Abstract

Idiopathic spinal cord herniation is a rare cause of progressive myelopathy that can result in severe disability. In the following report, an illustrative case and associated video in the surgical management of ventral thoracic spinal cord herniation is presented and discussed. Spinal cord herniation is most commonly observed in the thoracic spine and is characterized by ventral displacement of the spinal cord through a defect in the dura. Over time ventral herniation of the spinal cord can compromise its vascular perfusion, resulting in further ischemic injury. The etiology is unclear, but suspected to be either acquired or congenital. Multiple surgical techniques have been reported with the goal in detethering the cord and taking adjunctive measures in reducing the risk for reherniation. Surgical management of thoracic spinal cord herniation carries great risks, however neurological outcomes are generally favorable with improvements reported in the majority of cases.

Keywords: Spine surgery, spinal cord injury, myelopathy, Brown Sequard syndrome, Operative technique, Neuroradiology, Dural repair

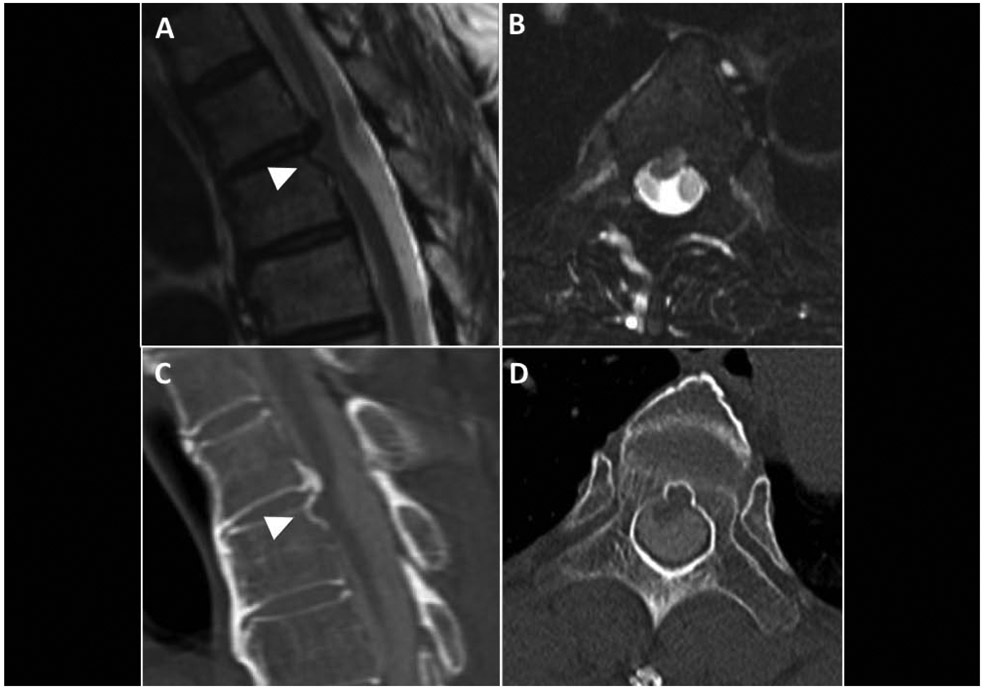

A healthy man in his 60’s presented with a history of decreased sensation in the right lower extremity, worsening left lower extremity weakness, spasticity and gait instability. MRI and CT myelogram findings were consistent with a thoracic spinal cord herniation (SCH, Figure 1). His presentation and exam were concerning for Brown-Sequard syndrome with progressive thoracic myelopathy, and likely due to the ventral thoracic SCH. The patient opted for surgery with the goal of releasing the tethered spinal cord, and repairing the defect.

Figure 1.

Key imaging findings. MRI demonstrated focal displacement of the spinal cord into the T4 vertebral body on (A) sagittal (arrowhead) and (B) axial views. CT myelogram showed obliteration of the ventral CSF space and widening of the dorsal space on (C) sagittal and (D) axial views. Importantly, no filling defect noted dorsally to suggest an underlying arachnoid cyst. The “c-shaped” indentation is a common feature observed with SCH vs. a sharp “scalpel sign” observed with arachnoid webs.9 A calcified disc herniation at T3-4, and scalloping of the posterior margin of the vertebral body at the herniation site was also noted. .Degenerative disc herniation has been postulated in the development of the ventral dural defect.

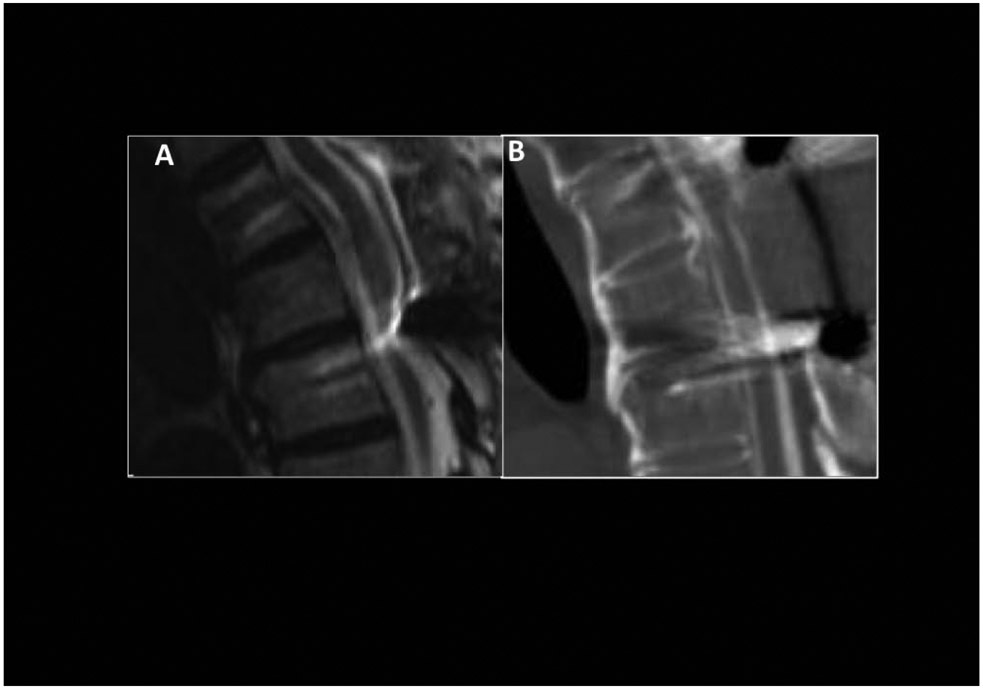

A T3-4 laminectomy, left-sided facetectomy and left-sided T4 pediculectomy was performed to achieve microsurgical access. The protrusion of the spinal cord through the ventral dural defect was adequately visualized for microdissection and repair (Figure 2). Further technique details are highlighted in the Video. Postoperatively, the patient’s sensory and motor symptoms improved, and imaging demonstrated a centrally placed spinal cord (Figure 3). He was discharged to an acute rehabilitative unit with persistent left lower extremity weakness causing gait dysfunction. At 6 months follow-up, his neurological symptoms continued to improve, walking independently with residual distal left lower weakness.

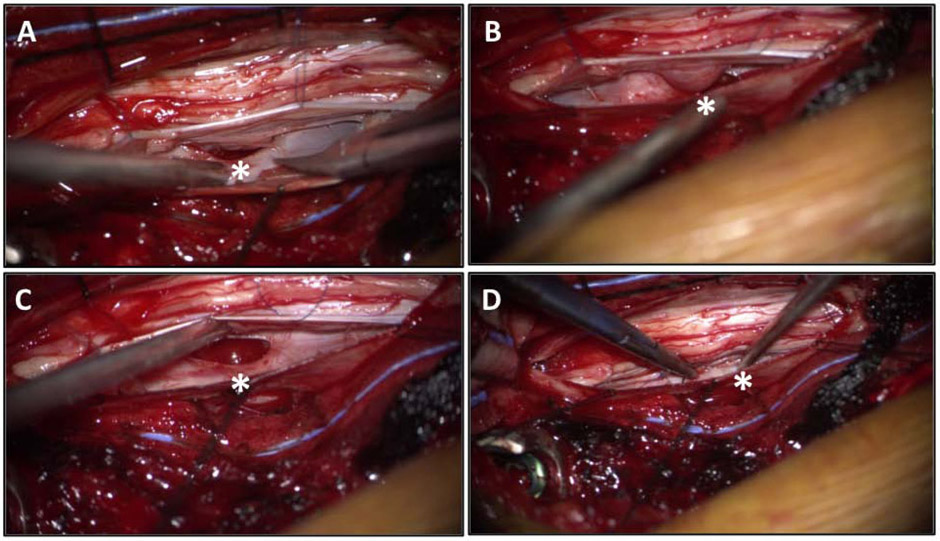

Figure 2.

Intraoperative photo demonstrating the ventral dural defect (asterisk) upon exposure (A), after microdissection and gentle mobilization (B and C) the defect is adequately visualized; and after primary dural repair was performed (D).

Figure 3.

Postoperative MRI (A) and CT myelogram (B) demonstrated detethered spinal cord with restoration of ventral CSF space.

Ventral SCH is a rare condition characterized by displacement of the spinal cord across a defect in the dura.1-4 SCH is most commonly observed in the thoracic spinal cord, likely predisposed due to kyphosis and anterior positioning spinal cord in the thoracic spine. SCH is theorized to be either acquired (i.e. disc-herniation, trauma, iatrogenic) or congenital. Herniation results in a tethered cord from CSF pulsation and pressure gradient (negative in extra-dural space) causing progression of neurological symptoms due to vascular compromise. Erosion into the vertebral body can be observed over time, which can be a poor prognostic indicator (Figure 1).5 Ventral cervical SCH is unusual, most commonly associated with iatrogenic etiologies, and can require more extensive decompression and spinal reconstruction.6

Multiple surgical techniques have been reported for ventral thoracic SCH, with the common goal in detethering the cord and implementing adjunctive steps to reduce the risk for re-herniation.1-4,7 The appropriate surgical corridor should minimize the requirement for cord traction, thereby allowing a safer microdissection while addressing the pathology. The surgical corridor in this case could have been expanded with a modified costotransversectomy and/or bilateral pediculectomy if needed.7 However, a left sided transpedicular approach provided a clear view of the ventral aspect of the thecal sac (Figure 2), which demonstrated the entire dural defect and herniation of the spinal cord tissue. Further bony exposure may not have been needed given that the left-ventral side of the spinal cord was eccentrically herniated with the spinal cord rotated, allowing visualization of the defect.2

Different techniques in addressing the dural defect have been reported.2,4,7 The defect can be closed primarily with sutures or by using a dural patch to minimize manipulation to the cord. Noteworthy, primary repair of the ventral dural defect without adequate visualization carries great risk in injury of the spinal cord.

Widening the dural defect has also been suggested as an effective treatment of the dural defect. This could avoid further manipulation of the cord, but carries a risk for ventral CSF accumulation that may potentially cause clinical symptoms.3 In this case, the transpedicular corridor and spinal cord release (Video) provided adequate visualization of the dural defect without the need for significant mobilization of the spinal cord. The dural defect was freely mobile and adequately visualized which allowed primary repair with minimal retraction. Intraoperative neuromonitoring (IONM) remained stable throughout the case.

The use of IONM for SCH has increased over the recent decade, despite the lack of high-level studies supporting its use.4 The authors recommend implementing IONM, as there have been reports of using IONM with avoiding reversible postoperative motor deficits.8 Surgical reduction of the herniation carries the risk for neurologic deterioration, recurrence, and accumulation of CSF, which may or may not be symptomatic.2-4,8 Despite the risks, neurologic improvements are reported in the majority of cases (up to 75%), .1,2,4 with motor function improvement more commonly observed in patients with Brown-Séquard-like vs. spastic paraparesis deficits.4

Supplementary Material

Highlights in the surgical management of ventral thoracic spinal cord herniation. After performing a routine T3-4 laminectomy, increased lateral exposure was gained with a left sided facetectomy and T4 pediculectomy. The spinal cord herniation was immediately observed after dural opening. The left T4 nerve root and dentate ligaments were transected to allow gentle manipulation of the spinal cord. Microdissection around the spinal cord demonstrated protrusion of the spinal cord through a ventral dural defect. After carefully mobilizing the spinal cord from adhesions through the defect, demineralized bone matrix was placed within the vertebral body defect, the dural defect was repaired with sutures and then a small piece of collagen matrix was positioned around and under the spinal cord. The graft was then sutured to the sides of the thecal sac during closure of the primary dura. This was followed by another collagen matrix onlay and polyethylene glycol hydrogel dural sealant.

Acknowledgments

Funding: J.B and B.A.S are supported by the NIH NINDS Research Education Grant (R25)

Abbreviations:

- MRI

magnetic resonance imaging

- CT

computed tomography

- CSF

cerebrospinal fluid

- SCH

spinal cord herniation

- IONM

intraoperative neuromonitoring

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of interest statement: All authors declare that the article content was composed in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Declaration of interests

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Contributor Information

Joshua Bakhsheshian, Department of Neurological Surgery, Keck School of Medicine, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, California. 1200 N State Street, Suite 3300 Los Angeles, CA 90033..

Ben A. Strickland, Department of Neurological Surgery, Keck School of Medicine, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, California. 1200 N State Street, Suite 3300 Los Angeles, CA 90033..

John C. Liu, Department of Neurological Surgery, Keck School of Medicine, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, California. 1200 N State Street, Suite 3300 Los Angeles, CA 90033..

References

- 1.Randhawa PS, Roark C, Case D, Seinfeld J Idiopathic spinal cord herniation associated with a thoracic disc herniation: case report, surgical video, and literature review. Clin Spine Surg. 2020;33:222–229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Neale N, Ramayya A, Welch W. Surgical Management of Idiopathic Thoracic Spinal Cord Herniation. World Neurosurg. 2019;129:81–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Grobelny BT, Smith M, Perin NI. Failure of Surgery in Idiopathic Spinal Cord Herniation: Case Report and Review of the Literature. World Neurosurg. 2020;133:318–323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Groen RJM, Lukassen JNM, Boer GJ, et al. Anterior Thoracic Spinal Cord Herniation: Surgical Treatment and Postoperative Course. An Individual Participant Data Meta-Analysis of 246 Cases. World Neurosurg. 2019;123:453–463 e415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barbagallo GM, Marshman LA, Hardwidge C, Gullan RW. Thoracic idiopathic spinal cord herniation at the vertebral body level: a subgroup with a poor prognosis? Case reports and review of the literature. J Neurosurg. 2002;97(3 Suppl):369–374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Finneran MM, Schaible K. Ventral Herniation of the Cervical Cord After Single-Level Corpectomy. World Neurosurg. 2020;136:12–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chaichana KL, Sciubba DM, Li KW, Gokaslan ZL. Surgical management of thoracic spinal cord herniation: technical consideration. J Spinal Disord Tech. 2009;22(1):67–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Novak K, Widhalm G, de Camargo AB, et al. The value of intraoperative motor evoked potential monitoring during surgical intervention for thoracic idiopathic spinal cord herniation. J Neurosurg Spine. 2012;16(2):114–126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bhatia K, Madhavan A, Coutinho C, Mathur S Idiopathic spinal cord herniation. Clin Radiol. 2020. doi: 10.1016/j.crad.2020.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Highlights in the surgical management of ventral thoracic spinal cord herniation. After performing a routine T3-4 laminectomy, increased lateral exposure was gained with a left sided facetectomy and T4 pediculectomy. The spinal cord herniation was immediately observed after dural opening. The left T4 nerve root and dentate ligaments were transected to allow gentle manipulation of the spinal cord. Microdissection around the spinal cord demonstrated protrusion of the spinal cord through a ventral dural defect. After carefully mobilizing the spinal cord from adhesions through the defect, demineralized bone matrix was placed within the vertebral body defect, the dural defect was repaired with sutures and then a small piece of collagen matrix was positioned around and under the spinal cord. The graft was then sutured to the sides of the thecal sac during closure of the primary dura. This was followed by another collagen matrix onlay and polyethylene glycol hydrogel dural sealant.