Abstract

Our group previously demonstrated that M-protein light chain (LC) glycosylation can be detected on routine MASS-FIX testing. Glycosylation is increased in patients with immunoglobulin light chain amyloidosis (AL) and rarely changes over the course of a patient’s lifetime. To determine the rates of progression to AL and other plasma cell disorders (PCDs), we used residual serum samples from the Olmsted monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance (MGUS) screening cohort. Four-hundred and fourteen patients with known MGUS were tested by MASS-FIX, and 25 (6%) were found to have glycosylated light chains (LCs). With a median follow-up of surviving patients of 22.2 years, the 20-year progression rates to a malignant PCD were 67% (95% CI 29%, 84%) and 13% (95% CI 9%, 18%) for patients with and without glycosylated LCs, respectively. The risk of progression was independent of Mayo MGUS risk score. The respective rates of progression to AL at 20-years were 21% (95% CI 0.0, 38%) and 3% (95% CI 0.6%, 5.5%). In summary, monoclonal LC glycosylation is a potent risk factor for progression to AL, myeloma, and other PCDs, an observation which could lead to earlier diagnoses and potentially reduced morbidity and mortality.

INTRODUCTION

Pathogenic glycosylation of proteins has been implicated in various hematological malignancies, often with prognostic associations.1 It has been postulated that glycosylation also has a pathogenic effect on immunoglobulin light chains (LCs) and that glycosylated LCs could be more prone to be amyloidogenic.2 We demonstrated previously that monoclonal LCs of patients with kappa restricted immunoglobulin light chain amyloidosis (AL) are N-glycosylated at a rate nearly 13-fold higher than the kappa LCs of patients with monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance (MGUS), multiple myeloma (MM), and assorted plasma cell disorders (PCDs)3, 4 and that N-glycosylation of monoclonal LCs starts at the MGUS stage, predating the diagnosis of AL amyloidosis by years to decades.5

These observations prompted the hypothesis that the finding of an N-glycosylated monoclonal LC as part of a diagnosis of MGUS heightens the risk for progression to AL. This post-translational modification is easily recognized with routine use of MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry, our standard method for detecting monoclonal proteins at the Mayo Clinic.6, 7 Since we had previously demonstrated that the patterns seen on routine MALDI-TOF, which we had presumed was N-glycosylation, were indeed N-glycosylation through both deglycosylation experiments4 and cDNA sequencing demonstrating somatic mutations to N-glycosylation consensus sequences (manuscript in progress), for the purposes of this manuscript, the N-glycosylation patterns seen on routine MALDI-TOF were deemed sufficient to call N-glycosylation for the purpose of this study. Using the Olmsted MGUS cohort, a well characterized population of patients screened for MGUS as part of an epidemiologic study,8 we set out to define the rate of progression of N-glycosylated MGUS to AL and other PCDs.

METHODS

The samples and participants were taken from the Olmsted County MGUS epidemiology project.8 In brief, this was a study in which residents of Olmsted County over the age of 50 years of age as of 1995 were invited to participate. Samples were analyzed from 21,463 of 28,038 enumerated residents. In that study 3.2% were found to have MGUS by serum protein electrophoresis screening.8 A follow-up study employing remaining baseline samples using the FreeLite assay to screen for monoclonal gammopathies revealed that the actual prevalence of MGUS including LC MGUS was 4.2%.9 Residual samples within 2 years of diagnosis were available for testing for 414 of the positive patients with MGUS, and this comprised our study population. This study was approved by the Mayo Clinic Institutional Review Board in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Samples were run on MASS-FIX as follows.6, 7 The immuno-enrichment was performed as previously described by adding 10 μL aliquot of serum to 50μL agarose beads coupled with one of the single domain antibodies specific for heavy chains (HC) of IgM, IgA, IgG and LC of κ or λ constant domains (Thermo Fischer Scientific), washed, reduced, spotted, and analyzed separately on MALDI-TOF-MS (Microflex LT, Bruker). The spectra from each five immuno-enrichment of each sample were overlaid, and LC m/z distribution was visually inspected for the presence of peaks in [M+1H]1+ and [M+2H]2+ using in house developed software and categorized patient’s monoclonal LC as either N-glycosylated or not N-glycosylated with no knowledge of their follow-up status.

Demographics were taken from the time of the date of the MGUS diagnosis. P values for differences between continuous variables were calculated using two-sample t-tests and nominal variables using chi-square tests. Survival and progression rates were calculated according the Kaplan-Meier method. The cumulative incidence of progression accounting for the competing risk of death was calculated using the method of Putter, et al.10 The association of progression and glycosylation was evaluated using Cox proportional hazards regression. All analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC).

RESULTS

Of the 414 individuals included in this study, 25 patients (6%) had N-glycosylation of their MGUS light chains. Demographics and baseline characteristics are shown in Table 1. Patients without and with N-glycosylated monoclonal proteins were similar in terms of age, gender, hemoglobin, serum creatinine, M-spike, involved FLC, and involved to uninvolved FLC. The N-glycosylation group was more likely to have an abnormal FLC ratio and to have a lower urine total protein. Sixty-four percent (16/25) of the N-glycosylated group had a kappa restricted monoclonal gammopathy, which was no different from the group without N-glycosylation. Overall, there was no difference in MGUS risk11 between the two groups.

Table 1.

Patient characteristicsa

| Characteristic | No N-glycosylation (n=389) | N-glycosylation (N=25) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Days sample from MGUS dx | 319 (−636, 729) | 272 (0, 723) | 0.778 |

| Male gender, n (%) | 192 (49) | 14 (56) | 0.52 |

| Age, years | 69.0 (39.0, 98.0) | 69.0 (54.0, 87.0) | 0.885 |

| Hemoglobin, g/dL | 13.8 (8.1, 17.4) | 12.8 (9.3, 15.8) | 0.143 |

| Creatinine, mg/dL | 1.1 (0.5, 5.7) | 1.1 (0.9, 1.7) | 0.788 |

| Serum M-protein, g/L | 6 (0, 29) | 5 (0, 27) | 0.759 |

| Serum M-protein >=15 g/L, n (%) | 92 (24.1) | 6 (26.1) | 0.828 |

| Heavy chain isotype Ig G / IgA or IgM, n (%) | 278 (72) / 111 (28) | 20 (80) / 5 (20) | 0.357 |

| Light chain kappa, n (%) | 241 (62) | 16 (64) | 0.838 |

| iFLC, mg/Lb | 19 (1.0, 1650) | 28 (9.0, 911) | 0.217 |

| iFLC/uFLC (n=216)b | 1.5 (0.0, 258) | 2.3 (0.1, 98.5) | 0.230 |

| Abnormal FLC ratio, n (%)b | 112 (30.1) | 12 (52.2) | 0.027 |

| Urine protein g/24 hours (n=68) | 0.10 (0, 1.9) | 0.10 (0.0, 0.2) | 0.028 |

| High | 15 (4.1) | 1 (4.8) |

Unless otherwise indicated, represented in median and range

FLC missing at diagnosis in 22 patients

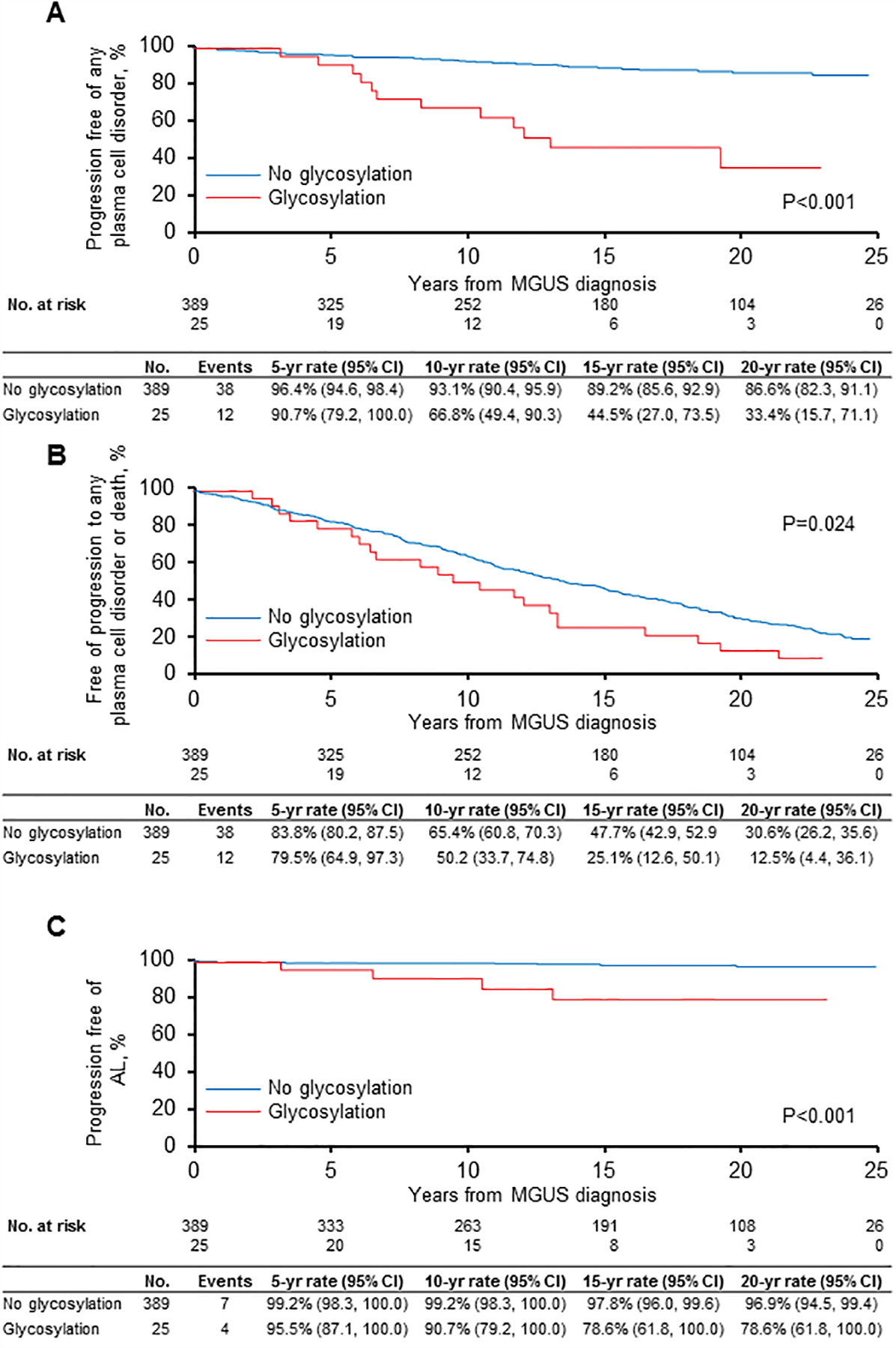

As of July 31, 2019, there were 11 AL progressions across the groups, 50 other PCD progressions (Table 2), and 324 deaths. Overall, there were more progressions in the N-glycosylated group 48% (12/25) versus 10% (38/389). With a median follow-up of surviving patients of 21.9 years among patients diagnosed with MGUS, Kaplan-Meier estimates at 20 years for progression to a malignant PCD was 66.6% (95% CI 28.9%, 84.3%) for patients with N-glycosylation of their monoclonal LCs and 13.4% (95% CI 8.9%, 17.7%) for patients without N-glycosylation of their monoclonal LCs (Figure 1a). The respective cumulative incidence of progression to a malignant PCD at 20 years accounting for competing risk of death was 50.2% (95% CI 33.7, 74.8) and 9.4% (95% CI 6.9%, 12.8%) (Figure 1b). The relative risk of progression was 6.4 (95% CI 3.3, 12.4) on univariate analysis and 7.8 (95%CI 4.0, 15.3) on multivariable analysis including the Mayo MGUS risk score11 (Table 3).

Table 2.

PCD progression diagnoses

| Not N-glycosylated N=389 |

N-glycosylated N=25 |

HR (95% CI) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No progression, n (%) | 351 (90) | 13 (52) | NA | NA |

| Progression to PCD, n (%)a | 38 (10) | 12 (48) | 6.4 (3.3, 12.4) | <0.001 |

| AL amyloidosis, n (%) | 7 (1.8) | 4 (16) | 10.1 (2.9, 34.7) | <0.001 |

| Multiple myeloma, n (%) | 25 (6.4) | 5 (20) | 3.8 (1.4, 9.9) | 0.007 |

| Waldenstrom macroglobulinemia and other LPDs, n (%) | 5 (1.3) | 1 (4.0) | 4.3 (0.5, 38.6) | 0.192 |

| Other LPDs with a monoclonal IgM, n (%) | 1 (0.3)a | 2 (8.0)b | 33.1 (3.0, 365.2) | 0.004 |

LPD, lymphoproliferative disorder; PCD, plasma cell disorder

SLL. Antecedent rheumatoid arthritis

Both with cold agglutinin disease; one of two with unexplained progressive pulmonary hypertension with right-sided heart failure diagnosed 3 years prior to his death increased LV filling pressures increased RVSP, pulmonary hypertension, atrial fibrillation, ascites requiring paracentesis. Patient was ever tested for AL.

Figure 1.

Rates of progression based on N-glycosylation status of the monoclonal light chains

a. Progression to any plasma cell disorder or lymphoproliferative disorder

b. Progression to any plasma cell disorder lymphoproliferative disorder with competing risk of death

c. Progression to AL amyloidosis

Table 3.

Univariate and multivariate for progression and death

| Univariate | Multivariable | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome | Risk factor | Level | N | Events | HR (95% CI) | p-value | (95% CI) | p-value |

| Progression to any PCD | Glycosylation | No glycosylation | 389 | 38 | Reference | Reference | ||

| Glycosylation | 25 | 12 | 6.4 (3.3, 12.4) | <0.001 | 7.8 (4.0, 15.3) | <0.001 | ||

| Mayo Risk Group11 | 0 factors | 161 | 11 | Reference | Reference | |||

| Any 1 factor | 144 | 13 | 1.4 (0.6, 3.2) | 0.398 | 1.2 (0.5, 2.7) | 0.648 | ||

| Any 2 factors | 63 | 13 | 3.7 (1.6, 8.2) | 0.002 | 3.2 (1.4, 7.2) | 0.005 | ||

| Any 3 factors | 16 | 10 | 13.3 (5.0, 31.4) | <0.001 | 13.4 (5.6, 32.0) | <0.001 | ||

| Progression or death | Glycosylation | No glycosylation | 389 | 307 | Reference | Reference | ||

| Glycosylation | 25 | 22 | 1.6 (1.1, 2.5) | 0.027 | 1.6 (0.99, 2.5) | 0.051 | ||

| Mayo Risk Group11 | 0 factors | 161 | 118 | Reference | Reference | |||

| Any 1 factor | 144 | 117 | 1.2 (0.9, 1.5) | 0.224 | 1.2 (0.9, 1.5) | 0.267 | ||

| Any 2 factors | 63 | 56 | 1.4 (1.03, 2.0) | 0.033 | 1.4 (1.02, 1.9) | 0.041 | ||

| Any 3 factors | 16 | 15 | 1.7 (0.98, 2.9) | 0.060 | 1.7 (0.98, 2.9) | 0.060 | ||

Mayo risk factors for progression from MGUS to myeloma and related conditions:11 free light chain ratio abnormal, M-spike ≥ 1.5, heavy chain isotype not IgG

The incidence of AL at 20 years was 21.4% (95% CI 0.0, 38.2%) for patients with glycosylated monoclonal LCs and 3.1% (95% CI 0.6%, 5.5%) for patients without glycosylation (Figure 1c). The cumulative incidence of AL amyloidosis accounting for competing risk of death was 16.7% (95% CI 6.8%, 40.9%) and 1.9% (95% CI 0.9%, 3.9%), respectively (data not shown). Excluding AL progressions, estimates at 20 years for progression to a malignant PCD were 89.4% (95% CI 85.7%, 93.3%) for patients with N-glycosylation of their monoclonal LCs and 47.6% (95% CI 24.6%, 92.2%) for patients without N-glycosylation of their monoclonal LCs.

None of the patients with N-glycosylated LCs who progressed to PCDs other than amyloidosis was specifically tested for AL amyloidosis with Congo red staining of their tissues. It is notable that 2 of the patients with N-glycosylation who progressed to a lymphoproliferative disorder both had cold agglutinin disease, a finding that complements another interesting observation made by our group regarding increased rates of N-glycosylation among patients with cold-agglutinin disease.12

DISCUSSION

This study confirmed our hypothesis that patients with glycosylated LCs have a higher likelihood of developing AL over time with a hazard ratio of 10.1 (95% CI 2.9, 34.7), an observation that could be rationalized biochemically.13–17 The finding that the risk of progression to other PCDs was also higher among patients with N-glycosylated LCs was unexpected. Could the higher progression rate among non-AL PCD patients be a function of latent AL causing symptoms bringing patients with myeloma or other PCDs to medical attention for AL symptoms, which were not recognized as such, but attributed to the other PCD? Alternatively, LC glycosylation might reflect the increase in inflammation seen with aging and in some autoimmune diseases.18 Therefore, these patients could represent a biologically older group with higher levels of immune dysregulation.

These data support the recommendation that patients with apparent MGUS (or any other PCD) and N-glycosylation discovered on routine MASS-FIX be screened for AL with a minimum of an AL review of systems, a Congo red of the bone marrow and of the fat, an NT-proBNP, and a test for albuminuria.19 Follow-up among these patients with MGUS (or smoldering PCDs) would be in line with that recommended for high-risk MGUS.

In summary, the recognition that glycosylated monoclonal light chains pose a risk for progression could lead to earlier diagnoses of AL and other PCDs, which could translate into reduced morbidity and mortality.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS:

This research was supported by Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN, US NIH CA186781, The Predolin Foundation, The JABBS Foundation.

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST: David Murray and Surendra Dasari have intellectual property rights to the MASS-FIX assay and patents. The other authors have no conflicts related to this work.

REFERENCES

- 1.Pinho SS, Reis CA. Glycosylation in cancer: mechanisms and clinical implications. Nat Rev Cancer 2015. September; 15(9): 540–555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bellotti V, Mangione P, Merlini G. Review: immunoglobulin light chain amyloidosis--the archetype of structural and pathogenic variability. J Struct Biol 2000. June; 130(2–3): 280–289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Milani P, Murray DL, Barnidge DR, Kohlhagen MC, Mills JR, Merlini G, et al. The utility of MASS-FIX to detect and monitor monoclonal proteins in the clinic. Am J Hematol 2017. August; 92(8): 772–779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kumar S, Murray D, Dasari S, Milani P, Barnidge D, Madden B, et al. Assay to rapidly screen for immunoglobulin light chain glycosylation: a potential path to earlier AL diagnosis for a subset of patients. Leukemia 2019. January; 33(1): 254–257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kourelis T, Murray DL, Dasari S, Kumar S, Barnidge D, Madden B, et al. MASS-FIX may allow identification of patients at risk for light chain amyloidosis before the onset of symptoms. Am J Hematol 2018. August 13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mills JR, Kohlhagen MC, Willrich MAV, Kourelis T, Dispenzieri A, Murray DL. A universal solution for eliminating false positives in myeloma due to therapeutic monoclonal antibody interference. Blood 2018. August 9; 132(6): 670–672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mills JR, Kohlhagen MC, Dasari S, Vanderboom PM, Kyle RA, Katzmann JA, et al. Comprehensive Assessment of M-Proteins Using Nanobody Enrichment Coupled to MALDI-TOF Mass Spectrometry. Clin Chem 2016. October; 62(10): 1334–1344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kyle RA, Therneau TM, Rajkumar SV, Larson DR, Plevak MF, Offord JR, et al. Prevalence of monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance. The New England journal of medicine 2006. March 30; 354(13): 1362–1369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dispenzieri A, Katzmann JA, Kyle RA, Larson DR, Melton LJ 3rd, Colby CL, et al. Prevalence and risk of progression of light-chain monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance: a retrospective population-based cohort study. Lancet 2010. May 15; 375(9727): 1721–1728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Putter H, Fiocco M, Geskus RB. Tutorial in biostatistics: competing risks and multi-state models. Stat Med 2007; 26: 2389–2430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rajkumar SV, Kyle RA, Therneau TM, Melton LJ 3rd, Bradwell AR, Clark RJ, et al. Serum free light chain ratio is an independent risk factor for progression in monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance. Blood 2005. August 1; 106(3): 812–817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sidana S, Murray DL, Dasari S, Go R, Willrich MA, Snyder M, et al. Glycosylation of Immunoglobulin Light Chains is Highly Prevalent in Cold Agglutinin Disease Submitted. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Dwulet FE, O’Connor TP, Benson MD. Polymorphism in a kappa I primary (AL) amyloid protein (BAN). Mol Immunol 1986. January; 23(1): 73–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Toft KG, Sletten K, Husby G. The amino-acid sequence of the variable region of a carbohydrate-containing amyloid fibril protein EPS (immunoglobulin light chain, type lambda). Biol Chem Hoppe Seyler 1985. July; 366(7): 617–625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stevens FJ. Four structural risk factors identify most fibril-forming kappa light chains. Amyloid 2000. September; 7(3): 200–211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dasari S, Theis JD, Vrana JA, Meureta OM, Quint PS, Muppa P, et al. Proteomic detection of immunoglobulin light chain variable region peptides from amyloidosis patient biopsies. J Proteome Res 2015. April 3; 14(4): 1957–1967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Connors LH, Jiang Y, Budnik M, Theberge R, Prokaeva T, Bodi KL, et al. Heterogeneity in primary structure, post-translational modifications, and germline gene usage of nine full-length amyloidogenic kappa1 immunoglobulin light chains. Biochemistry 2007. December 11; 46(49): 14259–14271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gudelj I, Lauc G, Pezer M. Immunoglobulin G glycosylation in aging and diseases. Cell Immunol 2018. November; 333: 65–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gertz MA. Immunoglobulin light chain amyloidosis diagnosis and treatment algorithm 2018. Blood Cancer J 2018. May 23; 8(5): 44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]