Abstract

Background:

Dry, itchy skin can lower quality of life (QoL) and aggravate skin diseases. Moisturizing skin care products can have beneficial effects on dry skin. However, the role of a daily skin care routine is understudied.

Objective:

To understand how daily skin care with a mild cleanser and moisturizer impacts skin health and patients’ QoL, in dry skin population.

Methods:

A randomized, investigator-blinded study of 52 participants with moderate to severe dry skin. The treatment group (n=39) used mild cleanser and moisturizer twice daily for two weeks whereas the control group (n=13) used mild cleanser without moisturizer. Total Clinical Score (TCS; erythema, scale and fissures), Visual Dryness Score (VDS) and subjective itch-related quality of life (ItchyQoL) were collected.

Results:

The treatment group showed significantly more improvement in TCS and VDS compared to the control group after two weeks. Among the three components of the ItchyQoL (symptoms, functioning, and emotions), symptom showed significantly greater improvement in the treatment compared to the control group. Over 80% of participants in the treatment group agreed that the regimen led to decrease in dryness/pruritus and improved skin texture.

Conclusions:

A consistent skin care regimen should be an integral component of management of dry skin.

Keywords: dry skin, xerosis, atopic dermatitis, pruritus, moisturizer, quality of life

Introduction

Dry skin is a very common condition characterized by a scaly and flaky appearance. Many factors can precipitate dry skin and if it worsens, there may be erythema and fissures (erythema craquele)[1]. Dry skin is oftentimes exacerbated by environmental factors such as frequent washing, use of harsh soaps or cleansers, central heating or air conditioning, and cold and dry weather, that contribute to loss of skin hydration[2, 3]. Dry skin can be presented as a symptom of various skin diseases (i.e. atopic dermatitis) or systemic diseases (i.e. uremic, hepatic) but also may present without underlying diseases (‘xerosis’), especially in the elderly population. Dry skin often accompanies pruritus which may lead to scratching that may increase the risk of infection and aggravate other skin diseases, as well as negatively impact a patient’s quality of life (QoL)[4]. A ‘dry skin cycle’ has been proposed for dry skin conditions to describe its induction and propagation[5]. In this model, dry skin is initiated by decreased water content in the stratum corneum and is further exacerbated by destruction of the normal barrier lipid lamellae during bathing[5]. Mild inflammatory hyperkeratosis is a key feature of dry skin that leads to defective keratinocyte differentiation, change in epidermal lipid profiles particularly in ceramide biology, loss of natural moisturizing factor (NMF) and reduced activity of desquamatory enzymes resulting in scaling[5]. Skin care products with predominantly moisturizing features and targeted for sensitive skin can have dramatic beneficial effects on dry skin and break the dry skin cycle[6–11]. However, the role of a daily skin care routine in dry skin has been understudied and under-utilized in medicine. In this study, we aimed to understand how daily skin care with a mild cleanser followed by a glycerin-rich moisturizing lotion impacts skin health and patients’ QoL, in a moderate to severe dry skin population.

Materials and methods

Study Design

This was a randomized, investigator-blinded, single-center study carried out in the Dermatology clinics at Johns Hopkins School of Medicine in Baltimore, Maryland between May and July which is late spring and early summer, in 2018. Study visits were performed at screening/enrollment day (7 days before baseline), baseline (day 1), and day 15. All participants provided written informed consent before enrolling in the study. This study was conducted in accordance with the ethical principles derived from Declaration of Helsinki and ICH Good Clinical Practices and was reviewed and approved by the Johns Hopkins Medicine Institutional Review Board (IRB00165140). This study was registered in clinicaltrials.gov as NCT03497130.

Prior to the start of the study, a randomization list was generated by a research staff independent of the study using variable block sizes of 4 and 8 and an allocation ratio of 3:1 (treatment vs. control) randomization scheme (https://www.sealedenvelope.com). The investigator who assessed patients’ skin condition was blinded until the study was completed.

Participants

Healthy volunteers aged 18 years and older who had moderate to severe dry skin were enrolled. Participants had to have clinically dry skin, corresponding to a score of at least 2 (moderate dryness) on the Visual Dryness Score (VDS) determined by a dermatologist on at least one of four extremities for inclusion at baseline. Participants who had been treated with systemic retinoids or steroids within the past month, treated with topical steroids or topical retinoids or other topical drugs within 2 weeks, used an investigational drug in the prior 30 days, and women who self-reported that they were pregnant or nursing were excluded. Participants who had systemic diseases (liver/biliary, renal, heart, infectious, malignant disease) or skin diseases (atopic dermatitis, psoriasis, ezema, urticaria) which might affect their involvement in the study were excluded. Participants were asked to refrain from swimming or hot tub use and limited to no more than two showers per day during the study.

Skin Regimen Application

Subjects refrained from using moisturizer for one week and switched from their normal cleanser to a mild cleanser (Dove Sensitive Skin®, Unilever) (washout phase) and then were randomized in a 3:1 ratio of treatment to control groups. The treatment group (n=39) continued to use the mild cleanser for daily body cleansing and then also applied a moisturizer (Vaseline Clinical Care Extremely Dry Skin Rescue Lotion®, Unilever) twice daily for two weeks, whereas the control group (n=13) continued to use the mild cleanser only without moisturizer. Subjects recorded their usage of test products in a written diary and reported if skin signs and symptoms occurred during the study period. The diaries were evaluated by investigators for compliance and adverse events after study completion. Subjects’ compliance was also monitored by measuring the amount of moisturizer remaining when the subjects returned provided moisture bottles at their last visit.

Measurements

Total Clinical Score (TCS)[12] of erythema, scale and fissures as well as VDS[13] were collected on every visit. On day 15, subjects in the treatment group refrained from applying moisturizer in the morning to ensure minimal contamination of skin spectra with moisturizer usage on the same day. TCS is the sum of three symptoms, i.e., erythema (0=no erythema, 1=slight erythema, 2=moderate uniform redness, 3=intense redness, 4=fiery red with edema), scaling (0=no scaling, 1=fine scaling, 2=moderate scaling, 3=severe scaling with large flakes), and fissure (0=no crack/fissure, 1=fine cracks, 2=single or multiple broader fissures, 3=wide cracks with hemorrhage or exudation). Thus, the TCS could range from 0 to 10. VDS was scored on a 5-point scale (0=none, 1=mild, 2=moderate, 3=severe, 4=very severe).

Subjective itch-related quality of life (ItchyQoL)[14] was obtained on screening day (7days before baseline, day 1) and day 15. The ItchyQoL is a measure of the frequency that the current skin condition impacts QoL as well as how bothersome the impact is to QoL across three main components: symptoms, daily function, and emotions. The ItchyQoL frequency questionnaire is a 22-item scale and the bothersome scale is 15 items. Numeric scores of 1–5 were assigned for each question in frequency scale (1=never; 2=rarely; 3=sometimes; 4=often; 5=all the time) and in bothersome scale (1=not bothered; 2=little bothered; 3=somewhat bothered; 4=very bothered; 5=severely bothered). Subscores for three constructs (symptoms, functioning, and emotions) and overall score, the sum of the three components, for both frequency scale and bothersome scale were recorded. A higher score corresponds to a more negative impact on QoL. In addition, subjects in the treatment group were provided Product In Use Questionnaires on day 15. Numeric scores of 1–5 were assigned for each question (1=strongly disagree; 2=disagree somewhat; 3=neutral; 4=agree somewhat; 5=strongly agree). Adverse events were monitored throughout the study.

Statistical Analysis

Within participant differences between baseline (day 1) and the end of the study (day 15) were calculated for most measures. The ItchyQoL questionnaire was collected at screening day and day 15, therefore, screening day served as the baseline measure. Most of the measures were discrete or not normally distributed so non-parametric methods were used. These data were summarized using medians and interquartile ranges (IQRs), within group changes were assessed using Wilcoxon signed-rank tests, and differences between the randomization groups were assessed using Wilcoxon rank-sum tests. Statistical analysis was performed using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC). All tests were two-sided and significance was set at p<0.05.

Results

Participants

A total of 54 participants with moderate to severe dry skin were randomized, and among those 52 participants completed the study (1 was determined to have been ineligible after completing visit 1, and 1 follow-up loss). We have restricted our reporting to these 52 participants (treatment group: 39 participants, control group: 13 participants). Subject demographics between groups were balanced at enrollment (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of participants

| Characteristics | Treatment (n=39) | Control (n=13) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age in yrs, median (IQR) | 30 (24–53) | 24 (23–35) | 0.18 |

| Sex male, n (%) | 14 (36%) | 3 (23%) | 0.51 |

| Race/Ethnicity, n (%) | |||

| White | 19 (49%) | 6 (46%) | |

| African American | 11 (28%) | 4 (31%) | 0.93 |

| Hispanic | 2 (5%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Asian | 6 (15%) | 2 (15%) | |

| Others | 1 (3%) | 1 (8%) |

Physician assessed clinical score

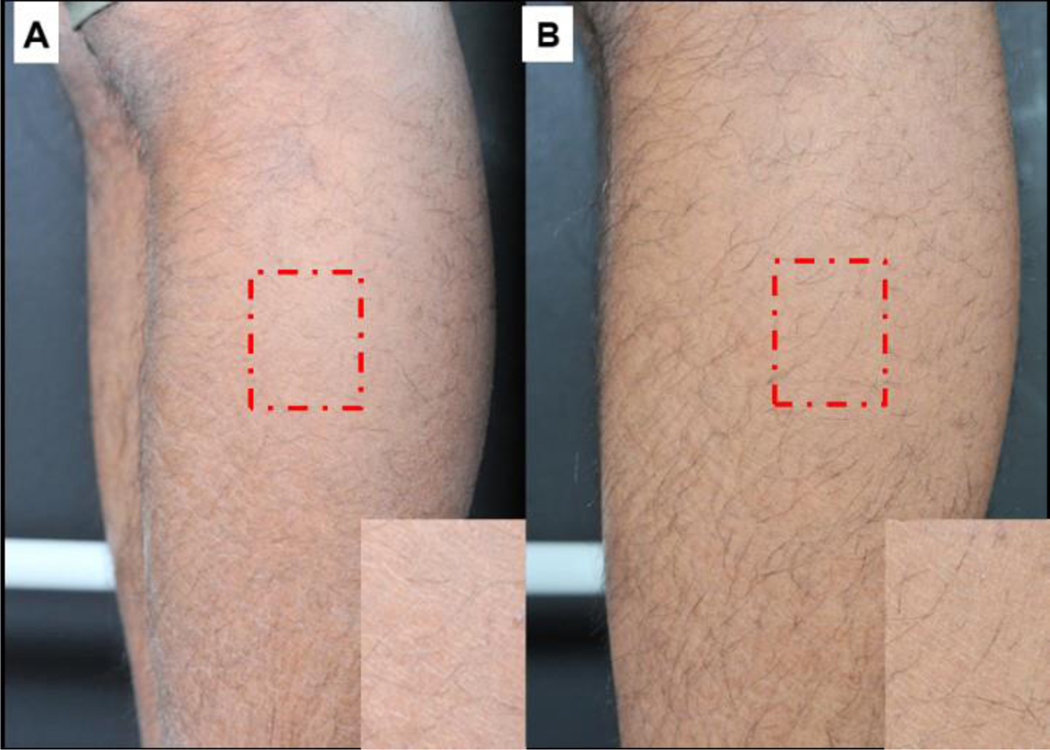

Dryness and erythema were improved clinically in the treatment group (Figure 1). TCS (sum of erythema, scale and fissures) and VDS by treatment arm at each time point are presented in Table 2. The within treatment group change and the differences between treatment group following 2 weeks of product application are included.

Figure 1.

Visual dryness improvement for treatment group on baseline/day 1 (A) and after 2 weeks of skin regimen usage on day 15 (B).

Table 2.

Total Clinical Score (TCS) and Visual Dryness Score (VDS) by treatment arm at baseline (day 1) and on the last study day (day 15)

| Site | Treatment group | Control group | Tx vs. Ctl p-valuea |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Day 1 | Day 15 | Δ(D15-D1)b | Day 1 | Day 15 | Δ(D15-D1)b | ||

| Total Clinical Score | |||||||

| Arms | 1(0.5–2.5) | 1(0–1) | −1(−1−0)* | 1(1–1.5) | 0.5(0–1) | −0.5(−1−0) | 0.17 |

| Legs | 3(2–4) | 1(1–2) | −1.5(−2.5- −1)* | 2(1.5–2) | 1(1–1) | −1(−1−0)* | 0.01† |

| Total | 8(4–12) | 4(2–6) | −4(−7- −2)* | 6(4–7) | 4(2–5) | −2 (−4- −1)* | 0.01† |

| Visual Dryness Score | |||||||

| Arms | 1(0–2) | 0(0–1) | −1(−2−0)* | 1(1–1) | 0(0–0.5) | −1(−1- −0.5)* | 0.25 |

| Legs | 2(2–3) | 0(0–1) | −2(−2- −1)* | 2(1.5–2) | 1(1–2) | −1(−1−0)* | 0.003† |

| Total | 6(4–10) | 2(0–2) | −4(−7- −2)* | 6(4–6) | 2(2–4) | −3(−4- −1)* | 0.02† |

Results presented are median (interquartile range) summary scores.

Wilcoxon rank-sum test comparing between treatment groups

Wilcoxon signed-rank test comparing within group, Tx treatment group, Ctl control group

p<0.05 intra-group analysis

p<0.05 inter-group analysis.

In within treatment group comparisons, the TCS and VDS for arms and legs of the treatment group were significantly improved on day 15 compared to baseline. Improvement in VDS was more prominent in the legs than arms. In comparing between treatment groups, the treatment group showed significantly more improvement in TCS and VDS compared to the control group after 2 weeks of product application for legs (TCS −1.5 vs −1, p=0.01; VDS −2 vs −1, p=0.003) and for total body score, the sum of the four sites (TCS −4 vs −2, p=0.01; VDS −4 vs −3, p=0.02), but not significantly different for arms.

When evaluating each subscale in the TCS (erythema, scale and fissures), the scale scores were significantly more improved in the treatment group than the control group whereas erythema and fissure scores were not significantly improved (data not shown).

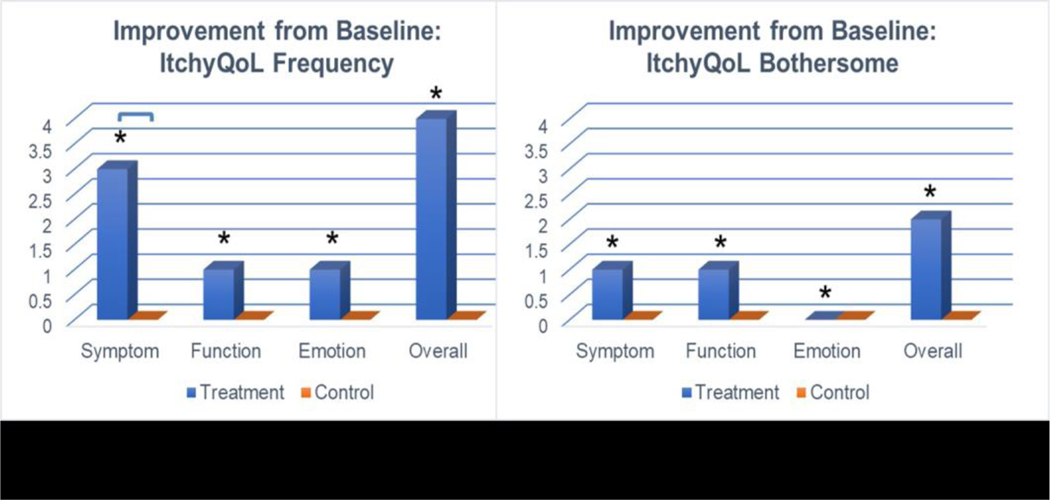

ItchyQoL survey questionnaires

Table 3 shows the of ItchyQoL scores of 22-items of frequency scale and 15-items of bothersome scale. At screening, the baseline scores of frequency scale and bothersome scale for three components (symptom, function, and emotion) were not significantly different between treatment and control groups (data not shown). The three components of the ItchyQoL showed significant improvement only in the treatment group (Figure 1). For the frequency scale, symptom scores showed significantly greater improvement in the treatment compared to the control group (−3 vs 0, p=0.01) and a marginal effect for emotion between groups (−1 vs 0, p=0.06) (Table 3). No components of the ItchyQoL scale changed from baseline in the control group for either frequency or bothersome scales.

Table 3.

ItchyQoL scores in 22-item of frequency scale and 15-item of bothersome scale by treatment arm on screening day and on the last study day (day 15)

| Measure | Treatment group | Control group | Tx vs. Ctl p- valuea |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Screening day | Day 15 | Δ(Day 15- screening day) b | Screening day | Day 15 | Δ(Day 15- screening day) b | ||

| Frequency | |||||||

| Symptom | 14 (11–17) | 11(8–13) | −3(−4- −1)* | 15(8–17) | 14(12–16) | 0(−2−2) | 0.01† |

| Function | 14(9–17) | 11(8–15) | −1(−3−0) * | 11(9–17) | 12.5(9.5–17) | 0(−2−2.5) | 0.21 |

| Emotion | 10(9–16) | 8(7–12) | −1(−4−0) * | 8 (7–12) | 9(8–12.5) | 0(−1.5−1.5) | 0.06 |

| Overall | 29(23–35) | 23(19–29) | −4(−6- −1) * | 26(19–32) | 28.5(21.5–33) | 0(−5.5−2) | 0.10 |

| Bothersome | |||||||

| Symptom | 12(8–17) | 9(7–12) | −1(−4−0) * | 12(6–16) | 11(10–14) | 0(−3−2) | 0.11 |

| Function | 11(8–15) | 9(7–14) | −1(−3−0) * | 11(8–15) | 10(9–13) | 0(−2−2) | 0.26 |

| Emotion | 3(2–4) | 2(2–4) | 0(−1−0) * | 2.5(2–5) | 2(2–3) | 0(−0.5−0.5) | 0.16 |

| Overall | 24(16–31) | 18(15–25) | −2(−6−0) * | 25(15–33) | 21(19–26) | 0(−4−2) | 0.21 |

Results presented are median (interquartile range) summary scores.

Wilcoxon rank-sum test comparing treatment groups

Wilcoxon signed-rank test comparing within group change, Tx treatment group, Ctl control group

p<0.05 intra-group analysis

p<0.05 inter-group analysis.

Frequency items are scored on scale of 1–5 (1 = never, 2 = rarely, 3 = sometimes, 4 = often, 5 = all the time) and bothersome items are scored on scale of 1–5 (1 = not bothered, 2 =little bothered, 3 = somewhat bothered, 4 = very bothered, 5 = severely bothered).

Product In Use Questionnaires

The majority of participants in the treatment group agreed that the regimen led to decreases in irritation, dryness, and pruritus and contributed to skin smoothness, softness and improvement in skin texture at day 15 (Table 4).

Table 4. Product In Use Questionnaires.

Percentage of subjects in treatment group with improvement following 2 weeks of moisturizer usage (agree or strongly agree response) (n=39).

| The moisturizer soothed irritated skin | 77% |

| The moisturizer relieved itchy skin | 69% |

| The moisturizer improved skin texture | 82% |

| Skin feels more moisturized | 87% |

| Skin feels softer | 82% |

| Skin is visibly improved | 74% |

| Skin not dry and itchy | 87% |

| Soothed irritated skin immediately | 51% |

| Feel happier in relationship | 50% |

| I can wear what I want | 64% |

Safety

No study related adverse events or serious adverse events were reported.

Discussion

This study evaluated the effect of regular usage of a skin care regimen consisting of a mild cleanser followed by a glycerin-rich moisturizing lotion in participants with moderate to severe dry skin. We observed improvement of dry skin after two weeks of product application in subjective and objective measurements. We found significantly greater improvement of clinical scores (TCS and VDS) in the treatment group than control group demonstrating that the moisturizer was effective in improving dry skin. Moreover, participants’ quality of life improved after the usage of skin care regimen. The majority of participants in the treatment group agreed that the regimen led to decreases in irritation, dryness, and pruritus and contributed to improved skin smoothness, softness, and skin texture.

In clinical scores of TCS and VDS, we observed greater improvement in treatment group than control group for legs, but not observed for arms. Legs are more often affected by xerosis and the level of dryness is more severe than arms, thus the improvement may be more pronounced in legs [15]. Moisturizer that is properly formulated is the mainstay of dry skin treatment [16]. Besides moisturizer, mild cleanser is important in alleviating dry skin given that harsh soaps containing detergents strip away natural emollients in the skin, causing further drying and irritation [17]. This likely explains the modest improvement that we observed in the control group who only used a gentle cleanser. Therefore, establishing a standardized skin care regimen is important and these benefits have been observed when compared to routine skin care on dry skin in nursing home residents [18]. Although little is known regarding the efficacy of different types of skin care products because head-to-head comparisons are lacking, it is generally accepted that using low irritating cleansers and humectants (occlusive-containing lipophilic emulsions) improve skin health[18, 19]. We used a moisturizer with a mix of wax and oils that deliver skin protection and physiologic lipids that are able to traverse the stratum corneum and mingle with epidermal lipids [9]. The glycerin, a humectant in the moisturizer, delivers moisture to the skin to promote lipid biosynthesis and NMF formation in dry skin leading to alleviation of xerosis.

Among three components of TCS, a significantly greater improvement in scaling subscore was found in the treatment compared to control group implying that the moisturizer has a positive effect in enhancing impaired desquamation properties in dry skin. Dry skin is associated with incomplete breakdown of desmosomes which are abnormally retained in the superficial layer of xerotic stratum corneum resulting in skin scaling and flaking [20]. The improvement in scaling in this study can be explained by the enhanced activity of the enzyme involved in the desquamation process due to an increased skin hydration level by the moisturizer [20, 21]. Previous studies have shown that applying moisturizers upregulates gene expression of epidermal enzymes that are involved in lipid processing, keratinocyte differentiation, and desquamation leading to repair of the skin barrier function [22–25].

Furthermore participants’ quality of life improved overall and in all three domains, symptom, daily function, and emotion, after the application of skin regimen in the treatment group whereas no significant change was reported in the control group in both frequency and bothersome scales. In intergroup analysis, scores in symptom domain showed significantly greater improvement in treatment compared to control group in frequency scales indicating that the moisturizer mainly alleviates dry skin symptoms to enhance one’s quality of life. The improvement in symptom score was not significant in bothersome scale implying that frequency scale is a more sensitive tool to detect change in scores. Since it was first devised by Desai et al.[26], ItchyQoL has been validated and applied in various pruritic skin diseases including atopic dermatitis, psoriasis, and senile xerosis and welcomed as a useful tool for the investigation of QoL in chronic pruritus patients[27–30].

In addition, we saw high participant satisfaction scores with no adverse events. Approximately 80% of participants in active treatment group agreed that the moisturizer relieved skin dryness, pruritus, and irritation, and led their skin to be more moisturized, softer with improved texture. Our data support that a regular skin care regimen incorporating once daily mild cleanser and twice a day glycerin-rich moisturizing lotion for two weeks can greatly improve skin health as well as patient’s well-being.

This study has several limitations. It was an exploratory study therefore determination of effective sample size was not conducted. The small number of participants and the relatively short intervention period is another limitation. However, we observed significant improvement in skin dryness and quality of life relative to the control population in this limited time of product usage suggesting that short intervention of a proper skin care regimen can lead to positive effects. Participants were randomized 3:1 ratio instead of 1:1 allocation in order to assess the skin care regimen in more participants thus enhancing recruitment and minimizing drop-out rates. Biophysical measurements such as skin hydration or trans-epidermal water loss were not included in this study. The amount of product use was not strictly standardized although we measured the leftover moisturizer in the package at the end of study. We used complete-case-analysis rather than intention-to-treat analysis for clinical trials which may lead to bias to some extent [31].

In conclusion, this study adds evidence collected from multiple validated scales that the regular use of a skin care regimen consisting of mild cleanser and a glycerin-rich moisturizer can improve dry skin and skin health as well as enhance patients’ quality of life. The effects of a consistent skin care regimen on dry skin may have greater impact on patient’s skin health due to the high prevalence of dry skin. Physicians should be aware of the importance and benefits of a consistent skin care regimen for sensitive skin and incorporate this regimen as part of their management plan, especially in patients with dry skin.

Figure 2.

ItchyQoL summary of improvement in 22-item of frequency scale and 15-item of bothersome scale. Results presented are median summary scores. *indicates significance in intra-group analysis, connected lines indicate significance in inter-group analysis, at p<0.05.

Acknowledgments

Funding sources:

K. A. Carson’s work on the project was funded in part by the Johns Hopkins Institute for Clinical and Translational Research, under grant number UL1 TR001079 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, a component of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and the NIH Roadmap for Medical Research.

Disclosure statement

This study was funded by Unilever Beauty and Personal Care, U.S. Study design and data analysis was performed independently by Johns Hopkins.

Footnotes

IRB review stats: This study was reviewed and approved by the Johns Hopkins Medicine Institutional Review Board as IRB00165140.

This study was registered in clinicaltrials.gov as NCT03497130.

Conflicts of Interest: Sewon Kang, MD has served on the Advisory Council of Unilever, and has received honorarium.

References

- 1.White-Chu EF, Reddy M (2011) Dry skin in the elderly: complexities of a common problem. Clinics in dermatology 29:37–42. 10.1016/j.clindermatol.2010.07.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Moncrieff G, Cork M, Lawton S, et al. (2013) Use of emollients in dry-skin conditions: consensus statement. Clinical and Experimental Dermatology 38:231–238. 10.1111/ced.12104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Guenther L, Lynde CW, Andriessen A, et al. (2012) Pathway to dry skin prevention and treatment. Journal of cutaneous medicine and surgery 16:23–31. 10.1177/120347541201600106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baron SE, Cohen SN, Archer CB, British Association of Dermatologists and Royal College of General Practitioners (2012) Guidance on the diagnosis and clinical management of atopic eczema. Clinical and Experimental Dermatology 37:7–12. 10.1111/j.1365-2230.2012.04336.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rawlings A V, Matts PJ (2005) Stratum corneum moisturization at the molecular level: an update in relation to the dry skin cycle. The Journal of investigative dermatology 124:1099–110. 10.1111/j.1523-1747.2005.23726.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lodén M, Lodén M (2003) Do moisturizers work? Journal of cosmetic dermatology 2:141–9. 10.1111/j.1473-2130.2004.00062.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lodén M (2003) Role of topical emollients and moisturizers in the treatment of dry skin barrier disorders. American journal of clinical dermatology 4:771–88. 10.2165/00128071-200304110-00005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Simpson E, Böhling A, Bielfeldt S, et al. (2013) Improvement of skin barrier function in atopic dermatitis patients with a new moisturizer containing a ceramide precursor. The Journal of dermatological treatment 24:122–5. 10.3109/09546634.2012.713461 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chamlin SL, Kao J, Frieden IJ, et al. (2002) Ceramide-dominant barrier repair lipids alleviate childhood atopic dermatitis: changes in barrier function provide a sensitive indicator of disease activity. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology 47:198–208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hoffman L, Subramanyan K, Johnson AW, Tharp MD (2008) Benefits of an emollient body wash for patients with chronic winter dry skin. Dermatologic therapy 21:416–21. 10.1111/j.1529-8019.2008.00225.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ishikawa J, Yoshida H, Ito S, et al. (2013) Dry skin in the winter is related to the ceramide profile in the stratum corneum and can be improved by treatment with a Eucalyptus extract. Journal of cosmetic dermatology 12:3–11. 10.1111/jocd.12019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ortonne J-P, Queille-Roussel C (2007) Evaluation of the effect of Dardia Lipo Line on skin inflammation induced by surfactants using the repeated open-application test. Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology : JEADV 21 Suppl 2:19–25. 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2007.02383.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chang ALS, Chen SC, Osterberg L, et al. (2018) A daily skincare regimen with a unique ceramide and filaggrin formulation rapidly improves chronic xerosis, pruritus, and quality of life in older adults. Geriatric nursing (New York, NY) 39:24–28. 10.1016/j.gerinurse.2017.05.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Desai NS, Poindexter GB, Monthrope YM, et al. (2008) A pilot quality-of-life instrument for pruritus. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology 59:234–44. 10.1016/j.jaad.2008.04.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lechner A, Lahmann N, Lichterfeld-Kottner A, et al. (2019) Dry skin and the use of leave-on products in nursing care: A prevalence study in nursing homes and hospitals. Nursing Open 6:189–196. 10.1002/nop2.204 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Buraczewska I, Berne B, Lindberg M, et al. (2007) Changes in skin barrier function following long-term treatment with moisturizers, a randomized controlled trial. British Journal of Dermatology 156:492–498. 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2006.07685.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bornkessel A, Flach M, Arens-Corell M, et al. (2005) Functional assessment of a washing emulsion for sensitive skin: mild impairment of stratum corneum hydration, pH, barrier function, lipid content, integrity and cohesion in a controlled washing test. Skin research and technology : official journal of International Society for Bioengineering and the Skin (ISBS) [and] International Society for Digital Imaging of Skin (ISDIS) [and] International Society for Skin Imaging (ISSI) 11:53–60. 10.1111/j.1600-0846.2005.00091.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hahnel E, Blume-Peytavi U, Trojahn C, et al. (2017) The effectiveness of standardized skin care regimens on skin dryness in nursing home residents: A randomized controlled parallel-group pragmatic trial. International Journal of Nursing Studies 70:1–10. 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2017.02.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kottner J, Lichterfeld A, Blume-Peytavi U (2013) Maintaining skin integrity in the aged: a systematic review. British Journal of Dermatology 169:528–542. 10.1111/bjd.12469 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rawlings A, Harding C, Watkinson A, et al. (1995) The effect of glycerol and humidity on desmosome degradation in stratum corneum. Archives of dermatological research 287:457–64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Watkinson A, Harding C, Moore A, Coan P (2001) Water modulation of stratum corneum chymotryptic enzyme activity and desquamation. Archives of dermatological research 293:470–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Buraczewska I, Berne B, Lindberg M, et al. (2009) Moisturizers change the mRNA expression of enzymes synthesizing skin barrier lipids. Archives of Dermatological Research 301:587–594. 10.1007/s00403-009-0958-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Candi E, Schmidt R, Melino G (2005) The cornified envelope: a model of cell death in the skin. Nature reviews Molecular cell biology 6:328–40. 10.1038/nrm1619 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rawlings A V, Harding CR (2004) Moisturization and skin barrier function. Dermatologic therapy 17 Suppl 1:43–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pons-Guiraud A (2007) Dry skin in dermatology: a complex physiopathology. Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology : JEADV 21 Suppl 2:1–4. 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2007.02379.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Desai NS, Poindexter GB, Monthrope YM, et al. (2008) A pilot quality-of-life instrument for pruritus. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology 59:234–44. 10.1016/j.jaad.2008.04.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zeidler C, Steinke S, Riepe C, et al. (2019) Cross-European validation of the ItchyQoL in pruritic dermatoses. Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology 33:391–397. 10.1111/jdv.15225 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Plewig N, Ofenloch R, Mettang T, Weisshaar E (2019) The course of chronic itch in hemodialysis patients: results of a 4‐ year follow‐up study of GEHIS (German Epidemiological Hemodialysis Itch Study). Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology 33:1429–1435. 10.1111/jdv.15483 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jang YH, Kim SM, Eun DH, et al. (2019) Validity and reliability of itch assessment scales for chronic pruritus in adults: A prospective multicenter study. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 10.1016/j.jaad.2019.06.043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ständer S, Steinke S, Augustin M, et al. (2019) Quality of Life in Psoriasis Vulgaris: Use of the ItchyQoL Question-naire in a Secukinumab Phase III Trial in Patients with Psoriasis Vulgaris. Acta Dermato Venereologica 99:0. 10.2340/00015555-3275 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ranganathan P, Pramesh CS, Aggarwal R (2016) Common pitfalls in statistical analysis: Intention-to-treat versus per-protocol analysis. Perspectives in clinical research 7:144–6. 10.4103/2229-3485.184823 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]