Abstract

Aims/hypothesis

Aggregation of the beta cell secretory product human islet amyloid polypeptide (hIAPP) results in islet amyloid deposition, a pathological feature of type 2 diabetes. Amyloid formation is associated with increased levels of islet IL-1β as well as beta cell dysfunction and death, but the mechanisms that promote amyloid deposition in situ remain unclear. We hypothesised that physiologically relevant concentrations of IL-1β stimulate beta cell islet amyloid polypeptide (IAPP) release and promote amyloid formation.

Methods

We used a humanised mouse model of endogenous beta cell hIAPP expression to examine whether low (pg/ml) concentrations of IL-1β promote islet amyloid formation in vitro. Amyloid-forming islets were cultured for 48 h in the presence or absence of IL-1β with or without an IL-1β neutralising antibody. Islet morphology was assessed by immunohistochemistry and islet mRNA expression, hormone content and release were also quantified. Cell-free thioflavin T assays were used to monitor hIAPP aggregation kinetics in the presence and absence of IL-1β.

Results

Treatment with a low concentration of IL-1β (4 pg/ml) for 48 h increased islet amyloid prevalence (93.52 ± 3.89% vs 43.83 ± 9.67% amyloid-containing islets) and amyloid severity (4.45 ± 0.82% vs 2.16 ± 0.50% amyloid area/islet area) in hIAPP-expressing mouse islets in vitro. This effect of IL-1β was reduced when hIAPP-expressing islets were co-treated with an IL-1β neutralising antibody. Cell-free hIAPP aggregation assays showed no effect of IL-1β on hIAPP aggregation in vitro. Low concentration IL-1β did not increase markers of the unfolded protein response (Atf4, Ddit3) or alter proIAPP processing enzyme gene expression (Pcsk1, Pcsk2, Cpe) in hIAPP-expressing islets. However, release of IAPP and insulin were increased over 48 h in IL-1β-treated vs control islets (IAPP 0.409 ± 0.082 vs 0.165 ± 0.051 pmol/5 islets; insulin 87.5 ± 8.81 vs 48.3 ± 17.3 pmol/5 islets), and this effect was blocked by co-treatment with IL-1β neutralising antibody.

Conclusions/interpretation

Under amyloidogenic conditions, physiologically relevant levels of IL-1β promote islet amyloid formation by increasing beta cell release of IAPP. Neutralisation of this effect of IL-1β may decrease the deleterious effects of islet amyloid formation on beta cell function and survival.

Keywords: hIAPP, IL-1β, Islet amyloid, Type 2 diabetes

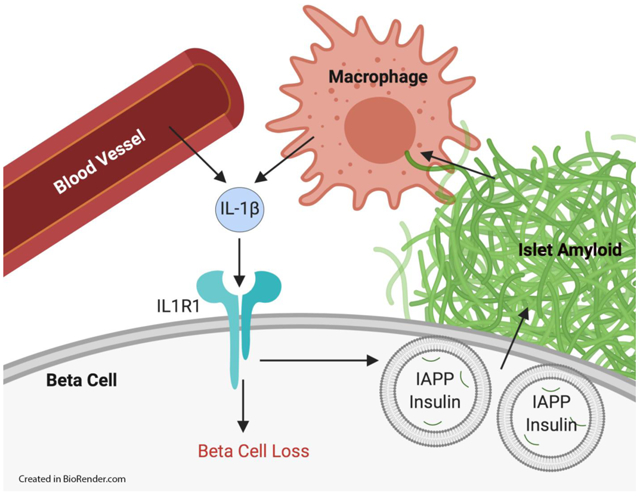

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

Islet amyloid formation occurs in most individuals with type 2 diabetes and is associated with beta cell dysfunction and loss (1-5). Human islet amyloid polypeptide (hIAPP, also known as amylin) is a beta cell secretory product co-released with insulin (6) and the amyloidogenic constituent of islet amyloid deposits (7-9). Because the sequence of hIAPP and mouse islet amyloid polypeptide (mIAPP) differ in a few critical amino acid residues, hIAPP is amyloidogenic and cytotoxic while mIAPP is not (10). Consequently, a number of mouse models with beta cell hIAPP expression have been developed to facilitate the study of islet amyloidosis in type 2 diabetes (11-13). Most of these models use transgenic expression of hIAPP under the rat insulin promoter (RIP), but humanised mice that express hIAPP under the endogenous mIAPP promoter have also been developed to more accurately model hIAPP expression and islet amyloid formation (14,15).

Although the relationship between hIAPP aggregation and beta cell loss is well-established (1,16,17), the mechanisms that promote cytotoxic hIAPP aggregation in situ remain unclear. hIAPP aggregation has previously been shown to activate the NACHT, LRR and PYD domains-containing protein 3 (NLRP3) inflammasome and elicit production of IL-1β from macrophages and dendritic cells, leading to islet inflammation (18-20). This production of IL-1β has been viewed predominantly as a downstream mediator of amyloid’s cytotoxic effect. More recently, IL-1β signalling has been proposed as a promotor of amyloid formation. In human islets, pharmacological concentrations of IL-1β increase amyloid deposition in an IL-1 receptor-dependent manner (21) and neutralisation of endogenous islet IL-1β with an antibody has been shown to mitigate islet amyloid deposition in human islets (22). Similar observations have been made in mouse islets that express hIAPP under the RIP (23). However, the mechanisms linking islet IL-1β signalling and amyloid deposition remain to be fully established.

It is difficult to know the concentration of IL-1β the beta cell is exposed to in vivo but it is believed that IL-1β concentrations in the pg/ml range more accurately replicate the islet microenvironment (24,25) than the ng/ml concentrations that predominate in the literature (21,25,26). Physiologically relevant levels of IL-1β in the pg/ml range have been shown to stimulate insulin secretion (27-30) but the effect on islet amyloid polypeptide (IAPP) release has not been evaluated. Therefore, we hypothesised that pg/ml concentrations of IL-1β directly stimulate release of IAPP from beta cells to further promote cytotoxic hIAPP aggregation under conditions of islet amyloid formation. In this study, we used a humanised mouse model with hIAPP expression driven by the endogenous mIAPP promoter to examine whether physiologically relevant low pg/ml concentrations of IL-1β increase islet amyloid deposition in vitro and, if so, whether increased release of hIAPP from the beta cell may be one mechanism underlying this effect.

Methods

Animals

C57BL/6NHsd mice expressing amyloidogenic hIAPP under the endogenous mIAPP promoter (14) were obtained from N. L. Eberhardt (Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN, USA). Following approval by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee, mice were housed and bred in a specific-pathogen-free vivarium at VA Puget Sound Health Care System with ad libitum access to food and water.

Islet isolation and culture

Islets from 8- to 12-week-old male and female mice were isolated by collagenase digestion, then recovered overnight in RPMI 1640 medium containing 10% FBS, 1 mmol/l sodium pyruvate, 100 U/ml penicillin, 100 μg/ml streptomycin and 11.1 mmol/l glucose. Islets were then distributed into randomised islet pools, and cultured in media containing 16.7 mmol/l glucose and the appropriate experimental condition for 48 h. The following reagents were used during the 48 h culture period for each condition: control, BSA (no. A0281; Sigma, St Louis, USA; 4 pg/ml); IgG, goat IgG isotype control (no. AB-108-C; R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA; 0.4 μg/ml); IL-1β, recombinant mouse IL-1β (no. CYT-273; ProSpec, Rehovot, Israel; concentrations as indicated); NAb, IL-1β neutralising antibody (no. AF-401-NA; R&D Systems; 0.4 μg/ml).

Histology and quantitative microscopy

Islets were fixed in 10% (wt/vol.) neutral buffered formalin, embedded in agar and then paraffin, processed and 10 μm sections were cut. Sections were incubated with mouse monoclonal anti-insulin antibody (no. I2018; Sigma; 1:5000) followed by goat anti-mouse Cy3 (no. 115-165-146; Jackson ImmunoResearch, West Grove, PA, USA; 1:250) to visualise beta cells. To visualise amyloid deposits, sections were stained with Thioflavin S (0.5% vol./vol. in water) for 2 min at room temperature followed by rapid differentiation in 70% ethanol (10 dips), rapid water rinses (10 dips) and a 5 min wash in water to specifically stain amyloid deposits and minimise background. Sections were mounted with polyvinyl alcohol containing Hoechst 33258 to visualise nuclei (31). To visualise dead beta cells, sections were incubated with anti-insulin antibody (no. I2018; Sigma; 1:5000) followed by goat anti-mouse Alexa Fluor 488 (no. A-11001, Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA; 1:1000), then propidium iodide (no. P3566; Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA; 1:250) and RNase A (no. R4642; Sigma; 1:300).

Islet area, beta cell area, amyloid area and propidium iodide-positive nuclei were imaged with a Nikon E800 microscope and 20× Plan Fluor objective (Nikon, Tokyo, Japan) using an X-Cite 120PCQ fluorescence lamp illuminator (Excelitas Technologies, Waltham, MA, USA). For amyloid imaging, an excitation λ of 488 nm was used (excitation 460–500 nm bandpass filter cube; emission 505 dichromatic mirror and 510–560 nm bandpass barrier filter). Images were quantified using computer-based quantitative imaging software (NIS Elements AR 4.30.02, Nikon, Tokyo, Japan) with the observer blinded to culture condition of the islets. A mean of 26.5±1.1 islets per replicate per condition were analysed.

Preparation and purification of hIAPP

hIAPP was synthesised using 9-fluorenylmethyloxycarbonyl (Fmoc) chemistry with a CEM Liberty Blue microwave peptide synthesizer (CEM Corp, Matthews, NC, USA) on a 0.10 mmol scale. 5-(4′-Fmoc-aminomethyl-3’,5-dimethoxyphenol) valeric acid (PAL-PEG) resin was used to provide an amidated C terminus. hIAPP produced in vivo is amidated at the C terminus and the chemical nature of the C terminus, amide vs carboxyl, has been shown to impact hIAPP aggregation kinetics and induction of physiological responses (32,33). Pseudoproline derivatives were used at residue 9 and 10 (Ala and Thr), residue 19 and 20 (Ser and Ser), and residue 27 and 28 (Leu and Ser) to minimise aggregation during synthesis (34,35). The peptide was released from the resin and the side chain protecting groups were removed using a trifluoroacetic acid (TFA)-based cleavage cocktail (92.5% TFA, 2.5% triisopropylsilane, 2.5% 3,6-dioxa-1,8-octanedithiol and 2.5% water). Crude product was dissolved in 20% acetic acid (4 mg/ml) frozen in liquid nitrogen and lyophilised to increase their solubility. The disulfide bond was formed by DMSO oxidation (10 mg/ml peptide in 100% DMSO) at room temperature for 4 days. hIAPP was purified using reverse-phase HPLC with a C18 25mm × 250mm column (Higgins Analytical, Mountain View, CA, USA). A binary gradient of buffer A (100% H2O and 0.045% HCl) and buffer B (80% acetonitrile, 20% H2O and 0.045% HCl) was employed. HCl was used as the counter ion since TFA may affect Thioflavin T kinetic assays and cell toxicity experiments. The product from the HPLC purification was dissolved in 100% hexafluoroisopropanol (10 mg/ml) for 4 h and subjected to a second round of HPLC purification to remove any residual scavengers. Direct injection electrospray MS confirmed the mass of the pure peptide: expected 3903.32, observed 3903.03. Analytical reverse-phase HPLC (C18) was used to confirm the purity of the samples. Peptides were greater than 96% pure. Quality control experiments confirmed that the purified synthetic hIAPP formed amyloid fibres with typical morphology after aggregation in vitro as assessed by transmission electron microscopy (electronic supplementary material [ESM] Fig. 1).

Thioflavin T assays

Kinetics of hIAPP aggregation were determined using solutions containing 20 μmol/l synthetic hIAPP, 32 μmol/l Thioflavin T (no. T3516; Sigma) and 20 mmol/l Tris-HCl (pH 7.4) in the presence or absence of 4 pg/ml IL-1β (no. CYT-273; ProSpec) at 37°C with plate shaking every 10 min and measurements taken every 60 min for 48 h. Thioflavin T is a small molecule, the quantum yield of which increases upon binding to amyloid fibres. The dye offers a simple probe of amyloid formation and has been widely used in studies of amyloid formation by hIAPP (36,37). The concentration of Thioflavin T used has been shown not to alter the kinetics of hIAPP amyloid formation (36). Control reactions were carried out in the absence of hIAPP. Fluorescence measurements were recorded on a Beckman Coulter DTX880 plate reader (Beckman Coulter, Brea, CA, USA) using an excitation λ of 450 nm and emission λ of 485 nm. The assay was performed in triplicate in four independent experiments.

Quantitative real-time RT-PCR

Total RNA was recovered from islets using the High Pure RNA Isolation Kit (Roche, Basel, Switzerland), then reverse transcribed and subjected to quantitative RT-PCR. Data were normalised to 18S rRNA levels and expressed as fold relative to control using the 2−ΔΔCt method. All quantitative RT-PCR data represent means of triplicate determinations. Taqman probes (ThermoFisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) were used to quantify relative expression of the following mRNA targets: Atf4 (Mm00515324); Cpe (Mm00516341_m1); Ddit3/Chop (Mm00492097_m1); Iapp (Mm00439403_m1); Il1b (Mm00434228_m1); Ins2 (Mm00731595_gH); Nos2 (Mm00440502_m1); Pcsk1 (Mm00479023_m1); Pcsk2 (Mm00500981_m1); and 18S (HS99999901_s1).

Insulin and IAPP assays

After a culture period of 48 h in the indicated condition, islet media were collected and islet content extracted with acid–ethanol. IAPP was measured in media and cell extracts with an IAPP ELISA against total (amidated and deamidated) hIAPP with a capture antibody that recognises an epitope near the midpoint of monomeric hIAPP (no. EZHAT-51K; Millipore, Burlington, MA, USA). Insulin was measured with an insulin ELISA (no. 80-INSMSU-E10; ALPCO, Salem, NH, USA) (15). ELISA experimenters were blinded to the culture condition of islet samples. Each measure represents the mean of triplicate determinations of five islets.

Statistical analyses

Amyloid prevalence was defined as the percentage of all islets analysed in each condition that contained amyloid. Amyloid severity was defined as (Σ amyloid area/Σ islet area) × 100% for all islets from each condition, beta cell area was calculated as (Σ beta cell area/Σ islet area) × 100% for all islets from each condition, and beta cell death was calculated as (Σ dead beta cells/Σ total cells) × 100% for all islets from each condition (1,17,38). Normality of data distribution in each dataset was tested using the D’Agostino–Pearson normality test. Paired statistics were applied when all replicates contained all experimental conditions and islets were isolated, cultured and analysed at the same time within a replicate. For data sets with two groups, normally distributed data were analysed using paired two-tailed Student’s t test, while non-normally distributed data were analysed using the Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed rank test. Data sets with more than two groups were all found to be normally distributed, with ordinary one-way ANOVA used for unpaired data and repeated measures one-way ANOVA used for paired data. ANOVA tests were followed by Fisher’s least significant difference (LSD) post hoc tests to compare specific groups. Statistical analyses were conducted with GraphPad Prism 8 software (GraphPad, San Diego, CA, USA). Data are presented as mean ± SEM and a value of p<0.05 was considered significant.

Results

Low concentration IL-1β increases islet amyloid prevalence and severity in vitro

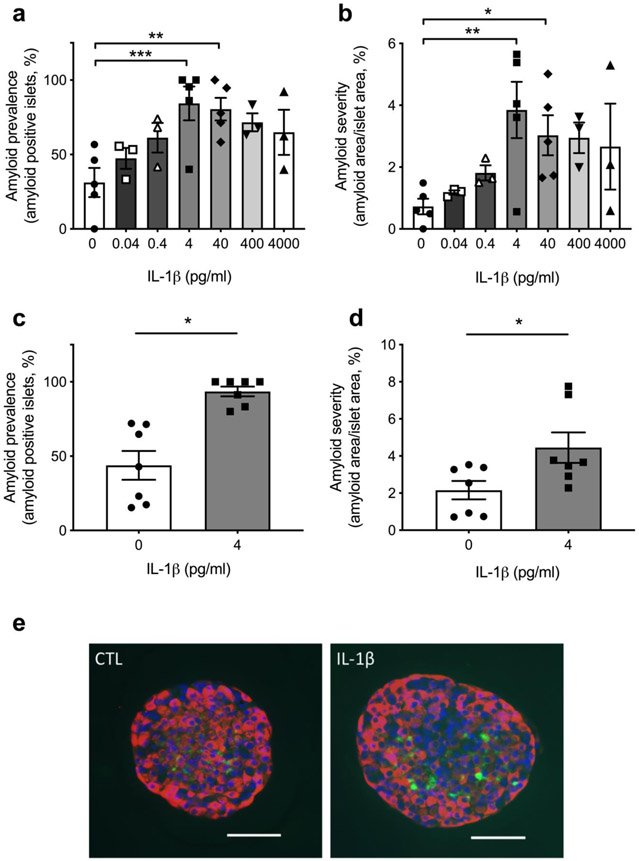

hIAPP-expressing islets were treated with recombinant mouse IL-1β in concentrations ranging from 0 to 4000 pg/ml to examine the dose–response effect on islet amyloid deposition. These concentrations of IL-1β were found to increase islet amyloid deposition, with concentrations as low as 4 pg/ml significantly increasing amyloid prevalence (Fig. 1a) and severity (Fig. 1b). A separate observer confirmed these findings in an independent series of experiments using only the 4 pg/ml concentration of IL-1β, with this low concentration again significantly increasing islet amyloid prevalence (93.52 ± 3.89% vs 43.83 ± 9.67% amyloid-containing islets, n=7, p<0.05) (Fig. 1c) and severity (4.45 ± 0.82% vs 2.16 ± 0.50% amyloid area/islet area, n=7, p<0.05) (Fig. 1d). Representative images of control (vehicle-treated) and IL-1β-treated hIAPP-expressing islets illustrate the amyloid deposition observed (Fig. 1e).

Fig. 1.

Low concentration IL-1β increases islet amyloid prevalence and severity in vitro. (a, b) Treatment of hIAPP-expressing mouse islets with IL-1β (0–4000 pg/ml) dose-dependently increases islet amyloid prevalence (% of islets containing amyloid) (a) and amyloid severity (% of amyloid-positive islet area) (b). (c, d) Induction of amyloid prevalence (c) and amyloid severity (d) were verified in separate experiments using only vehicle (black circles) and 4 pg/ml IL-1β (black squares). (e) Representative images of vehicle- and 4 pg/ml IL-1β-treated hIAPP-expressing mouse islets (insulin, red; amyloid, green; DNA, blue). Data are presented as mean ± SEM. n=3–7. *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001. CTL, control (vehicle)

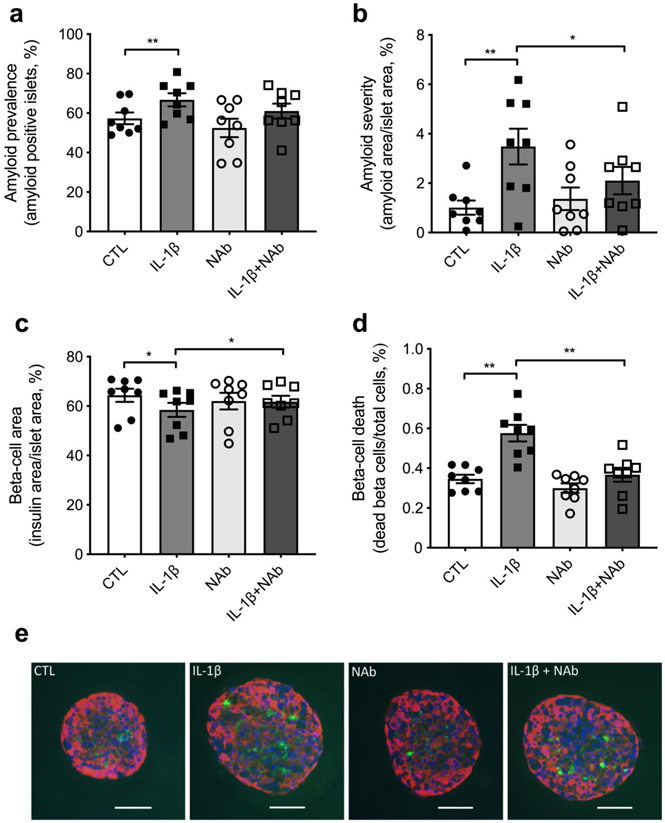

Neutralisation of IL-1β prevents low concentration IL-1β-mediated islet amyloid deposition and beta cell loss

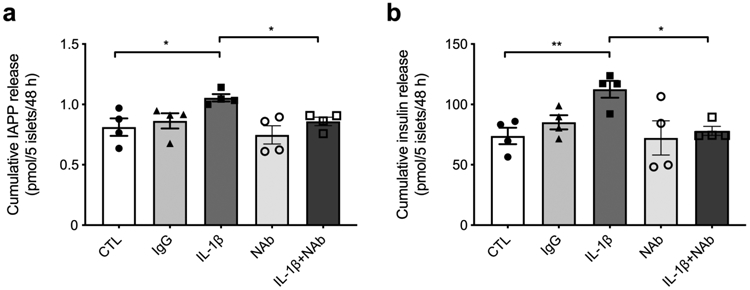

To test the specificity of the effect of low concentration (4 pg/ml) IL-1β treatment, studies using an IL-1β neutralising antibody were undertaken. Low concentration IL-1β again increased amyloid deposition (Fig. 2a, b), resulting in a significant reduction in beta cell area (58.47 ± 2.85% vs 64.37 ± 2.67% insulin area/islet area, n=8, p<0.05) (Fig. 2c) and a significant increase in beta cell death (0.567 ± 0.042% vs 0.346 ± 0.021% dead beta cells/total cells, n=8, p<0.01) (Fig. 2d) compared with vehicle treatment. When IL-1β was neutralised with an excess of IL-1β antibody (0.4 μg/ml), amyloid severity (Fig. 2b) and beta cell death (Fig. 2d) were decreased, and beta cell area (Fig. 2c) was increased compared with IL-1β treatment alone. A non-significant (p=0.08) reduction in amyloid prevalence was also observed when IL-1β was neutralised, compared with IL-1β alone (Fig. 2a). On its own, the neutralising antibody showed no significant effect on these measures (Fig. 2a-d). Representative images illustrate the amyloid deposition and beta cell area observed under these conditions (Fig. 2e).

Fig. 2.

Neutralisation of IL-1β prevents low concentration IL-1β-mediated islet amyloid deposition and beta cell loss. (a–d) hIAPP-expressing mouse islets treated with low concentration IL-1β (4 pg/ml, black squares) exhibited increased amyloid prevalence (a) and severity (b), reduced beta cell area (c) and increased beta cell death (d) when compared with islets treated with vehicle (black circles). IL-1β-mediated changes in amyloid severity, beta cell area and beta cell death were blocked by co-treatment with an IL-1β neutralising antibody (0.4 μg/ml, white squares). (e) Representative images of hIAPP-expressing mouse islets treated in the presence or absence of low concentration IL-1β and IL-1β neutralising antibody (insulin, red; amyloid, green; DNA, blue). Data are presented as mean ± SEM. n=8. *p<0.05, **p<0.01. CTL, control (vehicle); NAb, IL-1β neutralising antibody

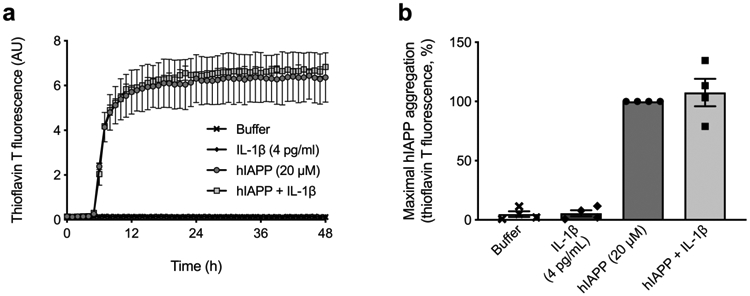

hIAPP aggregation kinetics are not increased by low concentration IL-1β in a cell-free system

To determine whether the increased amyloid deposition observed with low concentration IL-1β was due to an effect of the cytokine to directly interact with hIAPP, cell-free Thioflavin T assays were performed to monitor hIAPP aggregation kinetics. The presence of IL-1β did not change the rate of hIAPP aggregation or maximal signal in the Thioflavin T fibril formation assays (Fig. 3a, b) over 48 h. Further, no aggregation was observed with IL-1β or buffer in the absence of hIAPP (Fig. 3a, b). These findings suggest that IL-1β’s effect of increasing islet amyloid deposition is mediated by IL-1β signal transduction in islet cells.

Fig. 3.

Low concentration IL-1β does not increase hIAPP aggregation kinetics. (a) Aggregation of hIAPP was carried out in the absence (circles) or presence (squares) of 4 pg/ml IL-1β and monitored for 48 h by Thioflavin T fluorescence in a cell-free system. One representative experiment is shown with technical replicates. (b) Quantification of maximal hIAPP aggregation revealed no differences in hIAPP aggregation without (black circles) or with (black squares) 4 pg/ml IL-1β. In the absence of hIAPP, neither buffer nor IL-1β increased Thioflavin T signal. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. n=4. AU, arbitrary units

Low concentration IL-1β increases IAPP release in vitro and this effect is blocked by neutralisation of IL-1β

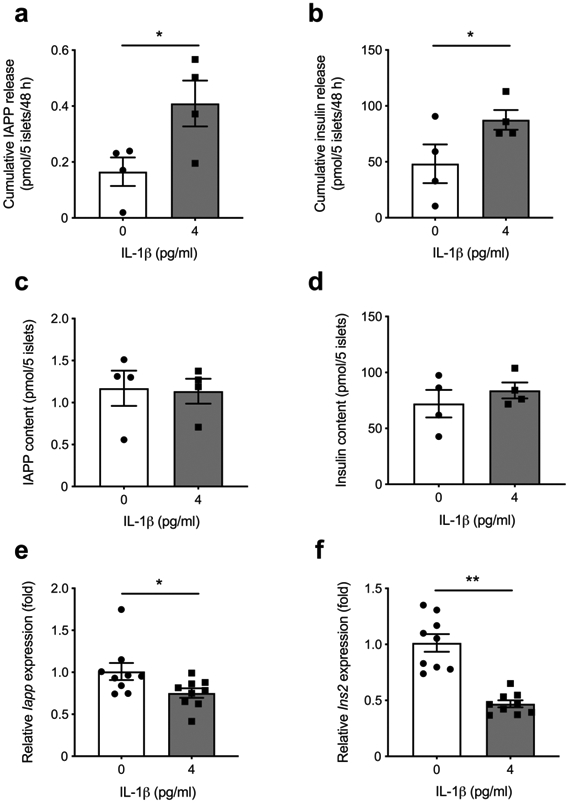

To examine whether increased IAPP release plays a role in IL-1β-mediated amyloid deposition in our model, we quantified cumulative release of IAPP from islets cultured for 48 h in the presence or absence of low concentration IL-1β. IL-1β at 4 pg/ml significantly increased IAPP (0.409 ± 0.082 vs 0.165 ± 0.051 pmol/5 islets, n=4, p<0.05) (Fig. 4a) and insulin (87.5 ± 8.81 vs 48.3 ± 17.3 pmol/5 islets, n=4, p<0.05) (Fig. 4b) release from islets over 48 h in culture, but did not alter the IAPP/insulin secretion ratio (data not shown). At the end of this culture period, neither IAPP (1.14 ± 0.148 vs 1.17 ± 0.210 pmol/5 islets, n=4) (Fig. 4c) nor insulin (84.0 ± 7.11 vs 72.1 ± 12.3 pmol/5 islets) (Fig. 4d) protein content was altered in IL-1β-treated islets. Iapp (Fig. 4e) and Ins2 (Fig. 4f) mRNA expression were significantly reduced by low concentration IL-1β following 48 h culture. Notably, IL-1β neutralisation prevented the increase in release of IAPP (Fig. 5a) and insulin (Fig. 5b) observed with low concentration IL-1β treatment.

Fig. 4.

Low concentration IL-1β increases IAPP release in vitro. (a–d) Treatment of hIAPP-expressing mouse islets with 4 pg/ml IL-1β (black squares) increased release of IAPP (a) and insulin (b) into the media over 48 h in culture when compared with vehicle treatment (black circles). At the end of the 48 h culture period, the islet content of IAPP (c) and insulin (d) protein did not differ between groups. (e, f) Iapp (e) and Ins2 (f) mRNA expression were decreased in IL-1β-treated (black squares) compared with vehicle-treated (black circles) islets (data normalised to 18S rRNA levels and expressed as fold relative to control using the 2−ΔΔCt method). Data are presented as mean ± SEM. n=4–9. *p<0.05, **p<0.01

Fig. 5.

Neutralisation of IL-1β blocks low concentration IL-1β-mediated IAPP release. Following 48 h treatment, release of IAPP (a) and insulin (b) from hIAPP-expressing islets were significantly increased by 4 pg/ml IL-1β (black squares) compared with vehicle (black circles). The release of IAPP (a) and insulin (b) mediated by low concentration IL-1β (black squares) was reduced when islets were co-treated with 0.4 μg/ml of IL-1β neutralising antibody (white squares). Data are presented as mean ± SEM. n=4. *p<0.05, **p<0.01. CTL, control (vehicle); NAb, IL-1β neutralising antibody

Low concentration IL-1β does not alter the unfolded protein response or processing enzyme gene expression in hIAPP-expressing islets

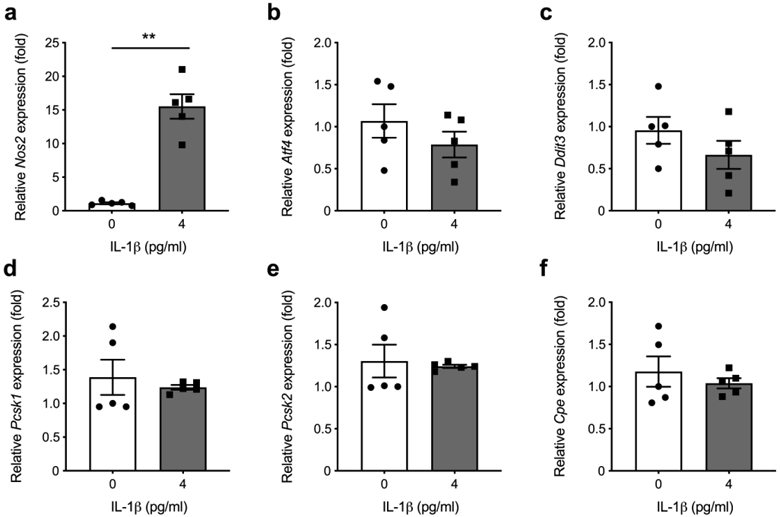

Expression of genes in the pathways involved in the unfolded protein response (UPR) and proIAPP processing were examined to determine whether they may contribute to the observed effect of IL-1β on amyloid deposition in our model. Since increased Nos2 gene expression is a marker of beta cell IL-1β signalling at pharmacological concentrations (39), we first confirmed that Nos2 expression was increased in the presence of 4 pg/ml IL-1β. We found Nos2 gene expression was increased more than 15-fold compared with when no IL-1β was present (Fig. 6a), indicating that IL-1β stimulates known cell signalling events at this concentration. To evaluate whether low concentration IL-1β alters the UPR or proIAPP processing, we next examined gene expression of Atf4 and Ddit3 as markers of the UPR, along with Pcsk1, Pcsk2 and Cpe as indicators of proIAPP processing. In contrast to Nos2, low concentration IL-1β had no effect on islet expression of Atf4 (Fig. 6b) or Ddit3 (Fig. 6c). Further, it did not alter gene expression of the proIAPP processing enzymes Pcsk1 (Fig. 6d), Pcsk2 (Fig. 6e) or Cpe (Fig. 6f).

Fig. 6.

Low concentration IL-1β does not alter the UPR or processing enzyme gene expression in hIAPP-expressing islets. (a–c) Treatment of hIAPP-expressing mouse islets with low concentration IL-1β for 48 h (black squares) significantly increased Nos2 mRNA expression, compared with vehicle treatment (black circles) (a), but mRNA expression of Atf4 (b) or Ddit3 (c), markers of the UPR, remained unaltered. (d–f) Similarly, mRNA expression of the proIAPP processing enzymes Pcsk1 (d), Pcsk2 (e) and Cpe (f) was unchanged in hIAPP-expressing islets following vehicle treatment (black circles) vs treatment with 4 pg/ml IL-1β (black squares). Data are normalised to 18S rRNA levels and expressed as fold relative to control using the 2−ΔΔCt method. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. n=5. **p<0.01

Discussion

Study of the relationship between islet amyloid formation and IL-1β signalling has focused primarily on the role of hIAPP in inducing IL-1β production from islet macrophages, thus promoting islet inflammation and beta cell loss (18,19). However, recent studies provide evidence that not only does hIAPP aggregation lead to IL-1β production but, conversely, that islet IL-1β signalling promotes amyloid formation (21-23). These findings suggest that a feed-forward system of islet inflammation related to IL-1β signalling, hIAPP aggregation and beta cell cytotoxicity exists.

In this study we used an isolated islet model of endogenous beta cell hIAPP expression and pg/ml concentrations of IL-1β to demonstrate, for the first time, that low concentration IL-1β stimulates IAPP release from islet beta cells, and that under conditions associated with amyloid formation in vitro, this increased release of IAPP leads to increased islet amyloid deposition. Although previous studies demonstrated that low concentrations of IL-1β can stimulate insulin secretion (27-30,40), its effect on IAPP release has not been reported or linked to IL-1β-mediated islet amyloid formation and beta cell loss. It is known that circulating IL-1β promotes insulin resistance, which in turn stimulates insulin secretion to maintain euglycaemia in vivo (41,42). However, less is known about the mechanisms underlying the direct effect of low concentration IL-1β on IAPP and insulin release from islets in vitro (27-29).

Given our in vitro approach using isolated islets and the experimental conditions tested, we believe we have negated any differences that may be imposed on the beta cell secretory response by the varying glucose concentrations or differences in insulin sensitivity that can occur in vivo. Therefore, our findings suggest that in vivo, physiologically relevant concentrations of IL-1β derived from the circulation and/or islet immune cells can directly induce IAPP release from the beta cell and promote cytotoxic islet amyloid formation in the setting of type 2 diabetes. Importantly, we believe that this IL-1β-mediated increase in IAPP release is not likely to be the factor responsible for initiating amyloid formation, but rather for exacerbating it. This hypothesis is supported by the observations that IAPP is a normal beta cell secretory product co-released with insulin (6) and that islet amyloid typically is not observed in healthy humans (1) who exhibit higher IAPP release than those with type 2 diabetes (43). Additional studies are therefore needed to understand the factors that initiate islet amyloid formation and allow IL-1β to exacerbate beta cell loss in the pathophysiology of type 2 diabetes.

We identified increased release of IAPP by the beta cell, and thus increased substrate for amyloid formation, as a major mechanism underlying the effect of low concentration IL-1β on islet amyloid deposition. This finding is consistent with previous studies that observed a positive relationship between beta cell IAPP release and islet amyloid deposition (44,45). Although concentrations of cytokines higher than those used here have been shown to induce the UPR (26,46), we found that low concentration IL-1β treatment did not increase expression of the UPR markers Atf4 or Ddit3 in hIAPP-expressing islets, indicating that the observed increase in amyloid deposition was not associated with endoplasmic reticulum stress. Additionally, we found that low concentration IL-1β did not change gene expression of the proIAPP processing enzymes Pcsk1, Psck2 or Cpe. Although IL-1β has been shown to impair IAPP processing in the setting of islet amyloid formation in other models (21), our data suggest that low concentration IL-1β may not have this effect in mouse islets expressing hIAPP under the endogenous promoter. Furthermore, our quantification of hIAPP aggregation kinetics in a cell-free system shows that IL-1β does not directly increase hIAPP aggregation via physical interaction. Together, these data indicate that low concentration IL-1β signalling leads to increased beta cell IAPP release and that this increase in substrate underlies IL-1β’s effect of increasing islet amyloid formation under pathophysiological conditions.

To evaluate the role of IL-1β signalling in promoting islet amyloid formation in situ, it is important to know the concentration of IL-1β that beta cells are exposed to under normal and pathophysiological conditions (25). In the setting of metabolic disease, the level of IL-1β present in islets is thought to depend primarily on levels of circulating IL-1β originating from immune cells in inflamed adipose tissue (24,47,48) and also on intra-islet production of IL-1β from islet immune cells such as macrophages (18-20). Circulating concentrations of IL-1β in control mice are estimated to be 10 pg/ml, with an increase to ~35 pg/ml observed in obese db/db mice (24). In humans, circulating IL-1β concentrations are thought to range from 0.5 to 12 pg/ml (24,48), although some reports suggest they are higher (47). Estimating the concentration of IL-1β inside the islet is difficult. However, it is believed that cytokine production by islet immune cells, such as in hIAPP-induced IL-1β production by macrophages, results in a further elevation of intra-islet cytokine concentrations and an increase in islet cytokine signalling (18,19,25). Thus, we believe the concentration of IL-1β used here approximates those found in the islet microenvironment in vivo. As such, this study replicates the role of islet IL-1β signalling in promoting IAPP release and amyloid deposition in situ, and we believe it is more informative for understanding islet pathophysiology than studies using high concentrations of IL-1β.

Our findings suggest that islet IL-1β signalling and amyloid formation participate in a feed-forward system of islet inflammation and beta cell loss in the pathogenesis of type 2 diabetes. We propose a model wherein beta cell IL-1β signalling increases hIAPP release and amyloid formation, as shown in the present study. In response to hIAPP aggregation, islet macrophages increase NLRP3-dependent IL-1β production (18), further enhancing IL-1β signalling in the beta cell, hIAPP release, cytotoxic amyloid formation and beta cell loss (1,3). Over time, such a system of amyloid formation and islet inflammation may be an important contributor to the beta cell dysfunction and loss observed in type 2 diabetes. It should be noted, in contrast to our model, that depletion of macrophages in vivo has been shown to increase islet amyloid deposition (19), an observation consistent with earlier findings that islet amyloid fibrils can be phagocytosed by macrophages (49). Thus, macrophages likely play a dual role, removing amyloid fibrils to maintain islet homeostasis under physiological conditions, and increasing IL-1β production and hIAPP aggregation in pathophysiological settings related to type 2 diabetes.

In summary, we have demonstrated that a concentration of IL-1β approximating the concentration found in the islet in vivo increases islet amyloid formation and decreases beta cell area. This effect is likely mediated through increased release of hIAPP from the beta cell, thereby providing additional substrate for cytotoxic amyloid formation. We posit that this effect of low concentration IL-1β to stimulate islet amyloid formation leads to a feed-forward system of IL-1β production, hIAPP aggregation and beta cell toxicity. Early efforts to block this effect of IL-1β may protect the islet from inflammation and hIAPP-induced beta cell cytotoxicity in the setting of type 2 diabetes.

Supplementary Material

Research in context.

What is already known about this subject?

Islet amyloid is present in most individuals with type 2 diabetes, in whom it is associated with increased beta cell death and reduced beta cell area

IL-1β is produced by islet macrophages and dendritic cells in response to human islet amyloid polypeptide (hIAPP), a normal beta cell secretory product

Physiologically relevant (pg/ml) concentrations of IL-1β can increase insulin release from beta cells

What is the key guestion?

Does low concentration IL-1β increase endogenous islet amyloid formation by increasing hIAPP release from beta cells?

What are the new findings?

Low (pg/ml) concentrations of IL-1β increase endogenous islet amyloid formation and decrease beta cell area in isolated humanised mouse islets

Beta cell release of islet amyloid polypeptide (IAPP) increases when treated with low concentration IL-1β, thereby augmenting islet amyloid deposition

IL-1β-mediated IAPP release and amyloid formation are blocked by IL-1β neutralization

How might this impact on clinical practice in the foreseeable future?

Efforts to block islet IL-1β signalling may protect the islet from amyloid formation and beta cell cytotoxicity in the setting of type 2 diabetes

Acknowledgements

We thank E. Boyko (University of Washington, Seattle, WA, USA) and S. Edelstein (George Washington University, Washington, DC, USA) for consultation related to statistical analyses. We thank B. Barrow, B. Fountaine, D. Hackney, S. Mongovin and C. Schmidt (Seattle Institute for Biomedical and Clinical Research, Seattle, WA, USA) for the excellent technical assistance provided during the performance of these studies. We thank N. Eberhardt, (Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN, USA) for providing mice with endogenous hIAPP expression for use in this study. Some of the data from this study were presented at the ADA 77th and 79th Scientific Sessions in 2017 and 2019. The graphical abstract was created with BioRender.com.

Funding

This work was supported by funding from the Department of Veterans Affairs (IK2BX004659 to ATT, I01BX004063 to RLH, I01BX001060 to SEK), National Institutes of Health (P30DK017047 to the University of Washington Diabetes Research Center, T32DK007247 and T32HL007028 to the University of Washington, F32DK109584 to MFH, R01DK098506 to SZ, R01GM078114 to DPR), American Diabetes Association (Mentor-Based Fellowship to SEK, Postdoctoral Fellowship 1-18-PDF-174 to MFH), the University of Washington (McAbee Fellowship to DTM, MFH and NE), the French Society of Diabetes (to NE) and the Swiss National Science Foundation (to DTM).

Abbreviations

- Fmoc

9-Fluorenylmethyloxycarbonyl

- hIAPP

Human islet amyloid polypeptide

- IAPP

Islet amyloid polypeptide

- mIAPP

Mouse islet amyloid polypeptide

- NLRP3

NACHT, LRR and PYD domains-containing protein 3

- RIP

Rat insulin promoter

- TFA

Trifluoroacetic acid

- UPR

Unfolded protein response

Footnotes

Data availability

Data supporting the conclusions of this work are included within the article and are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Duality of interest

The authors declare that there are no relationships or activities that might bias, or be perceived to bias, this work.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This Author Accepted Manuscript is a PDF file of a an unedited peer-reviewed manuscript that has been accepted for publication but has not been copyedited or corrected. The official version of record that is published in the journal is kept up to date and so may therefore differ from this version.

References

- 1.Jurgens CA, Toukatly MN, Fligner CL, et al. β-Cell loss and β-cell apoptosis in human type 2 diabetes are related to islet amyloid deposition. Am J Pathol. 2011. June;178(6):2632–2640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhao H-L, Lai FMM, Tong PCY, et al. Prevalence and clinicopathological characteristics of islet amyloid in Chinese patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes. 2003. November;52(11):2759–2766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Westermark P Quantitative studies on amyloid in the islets of Langerhans. Ups J Med Sci. 1972;77(2):91–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Butler AE, Janson J, Bonner-Weir S, Ritzel R, Rizza RA, Butler PC. β-Cell deficit and increased beta-cell apoptosis in humans with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes. 2003. January;52(1):102–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.MacArthur DL, de Koning EJ, Verbeek JS, Morris JF, Clark A. Amyloid fibril formation is progressive and correlates with beta-cell secretion in transgenic mouse isolated islets. Diabetologia. 1999. October;42(10):1219–1227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kahn SE, D’Alessio DA, Schwartz MW, et al. Evidence of cosecretion of islet amyloid polypeptide and insulin by β-cells. Diabetes. 1990. May;39(5):634–638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Westermark P, Wernstedt C, Wilander E, Hayden DW, O’Brien TD, Johnson KH. Amyloid fibrils in human insulinoma and islets of Langerhans of the diabetic cat are derived from a neuropeptide-like protein also present in normal islet cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1987. June;84(11):3881–3885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Westermark P, Wilander E, Westermark GT, Johnson KH. Islet amyloid polypeptide-like immunoreactivity in the islet B cells of type 2 (non-insulin-dependent) diabetic and non-diabetic individuals. Diabetologia. 1987. November 1;30(11):887–892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cooper GJ, Willis AC, Clark A, Turner RC, Sim RB, Reid KB. Purification and characterization of a peptide from amyloid-rich pancreases of type 2 diabetic patients. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1987. December;84(23):8628–8632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Westermark P, Engström U, Johnson KH, Westermark GT, Betsholtz C. Islet amyloid polypeptide: pinpointing amino acid residues linked to amyloid fibril formation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1990. July;87(13):5036–5040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.D’Alessio DA, Verchere CB, Kahn SE, et al. Pancreatic expression and secretion of human islet amyloid polypeptide in a transgenic mouse. Diabetes. 1994. December;43(12):1457–1461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Butler AE, Jang J, Gurlo T, Carty MD, Soeller WC, Butler PC. Diabetes due to a progressive defect in β-cell mass in rats transgenic for human islet amyloid polypeptide (HIP rat): a new model for type 2 diabetes. Diabetes. 2004. June;53(6):1509–1516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Soeller WC, Janson J, Hart SE, et al. Islet amyloid-associated diabetes in obese A(vy)/a mice expressing human islet amyloid polypeptide. Diabetes. 1998. May;47(5):743–750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hiddinga HJ, Sakagashira S, Ishigame M, et al. Expression of wild-type and mutant S20G hIAPP in physiologic knock-in mouse models fails to induce islet amyloid formation, but induces mild glucose intolerance. J Diabetes Investig. 2012. March 28;3(2):138–147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Meier DT, Entrup L, Templin AT, et al. The S20G substitution in hIAPP is more amyloidogenic and cytotoxic than wild-type hIAPP in mouse islets. Diabetologia. 2016;59(10):2166–2171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kahn SE, Andrikopoulos S, Verchere CB. Islet amyloid: a long-recognized but underappreciated pathological feature of type 2 diabetes. Diabetes. 1999. February;48(2):241–253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hull RL, Andrikopoulos S, Verchere CB, et al. Increased dietary fat promotes islet amyloid formation and β-cell secretory dysfunction in a transgenic mouse model of islet amyloid. Diabetes. 2003. February;52(2):372–379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Masters SL, Dunne A, Subramanian SL, et al. Activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome by islet amyloid polypeptide provides a mechanism for enhanced IL-1β in type 2 diabetes. Nat Immunol. 2010. October;11(10):897–904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Westwell-Roper CY, Ehses JA, Verchere CB. Resident macrophages mediate islet amyloid polypeptide-induced islet IL-1β production and β-cell dysfunction. Diabetes. 2014. May;63(5):1698–1711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Meier DT, Morcos M, Samarasekera T, Zraika S, Hull RL, Kahn SE. Islet amyloid formation is an important determinant for inducing islet inflammation in high-fat-fed human IAPP transgenic mice. Diabetologia. 2014. September;57(9):1884–1888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Park YJ, Warnock GL, Ao Z, et al. Dual role of interleukin-1β in islet amyloid formation and its β-cell toxicity: Implications for type 2 diabetes and islet transplantation. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2017;19(5):682–694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hui Q, Asadi A, Park YJ, et al. Amyloid formation disrupts the balance between interleukin-1β and interleukin-1 receptor antagonist in human islets. Mol Metab. 2017;6(8):833–844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Westwell-Roper CY, Chehroudi CA, Denroche HC, Courtade JA, Ehses JA, Verchere CB. IL-1 mediates amyloid-associated islet dysfunction and inflammation in human islet amyloid polypeptide transgenic mice. Diabetologia. 2015. March;58(3):575–585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.O’Neill CM, Lu C, Corbin KL, et al. Circulating levels of IL-1B+IL-6 cause ER stress and dysfunction in islets from prediabetic male mice. Endocrinology. 2013. September;154(9):3077–3088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nunemaker CS. Considerations for defining cytokine dose, duration, and milieu that are appropriate for modeling chronic low-grade inflammation in type 2 diabetes. J Diabetes Res. 2016;2016:2846570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Templin AT, Maier B, Tersey SA, Hatanaka M, Mirmira RG. Maintenance of Pdx1 mRNA translation in islet β-cells during the unfolded protein response. Mol Endocrinol. 2014. November;28(11):1820–1830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Palmer JP, Helqvist S, Spinas GA, et al. Interaction of β-cell activity and IL-1 concentration and exposure time in isolated rat islets of Langerhans. Diabetes. 1989. October;38(10):1211–1216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jeong I-K, Oh S-H, Chung J-H, et al. The stimulatory effect of IL-1β on the insulin secretion of rat pancreatic islet is not related with iNOS pathway. Exp Mol Med. 2002. March 31;34(1):12–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Arous C, Ferreira PG, Dermitzakis ET, Halban PA. Short term exposure of beta cells to low concentrations of interleukin-1β improves insulin secretion through focal adhesion and actin remodeling and regulation of gene expression. J Biol Chem. 2015. March 6;290(10):6653–6669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hajmrle C, Smith N, Spigelman AF, et al. Interleukin-1 signaling contributes to acute islet compensation. JCI Insight. 2016. April 7;1(4):e86055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zraika S, Hull RL, Udayasankar J, et al. Glucose- and time-dependence of islet amyloid formation in vitro. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2007. March 2;354(1):234–239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bower RL, Yule L, Rees TA, et al. Molecular signature for receptor engagement in the metabolic peptide hormone amylin. ACS Pharmacol Transl Sci. 2018. September 14;1(1):32–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tu L-H, Serrano AL, Zanni MT, Raleigh DP. Mutational analysis of preamyloid intermediates: the role of his-tyr interactions in islet amyloid formation. Biophys J. 2014. April 1;106(7):1520–1527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Marek P, Woys AM, Sutton K, Zanni MT, Raleigh DP. Efficient microwave-assisted synthesis of human islet amyloid polypeptide designed to facilitate the specific incorporation of labeled amino acids. Org Lett. 2010. November 5;12(21):4848–4851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Abedini A, Raleigh DP. Incorporation of pseudoproline derivatives allows the facile synthesis of human IAPP, a highly amyloidogenic and aggregation-prone polypeptide. Org Lett. 2005. February 17;7(4):693–696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tu L-H, Raleigh DP. Role of aromatic interactions in amyloid formation by islet amyloid polypeptide. Biochemistry. 2013. January 15;52(2):333–242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.LeVine H Quantification of beta-sheet amyloid fibril structures with thioflavin T. Methods Enzymol. 1999;309:274–284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wang F, Hull RL, Vidal J, Cnop M, Kahn SE. Islet amyloid develops diffusely throughout the pancreas before becoming severe and replacing endocrine cells. Diabetes. 2001. November 1;50(11):2514–2520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Eizirik DL, Flodström M, Karlsen AE, Welsh N. The harmony of the spheres: inducible nitric oxide synthase and related genes in pancreatic beta cells. Diabetologia. 1996. August;39(8):875–890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Donath MY, Böni-Schnetzler M, Ellingsgaard H, Halban PA, Ehses JA. Cytokine production by islets in health and diabetes: cellular origin, regulation and function. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2010. May;21(5):261–267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Stienstra R, Joosten LAB, Koenen T, et al. The inflammasome-mediated caspase-1 activation controls adipocyte differentiation and insulin sensitivity. Cell Metab. 2010. December 1;12(6):593–605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Vandanmagsar B, Youm Y-H, Ravussin A, et al. The NLRP3 inflammasome instigates obesity-induced inflammation and insulin resistance. Nat Med. 2011. February;17(2):179–188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kahn SE, Verchere CB, Andrikopoulos S, et al. Reduced amylin release is a characteristic of impaired glucose tolerance and type 2 diabetes in Japanese Americans. Diabetes. 1998. April;47(4):640–645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hull RL, Shen Z-P, Watts MR, et al. Long-term treatment with rosiglitazone and metformin reduces the extent of, but does not prevent, islet amyloid deposition in mice expressing the gene for human islet amyloid polypeptide. Diabetes. 2005. July;54(7):2235–2244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Aston-Mourney K, Subramanian SL, Zraika S, et al. One year of sitagliptin treatment protects against islet amyloid-associated β-cell loss and does not induce pancreatitis or pancreatic neoplasia in mice. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2013. August 15;305(4):E475–E484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cardozo AK, Ortis F, Storling J, Feng Y-M, Rasschaert J, Tonnesen M, et al. Cytokines downregulate the sarcoendoplasmic reticulum pump Ca2+ ATPase 2b and deplete endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+, leading to induction of endoplasmic reticulum stress in pancreatic β-cells. Diabetes. 2005. February;54(2):452–461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cannon JG, van der Meer JW, Kwiatkowski D, et al. Interleukin-1β in human plasma: optimization of blood collection, plasma extraction, and radioimmunoassay methods. Lymphokine Res. 1988;7(4):457–467. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Testa M, Yeh M, Lee P, et al. Circulating levels of cytokines and their endogenous modulators in patients with mild to severe congestive heart failure due to coronary artery disease or hypertension. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1996. October;28(4):964–971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Badman MK, Pryce RA, Chargé SBP, Morris JF, Clark A. Fibrillar islet amyloid polypeptide (amylin) is internalised by macrophages but resists proteolytic degradation. Cell Tissue Res. 1998. January 1;291(2):285–294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.