Abstract

The negative impacts of racism, including experiences of racial trauma, are well documented (e.g., Bryant-Davis & Ocampo, 2005; Carter, 2007). Due to the deleterious effects of racial trauma on Black people, interventions that facilitate the resistance and prevention of anti-Black racism are needed. Critical consciousness is one such intervention, as it is often seen as a pre-requisite of resistance and liberation (Prilleltensky, 2003; 2008). In order to understand how individuals advance from being aware of anti-Black racism to engaging in actions to prevent and resist racial trauma, non-confidential interviews with 12 Black Lives Matter activists were conducted. Using constructivist grounded theory (Charmaz, 2014) under critical-ideological and Black feminist-womanist lenses, a model of Critical Consciousness of Anti-Black Racism (CCABR) was co-constructed. The three processes involved in developing CCABR include: witnessing anti-Black racism, processing anti-Black racism, and acting critically against anti-Black racism. This model, including each of the categories and subcategories, are detailed herein and supported with quotations. The findings and discussion provide context-rich and practical approaches to help Black people, and counseling psychologists who serve them, prevent and resist racial trauma.

Keywords: Critical Consciousness, Racial Trauma, Anti-Black Racism, Activism, Black Lives Matter

In 2015 the Institute for the Study and Promotion of Race and Culture unequivocally stated that “racial trauma is real” (Jernigan et al., 2015), a timely assertion given the nationally publicized violence against Black people in the United States (U.S.). Their open access “Racism Recovery Plan” provided a toolkit through which one could better identify and cope with racial trauma. Expanding upon this important work, the current study presents a grounded theory model, co-constructed by racial justice activists, through which Black people can not only cope with, but also prevent and resist racial trauma.

Racial trauma, also referred to as race-based traumatic stress, is the psychological, emotional, and physical injury from experiencing real and perceived racism (Bryant-Davis, 2007; Carter, 2007). Racial trauma accounts for experiences of racism inclusive of overt (e.g., use of racial slurs) and covert (e.g., exclusion based on assumptions of racial inferiority) interpersonal discrimination and harassment, as well as institutional and systemic racism (e.g., systemic excessive use of force by the police; Bryant-Davis & Ocampo, 2005; Carter, 2007). Racial trauma shares symptoms with posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), such as re-experiencing trauma, avoidance, arousal, and negative mood and cognitions (Carter, 2007; Williams, Metzger, Leins, & DeLapp, 2018). However, distinct from PTSD, racial trauma focuses on the cumulative effect of consistent experiences of racism, and historical and generational experiences of racism that are not encapsulated in the diagnostic criteria for PTSD (Carter, 2007; Helms, Nicolas, & Green, 2010). Together, this body of research adds context to the claim that racial trauma is real. Yet, extant literature psychologists serving the Black community primarily focuses on individual level interventions and coping with trauma rather than on prevention and resistance (French et al., 2019).

Recognizing the theoretical, empirical, and practical significance of racial trauma from a psychological perspective, Comas-Díaz, Hall, and Neville (2019) offered a diverse set of articles in the American Psychologist conceptualizing racial trauma for People of Color and Indigenous individuals (POCI) and exploring mechanisms of healing from racial trauma. Given that countless studies make plain the prevalence and deleterious impact of racism (Carter, 2007; Donovan, Galban, Grace, Bennett, & Felicié, 2013; Pieterse, Todd, Neville, & Carter, 2011; Sue, et al., 2008), the focus on healing in the special issue is an important step forward for the field of psychology broadly. With core values of prevention and social justice (Packard, 2009), counseling psychologists are especially well-positioned to expand the work on racial trauma and explore prevention and resistance strategies, ultimately facilitating movement towards liberation.

Counseling psychology history, identity, and ethics suggest that counseling psychologists have been, are, and will be essential in the process of liberation for POCI (Packard, 2009; Pieterse, Hanus, & Gale, 2013; Vera & Speight, 2003; Watts, 2004). Liberation is “the process of resisting oppressive forces and striving toward psychological and political well-being” (Prilleltensky, 2003, p. 195). The stark psychopolitical realities of distinct POCI groups (e.g., continued genocide of Indigenous nations, appropriation of native lands, contemporary forms of slavery) necessitates that counseling psychologists undertake a wide range of liberatory actions (Tuck & Yang, 2012). However, counseling psychologists often fail to center liberation and are susceptible to the psychology wide focus on deficit discourses (Fogarty et al., 2018; Tuck & Yang, 2012). By uncovering the critical consciousness development processes of Black racial justice activists, the current study adds to the literature by shifting the discourse on Blackness to one of resistance and thriving in the face of white supremacy.

Critical consciousness, also known as conscientization or sociopolitical development (as per other scholars in the area, e.g., Freire, 1970; Watts, Williams, & Jagers, 2003) is an intervention to mitigate, prevent, and resist racial trauma (Prilleltensky, 2003). Critical consciousness is when a person becomes aware of and thoughtfully problematizes their lived experience and sociopolitical environments (e.g., exposure to racism) and then engages in actions (e.g., engages in Black racial justice activism) in response to their critical reflection (Diemer, Kauffman, Koenig, Trahan, & Hsieh, 2006). By developing critical consciousness, individuals and collectives can work strategically and systemically towards healing and protection from racial trauma. Critical action is the behavioral component of critical consciousness (Watts, Diemer, & Voight, 2011) and the people who engage in critical action are often called activists (Watts et al., 2003). While critical consciousness development is not a sufficient liberation strategy for all POCI (Tuck & Yang, 2012), the present study illuminates how becoming critically conscious about anti-Black racism (ABR), the “system of beliefs and practices that attack, erode, and limit the humanity of Black people” (Carruthers, 2018, p. 26), promotes healing for Black people.

The Black Lives Matter (BLM) Movement, also referred to as the Movement for Black Lives, represents one popular strategy for liberation focused on African diasporic people (Hargons et al., 2017). BLM activists fight to prevent myriad forms of ABR, including but not limited to physical violence and killings (Hargons et al., 2017). The BLM chapter-based organization created by Patrisse Cullors, Alicia Garza, and Opal Tometi (Garza, 2014) has guiding principles that highlight the importance of approaching efforts toward Black liberation in a manner that includes queer, elderly, incarcerated, and quite literally all other Black individuals (Hargons et al., 2017). In order to equip psychologists with a practical model for preventing and resisting racial trauma that could facilitate healing for diverse Black people, we sought to uncover the critical consciousness development processes of activists who have an inclusive and intersectional vision of liberation, making BLM an appropriate point of departure.

Few studies explore critical consciousness development within specific social movements (Watts & Hipolito-Delgado, 2015). Additionally, there is limited literature available to psychologists who serve Black people impacted by racial trauma (Bryant-Davis & Ocampo, 2006; Comas-Díaz, 2016; French et al., 2019). The current study seeks to fill these gaps and expand the conversation on healing from racial trauma by exploring critical consciousness development among BLM activists. The primary research question was: How do individuals fighting ABR and Black racial trauma in an intersectional manner describe their critical consciousness development?

Method

Two methodological paradigms—critical-ideological and Black feminist-womanist—undergird this qualitative study. The critical-ideological paradigm recognizes one’s subjectivities, the goals for justice inherent in the project, and the researcher’s values (Ponterotto, 2005). The Black feminist-womanist paradigm involves taking an intersectional approach, attending to the different positioning of people based on their social identities, to explore and explain oppression and liberation processes (Collins, 2009; hooks, 1994). From these paradigms, constructivist grounded theory (CGT) methods (Charmaz, 2014) were used.

The CGT approach allows for the voices of BLM activists to be amplified. IRB approval was requested and granted for this study to be non-confidential. Non-confidentiality in psychological research is a newer trend borne out of recognition that confidentiality can limit representation and the extent of critical researchers’ and their participants’ social justice aims (Anderson & Muñoz Proto, 2016). The use of non-confidential video in this study elevates the voices of the participants. It is a strength of the method, as it not only provides transparency and amplification of participant voices, but also ensures their contributions to theory are clear.

Sampling

A purposeful sample (Morrow, 2005) of individuals who engage in activism and explicitly associate with the Movement for Black Lives was recruited. Participants were recruited through online and direct contact methods. In-person recruitment involved distributing flyers at protests, vigils, activist-oriented conferences, and workshops. Online recruitment included posting an advertisement on social media sites using hashtags such as #BlackLivesMatter. Three participants were recruited through snowball sampling methods, which is appropriate when done purposefully and to identify exemplars that can speak to the topic at hand (Morrow, 2005). Interested participants were screened by the first author to ensure they met inclusion criteria: have engaged in actions meant to promote Black liberation; age 18 or over; comfortable being video recorded; comfortable having interview used in future efforts toward increasing critical consciousness of ABR. Participants could self-define their social locations and important identity markers in response to an open-ended interview question. Detailed descriptions of the participant’s social identities are in Table 1.

Table 1.

Participant Demographic Information

| Name, Age | Identities Disclosed | Most Salient Forms of Black Liberation Work |

|---|---|---|

| Geo Borden, 23 | Black Honduran, cisgender woman, androgynous, queer, living in New York, low income, bachelor’s degree, spiritual and non-religious. Did not disclose ability status. | Former student activist, artivist, teacher, scholar-activist, engages in social media-based activism |

| Lauren Chapple, 30 | Black and a quarter German, cisgender woman, straight, living in North Dakota, middle class but feels like a “broke grad student,” graduate student, atheist, vision impairment. | Student activist, scholar-activist, spacemaker, started #updateyourstereotypes campaign |

| Michael Conigan, 30 | Black, cisgender man, straight, from Illinois, working class, believes in God and is seeking answers on spirituality. Did not disclose education level or ability status. | Mentor, neighborhood activist, supports the “village” |

| Michael Cunningham, 50 | Black, cisgender man, gay, from Washington, D.C., working middle class, graduate degree. Did not disclose spirituality or ability status. | Scholar-activist, engages in institutional level campus-based activism, mentor |

| Laina Dawes, 40s | Black, cisgender woman, straight, living in Ontario, raised middle class but feels like a “broke graduate student,” graduate student, agnostic. Did not disclose ability status. | Scholar-activist, artivist/author, mentor, spacemaker for girls |

| Erika Dawkins, 29 | Black, cisgender woman, straight, from Louisiana, middle-class, graduate degree, Christian and “more spiritual than religious,” full-figured. | “Coach,” mentor, spacemaker for Black teenage women |

| Micah McCreary, 60 | Black, cisgender man, straight, from Michigan, upper middle class, graduate degree, Christian, has anxiety and PTSD. | Practices institutional level activism as co-pastor of a church and president of a theological seminary, organizer |

| Aaron Moore, 35 | Black, cisgender man, straight, from Illinois, middle class, altered gait, PTSD. Religion/spirituality and level of education was not disclosed. | Leader of S.A.F.E. Rockford (saferockford.org), community- and youth-focused activist |

| Michael Quess? Moore, 35 | Black, cisgender man, straight, from New York, lower-class income, graduate degree (described as “two pieces of paper”), spiritual and non-religious, has manic depression, social anxiety, and PTSD. | Organizer with Take Em Down Nola (@takeemdownnola or takeemdownnola.org), artivist/poet |

| Michelle Antoinette Nelson, 35 | Black, gender fluid woman, androgynous, lesbian, living in Maryland, middle class, “educated,” spiritual and non-religious. Did not disclose ability status. | Founder of Brown and Healthy (@BrownandHealthy on Twitter and Instagram), artivist/poet, spacemaker |

| Elena Stoodley, 32 | Black Haitian, cisgender woman, straight, from Montreal, very low income, spiritual and non-religious. Did not disclose education level or ability status. | Organizer, community activist, artivist, spacemaker, engages in physical resistance efforts |

| Lamin Swann, 38 | Black, cisgender man, straight, living in Kentucky, middle to upper middle-class income, some college, agnostic, cerebral palsy, has used wheelchair for 25 years. | Practices social media-based activism, organizing, participates in protests, coalition-building |

Data Collection

The initial protocol was developed based on the relevant literature and embodied knowledge of the first author, who actively engages in myriad forms of Black racial justice activism. The interview guide was piloted and revised based on two BLM activists, whose responses were not included in the analysis. The final interview guide included open-ended questions regarding the individual’s (1) activism behaviors, (2) how they came to understand ABR, (3) how they became involved in Black liberation work, and (4) what empowered and sustained them in their activism. Data was collected through intensive interviews with the first author, lasting an average of 73 minutes.

Data Analysis

Data analysis in CGT has three steps: initial, focused and theoretical coding. Data emanates from the interview transcripts and researcher’s memos, which were kept throughout data collection and analysis. The 1st, 3rd, 4th, 5th, and 6th authors, henceforth the research team, assisted in analysis. Transcripts were hand coded, without software, line by line using gerunds. During meetings, the team discussed new insights generated by each team member, highlighting gaps and uncovering potential categories (comparing codes with codes). Meetings allowed space for processing reactions and considerations about positionality to the interviews.

Significant initial codes, those that were most frequent, interesting, or stood out due to their salience to the research question, were identified for focused coding. During this stage, codes were integrated, and their relationships to one another explored (concepts are compared to concepts). For example, groups of focused codes related to approaches to activism (e.g., Being Resourceful) were sorted and compared to one another. When indicated, codes with theoretical reach were elevated to the next level of analysis. Independent concepts were determined to be tentative categories (e.g., Processing ABR) while the concepts that supported that category (e.g., Cognitive Growth) were separated out into subcategories.

With these tentative categories determined, the team began theoretical coding. During this stage we were able to ensure categories were complete, determine relationships between categories, and explore the theoretical adequacy of the categories (Charmaz, 2014). Due to the nature of the constant comparative method and goal of theoretical sampling inherent in CGT (Charmaz, 2014), our line of inquiry evolved over the course of interviews. Some tentative categories were removed during this stage because they were not found to have theoretical centrality. For example, although engaging with allies was identified as a tentative category with theoretical plausibility, our ongoing analysis did not confirm its centrality to the emerging theory. Once the theoretical categories were saturated, meaning additional interviews and coding no longer lead to new insights or properties, the first author engaged in theoretical sorting and diagramming to develop the final theoretical model, in consultation with the second author.

Trustworthiness

Trustworthiness is paramount in most qualitative approaches. While member checking is utilized in some qualitative research, because many members of this authorship team identify as members of the research population, alternate measures of trustworthiness were deemed more appropriate: fairness, adequate data, and adequate interpretation (Morrow, 2005). Fairness requires the researcher to uncover and elevate multiple constructions regarding the research (Morrow, 2005). These data emanate from activists, with diverse social identities, whose activism reach ranges from local, low-impact actions to international, high-impact actions. The purposeful sampling approach undertaken allowed for multiple narratives to be captured and elevated, enhancing adequacy of the data. Fairness and adequate data are also demonstrated due to the non-confidential nature of the study, as participants’ real names are used, their activism ties are identified clearly herein, and their interviews are accessible by request. Adequate data was achieved by interacting with participants over longer periods of time and observing their interactions within their everyday contexts (Morrow, 2005). Multiple days were spent in community with nine of the 12 participants. For example, over the course of a weekend, Quess and the first author attended a training together, attended the same Black joy-focused Juneteenth celebration, and she witnessed and supported his spoken word poetry event. Importantly, the first author was not an outside observer, rather she was actively engaging in BLM activism in multiple roles and spheres before, during, and after the study was being conducted. Detailed field notes were kept throughout the duration of the study, including these periods of prolonged engagement with participants. Adequate interpretation is evidenced through our team-based co-analysis, where members memoed after every coding session. The process was rigorous, and the memos and field notes served as an audit trail. Adequate interpretation was also facilitated through a reflexive exploration of subjectivities (see Table Two; Morrow, 2005). Although additional social locations and biases were explicitly named and explored by the research team and explicated in the dissertation, the table reflects the positionalities requiring the greatest consideration during the study.

Table 2.

Positionality of Researchers Analyzing Participant Narratives.

| Team Member | Salient Identities | Key Assumptions, Biases, or Blindspots | Methods Used to Account for Key Assumptions, Biases, and Blindspots |

|---|---|---|---|

| First Author | Black, cisgender woman, queer/bisexual, able-bodied, Counseling Psychology Assistant Professor | Deep and personal desire for Black liberation from intersectional framework; bias against traditionally masculine, straight, cisgender men and bias toward Black queer femmes | Recruited racially diverse research team with varied approaches and commitments to Black liberation for increased accountability, explicitly named biases to team, used memoing and consultation to ensure all participant narratives were analyzed and integrated to a similar extent |

| Third Author | White, bisexual, cisgender woman, Counseling Psychology Doctoral Candidate | White privilege led to blindspots around the reality of anti-Black racism and racial trauma in its many forms as described by participants | Regularly sought consultation throughout process to help recognize the privilege she held and enacted, researched historical references to further understand the participants’ narratives |

| Fourth Author | Bi-racial, light-skinned, cisgender woman, straight, able-bodied, immigrant, Counseling Psychology Doctoral Candidate | Limited ability to see the context, reality, and history associated with the Black participants’ narratives due to own race | Brought experience in Black racial justice work and qualitative research, used memoing and consultation to bolster understanding, encouraged challenges from team throughout analysis |

| Fifth Author | African American, cisgender woman, straight able-bodied, Counseling Psychology Doctoral Student | Desire for equality and liberation of Black people and other marginalized groups; bias against those who endorse and benefit from the ideology of whiteness and white supremacy | Used memoing to focus on the interviewees’ responses and check her biases, welcomed feedback about blindspots and biases |

| Sixth Author | Black, cisgender woman, Educational Psychology Doctoral Candidate | Desire to promote health and well-being of Black individuals and communities through addressing social determinants Minimal knowledge on activism and development of critical consciousness prior to involvement in the study |

Named biases to team and used memoing to check for biases in interpretation, consulted with other research team members to check for understanding of critical consciousness process, researched previous models of critical consciousness |

Results

Critical consciousness of anti-Black racism (CCABR) involves witnessing, processing, and responding to ABR, all in a critical and intersectional manner. Table 3 explicates the three core categories comprising CCABR, their subcategories, and their processes. Broadly, Witnessing ABR centers on the processes associated with initial exposure to racism. Processing ABR is about the personal growth and development that transforms ABR exposure to a more critical awareness and increases efficacy to act on their awareness of racism. Finally, Acting Critically Against ABR is a process of engaging in sociopolitical action in an intersectional manner with the intention of facilitating Black liberation.

Table 3.

Categories and Processes in the Development of Critical Consciousness of Anti-Black Racism (ABR).

| Category | Subcategories | Processes |

|---|---|---|

| Experiencing Racial Trauma | Experiencing a wide range of psychological and social outcomes as a result of witnessing ABR. |

|

| Behavioral Growth | Finding ways to cope with the personal experience of racial trauma. Becoming connected to people and settings that will fill gaps in one’s development as a racial justice activist. | |

| Acting Critically Against ABR | Utilizing Black Racial Justice Activist Approaches to Activism |

Practicing context-specific, systemic, and intersectional approaches to prevent or resist ABR and racial trauma. |

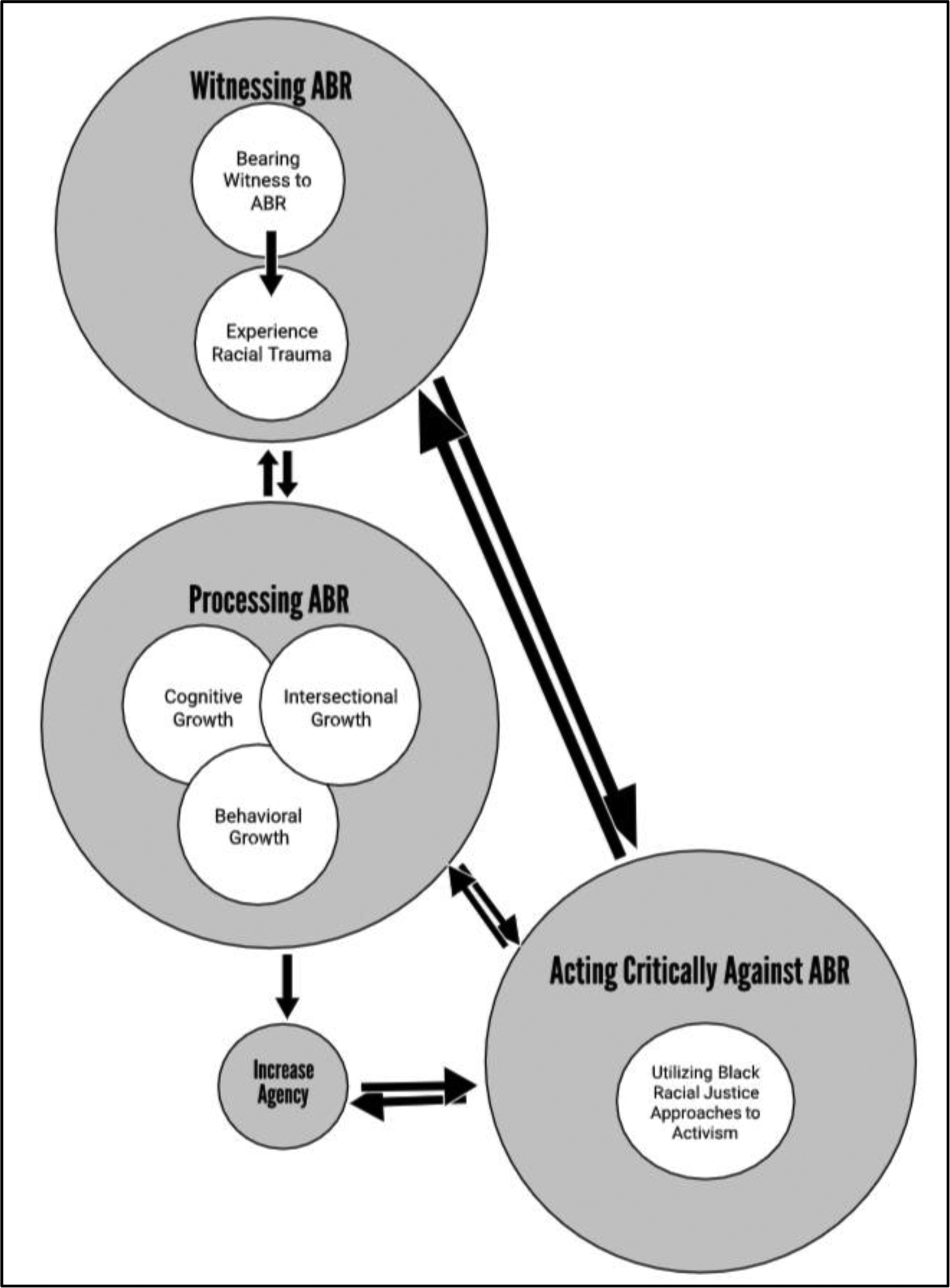

Participants begin CCABR development at different places based on their social locations and contexts. For example, Michelle’s father nicknamed her “Little Angela Davis” and exposed her to knowledge about how people resist racism (a Cognitive Growth process) before she had her first experiences Witnessing ABR in school as a young girl herself. Thus, CCABR development is non-linear and the order illustrated in Figure 1 represents the order that, from our co-analysis, allowed participants to build upon prior processes most effectively.

Figure 1.

Critical consciousness of anti-Black racism (ABR) model.

In our model, CCABR development begins with Bearing Witness to ABR, which leads to Experiencing Racial Trauma. After Witnessing ABR, participants would either work through it – by moving through specific Cognitive Growth, Intersectional Growth, and Behavioral Growth processes – or they would immediately respond to it by Acting Critically Against ABR. Critical actions were those done Utilizing Black Racial Justice Approaches to Activism. The model is cyclical and fluid. For example, Processing ABR facilitates agency, increased agency facilitates critical actions, as processing continues agency increases again and the cycle continues on. At any moment in CCABR development, Witnessing ABR can reoccur. Elena illuminates the fluidity of the process, noting “Nothing is linear at all…it’s, like, more a context that evolves.”

Witnessing Anti-Black Racism

Witnessing ABR provided participants with a critical lens to view ABR (Bearing Witness to ABR) and a psychosocial experience to associate with it (Experiencing Racial Trauma).

Bearing Witness to ABR.

Bearing Witness to ABR involves witnessing (e.g., hearing, seeing, experiencing) ABR and making a personal connection to that experience. Participants bore witness to ABR that was directly perpetuated against them, as well as through stories told to them. Participants bore witness to ABR early in life and repeatedly. Laina explained that at age five she faced overt racism: “The first day I got on the bus I was called a nigger and people started throwing things at me.” Michael shared:

I have always been a geek, but a cool geek. I used to wear blazers…carry a briefcase. And I had an art teacher who…said that I come to class and I open up my brief case like I have drugs or something in it. I am like “okay, I am in honors classes, doing well and the assumption was I must do drugs because I am a Black student in a school.”

Michael bore witness by actively making connections between his actual identity (e.g., geek) and his perceived identity (e.g., drug user) in the face of this experience of ABR. Participants also bore witness indirectly. Aaron bore witness early through his grandmother’s storytelling:

[Granny’s] talking about what’s going on and why this happens and why this doesn’t happen. And it’s, “because White folks don’t like this or that” and, “they’re not gonna let a Black man do this or that.” So, we hear it so constant. We realize, okay, this is something that we need to be aware of.

Aaron discussed how his grandmother’s stories helped him when he was later criminalized at a candy store by a White security guard. He concluded: “That’s when you realize, he’s White. I’m Black. Granny told me. There it is.” Bearing witness was a common and formative process.

Experiencing Racial Trauma.

Participants described Experiencing Racial Trauma related to their direct and vicarious experiences of Bearing Witness to ABR.

Psychological Processes.

Participants described an awareness of the chronic cognitive and emotional burden of overt and covert forms of ABR. The main psychological processes included internalizing ABR and feeling anxious and traumatized, which were associated with feelings of shame, anger, sadness, exhaustion, and disempowerment. Participants reported symptoms of anxiety (e.g., worry, hypervigilance, fear) and trauma (e.g., mistrust, nightmares, irritability) and expected other Black people to suffer in a similar manner. Geo reflected on her experience of “paranoia:”

All Black people at some point… live in this state of paranoia where you feel like you’re giving this too much attention. You don’t know if this is real. Like is this really happening?… It’s damaging to constantly have to overthink and overcompensate.

Participants described anxiousness about premature death and imprisonment. They reported living in fear, expected to die prematurely, anticipated being the target of police surveillance, and foresaw themselves experiencing imprisonment. Michelle stated, “at any point, somebody is going to have a problem with me when I wake up. And, on several levels, there are various justifications for my death.” Elena spoke candidly about the fear of imprisonment, sharing, “I always felt like, at some point, I would be in prison. I don’t know why it came. It was kind of like, ‘one day, it will happen.’ And it’s a fear that I’ve been walking with all my life.”

Social Processes.

The social aspects of racial trauma delineated by participants include lacking safety, experiencing isolation, and having relationships weakened or severed. The absence of safety was a constant in the lives of participants, from within their own neighborhoods, to their school and work settings, to their observance of broader systems. Michelle used the metaphor of war to describe her perpetual sense of unsafety stating, “Every day we wake up we feel like we’re in this war zone…I feel like I am at war every single day.”

Participants also reported existing in spaces where they regularly felt isolated, rejected, resented, reduced to a stereotype, and ostracized based on their race. Feelings of abandonment, lack of belongingness, loneliness, invisibility, disconnection, and vulnerability were common. Participants often described feeling sad as a result of the isolation and articulated their need for social support. Micah disclosed about the passing of a Black colleague who experienced isolation and reflected on his own isolation:

There was one other Black faculty member…Maxine was just a gift and…a fighter… I knew her passing was because of, I felt, some system things that were done in psychology that just hurt her to her heart… And so, I watched her die alone. She was the only. And I then became the next only.

The experiences of racial trauma described by participants often had relational costs. Participants described having friends, family, and colleagues who allowed or enacted ABR in their presence and resulted in the loss of a previously positive connection. Laina shared about how ABR shaped her past and current connection to her White adoptive parents.

Even to this day…I don’t have a very good relationship with my family…I remember I had…[read] Huckleberry Finn and every time the teacher would say the word nigger, he’d look at me…and I said, “can you tell this teacher not to do that?”…My mom: “Oh, well that’s just a book and that’s history.” And she wouldn’t do it.

Experiencing racial trauma occurred after Bearing Witness to ABR both directly and indirectly.

Processing ABR

Participants engaged in several processes that helped them to recognize ABR at a systemic level (Cognitive Growth), deepen their intersectional awareness (Intersectional Growth), and increase their capacity for coping with and resisting ABR (Behavioral Growth).

Cognitive Growth.

Participants experienced cognitive growth by increasing their awareness and knowledge of ABR as a systemic, versus simply interpersonal, phenomenon. For example, Michael shared how his experience talking to Black friends enrolled in graduate programs helped them recognize ABR “was something larger and systemic, in different types of programs as well.” Participants processed the systemic nature of ABR, critically reflected on their experience, and made personal and historical connections.

Participants valued history and developed a practice of making historical connections as they analyzed their environments and experiences. They described the importance of understanding their ancestral history, the history salient to their ethnoracial group, as well as U.S. and world history. Geo found her ancestral ties to Garifuna people who resisted slavery “powerful” and Micah reflected on the importance of learning about “catalyst moments” in Black history more broadly.

Intersectional Growth.

Participants shared narratives about how they deepened their intersectional self-awareness, particularly with respect to their Black, religious and/or spiritual, gender and sexual identities. The process involves beginning to recognize difference, learning one’s positions of privilege and oppression, considering them in context, and owning them.

Understanding Blackness.

Exposure to different performances of Blackness provided participants opportunities to analyze the systemic nature of ABR, their own social locations, and also the diversity of Blackness. Aaron described how traveling away from his hometown helped him recognize differences among Black people across the U.S. and motivated him to “bring the best” to his community. Similarly, Quess notes “We go into the hood and we find out, especially in…New Orleans, this is a very educated populous. Motherfuckers have never been granted access to say what they know in public, but Black people be knowing some shit” (emphasis added). Exposure often enhanced awareness of ABR and racial pride among participants.

Understanding religion and spirituality.

Participants also spoke in depth about their processes of understanding religion and spirituality in their journey toward CCABR development. Many disclosed Christian upbringings, yet they overwhelmingly identified as spiritual and non-religious in the interview. Consistent among their narratives of religious and spiritual exploration was a discussion of the importance of understanding (1) the connection between Christianity and White supremacy (particularly violence against POCI throughout history) and (2) the tendency for religion to facilitate passivity among Black people as opposed to critical action in response to their oppression. Elena and Aaron illustrate these perspectives.

Christianity, for me, is not getting away from the Black Code…a code of law of how to punish anybody who practices…a religion that is not Catholic or Christian. That’s what allowed lynching…Practicing Christianity is perpetuating that…I can’t do it.

-Elena

Many of us attack issues with the best heart and we’ll use a religious platform to get that done, which immediately alienates a lot of those who were trying to help…We have a part of us who need to be fighting, who say, “All right. I’m gonna pray about it.”

-Aaron

Alternately, some participants noted positive attributes of religion (e.g., sense of community, protectiveness for youth).

Understanding gender and sexuality.

Gender and sexuality were two final areas of intersectional growth important to CCABR development. Participants described gaining a deeper understanding of patriarchy and learning from gender expansive modeling when available to them. They recognized the toxicity of masculine norms and male privilege. Quess, for example, described how he was impacted by misogynistic messaging in popular hip-hop. He stated, “I had to heal and recover from being taught, ‘bitches ain’t shit but hoes and tricks’ and everything that [the rapper] Biggie gave me. I had to recover from those things.” Participants described breaking away from cultural gender norms by questioning and acknowledging the fluidity of sexuality, learning about sexualities, coming to voice about sexual desires, and expanding their social circles to be inclusive of diverse presentations of gender and sexuality. For example, Lamin notes, “I…battle with my girlfriend right now because I am a straight Black male, but I look forward to … pride festival. I’ve been to pride here in Lexington [Kentucky and] pride New York.” Participants often committed to a continual pursuit of intersectional growth. Lauren summarized this commitment, stating, “As a Black woman I have to push myself to try harder. There’s all types of cultures …that I don’t get…It’s partially my job…to have an awareness to challenge myself… you don’t stop. You’re on a treadmill. I need to be sweating.”

Behavioral Growth.

Participants described two important behavioral growth processes: coping with racial trauma and filling gaps to increase agency as an activist.

Coping with racial trauma.

Participants often coped by distancing themselves from Whiteness. Participants explained how they would experience racial trauma and, subsequently, begin to distrust White people. They distanced themselves by disbelieving, becoming ambivalent toward, increasing limits and boundaries with, disregarding, and/or renouncing Whiteness. Quess shared several instances of ABR perpetuated by White people and noted how he eventually coped through distancing, “That was the third offense. Three strikes you’re out! And after that I was just like, ‘You know what White people, I’m done.’” Additionally, some participants coped with racial trauma by performing respectability and acting unbothered by the experiences of racism. They resisted emotionality, restraining themselves from showing a response and disconnecting from feelings. Michael highlights the coping potential in respectability. He notes:

Even when I had teachers in…school who may not have believed in what or who I am as a student, I would still say “thank you mister so and so or misses so and so.” I would tune out that person as a person of authority… I would do my work and get over it.

For Michael, coping with ABR meant performing respectability to matriculate successfully.

Self- and collective care was also recognized as key to coping with racial trauma. Elena noted, “If I don’t take care of myself, I cannot take care of others.” The self-care coping behaviors participants undertook often involved spirituality and art (sometimes combined). Micah shared, “I have a singing bowl and a set of prayer beads by my bed that I often have to use when I wake up with dreams and nightmares.” Participants also discussed how their emotional reactions to racial trauma motivated them to seek connection and build a community with others. Social support was sought from family, friends, community members, elders, Black institutions, and professional healers. Lauren illustrates the impact of this form of collective care, noting, “Being able to have a place…that’s safe and cooking stuff for ourselves and understanding what soul food means, [that it] is about togetherness and love and connectivity…Feeling connected with folks, I get validated internally, and that pushes me.”

Filling gaps to increase agency as an activist.

Participants filled gaps in their development as Black racial justice activists by making connections with settings and people that would increase their self-knowledge, systemic and cultural awareness, and ability to act against ABR. These settings allowed participants to gain education related to social justice activism (e.g., direct action tactics), the system of White supremacy, and the diversity of ways in which ABR causes harm. Classes, academic programs, conferences, and community-based programs centered on Black people, Black history, or Black culture were growth-promoting settings for participants. Black cultural spaces also helped fill specific gaps participants had in their ability to critically act against ABR. Such spaces could be stable (e.g., barber shops, Black Twitter), temporary (e.g., an impromptu social gathering), or transient in form, such as campaigns that crossed physical and virtual platforms (e.g., #BlackGirlMagic, #BlackLivesMatter). Elena illustrates how a conference helped her understand the Black experience on a collective level:

I would go to conferences…about Black realities, and I would be in the room full of other Black people who would say, “Mm-hmm (affirmative),” at the same times as me. And it’s like, “Okay, we share this together.” “Okay, you live that, too. Oh, shit, this is real.”.

Making connections allowed participants to enhance their sense of self as Black racial justice activists and develop community around that identity. Having family and friends who were further in their CCABR development and already engaging in liberatory actions often helped participants to gain entry into spaces where Black-focused consciousness raising, organizing, and activism occurred. Aaron highlights how a church setting, connected and conscious family members, an invitation to an active community organization merged to increase his CCABR. He shared his experience at his first racial injustice rally or meeting in 1988:

The school board here in Rockford was being sued for racial discrimination. There was a group called People Who Care and they were holding meetings …I was in gifted programs. So, that was one of the topics of discussion: how the gifted program was discriminating against Black people. And I’m in there, like, ‘I’m in gifted. How were they doing me wrong?’…My eyes opened to realize, okay there are only two or three of you in the class…And the People Who Cared basically exposed that. So, at [age 7 or 8] is when it was like… this isn’t right…My Uncle Robert took me to the meeting. He knew [an organizer] and me being involved in gifted hit home for him.

Participants would learn, question, clarify their values, witness different approaches for responding to ABR, and begin to build or expand upon their community in these settings. Some of the information repeatedly seen as important to participants in this process included learning social justice terms and Black and activist values and approaches. Geo describes how academic settings, non-profit community programming, and a radical supervisor exposed her to concepts and facilitated her practice as an activist. She described her first experiences of activism with:

…this super awesome supervisor… she introduce[d] this idea of systems and structures…So what we were trying to do with the city was find a way to buy the [plots of land where buildings were burned in the Bronx] and use it for farming because now there are food deserts in the south Bronx. So that’s where I learned about all of these different social justice terms and all of these things that I was seeing …It was a summer program…They would partner you with a non-profit in the Bronx, and you would work there a few days out the week. Then take a class on something like civil engagement.

Through Processing ABR in these three core ways, participants’ sense of self and collective agency related to resisting ABR increased.

Acting Critically Against ABR

Acting Critically Against ABR is a category focused on specific approaches, or the intentional processes, participants used in response to ABR at any point after Witnessing ABR and understanding it as a systemic problem. Utilizing Black Racial Justice Activist Approaches to Activism describes the nine approaches they took when engaging in this work. Within these approaches, described below, a Black Liberation Work Compendium was developed (see Table 4) to provide a taxonomy for the nine types of activism these participants engaged in. Whereas the approaches were processes that created the framework for action, the specific actions are exemplars of what can be done within the framework.

Table 4.

Black Liberation Work Compendium.

| Subcategory | Definitional Properties | Representative Quote |

|---|---|---|

| Storying survival | Sharing stories, critiques, testimonies, or otherwise advocating about ABR for the purpose of facilitating Black liberation | “I’m going to tell it to you so well that you don’t forget it. And I know someone who looks like me probably went through something very similar. So don’t think that this exists in a silo.” -Geo |

| Artivism | Using creative arts in the interest of facilitating Black liberation | “We created this play called ‘Voices of the Back of the Class’ talking all about miseducation…We used Lies My Teacher Told Me as the text and then we create skits and do story circles off of that” -Quess |

| Physical resistance | Putting one’s body at risk of danger in order to protect, liberate, or affirm Black people | “I stood before a tank, the National Guard coming down our street and I just stood before the tank and I said ‘you’re not coming down my street…I was 10” -Micah |

| Organizing | Developing goals, identifying outcomes, and determining approaches for Black liberation; involves leading, organizing, and developing interventions | “With my social media background, I have software that I can pull up, set up different feeds and stuff. …so I was essentially, I was like, ‘okay, St. Louis PD is moving on this bridge. If you on the ground right there, you need to move.’” -Lamin |

| Teaching | Educating others and encouraging them to constantly learn more about ABR and Black liberation | “Now it’s my job to go into [student organizations] … and calling them out, and they know it’s happening but it’s really being like ‘get over your white guilt and find ways to include people.’” -Geo |

| Coalition-building | Developing, maximizing, and sustaining relationships to promote Black liberation | “I’m particularly excited about…doing law enforcement trainings related to multicultural awareness, diversity, inclusion.” -Lauren |

| Modeling/Mentoring | One-on-one contact with another Black person to proactively affirm, support, and increase Black wellness | “…showing up to activities that [Black undergraduates] were putting on campus and really letting them know…I’m interested in seeing you succeed.” -Erica |

| Scholar-activism | Engaging in activism informed by scholarship and/or contributing to scholarship informed by activism that is focused on Black liberation | “I really got involved in research and realized that majority of research is not inclusive of the everyday experiences of Black kids and Black males in particular.” -Michael |

| Spacemaking | Intentionally creating physical or virtual spaces for Black people to convene heal, organize, and/or celebrate | “What we do is create space where we can talk about Blackness…or create context where we can meet and have activities together” -Elena |

Utilizing Black Racial Justice Activist Approaches to Activism

Utilizing Black Racial Justice Activist Approaches to Activism refers to the way participants engaged in activism. These approaches were often informed by prior CCABR development processes. For example, contextualizing was an approach participants could more readily apply if they had previously deepened their historical knowledge. Each of the nine approaches are described below.

Having urgency.

Participants put forth effort toward Black liberation in an urgent manner and believed that others should as well. Aaron highlights the importance of urgency sharing, “We can’t be slow to reaction at it, to where a Black life is taken and then, all of a sudden, we move. We have to have a plan of action before our lives are lost…We have to go, now.” Participants like Aaron articulated their value of immediate, preplanned action as a response to injustice. They reflected a high degree of responsiveness to ABR through critical action. While they were committed to urgent action, they were not simply reactive. Their actions were explicitly tied to Black liberation. They believed actions should be enacted strategically, yet urgently. Elena’s narrative exemplifies urgent action:

We created an inspired by Black Lives Matter…because someone was killed recently by police and we met their…friends, [who] organized a march. And then …we decided to meet and talk about it, and then that became, like, ‘Okay, let’s do something about this.”

In this narrative, an incident occurred inspiring the activists to respond urgently. However, they analyzed the situation and met to plan a strategic response that could still be executed rapidly.

Being self-reflective.

This sample was self-reflective while doing different forms of activism. They recognized their limitations, when efficacy was low, and when help was needed. Participants were conscientious about how others might perceive them and tried to stay attuned to when they made a misstep that could potentially harm others. Self-reflectiveness enabled them to take ownership over their actions and improve their activism and relationships in the process. Participants also thought through the meaning and impact of their commitment to activism. They were explicit about the fact that their engagement in activism was, sometimes, taken on as an intentional attempt to heal from the pain of ABR. Elena’s self-reflectiveness highlighted the cost (loss of energy) of her actions and also underscored the personal benefit she received (personal emancipation) from doing activism. She shared:

If racism didn’t happen, what would I be? Cause so much of my energy is spent in this. Would I be at the same level, or would I be further, more? Or would I be never emancipated, because I emancipated through this? I don’t know, but those are questions that I’m asking myself.

Self-reflectiveness also allowed participants to pivot in their activism pursuits while in process.

Specifying focus.

Participants noted the importance of specifying their focus on particular manifestations of ABR and/or a community that is contending with ABR when engaged in Black racial justice work. Participants’ decision-making processes regarding their foci varied based on their own identities, contexts, skills, and comfort in different roles and positions. For example, Lamin describes how his skills informed his focus as an activist:

I have a political background also, so I have friends who are on the city council and people in the police department. So where can I pull from those resources? Also, I have a…public relations background, so how can we use media effectively?

Michelle specified her focus, both in terms of the community she hoped to impact and the aspect of ABR that she wants to change. She shared:

What comes to me is the radicalness of taking care of what you are directly responsible for and that is your household. Training people in your homes. Read books, get the counseling, talk to your network, get your people involved…have a conversation. …With Brown and Healthy, the tagline is “Change the narrative, change the world.”

For Michelle, taking care of her family and altering the narrative around Black wellness was important. Specifying focus allowed participants to better plan their efforts and assess impact.

Being actively intersectional.

Being actively intersectional means that while one is working toward Black liberation they attend to dynamics of power, privilege, and oppression in both planning for their activism work and implementing their activism work. Participants sought to be mindful of privilege, leveraging their own when beneficial to the cause and working to expand the power of others experiencing oppression. Aaron shared:

The focus of S.A.F.E. Rockford’s website… which compiles a lot of the people, organizations, community centers, and positive events for families. It’s pretty useful,…to keep kids away from negative things. So, in just realizing the need for that, you also see the need for…if I create a website, how does a parent who doesn’t have internet get to that? Well, there’s a program at Rockford that gives internet to every student in public school. But if you don’t have any awareness of that program, you’re missing out on that internet that’s gonna lead you to my website that’s gonna lead your kids to a better life.

Aaron realized access would be an issue for some low-income members of the community he sought to reach and made it part of his mission to increase community awareness about a solution. Elena offered another example of being actively intersectional doing activism focused on people who were incarcerated. She shared:

I learned a lot about that life…One thing that I discovered is that I never lived incarceration, so there’s still my gaze of my interpretation…I was working so hard on…not judging, but even though I don’t want to, there are things that I don’t know about that life. I wanted that project to eventually become led by people who lived that reality.

For Elena, she used her privilege to establish relationships and initiate a project that would amplify the voices of people who are incarcerated. Being actively intersectional, however, she recognized the need to then relinquish leadership (e.g., privilege) to the people most directly impacted by incarceration. Participants tended to value people our society traditionally devalues, and they reduced power differentials by being actively intersectional in their activism.

Being resourceful.

Doing activism required time, energy, money, and resources. Participants developed methods that would help ensure they could afford to engage in activism. Despite financial concerns, participants found ways to fund their activism-related needs and allow the time, energy, and other resources required. For example, some of the costs of activism included time away from primary jobs, housing when traveling to a protest or Black liberation training, a workforce, space for Black wellness events, or materials for artivism projects.

Participants often relied on their social networks to support their activism efforts. They recognized that activism required, as Quess noted, “many hands, light work.” By utilizing “many hands,” they lightened their load and resourced their activism work. Resourcefulness also meant finding ways to merge one’s activism interests with their professional responsibilities, because they needed to sustain their incomes. For Michael, being resourceful meant using his position as an Associate Provost to engage in Black racial justice work. He detailed:

When I first got there, they would get an excel spreadsheet of all the applicants…They would have GRE score, name, race, school, publication, GPA, and all that type of stuff. I would go down by the race category and be like okay who are all the Black students who applied?… I would say, okay so this person needs to be interviewed…I might work with this person; this person would be good for you. It is to make sure that other Black students would be at least reviewed, if you will, and considered for admission.

For him, being resourceful meant utilizing his time and roles so that he was working toward Black liberation while maintaining the standard commitments of his profession. Participants who engaged in activism outside of their primary jobs had to be resourceful as well. Sometimes this meant adding a formal structure to their activism efforts. For Michelle, this meant turning her movement from a hashtag into an organization. She shared:

We had to become an organization, so that we could get the grant funding and things to push the programs. You can’t just exist in the nether regions. It has to exist, and it has to be a clear and defined rule, a clear and defined mission, and a clear and defined person who you can come to if you got some issues with Brown and Healthy. …It will not be adapted or taken by other people as the forefront of whatever. It is, yes, a movement but it is a movement with a clear base and with a clear structure.

Being resourceful was imperative in sustaining and maintaining the integrity of activism among participants like Michelle.

Contextualizing.

Participants believed their activism efforts should be tailored specifically to their environmental contexts. They chose how to respond to ABR based on the setting they were in, the community they were doing activism with and for, and what the moment called for. By contextualizing, participants garnered support, tailored their actions to their specific targets, and made meaningful impacts in their communities. Quess narrated:

We all kinda rock stars in the community for whatever things that we do. So, we knew between the ten of us we could get people. We did not know it’d be 300 people. That’s the biggest action we’ve ever had. That’s a big number in New Orleans all gathered. And I made a suggestion that night, “Yo, let’s go to Lee Circle [location of a confederate monument]…We gone highlight you know what is going on.” I was hip to that because Malcolm and Leon who were old school activists had been doing that work for decades. And I went to one of they teachings like five, six years prior. When we highlighted that, that began the work of uh Take ‘Em Down really. Because we all made asks that day. We had three different petitions went out, and one of them was to have Lee Circle taken down.

In this example, Quess highlights many forms of contextualizing. First, understanding his social support network and each person’s potential reach when promoting a racial justice event was one context he considered. Second, in determining what would constitute a success, he contextualized based on contemporary history of local social actions. Third, he suggested an action centered on an environmental context where White supremacist symbols were present.

Being persistent.

Being persistent means being resilient and not giving up in the face of ABR and challenges to activism. Participants continued their activism despite pressures, struggles, barriers to wellness, and risks. When relationships, actions, or outcomes did not go as they hoped, participants were persistent and remained committed to their goals irrespective of the time and work it took to reach that end. For example, Erica highlighted being persistent as she described her struggles to work with people earlier in their CCABR development.

Some of the things that can happen as folks, as they’re not as passionate as you are or if they’re not being involved in the same way that you are, then you can get frustrated. And you can say “Well you don’t really understand, you’re not really standing with us, you must be against us.” It can create this environment that doesn’t really need to be created. It’s just, again, a continued understanding, a respect for what’s going on…a continued presence and just saying ‘you know I’m going to maintain this presence.’ If you think about love, a true demonstration of love is being with someone through the good and the bad as they develop, as they change.

Erica’s love ethic helped her to be persistent and maintain a presence with Black people who were not committed or acting on behalf of Black racial justice. However, Geo offered an alternate narrative where she stopped her activism due to barriers to wellness. “People drop off because it’s too much. It’s really heavy… I’ve just tapped out for a year and was like I just need not engage in anything and just figure out what’s going on internally”

The types of activism participants engaged in sometimes required significant time and effort, especially to make a large impact. Whether their Black racial justice efforts were organizing a symposium, changing university policy, organizing a citywide demonstration or protest, or putting on a play, their activism took persistent effort to make it happen. Lamin describes the persistence required to garner support for marches in Lexington, KY that would be in solidarity with Black Lives Matter and the death of Michael Brown in Ferguson, MO. He noted, “I remember, we came back from Ferguson two years ago. It took us a few months to even get, we did get a nice 100 or 300 downtown, but that took months.” Participants emphasized persistent effort was required to make broad, systemic change.

Maintaining future orientation.

Maintaining future orientation involved working to ensure efforts toward Black liberation were sustainable. Activists who maintained future orientation were visionaries interested in facilitating long-term systemic change in the interest of Black wellness. Participants grappled with how to sustain the movement and tended to be focused on quality over quantity when engaging in activism. For example, Laina recognized the need for ongoing support for the women of Color she was spacemaking. She stated:

I’m seeing how it works. The networking and the community that’s being built…things don’t end after this one day…and knowing that you will have to continue on with this. Knowing that one symposium is not going to be enough or one hang-out or meet-up is not enough. That there’s always going to be more women that should be involved. And … negative issues that will bring them, like they will need to talk about.

Laina and other participants engaged in activism, assessed its impact, and – if it met their Black wellness goals – then strategized methods for ensuring it could be maintained in the future.

Acting Critically Against ABR represented the “what” (Black Liberation Work Compendium) and the “how” (Utilizing Black Racial Justice Approaches to Activism) of preventing and resisting racial trauma. The activists in this study co-constructed a process of developing CCABR which moved them from Witnessing ABR, to Processing ABR, to Acting Critically Against ABR; ultimately facilitating Black liberation.

Discussion

The CCABR model is the first to explore the processes involved in developing critical consciousness related to a form of oppression: anti-Black racism. This empirical model, grounded in the core values of counseling psychology (Packard, 2009), suggests a complex, non-linear, yet specific process that promotes resistance and prevention of racial trauma. Developing CCABR started with (1) witnessing ABR and experiencing racial trauma, (2) required the development of cognitive, intersectional and behavioral growth in order to process ABR and develop a sense of agency, and (3) resulted in participants engaging in activism against ABR through an intersectional approach. The CCABR model illustrates how the three primary processes influence and interact with each other to propel participants towards critical action.

Extant research on critical consciousness more broadly points to several benefits of developing this capacity. Some benefits of developing a general sense of critical consciousness include reduced disease progression for Black women with HIV (Kelso et al., 2014), protection against mental health problems among Black men (Zimmerman, Ramirez-Valles, Zapert, & Maton, 1999), increased self-esteem among high school students (Christens & Peterson, 2012), and intentions to persist in college for White and Hispanic students (Cadenas, Bernstein, & Tracey, 2018). Given that positive outcomes resulted from the cultivation of a non-specific form of critical consciousness development, the potential benefits for Black individuals and communities through CCABR development processes appears promising.

There are countless studies that make plain the prevalence and deleterious impact of racism (Carter, 2007; Pieterse et al., 2012), consistent with findings in the Witnessing ABR category. Further, the CCABR model also suggests that bearing witness to ABR and experiencing racial trauma has utility in that, when it is followed by the steps delineated in Processing ABR, it can facilitate coping, healing, and system-focused liberatory action.

Witnessing ABR provided participants with a critical lens to view ABR. Participants understood ABR and its consequences intimately and had this personal level data to build from as they moved toward processing and acting. These findings align with the concept of the wounded healer archetype in psychology (Zerubavel & Wright, 2012). The wounded healer has a lens through which they can empathize, connect, understand, and help heal based on their history of being similarly wounded (Zerubavel & Wright, 2012). Like participants who co-constructed this theory, their personal experience of pain can lead to their helping larger numbers of people struggling with similar stressors. Alternatively, there is the potential that engaging in the work as one who has been wounded can lead to chronic dysfunction or relapse and an inability to be helpful to others (Zerubavel & Wright, 2012). Based on this model, it appears that without processing ABR, Black people may internalize racism, suffer from the experiences of racial trauma outlined by participants, and become complicit in perpetuating racism themselves. Just as there are processes that facilitate posttraumatic growth for wounded healers (Zerubavel & Wright, 2012), these findings provide a model for healing for Black people who experience racial trauma. When individuals have found methods of processing ABR – as clearly outlined herein – then witnessing ABR can be informative and a catalyst to action. Processing ABR may represent an important division point between Black people who experience and possess a critical awareness of ABR but do not engage in Black racial justice activism and those who do.

Notably, Processing ABR was easier for some participants in the sample than others. For example, some participants were embedded in contexts where processing cognitively, intersectionally, and behaviorally were already common and could be more seamlessly enhanced. Many had educational or social capital privileges that facilitated their development as activists. For example, Lamin and Michelle were raised in homes where Black history was commonly discussed and resources for expanding awareness were readily accessible. However, other participants had to find alternate means of coping, connecting, and expanding their awareness in order to increase their agency as activists. Empirical studies have shown that those who development a strong positive racial identity are more likely to effectively prepare, process, and develop appropriate responses to racism and discrimination (Cross & Strauss, 1998; Sellers et al., 2003, 2006), thus making them equipped to engage in critical action. For individuals who regularly witness ABR and have fewer supports for processing, the widely recognizable Black Lives Matter movement offered the growth mechanisms that may have been absent or subpar in their lives. This suggests that large-scale interventions like BLM can facilitate the critical consciousness development of diverse Black people who are inevitably experiencing racial trauma.

Findings from this study suggest that deepening intersectional self-awareness is what facilitates the commitment to a collective and inclusive vision of Black liberation. The process involved learning one’s positions of privilege and oppression, considering them in context, and owning them. Participants acknowledged the way their skin tone, socioeconomic class, gender presentation, etc. positioned them differently in the social hierarchy. This broadened their perspectives on various social identities and led participants to adopt an intersectional analytic frame as they considered the many ways ABR manifests and impacts Black communities. Notably, the BLM organization was founded by three Black women, two whom identify as queer (Sands, 2017). Several perceived leaders of the movement during the time of the study identified as queer (Sands, 2017) as well and/or adhered to a “queer Black feminist” agenda for liberation (Carruthers, 2018). The combination of moving through the processes of intersectional growth and engaging in Black liberation work under this queer Black feminist agenda likely worked in tandem to solidify participants’ commitment to liberation for all Black people. The queer Black feminist approach is different than prior movements for Black liberation that required or relied on maintaining politics of respectability, centering cisgender heterosexual Black men, and rendering invisible the needs and efforts of Black people who contend with multiple systems of oppression due to their social identities (Cohen & Jackson, 2016).

The findings associated with intersectional growth, though novel to critical consciousness research, also builds upon extant research on implicit attitudes (Gonsalkorale, Allen, Sherman, & Klauer, 2010; Gonzalez, Steele, & Baron, 2017). Studies on implicit racial bias have indicated that exposure (through indirect or direct contact) to out-group exemplars can reduce implicit biases (Gonsalkorale et al., 2010; Gonzalez et al., 2017). The activists interviewed for this study described being exposed to people with different identities and beliefs and increasing their empathy and collectivism afterwards. Exposure may not only reduce implicit bias through contact with exemplars, but for Black people who have experienced ABR, exposure to Black people who differ from them may reduce implicit biases and increase their commitment to an inclusive vision of Black liberation as well.

Although far from comprehensive, the Black Racial Justice Compendium offers a starting point for explicating types of Black activism engagement. Szymanski (2012) used an Involvement in Feminist Activism Scale and replaced the word “feminist” with “African American” to elucidate data on liberatory activities utilized by Black people. The current study offers support for Szymanski’s (2012) modified scale, as our participants endorsed nearly every behavior on the scale (e.g., organizing, mentoring). However, three of the most frequent activities endorsed by participants in this sample (storying survival, spacemaking, and artivism) are not accounted for in Szymanski’s (2012) scale. Furthermore, the current research adds to the existing literature by illuminating activities taken up by activists with intersectional values.

Importantly, our findings fill a void that exists on what Black activism is and how Black activism is enacted in the current sociopolitical climate. This study delineates participants who actively resisted ABR and seemingly prevented racial trauma. For example, through removing confederate monuments, Quess and his comrades with #TakeEmDownNOLA both resisted (in the fight to remove the monument) and prevented (when the removal efforts were successful) racial trauma for the community in New Orleans. Similarly, Michelle’s development of a culturally-specific health initiative affirming Black people (#BrownandHealthy) prevented the racial trauma symptoms of isolation and invisibility in Baltimore and beyond, instead promoting social connection and Black mental and physical wellness.

Implications for Counseling Psychology

Increasing Black people’s capacity to prevent and resist racial trauma is a worthy social justice cause aligned with our specialty discipline’s social justice, prevention, and strengths-and resilience-focused values (Pieterse et al., 2012; Vera & Speight, 2003; Watts, 2004). Although the findings from this study are delimited to Black individuals, they have applicability to non-Black people as well. Using data that derives from one population (e.g., Black activists) to inform and guide the actions of individuals of other races (e.g., psychologists, individuals who serve Black people) is a goal of diversity science (Plaut, 2010). With this understanding, an overarching implication from this study involves the need for counseling psychologists to assess their own CCABR development. After reviewing the implications for practice and research, the potential for CCABR self-assessment among counseling psychologists are addressed.

Implications for professional practice.

Intentional efforts toward promoting healing from racial trauma are needed (Helms, 2017). Based on the participants’ narratives, educators need to train future counseling psychologists to be aware of the prevalence of ABR and of racial trauma, so they can be more culturally mindful clinicians, researchers, classmates, and citizens. Training programs should ensure that clinical training includes meaningful opportunities for students to learn about assessment and treatment associated with racial trauma. Without proper training, emerging psychologists will constantly be at risk for ascribing individual diagnoses to systemic problems. Relatedly, practicing psychologists could encourage clients to share about their experiences developing CCABR. Creating space for clients to engage in storying survival around their experiences of ABR, and about their process of coming to awareness about Whiteness or acting critically in resistance of ABR, may represent a healing intervention. Integrating artivism may also bolster this exercise. When clients are storying survival in this way, psychologists could look for opportunities to emphasize historical connections and other contextual factors and assist individuals in naming the systems and processes of oppression at work. Creating space for storying survival may help to minimize Black clients’ tendency to internalize negative racial experiences, which can lead to feelings of anger, sadness, and/or anxiety. Trauma-Focused Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (Warfield, 2013), Narrative Therapy (Neville, 2017), Ethnopolitical Psychology (Comas-Diaz, 2007), and Radical Healing (French et al., 2019) may be good places to begin exploring these methods for therapists less acquainted with liberation-focused counseling methods and frameworks.

Implications for research.

The current study provides several implications for research. Participants in this study identified numerous racial trauma symptoms and went on to describe their engagement in activism as one outcome associated with that experience. Research on the extent to which activism engagement mitigates racial trauma symptom severity should be initiated. Research that leads to the development of racial trauma assessments (e.g., brief assessments, mobile applications) may be of particular use to activists and activist organizations. Quantitative and mixed method studies on exposure to ABR, engagement in Black activism, and racial trauma symptomatology could also help uncover strategies for improving wellness in the face of ABR. Additionally, intervention research examining the therapeutic efficacy of the strategies described in Acting Critically Against ABR may also be a next step for research.

Advancing intersectional self-awareness may also be a useful endeavor for educators, clinicians, and researchers. Students who have not been exposed to the diversity of Blackness would benefit from additional education on the intersections of identity outlined by this study’s participants. At minimum, counseling psychology trainees are expected to promote wellness with respect to individual and cultural diversity, commit to self-examination, and uphold professional ethics as they engage in research and clinical practice (Bieschke, 2009). Given these expectations, the findings on intersectional self-awareness may be useful for programs seeking to determine student readiness for work with Black clients or research involving Black participants. Since participants who identified as Black struggled to develop critical consciousness until they were exposed to the diversity of Blackness and grappled with their own areas of privilege and oppression across several social locations, we can surmise that this process will be critical for any trainee seeking to promote Black wellness through their role as a counseling psychologist. For students with less exposure to Blackness, it is especially important that this education be integrated into the training program. Goodman and colleagues (2015) warn against the use of standalone cultural immersion projects that lead to voyeurism and “othering” – an experience of racial trauma described by our participants – but suggest prolonged community engagement where students are embedded in diverse communities.

Self-Assessment of Counseling Psychologists’ CCABR.

Counseling psychologists may benefit from assessing where they are in the process of developing CCABR. A first step in assessing CCABR may involve reflecting on one’s own skills as it relates to recognizing ABR, both in their immediate contexts and across the systems in which they regularly engage. If a person has developed a capacity to bear witness to ABR, then determining their growth edges in the cognitive, intersectional, and behavioral realms may prove beneficial to their work. For example, the expansiveness, normalization, and constant evolution of Whiteness requires that individuals enhance their analysis skills (Cabrera, Watson, & Franklin, 2016). This might also involve exploring one’s capacity for recognizing historical context and making structural attributions when concerns involving Black people are raised (e.g., in clinical work, through media stories, research findings). Participants in this study suggest that enhancing critical thinking skills related to Whiteness, White supremacy, ABR, and social justice is an ongoing process that they are constantly working, “sweating,” to expand upon. While participants in the current study were all Black, Case (2012) found that for White people striving to practice antiracism, it similarly required ongoing self-evaluation and community support.

Strategies in the Black Liberation Work Compendium align with many counseling psychologists’ roles and responsibilities. For example, modeling/mentoring and teaching, as defined in this model, lend themselves nicely to counseling psychologists embedded in any system where Black people are found. Additionally, researchers can practice scholar-activism to promote Black wellness. Given the approaches to Black racial justice work delineated by participants, and their alignment with counseling psychology values and approaches (Hargons et al., 2017), counseling psychologists can not only assess their success at CCABR but strive toward being leaders as it relates to promoting Black wellness through CCABR.

Limitations

There are some limitations to the present study. The CCABR model was derived from the participants, research team, and the knowledge that these parties brought as a result of their positioning and the sociopolitical climate of the time. This co-construction is highly contextual, dynamic, and specific to one movement for Black liberation, and thus another team may have interpreted a different model of development. The participants’ stated commitment to Black liberation, combined with the non-confidential nature of the interview, may have influenced how they positioned themselves in their narratives. Additionally, although efforts were made to reduce power differentials, differences in class, education, gender and other axes of difference between the researchers and participants could have contributed to missed narratives and unasked or unanswered questions. Despite noted limitations, the measures of trustworthiness (e.g., prolonged engagement, co-analysis, memoing, non-confidentiality of data) ensured that data are rigorously collected and analyzed.

Conclusion