Abstract

Experience of violence or abuse from an intimate partner (intimate partner violence, IPV) can result in a variety of psychological and mental health impacts for which survivors may seek psychotherapy or other mental health services. Individuals experiencing IPV may have specific needs and preferences related to mental health care, yet the question of to how best to provide client-centered mental health care in the context of IPV has received little attention in the literature. In this paper, we report on findings from qualitative interviews with 50 women reporting past-year IPV who received care through the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) regarding experiences with and recommendations for mental health services. Participants described client-centered mental health care in the context of recent or ongoing IPV as being characterized by: flexibility and responsiveness around discussion of IPV; respect for the complexity of clients’ lives and support for self-determination; and promoting safety and access to internal and external resources for healthy coping. We discuss findings in terms of their implications for the mental health field, highlighting the need for flexibility in application of evidence-based treatments, improved coordination between therapeutic and advocacy services, and training to enhance competencies around understanding and responding to IPV.

Keywords: intimate partner violence, women, mental health services, patient preferences, Veterans

Intimate partner violence (IPV) includes physical, sexual, psychological, and social forms of violence (e.g., verbal abuse, threats, coercive control, control of economic resources and social relationships) by a current or former partner (Black et al., 2011). It is a prevalent form of interpersonal trauma and serious public health concern, associated with a range of adverse physical, psychological, and social health outcomes. Prevalence is especially high among women; in the United States, approximately one in three women has experienced rape, physical violence, and/or stalking by a current or former intimate partner within their lifetime, and nearly half of all women have been the target of psychological aggression by an intimate partner (Black et al., 2011).

Experience of IPV, though not a mental health condition or diagnosis, may impact mental health and increase risk for symptoms of depression, anxiety, posttraumatic stress, substance abuse, and suicidal ideation (Beydoun, Beydoun, Kaufman, Lo, & Zonderman, 2012; Bonomi et al., 2009; Dichter et al., 2017; Iverson et al., 2013; Ouellet-Morin et al., 2015; Pico-Alfonso et al., 2006). The psychological impact of experiencing IPV may differ based on the context, severity, chronicity, and dynamic pattern (i.e., cyclic, random, chaotic) of the violence (Katerndahl, Burge, Ferrer, Becho, & Wood, 2012). Different forms of IPV often cooccur and evolve over time, and research suggests that psychological IPV is as detrimental to women’s mental health as physical violence (Blasco-Ros, Sanchez-Lorente, & Martinez, 2010; Pico-Alfonso et al., 2006), while experiencing sexual IPV is associated with more severe mental health morbidity (Dichter et al., 2017; Pico-Alfonso et al., 2006).

Psychotherapy in the Context of IPV

Despite the high prevalence of IPV and strong associations with psychological distress, IPV-focused services (such as safety planning, empowerment counseling, legal advocacy, housing and economic support) have historically not been well-integrated with traditional mental health services (e.g., psychotherapy), in some cases by design. Services to support individuals experiencing IPV emerged largely in the 1970s as part of a larger grassroots social change movement that specifically sought independence from – and in some cases rejected – professionalized social and mental health services and treatment, which were seen as apolitical and potentially disempowering to survivors (Fleck-Henderson, 2017; Lehrner & Allen, 2009; Loseke, 1992; Schechter, 1982).

Nevertheless, many women who have experienced IPV may desire and seek mental health care, generally independent from IPV services. Mental health service providers, however, often receive insufficient training in how to conceptualize, identify, and appropriately respond to IPV, and prior research finds poor service coordination and collaboration between mental health and IPV advocacy services (Laing, Irwin, & Toivonen, 2012; Nyame, Howard, Feder, & Trevillion, 2013; Rose et al., 2011; Trevillion, Corker, Capron, & Oram, 2016; Trevillion et al., 2012; Trevillion et al., 2014; Warshaw, Gugenheim, Moroney, & Barnes, 2003).

Mirroring this service divide, IPV has received relatively little attention in the psychotherapy literature (Bogat, Garcia, & Levendosky, 2013). Existing best-practice guidelines for IPV-related mental health intervention (Bogat et al., 2013; Stewart, Vigod, & Riazantseva, 2015; Warshaw & Brashler, 2009; Warshaw, Sullivan, & Rivera, 2013; World Health Organization, 2013) share a common emphasis on provider training regarding IPV dynamics, prioritizing client safety in and outside of therapy, facilitating linkage to community resources and social support, and adhering to principles of trauma-informed care, such as promoting safety, demonstrating trustworthiness and transparency, and prioritizing clients’ voices and care choices (SAMHSA, 2014). Of the small number of studies examining trauma-focused interventions developed or modified for IPV survivors, most have involved modifications of cognitive-behavioral approaches (Warshaw et al., 2013). While cognitive-behavioral treatments have demonstrated efficacy in reducing symptoms of PTSD and depression in some trauma survivors, they do not directly address the many domains affected by longstanding interpersonal trauma, such as ongoing or past IPV (Warshaw et al., 2013). As is true of psychotherapy outcome research more generally, available evidence suggests that psychotherapy can be helpful and that no single approach fits all (Hegarty & Leung, 2017; Warshaw & Brashler, 2009; Warshaw et al., 2013).

Survivor Preferences

A growing body of research speaks to the question of adapting psychotherapy to the needs and circumstances of the client, beyond their diagnosis, and there is increasing evidence to support the efficacy of such tailoring (Norcross & Wampold, 2018). The question of how to make psychotherapy more responsive to client needs is particularly salient in the case of IPV, given the diverse range and complexity of survivors’ experiences and presenting concerns. Several authors have called for more qualitative and mixed-methods research that invites survivors of IPV to describe their mental health-related experiences, preferences, needs, and treatment goals in their own words (Grillo et al., 2019; Trevillion et al., 2014; Warshaw et al., 2013). A 2014 meta-synthesis (Trevillion et al., 2014) of qualitative work conducted outside the United States with mental health service users who had experienced domestic violence (DV, including violence between intimate partners or family members) revealed several areas of client-identified concerns, including but not limited to: a need for greater clinician acknowledgment of the ways in which DV may impact clients’ mental health; the potentially stigmatizing and minimizing effect of receiving a mental health related diagnostic label in response to disclosing DV; a lack of opportunities to discuss and work through DV-related issues at a self-determined pace; experiences of feeling that some clinicians were controlling and did not offer clients choice or input regarding their care plan; and the need to improve communication and coordination of services between mental health and DV-related services to minimize the stress associated with re-telling one’s story to different clinicians. While this prior work lays a solid foundation, additional research is needed to more clearly discern the particular needs and preferences of clients exposed to IPV as opposed to other forms of DV. In addition, given that mental health services are organized – and may therefore be experienced – differently in different countries, further qualitative inquiry with IPV survivors seeking mental health care in United States and other non-represented countries is warranted.

IPV and Mental Health Concerns among Women Veterans and Women Receiving Veterans Health Administration Care

The Veterans Health Administration (VHA) is the nation’s largest integrated healthcare system, incorporating primary, specialty, outpatient, inpatient, and emergency medical care along with mental health and social services to military Veterans and their eligible dependents. Women who have served in the military experience particularly high rates of lifetime IPV compared to women who do not serve in the military (33% vs. 24%; Dichter, Cerulli, & Bossarte, 2011). Emerging research indicates IPV experiences are common among post-9/11 women Veterans and are associated with increased levels of mental health symptoms (Iverson, Vogt, Maskin & Smith, 2017). In recognition of IPV prevalence among the growing population of women Veterans, as well as the growing emphasis on IPV screening and response in healthcare settings, the VHA has been working since 2012 to implement a comprehensive IPV Assistance Program (IPVAP) for patients, their partners, and VA employees (VHA, 2019). Mental health concerns constitute a major contributor to the illness burden observed among women Veteran VHA patients (Frayne et al., 2014), and IPV experience is associated with elevated rates of mental health diagnoses in this population (Dichter et al., 2017). A survey of women Veterans receiving VHA primary care found that 18.5% reported having experienced IPV in the prior year (Kimerling et al., 2016). VHA clinical screening data indicate a positive past-year IPV screening rate of 8.7% among women patients; over half of these patients had a documented mental health diagnosis within the six months following IPV screening, compared with less than a third of those who screened negative (Dichter, Haywood, Butler, Bellamy, & Iverson, 2017).

Despite the high prevalence of IPV among women Veterans, to date most research regarding the mental health needs and preferences of IPV survivors has focused on civilian samples. Iverson and colleagues (2016) began to address this discrepancy through a quantitative assessment of women Veterans’ preferences for counseling related to IPV, and found that Veterans in their sample prioritized individualized counseling focused on physical safety (of self, children, pets) and emotional health (enhancing coping skills and managing mental health symptoms). The study described in this paper explores the question of what constitutes client-centered mental health care in the context of recent/ongoing IPV by drawing on qualitative interviews with a sample of women IPV survivors who receive health care through the VHA, with implications for tailoring mental health services within VHA as well as more broadly for women who experience IPV (Dichter, Sorrentino, et al., 2017).

Method

Data for this paper were collected as part of a larger study of IPV-related health, safety, empowerment, and service engagement and experiences among women VHA patients who self-reported exposure to any form of IPV within the 12 months prior to study enrollment. Qualitative interviews were conducted between November 2016 and July 2018. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards of the Cpl. Michael J. Crescenz VA Medical Center and the VA Portland Health Care System.

Participants

Interviewees.

Participants in the qualitative interviews were 50 women VHA patients receiving care at one of two large VHA medical centers, one located in the Mid-Atlantic, the other in the Pacific Northwest. The average age of participants was 45 years (range: 22 to 64); 38% identified as black or African American, 40% as white. Forty-seven (94%) had served in the military, while three were non-Veterans receiving care from VHA as the eligible dependent of a Veteran. All participants reported past and/or ongoing engagement in mental health care (not necessarily related to IPV), including contacts with clinicians providing psychotherapy and/or pharmacotherapy, although this was not a criterion for study eligibility.

Qualitative team qualifications and roles.

Two IPV experts who have conducted IPV-related service needs and IPV intervention research with both civilian and Veteran populations were involved in all aspects of study design, implementation, analysis and interpretation (KMI and MED). The qualitative team was comprised of five doctoral-level (KMI, AT, GT, SN, and MED) and two masters-level (AES and MC) researchers with substantive methodological and/or relevant content expertise (intimate partner violence, women Veterans’ health, mental health, qualitative methods), as well as familiarity with salient features of the local organizational context in which data were collected. Data collection was conducted by three team members (AES, AT, and SN) with extensive prior training and experience in conducting research interviews on sensitive topics. The entire team contributed to codebook development, with dataset coding performed by four team members, who served as internal auditors of each other’s work (further details below). The analysis on which this paper is based was led by the first and last authors, with contributions from the larger team.

Materials

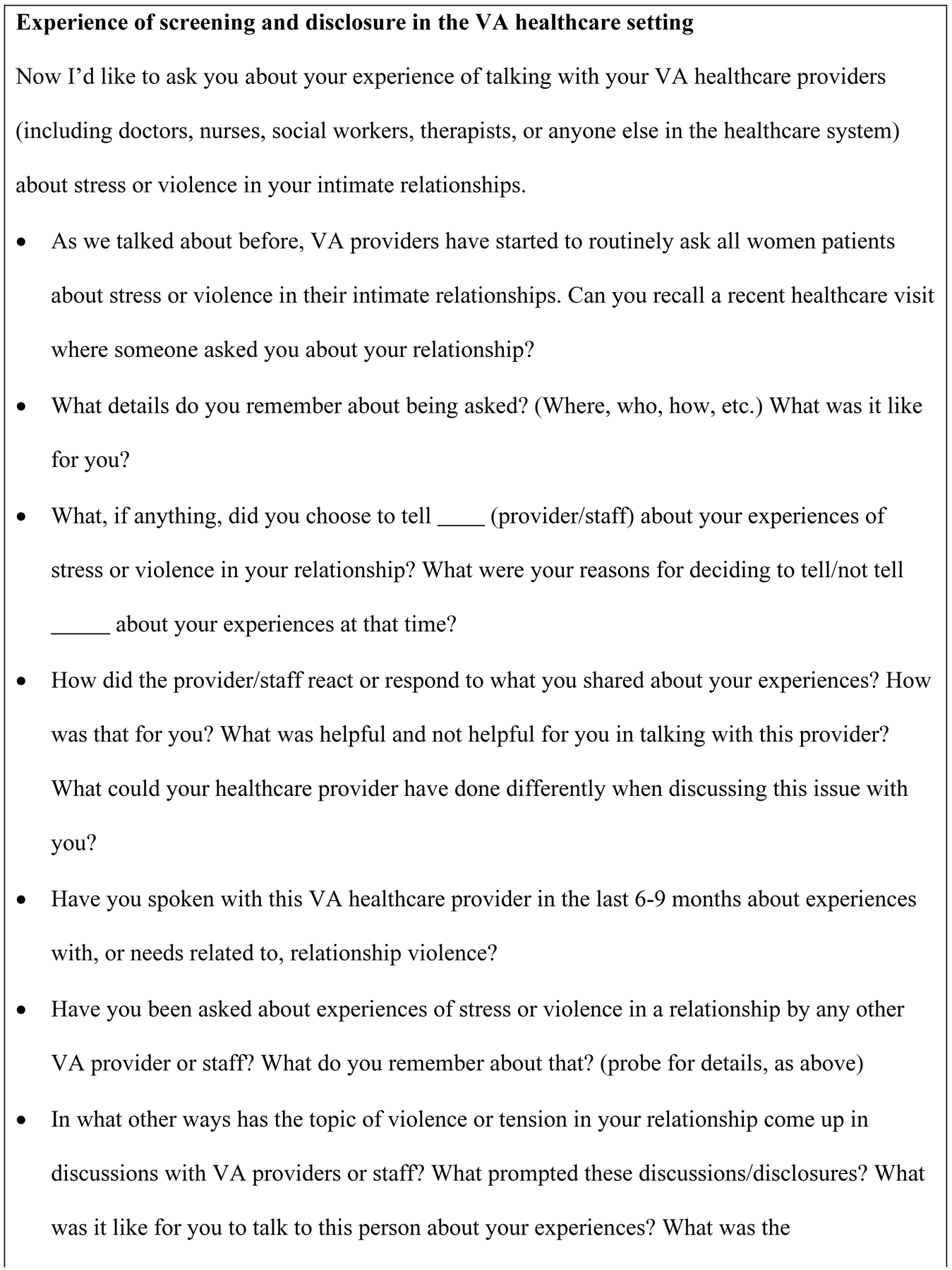

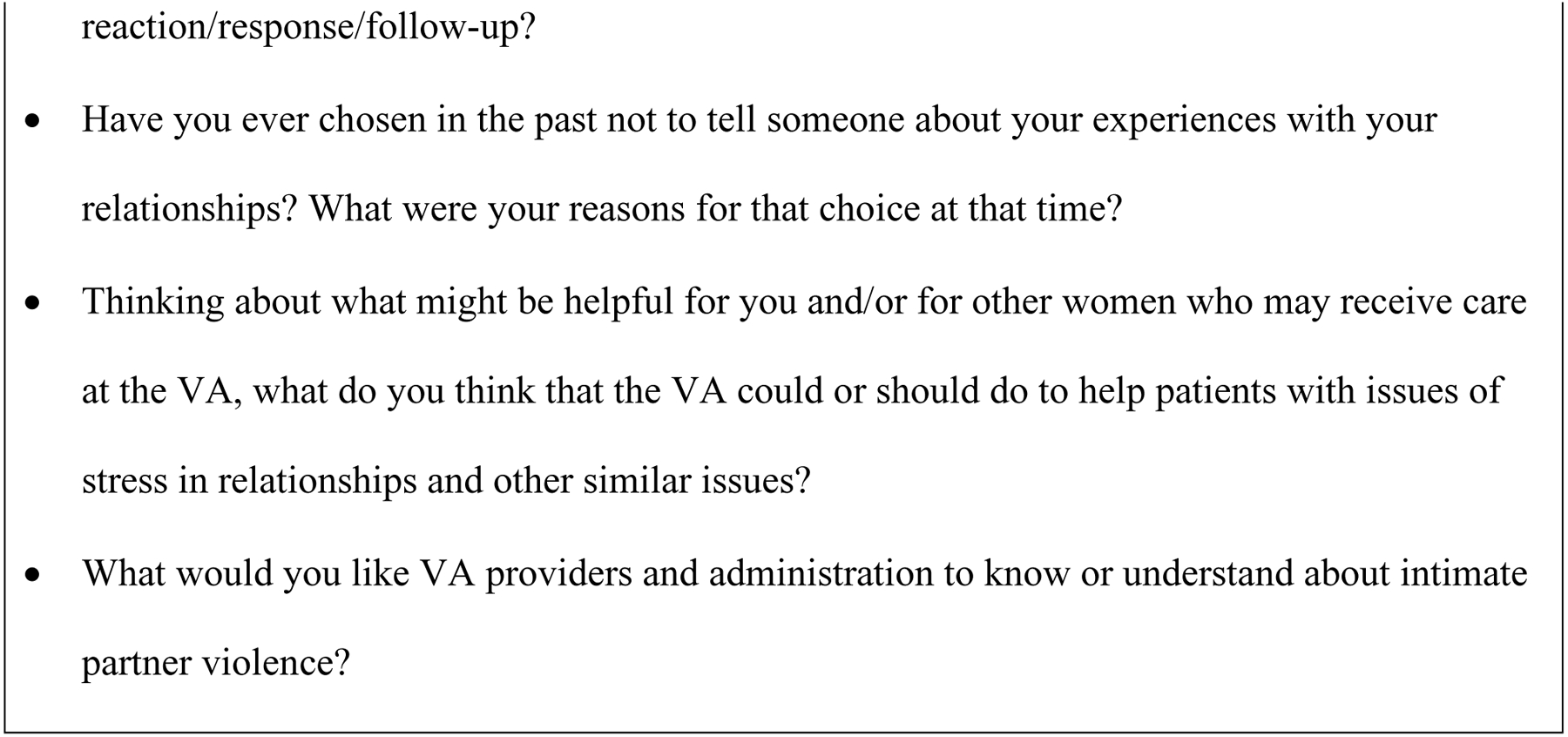

Semi-structured interview.

Interviews were semi-structured and guided by a flexible interview protocol designed by the qualitative team to elicit participants’ experiences of and perspectives on IPV screening, disclosure, and response (immediate and longer-term) in the VHA healthcare setting. The protocol focused first on experiences in primary care or women’s health (where routine IPV screening had been implemented) and then probed for additional experiences in other care settings, including mental health. Stories about experiences with mental health care providers emerged in this context. Figure 1 lists the questions that generated the bulk of data used for the present analysis.

Figure 1.

Interview questions

We also collected basic demographic information as part of the larger study, including participant age, race or ethnicity, and military service history.

Procedure

Recruitment of participants.

As part of the larger study, we sought to enroll a convenience sample of 80 participants from each study site to complete structured interviews at baseline and six to nine-month follow-up (see Dichter et al., 2019, for further details). We selected a subset of this larger sample (25 per site, for a total of 50) to complete semi-structured qualitative interviews at follow-up; participants in the qualitative interviews were sampled on the basis of their interest, availability, willingness to participate in an audio-recorded interview, and with an eye toward achieving diversity in site-level demographics, IPV experiences, and engagement with IPV-related services. All participants had completed informed consent as part of the larger study and reiterated their consent to an audio-recorded interview at the time of the follow-up visit.

Interviews.

Qualitative interviews were completed face-to-face in a private room at the local VHA facility, with the exception of one interview conducted by telephone. Interviews were audio-recorded and lasted, on average, just over one hour (mean across both sites: 64 minutes; range: 26 minutes to 145 minutes. Participants received $50 as compensation for their time and effort.

Confidentiality, transcription, and data preparation.

All participants were assigned a study identification number to protect their confidentiality. Interviews were transcribed verbatim, de-identified, and checked for accuracy, then imported into Atlas.ti (Version 7) for coding and analysis.

Data analysis.

We used a team-based, general inductive approach to data analysis (Thomas, 2006), reflecting the exploratory objectives of our investigation. The first author maintained a detailed audit trail throughout all phases of analysis through a combination of process notes and archiving of project documents related to instrument development and data reduction, analysis, and synthesis products.

Codebook development.

An initial set of descriptive codes was generated by the first and last authors based on overall study aims and close reading of early transcripts, and then shared, discussed, and revised with the larger team. The coding team then piloted and further developed this preliminary list using an iterative process of (a) independently coding the same transcript and (b) meeting to compare coding and discuss refinements to the codes. Once all differences were resolved and team members felt confident that the codes adequately captured key dimensions of interest, a master codebook was created, with code definitions and criteria for inclusion/exclusion. To establish consistency in code application, rotating pairs of coders independently coded a subset of transcripts from each site; partners then compared coding to identify discrepancies and questions, which were discussed during coding meetings and resolved through consensus. The coding team repeated this process until comparisons of coding revealed no significant discrepancies and coders agreed that no further changes to the codebook were necessary. The final codebook included a family of codes designed to capture discussion of important systems, actors, and external resources (formal and informal) in the participant’s social network; within this family, a broad code labeled “Mental Health” captured feedback and reflections on experiences with outpatient and inpatient mental health services, including clinicians, support staff, and services as a whole.

Coding and interview summaries.

Transcripts were assigned to rotating cross-site pairs of coders consisting of a “primary” and a “secondary” coder, such that each transcript was reviewed by one coder from each study site. The primary coder completed line-by-line coding of the transcript; the secondary coder then audited the coded transcript, provided written feedback about areas of disagreement or oversight, and drafted a templated summary of the interview. Throughout the coding process, the coding team met regularly to review and resolve any coding questions or unresolved differences between coders through consensus. This process had the advantage of fostering congruence in coding habits and mitigating coder drift.

Derivation of themes.

Following this process of data reduction, the first author inductively analyzed the subset of data coded to “Mental Health,” through an iterative process of immersion in the data and further data reduction, analytic memoing, and consultation with the larger team.

The first step in this process involved reviewing all text segments coded to “Mental Health” in context and “renaming” segments relevant to the analysis using the quotation title feature in Atlas.ti, which enables the analyst to assign a unique label capturing the main idea of any text segment. Further, review of the templated case summaries created during the initial coding process provided helpful context for this analysis. Next, memos for individual participants were used to summarize relevant mental health related content, as well as note salient themes and illustrative quotes. While the focus was on mental health experiences related to IPV, participants’ comments about mental health related experiences and attitudes more generally were also summarized. This process yielded a set of memos that facilitated comparisons across cases and development of overarching themes with supporting data.

Preliminary themes resulting from this process were then shared and further refined in collaboration with the last author (principal investigator), whose expert knowledge of the IPV research literature added perspective and helped frame the emerging findings. This resulted in three overarching themes, which were then shared with the larger team and further refined based on feedback and subsequent checks against the raw data.

Results

Women in our study described client-centered mental health care in the context of recent or ongoing IPV as being characterized by: flexibility and responsiveness around discussion of IPV experiences; respect for the complexity of clients’ lives and support for self-determination; and promoting safety and access to internal and external resources for healthy coping. Each of these themes is described in more detail below, supported by exemplar quotes from the interview transcripts.

Flexibility and Responsiveness around Discussion of IPV Experiences

Participants’ accounts attest to the therapeutic value of disclosing and discussing their IPV-related experiences with their mental health clinicians, while highlighting the need for flexibility and choice in whether, when, and how to do so. Some participants talked about how the experience of sharing their story and “being heard” and validated was therapeutic in and of itself. In the context of empathic listening, women described a sense of unburdening and relief:

I finally brought it [IPV experience] up to her [clinician]. … [I felt a] lot of weight lifted off my shoulders.

(Participant A)

[Talking with my clinician] gets it off my chest. … Whatever I tell [him], I feel better about.

(Participant B)

Conversely, other women described negative encounters in which clinicians failed to hold space for and/or validate their experiences with IPV. For example, one participant explained that she discontinued treatment after multiple encounters with a clinician whose approach and focus for treatment clashed with her own priorities and needs, and left her feeling unheard:

All she wanted to do was this cognitive therapy to help me with my anger. She didn’t wanna help me with the problems that I’m having in the marriage, and to me, they’re all one big thing. [When I brought up concerns about my relationship, she said] “We’re not here to talk about this,” … she kept cutting me off and steering me in a different direction. … Sometimes people just need to talk it out. They need to tell their story. They need to feel like they’re being heard. She didn’t wanna hear. She didn’t even wanna hear the story.

(Participant C)

Participants also spoke to the importance of creating conditions that invite and facilitate expression of IPV experiences without requiring it. One participant described how her new clinician helped set her at ease by being present and “non-forceful”:

[She] just talked to me like a human. She didn’t talk to me like I was a victim. … I didn’t feel interrogated. I didn’t feel guarded. … And we just talked. It wasn’t a structured outline, either. It wasn’t a thing of, “Okay, I have a set of questions. I gotta follow these guidelines.”… It wasn’t pushy. It wasn’t a thing of, “We can only talk about this, and if you don’t talk about what I wanna talk about, then” – it was none of that. It was just basically non-forceful.”

(Participant D)

Not everyone wanted or was ready to talk about their IPV-related experiences. Participants’ accounts of both positive and negative clinical interactions conveyed the importance of supporting clients’ physical and psychological safety by accommodating their readiness to share their story and giving them narrative control. For example, one participant expressed appreciation for her clinician’s respect for her boundaries, and allowing her to choose whether to discuss IPV:

She [clinician] respected how receptive I was [to questions about IPV]. [Interviewer: Meaning that you were not that receptive to talking about it?] Meaning, like, I freaking hate talking about it [IPV experience]. [Interviewer: And she respected that and that’s—and you liked that?] Yes, because I am a firm believer that the more you speak about something, the more you bring something like that into light and devote time or energy to it, the more power you’re giving it and the [more] predominant it will be and fresh in your brain.

(Participant E)

Another participant described a wish for clinicians to be patient in response to clients’ reticence, and to remain open and available until clients feel comfortable enough to share more. Asked what she would like clinicians to understand better, she replied:

I guess, kinda understand that… it’s not that I don’t like you, it’s just me. I don’t really wanna talk right now. … I’m not ready to talk about it. [Interviewer: And what would you hope they would do?] I guess just continue to make theirselves available when you’re ready to talk. … Until you get more comfortable.

(Participant F)

In summary, flexibility and responsiveness, as articulated by participants in this study, entailed attunement to client needs, priorities, and readiness to discuss IPV; and providing facilitative conditions that promote relational safety and invite expression at the client’s self-determined pace.

Respect for the Complexity of Clients’ Lives and Support for Self-Determination

Participants described complex life situations and challenging decisions faced in the process of coping with partner violence and its aftermath, and drew attention to the importance of demonstrating recognition of this complexity when working with survivors. One of the important ways in which mental health clinicians can support clients experiencing IPV is to honor the difficulty of the decisions they face and support them in making well-considered choices. As the following quote illustrates, this involves accepting and moving with a client’s ambivalence, helping her consider potential consequences, and respecting her right to determine her own best interests:

They [mental health team] ask me, “How is home?” because they know, because I’ve been seeing them since 2010 and ‘12. And they ask, “How is everything working?” and, “What choices have you made? What choices have you been working on?” and everything like that. And they didn’t say, “You need to leave him,” but, “Whatever makes you feel good, but you know the consequences,” … When I say, “I’m leaving him, give me a place, I found a place,” they’ll agree with me and, “It’s okay if this is what you want to do.” And I see the excitement. I see the glow. They see I’m happy when I’m thinking about doing what I should be doing. And then when I talk about how I’m going to stay and they’ll be like, “Are you sure? Because months ago, you said you’re ready to leave …” So they really work with me and they really let me do what I want to do and stuff like that. … It’s always good.

(Participant G)

Women who choose to stay with an abusive partner may experience a loss of support from family, friends, and others who disapprove or do not understand this decision. In addition, these women may refrain from asking for emotional support because they feel like they have forfeited the right to others’ sympathy. Mental health clinicians are uniquely positioned to mitigate the adverse effects of such isolation by providing an accepting, empathic relational context in which women can talk openly and feel understood without judgment or pressure to terminate the relationship. This was illustrated by a participant married to a Veteran with significant mental health issues as she explained why she discusses her marital problems only with her mental health clinician and not with others:

I talked to [previous and current mental health clinician] because … That’s what I’m there for. That’s what they’re there for - to listen. They want to know what’s going on. I’m telling them what’s going on. But I’m also telling them that I’m dealing with it. I’m staying. I’m not complaining to other people because there’s no sense [in] complaining if I’m going to keep staying. … there’s but so much you can keep saying over and over again. They [other people] say, “Okay, well, so what are you going to do? Are you going to keep taking this or are you going to go?”

(Participant B)

For clients who decide to leave an abusive relationship, mental health clinicians can play an important role in helping them plan for and follow through with this difficult transition. For example, one participant turned to her mental health team after deciding to end her marriage. Her response to the interviewer’s question about what she needed to reach her stated goal conveyed her perception of the unique support and protection of privacy her clinicians could offer:

Last week when I brought it up to [therapist], he told me that this week we’ll discuss it further and how to go about this, and the process starting. So, support from my [clinician] and encouragement … that will be a big boost for me, because I can’t talk to my pastor … I don’t talk to my church sisters or brothers about my personal business because I just think there are just certain things I don’t want people to know. I’ll talk to my therapist … Because I told him last week, I said, ‘I’m ready.’ And he was like, ‘Okay. We need to dedicate next week’s session towards that.’ I know that we’ll be focused on that today.

(Participant H)

Promoting Safety and Access to Internal and External Resources for Healthy Coping

Decision-making is invariably tied to questions of resources, both internal and external, and participants looked to clinicians to help them cultivate and access both. Some participants experienced therapy as a vehicle for strengthening internal resources (e.g., affect regulation, assertiveness) and gaining insight regarding the recursive interactional patterns maintaining the cycle of abuse. Such skills and insight can in turn enable clients to positively influence the relational dynamic by shifting their own behavior and responses, increasing safety as well as agency. For example, one participant expressed how the combination of counseling and adjunctive pharmacotherapy for anxiety helped increase her sense of control and choice during conflicts:

My mental health counselor has been a huge help. Taught me to be a little bit stronger. And I’m also taking an anti-anxiety [medication]. So being able to walk away rather than fight it out has been a big help for me in learning how to deal with my anger in my own way, rather than having to stand there and wait for the result or wait to hash it out.

(Participant I)

Another participant who had experienced situational violence with her boyfriend described how therapy has taught her to “mentally process” her own experience and express herself more effectively, which in turn contributes to safer, more productive conflict management:

We talk about a lot of things like where does my fear stem from. We go to the root of the problem to try to uproot that problem. And that’s what helps me the most. Because I can actually say that a lot of the problems that we’ve been talking about have been smoothed… I wouldn’t say really fixed, but very - it’s been a smoother road than before. So I’m able to mentally process. I’m able to realize, like even in situations now where me and my boyfriend have disagreements, I can mentally process that a lot better than before I started talking to him about it. Before it’d just be like, “Well, I’m just not going to talk because this is going to become a huge issue. It might get physical. I’m just going to leave it here.” Now I can feel a lot better about speaking up to my boyfriend. I can feel a lot better about the whole situation mentally. I’m not scared, so to speak. I’m more confident in myself.

(Participant J)

In addition to developing such internal resources, some women experiencing intimate partner violence also sought and desired support in identifying and accessing safety-related resources. Specifically, several participants expressed a wish for their clinicians to provide advocacy and instrumental support around resource navigation:

They need to have action, not just a piece of paper … There has to be some kind of follow-up, some kind of hands-on approach to understanding domestic violence. … they need to be able to actually do something to help an individual get through that. I think that I was having so much of an emotional breakdown that emotionally and mentally I was screaming out for help, and that help I didn’t get. I mean, I got to talk to my therapist a couple times when I came in and they talked to me about a few things here … But it still goes back to you just giving me a freaking piece of paper. I need something more tangible than that … [For example,] “Let’s sit down. Let me just help you and guide you,” or whatever. I didn’t know what I needed. … It’s like you’re at the end of your road. It’s like I’m screaming. I’m yelling at you all. Show me something. Put something here that makes sense. … even if you sit down and someone makes the call with you … That’s supporting. That’s like giving you that hug subliminally.

(Participant K)

Another participant described the emotionally taxing process of seeking legal aid to support her in custody disputes with her abusive ex-partner. The series of rejections she encountered exacerbated her PTSD symptoms to the point that she might have given up; having her mental health clinician make the calls with her provided her with both instrumental and emotional support. As she put it:

You get tired of being turned away so much - or told that they can’t help you. Or, “Try this number, they might be able to help you.” You can only hear it so many times before it’s just like, [I’m] not getting anywhere. … Unfortunately, you kind of need your hand held sometimes.

(Participant L)

Some participants noted that they would have gotten the help they needed sooner had their clinicians been better equipped to guide them toward resources:

[Interviewer: What do you wish her response would have been?] Maybe told me what I could have done to keep him away from me. Because I didn’t know any of that stuff. I didn’t know that I could go get a PFA [protection from abuse order], go get a restraining order. I didn’t know that I can do things to legally protect myself. I learned this when I went to the police station and I [told] the cop, “I’m at my wit’s end. I don’t know what to do” … the cop is the one that told me what to do. Maybe if she [clinician] had done that or said, “[name], there are certain steps you can take to protect yourself. If you go downtown or if you go to the police station,” or things that I can get up from her and go do … [that] probably would have been more helpful.

(Participant M)

Finally, providing instrumental support and advocacy can be deeply therapeutic in its own right, by affirming clients’ humanity and worth, and countering their sense of isolation:

[Clinician] was very – is supportive on a lot of levels – emotionally, of course. She’s also a great advocate as far as trying to help me with … getting out of my abusive situation. … She has given me names of organizations as well. She’s given me apps that I could put on the phone to help me deal with even my own issues within myself … I don’t feel like I’m just another client or I’m just another task. I feel like I’m a human being. She sees me as a human being, not a case number, and, “What do you need? What’s going on? How can I help? Let me know what you need. You can call me any time, if I’m not here leave it on my voicemail, I’ll get back to you in 24 hours.” That type of stuff. And that’s what you need sometimes, somebody that’s in your face. She’s in my face, and I like that.

(Participant D)

Discussion

Individuals who have experienced IPV and seek mental health care have a variety of needs and preferences for the kinds of support they seek from their mental health providers. There is no one-size-fits all strategy for eliciting disclosures or providing counseling for IPV, but there are basic principles for supporting women. Participants in this study offered insights on how to operationalize client-centered mental health care in the context of IPV, highlighting the importance of a flexible, individualized approach that (1) provides opportunities for expression and validation of IPV-related experiences, (2) respects the complexity of each client’s situation and honors her right to determine her own best interests, and (3) promotes safety and adaptive coping by strengthening internal resources and actively facilitating access to external resources and supports.

Our findings add to prior qualitative work regarding IPV survivors’ mental health-related experiences, preferences, and needs (Trevillion et al., 2014), adding the perspectives of survivors seeking care in the United States’ largest integrated healthcare system. Findings augment a growing evidence base regarding what treatment components are helpful for IPV survivors (Arroyo, Lundahl, Butters, Vanderloo, & Wood, 2017; Bailey, Trevillion, & Gilchrist, 2019; Warshaw et al., 2013), and complement qualitative research examining IPV survivors’ perspectives on patient-centered outcomes (Grillo et al., 2019). To a large extent, these findings about client-centered, individualized, and sensitive care will be intuitive to readers, especially clinicians, as they echo well-established assumptions and principles of trauma-informed care (SAMHSA, 2014) and effective clinical practice more generally. However, findings also highlight considerations that are more specific to working with IPV survivors, and that can enhance mental health practice. Key clinical considerations include: flexibility in application of evidence-based treatments, coordination between therapeutic and advocacy services, and competencies around understanding and responding to IPV.

Flexibility in Application of Evidence-Based Treatments

The question of what constitutes client-centered mental health care in the context of IPV highlights a larger issue within mental health practice and research around the operationalization of “evidence-based practice.” Participants’ desire for flexibility and responsiveness around discussion and processing of their IPV experiences aligns with a growing evidence base supporting the efficacy of adapting treatment to transdiagnostic client characteristics (Norcross & Wampold, 2018). Efforts to implement evidence-based treatments have traditionally focused on adherence to a protocol at the expense of flexibility, which can result in overly structured approaches that frustrate clients and clinicians alike (Doran, O’Shea, & Harpaz-Rotem, 2019; Norcross & Wampold, 2019). Client-centered and trauma-informed care for individuals experiencing IPV may require adaptations to treatment approaches that honor individual client circumstances and needs, such as disappointments and safety-related concerns specific to IPV. Fidelity-consistent adaptations to address IPV in the context of evidence-based interventions may optimize women’s health outcomes, while enhancing clients’ receptiveness to, and satisfaction with, treatment.

Coordination between Therapy and Advocacy

Mental health clients who have experienced IPV, like the participants in our study, may desire support from mental health providers in navigating social service resources and systems, support typically offered by IPV advocacy services independent of mental health care. Clinicians’ knowledge of and connection to community-based IPV resources can be helpful for facilitating “warm” referrals, which may be more effective at promoting client follow-through than passive referral methods such as giving clients a resource list (Chamberlain & Levenson, 2012; Ghandour, Campbell, & Lloyd, 2015). Though it may challenge existing structures of care and service delivery, incorporating advocacy interventions (e.g., safety planning and resource navigation) directly into the therapeutic role may be appreciated by clients who prefer not to have to seek services from and share their stories with another provider. As participants in this and other studies made clear (Trevillion et al., 2014), having to re-tell one’s story to multiple service providers is stressful and may increase the risk of re-traumatization, directly (if a client pursues a referral and has a negative experience) or indirectly (if she does not seek/get the support she needs to achieve safety). Incorporating advocacy as a component of psychotherapy thus increases clients’ access to safety-related support, “resists retraumatization” (SAMHSA, 2014), and may also help strengthen the therapeutic alliance and facilitate the overall work of therapy.

IPV Competencies

Effectively responding to mental health clients’ IPV-related needs requires an understanding of and competency in responding to IPV, yet mental health clinicians often lack specific training on how to identify, understand, and respond to IPV (Nyame et al., 2013; Rose et al., 2011; Trevillion et al., 2016). Without such knowledge, including an appreciation of factors influencing decision-making about staying vs. leaving an abusive relationship (Davies & Lyon, 2013; Dunn, 2005; Dunn & Powell-Williams, 2007), clinicians may overlook signs of possible abuse, miss opportunities to facilitate disclosure, reinforce shame and stigma, inadvertently exacerbate risk of harm, and/or fail to effectively support clients’ physical and emotional safety and wellbeing. To effectively support clients, it is critical that clinicians have a working understanding of IPV dynamics generally, and seek to understand the particular dynamics, experiences, and preferences of each individual client, so that interventions match client priorities and needs (e.g., for expression, containment, emotional, and/or instrumental support). It is also helpful for clinicians to be knowledgeable about potential barriers to accessing community resources (McCloskey & Grigsby, 2005; Warshaw & Brashler, 2009), as this knowledge equips them to facilitate more successful linkages (e.g., by helping clients to anticipate potential complications and exploring/addressing client fears or misconceptions). In addition, attention and care to power dynamics in the therapeutic relationship may be particularly important in the context of IPV, to avoid replicating the dynamics of the abusive relationship (Kulkarni, 2019; Warshaw & Brashler, 2009). This points to a need for greater emphasis on IPV in mental health training, including degree preparation programs as well as ongoing professional development and in-service programs that provide opportunities to acquire localized knowledge and learn from peers. Such continuing education opportunities may also enable collaborations and partnerships with IPV-related services in the community.

These findings reinforce and extend clinical recommendations, practices, and tools developed by VHA’s IPV Assistance Program (IPVAP) and other hospital-based domestic violence programs. Despite an increasing emphasis within the VHA on IPV detection and intervention among women Veterans, there are only a few studies examining women Veterans’ perspectives on and preferences for screening and counseling. To our knowledge, this is the first exploration of women Veterans’ experiences with mental health services in the context of experiencing IPV. Findings reinforce the notion that women want options and autonomy in decisions around discussing IPV with providers, including when, how, to whom, and how much to disclose. Many women in this study viewed mental health clinicians as playing an important role in helping women address IPV in their lives. Consistent with IPV screening research emphasizing the role of provider continuity and “connectedness” in facilitating IPV disclosure and care (Iverson et al., 2014), participants’ accounts highlighted the importance of ongoing, attuned, and responsive relationships with mental health clinicians that allow for flexibility in addressing IPV when clients feel ready. Findings also highlight opportunities for maximizing coordination and collaboration between the IPVAP and mental health services, such as by tailoring existing IPVAP trainings for mental health clinicians to address the issues and considerations that emerged in this study. Basic principles to reinforce in clinician trainings include: clinician flexibility and responsiveness, in terms of inviting, facilitating, and following women’s lead around discussion of IPV; adapting evidence-based treatments to incorporate a client-centered focus on IPV; and supporting women’s empowerment and sense of autonomy by strengthening internal (e.g., coping skills and symptom management) and external resources (e.g., facilitating linkages to IPV services and providing education on safety mechanisms such as protection orders). These client-centered strategies are well-aligned with the VHA’s emphasis on trauma-informed and gender-sensitive care for women and are consistent with VHA’s clinical practice directives and tools for screening and counseling for IPV (VHA, 2019).

Limitations

Our findings must be interpreted in light of the study’s limitations. The overall study was not designed to specifically focus on mental health care in the context of IPV; while our interview protocol elicited rich data relevant to this topic, and all participants had experienced some form of mental health care, it is possible that more targeted inquiry would have yielded additional themes and more nuanced findings. We did not systematically collect comprehensive data on the type or timing of mental health services received, and thus were not able to conduct analyses or draw conclusions based on these factors. Although we found strong support for the identified themes, this does not necessarily indicate that these themes are universal or universally strong; rather, these themes highlight areas of importance to select participants that may be relevant to understanding other cases but should not be assumed to apply to all clients. The relatively large qualitative sample (n = 50) and the inclusion of participants from two diverse settings are strengths of the study; however, the sample was limited to female patients receiving care from the VHA who were able and willing to participate in the study. Study findings may not transfer to other settings or populations, including individuals experiencing severe IPV or with particular safety concerns, as well as the substantial portion of women Veterans who seek care outside of the VHA. Finally, while the use of consensus and internal audits during coding and analysis phases strengthened the research, we note that themes were not verified with participants and therefore reflect the research team’s interpretations and understanding of the data.

Conclusion

Participants in this study offered several insights into what constitutes client-centered mental health care in the context of IPV, adding to a small evidence base that privileges survivors’ voices and experientially grounded expertise. The emerging picture highlights the need for continued efforts to bridge the worlds of IPV advocacy and mental health care, and to work toward stronger collaboration across sectors. We are not suggesting that IPV advocacy services can or should be recreated, let alone replaced, by psychotherapy services. However, given the high prevalence of IPV exposure among women and mental health service users, psychotherapists are likely to encounter clients who have experienced or are experiencing IPV; it is our hope that the recommendations emerging from this study may serve to enhance their work with such clients. As demonstrated through survivor narratives, important elements of client-centered care for IPV survivors include provider flexibility and responsiveness, honoring client self-determination and autonomy around difficult life choices, and active support for safety and coping by helping clients develop robust internal and external resources.

Public significance statement:

This study’s findings suggest that client-centered mental health care for survivors of intimate partner violence (IPV) is characterized by a flexible, individualized approach that (1) provides opportunities for expression and validation of IPV-related experiences, (2) respects the complexity of clients’ lives and supports their right to determine their own best interests, and (3) promotes safety and adaptive coping by strengthening internal resources and actively facilitating access to external resources and supports.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by a grant from the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, Health Services Research and Development, IIR 15-142 (Dichter). The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the position or policy of the Department of Veterans Affairs or U.S. Government.

References

- Arroyo K, Lundahl B, Butters R, Vanderloo M, & Wood DS (2017). Short-term interventions for survivors of intimate partner violence: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 18(2), 155–171. doi: 10.1177/1524838015602736 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey K, Trevillion K, & Gilchrist G (2019). What works for whom and why: A narrative systematic review of interventions for reducing post-traumatic stress disorder and problematic substance use among women with experiences of interpersonal violence. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 99, 88–103. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2018.12.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beydoun HA, Beydoun MA, Kaufman JS, Lo B, & Zonderman AB (2012). Intimate partner violence against adult women and its association with major depressive disorder, depressive symptoms and postpartum depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Social Science and Medicine, 75(6), 959–975. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2012.04.025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Black MC, Basile K, Breiding MJ, Smith SG, Walters ML, Merrick MT, … Stephens MR (2011). The National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey (NISVS): 2010 Summary Report. Atlanta, GA: National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. [Google Scholar]

- Blasco-Ros C, Sanchez-Lorente S, & Martinez M (2010). Recovery from depressive symptoms, state anxiety and post-traumatic stress disorder in women exposed to physical and psychological, but not to psychological intimate partner violence alone: A longitudinal study. BMC Psychiatry, 10, 98. doi: 10.1186/1471-244x-10-98 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bogat GA, Garcia AM, & Levendosky AA (2013). Assessment and psychotherapy with women experiencing intimate partner violence: Integrating research and practice. Psychodynamic Psychiatry, 41(2), 189–217. doi: 10.1521/pdps.2013.41.2.189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonomi AE, Anderson ML, Reid RJ, Rivara FP, Carrell D, & Thompson RS (2009). Medical and psychosocial diagnoses in women with a history of intimate partner violence. Archives of Internal Medicine, 169(18), 1692–1697. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2009.292 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chamberlain L, & Levenson R (2012). Addressing intimate partner violence, reproductive and sexual coercion: A guide for obstetric, gynecologic and reproductive health care settings (Second ed.). San Francisco, CA: Futures Without Violence. [Google Scholar]

- Davies J, & Lyon E (2013). Domestic violence advocacy: Complex lives/difficult choices. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Dichter ME, Cerulli C, & Bossarte RM (2011). Intimate partner violence victimization among women veterans and associated heart health risks. Women’s Health Issues, 21(4 Suppl), S190–194. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2011.04.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dichter ME, Haywood TN, Butler AE, Bellamy SL, & Iverson KM (2017). Intimate partner violence screening in the Veterans Health Administration: Demographic and military service characteristics. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 52, 761–768. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2017.01.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dichter ME, Sorrentino A, Bellamy S, Medvedeva E, Roberts CB, & Iverson KM (2017). Disproportionate mental health burden associated with past-year intimate partner violence among women receiving care in the Veterans Health Administration. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 30(6), 555–563. doi: 10.1002/jts.22241 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dichter ME, Sorrentino AE, Haywood TN, Tuepker A, Newell S, Cusack M, & True G (2019). Women’s participation in research on intimate partner violence: Findings on recruitment, retention, and participants’ experiences. Women’s Health Issues. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2019.03.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doran JM, O’Shea M, & Harpaz-Rotem I (2019). In their own words: clinician experiences and challenges in administering evidence-based treatments for PTSD in the Veterans Health Administration. Psychiatric Quarterly, 90(1), 11–27. doi: 10.1007/s11126-018-9604-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn JL (2005). “Victims” and “survivors”: Emerging vocabularies of motive for “battered women who stay”*. Sociological Inquiry, 75(1), 1–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-682X.2005.00110.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn JL, & Powell-Williams M (2007). “Everybody makes choices”: Victim advocates and the social construction of battered women’s victimization and agency. Violence Against Women, 13(10), 977–1001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleck-Henderson A (2017). From movement to mainstream: A battered women’s shelter evolves (1976–2017). Affilia, 32(4), 476–490. [Google Scholar]

- Frayne S, Phibbs C, Saechao F, Maisel N, Friedman S, Finlay A, … Haskell S (2014). Sourcebook: Women Veterans in the Veterans Health Administration. Volume 3. Sociodemographics, utilization, costs of care, and health profile. Washington, DC: Women’s Health Evaluation Initiative, Women’s Health Services, Veterans Health Administration, U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. [Google Scholar]

- Ghandour RM, Campbell JC, & Lloyd J (2015). Screening and counseling for intimate partner violence: A vision for the future. Journal of Women’s Health, 24(1), 57–61. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2014.4885 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grillo AR, Danitz SB, Dichter ME, Driscoll MA, Gerber MR, Hamilton AB, … Iverson KM (2019). Strides toward recovery from intimate partner violence: Elucidating patient-centered outcomes to optimize a brief counseling intervention for women. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 2019, 0886260519840408. doi: 10.1177/0886260519840408 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hegarty K, & Leung TP-Y (2017). Interventions to support the identification of domestic violence, response and healing in mental health care settings. Australian Clinical Psychologist, 3(1), 1740. [Google Scholar]

- Iverson KM, McLaughlin KA, Gerber MR, Dick A, Smith BN, Bell ME, … Mitchell KS (2013). Exposure to interpersonal violence and its associations with psychiatric morbidity in a U.S. national sample: A gender comparison. Psychology of Violence, 3(3), 273–287. doi: 10.1037/a0030956 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iverson KM, Huang K, Wells SY, Wright JD, Gerber MR, & Wiltsey-Stirman S (2014). Women veterans’ preferences for intimate partner violence screening and response procedures within the Veterans Health Administration. Research in Nursing & Health, 37(4), 302–311. doi: 10.1002/nur.21602 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iverson KM, Stirman SW, Street AE, Gerber MR, Carpenter SL, Dichter ME, … Vogt D (2016). Female veterans’ preferences for counseling related to intimate partner violence: Informing patient-centered interventions. General Hospital Psychiatry, 40, 33–38. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2016.03.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iverson KM, Vogt D, Maskin RM, & Smith BN (2017). Intimate partner violence victimization and associated implications for health and functioning among male and female post-9/11 veterans. Medical Care, 55, 78–84. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000000741 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katerndahl DA, Burge SK, Ferrer RL, Becho J, & Wood RC (2012). Understanding intimate partner violence dynamics using mixed methods. Families, Systems, & Health, 30(2), 141–153. doi: 10.1037/a0028603 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimerling R, Iverson KM, Dichter ME, Rodriguez AL, Wong A, & Pavao J (2016). Prevalence of intimate partner violence among women veterans who utilize Veterans Health Administration primary care. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 31, 888–894. doi: 10.1007/s11606-016-3701-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kulkarni S (2019). Intersectional trauma-informed intimate partner violence (IPV) services: Narrowing the gap between IPV service delivery and survivor needs. Journal of Family Violence, 34(1), 55–64. doi: 10.1007/s10896-018-0001-5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Laing L, Irwin J, & Toivonen C (2012). Across the divide: Using research to enhance collaboration between mental health and domestic violence services. Australian Social Work, 65(1), 120–135. doi: 10.1080/0312407X.2011.645243 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lehrner A, & Allen NE (2009). Still a movement after all these years?: Current tensions in the domestic violence movement. Violence Against Women, 15(6), 656–677. doi: 10.1177/1077801209332185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loseke DR (1992). The battered woman and shelters: The social construction of wife abuse. Albany, NY: SUNY Press. [Google Scholar]

- McCloskey K, & Grigsby N (2005). The ubiquitous clinical problem of adult intimate partner violence: The need for routine assessment. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 36(3), 264–275. doi: 10.1037/0735-7028.36.3.264 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Norcross JC, & Wampold BE (2018). A new therapy for each patient: Evidence-based relationships and responsiveness. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 74(11), 1889–1906. doi:doi: 10.1002/jclp.22678 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norcross JC, & Wampold BE (2019). Relationships and responsiveness in the psychological treatment of trauma: The tragedy of the APA clinical practice guideline. Psychotherapy. doi: 10.1037/pst0000228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nyame S, Howard LM, Feder G, & Trevillion K (2013). A survey of mental health professionals’ knowledge, attitudes and preparedness to respond to domestic violence. Journal of Mental Health, 22(6), 536–543. doi: 10.3109/09638237.2013.841871 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ouellet-Morin I, Fisher HL, York-Smith M, Fincham-Campbell S, Moffitt TE, & Arseneault L (2015). Intimate partner violence and new-onset depression: a longitudinal study of women’s childhood and adult histories of abuse. Depression and Anxiety, 32(5), 316–324. doi: 10.1002/da.22347 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pico-Alfonso MA, Garcia-Linares MI, Celda-Navarro N, Blasco-Ros C, Echeburua E, & Martinez M (2006). The impact of physical, psychological, and sexual intimate male partner violence on women’s mental health: Depressive symptoms, posttraumatic stress disorder, state anxiety, and suicide. Journal of Women’s Health, 15(5), 599–611. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2006.15.599 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose D, Trevillion K, Woodall A, Morgan C, Feder G, & Howard L (2011). Barriers and facilitators of disclosures of domestic violence by mental health service users: Qualitative study. British Journal of Psychiatry, 198(3), 189–194. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.109.072389 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SAMHSA. (2014). SAMHSA’s concept of trauma and guidance for a trauma-informed approach. Retrieved from Rockville, MD: [Google Scholar]

- Schechter S (1982). Women and male violence: The visions and struggles of the battered women’s movement. Cambridge, MA: South End Press. [Google Scholar]

- Stewart D, Vigod S, & Riazantseva E (2015). New developments in intimate partner violence and management of its mental health sequelae. Current Psychiatry Reports, 18(1), 1–7. doi: 10.1007/s11920-015-0644-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas DR (2006). A general inductive approach for analyzing qualitative evaluation data. American Journal of Evaluation, 27, 237–246. [Google Scholar]

- Trevillion K, Corker E, Capron LE, & Oram S (2016). Improving mental health service responses to domestic violence and abuse. International Review of Psychiatry, 28(5), 423–432. doi: 10.1080/09540261.2016.1201053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trevillion K, Howard LM, Morgan C, Feder G, Woodall A, & Rose D (2012). The response of mental health services to domestic violence: A qualitative study of service users’ and professionals’ experiences. Journal of the American Psychiatric Nurses Association, 18(6), 326–336. doi: 10.1177/1078390312459747 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trevillion K, Hughes B, Feder G, Borschmann R, Oram S, & Howard LM (2014). Disclosure of domestic violence in mental health settings: A qualitative meta-synthesis. International Review of Psychiatry, 26(4), 430–444. doi: 10.3109/09540261.2014.924095 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veterans Health Administration. (2019). Intimate Partner Violence Assistance Program (VHA Directive 1198). Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. Retrieved from https://www.va.gov/vhapublications [Google Scholar]

- Warshaw C, & Brashler P (2009). Mental health treatment for survivors of intimate partner violence. In Mitchell C & Anglin D (Eds.), Intimate partner violence: A health-based perspective. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Warshaw C, Gugenheim AM, Moroney G, & Barnes H (2003). Fragmented services, unmet needs: Building collaboration between the mental health and domestic violence communities. Health Affairs, 22(5), 230–234. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.22.5.230 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warshaw C, Sullivan CM, & Rivera EA (2013). A systematic review of trauma-focused interventions for domestic violence survivors. Chicago, IL: National Center on Domestic Violence, Trauma & Mental Health. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. (2013). Responding to intimate partner violence and sexual violence against women: WHO clinical and policy guidelines [Internet]. Retrieved from http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/85240/1/9789241548595_eng.pdf?ua=1 [PubMed]