Abstract

Purpose

Cerebrotendinous xanthomatosis (CTX) is a treatable hereditary disorder caused by the deficiency of sterol 27- hydroxylase, which is encoded by the CYP27A1 gene. Different newborn screening biomarkers for CTX have been described, including 7α,12α-dihydroxy-4-cholesten-3-one ( 7α12αC4 ), 5b-cholestane-3 α, 7α,12α,25-tetrol glucuronide(GlcA-tetrol), GlcA-tetrol to tauro-chenodeoxycholic acid (t-CDCA) ratio (GlcA-tetrol/t-CDCA), and tauro- trihydroxycholestanoic acid (t-THCA) to GlcA-tetrol ratio (t-THCA/GlcA-tetrol ). We set out to evaluate these screening methods in a research study using 32,000–55,000 newborn dried blood spots (DBS).

Method

Metabolites were extracted from DBS with methanol containing internal standard, which was then quantified by ultra-performance liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry (UPLC-MS/MS).

Results

The measurement of 7α12αC4 was complicated by isobaric interferences and was discontinued after 2,033 samples. A total of 55,250 newborns were screened for the GlcA-tetrol/t-CDCA ratio, 32,737 of which had quantitative data on GlcA-tetrol. Only one newborn displayed both highly elevated GlcA-tetrol and a typical CTX biochemical profile. This newborn was interpreted as a CTX-affected patient as CYP27A1 gene sequencing identified two known pathogenic variants.

Conclusion

The results indicate that both GlcA-tetrol and GlcA-tetrol/t-CDCA ratio are excellent CTX biomarkers suitable for newborn screening. By characterizing the relationship of GlcA-tetrol, t-CDCA, and t-THCA as secondary markers, 100% assay specificity can be achieved.

Keywords: cerebrotendinous xanthomatosis, CYP27A1, newborn screening, biomarker, biomarker ratio

Introduction

Cerebrotendinous xanthomatosis (CTX; OMIM #213700) is a rare autosomal recessive disorder associated with the deficiency of sterol 27-hydroxylase, which is encoded by the CYP27A1 gene.1 Sterol 27-hydroxylase is involved in the biosynthesis of the primary bile acids, cholic acid (CA) and chenodeoxycholic acid (CDCA), from cholesterol.1 Biallelic pathogenic CYP27A1 variants result in deficiency of the primary bile acids, CA and CDCA, and the accumulation of bile acid pathway intermediates and derived metabolites, such as cholestanol and bile alcohols. This causes a progressive, mainly neurological phenotype. Symptoms during infancy and childhood can include neonatal cholestasis, liver failure, intractable diarrhea, bilateral cataracts and developmental delay.2, 3 CTX in adults is characterized by the development of tendon xanthomas and progressive neuropsychiatric symptoms, including pyramidal and cerebellar signs, peripheral neuropathy and dementia from the second or third decade onward. The development of symptoms can be halted or prevented by supplementation with CDCA, which downregulates both bile acid and cholesterol synthesis through a negative feedback mechanism, thereby preventing the accumulation of cholesterol and cholestanol.4 The prognosis of CTX is good when therapy is started early, but is less favorable when initiated at a later age.5 Unfortunately, due to the slow progressive nature of CTX, there is often a long diagnostic delay which negatively affects the treatment outcome of patients as irreversible neurological damages have already occurred. Based on allele frequencies of proven pathogenic variants, CTX is believed to be underdiagnosed.6 Since an early start of therapy can prevent the neurological phenotype completely, and patients are expected to remain symptom-free if treatment is started immediately after neonatal diagnosis, CTX is considered to be an excellent candidate disease for newborn screening programs.3, 5, 7, 8

Disease associated metabolites (and metabolite ratios) have been successfully used to test newborn dried blood spots (DBS) for CTX.9, 10 DeBarber et al. demonstrated that 7α,12α-dihydroxy-4-cholesten-3-one (7α12αC4), a bile acid synthesis intermediate known to be elevated in CTX, could be successfully used to identify newborns that developed CTX later in life (CTX newborns).9 Quantification of 7α12αC4 was performed with a derivatization step to improve LC-MS/MS method sensitivity, or more recently, without derivatization but using a more sensitive LC-MS/MS instrument.7, 9 The second CTX newborn screening method was described by Vaz et al. and is based on measuring the amount of a bile alcohol, 5β-cholestane-3α,7α,12α,25-tetrol glucuronide (GlcA-tetrol), as well as the ratio of GlcA-tetrol to tauro-chenodeoxycholic acid (t-CDCA) in DBS using flow-injection MS/MS.10 It was also recommended to measure the tauro-trihydroxycholestanoic acid (t-THCA) level and calculate the t-THCA/GlcA-tetrol ratio as a secondary disease indicator to distinguish CTX patients from cholestasis and Zellweger patients.10, 11

In this study, we evaluated both the practical analytical aspects and the newborn screening potential for these metabolites and metabolite ratios in a research study using DBS from >55,000 de-identified newborns.

Materials and Methods

DBS samples

This study using DBS from de-identified newborns was approved by the Washington State Institutional Review Board. DBS were shared by the Washington State Department of Health (WA DOH) after being stored for 30–60 days of life at room temperature (DBS store < 30 days cannot be shared for research according to the policy of the WA DOH). De-identified DBS from 1 CTX newborn, 8 symptomatic CTX patients and 1 Zellweger patients were acquired from the Oregon Health and Science University and the Amsterdam UMC, location AMC (Amsterdam, The Netherlands). Results from these patients and random newborns are summarized in Table S1. K2EDTA whole blood was collected from a consenting healthy adult. Negative control DBS were prepared by spotting the K2EDTA whole blood on Whatmann 903 protein saver cards (Standard Operating Protocol, Supplementary Information). Positive control DBS (GlcA-tetrol-spiked DBS) were prepared by diluting GlcA-tetrol stock solution in methanol 100-fold to K2EDTA whole blood and spotting the spiked blood on Whatmann 903 protein saver cards (Standard Operating Protocol, Supplementary Information).

Methods

The detailed protocol for the assay is provided in the Supplementary Information. In short, metabolites (GlcA-tetrol, t-CDCA and t-THCA) were extracted from a 3 mm DBS punch with methanol containing the internal standard (d6-GlcA-tetrol, Retrophin Inc). After a 4-hour extraction, the sample was centrifuged, and the supernatant was analyzed by ultra-performance liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry (UPLC-MS/MS), where the analytes and the internal standard were detected by multiple reaction monitoring (MRM) in negative electrospray ionization mode. Chromatographic peaks were integrated automatically using the TargetLynx software (Waters Corp.) and were inspected manually.

The concentration of GlcA-tetrol in blood (nM) was calculated by multiplying the ion ratio of the analyte to the internal standard by the nmole of the internal standard added to the assay, then dividing by the volume of blood (L), assuming each 3 mm DBS punch contained 3.2 μL blood. The GlcA-tetrol/t-CDCA biomarker ratio was calculated by dividing the integral area of the GlcA-tetrol peak by that of the t-CDCA peak. The t-THCA/GlcA-tetrol biomarker ratio was calculated by dividing the integral area of the t-THCA peak by that of the GlcA-tetrol peak.

Next generation sequencing of the CYP27A1 gene was conducted on a second 3 mm DBS punch from newborns that were considered to be at risk of CTX at Molecular Vision Laboratory (Hillsboro, OR).

Results

Analysis of 7α12αC4 concentration in DBS

A new derivatization method using O-ethylhydroxylamine was developed to improve the MS/MS response of 7α12αC4 (details provided in the Supplementary Information), since the original method developed by DeBarber et al. utilized a commercial kit that is too costly for large-scale screening. 7α12αC4 was derivatized via oxime bond formation, which led to a 3-fold increase in the detector response when compared to underivatized 7α12αC4. Although the original derivatization method was two times more sensitive, derivatization with O-ethylhydroxylamine afforded sufficient signal on our platform.

The 7α12αC4 concentration in DBS from 8 CTX patients, 1 CTX newborn, 1 Zellweger patient and 2,033 random newborns is shown in Fig. S1 and Table S1. During the study, however, it became apparent that the quantification of O-ethylhydroxylamine derivatized 7α12αC4 in newborn DBS suffered from interference of isobaric species eluting closely to the target compound. The abundance of these blood-derived isobars varied greatly between newborns, though they did not pose as a major issue when analyzing patient DBS. Therefore, accurate quantification of the derivatized 7α12αC4 was impossible without considerably lengthening the analysis to fully separate the interference from the analyte. We decided to discontinue the quantification of 7α12αC4 and to focus on the quantification of GlcA-tetrol and the determination of the GlcA-tetrol/t-CDCA ratio.

Analysis of GlcA-tetrol concentration and GlcA-tetrol/t-CDCA ratio in DBS

GlcA-tetrol, t-CDCA and t-THCA were simultaneously extracted from the DBS and analyzed without derivatization by UPLC-MS/MS using negative electrospray ionization mode. The sample injection-to-injection time was 2.5 minutes, allowing more than 400 samples to be analyzed per day per instrument. Fig. S2 shows the UPLC-MS/MS chromatogram of GlcA-tetrol, t-CDCA, and t-THCA in a CTX newborn, a single normal newborn, and a Zellweger patient. GlcA-tetrol was highly elevated in the CTX newborn, whereas it was undetectable in the normal newborn. The Zellweger patient showed a moderate GlcA-tetrol peak that was 4.5-fold smaller than that in the CTX newborn. t-CDCA was reduced by 5- to 7-fold in the CTX newborn and the Zellweger patient compared to the normal newborn. t-THCA was highly elevated in the Zellweger patient and undetectable in the CTX newborn and the normal newborn. Biomarker levels and biomarker ratios measured in the CTX and Zellweger patients as well as the 32,737 newborns are summarized in Table S1.

Quantification of GlcA-tetrol was carried out using d6-GlcA-tetrol as the internal standard. The linearity of the analyte assay response and the analyte recovery were assessed using a series of GlcA-tetrol-spiked DBS ranging from 0 nM to 2,000 nM. As shown in Fig. S3, the assay displayed good linearity (R2>0.99), with an overall recovery of 71% based on the slope of the calibration curve. The limit of detection for the GlcA-tetrol assay was estimated to be 38 nM, which was calculated as described (details provided in Supplementary Information).12 The assay also displayed good intra- and inter-assay imprecision (<10%), which was evaluated using adult DBS spiked with 2000 nM GlcA-tetrol, with 10 replicates measured on 5 non-consecutive days (Table S2). We did not investigate the stability of GlcA-tetrol in DBS, as previous studies demonstrated that GlcA-tetrol is stable for at least 3 weeks in DBS stored at room temperature.7, 10 This stability study is adequate for our studies since the DBS were stored for up to 1–2 months at room temperature prior to analysis. No external calibration was used in our routine analysis; the GlcA-tetrol concentration in DBS was calculated using the internal standard. Positive control and negative control (adult) DBS, with/without 2000 nM GlcA-tetrol-spike, were included in our daily analysis to ensure the consistency of the assay (Standard Operating Protocol, Supplementary Information).

Fig. S4 displays the GlcA-tetrol/t-CDCA ratio in 8 CTX patients (median: 15.51, range: 2.20–63.64), 1 CTX newborn (1.18), 1 Zellweger patient (0.38) and 2,000 random newborns (median: 0.01, range: 0–0.26). The GlcA-tetrol/t-CDCA ratio in random newborns did not vary substantially and was close to zero because GlcA-tetrol was barely detectable in most newborns, while t-CDCA was abundant. On the contrary, the GlcA-tetrol/t-CDCA ratio varied over a large range in CTX patients and CTX newborns because t-CDCA, the denominator of the ratio, was reduced to values close to zero. Compared to the 2,000 random newborns, the GlcA-tetrol/t-CDCA ratio was elevated significantly in the CTX patients and the CTX newborn, while only elevated moderately in the Zellweger patient (Fig. S4).

GlcA-tetrol as the primary screening marker for CTX

First, we used the GlcA-tetrol concentration as the primary screening filter. The screening cut-off was set at 500 nM based on the data on the GlcA-tetrol concentration in DBS from 3 CTX newborns reported by DeBarber et al. (638.9–1176 nM).7 Newborns with GlcA-tetrol concentration above the cut-off were considered at risk of CTX. A total of 32,737 newborns were screened, 6 of which (0.018%) had elevated GlcA-tetrol above the 500 nM cut-off (Table 1). Results from these 6 newborns are summarized in Table 2.

Table 1.

Summary of the results using different screening strategies.

| Method | No. of newborns screened | Cut-off | No. of newborns above the cut-off | No. of CTX screen positive after secondary filtering |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GlcA-tetrol | 32,737 | 500 nM | 6 | 1a |

| GlcA-tetrol/t-CDCA | 32,737 | 0.3 | 10 | 1a |

The same newborn was identified through these different screening strategies and was confirmed to be CTX-affected through CYP27A1 gene sequencing.

Table 2.

Summary of the results from the 6 newborns with GlcA-tetrol concentration above the 500 nM screening cut-off.

| GlcA-tetrol (nM) | GlcA-tetrol/t-CDCA | t-THCA/GlcA-tetrol | t-CDCA peak area | t-THCA peak area | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Subject 1 | 1396.03 | 0.02 | 0.42 | 24731 | 210 |

| Subject 2 | 1384.01 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 19249 | 8 |

| Subject 3a | 1072.32 | 14.82 | 0.03 | 22 | 9 |

| Subject 4 | 982.22 | 0.01 | 1.67 | 22078 | 368 |

| Subject 5b | 599.63 | 0.46 | 9.88 | 394 | 1791 |

| Subject 6 | 504.34 | 0.08 | 0.99 | 2582 | 204 |

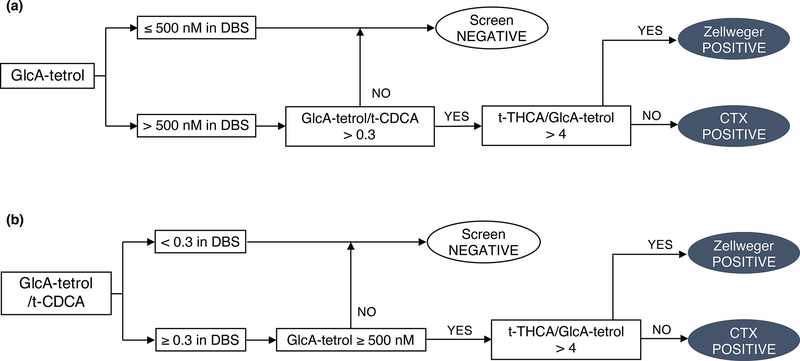

To further improve the specificity of the screening, GlcA-tetrol/t-CDCA and t-THCA/GlcA-tetrol ratios were implemented as secondary screening markers. The proposed screening algorithm for CTX is shown in Fig. 1a. Only newborns displaying both elevated GlcA-tetrol concentration and GlcA-tetrol/t-CDCA ratio were considered as screen positives (Fig. 1a). Since an elevated t-THCA/GlcA-tetrol ratio was indicative of Zellweger disorder, this metabolite ratio was used to distinguish CTX screen positives from Zellweger screen positives (Fig. 1a).10 The cut-off for the GlcA-tetrol/t-CDCA ratio was set at 0.3, based on the results reported in this study (1 CTX newborn, 1.18, Table S1) and in literatures (5 CTX newborns, 0.33–138).7, 10 The cut-off for the t-THCA/GlcA-tetrol ratio was set at 4, based on results reported in this study (1 Zellweger patient, 11.8, Table S1) and in the literature (3 Zellweger patients, 10.5 to 38).10

Fig. 1.

Proposed algorithms for the newborn screening of CTX. (a) GlcA-tetrol as the primary marker and GlcA-tetrol/t-CDCA and t-THCA/GlcA-tetrol ratios as the secondary markers. (b) GlcA-tetrol/t-CDCA ratio as the primary marker and GlcA-tetrol and t-THCA/GlcA-tetrol ratio as the secondary markers.

Following this algorithm, only 2 out of the 6 newborns with elevated GlcA-tetrol had GlcA-tetrol/t-CDCA ratio above 0.3 (subject 3 and 5, Table 2). The rest were not considered to be potential CTX patients after applying the GlcA-tetrol/t-CDCA ratio as the secondary filter. In addition, the t-CDCA peaks in subjects 1, 2 and 4 (Table 2) were higher than 99.9% of the newborns screened in the study, suggesting cholestasis.7, 13 Subject 5 (Table 2) had both moderately elevated GlcA-tetrol (599.6 nM) and GlcA-tetrol/t-CDCA ratio (0.46) but highly elevated t-THCA/GlcA-tetrol ratio (9.88), suggesting Zellweger syndrome. No discernable t-THCA peak was found in subject 2 and 3, whereas t-THCA was slightly elevated in subjects 1, 4 and 6 (Table 2). Thus, only subject 3 in Table 2 fits the biochemical profile of CTX and was considered to be CTX screen positive.

This single newborn (subject 3, Table 2) that was suggested to be CTX-affected based on the absolute abundance of GlcA-tetrol as well as GlcA-tetrol/t-CDCA and t-THCA/GlcA-tetrol ratios was submitted to genotyping using a reserved 3 mm punch from the same DBS used for the UPLC-MS/MS analysis. DNA sequencing of the CYP27A1 gene revealed two known pathogenic variants: NM_000784.3(CYP27A1):c.1214G>A (p.Arg405Gln) and NM_000784.3(CYP27A1):c.1415G>C (p.Gly472Ala).6 Therefore, subject 3 in Table 2 was interpreted as a CTX patient.

GlcA-tetrol/t-CDCA ratio as the primary screening marker for CTX

Alternatively, the GlcA-tetrol/t-CDCA ratio could also be used as the primary screening marker for CTX. The screening cut-off was set at 0.3 (see previous section). Newborns with a GlcA-tetrol/t-CDCA ratio above 0.3 were considered at risk of CTX. Among the 32,737 newborns, 10 (0.031%) displayed a GlcA-tetrol/t-CDCA ratio above the cut-off. Results from these 10 newborns are summarized in Table 3.

Table 3.

Summary of the results from the 10 newborns with GlcA-tetrol/t-CDCA ratio above 0.3.

| GlcA-tetrol (nM) | GlcA-tetrol/t-CDCA | t-THCA/GlcA-tetrol | t-CDCA peak area | t-THCA peak area | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Subject 1a | 1072.32 | 14.82 | 0.03 | 22 | 9 |

| Subject 2 | 42.09 | 0.5 | 0 | 22 | 0 |

| Subject 3b | 599.63 | 0.46 | 9.88 | 394 | 1791 |

| Subject 4 | 122.43 | 0.46 | 0.03 | 70 | 1 |

| Subject 5 | 141.74 | 0.36 | 0 | 28 | 0 |

| Subject 6 | 31.03 | 0.35 | 0 | 20 | 0 |

| Subject 7 | 86.35 | 0.33 | 0.11 | 54 | 2 |

| Subject 8 | 107.56 | 0.32 | 0 | 75 | 0 |

| Subject 9 | 76.31 | 0.3 | 0.1 | 96 | 3 |

| Subject 10 | 121.17 | 0.3 | 0.05 | 125 | 2 |

GlcA-tetrol concentration (cut-off: 500 nM) as well as the t-THCA/GlcA-tetrol ratio (cut-off: 4) were both implemented as secondary markers to improve the specificity of the screening. The cut-off establishment was elaborated in the previous section. The screening algorithm is shown in Fig. 1b. Following this screening algorithm, subject 1 in Table 3 (same as subject 3, Table 2) was identified as CTX screen positive and subject 3 in Table 3 (same as subject 5, Table 2) was identified as Zellweger screen positive. The remainder were considered as screen negatives. Therefore, this screening algorithm (Fig. 1b) identified the same CTX and Zellweger screen positives as the previous algorithm (Fig. 1a), indicating that the GlcA-tetrol/t-CDCA ratio is also a good first-tier marker for newborn screening of CTX.

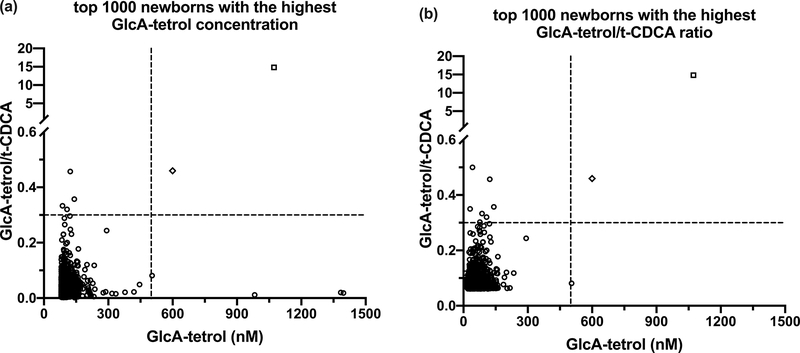

Assessment of the screening sensitivity

To evaluate the sensitivity of the screening, the GlcA-tetrol/t-CDCA ratio from the top 1,000 newborns ranked according to elevated GlcA-tetrol concentration was plotted (Fig. 2a). Fig. 2b displays the GlcA-tetrol concentration from the top 1,000 newborns ranked according to the GlcA-tetrol/t-CDCA ratio. In both cases, two newborns are found to be well separated from the remaining 998 newborns. These two are the CTX patient and the potential Zellweger patient identified as described above according to the two screening algorithms (Fig. 1). Based on this clear separation, we did not carry out CYP27A1 sequencing on additional newborns.

Fig. 2.

GlcA-tetrol/t-CDCA ratio vs GlcA-tetrol concentration from the top 1,000 newborns with the highest (a) GlcA-tetrol concentration; and (b) GlcA-tetrol/t-CDCA ratio. The horizontal dash lines indicate the GlcA-tetrol/t-CDCA ratio cut-off at 0.3. The vertical dash lines indicate the GlcA-tetrol cut-off at 500 nM. Newborns that fall into the upper-right quadrant are considered screen positives. The screen positive indicated by a diamond (⬦) is the Zellweger screen positive (subject 5 in Table 2, subject 3 in Table 3). The screen positive indicated by a square (□) is the CTX screen positive (subject 3 in Table 2, subject 1 in Table 3).

Discussion

7α12αC4 was not considered to be useful as a primary marker for CTX in this study due to the endogenous interferences using our derivatization approach and the requirement for a short analysis time per newborn. However, it should be noted that the isobar problem can be resolved by using an enhanced gradient to fully separate the derivatized 7α12αC4 from the isobars or by quantifying the marker without derivatization using a less sensitive but more specific MRM channel as described by DeBarber et al.7 This requires a longer sample turnaround time and/or a more sophisticated mass spectrometer. Nevertheless, measurement of 7α12αC4 can still be used in the future as a secondary biomarker. In our study, we had only 1 reserved DBS punch after the first-tier UPLC-MS/MS analysis, and we opted to use it for genotyping analysis.

The GlcA-tetrol/t-CDCA ratio and GlcA-tetrol from the CTX newborn were significantly elevated compared to random newborns, but they were less elevated than levels measured in older, untreated CTX patients (Fig. S4 and Table S1). Similar trends were seen in previous reports.7, 10 Although little is known about the correlation between blood glucuronide-conjugated bile alcohol concentration and age, it is well established that glucuronidation capacity is low in neonates because of the low activity of UDP-glucuronosyltransferase, which increases with age.14 This likely leads to lower glucuronide-conjugated bile alcohol levels in neonates, which explains the lower GlcA-tetrol concentration seen in CTX newborns compared to older CTX patients. In addition, it was reported that in neonates the serum t-CDCA concentration is higher than that in children and adolescents.15 Together, this would explain the lower GlcA-tetrol/t-CDCA ratios observed in CTX newborns compared to older CTX patients, as the GlcA-tetrol/t-CDCA ratios in CTX newborns are calculated by dividing the lower GlcA-tetrol level by the higher t-CDCA level. As all newborns have lower blood concentrations of GlcA-tetrol in combination with lower GlcA-tetrol/t-CDCA ratios, we do not expect a negative effect on the discriminative power of the CTX newborn screening method described here.

GlcA-tetrol was found to be an excellent marker for CTX, as only 6 out of 32,737 newborns (0.018%) had a GlcA-tetrol level above the 500 nM screening cut-off. The screen-positive rate was further reduced when GlcA-tetrol/t-CDCA and t-THCA/GlcA-tetrol ratios were taken into consideration. Since t-CDCA and t-THCA are extracted together with GlcA-tetrol, there is no need for an additional DBS punch nor a separate analysis. Only 1 out of 32,737 newborns was considered to be at risk of CTX after applying the GlcA-tetrol/t-CDCA and t-THCA/GlcA-tetrol ratios as secondary screening markers. CYP27A1 gene sequencing of the newborn of interest revealed two pathogenic variants, showing 100% assay specificity.

One concern with the 500 nM GlcA-tetrol screening cut-off is that it is based on published data from only 3 CTX newborns, and it is difficult to rule out the possibility of false negatives in the future. However, even if the cut-off for GlcA-tetrol is lowered from 500 nM to 300 nM, only 11 out of the 32,737 (0.034%) newborns would result. If the cut-off for the secondary marker, GlcA-tetrol/t-CDCA ratio, is lowered from 0.3 to 0.2, this would result in only 2 out of the 11 newborns (same as the subject 3 and 5 in Table 2), one of which is the suspected Zellweger patient and can be identified by using the t-THCA/GlcA-tetrol ratio. This gives us confidence that even in extreme cases where the screening cut-offs for GlcA-tetrol and GlcA-tetrol/t-CDCA need to be lowered significantly, the false-positive rate is not expected to increase substantially. Data from future prospective pilot studies and CTX-affected newborns identified will help to better define the affected range and confirm the optimal cut-off for GlcA-tetrol concentration and the GlcA-tetrol/t-CDCA ratio.

Alternatively, using the GlcA-tetrol/t-CDCA ratio as the first-tier screening marker is also feasible based on our results. The screen-positive rate using GlcA-tetrol/t-CDCA ratio as the primary marker is 0.031% and is acceptable for a newborn screening test compared to other active newborn screening programs.16–18 By implementing GlcA-tetrol and t-THCA/GlcA-tetrol as secondary markers, the screen-positive rate can be further reduced, as shown in this study. Vaz et al. originally proposed to screen CTX by measuring the GlcA-tetrol/t-CDCA ratio using flow-injection MS/MS without using an internal standard.10 The benefit of this approach is that most screening laboratories are only equipped with flow-injection MS/MS, not LC-MS/MS. Most flow-injection MS/MS based screening tests (i.e. amino acid, acyl-carnitine and succinylacetone analysis), however, are carried out in positive electrospray ionization mode in contrast to the negative mode required for our CTX screening assay. This necessitates a separate analysis for CTX. Furthermore, endogenous isobars with GlcA-tetrol and t-CDCA can skew the result of flow-injection MS/MS analysis, which is the case for the quantification of C26:0-lysophosphatidylcholine for X-linked adrenoleukodystrhophy.19 It remains to be established how this will affect the results for CTX screening, and the flow-injection MS/MS method needs to be tested in a larger newborn population. Even if flow-injection MS/MS is used as the first-tier NBS test, a secondary LC-MS/MS analysis with suitable internal standards is expected to be required to quantify GlcA-tetrol, t-CDCA, and t-THCA.

One advantage of quantifying the absolute concentration of GlcA-tetrol using a chemically identical but isotopic differentiated internal standard is that the screening cut-off is expected to be comparable across multiple platforms and between laboratories. Researches who are interested in setting up the assay can contact A. DeBarber (debarber@ohsu.edu) for the reagents (GlcA-tetrol and d6-GlcA-tetrol). It should also be noted that, in this study, the GlcA-tetrol/t-CDCA ratio was calculated by dividing the integral peak area of GlcA-tetrol by that of t-CDCA. Since GlcA-tetrol and t-CDCA did not co-elute on the UPLC column (Fig. S2), they are expected to suffer from different extents of matrix effects (ion-suppression). For flow-injection MS/MS analysis, this issue is less relevant as analytes all pass into the mass spectrometer together, though it can suffer from interference from isobars. Therefore, the measured GlcA-tetrol/t-CDCA ratio (and affected range) may differ between LC-MS/MS methods and flow-injection MS/MS methods. Although not used in the current study, deuterated t-CDCA is commercially available from Toronto Research Chemicals (Cat. T008133), and some assay improvement may result if the GlcA-tetrol/t-CDCA ratio is calculated by dividing the measured GlcA-tetrol/d6-GlcA-tetrol ratio by the measured t-CDCA/deuterated t-CDCA ratio.

Conclusion

The research study presented here demonstrates that newborn screening for CTX is feasible with an exceptionally low false-positive rate. We propose that CTX be screened based on either the GlcA-tetrol concentration or the GlcA-tetrol/t-CDCA ratio in DBS. A comprehensive profiling of GlcA-tetrol, t-CDCA, and t-THCA is required as a secondary filter to improve the specificity of the screening. Among the 32,737 random newborns screened, only one had a biochemical abnormality -as defined in this study- that was indicative of CTX. DNA sequencing of the CYP27A1 gene revealed two previously reported pathogenic variants, and together with the biochemical data, strongly suggests that this newborn will develop CTX disease. Our study demonstrated that newborn screening for CTX is feasible in a real-world scenario.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Retrophin, Inc. for providing the internal standard d6-GlcA-tetrol. This work was supported by a grant from the National Institutes of Health (R01 DK067859).

Footnotes

M. Gelb is a consultant with PerkinElmer Corp. All other authors have no conflicts to declare.

Disclosure

F.M. Vaz filed patents include EP3593143, CN110612448, CA3055659, AU2018231379. M.H. Gelb is a cofounder of GelbChem, LLC, and a consultant for PerkinElmer. Awarded and filed patents include US20140249054A1, US20160298166A1, US8802833B2, EP2191006B1, and EP2385950B1.

Reference

- 1.Verrips A; Hoefsloot LH; Steenbergen GC; Theelen JP; Wevers RA; Gabreëls FJ; van Engelen BG; van den Heuvel LP, Clinical and molecular genetic characteristics of patients with cerebrotendinous xanthomatosis. Brain 2000, 123 (5), 908–919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gong J-Y; Setchell KD; Zhao J; Zhang W; Wolfe B; Lu Y; Lackner K; Knisely A; Wang N-L; Hao C-Z, Severe neonatal cholestasis in cerebrotendinous xanthomatosis: genetics, immunostaining, mass spectrometry. Journal of pediatric gastroenterology and nutrition 2017, 65 (5), 561–568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Salen G; Steiner RD, Epidemiology, diagnosis, and treatment of cerebrotendinous xanthomatosis (CTX). J Inherit Metab Dis 2017, 40 (6), 771–781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pierre G; Setchell K; Blyth J; Preece MA; Chakrapani A; Mckiernan P, Prospective treatment of cerebrotendinous xanthomatosis with cholic acid therapy. Journal of inherited metabolic disease 2008, 31 (2), 241–245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yahalom G; Tsabari R; Molshatzki N; Ephraty L; Cohen H; Hassin-Baer S, Neurological outcome in cerebrotendinous xanthomatosis treated with chenodeoxycholic acid: early versus late diagnosis. Clin Neuropharmacol 2013, 36 (3), 78–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Appadurai V; DeBarber A; Chiang PW; Patel SB; Steiner RD; Tyler C; Bonnen PE, Apparent underdiagnosis of Cerebrotendinous Xanthomatosis revealed by analysis of ~60,000 human exomes. Mol Genet Metab 2015, 116 (4), 298–304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.DeBarber AE; Kalfon L; Fedida A; Fleisher Sheffer V; Ben Haroush S; Chasnyk N; Shuster Biton E; Mandel H; Jeffries K; Shinwell ES; Falik-Zaccai TC, Newborn screening for cerebrotendinous xanthomatosis is the solution for early identification and treatment. J Lipid Res 2018, 59 (11), 2214–2222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Berginer VM; Gross B; Morad K; Kfir N; Morkos S; Aaref S; Falik-Zaccai TC, Chronic diarrhea and juvenile cataracts: think cerebrotendinous xanthomatosis and treat. Pediatrics 2009, 123 (1), 143–147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.DeBarber AE; Luo J; Star-Weinstock M; Purkayastha S; Geraghty MT; Chiang JP; Merkens LS; Pappu AS; Steiner RD, A blood test for cerebrotendinous xanthomatosis with potential for disease detection in newborns. J Lipid Res 2014, 55 (1), 146–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vaz FM; Bootsma AH; Kulik W; Verrips A; Wevers RA; Schielen PC; DeBarber AE; Huidekoper HH, A newborn screening method for cerebrotendinous xanthomatosis using bile alcohol glucuronides and metabolite ratios. Journal of lipid research 2017, 58 (5), 1002–1007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gustafsson J; Sisfontes L; Björkhem I, Diagnosis of Zellweger syndrome by analysis of bile acids and plasmalogens in stored dried blood collected at neonatal screening. The Journal of pediatrics 1987, 111 (2), 264–267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Armbruster DA; Pry T, Limit of blank, limit of detection and limit of quantitation. The clinical biochemist reviews 2008, 29 (Suppl 1), S49. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mills KA; Mushtaq I; Johnson AW; Whitfield PD; Clayton PT, A method for the quantitation of conjugated bile acids in dried blood spots using electrospray ionization-mass spectrometry. Pediatric research 1998, 43 (3), 361–368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Neumann E; Mehboob H; Ramirez J; Mirkov S; Zhang M; Liu W, Age-Dependent Hepatic UDP-Glucuronosyltransferase Gene Expression and Activity in Children. Front Pharmacol 2016, 7, 437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jahnel J; Zohrer E; Scharnagl H; Erwa W; Fauler G; Stojakovic T, Reference ranges of serum bile acids in children and adolescents. Clin Chem Lab Med 2015, 53 (11), 1807–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hopkins PV; Klug T; Vermette L; Raburn-Miller J; Kiesling J; Rogers S, Incidence of 4 lysosomal storage disorders from 4 years of newborn screening. JAMA pediatrics 2018, 172 (7), 696–697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Burton BK; Charrow J; Hoganson GE; Waggoner D; Tinkle B; Braddock SR; Schneider M; Grange DK; Nash C; Shryock H; Barnett R; Shao R; Basheeruddin K; Dizikes G, Newborn Screening for Lysosomal Storage Disorders in Illinois: The Initial 15-Month Experience. J Pediatr 2017, 190, 130–135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lee S; Clinard K; Young SP; Rehder CW; Fan Z; Calikoglu AS; Bali DS; Bailey DB Jr.; Gehtland LM; Millington DS; Patel HS; Beckloff SE; Zimmerman SJ; Powell CM; Taylor JL, Evaluation of X-Linked Adrenoleukodystrophy Newborn Screening in North Carolina. JAMA Netw Open 2020, 3 (1), e1920356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Turgeon CT; Moser AB; Morkrid L; Magera MJ; Gavrilov DK; Oglesbee D; Raymond K; Rinaldo P; Matern D; Tortorelli S, Streamlined determination of lysophosphatidylcholines in dried blood spots for newborn screening of X-linked adrenoleukodystrophy. Mol Genet Metab 2015, 114 (1), 46–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.