Abstract

Background:

Visual conformity with affirmed gender (VCAG) or “passing” is thought to be an important, but poorly understood, determinant of well-being in transgender people. VCAG is a subjective measure that is different from having an inner sense of being congruent with one’s gender identity.

Aim:

We examined the frequency and determinants of VCAG and explored its association with mental health outcomes in a cohort of transgender adults.

Methods:

The “Study of Transition, Outcomes & Gender (STRONG)” is a cohort of transgender individuals recruited from three Kaiser Permanente health plans located in Georgia, Northern California and Southern California. A subset of cohort members completed a survey between 2015 and 2017. VCAG was assessed as the difference between two scales: Scale 1 reflecting the person’s sense of how they are perceived by others; and Scale 2 reflecting the person’s desire to be perceived. Participants were considered to have achieved VCAG when their Scale 1 scores were equal to or exceeded their Scale 2 scores. The frequency of VCAG and their independent associations with anxiety and depression symptoms were explored using data from 556 survey respondents including 273 transwomen and 283 transmen. Based on self-described gender identity, none of the participants identified as non-binary or gender fluid.

Outcomes:

VCAG, depression and anxiety.

Results:

VCAG was achieved in 28% of transwomen and 62% of transmen and was more common in persons who reported greater sense of acceptance and pride in their gender identity as measured on the Transgender Congruence Scale. Another factor associated with greater likelihood of VCAG was receipt of gender affirming surgery, but the association was only evident among transmen. Participants who achieved VCAG had a lower likelihood of depression and anxiety with prevalence ratios (95% confidence intervals) of 0.79 (0.65, 0.96) and 0.67 (0.46, 0.98), respectively.

Clinical Implications:

VCAG may serve as an important outcome measure following gender affirming therapy

Strengths and Limitations:

Strengths of this study include a well-defined sampling frame and use of a novel patient-centered outcome of interest. Cross-sectional design and uncertain generalizability of results are the limitations.

Conclusion:

These results, once confirmed by prospective studies, may help better characterize the determinants of well-being in the transgender community, facilitating the design of interventions to improve the well-being and quality of life of this vulnerable population.

INTRODUCTION

The term ‘transgender’ refers to an individual whose gender identity and/or gender expression differs from the male or female sex designation recorded at birth.1,2 Systematic reviews of the literature have demonstrated that transgender persons experience disproportionately high rates of depression and anxiety compared to members of the general population.3-5 Some of the factors that may explain mental health problems among transgender people, including limited access to care, minority distress and history of discrimination, are will described; however, additional quantitative data capable of closing the remaining knowledge gaps are needed.3,6,7

It has been proposed that mental health in transgender persons may be related to the ability to affirm their gender identity. . Some transgender persons seek to affirm their gender through hormone therapy or surgery to achieve desired femininity or masculinity.1,8 Hormone therapy can include estrogens and antiandrogens for transwomen (i.e., transgender people whose sex was assigned as male at birth) or testosterone for transmen (i.e., those assigned female sex at birth).9 Gender affirming surgery (GAS) may include a range of procedures aimed at surgical alteration of the genitalia and secondary sex traits.10 A number of studies have linked gender affirming treatment and especially GAS to improved mental health status and quality of life.11-18

As gender congruence is an important goal of GAS, measuring gender congruence is important in transgender health research. One widely used measure is the Transgender Congruence Scale (TCS), which quantifies two factors congruence related to appearance and congruence related to acceptance of gender identity.19 Higher TCS scores were previously found to be positively associated with the extent of GAS receipt and inversely related to symptoms of depression and Anxiety.19,20

The well-being of some transgender people may also be influenced by a person’s feeling of how they may be perceived by others – i.e. ‘passing’. We describe ‘passing’ as ‘visual conformity with affirmed gender ' (VCAG) and propose using it as a marker of social affirmation that is different from TCS, which is designed to measure inner sense of being congruent with one’s gender identity. To this end, this study seeks to explore prevalence and determinants of VCAG as well its association with mental health outcomes in a cohort of transgender adults. We hypothesize that transgender persons who achieved VCAG will be less likely to experience symptoms of anxiety and depression, independent of other factors, including TCS.

METHODS

Study Participants

The present study uses the cohort of participants from the Study of Transition, Outcomes, and Gender (STRONG) recruited from three Kaiser Permanente health plans located in Georgia, Northern California, and Southern California. These 3 integrated health care systems provide comprehensive health services to approximately 8 million members. Enrollees are sociodemographically diverse and broadly representative of the communities in the corresponding areas.21

The three KP organizations use similar electronic health record systems and have comparably organized databases with identical variable names, formats, and specifications across sites. The study was conducted in partnership with Emory University, which served as the coordinating center, and all activities were reviewed and approved by the institutional review boards of the 4 participating institutions.

The methods of cohort ascertainment were described in detail previously.22,23 Briefly, electronic medical record data for all participating health plan members of all ages enrolled between January 1, 2006, and December 31, 2014, were used to identify supporting evidence for transgender/gender non-conforming status based on relevant International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision codes (e.g., 302.5 – transsexualism, and V45.77 +121141596 - acquired absence of genital organs: history of sex reassignment surgery); and presence of specific keywords (e.g. ‘transgender’, ‘transsexual’, or ‘gender identity’) in free-text notes. Eligibility status was independently verified by two trained reviewers with disagreements adjudicated by a committee that included the project manager and two investigators. As not all data elements of interest could be ascertained from the electronic medical record data alone, the project also included a cross-sectional survey that collected self-reported information from a subset of cohort members.

Survey Recruitment

The survey eligibility criteria included: age 18 years or older, current enrollment in one of the participating health systems, and at least one relevant diagnostic code, and text stringconfirming transgender status in the electronic health records. Participants were excluded from the survey if their transgender-related encounters were limited to mental health services; their physicians did not provide consent for initiating the contact; or, in their responses to the screening questions, their gender identity was the same as sex recorded at birth. All initial survey invitations were sent via regular mail. The letter included a web site address and a unique password linked to the study identification number; participants were asked to read and electronically sign the consent form online prior to survey initiation. An option to fill out a paper survey was also available; however only 38 study participants (5% of all respondents) chose that option.

Survey Measures

Transgender status was confirmed based on a 2-step question: first inquiring about participants’ sex assigned at birth and then asking about their current gender identity. If the gender identity was different from the assigned female sex the participant was considered transmasculine; if the gender identity was different from the assigned male sex, the participant was considered transfeminine. Five persons who reported being born with intersex conditions were excluded from the current analysis. Each participant was further asked to self-identify using one of 49 commonly used gender identity terms that included wide range of both binary (e.g., ‘female’, ‘male’, ‘transgender man’ or ‘trans woman’) and non-binary (e.g., ‘androgyne’, ‘genderqueer’ or ‘two-spirit’) categories. If none of the 49 descriptors were deemed suitable, the participants also had an opportunity to identify as ‘other’ and write-in their own gender identity descriptors. In addition, each participant was asked about hormone therapy use and about history and type of GAS received to date. Participants were also asked about their history of procedures aimed at changing secondary sex characteristics such as laryngeal shave, facial feminization, and electrolysis.

To assess VCAG, participants were prompted with the following questions: “Assuming gender and gender expression are continuums, how do you think others perceive you on the scales below? Assuming gender and gender expression are continuums, how do you want others to perceive you on the scales below?” Each question was accompanied by two sliding gender-specific scales (male and female) ranging from 0 to 100. Participants were considered as having achieved VCAG when their scores assessing how others perceive them (Scale 1) were equal to or exceeded their desired scores (Scale 2). Inner sense of gender congruence was measured using the 12-item TCS instrument, which is distinct from VCAG because it is designed to assess self-acceptance; i.e., to what extent transgender individuals feel genuine, authentic, and comfortable with their identity and appearance.19 The TCS score was defined as high vs. low using study population’s median value as the cutoff.

Information about the participants’ depression and anxiety levels was collected using the 10-item Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D-10) and the Beck Anxiety Index (BAI), respectively. For depression and anxiety, the binary outcome was defined using the previously proposed clinically relevant general population cutoffs of ≥10 for CES-D-10, and >21 for BAI.24,25

If participants did not respond to all items in a given scale (CES-10, BAI or TCS) the missing responses at the item level were assigned based on multiple imputation methods (5 imputations) using fully conditional specification by means of the proc mi procedure in SAS. Variables used to impute missing values included available items from each scale, gender identity, age, race, education level, history of GAS, procedures to change secondary sex characteristics, and VCAG status.

Data analyses

The goals of the analyses were to examine the distribution of, and factors associated with, VCAG and to compare mental health status (expressed as prevalence estimates for CES-D-10, and BAI-derived depression and anxiety) in persons that had and had not achieved VCAG. Although survey respondents had an option of selecting more than one gender identity category, none of the individuals in the analysis dataset explicitly self-identified as having a non-binary or gender fluid identity. For this reason, all individuals were categorized as either transmen or transwomen. These associations were examined using multivariable log-binomial regression models. The covariates in the model included gender identity status, age in years, and extent of GAS or other procedures received. Based on reported history of GAS, each participant was placed in one of the following 4 ordered categories: (1) no GAS to date; (2) chest surgery (e.g., mastectomy or breast augmentation); (3) gonadectomy or hysterectomy without genital reconstruction (e.g., hysterectomy without vaginectomy or orchiectomy without vaginoplasty); and (4) definitive genital reconstruction (e.g., vaginectomy, vaginoplasty or other procedures aimed at changing the genitalia). The “no surgery” category (n=200) primarily included individuals who received hormone therapy (n=180) as well 20 participants who reported no gender affirming treatment at all; the second group was too small to be included as a separate analytic category. In addition, the analyses included a dichotomous variable reflecting receipt of procedures for changing secondary sex characteristics (e.g., laryngeal shave or facial electrolysis for transwomen and tattoos or “facial masculinization” for transmen). All models were examined for collinearity interactions between TF/TM status and each of the covariates in the model to assess if the analyses had to be conducted separately for TF and TM participants. The results of each model were expressed as adjusted prevalence ratios (PR) and the corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CI) calculated using proc genmod command with link=log option. All data analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina).

RESULTS

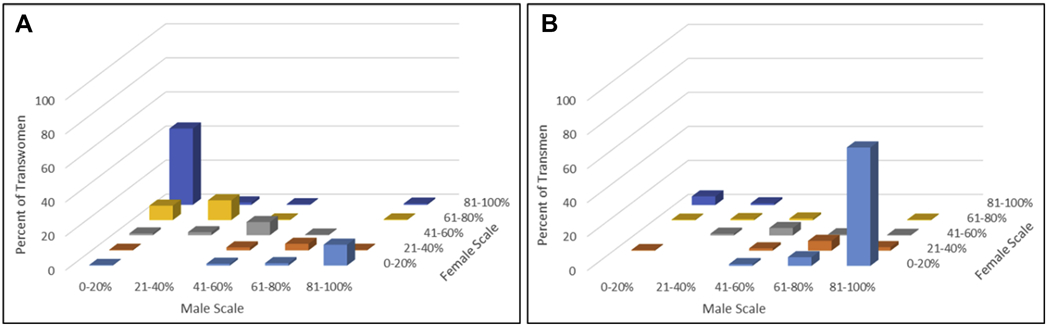

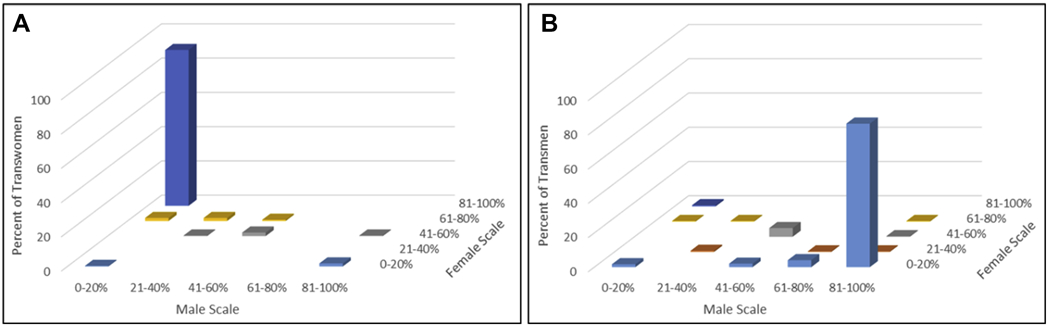

Of the 2,136 individuals invited to participate, 697 (33%) completed at least part of the survey and of those, 620 responded to VCAG related items. Figures 1 and 2 present participants’ reports of their current and desired gender identity and gender expression, as they thought they were perceived by others. Among transwomen, 91% reported a wish to be seen in the highest category of female identity, but only 45% felt that others would place them in that category. Among transmen, 84% reported a wish to be seen in the highest category of male identity, and 70% felt that others would place them in that category.

Figure 1.

Extent to which survey respondents believe others perceive them as a person of their desired gender among transwomen (Panel A) and transmen (Panel B) (“Assuming gender and gender expression represent a continuum, how do you think others perceive you on the scales below?”).

Figure 2.

Extent to which survey respondents want to be perceived by others as a person of their gender among transwomen (Panel A) and transmen (Panel B) (“Assuming gender and gender expression represent a continuum, how do you want others to perceive you on the scales below?”).

Table 1 compares the distributions of various participant characteristics by VCAG status. Compared to transwomen, transmen were more than twice as likely to report having achieved VCAG (62% vs. 28%). Among participants who reported no history of GAS, only 30% reported having achieved VCAG. The corresponding percentages for cohort members who reported receiving different types of GAS were substantially higher (range 48-58%). Persons who had significant depression and anxiety symptoms, as defined based on CES-D-10 BAI scores, were less likely to report having achieved VCAG compared to individuals who scored lower on each of these scales.

Table 1.

| Participant Characteristics | Achieved VCAG n (row %) |

Not achieved VCAG n (row %) |

Total n (column %) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender identity | |||

| Transwomen | 87 (28.2) | 222 (71.8) | 309 (49.8) |

| Transmen | 194 (62.4) | 117 (37.6) | 311 (50.2) |

| Age (years) | |||

| < 30 | 101 (49.8) | 102 (50.2) | 203 (32.7) |

| 30-39 | 72 (53.3) | 63 (46.7) | 135 (21.8) |

| 40-54 | 63 (41.2) | 90 (58.8) | 153 (24.7) |

| ≥55 | 45 (34.9) | 84 (65.1) | 129 (20.8) |

| History of gender affirming surgery | |||

| No Surgery | 72 (30.5) | 164 (69.5) | 236 (38.1) |

| Chest Surgery | 94 (58.4) | 67 (41.6) | 161 (26.0) |

| Gonadectomy or Hysterectomy | 44 (58.7) | 31 (41.3) | 75 (12.1) |

| Genital Reconstruction | 71 (48.0) | 77 (52.0) | 148 (23.9) |

| Transgender congruence scale | |||

| Below Median | 80 (29.4) | 192 (70.6) | 272 (43.9) |

| Above Median | 183 (59.0) | 127 (41.0) | 310 (50.0) |

| Missing information (imputed) | 18 (47.4) | 20 (52.6) | 38 (6.1) |

| Procedures to change secondary sex characteristics | |||

| Yes | 208 (45.2) | 252 (54.8) | 460 (74.2) |

| No | 73 (45.6) | 87 (54.4) | 160 (25.8) |

| CES-D-10 depression score c | |||

| ≥ 10 | 97 (36.5) | 169 (63.5) | 266 (42.9) |

| < 10 | 154 (52.6) | 139 (47.4) | 293 (47.3) |

| Missing information (imputed) | 30 (49.2) | 31 (50.8) | 61 (9.8) |

| BAI anxiety score d | |||

| > 21 | 34 (33.7) | 67 (66.3) | 101 (16.3) |

| ≤ 21 | 218 (48.1) | 235 (51.9) | 453 (73.1) |

| Missing information (imputed) | 29 (43.9) | 37 (56.1) | 66 (10.7) |

| All Subjects | 281 (45.3) | 339 (54.7) | 620 (100.0) |

Participants were considered as having achieved visual conformity with affirmed gender (VCAG) when their perceived scores were equal to or exceeded their desired scores

Percentages may not sum to 100 due to rounding

Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES-D-10): Comprised of 10 questions, the score range is 0-30, with higher scores indicating higher levels of depression

Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI): Comprised of 21 questions, the score range is 0-63, with higher scores indicating higher levels of anxiety

The results of multivariable analyses assessing factors associated with VCAG are presented in Table 2. As there was significant effect modification by gender identity, the results of these analyses are presented for separately for transmen and transwomen. The multivariable models demonstrated that higher TCS was associated with VCAG and the association was stronger among transwomen (PR = 5.04; 95% CI: 2.85, 8.92) than among transmen (PR = 1.37; 95% CI: 1.12, 1.67). Another factor associated with greater likelihood of VCAG was GAS receipt, but the association was only evident among transmen.

Table 2.

| Independent Variables | Transwomen |

Transmen |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PR | 95% CI | PR | 95% CI | |

| History of gender affirming surgery | ||||

| No Surgery | 1.00 | reference | 1.00 | reference |

| Chest Surgery | 1.34 | 0.67, 2.66 | 1.37 | 1.03, 1.83 |

| Gonadectomy or Hysterectomy | 0.48 | 0.13, 1.70 | 1.65 | 1.21, 2.25 |

| Genital Reconstruction | 0.98 | 0.68, 1.42 | 1.60 | 1.16, 2.21 |

| Transgender Congruence Score | ||||

| Low (below median) | 1.00 | reference | 1.00 | reference |

| High (above median) | 5.04 | 2.85, 8.92 | 1.37 | 1.12, 1.67 |

| Procedures to change secondary sex characteristics | ||||

| No | 1.00 | reference | 1.00 | reference |

| Yes | 0.92 | 0.60, 1.40 | 0.97 | 0.81, 1.17 |

| Age (years) | ||||

| < 30 | 1.00 | reference | 1.00 | reference |

| 30-39 | 0.99 | 0.56, 1.75 | 0.98 | 0.81, 1.19 |

| 40-54 | 0.89 | 0.53, 1.48 | 0.86 | 0.69, 1.08 |

| ≥ 55 | 0.98 | 0.62, 1.55 | 0.92 | 0.64, 1.32 |

Adjusted for all variables listed in the table; stratified by gender identity due to significant interaction

Participants were considered as having achieved visual conformity with affirmed gender (VCAG) when their current scores were equal to or exceeded their desired scores

Abbreviations:

PR: prevalence ratio

CI: confidence interval

Tables 3-4 present the results of the multivariable analyses assessing the associations of VCAG with depression (CES-D score >10) and anxiety (BAI score >21). There was no evidence that any of the associations were modified by gender identity. For this reason, the models for each outcome included all participants without stratification, and the results were adjusted for GAS, TCS, gender identity, receipt of procedures to change secondary sex characteristics, and age.

Table 3.

| Independent Variables | PR | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|

| Visual conformity with affirmed gender (VCAG) | ||

| Not achieved | 1.00 | reference |

| Achieved | 0.79 | 0.65, 0.96 |

| Transgender Congruence Score | ||

| Low (below median) | 1.00 | reference |

| High (above median) | 0.65 | 0.53, 0.79 |

| History of gender affirming surgery | ||

| No surgery | 1.00 | reference |

| Chest Surgery | 0.83 | 0.66, 1.05 |

| Gonadectomy or Hysterectomy | 0.89 | 0.68, 1.17 |

| Genital Reconstruction | 0.85 | 0.65, 1.12 |

| Procedures to change secondary sex characteristics | ||

| No | 1.00 | reference |

| Yes | 1.00 | 0.85, 1.18 |

| Gender identity | ||

| Transwomen | 1.00 | reference |

| Transmen | 1.00 | 0.83, 1.20 |

| Age (years) | ||

| < 30 | 1.00 | reference |

| 30-39 | 0.76 | 0.61, 0.96 |

| 40-54 | 0.71 | 0.57, 0.88 |

| ≥ 55 | 0.70 | 0.54, 0.91 |

Adjusted for all variables listed in the table

Defined as CES-D 10 score ≥ 10

Abbreviations:

PR: prevalence ratio

CI: confidence interval

Table 4.

| Independent Variables | PR | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|

| Visual conformity with affirmed gender (VCAG) | ||

| Not achieved | 1.00 | reference |

| Achieved | 0.67 | 0.46, 0.98 |

| Transgender Congruence Score | ||

| Low (below median) | 1.00 | reference |

| High (above median) | 0.54 | 0.36, 0.79 |

| History of gender affirming surgery | ||

| No surgery | 1.00 | reference |

| Chest Surgery | 0.78 | 0.52, 1.18 |

| Gonadectomy or Hysterectomy | 0.75 | 0.42, 1.35 |

| Genital Reconstruction | 0.44 | 0.21, 0.94 |

| Procedures to change secondary sex characteristics | ||

| No | 1.00 | reference |

| Yes | 1.14 | 0.79, 1.63 |

| Gender identity | ||

| Transwomen | 1.00 | reference |

| Transmen | 1.58 | 1.06, 2.35 |

| Age (years) | ||

| < 30 | 1.00 | reference |

| 30-39 | 0.49 | 0.29, 0.82 |

| 40-54 | 0.64 | 0.40, 1.03 |

| ≥ 55 | 0.39 | 0.19, 0.80 |

Adjusted for all variables listed in the table

Defined as BAI score > 21

Abbreviations:

PR: prevalence ratio

CI: confidence interval

As shown in Table 3, persons who achieved VCAG had a lower likelihood of depression (PR = 0.79; 95% CI: 0.65, 0.96). The association between depression and GAS receipt was not statistically significant. Higher TCS was also associated with lower prevalence of depression (PR = 0.65; 95% CI: 0.53, 0.79). There was no evidence that presence of depression symptoms differed in transmen and transwomen, or receipt of procedures to change secondary sex characteristics. Depressive symptoms were more common in younger study participants (under the age of 30 years) than in the older age groups.

The associations of both VCAG and higher TCS with anxiety were again inverse with PR (95% CI) estimates of 0.67 (0.46, 0.98) and 0.54 (0.36, 0.79), respectively. Transgender persons with history of genital reconstruction surgery lower prevalence of anxiety, than those who reported no history of GAS (PR=0.44; 95% CI: 0.21, 0.94). The association between age and anxiety was in the same direction as that observed for depression, but stronger (Table 4).

The analyses confirmed that TCS and VCAG, although related to each other, were not collinear (i.e., did not measure the same phenomenon). The condition index for these two variables ranged between 6 and 7; both estimates much lower than the conventional collinearity threshold of 30.26

DISCUSSION

We observed that transgender individuals who felt that others perceive them as having the gender with which they most strongly identified (denoted as VCAG) were significantly less likely to experience both depression and anxiety. These results were independent of the feeling of transgender congruence (as measured by TCS) and receipt of GAS, which have also been shown to improve mental well-being in the transgender community.27 Prior studies have described the influence of body-gender congruence on mental health by measuring feelings of authenticity with oneself or correlating psychometric testing with stages of gender confirmation therapies.13-19 To our knowledge, this is the first study to quantify the phenomenological experience of “passing” as an individual of the desired gender identity..28

We also observed that GAS receipt was associated with higher likelihood of having achieved VCAG, but this association was only evident in transmen, and not in transwomen. The reason for this observation are not clear, and should be explored further.

The desire to be recognized and affirmed by others as having the gender with which one most strongly identifies has been discussed previously.29-31 While body-gender congruence, self-acceptance, and VCAG are all closely inter-related, this study shows that subjective perception of VCAG is associated with better mental health status in a way that is independent of validated measures of body-gender congruence and/or treatment receipt.31

VCAG or “passing” can be a sensitive issue because it implies the need to conform to cis-normative binary gender.32 For some, the desire for “passing” originates not only from an internal need to mediate body-gender incongruence, but from external pressures to blend-in.28,33 Studies have shown that individuals who adopt cis-normative gender expressions are less likely to be victim to stigma, discrimination, and violence, which are known risk factors for depression, anxiety, and other psychopathology.34

Several limitations of the present study should be recognized. The cross-sectional design of the survey does not allow direct causal inferences. It is quite possible that the observed associations are bidirectional. For example, while transgender individuals who did not achieve VCAG are more likely to experience depression, it is also plausible that persons suffering from depression are less likely to feel unable to achieve VCAG. It is worth noting, however, that there are studies suggesting that increased visibility as a transgender individual, whether through self-disclosure or being “visibly trans”, increases risk of mental health problems, including suicide ideation and self-harm attempts.35,36 As is the case with most cross-sectional surveys, the less than optimal response rate raises concerns about systematic differences between respondents and those who chose to participate in the survey. This limitation also calls for a longitudinal study that involves periodic assessment of VCAG along with other variables. The survey eligibility criteria, which required presence of both a relevant diagnostic code, and a confirmatory text, as well as consent by a physician resulted in a study group comprised exclusively of people who self-identified as trans men or trans women with almost all participants (96%) receiving hormone therapy. For this reason, the analytic dataset in this study did not include persons with non-binary gender identities and did not allow assessing if hormone therapy alone was associated with VCAG.

Questions related to VCAG were proposed by the STRONG stakeholder advisory group who considered them as high-priority. These survey items were extensively pilot tested; however, they have not been previously validated in a different population and require further evaluation. We also recognize that transgender individuals enrolled through Kaiser Permanente health systems represent a cohort of individuals who are insured and therefore may not be representative of the broader transgender population in the United States.

CONCLUSION

The results from the present study provide evidence that VCAG status or “passing” is not only associated with self-acceptance as measured by TCS, but is an independent predictor of depression and anxiety. These findings require confirmation using prospective study designs. If confirmed, the results of observational studies can then be used to design individual or community-based interventions aimed at improving the well-being of transgender people. Such interventions should consider possible influence of VCAG or “passing” and will require multidimensional approaches geared towards increasing body-gender congruence, and developing strategies to strengthen transgender resilience.

Acknowledgements:

Funding sources for this work included Contract AD-12-11-4532 from the Patient Centered Outcome Research Institute and Grant R21HD076387 from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: None

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Coleman E, Bockting W, Botzer M, et al. Standards of Care for the Health of Transsexual, Transgender, and Gender-Nonconforming People, Version 7. Int J Transgender 2012;13:165–232. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Institute of Medicine. The Health of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender People: Building a Foundation for Better Understanding. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2011. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bariola E, Lyons A, Leonard W, Pitts M, Badcock P, Couch M. Demographic and Psychosocial Factors Associated With Psychological Distress and Resilience Among Transgender Individuals. Am J Public Health 2015;105:2108–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Owen-Smith A, Sineath RC, Sanchez T, et al. Perception of Community Tolerance and Prevalence of Depression among Transgender Persons. J Gay Lesbian Ment Healt 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nuttbrock L, Bockting W, Rosenblum A, et al. Gender abuse and major depression among transgender women: a prospective study of vulnerability and resilience. Am J Public Health 2014;104:2191–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dhejne C, Van Vlerken R, Heylens G, Arcelus J. Mental health and gender dysphoria: A review of the literature. Int Rev Psychiatry 2016;28:44–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Reisner SL, Poteat T, Keatley J, et al. Global health burden and needs of transgender populations: a review. Lancet 2016;388:412–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Feldman J, Brown GR, Deutsch MB, et al. Priorities for transgender medical and healthcare research. Curr Opin Endocrinol Diabetes Obes 2016;23:180–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Safer JD, Tangpricha V. Care of Transgender Persons. N Engl J Med 2019;381:2451–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Berli JU, Knudson G, Fraser L, et al. What Surgeons Need to Know About Gender Confirmation Surgery When Providing Care for Transgender Individuals: A Review. JAMA surgery 2017;152:394–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gomez-Gil E, Zubiaurre-Elorza L, Esteva I, et al. Hormone-treated transsexuals report less social distress, anxiety and depression. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2012;37:662–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lindgren TW, Pauly IB. A body image scale for evaluating transsexuals. Arch Sex Behav 1975;4:639–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gorin-Lazard A, Baumstarck K, Boyer L, et al. Hormonal therapy is associated with better self-esteem, mood, and quality of life in transsexuals. J Nerv Ment Dis 2013;201:996–1000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Murad MH, Elamin MB, Garcia MZ, et al. Hormonal therapy and sex reassignment: a systematic review and meta-analysis of quality of life and psychosocial outcomes. Clin Endocrinol 2010;72:214–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lindqvist EK, Sigurjonsson H, Mollermark C, Rinder J, Farnebo F, Lundgren TK. Quality of life improves early after gender reassignment surgery in transgender women. Eur J Plast Surg 2017;40:223–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Papadopulos NA, Lelle JD, Zavlin D, et al. Quality of Life and Patient Satisfaction Following Male-to-Female Sex Reassignment Surgery. J Sex Med 2017;14:721–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ainsworth TA, Spiegel JH. Quality of life of individuals with and without facial feminization surgery or gender reassignment surgery. Qual Life Res 2010;19:1019–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Colizzi M, Costa R, Todarello O. Transsexual patients' psychiatric comorbidity and positive effect of cross-sex hormonal treatment on mental health: results from a longitudinal study. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2014;39:65–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kozee HB, Tylka TL, Bauerband LA. Measuring Transgender Individuals' Comfort With Gender Identity and Appearance: Development and Validation of the Transgender Congruence Scale. Psychol Women Q 2012;36:179–96. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Owen-Smith AA, Gerth J, Sineath RC, et al. Association Between Gender Confirmation Treatments and Perceived Gender Congruence, Body Image Satisfaction, and Mental Health in a Cohort of Transgender Individuals. J Sex Med 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Koebnick C, Langer-Gould AM, Gould MK, et al. Sociodemographic characteristics of members of a large, integrated health care system: comparison with US Census Bureau data. Perm J 2012;16:37–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Roblin D, Barzilay J, Tolsma D, et al. A novel method for estimating transgender status using electronic medical records. Ann Epidemiol 2016;26:198–203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Quinn VP, Nash R, Hunkeler E, et al. Cohort profile: Study of Transition, Outcomes and Gender (STRONG) to assess health status of transgender people. BMJ Open 2017;7:e018121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Beck AT, Epstein N, Brown G, Steer RA. An inventory for measuring clinical anxiety: psychometric properties. Journal of consulting and clinical psychology 1988;56:893–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yi MS, Mrus JM, Wade TJ, et al. Religion, spirituality, and depressive symptoms in patients with HIV/AIDS. J Gen Intern Med 2006;21 Suppl 5:S21–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hair JF, Black WC, Babin BJ, Anderson RE, Tatham RL. Multivariate data analysis. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Owen-Smith AA, Gerth J, Sineath RC, et al. Association Between Gender Confirmation Treatments and Perceived Gender Congruence, Body Image Satisfaction, and Mental Health in a Cohort of Transgender Individuals. J Sex Med 2018;15:591–600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.White Hughto JM, Clark KA, Altice FL, Reisner SL, Kershaw TS, Pachankis JE. Creating, reinforcing, and resisting the gender binary: a qualitative study of transgender women's healthcare experiences in sex-segregated jails and prisons. Int J Prison Health 2018;14:69–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.van de Grift TC, Kreukels BP, Elfering L, et al. Body Image in Transmen: Multidimensional Measurement and the Effects of Mastectomy. J Sex Med 2016;13:1778–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dubov A, Fraenkel L. Facial Feminization Surgery: The Ethics of Gatekeeping in Transgender Health. Am J Bioeth 2018;18:3–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Goldstein Z, Ting J, Rhodes R. Faces Matter. Am J Bioeth 2018;18:10–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lombardi EL, Wilchins RA, Priesing D, Malouf D. Gender violence: transgender experiences with violence and discrimination. J Homosex 2001;42:89–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.White Hughto JM, Reisner SL, Pachankis JE. Transgender stigma and health: A critical review of stigma determinants, mechanisms, and interventions. Soc Sci Med 2015;147:222–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Grant J, Mottet L, Tanis J, Harrison J, Herman J, Keisling M. Injustice at Every Turn: A Report of the National Transgender Discrimination Survey. https://www.transequality.org/sites/default/files/docs/resources/NTDS_Report.pdf Accessed 03/06/2020 Washington, DC: National Center for Transgender Equality and National Gay and Lesbian Task Force; ; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bauer GR, Scheim AI, Pyne J, Travers R, Hammond R. Intervenable factors associated with suicide risk in transgender persons: a respondent driven sampling study in Ontario, Canada. BMC Public Health 2015;15:525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Haas AP, Eliason M, Mays VM, et al. Suicide and suicide risk in lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender populations: review and recommendations. J Homosex 2011;58:10–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]