Abstract

We report a patient presenting with clinical features of logopenic variant primary progressive aphasia (lvPPA) who was later diagnosed with probable dementia with Lewy bodies. LvPPA is a neurodegenerative disease that is characterized by anomia, word-finding difficulty, impaired comprehension, and phonological errors. The most common underlying pathology for lvPPA is Alzheimer’s disease. However, our patient with clinical features of logopenic progressive aphasia was later diagnosed with probable dementia with Lewy bodies. This case demonstrates that lvPPA can also be an initial manifestation of a phenotype of dementia with Lewy bodies.

Keywords: Logopenic progressive aphasia, dementia with Lewy bodies, Alzheimer disease, beta-amyloid (Aβ)

Introduction

Logopenic variant primary progressive aphasia (lvPPA) is a neurodegenerative disease characterized by anomia, word-finding difficulty, impaired sentence comprehension and repetition, and phonological errors (Gorno-Tempini et al., 2008). During speech, lvPPA patients may have prolonged pauses, which are also apparent with writing (Marshall et al., 2018). The most common underlying pathology for lvPPA is Alzheimer’s disease (AD) (Spinelli et al., 2017). Consistent with the pathological data, lvPPA patients were more likely to be beta-amyloid (Aβ) + with Aβ PET (86–89%), compared to the non-fluent/agrammatic (0–20%) and semantic (16–21%) variants of primary progressive aphasia (PPA) (Bergeron et al., 2018; Josephs, Duffy, Strand, Machulda, Senjem, et al., 2014).

Dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB) is a neurodegenerative disorder characterized by recurrent, fully formed visual hallucinations, Parkinsonism, cognitive fluctuations, and Rapid Eye Movement sleep-behavior disorder (McKeith et al., 2017). Pathologically, DLB is characterized by the aggregation of α-synuclein protein in Lewy bodies and Lewy neurites. In the 2017 McKeith criteria for DLB, biomarkers have an elevated importance for establishing a diagnosis with an abnormal dopamine transporter imaging or MIBG scan (McKeith, et al., 2017).

Although lvPPA is most frequently associated with AD pathology, we report a patient presenting with clinical features of lvPPA who was later diagnosed with probable DLB.

History

A 68-year-old right-handed man presented to the behavioral neurology clinic with a two-year history of progressive difficulty with self-expression. He also reported difficulty with spelling, speech pauses, and difficulty understanding complex instructions. He was able to complete the bookkeeping functions for the household, but he did not talk as much in social situations because of fear of embarrassment. On review of systems, he and his wife reported that he had a few episodes in which he acted out his dreams and talked while he slept. He enrolled in a clinical research program on progressive aphasia.

His bedside neurological exam at presentation revealed a Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) score of 26/30. He had evidence of aphasia and problems with sentence repetition and no problems recognizing famous faces. He had no evidence of limb ideomotor apraxia. There was no clear Parkinsonism with the exception of a minimally masked face. He underwent a comprehensive speech-language evaluation which revealed a score of 13/22 on the Token Test (De Renzi and Vignolo, 1962), a test of complex comprehension. With semantic fluency, he named 13 animals in 60 seconds. Letter fluency for a combined three letters (FAS) was only 13. He achieved an Aphasia Quotient of 89.8 on the Western Aphasia Battery (WAB) (Shewan and Kertesz, 1980) and was classified “anomic.” WAB Written Language Comprehension was 30/40, Reading Commands 20/20, and Written Output 30.5/34. He was able to read 10/10 irregularly spelled words but only 3/10 regularly spelled non-words. He had difficulty writing irregular words (4/10) and non-words (2/10). He scored 9/15 on the 15-item short form of the Boston Naming Test (Lansing, Ivnik, Cullum, & Randolph, 1999); he did not benefit from phonemic cues but was able to recognize 5/6 of the words that he had missed from multiple written choices. He scored 45/52 on the Pyramids and Palm Trees Test without clear evidence for loss of object knowledge. He made some phonological errors during his spontaneous speech. There was no evidence of agrammatism, apraxia of speech or non-verbal oral apraxia on examination. He underwent consensus classification by two speech-language pathologists blinded to imaging data in order to render a consensus diagnosis based on previously published criteria (Josephs et al., 2010) and was designated as having a mild-to-moderate aphasia consistent with lvPPA. Neuropsychological data is summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Neuropsychological Test Data

| Neuropsychological Test | 2012 | 2014 | 2016 |

|---|---|---|---|

| WMS-III Digit Span | - | Low average | Low average |

| WMS-III Spatial Span | - | Moderately impaired | Moderately impaired |

| Trailmaking Test A | Within normal limits | Moderately impaired | Severely impaired |

| Trailmaking Test B | Mildly impaired | Severely impaired | Severely impaired |

| AVLT Trials 1 – 5 | Severely impaired | Severely impaired | - |

| AVLT 30-minute delayed recall | Mildly impaired | Severely impaired | - |

| AVLT recognition | Chance level responding | Chance level responding | - |

| Camden Short Recognition Memory Test for Words | - | - | Severely impaired |

| WMS-III Logical Memory I | Moderately impaired | Severely impaired | - |

| WMS-III Logical Memory II | Moderately impaired | Mildly to moderately impaired | - |

| WMS-III Visual Reproduction I | Within normal limits | Low average | - |

| WMS-III Visual Reproduction II | Within normal limits | Low average | - |

| Camden Short Recognition Memory Test for Faces | - | - | Within normal limits |

| VOSP Incomplete Letters | Within normal limits | Within normal limits | Within normal limits |

| VOSP Cube Analysis | Within normal limits | Within normal limits | Severely impaired |

| Modified Wisconsin Card Sorting Test | Moderately impaired | Moderately impaired | - |

| WRAT-3 Reading | Low average | Low average | - |

WMS - The Wechsler Memory Scale

AVLT - Auditory Verbal Learning Test

VOSP - Visual Object and Space Perception Battery

WRAT-3 - Wide Range Achievement Test 3

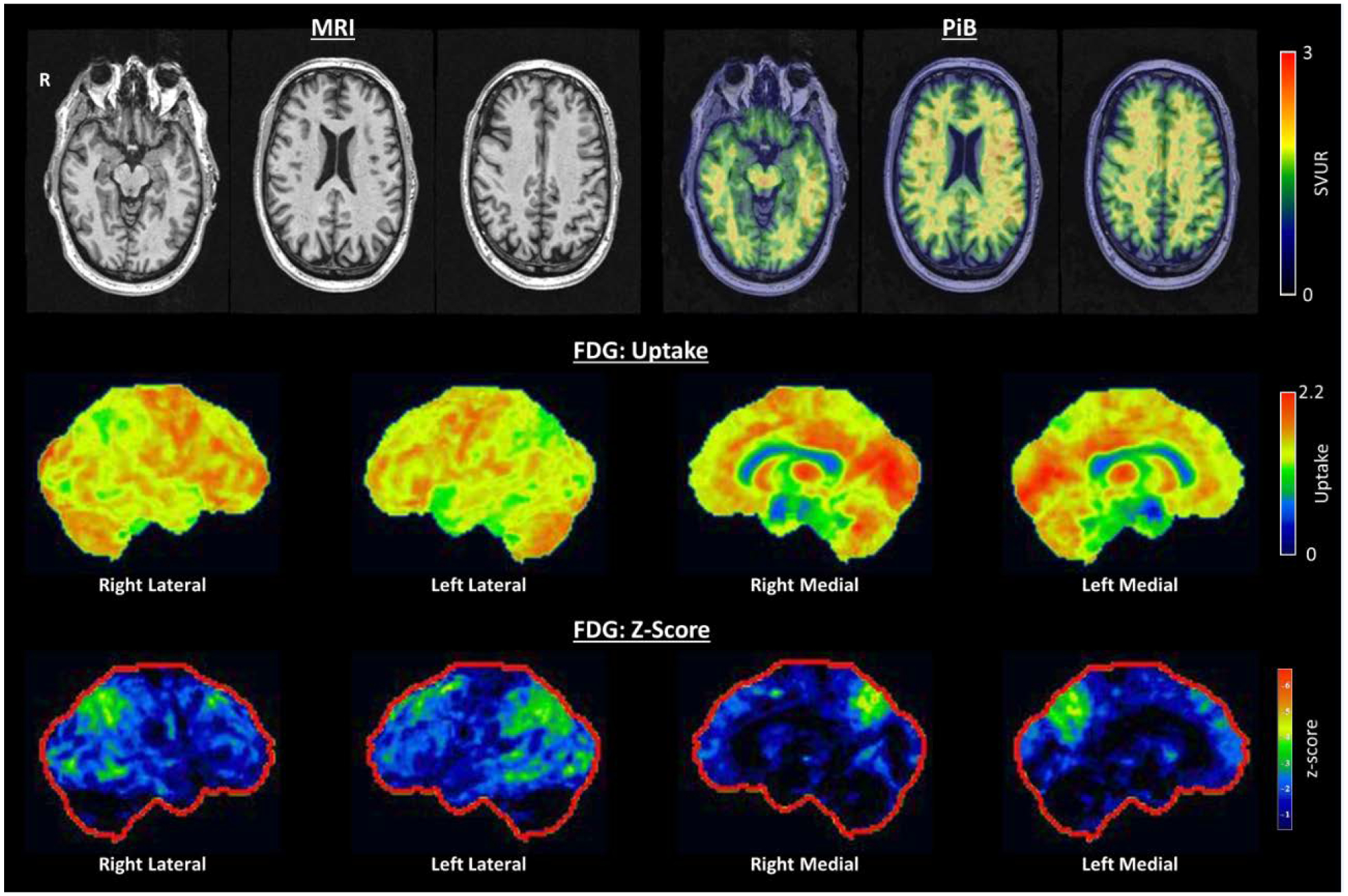

Imaging at baseline revealed minimal atrophy on MRI (see Figure 1). Aβ PET performed with Pittsburgh compound B (PiB) revealed a global standard update value ratio (SUVR) of 1.37 (positive is considered greater than 1.48) and was read as being visually negative (see Figure 1). FDG-PET revealed mild bilateral parietal>temporal hypo-metabolism, with the left hemisphere being more involved, as well as relative preservation of the posterior cingulate relative to the cuneus and precuneus (see Figure 1).

Figure 1:

Baseline neuroimaging: Top row: Axial T1 MRI demonstrating minimal atrophy, PiB PET demonstrating no significant cortical amyloid deposition. Middle Row: FDG PET uptake demonstrating preservation of the posterior cingulate relative to the precuneus and cuneus (cingulate island sign). Bottom row: FDG PET demonstrating bilateral but left greater than right parietal, temporal and occipital hypometabolism.

He underwent genetic screening for mutations in the Progranulin, Microtubule Associated Protein, Tau, and C9ORF72 gene and was negative for all three. He had a sleep medicine consultation with a neurologist, who felt his sleep history was consistent with REM sleep-behavior disorder, but he did not undergo formal polysomnography.

Two years later, he returned for re-evaluation. He had persistent word-finding difficulties. He had now developed subjective visuospatial difficulties. For example, he was unable to find his contact solution, although it was in the medicine cabinet, and he repeatedly bumped into furniture. His MMSE was 27/30, but his language exam was consistent with a progressive aphasia with poor naming and phonological errors. He had a masked face with slightly decreased alternating motion rates in the right upper and lower extremity. There was still no evidence for tremor, rigidity, or postural instability. He again underwent a detailed speech-language evaluation. He named 9/15 items on the short form of the Boston Naming Test. Aphasia Quotient of the WAB was 87.3, with a classification of anomic aphasia; Verbal repetition of words 15/20; Written Spelling of words 9/20; Written Spelling of regularly spelled non-words 1/10; Pyramids and Palm Trees 44/50.

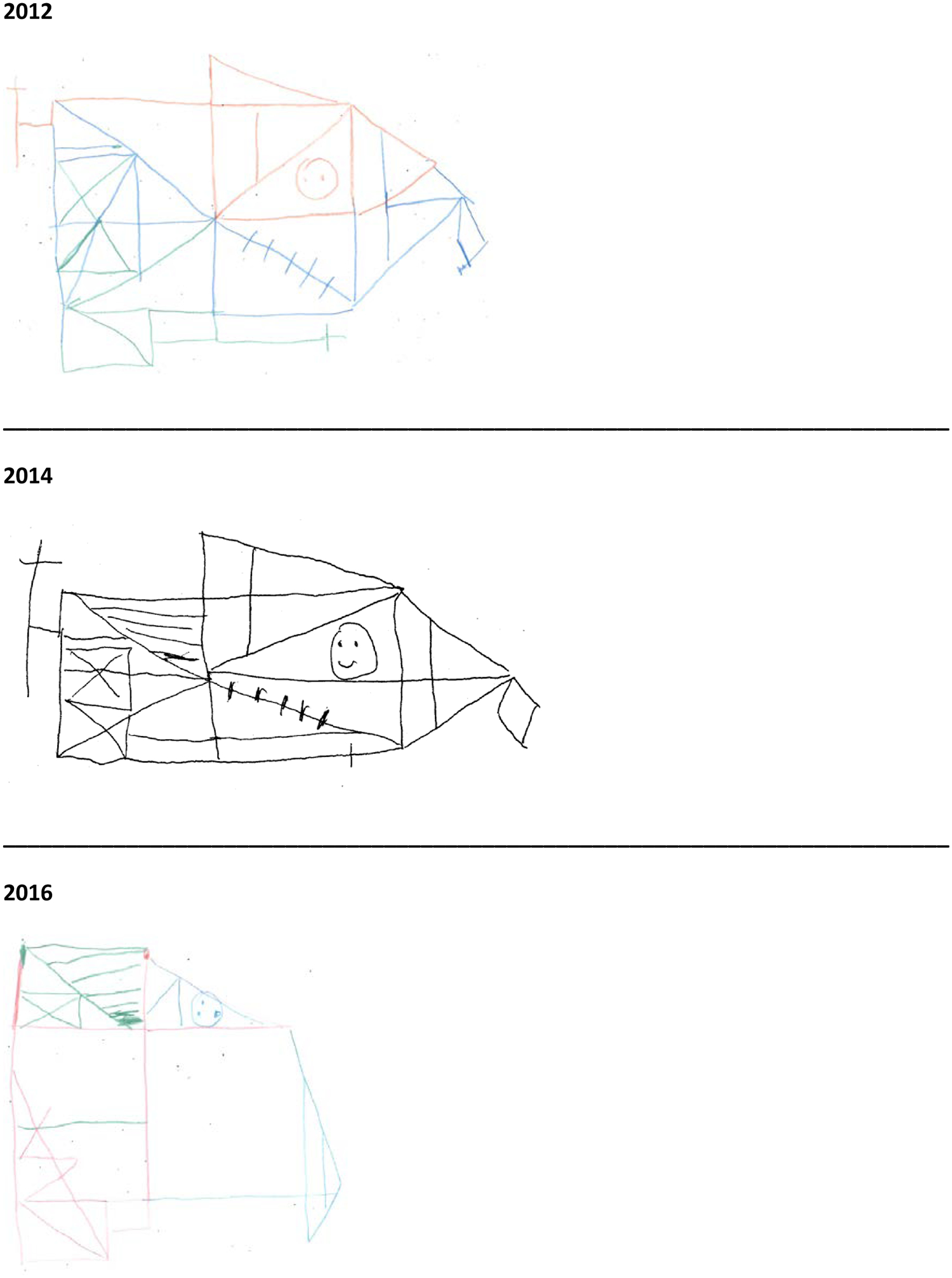

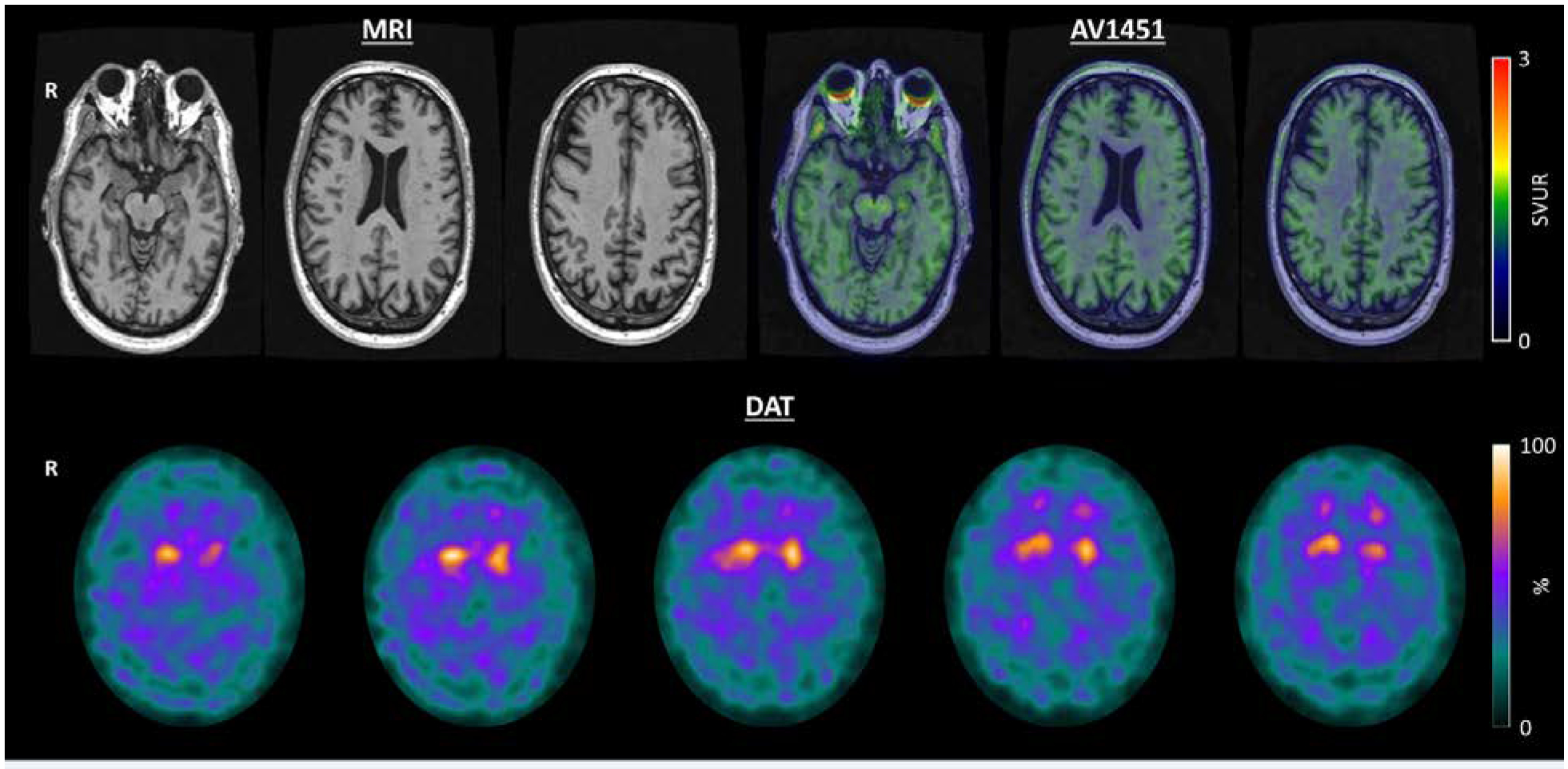

He returned again four years after presentation. At this point, he had developed objective evidence of visuospatial impairment (see Figure 2.) He underwent a flortaucipir PET scan (Figure 3) with [18F]AV-1451, which was visually interpreted as negative [SUVR 1.22, greater than 1.23 is considered positive (Jack et al., 2017)]. Because of his negative AD biomarkers, negative genetic screening, Parkinsonism, and REM sleep-behavior disorder, he underwent a DaT scan (Figure 3), which was revealing for decreased tracer uptake bilaterally in the putamen. Therefore, in the context of normal AD biomarkers and two clinical features of DLB (Parkinsonism and RBD) with an indicative biomarker, he was diagnosed with probable DLB with an atypical initial clinical presentation of lvPPA.

Figure 2:

Rey-Osterrieth Complex Figure copy drawings from each assessment.

Figure 3:

Follow-up neuroimaging: Top Row: Axial T1 MRI demonstrating minimal atrophy over 2 years of follow-up. AV1451 demonstrating an absence of abnormal cortical tau deposition. Bottom Row: Dopamine Transporter Scan demonstrating bilateral decreased uptake in the putamen

When he returned seven years after presentation, he was speaking less, and his comprehension was poor, more so for spoken language than for written language. His Parkinsonism had worsened from his prior visits and was characterized by a masked face, change in alternating motion rates consistent with small amplitude and occasional motor arrests, and overall progression of bradykinesia. Cognitive fluctuations had developed, and he was started on the Rivastigmine patch, which proved helpful for the fluctuations. He had a couple unusual behaviors, some associated with sleep, as well as episodes of confusion and lack of social interaction on awaking. A repeat FD-PET scan once again showed biparieto-occipital and frontal hypometabolism with greater involvement of the cuneus and precuneus compared to the cingulate.

Discussion

In this case report, we demonstrate that lvPPA can be the initial manifestation of a probable DLB phenotype. At initial presentation, the minimal Parkinsonism (masked face) and RBD were clues to the possible presence of α-synuclein pathology. This extends the causes of the lvPPA phenotype to include AD, stroke (Riancho et al., 2017), FTLD pathology (Mesulam et al., 2014) including progranulin mutations (Josephs, Duffy, Strand, Machulda, Vemuri, et al., 2014; Rohrer, Crutch, Warrington, & Warren, 2010), and now DLB.

Our case is similar to a case study of an individual with lvPPA who had negative AD biomarkers and later developed features consistent with DLB (Teichmann, Migliaccio, Kas, & Dubois, 2013). In both cases, the Lewy body features became more apparent with time, and the DaT scan was abnormal. While AD biomarkers were measured in the CSF in the former case, these were assessed via PiB PET and flortaucipir in the current case. Further, in our case, the FDG PET scan (2 years after initial symptom onset) showed relative preservation of the posterior cingulate gyrus relative to the cuneus and precuneus. This characteristic feature is known as the cingulate island sign, which has been reported as a biomarker supportive for DLB (McKeith, et al., 2017) and reliably distinguishes AD from DLB (Graff-Radford et al., 2014). However, the cingulate island sign has also been observed in atypical AD patients (Whitwell et al., 2017). The pattern of FDG-PET hypo-metabolism was consistent with findings reported in DLB patients (Kantarci et al., 2012).

The presence of lvPPA and REM sleep-behavior disorder could suggest dual pathologies of AD and Lewy body disease. Caselli et. al. reported a patient who presented with a progressive aphasia and, six years after presentation, developed visual hallucinations and parkinsonism. Autopsy revealed that she had both AD and Lewy body disease (Caselli, Beach, Sue, Connor, & Sabbagh, 2002). In this case, the aphasia was considered secondary to AD pathology with the later-developing Lewy body features reflecting co-pathology. Subsequent cases of patients with DLB presenting with logopenic features have been reported, and AD biomarkers were similarly positive, suggesting these cases represent a mixed phenotype from mixed pathology (Fukui, Okita, Uchiyama, Kasai, & Kinno, 2013).

In an autopsy series of lvPPA patients, 2 out of 34 were found to have Lewy body disease pathology (Giannini et al., 2017). Our cases highlight that clinical features and biomarkers may allow antemortem prediction of pathology in at least a subset of these cases.

There are several limitations that should be noted when interpreting this case report. While our case is not autopsy proven, which is a limitation of the study, the negative AD biomarkers (PiB and flortaucipir) strongly argue against AD pathology as the cause of the aphasia (Jack et al., 2018). Nonetheless, it remains a possibility, although unlikely, that the AD biomarkers were falsely negative in this case or that they may progress to become positive over time. While dopamine-transporter imaging is part of the current diagnostic criteria for DLB, abnormal dopamine-transporter imaging is not a direct biomarker of α-synuclein pathology and can reflect an abnormal number of dopamine transporters in the striatum with other parkinsonian disorders.

In cases where clinical features are suggestive of both AD and LBD, biomarkers can provide clues to the underlying etiology. While most cases in the literature suggest that patients with logopenic and DLB clinical features have dual pathologies, there are rare cases of patients who present with a logopenic PPA phenotype secondary to DLB without evidence of co-existing AD.

Conclusion

LvPPA can be the presenting syndrome of DLB, possibly in the absence of underlying AD pathology. Biomarkers can assist in the diagnosis. Identifying features such as RBD and the cingulate island sign on FDG-PET can be helpful diagnostic clues.

Footnotes

Disclosure of Interest: The authors report no conflict of interest. This study was funded by NIH grants R01-DC010367 and R01-AG050603.

REFERENCES

- Bergeron D, Gorno-Tempini ML, Rabinovici GD, Santos-Santos MA, Seeley W, Miller BL, … Ossenkoppele R (2018). Prevalence of amyloid-beta pathology in distinct variants of primary progressive aphasia. Ann Neurol, 84(5), pp. 729–740. doi:10.1002/ana.25333 Retrieved from 10.1002/ana.25333https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30255971 Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30255971 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caselli RJ, Beach TG, Sue LI, Connor DJ, & Sabbagh MN (2002). Progressive aphasia with Lewy bodies. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord, 14(2), pp. 55–58. doi:10.1159/000064925 Retrieved from 10.1159/000064925https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12145451 Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12145451 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Renzi E, & Vignolo LA (1962). The token test: A sensitive test to detect receptive disturbances in aphasics. Brain, 85, pp. 665–678. doi:10.1093/brain/85.4.665 Retrieved from 10.1093/brain/85.4.665https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/14026018 Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/14026018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukui T, Okita K, Uchiyama M, Kasai H, & Kinno R (2013). Aphasic syndrome in dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB):Is language impairment one of the features of DLB? Journal of the Neurological Sciences, 333 doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2013.07.1177 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Giannini LAA, Irwin DJ, McMillan CT, Ash S, Rascovsky K, Wolk DA, … Grossman M (2017). Clinical marker for Alzheimer disease pathology in logopenic primary progressive aphasia. Neurology, 88(24), pp. 2276–2284. doi:10.1212/WNL.0000000000004034 Retrieved from 10.1212/WNL.0000000000004034https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28515265 Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28515265 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorno-Tempini ML, Brambati SM, Ginex V, Ogar J, Dronkers NF, Marcone A, … Miller BL (2008). The logopenic/phonological variant of primary progressive aphasia. Neurology, 71(16), pp. 1227–1234. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000320506.79811.da [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graff-Radford J, Murray ME, Lowe VJ, Boeve BF, Ferman TJ, Przybelski SA, … Kantarci K (2014). Dementia with Lewy bodies: basis of cingulate island sign. [Research Support, N.I.H., Extramural Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov’t]. Neurology, 83(9), pp. 801–809. doi:10.1212/WNL.0000000000000734 Retrieved from 10.1212/WNL.0000000000000734http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25056580 Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25056580 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jack CR Jr., Bennett DA, Blennow K, Carrillo MC, Dunn B, Haeberlein SB, … Contributors. (2018). NIA-AA Research Framework: Toward a biological definition of Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s & dementia : the journal of the Alzheimer’s Association, 14(4), pp. 535–562. doi:10.1016/j.jalz.2018.02.018 Retrieved from 10.1016/j.jalz.2018.02.018https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29653606 Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29653606 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jack CR Jr., Wiste HJ, Weigand SD, Therneau TM, Lowe VJ, Knopman DS, … Petersen RC (2017). Defining imaging biomarker cut points for brain aging and Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement, 13(3), pp. 205–216. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2016.08.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Josephs KA, Duffy JR, Fossett TR, Strand EA, Claassen DO, Whitwell JL, & Peller PJ (2010). Fluorodeoxyglucose F18 positron emission tomography in progressive apraxia of speech and primary progressive aphasia variants. Arch Neurol, 67(5), pp. 596–605. doi:10.1001/archneurol.2010.78 Retrieved from 10.1001/archneurol.2010.78https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20457960 Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20457960 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Josephs KA, Duffy JR, Strand EA, Machulda MM, Senjem ML, Lowe VJ, … Whitwell JL (2014). APOE epsilon4 influences beta-amyloid deposition in primary progressive aphasia and speech apraxia. Alzheimers Dement, 10(6), pp. 630–636. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2014.03.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Josephs KA, Duffy JR, Strand EA, Machulda MM, Vemuri P, Senjem ML, … Whitwell JL (2014). Progranulin-associated PiB-negative logopenic primary progressive aphasia. J Neurol, 261(3), pp. 604–614. doi:10.1007/s00415-014-7243-9 Retrieved from 10.1007/s00415-014-7243-9https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24449064 Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24449064 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kantarci K, Lowe VJ, Boeve BF, Weigand SD, Senjem ML, Przybelski SA, … Jack CR Jr. (2012). Multimodality imaging characteristics of dementia with Lewy bodies. Neurobiol Aging, 33(9), pp. 2091–2105. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2011.09.024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lansing AE, Ivnik RJ, Cullum CM, & Randolph C (1999). An empirically derived short form of the Boston naming test. Arch Clin Neuropsychol, 14(6), pp. 481–487. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall CR, Hardy CJD, Volkmer A, Russell LL, Bond RL, Fletcher PD, … Warren JD (2018). Primary progressive aphasia: a clinical approach. Journal of neurology, 265(6), pp. 1474–1490. doi:10.1007/s00415-018-8762-6 Retrieved from 10.1007/s00415-018-8762-6https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29392464 Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29392464 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKeith IG, Boeve BF, Dickson DW, Halliday G, Taylor JP, Weintraub D, … Kosaka K (2017). Diagnosis and management of dementia with Lewy bodies: Fourth consensus report of the DLB Consortium. Neurology, 89(1), pp. 88–100. doi: 10.1212/wnl.0000000000004058 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mesulam MM, Weintraub S, Rogalski EJ, Wieneke C, Geula C, & Bigio EH (2014). Asymmetry and heterogeneity of Alzheimer’s and frontotemporal pathology in primary progressive aphasia. Brain, 137(Pt 4), pp. 1176–1192. doi:10.1093/brain/awu024 Retrieved from 10.1093/brain/awu024https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24574501 Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24574501 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riancho J, Pozueta A, Santos M, Lage C, Carril JM, Banzo I, … Sanchez-Juan P (2017). Logopenic Aphasia due to a Strategic Stroke: New Evidence from a Single Case. J Alzheimers Dis, 57(3), pp. 717–721. doi:10.3233/JAD-161267 Retrieved from 10.3233/JAD-161267https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28304307 Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28304307 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rohrer JD, Crutch SJ, Warrington EK, & Warren JD (2010). Progranulin-associated primary progressive aphasia: a distinct phenotype? Neuropsychologia, 48(1), pp. 288–297. doi:10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2009.09.017 Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19766663 ; 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2009.09.017https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19766663https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2808475/ Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19766663 ; https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2808475/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shewan CM, & Kertesz A (1980). Reliability and validity characteristics of the Western Aphasia Battery (WAB). J Speech Hear Disord, 45(3), pp. 308–324. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/7412225 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spinelli EG, Mandelli ML, Miller ZA, Santos-Santos MA, Wilson SM, Agosta F, … Gorno-Tempini ML (2017). Typical and atypical pathology in primary progressive aphasia variants. Ann Neurol, 81(3), pp. 430–443. doi:10.1002/ana.24885 Retrieved from 10.1002/ana.24885https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28133816 Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28133816 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teichmann M, Migliaccio R, Kas A, & Dubois B (2013). Logopenic progressive aphasia beyond Alzheimer’s--an evolution towards dementia with Lewy bodies. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry, 84(1), pp. 113–114. doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2012-302638 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitwell JL, Graff-Radford J, Singh TD, Drubach DA, Senjem ML, Spychalla AJ, … Josephs KA (2017). (18)F-FDG PET in Posterior Cortical Atrophy and Dementia with Lewy Bodies. J Nucl Med, 58(4), pp. 632–638. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.116.179903 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]