Abstract

Major depressive disorder (MDD) in late life is linked to increased risk of subsequent dementia, but it is still unclear exactly what pathophysiological mechanisms underpin this link. A potential mechanism related to elevated risk of dementia in MDD is increased levels of α-synuclein (α-Syn), a protein found in presynaptic neuronal terminals. In this study, we examined cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) levels of α-Syn in conjunction with biomarkers of neurodegeneration (amyloid-β 42, total and phospho tau) and synaptic dysfunction (neurogranin), and measures of memory ability, in 27 cognitively intact older individuals with MDD and 19 controls. Our results show that CSF α-Syn levels did not significantly differ across depressed and control participants, but α-Syn was directly associated with neurogranin levels, and indirectly linked to poorer memory ability. All in all, we found that α-Syn may be implicated in the association between late life MDD and synaptic dysfunction, although further research is needed to confirm these results.

Keywords: α-synuclein, late-life major depressive disorder, neurogranin, memory

Introduction

Links between depressive symptoms in late life and dementing illnesses, including Alzheimer’s disease (AD), have been reported in several studies (1–4). Individuals with depression have been reported to carry more than double the risk of converting to AD, diagnosed on clinical grounds, than controls (5), while individuals with mild cognitive impairment and dementia are more than twice as likely as controls to be depressed (6). However, understanding the exact nature of this relationship has proven a challenging task. Not all individuals with late-life depressive symptoms will develop dementia and for those who do, it is not always clear whether the depressive symptoms are a consequence of dementia, or contributing to its emergence.

In the past, we have proposed that a possible mediator of the link between late-life MDD and AD is the role played in the central nervous system by amyloid beta (Aβ). Pomara and Doraiswamy (7; see also 8) were first to suggest that chronic depression may lead to elevation of circulating Aβ levels independently of AD, specifically via increased platelet activation. In turn, due to the bidirectional receptor-mediated active transport of Aβ across the blood-brain barrier, increased circulating Aβ levels may result in higher brain concentration of the peptide. Consistent with this claim, we reported (4) that cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) levels of Aβ42, which are thought to inversely reflect brain amyloid deposits, were lower in older (at least 60 years of age), cognitively healthy individuals with MDD compared with controls. However, a later follow up study from our group (8) showed that, although reduced CSF Aβ42 levels remained sensitive to depressive symptoms, they tended to fluctuate longitudinally over a three-year span, and were not associated to cognitive health in subjects with late-life MDD.

An alternative, or complementary, potential mechanism for increased risk of dementia in individuals with late life MDD is related to increased levels of α-synuclein (α-Syn). α-Syn is a presynaptic protein that is highly expressed in cortical and sub-cortical areas (9). The protein may aggregate into Lewy bodies, a pathological protein misfolding process that potentially may start in the gut and spread to the CNS (10). α-Syn aggregation in the brain is a core feature of Parkinson’s disease and dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB) (11), but it may be implicated also in the pathophysiology of depression, leading to alterations in dopaminergic and serotoninergic neurotransmission (12). A recent report looking at serum levels of α-Syn (13) showed that individuals with MDD had higher levels than controls, regardless of age. In turn, α-Syn has been found to associate with synaptic dysfunction, as determined by CSF neurogranin (Ng) concentration, in Parkinson’s disease (11), suggesting that α-Syn may also reflect or promote synaptic dysfunction leading to cognitive impairment. Finally, depression has been reported to be a risk factor for Parkinson’s disease (14).

Considering the evidence above, it may be possible that while Aβ may influence the severity of depression in late life (4,8), and perhaps earlier, other mechanisms, namely mechanisms related to aggregation of α-Syn, are at play in affecting synaptic dysfunction and thereby cognitive decline. To test this hypothesis, we analysed CSF biomarkers in cognitively intact individuals with late life MD and controls, and measured memory performance. We carried out cross-sectional analyses and correlations within each clinical group. The CSF biomarkers included in the analyses were α-Syn, the A/T/N biomarkers (15), Aβ42, total tau (T-tau) and phosphorylated tau (P-tau), and Ng. Memory performance was measured by Buschke Selective Reminding Test (BSRT) total recall and the recency ratio (16, 17). Our hypothesis was that higher levels of CFS α-Syn would be associated with increased CSF Ng (indexing more synaptic dysfunction) and poorer memory ability.

Methods

Participants.

A total of 133 participants were recruited initially, of whom 47 individuals allowed lumbar puncture for collection of CSF, presented no MRI evidence of confluent deep or periventricular white matter hyperintensities, and had a Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE; 18) score of 28 or above were included in this study. Twenty-eight participants had a diagnosis of MDD, confirmed by a board-certified psychiatrist based on clinical evaluation and the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders (SCID), and 19 were healthy controls. No had history or symptoms of cognitive impairment. Demographic characteristics are summarised in Table 1 (see also 4). Participants received up to $450.00 in compensation for their time.

Table 1.

Demographic and Memory Characteristics of Study Participants by MDD diagnosis; The data are the mean ± standard deviation.

| Characteristic | Comparison Group | MDD Group | |

|---|---|---|---|

| (N=19) | (N=28) | p values (t tests) | |

| Age (years) | 68.1 ± 7.3 | 66.5 ± 5.4 | 0.41 |

| Education (years)a | 16.7 ± 2.7 | 16.5 ± 2.7 | 0.79 |

| 21-item HAM-D | 1.3 ± 1.6 | 13.7 ± 8.8 | <0.001 |

| MMSE | 29.5 ± 0.5 | 29.8 ± 0.6 | 0.13 |

| p values (χ2) | |||

| Females (n) | 12 (63%) | 10 (36%) | 0.12 |

21-item HAM-D: 21-item Hamilton Depression Rating Scale, MMSE: Mini-Mental State Examination.

= One missing data point.

Biomarkers.

Aβ levels were measured with electrochemiluminescence technology using the MS6000 Human Ab Ultra-Sensitive Kit (Meso Scale Discovery, Gaithersburg, Md.). T-tau levels were determined using a sandwich enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) (INNOTEST hTAU-Ag, Innogenetics, Ghent, Belgium), whereas P-tau was measured with a sandwich ELISA method (INNOTEST Phospho-Tau [181P], Innogenetics). CSF Ng concentration was measured using an inhouse sandwich ELISA [20]. All values lower than the detection threshold of 40 pg/mL were scored as 39 pg/mL. CSF α-Syn levels were determined with a ELISA method (Tecan Sunrise, Salzburg, Austria), following the procedure described by van Geel et al. [21].

Procedure.

The study procedure has been detailed previously [4]. Briefly, the study consisted of four visits on successive weeks. On visit 1, all participants provided consent and were assessed for: medical history, vital signs, and general cognitive ability (MMSE). Severity of depression was measured at this stage with the Hamilton Depression Scale (HAM-D, 21 items). On visit 2, participants received an MRI scan of the head, and a physical examination, including routine laboratory tests. On visit 3, participants underwent a comprehensive neuropsychological assessment that included memory evaluation with the BSRT [22, 23]. The BSRT (standard administration) involves the oral presentation of 16 unrelated nouns, which participants are asked to recall over several trials. In the first trial, participants are asked to free recall as many words as possible immediately after presentation of the study list; after this, participants are reminded of the items that were not retrieved and asked to recall all items again, over six subsequent trials; in a final delayed trial, participants are then asked to free recall the original study list, following a period of approximately 20 minutes from initial learning. Finally, a lumbar puncture was performed on a fourth visit, between 9am and 10am, after overnight fasting. This study was ethically approval by the institutional review boards of the Nathan Kline Institute for Psychiatric Research, and the New York University School of Medicine.

Design and Analysis.

First we examined whether there were differences across late life MDD and control groups in Ng and α-Syn levels (note that differences in Aβ42 were already reported in 4), and memory scores. Due to the non-normal nature of these data, we performed non-parametric analyses. Second, we carried out a series of Spearman correlations separately in individuals with late-life MDD and controls. The variables included in the analyses were: CSF α-Syn, Ng, Aβ42, T-and P-tau, BSRT total recall and the recency ratio. Total recall was calculated by adding the number of all recalled items over the seven learning trials of the BSRT; and the recency ratio is provided by the ratio between recall of the last four presented items in the first learning trial and in the delayed trial, using the adjustment provided here [17]. Of note, whereas lower total and delayed recall are indicative of more memory loss, the opposite is true of the recency ratio. To avoid repeating previous findings, and to take into account and limit the high volume of tests, we focused only on correlations involving either Ng, α-Syn or both. We report unadjusted p values and, when reaching conventional significance (p ≤ 0.05), we qualify the finding with adjusted (with False Discovery Rate; 24), p values. As a separate analysis, we also carried out correlations between CSF α-Syn and HAM-D in depressed and controls, separately.

Results

Table 1 reports cross-sectional comparisons of demographic characteristics. Depression severity was higher in the MDD group, and thus the original diagnosis was consistent with the depressive state of the sample. None of the other demographic characteristics differed across groups.

Comparisons across groups.

Except for Aβ42 [see 4], none of the variables of interest differed significantly between depressed individuals and controls (p values ≥ 0.200, Z scores ≤ 1.3). Means and standard deviations are reported in Table 2, except for biomarker data reported elsewhere [see 4].

Table 2.

Comparisons of variables of interest by MDD diagnosis; The data are the mean ± standard deviation.

| Characteristic | Comparison Group | MDD Group | |

|---|---|---|---|

| (N=19) | (N=28) | p values (Mann Whitney) | |

| α-Syn (ng/mL) | 14.1 ± 16.1 | 16.9 ± 16.2 | 0.205 |

| Ng (pg/mL)a | 100.8 ± 91.4 | 100.3 ± 124.3 | 0.351 |

| Total recall (number of words) | 64.4 ± 12.3 | 64.9 ± 13.9 | 0.410 |

| Recency ratio | 1.9 ± 2.3 | 1.7 ± 1.9 | 0.673 |

= One missing data point.

Correlations late-life MDD.

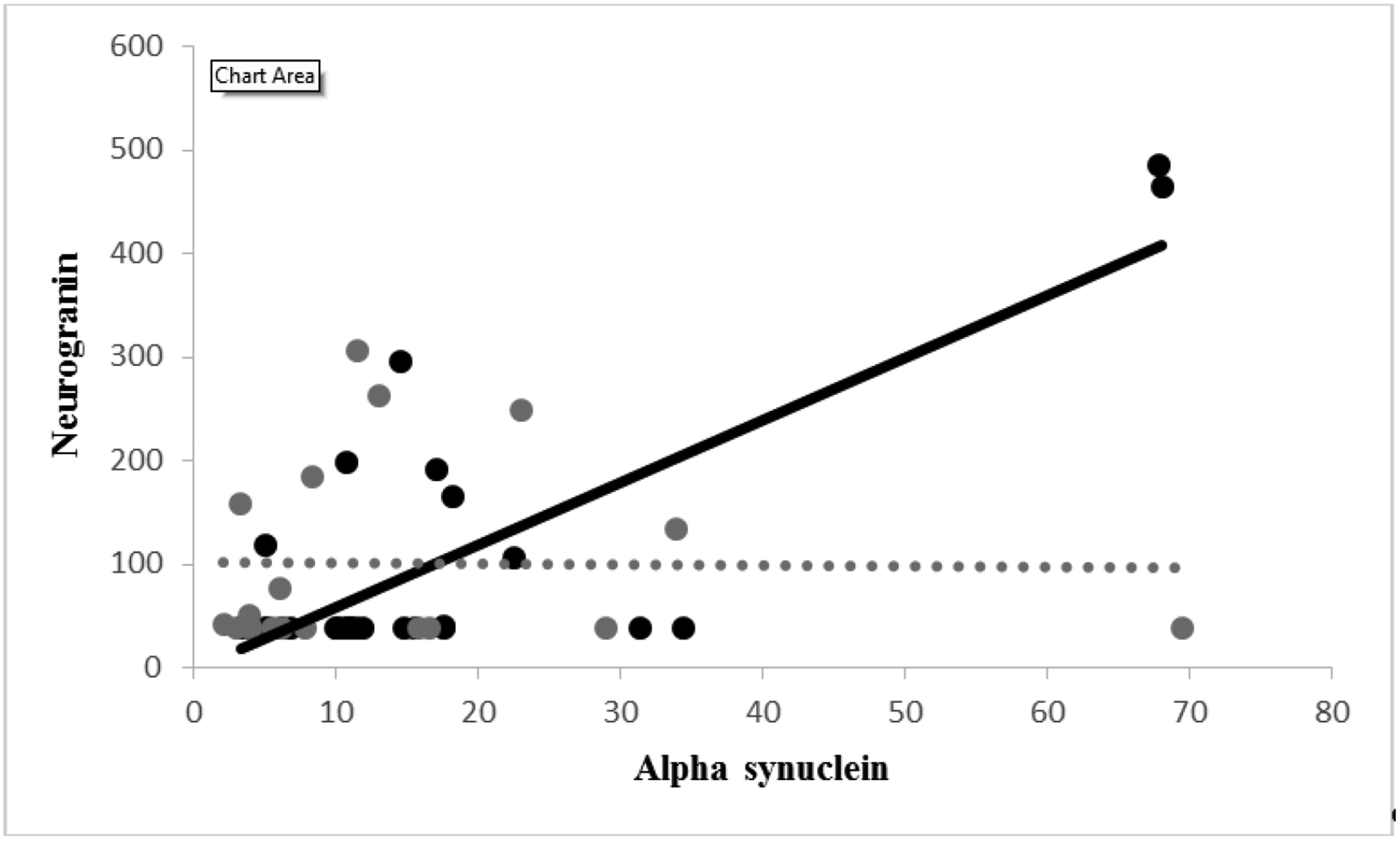

α-Syn correlated positively with Ng (rho = 0.444, p = 0.018; see Figure), but not when adjusting the p value for multiple tests (0.198). α-Syn did not correlate with Aβ42 levels (rho = 0.199, p = 0.310), T- and P-tau levels (p values ≥ 0.500), or memory (p values ≥ 0.200). Ng displayed a correlation with P-tau (rho = 0.374, p = 0.050), which was not significant according to adjustment (adjusted p = 0.348). Ng was also positively correlated with the recency ratio (rho = 0.593 p = 0.001), surviving the adjustment (adjusted p value = 0.022). Ng was not otherwise correlated with the other variables (p values ≥ 0.069). See Figure.

Figure 1.

Relationship between α-synuclein (X-axis; ng/mL) and neurogranin (Y-axis; pg/mL).

Correlations controls.

None of the correlations in this set approached significance (p values ≥ 0.145; see Figure).

Correlations with severity of depression.

α-Syn did not correlate with the HAM-D score in either group (p values ≥ 0.350).

Discussion

To our knowledge, this was the first report examining CSF α-Syn in individuals with late life MDD. We hypothesised that higher levels of CFS α-Syn would be associated with increased CSF Ng, which signals greater synaptic dysfunction, and poorer memory ability. The results of our study only confirmed our hypothesis in part. First, we did find that elevated levels of CSF α-Syn in depressed individuals were associated with increased CSF Ng, but this finding did not survive statistical checks for multiple testing. This suggests that this relationship should be considered exploratory, at this time, and requires further confirmation. Second, we did not observe a direct association between CSF α-Syn and memory ability in the depressed subjects, but we did see an indirect association with memory ability, as indexed by the recency ratio, such that memory was poorer when CSF levels of Ng were higher.

We did not observe any association between CSF α-Syn and the ATN biomarkers in either cohort. This finding is not entirely consistent with that in a recent report by Vergallo et al. [25], who found that CSF α-Syn was positively correlated with CSF T- and P-tau levels as well as brain amyloid β levels. A few notable differences across the two studies are the following. First, our subjects were diagnosed with MDD, whereas Vergallo et al.’s participants are free of clinical psychiatric diagnoses. Taking that into consideration, our results are consistent with Vergallo et al.’s [25] since we did not find any association between CSF α-Syn and ATN biomarkers in controls either. However, it should be noted that Vergallo et al.’s subjects reported subjective memory complaints, which often are linked with mood disturbances [26]. Second, our participants were generally younger, and age may have an impact on the relationship between CSF α-Syn and other biomarkers.

Elevations of CSF Ng, a post-synaptic protein, have been reported to reflect synaptic degeneration in both AD and mild cognitive impairment (MCI), a preclinical stage of AD, and are associated with greater cognitive deficits and longitudinal decline [20, 27]. A lack of significant associations between CSF α-Syn and neurodegenerative markers in depression, in conjunction with a positive correlation between CSF α-Syn and CSF Ng concentrations, may suggest that changes in presynaptic aggregations of α-Syn impact on neuronal activity and Ng release as reported for PD [11].

We did not observe a difference in CSF α-Syn levels across individuals with late-life MDD and controls. This finding is in contrast with what previously reported by Ishiguro et al. [13], who examined serum α-Syn levels. It is possible, therefore, that, while depression-related differences are detectable in serum, they are harder to identify when examining CSF. However, a more likely explanation, is that our sample was smaller compared to that of Ishiguro et al. (47 total subjects vs. 235) and, hence, we may have failed to detect a difference in α-Syn levels across groups due to lack of power. Moreover, their depressed participants were on average more depressed (mean HAM-D score of 24) than ours (mean HAM-D score of 15). More research is needed to confirm our findings.

A final point to note is that the recency ratio was sensitive to CSF Ng levels in depression, but not BSRT total recall. As we have suggested in recent papers [17], the recency ratio, which can be extracted from most neuropsychological tests of memory, compares favourably to most conventional scores employed to estimate memory ability in older individuals.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by an NIMH grant to NP (R01 MH 080405), Swedish Research Council grants to HZ (2018-02532) and KB (2012-2288), the Swedish Brain Foundation, the Swedish Alzheimer Foundation, and Torsten Söderberg Foundation at the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences. HZ is a Wallenberg Academy Fellow. Parts of this study were presented by the lead author at the Alzheimer’s Association International Conference in London, July 2017.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest

HZ and KB are co-founders of Brain Biomarker Solutions in Gothenburg AB, a GU Ventures-based platform company at the University of Gothenburg. KB has served as a consultant or at advisory boards for Alzheon, Axon Neuroscience, BioArctic, Biogen, Eli Lilly, Fujirebio Europe, IBL International, Pfizer, and Roche Diagnostics. HZ has served at scientific advisory boards for Samumed, Wave, CogRx and Roche Diagnostics, and has given lectures in symposia sponsored by Alzecure and Biogen.

No other conflicts of interests are disclosed.

References

- 1.Almeida OP, Hankey GJ, Yeap BB, Golledge J, Flicker L. Depression as a modifiable factor to decrease the risk of dementia. Translational psychiatry. 2017. May;7(5):e1117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Green RC, Cupples LA, Kurz A, Auerbach S, Go R, Sadovnick D, Duara R, Kukull WA, Chui H, Edeki T, Griffith PA. Depression as a risk factor for Alzheimer disease: the MIRAGE Study. Archives of neurology. 2003. May 1;60(5):753–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kokmen E, Beard CM, Chandra V, Offord KP, Schoenberg BS, Ballard DJ. Clinical risk factors for Alzheimer’s disease A population‐ based case‐ control study. Neurology. 1991. September 1;41(9):1393-. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pomara N, Bruno D, Sarreal AS, Hernando RT, Nierenberg J, Petkova E, Sidtis JJ, Wisniewski TM, Mehta PD, Pratico D, Zetterberg H. Lower CSF amyloid beta peptides and higher F2-isoprostanes in cognitively intact elderly individuals with major depressive disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2012. May;169(5):523–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jorm AF. History of depression as a risk factor for dementia: an updated review. Australian & New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry. 2001. December;35(6):776–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Snowden MB, Atkins DC, Steinman LE, Bell JF, Bryant LL, Copeland C, Fitzpatrick AL. Longitudinal association of dementia and depression. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2015. September 30;23(9):897–905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pomara N, Doraiswamy PM. Does increased platelet release of Aβ peptide contribute to brain abnormalities in individuals with depression?. Medical hypotheses. 2003. May 31;60(5):640–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pomara N, Bruno D. Major Depression May Lead to Elevations in Potentially Neurotoxic Amyloid Beta Species Independently of Alzheimer Disease. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2016. September 1;24(9):773–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Emamzadeh FN. Alpha-synuclein structure, functions, and interactions. Journal of research in medical sciences: the official journal of Isfahan University of Medical Sciences. 2016;21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dinan TG, Cryan JF. Gut feelings on Parkinson’s and depression. InCerebrum: the Dana forum on brain science 2017. March (Vol. 2017). Dana Foundation. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Selnes P, Stav AL, Johansen KK, Bjørnerud A, Coello C, Auning E, Kalheim L, Almdahl IS, Hessen E, Zetterberg H, Blennow K. Impaired synaptic function is linked to cognition in Parkinson’s disease. Annals of clinical and translational neurology. 2017. October;4(10):700–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Frieling H, Gozner A, Römer KD, Wilhelm J, Hillemacher T, Kornhuber J, De Zwaan M, Jacoby GE, Bleich S. Alpha-synuclein mRNA levels correspond to beck depression inventory scores in females with eating disorders. Neuropsychobiology. 2008;58(1):48–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ishiguro M, Baba H, Maeshima H, Shimano T, Inoue M, Ichikawa T, Yasuda S, Shukuzawa H, Suzuki T, Arai H. Increased serum levels of α-synuclein in patients with major depressive disorder. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2019. March 1;27(3):280–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Piccinni A, Marazziti D, Veltri A, Ceravolo R, Ramacciotti C, Carlini M, Del Debbio A, Schiavi E, Bonuccelli U, Dell’Osso L. Depressive symptoms in Parkinson’s disease. Comprehensive psychiatry. 2012. August 1;53(6):727–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang S, Mao S, Xiang D, Fang C. Association between depression and the subsequent risk of Parkinson’s disease: A meta-analysis. Progress in Neuro-Psychopharmacology and Biological Psychiatry. 2018. August 30;86:186–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jack CR Jr, Bennett DA, Blennow K, Carrillo MC, Dunn B, Haeberlein SB, Holtzman DM, Jagust W, Jessen F, Karlawish J, Liu E. NIA-AA Research Framework: Toward a biological definition of Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s & Dementia. 2018. April 1;14(4):535–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bruno D, Koscik RL, Woodard JL, Pomara N, Johnson SC. The recency ratio as predictor of early MCI. International psychogeriatrics. 2018. December;30(12):1883–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bruno D, Reichert C, Pomara N. The recency ratio as an index of cognitive performance and decline in elderly individuals. Journal of clinical and experimental neuropsychology. 2016. October 20;38(9):967–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. “Mini-mental state”: a practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. Journal of psychiatric research. 1975. November 30;12(3):189–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Portelius E, Zetterberg H, Skillbäck T, Törnqvist U, Andreasson U, Trojanowski JQ, Weiner MW, Shaw LM, Mattsson N, Blennow K. Cerebrospinal fluid neurogranin: relation to cognition and neurodegeneration in Alzheimer’s disease. Brain. 2015. September 15;138(11):3373–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.van Geel WJ, Abdo WF, Melis R, Williams S, Bloem BR, Verbeek MM. A more efficient enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for measurement of α-synuclein in cerebrospinal fluid. Journal of neuroscience methods. 2008. February 15;168(1):182–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bruno D, Grothe MJ, Nierenberg J, Zetterberg H, Blennow K, Teipel SJ, Pomara N. A study on the specificity of the association between hippocampal volume and delayed primacy performance in cognitively intact elderly individuals. Neuropsychologia. 2015. March 31;69:1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Buschke H, Fuld PA. Evaluating storage, retention, and retrieval in disordered memory and learning. Neurology. 1974. November 1;24(11):1019-. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y. Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. Journal of the Royal statistical society: series B (Methodological). 1995. January;57(1):289–300. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vergallo A, Bun RS, Toschi N, Baldacci F, Zetterberg H, Blennow K, Cavedo E, Lamari F, Habert MO, Dubois B, Floris R. Association of cerebrospinal fluid α-synuclein with total and phospho-tau181 protein concentrations and brain amyloid load in cognitively normal subjective memory complainers stratified by Alzheimer’s disease biomarkers. Alzheimer’s & Dementia. 2018. December 1;14(12):1623–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yates JA, Clare L, Woods RT, MRC CFAS. Subjective memory complaints, mood and MCI: a follow-up study. Aging & mental health. 2017. March 4;21(3):313–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kvartsberg H, Duits FH, Ingelsson M, Andreasen N, Öhrfelt A, Andersson K, Brinkmalm G, Lannfelt L, Minthon L, Hansson O, Andreasson U. Cerebrospinal fluid levels of the synaptic protein neurogranin correlates with cognitive decline in prodromal Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s & Dementia. 2015. October 1;11(10):1180–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]