Abstract

Background:

How clinical teams function varies across sites and may affect follow-up of abnormal fecal immunochemical test (FIT) results.

Aims:

This study aimed to identify the characteristics of clinical practices associated with higher diagnostic colonoscopy completion after an abnormal FIT result in a multi-site integrated safety-net system.

Methods:

We distributed survey questionnaires about tracking and follow-up of abnormal FIT results to primary care team members across 11 safety-net clinics from January 2017 to April 2017. Surveys were distributed at all-staff clinic meetings and electronic surveys sent to those not in attendance. Participants received up to three reminders to complete the survey.

Results:

Of the 501 primary care team members identified, 343 (68.5%) completed the survey. In the four highest performing clinics, nurse managers identified at least two team members who were responsible for communicating abnormal FIT results to patients. Additionally, team members used a clinic-based registry to track patients with abnormal FIT results until colonoscopy completion. Compared to higher-performing clinics, lower-performing clinics more frequently cited competing health issues (56% vs. 40%, p=0.03) and lack of patient priority (59% vs. 37%, p<0.01) as barriers and were also more likely to discuss abnormal results at a clinic visit (83% vs. 61%, p<0.01).

Conclusions:

Our findings suggest organized and dedicated efforts to communicate abnormal FIT results and track patients until colonoscopy completion through registries is associated with improved follow-up. Increased utilization of electronic health record platforms to coordinate communication and navigation may improve diagnostic colonoscopy rates in patients with abnormal FIT results.

Keywords: Colorectal Cancer, Fecal Immunochemical Test, Electronic Health Records, Diagnostic Colonoscopy, Standardized Workflows

Introduction

There is clear evidence that screening by stool-based tests is cost-effective[1] and saves lives[2]; however, screening remains underutilized, especially in racial/ethnic minorities and low-income populations.[3] In safety-net health care settings,[4] where many medically underserved populations receive care, the fecal immunochemical test (FIT) is a cornerstone of colorectal cancer (CRC) screening due to patient preference and limited resources.[5] Among patients with an abnormal FIT result, the estimated CRC prevalence is 3.4%,[6] and missed or delayed diagnostic colonoscopy completion increases CRC-mortality.[7, 8] Therefore, the United States Multi-Society Task Force (USMSTF) recommends at least 80% of patients with an abnormal FIT result complete a diagnostic colonoscopy.[9] Despite this, the proportion of patients with an abnormal FIT result that complete a diagnostic colonoscopy varies significantly by health care setting and rarely exceeds 50% in most safety-net healthcare systems.[10, 11]

FIT is the primary form of CRC screening for average-risk adults ages 50–75 years in the San Francisco Health Network, a safety-net healthcare system. We previously reported diagnostic colonoscopy completion rates within one year of an abnormal FIT result ranged from 28%–76% across clinics.[11] Thus, the aim of this study was to identify the characteristics of clinical practices associated with higher diagnostic colonoscopy completion after an abnormal FIT result. These findings will help inform interventions to improve follow-up of abnormal FIT results and CRC outcomes in safety-net systems and other health care settings.

Methods

This cross-sectional survey study was performed in the San Francisco Health Network (SFHN). The SFHN is a multi-site integrated safety-net system comprised of community and hospital-based primary care clinics and one specialty referral center, the Zuckerberg San Francisco General Hospital (ZSFG), that care for approximately 90,000 assigned patients. SFHN clinics share an integrated electronic health record (EHR) platform, a clinical laboratory, and one Gastroenterology referral unit at ZSFG.

Process of Abnormal FIT follow-up

During the years prior to this study, SFHN primary care clinics could identify patients with abnormal FIT results within the EHR using local workflows or outside the EHR using i2i Population Health.[12] i2i Population Health is a panel management program that layers upon the EHR and can be used to create registries of patients due for CRC screening and follow-up of abnormal results. i2i Population Health is customizable to clinical sites and can include extraction of patient demographics, screening eligibility criteria, screening completion status, type of CRC screening test completed and result of laboratory tests. Some clinics used these mechanisms to generate quarterly lists of patients with abnormal FIT results. In these instances, patient lists supplemented primary care provider workflows, including electronic referrals to gastroenterology,[13] to ensure abnormal FIT follow-up.

Study Population

This study was approved by the University of California, San Francisco’s (UCSF) institutional review board (IRB #14–14861). Primary care team members from 11 SFHN clinics were approached and agreed to participate in the survey study. Team members primarily included Medical Directors, Physicians (attendings, residents, fellows), Nurses, and Medical Assistants.

Survey Development

We developed 5 versions of a survey questionnaire with the assistance of providers and staff familiar with the infrastructure of the SFHN clinics. The questionnaires were developed for: 1) Physicians/Nurses, 2) Medical Directors, 3) Nurse Managers, 4) Medical Assistants, and 5) Others (data analysts, quality improvement members, volunteers). Survey questions were tailored to the different roles and responsibilities of team members in the clinics (Appendix).

Nurse Managers, data analysts, quality improvement members, and volunteers were asked questions to understand the differences in follow-up of abnormal FIT results between clinics. Additionally, Nurse Managers were asked who was responsible for communicating abnormal FIT results to patients and details about patient registries, if present, including who was responsible for maintaining the registry and who was responsible for navigating patients to colonoscopy completion. All team members were asked about perceived clinic-level and patient-level barriers to diagnostic colonoscopy completion and patient-level navigation activities to improve colonoscopy completion for abnormal FIT results. In response to all questions, participants had the option of selecting no response, selecting multiple responses (with the exception of yes/no questions), or entering free-text if no best option was available on the survey. Our final survey took approximately 5–10 minutes to complete.

Data Collection

We distributed surveys from January 2017 to April 2017 during all-staff clinic meetings and sent electronic surveys to those not in attendance. After initial distribution, participants received up to three electronic reminders from our study team to complete the survey questionnaire. Results were stored in Qualtrics®.

Data Analysis

We reported descriptive statistics (proportions) for team members that completed the survey and their responses. We also reported proportions for follow-up of abnormal FIT results for the 11 clinics prior to the survey (May 2015 to April 2016); allowing at least 1 year after an abnormal FIT result for diagnostic colonoscopy completion. Based on consensus between authors (RBI and MS), clinics with <45% follow-up colonoscopy completion were categorized as lower-performing clinics and clinics with >60% follow-up colonoscopy completion were categorized as higher-performing clinics (Table 3). We assessed differences in practices in a grouped analysis comparing the four highest performing clinics (H, I, J, K) to the three lowest performing clinics (A, B, C) using chi-square analysis when appropriate. We used Stata/SE (version 14.0; StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA) statistical software for all analyses. All authors had access to the study data and reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Results

Survey Respondents

SFHN clinic characteristics by patients, providers who saw ≥20 patients aged 50–75, and CRC screening is included in Table 1. We identified 501 primary care team members, in which 343 (68.5%) completed the survey. The primary role of care team members who completed the survey is summarized in Table 2. Colonoscopy completion for patients with abnormal FIT results in the year preceding the survey study varied from 24.7% to 66.0% (Table 3).

Table 1:

Number of primary care providers, patients and payor mix of patients age 50–75

| Clinic | Providers* | Patients | Medi-Cal | Medicare |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | 18 | 2637 | 60% | 18% |

| B | 16 | 1036 | 41% | 37% |

| C | 9 | 1638 | 50% | 14% |

| D | 7 | 1473 | 43% | 15% |

| E | 7 | 1997 | 37% | 15% |

| F | 63 | 3968 | 38% | 19% |

| G | 7 | 1703 | 33% | 12% |

| H | 64 | 3566 | 35% | 27% |

| I | 8 | 2156 | 24% | 6% |

| J | 7 | 3129 | 27% | 15% |

| K | 7 | 1473 | 31% | 10% |

Number of providers who saw ≥20 patients aged 50–75

Table 2:

Primary role of care team members who completed survey

| Primary Role | Clinic Totals by Role n (%) |

|---|---|

| Attending Physician/Resident/Fellow | 127 (37.0%) |

| Nurse/Nurse Practitioner/Physician Assistant | 83 (24.2%) |

| Medical Assistant | 82 (23.9%) |

| Medical Director | 19 (5.5%) |

| Data Analyst/Quality Improvement/Volunteer | 15 (4.4%) |

| Nurse Manager | 10 (2.9%) |

| Other** | 7 (2.0%) |

| Total | 343 |

Behavioral Health Counselor; Clerical Supervisor; Health Educator/Coach; Medical Records; Practice Manager

Table 3:

Follow-up colonoscopy, provider communication and staff-reported registry by clinic

| Clinic | Abnormal FIT results (n) | Follow-up colonoscopy (%) | Provider communicating abnormal FIT result | Clinic-based registry* |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | 77 | 24.7 | -- | No |

| B | 46 | 39.1 | P | No |

| C | 41 | 41.5 | N | No |

| D | 37 | 46.0 | P, N | Yes |

| E | 43 | 51.2 | P, N | Yes |

| F | 101 | 51.5 | P | No |

| G | 57 | 56.1 | N | Yes |

| H | 93 | 62.4 | P, N, M | Yes |

| I | 35 | 62.9 | P, N, M | Yes |

| J | 113 | 65.5 | N, M | No |

| K | 47 | 66.0 | N, M | Yes |

P- Physician; N-Nurse; M-Medical Assistant

at least one clinic-staff report existence of FIT positive registry

Characteristics of higher and lower performing clinics

In response to perceived clinic-level differences between higher vs. lower-performing clinics, all nurse managers in the four higher-performing clinics (H–K) identified at least two team members who were responsible for communicating abnormal FIT results to patients. In the three lower-performing clinics (A–C), one nurse manager did not complete the survey (clinic A), while other nurse managers (n=2) identified the ordering physician (clinic B) or a nurse (clinic C) as the only team member responsible for communicating abnormal FIT results to patients. Nurse managers in higher-performing clinics consistently identified a medical assistant as one of the two individuals responsible for communicating these results (Table 3).

Based on roles and responsibilities, nurse managers, data analysts, quality improvement members, volunteers, and others (n=29) were asked if their clinics created a registry to track patients from abnormal FIT results responded. until diagnostic colonoscopy completion, 86% (25/29) Compared to the four highest performing clinics (H–K), the majority of team members from the three lowest performing clinics (A–C) answered ‘No’ when asked if their clinics created a registry to track FIT positive patients (29% vs. 100%, p<0.01); 71% of team members from the higher-performing clinics confirmed they had a registry. When Nurse Managers that reported having a registry of FIT positive patients (n=5) were asked who was responsible for maintaining the registry, the answers were variable and included the following: nurses on the patient’s care team, nurses not on the patient’s care team, medical assistant on the patient’s care team, data analyst, and patient’s primary care physician (PCP). The same nurse managers were also asked if there was an individual responsible for navigating patients to colonoscopy; again, the answers varied and included the following: nurses on the patient’s care team, nurses not on the patient’s care team, medical assistant on the patient’s care team, data analyst, and patient’s PCP.

Perceived barriers

In response to perceived clinic-level barriers to diagnostic colonoscopy completion, 325 participants contributed the following: 65% (210/325) cited inadequate resources to address patient barriers (e.g., lack of clinic resources to provide transportation), 21% (166/325) cited communication challenges (e.g., difficulty contacting patient by telephone and language barriers) and 46% (150/325) cited other competing health issues within their patient population. Compared to higher-performing clinics, lower-performing clinics more frequently reported inadequate resources (72% vs. 55%, p=0.02) and competing health issues (56% vs. 40%, p=0.03) in their patient populations. There was no difference in perceived communication challenges between higher- and lower-performing clinics (50% vs. 45%, p=0.53) (Table 4).

Table 4:

Most common perceived patient- and clinic-level barriers and patient-level navigation activities in lower- and higher-performing clinics

| Lower-performing clinics | Higher-performing clinics | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Perceived clinic-level barriers | |||

| Inadequate resources | 72% | 55% | 0.02 |

| Communication challenges | 50% | 45% | 0.53 |

| Other competing health issues | 56% | 40% | 0.03 |

| Perceived patient-level barriers | |||

| Fear of colonoscopy | 65% | 69% | 0.53 |

| Concerns about bowel prep | 51% | 43% | 0.22 |

| Colonoscopy not a priority | 59% | 37% | <0.01 |

| Patient-level navigation activities | |||

| Discuss colonoscopy at clinic visit | 83% | 61% | <0.01 |

| Patient education | 75% | 73% | 0.72 |

| Appointment reminders via telephone or mailed letters | 53% | 62% | 0.22 |

In response to perceived patient-level barriers to diagnostic colonoscopy completion, 330 participants reported the following: 62% (203/330) cited fear of colonoscopy, 48% (157/330) cited patient concerns regarding bowel preparation, and 44% (145/330) noted colonoscopy was not a priority for their patients. Lower-performing clinics more frequently responded that colonoscopy was not a priority for their patients compared to higher-performing clinics (59% vs. 37%, p<0.01). However, there were no statistical differences noted in perceived patient fear of colonoscopy (65% vs. 69%, p=0.53) or concerns regarding bowel prep (51% vs. 43%, p=0.22) (Table 4).

Navigation activities

In response to patient-level navigation activities, 332 participants reported the following: 75% (250/332) discussed colonoscopy completion during clinic visits, 73% (244/332) provided patient education, and 39% (130/332) provided appointment reminders via telephone calls or mailed letters. Compared to higher-performing clinics, lower-performing clinics more frequently discussed colonoscopy completion during clinic visits (83% vs 61%, p<0.01), but there were no statistically significant differences in the use of patient education (75% vs 73%, p=0.72) or appointment reminders (53% vs. 62%, p=0.22), respectively (Table 4).

Discussion

In order to effectively reduce CRC-associated mortality, healthcare systems that utilize FIT-based CRC screening must monitor rates of diagnostic colonoscopy completion, evaluate system-level differences for this metric, and implement practices associated with effective follow-up of abnormal FIT results. To our knowledge, our study is the first to explore clinic-level factors associated with variable rates of FIT follow-up within a safety-net population. Through a survey of primary care team members, we identified three distinguishing trends in clinics with higher rates of diagnostic colonoscopy completion 1-year after an abnormal FIT result: (1) higher performing clinics utilized registries to track patients with abnormal FIT results until colonoscopy completion, (2) higher performing clinics assigned at least two team members who were responsible for communicating abnormal FIT results to patients, and (3) team members responsible for communicating FIT results consistently included a nurse and medical assistant.

Much has been published on EHR-abstracted factors associated with lack of diagnostic colonoscopy completion in patients with abnormal FIT results.[14, 15] However, due to limited information in the EHR, factors that have been described to date are often at the patient-level and include age, race, gender, insurance type, housing status, etc. Many of these factors are non-modifiable, so while these studies identify patient subgroups that may warrant further examination, they offer limited solutions about how to best increase diagnostic colonoscopy completion among patients with abnormal FIT results. Our paper extends the field by examining clinic-level practices that increase follow-up of abnormal FIT results in a large, diverse, urban community-based safety-net population. Our findings can also assist primary care programs to design staffing ratios, workflows, and trainings to better support colonoscopy completion in safety-net settings.

Diagnostic colonoscopy completion is a complex process that requires effective communication and coordination between patients (understanding the implications of the abnormal result, arranging procedural transportation, coordinating time away from work, coordinating access to a bathroom for those without housing), providers (primary care communication with specialists, prescribing bowel cleansing medications), and the health care system (appointment access, appropriately scheduling patients with the correct sedation, facilitating short procedural wait times).[16] General principles to improve tracking of abnormal results will likely also lead to improvements in abnormal FIT follow-up. In the primary care literature, simplifications including identifying individuals responsible for tracking abnormal results has been associated with improvements in test-tracking.[17, 18] In our study, clinics with colonoscopy completion rates of 60% or greater, consistently identified medical assistants as one of the two team members responsible for communicating abnormal FIT results to patients.

The most frequent navigation activity in lower-performing clinics was discussing colonoscopy completion during office visits. Due to delays in scheduling across most medical practices, preferentially discussing follow-up of abnormal FIT results in-person rather than by telephone or other modalities, can lead to delays in colonoscopy completion. A recent meta-analysis reported patients preferred verbal (telephone calls or face-to-face visits) communication when learning about cancer screening results.[19] While these studies did not distinguish between preferences for these verbal communication modalities, it suggests an opportunity to improve test result notification intervals through increased use of telephone calls.

Our survey revealed that competing health issues, potentially due to co-morbidities[11] and resource limitations,[20] impact follow-up of abnormal FIT results. Lower performing clinics more frequently noted competing health issues and inadequate resources to address complex social circumstances. As such, the factors that contribute to inadequate diagnostic colonoscopy completion in the SFHN and similar healthcare systems, are likely multifactorial with challenges across multiple levels of care that must be addressed. Additional qualitative studies in diverse and medically underserved patient populations, including patient and provider focus groups and semi-structured interviews, will enhance the knowledge gained in this area and contribute to the development of evidence-based interventions to improve diagnostic colonoscopy completion.

A recent publication highlighted several strategies adopted by Kaiser Permanente Northern California to improve abnormal FIT result follow-up.[21] Over a 10-year period, they hired additional personnel, mailed letters to patients, adopted quality metrics, created a central registry, designated an individual responsible for tracking patients, and standardized outreach. Over a 10-year period, these combined efforts improved colonoscopy completion within 1-year of an abnormal FIT result from 73% to 85%. Our study extends these findings by highlighting three interventions that can be adopted by less-resourced health care systems that frequently utilize FIT for CRC screening.

Our study has several potential limitations. First, there could be inconsistencies in responses to certain questions if team members incorrectly assumed other team members’ functions. Second, the number of participants that identified the presence of a registry in the highest performing clinic (K), likely skewed the impact of this intervention in our study. Yet, we believe the potential of this intervention is supported by other recent studies.[21] Third, due to the nature of survey studies, our ability to interrogate observed patterns (for example, since lower-performing clinics more frequently discussed abnormal FIT results in-clinic, did higher-performing clinics more frequently utilize telephone or other modalities of communication) and free-text responses that might have provided further clarity was limited. Finally, the factors we identified associated with higher-performing clinics will require validation through additional testing. We hope to explore the themes discovered from this survey in future patient and provider focus groups and semi-structured interviews. Such inquiry will inform future testing of interventions in a randomized or pragmatic trial.

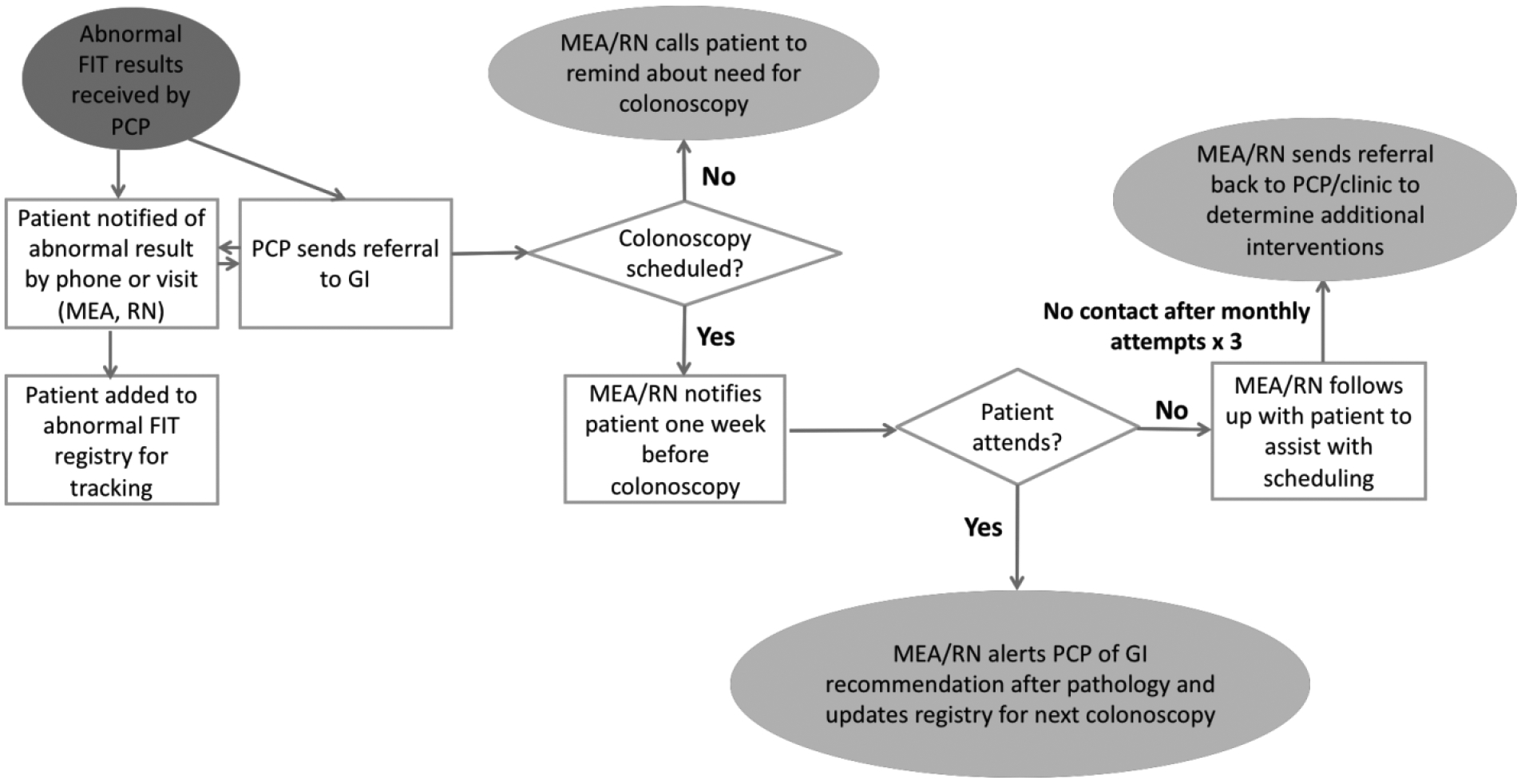

In conclusion, three clinic-level factors in our study were associated with higher diagnostic colonoscopy completion rates: utilizing registries to track patients with abnormal FIT results until diagnostic colonoscopy completion, assigning at least two team members to communicate abnormal FIT results to patients, and ensuring non-physician providers are an integral part of the team responsible for communicating FIT results. Our study findings may be useful to other integrated healthcare systems, particularly safety-net healthcare systems that care for racial/ethnic minorities, low-income patients, and other medically underserved populations. Taken together, selecting multi-component interventions that address patient barriers identified in the EHR, increasing utilization of non-physician providers (e.g., system-level navigators for chronic diseases and abnormal results), and adopting best practices from higher performing clinics as identified in this survey study (Figure 1) may improve diagnostic colonoscopy rates in patients with abnormal FIT results beyond any single intervention.

Figure 1:

Recommended process map for abnormal FIT follow-up

MEA: Medication Evaluation Assistant; RN: Registered Nurse; PCP: Primary Care Physician; GI: Gastroenterologist; FIT: Fecal Immunochemical Test

Funding:

This research was supported by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases of the National Institutes of Health T32DK007007 (RBI), the Dean M. Craig Endowed Chair of Gastrointestinal Medicine (MS), SF Cancer Initiative (MS), and the Center for Disease Control and Prevention U48 DP004998 (MS). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Abbreviations:

- CRC

colorectal cancer

- FIT

fecal immunochemical test

- SFHN

San Francisco Health Network

- EHR

Electronic Health Record

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited peer-reviewed manuscript that has been accepted for publication but has not been copyedited or corrected. The official version of record that is published in the journal is kept up to date and so may therefore differ from this version.

Conflict of Interest Disclosure Statement: The authors declare no potential conflicts of interest.

References:

- 1.Heitman SJ, Hilsden RJ, Au F, Dowden S, Manns BJ. Colorectal cancer screening for average-risk North Americans: an economic evaluation. PLoS Med. 2010;7(11):e1000370. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mandel JS, Bond JH, Church TR, Snover DC, Bradley GM, Schuman LM et al. Reducing mortality from colorectal cancer by screening for fecal occult blood. Minnesota Colon Cancer Control Study. N Engl J Med. 1993;328(19):1365–71. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199305133281901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Liss DT, Baker DW. Understanding current racial/ethnic disparities in colorectal cancer screening in the United States: the contribution of socioeconomic status and access to care. Am J Prev Med. 2014;46(3):228–36. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2013.10.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gupta S, Tong L, Allison JE, Carter E, Koch M, Rockey DC et al. Screening for colorectal cancer in a safety-net health care system: access to care is critical and has implications for screening policy. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2009;18(9):2373–9. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-09-0344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Inadomi JM, Vijan S, Janz NK, Fagerlin A, Thomas JP, Lin YV et al. Adherence to colorectal cancer screening: a randomized clinical trial of competing strategies. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172(7):575–82. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2012.332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jensen CD, Corley DA, Quinn VP, Doubeni CA, Zauber AG, Lee JK et al. Fecal Immunochemical Test Program Performance Over 4 Rounds of Annual Screening: A Retrospective Cohort Study. Ann Intern Med. 2016. doi: 10.7326/M15-0983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Corley DA, Jensen CD, Quinn VP, Doubeni CA, Zauber AG, Lee JK et al. Association Between Time to Colonoscopy After a Positive Fecal Test Result and Risk of Colorectal Cancer and Cancer Stage at Diagnosis. JAMA. 2017;317(16):1631–41. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.3634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee YC, Fann JC, Chiang TH, Chuang SL, Chen SL, Chiu HM et al. Time to Colonoscopy and Risk of Colorectal Cancer in Patients With Positive Results From Fecal Immunochemical Tests. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;17(7):1332–40 e3. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2018.10.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Robertson DJ, Lee JK, Boland CR, Dominitz JA, Giardiello FM, Johnson DA et al. Recommendations on Fecal Immunochemical Testing to Screen for Colorectal Neoplasia: A Consensus Statement by the US Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer. Gastroenterology. 2017;152(5):1217–37 e3. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2016.08.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chubak J, Garcia MP, Burnett-Hartman AN, Zheng Y, Corley DA, Halm EA et al. Time to Colonoscopy after Positive Fecal Blood Test in Four U.S. Health Care Systems. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2016;25(2):344–50. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-15-0470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Issaka RB, Singh MH, Oshima SM, Laleau VJ, Rachocki CD, Chen EH et al. Inadequate Utilization of Diagnostic Colonoscopy Following Abnormal FIT Results in an Integrated Safety-Net System. Am J Gastroenterol. 2017;112(2):375–82. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2016.555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.i2i Population Health. i2i Population Health 2020. https://www.i2ipophealth.com. Accessed January 27 2020.

- 13.Chen AH, Murphy EJ, Yee HF, Jr. eReferral--a new model for integrated care. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(26):2450–3. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1215594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.May FP, Yano EM, Provenzale D, Brunner J, Yu C, Phan J et al. Barriers to Follow-up Colonoscopies for Patients With Positive Results From Fecal Immunochemical Tests During Colorectal Cancer Screening. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;17(3):469–76. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2018.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Martin J, Halm EA, Tiro JA, Merchant Z, Balasubramanian BA, McCallister K et al. Reasons for Lack of Diagnostic Colonoscopy After Positive Result on Fecal Immunochemical Test in a Safety-Net Health System. Am J Med. 2017;130(1):93 e1–e7. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2016.07.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zapka JM, Edwards HM, Chollette V, Taplin SH. Follow-up to abnormal cancer screening tests: considering the multilevel context of care. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2014;23(10):1965–73. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-14-0454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.White B Four principles for better test-result tracking. Fam Pract Manag. 2002;9(7):41–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Elder NC, McEwen TR, Flach JM, Gallimore JJ. Creating Safety in the Testing Process in Primary Care Offices. In: Henriksen K, Battles JB, Keyes MA, Grady ML, editors. Advances in Patient Safety: New Directions and Alternative Approaches (Vol. 2: Culture and Redesign). Advances in Patient Safety. Rockville (MD: )2008. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Williamson S, Patterson J, Crosby R, Johnson R, Sandhu H, Johnson S et al. Communication of cancer screening results by letter, telephone or in person: A mixed methods systematic review of the effect on attendee anxiety, understanding and preferences. Prev Med Rep. 2019;13:189–95. doi: 10.1016/j.pmedr.2018.12.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cannin LW B Specialty Care in the Safety Net: Efforts to Expand Timely Access. California Health Care Foundation, Oakland, CA. 2009. https://www.chcf.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/PDF-SpecialtyCareOverview.pdf. Accessed November 1 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Selby K, Jensen CD, Zhao WK, Lee JK, Slam A, Schottinger JE et al. Strategies to Improve Follow-up After Positive Fecal Immunochemical Tests in a Community-Based Setting: A Mixed-Methods Study. Clin Transl Gastroenterol. 2019;10(2):e00010. doi: 10.14309/ctg.0000000000000010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]