Although cancer incidence and mortality are increasing worldwide regardless of economic development levels,1 the heaviest burden of this escalation is borne by low- and middle-income countries (LMICs).2 Approximately three quarters of deaths from cancer occur in LMICs.3 The rapid rise of cancer in LMICs has created an untenable strain on already overtaxed systems, leaving many patients without adequate care. LMICs have finite resources and thus must invest in areas in which maximum health gains can be made.

To realize health equity in cancer, the importance of the diagnostic laboratory cannot be overstated.6 As recently as 2017, only one quarter of LMICs reported having pathology services available in the public sector.3-5 Being unable to access pathology services results in delayed and incomplete diagnoses, inappropriate treatment decisions, and worsened prognoses, which ultimately result in higher mortality rates.7 Although patients with cancer in LMICs may benefit from long-established effective treatments as well as new and targeted treatment protocols, accurate diagnoses are necessary to assign the correct treatment protocol in the first place.8 It is vital then, that resource-restricted governments prioritize diagnostic services at the policy and health system level, proportionate to their prioritization of treatment services.9

The List of Essential Medicines (EML), List of Essential In Vitro Diagnostics (EDL), and List of Priority Medical Devices for Cancer Management, published by the World Health Organization (WHO), were created as pragmatic guides for the strategic procurement of medicines and diagnostics to be used in resource-constrained settings and by middle- and high-income countries.3-5 The lists include medicines, diagnostics, and equipment that should be widely available and affordable throughout a country’s health care system.3-5 Pharmaceuticals alone represent the second largest public expenditure in health care systems,3-5 so these lists serve as a vital tool for resource-constrained health care systems, ensuring that they receive the best value possible for their patients within the available budgetary resources. For the lists to be effective in advancing cancer care, they must be used in combination with each other and must reflect harmonization across the cancer spectrum. As evidenced by global efforts to combat infectious diseases such as tuberculosis and malaria, attempts to curb disease burden are impossible without pathology services to guide decisions regarding therapy.10 Policy makers, when procuring therapeutic drugs, must also reference the EDL and the List of Priority Medical Devices for Cancer Management to ensure that their health care facilities are appropriately outfitted with the infrastructure and reagents necessary for accurate treatment planning for the procured drugs.10

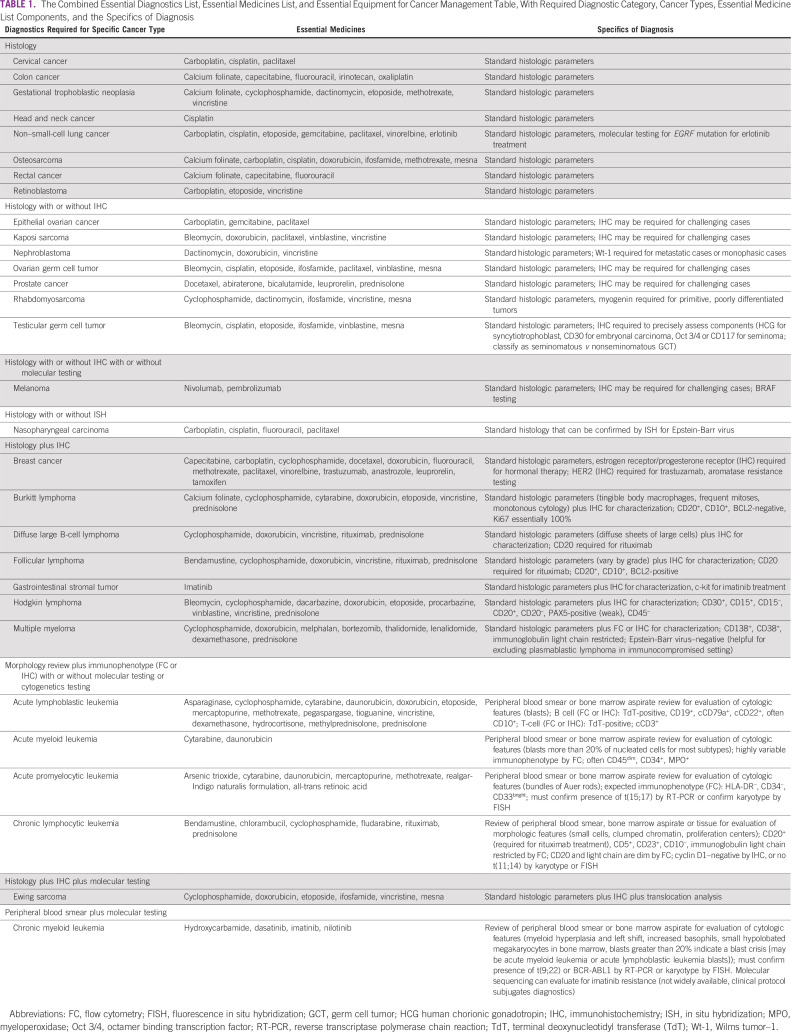

To move toward this harmonization, the 2019 EML was matched to the existing EDL and updated by pathology experts to provide the full details of diagnostic tools needed to effectively use these treatments. Construction of this table was completed using a stepwise approach. First, the EML was reviewed and listed cancer diagnoses were extracted. Second, all agents from the EML that treat those specific cancers were collected by cancer type. Third, for each cancer type, a category of diagnostics required for initial definitive diagnosis was assigned and the cancers were sorted according to category. Finally, the specific details of making a complete diagnosis to indicate a specific treatment were inserted (D.A.M. Jr), checked by experts (E.A.M., J.E.B., J.L.K.), and rechecked by secondary experts (H.M.R., R.G.). Finally, oncologists (Y.M.M., T.F., L.N.S.) reviewed the list of medicines to modify tumor categories that could be treated with the existing list of medications.

Table 1 presents an aggregation of key information from the three Essential Lists. It provides a strategic roadmap for procuring cancer drugs based on available pathology services, and inversely acts as a roadmap for procuring reagents and equipment on the basis of available therapeutics. The table also highlights possible additional indications that a health care institution may be capable of identifying and treating based on what is already available. By combining the three Essential Lists into a single streamlined source, policymakers can use it while considering the entire care pathway when making procurement decisions for patients with cancer to ensure that each purchased component functions within an effective, cohesive system.

TABLE 1.

The Combined Essential Diagnostics List, Essential Medicines List, and Essential Equipment for Cancer Management Table, With Required Diagnostic Category, Cancer Types, Essential Medicine List Components, and the Specifics of Diagnosis

A review by oncology experts of the complete list of essential medicines in the published list reveals that additional tumor types that are not currently listed can also be treated, including gastric, esophageal, anal, pancreatic, hepatocellular, urothelial, small cell, and renal cell carcinomas, cholangiocarcinoma, and some soft-tissue sarcomas. In addition, there are rare cancers that can be treated with some of the listed agents; referring to the US Food and Drug Administration approval lists by cancer type can identify the correct match for diagnosis and treatment along with appropriate protocols. In consideration of these unlisted tumors, additional diagnostic tools should be made available, including immunohistochemical (IHC) stains for parsing a differential diagnosis (depending upon the population epidemiology) and therapeutic IHC stains for immuno-oncology agents. It is important to note, for example, that pembrolizumab is mentioned as a first-line therapy option for metastatic or unresectable melanoma but is, in fact, a second-line therapy for patients with any unresectable or metastatic microsatellite instability-high or mismatch repair deficient solid tumor who have no alternative standard therapy.

It is crucial that the Essential Lists be updated and expanded in a coordinated fashion to ensure that the information presented in each list is complimentary and in sync with the other lists. Otherwise, the effectiveness of the Essential Lists might be called into question, because functioning cancer care requires access to reagents, complex equipment, and medicines in combination.11 The WHO should incorporate and disseminate this table—with vetting by a wider audience of experts including LMIC participants—as an additional resource for LMICs that need to make procurement decisions to ensure that all necessary components are being considered. Proper use of the Essential Lists and corresponding table will deliver improved patient outcomes without wasting limited budgetary resources. Ultimately, the coordinated use of diagnostics and therapeutics will give patients the best chances for survival, whereas a lack of matched diagnostics and therapeutics will expose patients to the toxicities of inappropriate treatment without a chance for benefit.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conception and design: Lawrence N. Shulman, Danny A. Milner Jr

Collection and assembly of data: Jane E. Brock, Elizabeth A. Morgan, Jennifer L. Kasten, Danny A. Milner Jr

Data analysis and interpretation: Analise LeJeune, Jennifer L. Kasten, Yehoda M. Martei, Temidayo Fadelu, Henry M. Rinder, Robert Goulart, Lawrence N. Shulman, Danny A. Milner Jr

Manuscript writing: All authors

Final approval of manuscript: All authors

Accountable for all aspects of the work: All authors.

AUTHORS' DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The following represents disclosure information provided by authors of this manuscript. All relationships are considered compensated unless otherwise noted. Relationships are self-held unless noted. I = Immediate Family Member, Inst = My Institution. Relationships may not relate to the subject matter of this manuscript. For more information about ASCO's conflict of interest policy, please refer to www.asco.org/rwc or ascopubs.org/go/site/misc/authors.html.

Open Payments is a public database containing information reported by companies about payments made to US-licensed physicians (Open Payments).

Yehoda M. Martei

Research Funding: Celgene (Inst)

Temidayo Fadelu

Research Funding: Celgene (Inst), Cepheid (Inst)

Henry M. Rinder

Expert Testimony: Cordis

Robert Goulart

Consulting or Advisory Role: Hologic

Lawrence N. Shulman

Research Funding: Celgene

No other potential conflicts of interest were reported.

REFERENCES

- 1.International Agency for Research on Cancer Estimated number of incident cases from 2018 to 2040, all cancers, both sexes, all ages. 2018 https://gco.iarc.fr/tomorrow/graphic-line?type=0&type_sex=0&mode=population&sex=0&populations=900&cancers=39&age_group=value&apc_male=0&apc_female=0&single_unit=500000&print=0

- 2.Hunter N, Dempsey N, Tbaishat F, et al. Resource-stratified guideline-based cancer care should be a priority: Historical context and examples of success. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book. 2020;40:1–10. doi: 10.1200/EDBK_279693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.World Health Organization Cancer Fact Sheet. 2020 https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/cancer

- 4.World Health Organization Essential medicines and health products. 2020 https://www.who.int/medicines/services/essmedicines_def/en/

- 5.World Health Organization New Essential Medicines and Diagnostics Lists published today. 2020 https://www.who.int/medicines/news/2019/updates-global-guidance-on-medicines-and-diagnostic-tests/en/

- 6.Milner DA, Jr, Holladay EB. Laboratories as the core for health systems building. Clin Lab Med. 2018;38:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.cll.2017.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nelson AM, Milner DA, Rebbeck TR, et al. Oncologic care and pathology resources in Africa: Survey and recommendations. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34:20–26. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.61.9767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dayton V, Nguyen CK, Van TT, et al. Evaluation of opportunities to improve hematopathology diagnosis for Vietnam pathologists. Am J Clin Pathol. 2017;148:529–537. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/aqx108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sayed S, Cherniak W, Lawler M, et al. Improving pathology and laboratory medicine in low-income and middle-income countries: roadmap to solutions. Lancet. 2018;391:1939–1952. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)30459-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wilson ML, Fleming KA, Kuti MA, et al. Access to pathology and laboratory medicine services: A crucial gap. Lancet. 2018;391:1927–1938. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)30458-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Anglade F, Milner DA, Jr, Brock JE. Can pathology diagnostic services for cancer be stratified and serve global health? Cancer. 2020;126:2431–2438. doi: 10.1002/cncr.32872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]