Abstract

BACKGROUND

Several strategies have been proposed to determine onset of puberty without examination by a trained professional. This study sought to evaluate a novel approach to determine onset of puberty in girls.

METHODS

This study utilized the Cincinnati cohort of the Breast Cancer and the Environment Research Program. Girls were recruited at 6–7 years of age and followed every six months in the initial six years, and annually thereafter. Breast maturation and foot length were performed at each visit by health professionals certified in those methods. Mothers were asked to provide the age that they believed their daughter’s shoe size increased more rapidly.

RESULTS

These analyses include 252 participants. Age at increase in shoe size was correlated to age at onset of puberty (r=.21) and increase in foot length (r=.24). The difference of reported age of increased shoe size was 0.46 years before breast development.

CONCLUSIONS

Reported increase in shoe size occurred somewhat earlier and was significantly correlated to age of breast development. These preliminary results suggest that mother’s report of increase in shoe size appear to be as accurate as reports of other indirect methods of determining onset of puberty, such as self- or maternal estimates of breast development.

INTRODUCTION

Determination of pubertal status, both absolute (current pubertal stage) and relative (early, on-time, or late relative to peers), is important for comparison with physiologic measures, as well as vulnerability to risk-taking behaviors. For example, laboratory parameters, such as alkaline phosphatase and hemoglobin, are impacted by pubertal status, and girls who mature earlier than their peers have a greater likelihood of mental health issues as well as engaging in risk-taking behaviors, such as tobacco and sexual activity, which may carry into their adult years.1–3 In addition, earlier pubertal timing is associated with greater risk of several adult morbidities, such as breast cancer (particularly premenopausal breast cancer)4 and insulin resistance and type-2 diabetes.5

Multiple methods have been used to determine pubertal status in both the clinical and research arenas. Dorn et al6 reviewed different approaches to evaluation of pubertal maturation and noted that researchers reported direct assessment by study staff as the single most frequently cited approach, although many studies reported “according to Tanner” without further specifying the technique used. The objective of this study was to compare a novel approach to determine the onset of puberty, using recalled changes in shoe size.

METHODS

This study utilized a subset of the Cincinnati puberty study cohort of the Breast Cancer and the Environment Research Program. Participants were recruited at 6–7 years of age and followed every six months in the initial six years and annually thereafter. The study protocol has been described in detail 7 and was approved by the Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Institutional Review Board.

Breast maturation was performed at every visit by a female advanced practice nurse or physician (clinician), trained and certified for this study, using the methods published by Marshall and Tanner,8 with the addition of breast palpation. Foot length was assessed at each visit by the clinician using the Brannock foot device® (Liverpool, NY), after trained and certified in that technique.

We surveyed parents of school-aged children not in the study to determine how to ask families about changes in shoe size, and incorporated their suggestions into the study survey. When study participants were 10–11 years of age (range, 9–13 years), we asked mothers of participants, “How old was your daughter when she began needing larger shoe sizes at a faster rate?”

Onset of puberty was defined by age at breast stage 2 (B2), as published previously.9 Foot size velocity was calculated by taking the difference in value between consecutive visits divided by length of time between those visits and then annualized. The age at increase in foot length was determined by the initial age when the annualized foot length increase exceeded 1.5 cm per year. Pearson correlation coefficients were calculated for comparisons of age at increase in foot length, age that shoe size increased, and age at breast stage 2. The Kappa statistic (κ statistic) was used to assess interrater agreement of the two reports when a mother reported age in change of shoe size at two different visits; the κ statistic evaluates observed agreement to that expected by chance alone.10

RESULTS

This study included 252 participants with a mother’s report regarding age that the shoe size increased. There were 2100 clinical observations with simultaneous foot length and breast maturation assessments performed on these participants. The majority of reports (228/252, 90.5%) regarding the age that shoe size increased were in the 24-month window around age of breast development. There were two reports from 17 mothers; difference in age of shoe size change was 0.24 years, and agreement was moderate (k=0.53).10 Two mothers misunderstood the question and reported that the age of shoe size increase was less than one year of age, and excluded from the analyses.

Age at onset of puberty was significantly different by race: 8.4 years in black and 9.2 years in white participants. The mean age of pubertal onset (regardless of race) was 8.77 years; the mean age of increase in foot length velocity was 8.95 years, and the estimated age that shoe size increased was 8.57 years. The correlation of increase in foot growth velocity with increase in shoe size was 0.26 (p < .0001) (Table 1).

Table 1:

Association of ages of breast development, of change in measured foot length, and of reported age of shoe size increase, Pearson correlation coefficients (probability value)

| Age-shoe size | Age pubertal onset | |

|---|---|---|

| Age-foot length | 0.243 (.0014) | .259 (<0.0001) |

| Age-shoe size | .205 (.0074) |

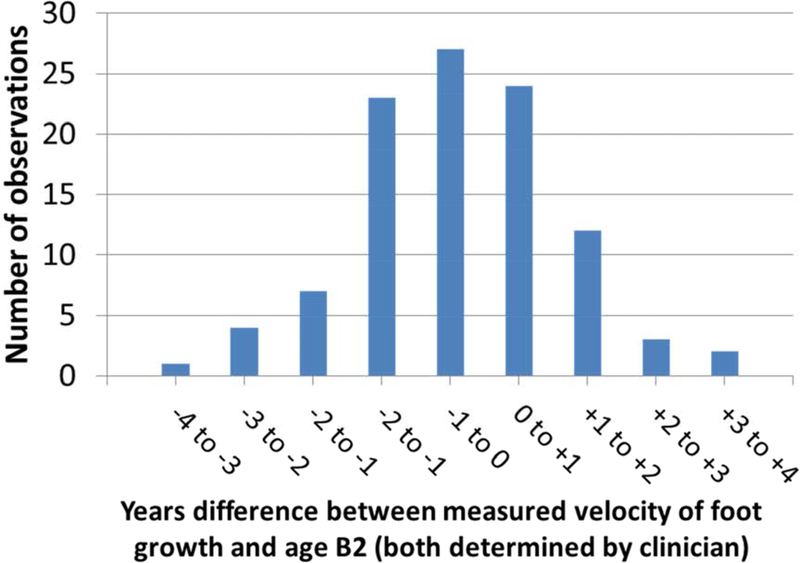

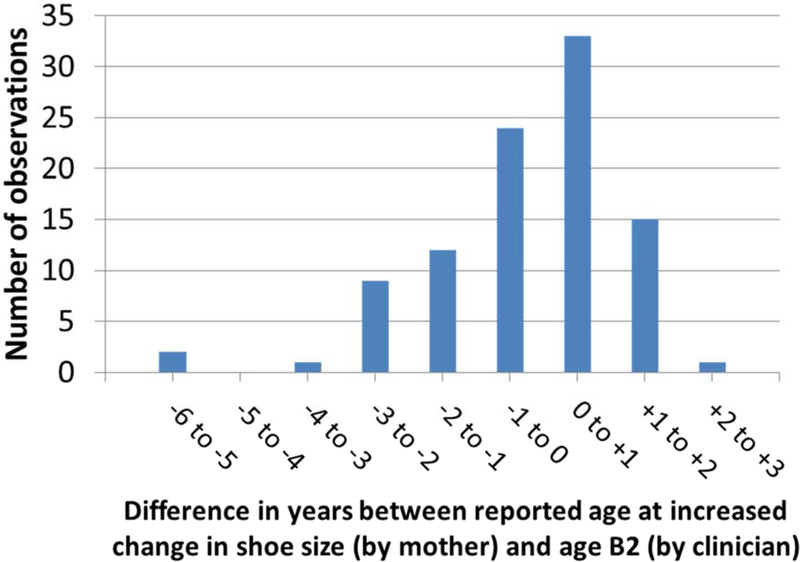

There was no significant difference in mean age of measured increase in foot length and age of pubertal onset in a given individual (Figure 1). The reported increase in shoe size was 0.46 years prior to age of B2 (Figure 2); the Pearson correlation between shoe size and age of pubertal onset was 0.21 and shoe size increase with actual increase in foot length was 0.24 (Table 1). In addition, 76% of the parent reports of age at increase in shoe size were within 12 months of the calculated increase in foot length (Figure 2).11–23

Figure 1.

Difference (years) between measured increased velocity of foot growth and age at breast development (B2);

x-axis: difference in years between measured foot length and age at B2; y-axis: number of observations

Figure 2.

Difference (years) between reported age at increased change in shoe size and age at breast development (B2);

x-axis: difference in years between reported age at increased change in shoe size (by mother) and age at B2 (by clinician); y-axis: number of observations

DISCUSSION

Tanner noted that the first evidence of pubertal development in girls is onset of the growth spurt, with limbs growing before the trunk and distal limbs prior to proximal limbs.24 We previously reported that the increase in foot length velocity and the pubertal growth spurt occurred at the same age and prior to breast stage 2.25 This observation led to the concept of this project, which was to ask mothers of our participants to estimate the age that their daughters had a noticeable increase in their shoe size. Two mothers misunderstood the question and provided the age that their daughters first wore shoes. Overall, the mother’s report of the noticeable shoe size increase occurred 0.46 years before the appearance of breast stage 2 development, consistent with Tanner’s observation, and correlated significantly with the actual increase in foot length. The increase in foot length and shoe size occurred concurrently with the previous report of increase in serum concentrations of estradiol in this cohort 6–12 months prior to B2.26 We found no previous reports in the literature of studies using foot size to assess pubertal maturation.

In addition to clinician assessment, there have been multiple approaches to estimate age at onset of puberty, including self- and parent assessment through line figures or photographs, scales examining several different pubertal milestones, and levels of sex hormones. Our results are somewhat lower but compare favorably to previous studies utilizing participant or parent assessment, which are summarized in Table 2. The majority of these studies either utilize line drawings, figures, and photographs; alternatively, scales were designed around a series of questions about pubertal milestones, such as the PDS (Pubertal Development Scale).27 The PDS is the most frequently used self-report method without figures or drawings; figures and drawings of breast and pubic hair have been regarded by some schools and parents as offensive.28 Our method has an advantage over the PDS in that there is minimal time and little apparent affiliation with puberty and sexual characteristics that might trouble parents of adolescents, but the disadvantage is that the only data obtained are associations with onset of breast development, and by inference, the onset of the pubertal growth spurt.25 Either of these associations would be useful to categorize a given individual as early/on-time/late maturation. Additionally, 76% of our participants entered puberty within 12 months of the reported increased velocity of shoe size change. Of note, the pubertal growth spurt in boys is a later pubertal event, but increase in shoe size should apply as well. Additionally, boys may have even greater reticence than girls for direct maturation assessment.

Table 2.

Studies examining alternates to direct pubertal assessment

| Authors (year) | # participants | Ages | Results |

|---|---|---|---|

| Duke, Litt (1980) | 43 | 9–17 | K=.81 BR (self, examiner) K=.91 PH (self, examiner) |

| Morris, Udry (1980) | 47 | 12–16 | R=.63 BR (self, examiner) R=.81 PH (self, examiner) |

| Brooks-Gunn (1987) | 151 | 11–13 | R=.52–.68 BR (self, examiner) R=.58–.74 PH (self, examiner) R=.69–.82 BR (mother, examiner) R=.57–.83 PH (mother, examiner) |

| Brooks-Gunn (1987) | 78–142 | 11–13 | R=.74–.75 (self, PDS) R=.54–.58 (examiner, PDS) |

| Hergenroeder (1999) | 107 | 8–17 | K=.35–.42 BR (self, examiner) K=.26–.44 PH (self, examiner) |

| Wu (2001) | 621 | 9–10 | K=.32–.51 BR (self, examiner) |

| Shirtcliff (2009) | 78 | 9–14 | K=.36 BR (self, examiner) K=.36 BR (examiner, PDS) K=.29 BR (self, PDS) |

| Desmangles (2006) | 130 | 11.3±3 | K=.49 BR (self, examiner) K=.68 PH (self, examiner) |

| Lamb (2011) | 115 | 8–18 | K=.81 BR (self, examiner) K=.78 PH (self, examiner) |

| Pereira (2014) | 481 | 6–9 | K=.10 BR (self, examiner) K=.70 (mother, examiner) |

| Jaruratanasirikul (2015) | 927 | 7–15 | K=.50 BR (self, examiner) K=.68 PH (self, examiner) |

| Rasmussen (2015) | 418 | 7.4–14.9 | K=.28 BR (self, examiner) K=.55 PH (self, examiner) K=.28 BR (mother, examiner) K=.41 PH (mother, examiner) |

| Terry (2016) | 282 | 6–15 | K=.66 BR (self, mother) K=.38 BR (self, examiner) K=.46 BR (mother, examiner) |

| Chavarro (2017) | 131 | 10.3±1.7 | R=.71 BR (self, examiner) R=.89 BR (self, ‘true’ status) R=.80 BR (examiner, ‘true’ status) |

BR = breast stage

K = kappa statistic

R = correlation coefficient

PDS = Peterson Developmental Scale

PH = pubic hair stage

To avoid the confusion, we noted with responses from two mothers, we would recommend revising the question to read, “Since entering kindergarten, how old was your daughter when she began needing larger shoe sizes at a faster rate?” Of note, we used assessment by the health professional as the standard, although the recent study by Chavarro, using a method of triads, which incorporated self- and physician-assessment of maturation status with average hormone ranks, noted self-assessment may be superior to physician assessment.23

This study provides a new methodologic approach to determine pubertal onset in girls (B2) that is brief and straightforward and provides a similar degree of accuracy as many of the published studies. We are not proposing to replace direct clinician assessment, which is still considered the gold standard, but offer this straightforward question as a noninvasive tool to assess pubertal onset in research studies.

Acknowledgments

We would like to gratefully acknowledge the research staff, study helpers, participants and their families, and the clerical assistance of Jan Clavey.

Funding Sources: Funded through the Breast Cancer and the Environment Research Centers grant U01 ES/CA ES-019453 from the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (NIEHS), the National Cancer Institute (NCI); UL1 RR026314 (USPHS), P30 ES006096 (NIEHS), and 8 UL1 TR000077–05 (NIH and CTSA).

Funded through the Breast Cancer and the Environment Research Centers grant U01 ES/CA ES-12770 from the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (NIEHS), the National Cancer Institute (NCI); UL1 RR026314 (USPHS), P30 ES006096 (NIEHS), and 8 UL1 TR000077–05 (NIH and CTSA).

Funded through the Breast Cancer and the Environment Research Centers ES-12770 from the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (NIEHS) and National Cancer Institute (NCI); UL1 RR026314 (USPHS), P30 ES006096 (NIEHS), and UL1 TR000077–05 (NIH).

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Financial Disclosure: The authors have no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

- 1.Smith AR, Chein J, Steinberg L. Impact of socio-emotional context, brain development, and pubertal maturation on adolescent risk-taking. Horm Behav 2013;64(2):323–332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hoyt LT, Niu L, Pachucki MC, Chaku N. Timing of puberty in boys and girls: implications for population health. SSM Popul Health. 2020;10:100549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mendle J, Ryan RM, McKone KMP. Age at menarche, depression, and antisocial behavior in adulthood. Pediatrics. 2018;141(1). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Clavel-Chapelon F Differential effects of reproductive factors on the risk of pre-and postmenopausal breast cancer: results from a large cohort of French women. Br J Cancer. 2002;86(5):723–727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cheng TS, Day FR, Lakshman R, Ong KK. Association of puberty timing with type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Med. 2020;17(1):e1003017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dorn LD, Dahl RE, Biro F. Defining the boundaries of early adolescence: a user’s guide to assessing pubertal status and pubertal timing in research with adolescents. Appl Devel Sci. 2006;10(1):30–56. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Biro FM, Galvez MP, Greenspan LC, Succop PA, Vangeepuram N, Pinney SM, Teitelbaum S, Windham GC, Kushi LH, Wolff MS. Pubertal assessment method and baseline characteristics in a mixed longitudinal study of girls. Pediatrics. 2010;126(3):e583–590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Marshall WA, Tanner JM. Variations in pattern of pubertal changes in girls. Arch Dis Child. 1969;44:291–303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Biro FM, Greenspan LC, Galvez MP, Pinney SM, Teitelbaum S, Windham GC, Deardorff J, Herrick RL, Succop PA, Hiatt RA, Kushi LH, Wolff MS. Onset of breast development in a longitudinal cohort. Pediatrics. 2013;132(6):1019–1027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Landis JR, Koch GG. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics. 1977;33(1):159–174. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Duke PM, Litt IF, Gross RT. Adolescents’ self-assessment of sexual maturation. Pediatrics. 1980;66(6):918–920. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Morris NM, Udry JR. Validation of a self-administered instrument to assess stage of adolescent development. J Youth Adolesc. 1980;9(3):271–280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brooks-Gunn J, Warren MP, Rosso J, Gargiulo J. Validity of self-report measures of girls’ pubertal status. Child Dev 1987;58(3):829–841. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hergenroeder AC, Hill RB, Wong WW, Sangi-Haghpeykar H, Taylor W. Validity of self-assessment of pubertal maturation in African American and European American adolescents. J Adolesc Health. 1999;24(3):201–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wu Y, Schreiber GB, Klementowicz V, Biro F, Wright D. Racial differences in accuracy of self-assessment of sexual maturation among young black and white girls. J Adolesc Health. 2001;28(3):197–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shirtcliff EA, Dahl RE, Pollak SD. Pubertal development: correspondence between hormonal and physical development. Child Dev. 2009;80(2):327–337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Desmangles JC, Lappe JM, Lipaczewski G, Haynatzki G. Accuracy of pubertal Tanner staging self-reporting. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab. 2006;19(3):213–221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lamb MM, Beers L, Reed-Gillette D, McDowell MA. Feasibility of an audio computer-assisted self-interview method to self-assess sexual maturation. J Adolesc Health. 2011;48(4):325–330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pereira A, Garmendia ML, González D, Kain J, Mericq V, Uauy R, Corvalán C. Breast bud detection: a validation study in the Chilean Growth Obesity Cohort Study. BMC Womens Health. 2014;14:96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jaruratanasirikul S, Kreetapirom P, Tassanakijpanich N, Sriplung H. Reliability of pubertal maturation self-assessment in a school-based survey. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab. 2015;28(3–4):367–374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rasmussen AR, Wohlfahrt-Veje C, Tefre dR-MK, Hagen CP, Tinggaard J, Mouritsen A, Mieritz MG, Main KM. Validity of self-assessment of pubertal maturation. Pediatrics. 2015;135(1):86–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Terry MB, Goldberg M, Schechter S, Houghton LC, White ML, O’Toole K, Chung WK, Daly MB, Keegan TH, Andrulis IL, Bradbury AR, Schwartz L, Knight JA, John EM, Buys SS. Comparison of clinical, maternal, and self pubertal assessments: implications for health studies. Pediatrics. 2016;138(1):e20154571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chavarro JE, Watkins DJ, Afeiche MC, Zhang Z, Sanchez BN, Cantonwine D, Mercado-Garcia A, Blank-Goldenberg C, Meeker JD, Tellez-Rojo MM, Peterson KE. Validity of self-assessed sexual maturation against physician assessments and hormone levels. J Pediatr. 2017;186:172–178.e173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tanner JM. Growth at adolescence. 2 ed. Oxford, England: Blackwell Scientific Publications; 1962. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ford KR, Khoury JC, Biro FM. Early markers of pubertal onset: height and foot size. J Adolesc Health. 2009;44(5):500–501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Biro FM, Pinney SM, Huang B, Baker ER, Walt Chandler D, Dorn LD. Hormone changes in peripubertal girls. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2014;99(10):3829–3835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Petersen AC, Crockett L, Richards M, Boxer A. A self-report measure of pubertal status: reliability, validity, and initial norms. J Youth Adolesc. 1988;17(2):117–133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Susman EJ, Dorn LD, Schiefelbein VL. Puberty, sexuality, and health In: Lerner RM, Easterbrooks MA, Mistry J, eds. Handbook of Psychology. Vol 6 Hoboken, NJ: Wiley; 2003:295–324. [Google Scholar]