Conservatory.

Fig 2. The WCC is based on a consortium of researchers, aquarium curators, and field managers facilitating the transfer of information between the 3 main components.

MPA, marine protected area; WCC, World Coral Conservatory.

The aims of the WCC are as follows:

To create a repository of living coral colonies that represent the majority of extant species;

To preserve coral genetic and species diversity from a variety of habitats and by this a mechanism to contribute to restore coral reef diversity through reintroduction and reef restoration approaches [58];

To contribute to protecting coral reef biodiversity by developing solution-based approaches that combine reef science, conservation, and management;

To provide researchers from all over the world with referenced and trackable biological material, which also reduces the burden of collection of biological material from coral reef ecosystems and supports standardization via research on shared resources (same coral genotypes);

To use the available biological resources for "assisted evolution approaches" to increase stress tolerance and resilience/resistance; and

To provide comprehensive information on corals and coral reefs to the general public and stakeholders in order to educate and enable people to participate in the collective effort of coral reef conservation. The IPCC Special Report on the Ocean and Cryosphere in a Changing Climate, approved in Monaco in September 2019, highlights education as an essential component as a solution for safeguarding ecosystems.

The urgent need to preserve the unique biodiversity and natural heritage of corals and to minimize harvesting corals from the field for scientific or commercial purposes makes approaches such as the WCC a priority. Notably, we will prioritize coral species based on geographical distribution and population size. For the biological repository, which we term the “coral bank”, state-of-the-art genetic techniques will allow the precise identification of species and genotypes in order to trace colonies from their respective origin and to monitor distribution and spread of daughter colonies (i.e., ramets) for research and propagation. Preservation of genetic diversity within species and populations in the WCC via genotype identification, archiving, and tracing is a prerequisite for successful conservation measures and currently not widely implemented in coral restoration practices.

Methodology and roadmap

The first meeting of the steering committee of the WCC was held in 2019 during the Monaco Ocean Week, and we defined a plan to sample, cultivate, investigate, develop, communicate, restore, and transfer (Fig 2).

The number of coral species currently kept in aquariums is on the order of 250, which represents only a small fraction, around 15%, of the estimated 1,600 coral species globally [59], highlighting the challenge of deciding which species to choose. Should the choice be made between putative climate-resilient/resistant species or between iconic species best representing coral reefs? For instance, corals from the Arabian Seas presumably have increased thermotolerance and are more resistant to bleaching. At the same time, the number of species in the Persian Gulf is limited (about 70 in total). Hence, by choosing a relatively narrow set of expected “winners”, this approach risks eroding global biodiversity [60]. It is therefore essential to take a balanced approach to species selection, which includes first, broad genetic diversity, and second, corals with a variety of specific traits (for example, thermal tolerance, high fecundity, disease tolerance) and from a variety of habitats, shown to contribute to coral performance [61]. The overarching goal is to capture a breadth of genetic diversity to reduce the potential for bottlenecks or tradeoffs that may come with a focus on a few tolerant species or genotypes. To support the initial goal of biodiversity, species will need to be sampled broadly across many locations. Based on our experience from the Tara Pacific Expedition [62] and in order to ensure a breadth of genetic diversity, colonies from each species will be collected in 5 different locations. One of the first regions of interest is therefore the most biodiverse geographic area, the coral triangle (Fig 3). This region contains about 600 species of scleractinian corals out of the 1,600 global species. Furthermore, many countries in this region have the infrastructure and skills to help support coral sampling and global coral dispatching efforts. Indeed, other locations will be chosen, such as the Indian Ocean, the Red Sea, and the Great Barrier Reef. Therefore, in order to maximize the areas where we will be able to collect corals, we have decided to join forces and team up with initiatives that are close to our objectives. These global initiatives include the Great Barrier Reef Legacy (https://greatbarrierreeflegacy.org/), the Association of Zoos and Aquariums, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, and the Mote Marine Laboratory, which are participating in the Florida Reef Tract project (https://www.aza.org/the-florida-reef-tract); further, the Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute in Hawai’i.

Fig 3. The coral triangle denotes the geographical area in the Pacific between Indonesia, the Philippines, and Papua New Guinea and is home to the largest coral species biodiversity in the world; i.e., about 40% of the world coral species are represented in this area.

Map from Worldofmaps.net.

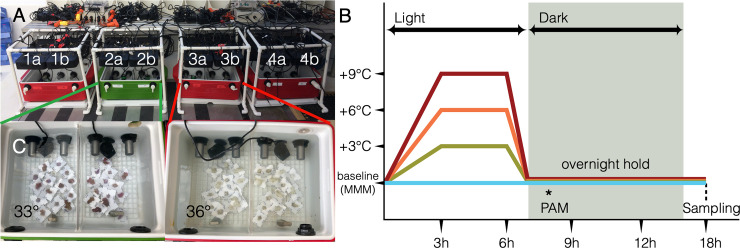

Our second goal is to perform a targeted collection of corals with specific traits. Endemic species should be part of the priority list, given their unique cultural value and potentially interesting genetics and physiology [41, 63, 64]. For example, the Caribbean area, which is under rapid decline, has only 62 described species, but 43 of them are endemic to the region, while endemic Hawaiian species show unique gene family expansion and gene duplication features [65] that will provide insight in comparative studies. Another strategy is to collect tolerant/resistant/resilient genotypes to specific environmental parameters such as thermal stress. The challenge remains how to identify such colonies. While long-term heat stress experiments are useful tools to identify resilient/resistant genotypes and have a track record in the literature [66], they require extensive and expensive aquarium systems and are not practical in remote field locations and settings. Further, the approach takes weeks to months for an assessment of just a single set of individuals from a single population. Recent experiments utilizing short-term acute thermal exposures in remote field settings show a promising ability to reveal fine-scale differences in thermal tolerance across small spatial scales [66–68]. Based on these experiences, Voolstra and colleagues [69] have demonstrated the suitability of standardized short-term acute heat stress assays to resolve intraspecific differences in coral thermotolerance in 2 populations from contrasting thermal environments separated by <500 meters. The Coral Bleaching Automated Stress System (CBASS), a portable, inexpensive, standardized experimental system developed by Barshis, will be used to select stress-resilient colonies for aquaria maintenance ([69] and Fig 4). It uses multiple temperatures to screen for coral colonies with resilient/resistant phenotype characteristics within 1.5 days and allows alignment of determined phenotypes with the underlying genetic/genomic makeup via subsequent molecular analysis. The screening can be extended to incorporate other traits of interest, such as tolerance towards high nutrient levels or other anthropogenic impacts. An increased ability to determine which corals are more resilient/resistant to stressors and their underlying holobiont features (genes, gene variants, Symbiodiniaceae types, associated bacteria) will help to focus efforts on specific genotypes and sites and inform action on conservation and restoration efforts.

Fig 4. Overview of the CBASS.

(A) Picture from Christian R. Voolstra showing CBASS featuring 4 light- and temperature-independent, flow-through tanks with 2 replicate units (1a/b: baseline temperature based on MMM of tested site, 2a/b: MMM +3°C, 3a/b: MMM +6°C, 4a/b: MMM +9°C). (B) 18-hour–long programmed temperature profile for assessment of coral thermal tolerance thresholds. Asterisk = measurement of photosynthetic efficiency as proxy for coral health (see [70]). CBASS, Coral Bleaching Automated Stress System; MMM, maximum monthly mean; PAM, Pulse-Amplitude Modulation.

Because it is paramount that samples are uniquely identified and tracked in their respective native environment, we propose to use transponders for this purpose, as is done, for example, for penguins [70]. The barcode assigned to each colony will be added to the identity card of the colony, which will identify the species by in situ photos, a geographical location of the sample, a genetic barcode, photos of the skeleton, etc. Each colony sent to aquaria or research laboratories will thus be followed and can be related back to its origin.

In addition to the aquarium of Monaco, which was the first in the world to present a life-size living coral reef, public aquariums are now successfully maintaining and cultivating live corals, for example, Océanopolis (France), Nausicaa (France), and Burgers' Zoo (The Netherlands). In total, we anticipate about 50 aquariums to comprise the network of the WCC.

For all coral species that are collected under the WCC, we will provide an assessment of genetic diversity based on collected coral colonies. Further, a reference transcriptome (and genomes where possible) will be produced for each species to address questions regarding the following:

Biodiversity: with more than 13,000 species, the sequencing of nearly 10% of Cnidarians will provide us with a good overview of the species that comprise the phylum Cnidaria;

Evolution: availability of 1,000+ transcriptomes allows us to address fundamental questions of coral evolutionary biology, such as the formation of new species, adaptive radiation, calcification, symbiosis, and the genetics of adaptability in light of climate change;

Biomedical and cosmetic applications: corals offer very interesting aspects concerning aging and regeneration, for which the sequencing of 1,000 transcriptomes will improve our knowledge regarding candidate genes contributing to longevity and the extraordinary resistance to UV exposure. Further, corals can become ecological sentinels, and tests using coral cultures can become an industrial standard of ecotoxicity for cosmetics and other xenobiotics [71];

Biomonitoring: the recent use of environmental Deoxyribonucleic Acid (eDNA) is a major breakthrough [72] because organisms leave DNA traces/fingerprints in their environment, especially seawater. This DNA can be extracted from seawater and the composition of the species present at the site where the water was collected can be determined [73, 74]. However, a data library containing barcodes for each species is needed. The 1,000 transcriptomes will allow for doing this.

The sequencing efforts will result in a massive amount of valuable data for the scientific community and will be made publicly available along with the tracking and metadata.

The WCC is also interested in applying assisted evolution approaches [39] using the available biological material because the ability to develop and maintain improved coral stocks will support the restoration of coral reefs, with hopefully improved resilience and survival. The coral stocks obtained would also provide another source of animals for the home aquarist industry, which would in turn reduce the pressure of collection on natural reef sites.

We think that it is also important to have a network of non-governmental organizations (NGOs) working on reef restoration, such as the “50 Reefs initiative” (Ocean Agency, Global Change Institute at The University of Queensland, and the Wildlife Conservation Society), which aims to identify, preserve, and restore 50 coral reefs around the world as priority reefs for conservation [22]. The WCC, by communicating with this new consortium, could provide local corals when regions become devastated by repeated bleaching events.

The WCC, via its public aquarium network, can play a prominent role in educating various audiences about the state of scientific research, the specific biology of corals, the health state of reefs around the world, their contribution to the world's biodiversity, and the services they provide to humans.

Finally, capacity building is an important aspect to this project; transfer of knowledge and techniques on coral culture (microfragmentation, for example [75]) is necessary to increase the number of public aquaria globally that are able to cultivate corals. This is an important way to contribute to coral restoration because the provisioning of corals is significantly facilitated if the supply site is near the restoration site given that the transport of corals is a delicate and expensive operation. In addition, the corals can act as a novel resource for other public aquaria to obtain corals while avoiding collection of new coral colonies from the wild.

The WCC contains many areas of interest to industry and, in particular, holds promise for the development of biomedical and cosmetic applications. The involvement of industrial actors should provide financial resources to support research and development, which will provide a link for industry to follow their interests but, at the same time, share part of the responsibility to maintain coral reefs as an ecological and economical resource for future generations.

Conclusion

We here lay out the overall vision and mission of the WCC (World Coral Conservatory), an internationally open community of research laboratories, science centers, public aquaria, stakeholders, and national administrations that builds on the idea to use aquaria as a “Noah’s Ark” to preserve corals and to establish a global network and platform for sharing of biological material, and for knowledge generation and exchange to enhance and support conservation and restoration of coral reef ecosystems. This network is based on the principles of sharing of data, organization of conferences, symposia, seminars, congresses, temporary exhibitions, and internet forums and welcomes participation and contribution of industry, schools, associations, divers, and citizens. We set out a call to the community to facilitate the pooling of resources and federate stakeholders around common projects for the good of coral reefs, as proposed by the Coral Bleaching Research Coordination Network (https://u.osu.edu/grottoli.1/coral-bleaching-rcn/). These concerted efforts could then provide decision-makers (governments, communities, local and institutional elected officials), reef-area managers, and users with relevant tools in terms of information, methodologies, and decision support. The global network of public aquaria to house valuable coral reef resources provides an essential link between conservation, research, and education efforts.

Acknowledgments

We thank Alexandra Dias Mota for help with designing Fig 1 and Fig 2.

Abbreviations

- CBASS

Coral Bleaching Automated Stress System

- eDNA

environmental Deoxyribonucleic Acid

- IPCC

Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change

- MPA

marine protected area

- NGO

nongovernmental organization

- WCC

Word Coral Conservatory

Funding Statement

Prince Albert II foundation funded the kickoff workshop of WCC. It had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Reaka-Kudla MJ. Chap. 7—The global biodiversity of coral reefs: a comparison with rain forests: Reaka- Kudla, M., D.E. Wilson, and E.O. Wilson (eds.); 1997. 83–108 p.

- 2.Moberg F, Folke C. Ecological goods and services of coral reef ecosystems. Ecol Econ. 1999; 29(2): 215–33. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Spalding M, Burke L, Wood Sa, Ashpole J, Hutchison J, zu Ermgassen P. Mapping the global value and distribution of coral reef tourism. Marine Policy. 2017; 82: 104–13. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wilkinson C, editor. Status of Coral Reefs of the World. Townsville, Australia: Global Coral Reef Monitoring Network and Reef and Rainforest Research Center; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cesar H, Burke L, Pet-Soede L. The Economics of Worldwide Coral Reef Degradation. Arnhelm, Netherlands: Cesar Environmental Economics Consulting (CEEC); 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Costanza R, d'Arge R, de Groot R, Farber S, Grasso M, Hannon B, et al. The value of the world's ecosystem services and natural capital. Nature. 1997; 387: 253–60. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Eriksson BK, Hillebrand H. Rapid reorganization of global biodiversity. Science. 2019; 366(6463): 308–9. 10.1126/science.aaz4520 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gattuso JP, Magnan A, Billé R, Cheung WWL, Howes EL, Joos F, et al. Contrasting futures for ocean and society from different anthropogenic CO2 emissions scenarios. Science. 2015; 349(6243): aac4722 10.1126/science.aac4722 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.De'ath G, Lough JM, Fabricius KE. Declining Coral Calcification on the Great Barrier Reef. Science. 2009; 323: 116–119. 10.1126/science.1165283 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hughes TP, Barnes ML, Bellwood DR, Cinner JE, Cumming GS, Jackson JBC, et al. Coral reefs in the Anthropocene. Nature. 2017; 546: 82–90. 10.1038/nature22901 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.IPCC. Summary for Policymakers In: Masson-Delmotte V, Zhai P, Pörtner H-O, Roberts D, Skea J, Shukla PR, et al. , eds. Global Warming of 1.5°C. An IPCC Special Report on the impacts of global warming of 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels and related global greenhouse gas emission pathways, in the context of strengthening the global response to the threat of climate change, sustainable development, and efforts to eradicate poverty. Geneva, Switzerland: World Meteorological Organization; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kersting DK, Linares C. Living evidence of a fossil survival strategy raises hope for warming-affected corals. Science Advances. 2019; 5(10): eaax2950 10.1126/sciadv.aax2950 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.National Academies of Sciences E, Medicine. A Research Review of Interventions to Increase the Persistence and Resilience of Coral Reefs. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Anthony K, Bay LK, Costanza R, Firn J, Gunn J, Harrison P, et al. New interventions are needed to save coral reefs. Nature Ecology & Evolution. 2017; 1(10): 1420–2. 10.1038/s41559-017-0313-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ban NC, Adams VM, Almany GR, Ban S, Cinner JE, McCook LJ, et al. Designing, implementing and managing marine protected areas: Emerging trends and opportunities for coral reef nations. J Exp Mar Biol Ecol. 2011; 408(1–2): 21–31. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lamb JB, Williamson DH, Russ GR, Willis BL. Protected areas mitigate diseases of reef-building corals by reducing damage from fishing. Ecology. 2015; 96(9): 2555–2567. 10.1890/14-1952.1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Roberts CM, O'Leary BC, McCauley DJ, Cury PM, Duarte CM, Lubchenco J, et al. Marine reserves can mitigate and promote adaptation to climate change. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2017; 114(24): 201701262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mouillot D, Parravicini V, Bellwood DR, Leprieur F, Huang D, Cowman PF, et al. Global marine protected areas do not secure the evolutionary history of tropical corals and fishes. Nature communications. 2016; 7: 10359 10.1038/ncomms10359 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bruno JF, Côté IM, Toth LT. Climate Change, Coral Loss, and the Curious Case of the Parrotfish Paradigm: Why Don't Marine Protected Areas Improve Reef Resilience? Ann Rev Mar Sci. 2019; 11: 307–34. 10.1146/annurev-marine-010318-095300 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rinkevich B. Rebuilding coral reefs: does active reef restoration lead to sustainable reefs? Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability. 2014; 7: 28–36. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Holbrook NJ, Scannell HA, Sen Gupta A, Benthuysen JA, Feng M, Oliver ECJ, et al. A global assessment of marine heatwaves and their drivers. Nat Commun. 2019; 10(1): 2624 10.1038/s41467-019-10206-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Leggat WP, Camp EF, Suggett DJ, Heron SF, Fordyce AJ, Gardner S, et al. Rapid Coral Decay Is Associated with Marine Heatwave Mortality Events on Reefs. Curr Biol. 2019;29(16):2723–30 e4. 10.1016/j.cub.2019.06.077 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Beyer HL, Kennedy EV, Beger M, Chen CA, Cinner JE, Darling ES, et al. Risk-sensitive planning for conserving coral reefs under rapid climate change. Conservation Letters. 2018; 11(6): e12587 10.1111/conl.12587 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Coles SL, Riegl BM. Thermal tolerances of reef corals in the Gulf: A review of the potential for increasing coral survival and adaptation to climate change through assisted translocation. Mar Poll Bull. 2013; 72: 323–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Howells EJ, Abrego D, Meyer E, Kirk NL, Burt JA. Host adaptation and unexpected symbiont partners enable reef-building corals to tolerate extreme temperatures. Glob Chang Biol. 2016; 22(8): 2702–2714. 10.1111/gcb.13250 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fine M, Gildor H, Genin A. A coral reef refuge in the Red Sea. Global Change Biology. 2013;19(12):3640–7. 10.1111/gcb.12356 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Osman EO, Smith DJ, Ziegler M, Kurten B, Conrad C, El-Haddad KM, et al. Thermal refugia against coral bleaching throughout the northern Red Sea. Glob Chang Biol. 2018; 24(2): e474–e84. 10.1111/gcb.13895 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Osman EO, Suggett DJ, Voolstra CR, Pettay DT, Clark DR, Pogoreutz C, et al. Coral microbiome composition along the northern Red Sea suggests high plasticity of bacterial and specificity of endosymbiotic dinoflagellate communities. Microbiome. 2020;8(1): 8 10.1186/s40168-019-0776-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kleinhaus K, Al-Sawalmih A, Barshis DJ, Genin A, Grace LN, Hoegh-Guldberg O, et al. Science, Diplomacy, and the Red Sea’s Unique Coral Reef: It’s Time for Action. Frontiers in Marine Science. 2020;7: 90. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Guest JR, Edmunds PJ, Gates RD, Kuffner IB, Andersson AJ, Barnes BB, et al. J. Applied Ecol. 2018;-55(6): 2865–2875. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bongaerts P, Riginos C, Brunner R, Englebert N, Smith SR, Hoegh-Guldberg O. Deep reefs are not universal refuges: Reseeding potential varies among coral species. Science Advances. 2017; 3(2): e1602373 10.1126/sciadv.1602373 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rocha LA, Pinheiro HT, Shepherd B, Papastamatiou YP, Luiz OJ, Pyle RL, et al. Mesophotic coral ecosystems are threatened and ecologically distinct from shallow water reefs. Science. 2018; 361(6399): 281 10.1126/science.aaq1614 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bongaerts P, Ridgway T, Sampayo EM, Hoegh-Guldberg O. Assessing the ‘deep reef refugia’ hypothesis: focus on Caribbean reefs. Coral Reefs. 2010; 29(2): 309–27. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kramer N, Eyal G, Tamir R, Loya Y. Upper mesophotic depths in the coral reefs of Eilat, Red Sea, offer suitable refuge grounds for coral settlement. Scientific Reports. 2019; 9(1): 2263 10.1038/s41598-019-38795-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bay RA, Palumbi SR. Multilocus adaptation associated with heat resistance in reef-building corals. Curr Biol. 2014; 24(24): 2952–2956. 10.1016/j.cub.2014.10.044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dixon GB, Davies SW, Aglyamova GA, Meyer E, Bay LK, Matz MV. CORAL REEFS. Genomic determinants of coral heat tolerance across latitudes. Science. 2015; 348(6242): 1460–1462. 10.1126/science.1261224 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lundgren P, Vera JC, Peplow L, Manel S, van Oppen MJ. Genotype—environment correlations in corals from the Great Barrier Reef. BMC Genet. 2013; 14: 9 10.1186/1471-2156-14-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.D'Angelo C, Hume BCC, Burt J, Smith EG, Achterberg EP, Wiedenmann J. Local adaptation constrains the distribution potential of heat-tolerant Symbiodinium from the Persian/Arabian Gulf. The ISME Journal. 2015;9(12):2551–60. 10.1038/ismej.2015.80 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.van Oppen MJH, Oliver JK, Putnam HM, Gates RD. Building coral reef resilience through assisted evolution. Proc Natl Acad Sc. USA. 2015; 112(8): 2307–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.LaJeunesse TC, Parkinson JE, Gabrielson PW, Jeong HJ, Reimer JD, Voolstra CR, et al. Systematic Revision of Symbiodiniaceae Highlights the Antiquity and Diversity of Coral Endosymbionts. Curr Biol. 2018; 28(16): 2570–2580. 10.1016/j.cub.2018.07.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hume BC, D'Angelo C, Smith EG, Stevens JR, Burt J, Wiedenmann J. Symbiodinium thermophilum sp. nov., a thermotolerant symbiotic alga prevalent in corals of the world's hottest sea, the Persian/Arabian Gulf. Sci Rep. 2015; 5: 8562 10.1038/srep08562 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Peixoto RS, Rosado PM, de Assis Leite DC, Rosado AS, Bourne DG. Beneficial Microorganisms for Corals (BMC): proposed mechanisms for coral health and resilience. Front Microbiol. 2017;8: 341 10.3389/fmicb.2017.00341 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Eliason CM, Clarke JA. Cassowary gloss and a novel form of structural color in birds. Science Advances. 2020;6(20): eaba0187 10.1126/sciadv.aba0187 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.van Oppen MJH, Gates RD, Blackall LL, Cantin N, Chakravarti LJ, Chan WY, et al. Shifting paradigms in restoration of the world's coral reefs. Glob Chang Biol. 2017; 23(9): 3437–3448. 10.1111/gcb.13647 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Filbee-Dexter K, Smajdor A. Ethics of Assisted Evolution in Marine Conservation. Frontiers in Marine Science. 2019; 6(20). 10.3389/fmars.2019.00020 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Herrick JR. Assisted reproductive technologies for endangered species conservation: developing sophisticated protocols with limited access to animals with unique reproductive mechanisms. Biol Reprod. 2019;100(5):1158–70. 10.1093/biolre/ioz025 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Charles D. Species conservation. A 'forever' seed bank takes root in the Arctic. Science. 2006; 312(5781): 1730–1731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hagedorn M, Carter VL, Henley EM, van Oppen MJH, Hobbs R, Spindler RE. Producing Coral Offspring with Cryopreserved Sperm: A Tool for Coral Reef Restoration. Sci Rep. 2017; 7(1): 14432 10.1038/s41598-017-14644-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hagedorn M, Pan R, Cox EF, Hollingsworth L, Krupp D, Lewis TD, et al. Coral larvae conservation: physiology and reproduction. Cryobiology. 2006; 52(1): 33–47. 10.1016/j.cryobiol.2005.09.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hagedorn M, van Oppen MJ, Carter V, Henley M, Abrego D, Puill-Stephan E, et al. First frozen repository for the Great Barrier Reef coral created. Cryobiology. 2012; 65(2): 157–158. 10.1016/j.cryobiol.2012.05.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Feuillassier L, Martinez L, Romans P, Engelmann-Sylvestre I, Masanet P, Barthelemy D, et al. Survival of tissue balls from the coral Pocillopora damicornis L. exposed to cryoprotectant solutions. Cryobiology. 2014; 69(3): 376–85. 10.1016/j.cryobiol.2014.08.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Feuillassier L, Romans P, Engelmann-Sylvestre I, Masanet P, Barthelemy D, Engelmann F. Tolerance of apexes of coral Pocillopora damicornis L. to cryoprotectant solutions. Cryobiology. 2014;68(1):96–106. 10.1016/j.cryobiol.2014.01.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hagedorn M, Carter V, Martorana K, Paresa MK, Acker J, Baums IB, et al. Preserving and using germplasm and dissociated embryonic cells for conserving Caribbean and Pacific coral. PLoS ONE. 2012; 7(3): e33354 10.1371/journal.pone.0033354 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Maitland PS. The role of zoos and public aquariums in fish conservation. International Zoo Yearbook. 1995;34: 6–14. 10.1111/j.1748-1090.1995.tb00651.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Mascarelli A. Ecology: Conservation in captivity. Nature. 2013;498(7453): 261–3. 10.1038/nj7453-261a . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Rinkevich B, Shafir S. Ex situ Culture of Colonial Marine Ornamental Invertebrates: Concepts for Domestication. Aquarium Sciences and Conservation. 2000;2(4): 237–50. 10.1023/A:1009664907098 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Allemand D, Osborn D. Ocean acidification impacts on coral reefs: From sciences to solutions. Regional Studies in Marine Science. 2019;28:100558 10.1016/j.rsma.2019.100558. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Clements CS, Hay ME. Biodiversity enhances coral growth, tissue survivorship and suppression of macroalgae. 2019;3(2): 178–182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hoeksema BW, Cairns S. World List of Scleractinia. http://www.marinespecies.org/scleractinia/aphia.php?p = stats2019.

- 60.Webster MS, Colton MA, Darling ES, Armstrong J, Pinsky ML, Knowlton N, et al. Who Should Pick the Winners of Climate Change? Trends Ecol Evol. 2017;32 (3): 167–173. 10.1016/j.tree.2016.12.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Safaie A, Silbiger NJ, McClanahan TR, Pawlak G, Barshis DJ, Hench JL, et al. High frequency temperature variability reduces the risk of coral bleaching. Nature Communications. 2018;9(1): 1671 10.1038/s41467-018-04074-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Planes S, Allemand D, Agostini S, Banaigs B, Boissin E, Boss E, et al. The Tara Pacific expedition—A pan-ecosystemic approach of the “-omics” complexity of coral reef holobionts across the Pacific Ocean. PLoS Biol. 2019; 17(9): e3000483 10.1371/journal.pbio.3000483 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Becker LC, Mueller E. The culture, transplantation and storage of Montastraea faveolata, Acropora cervicornis and Acropora palmata: What we have learned so far. Bulletin of Marine Science. 2001;69(2): 881–96. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Young CN, Schopmeyer SA, Lirman D. A Review of Reef Restoration and Coral Propagation Using the Threatened Genus Acropora in the Caribbean and Western Atlantic. Bulletin of Marine Science. 2012; 88(4): 1075–98. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Shumaker A, Putnam HM, Qiu H, Price DC, Zelzion E, Harel A, et al. Genome analysis of the rice coral Montipora capitata. Scientific Reports. 2019;9(1): 2571 10.1038/s41598-019-39274-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Jokiel PL, Coles SL. Effects of temperature on the mortality and growth of Hawaiian reef corals. Mar Biol. 1977;43: 201–8. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Morikawa MK, Palumbi SR. Using naturally occurring climate resilient corals to construct bleaching-resistant nurseries. Proc Natl Acad Sci. USA 2019; 116:10586–10591 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Ziegler M, Seneca FO, Yum LK, Palumbi SR, Voolstra CR. Bacterial community dynamics are linked to patterns of coral heat tolerance. Nat Commun 2019; 8:14213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Voolstra CR, Buitrago‐López C, Perna G, et al. Standardized short‐term acute heat stress assays resolve historical differences in coral thermotolerance across microhabitat reef sites. Glob Change Biol. 2020; 26: 4328–4343. 10.1111/gcb.15148 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Saraux C, Le Bohec C, Durant JM, Viblanc VA, Gauthier-Clerc M, Beaune D, et al. Reliability of flipper-banded penguins as indicators of climate change. Nature. 2011;469(7329): 203–206. 10.1038/nature09630 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Fel J-P, Lacherez C, Bensetra A, Mezzache S, Béraud E, Léonard M, et al. Photochemical response of the scleractinian coral Stylophora pistillata to some sunscreen ingredients. Coral Reefs. 2019;38(1): 109–122. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Stat M, Huggett MJ, Bernasconi R, DiBattista JD, Berry TE, Newman SJ, et al. Ecosystem biomonitoring with eDNA: metabarcoding across the tree of life in a tropical marine environment. Sci Rep. 2017; 7(1): 12240 10.1038/s41598-017-12501-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Nichols PK, Marko PB. Rapid assessment of coral cover from environmental DNA in Hawai'i. Environmental DNA. 2019;1(1): 40–53. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Shinzato C, Zayasu Y, Kanda M, Kawamitsu M, Satoh N, Yamashita H, et al. Using Seawater to Document Coral-Zoothanthella Diversity: A New Approach to Coral Reef Monitoring Using Environmental DNA. Frontiers in Marine Science. 2018;5(28). 10.3389/fmars.2018.00028 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Page CA, Muller EM, Vaughan DE. Microfragmenting for the successful restoration of slow growing massive corals. Ecological Engineering. 2018;123: 86–94. [Google Scholar]