Abstract

Rationale

There is a growing concern over excessive caffeine use and development of caffeine use disorder in children.

Objectives

This study aimed to identify the association between caffeine intake and cognitive functioning in children.

Methods

This study included 11718 youths aged 9–10 years with cognitive and caffeine intake information that were extracted from the Adolescent Brain Cognitive Development (ABCD) Study. The ABCD study is a longitudinal cohort study started in 2017 that aims to understand the relationships between substance use and neurocognition in youths living in the United States. Cognitive measures were obtained through the 7 core cognitive instruments from the NIH toolbox (vocabulary comprehension, reading decoding, inhibitory control, working memory, cognitive flexibility, processing speed, and episodic memory). Associations between caffeine intake and the seven cognitive functions were examined using multiple regression models.

Results

Our study revealed that caffeine intake negatively correlated with all the seven cognitive measures. After adjustment for age, gender, sleep, and socio-economic status (SES), caffeine intake was still found to be negatively associated with most of the cognitive functions, such as vocabulary comprehension, working memory, cognitive flexibility, processing speed, and episodic memory, except reading decoding and inhibitory control.

Conclusions

As beverages with caffeine are consumed frequently, controlling their intake may reduce a risk for nonoptimal cognitive development in children.

Keywords: caffeine, cognition, children, executive function

Introduction

Caffeine is one of major components in the most commonly consumed beverages, such as tea, energy drinks, and soda, in the world (Higdon and Frei 2006). Globally, a large number of children consume caffeine on a day-to-day basis with a daily consumption level of 37.3mg/day (U.S), 26.7mg/day (Canada), 20mg/day (New Zealand), 19.2mg/day (Australia) and 23.25mg/day (Branum et al. 2014). Soda is the primary source (38%) of caffeine for children (aged 2–13 years) (Verster and Koenig 2018). Although according to some health regulatory bodies, such as Health Canada, the consumption of caflciiie by adults less than 400mg daily does not present any health risks and may provide certain benefits such as improved concentration, alertness, or even athletic performance, higher doses may instead result A adverse impacts on the consumer's mood, sleep, physical and cognitive performances (McLellan et al. 2016). This is particularly concerning in children as they may be more vulnerable to any adverse effects of caffeine that might exist (Higdon and Frei 2006). There is a growing concern over excessive caffeine use and development of caffeine use disorder in children (Cotter et al. 2013; Budney and Emond 2014). But it is little known about influences of caffeine on child cognitive development.

There is a general agreement in the scientific community regarding specific acute effects of caffeine on cognitive function, such as improved alertness, reaction time and vigilance. However, inconsistencies are still present amongst studies regarding the effects on higher cognitive functions, such as working memory, long-term memory, executive functions, and other higher-order cognitive functions (McLellan et al. 2016). Even though studies have been conducted in this area, targets were mostly adults or the elderly instead of younger populations (Temple 2009). In cases where research was conducted on younger populations, they were usually animal studies or those with a small sample size (O’Neill et al. 2016; Atik et al. 2017).

Caffeine (1,3,7-trimethylxanthine) is structurally similar to one neurotransmitter, adenosine, that regulates neurotransmitter release by interfering with calcium ions and serves to inhibit or reduce neuronal activity (Ribeiro and Sebastio 2010). Once ingested and absorbed into the bloodstream from the gastrointestinal tract, caffeine blocks adenosine receptors in the brain and acts as antagonists to adenosine. Neural firing then becomes less inhibited, causing physiological effects such as increased heart rate, blood pressure, and vasodilation. Additionally, it may also trigger specific effects on cognitive functions such as alertness, memory, attention, and learning, etc (Smit and Rogers 2000). These effects peak around 30–60 minutes after ingestion when caffeine concentration in plasma reaches maximum (Lorist and Snel 2008). Eventually, caffeine gets eliminated from the body system with a half-life of approximately 5–7 hours depending on individual (Tarrus et al. 1987).

Chronic arousal caused by alterations in adenosine signaling from habitual and excessive caffeine consumption has shown to affect not only sleep duration and quality but also neuronal plasticity and brain developmental processes, such as synaptic pruning and myelination (Olini et al. 2013). This is an important concern during the phase of childhood as sleep plays a crucial role in their brain development (Aepli et al. 2015). Moreover, during this phase of growth, the brain is plastic with considerable changes in neuronal circuitry and very prone to environmental influences. Hence, we hypothesize that caffeine intake may result in unexpected effects on cognitive functioning in children. In this study, we took an advantage on the public available data from the ongoing Adolescent Brain Cognitive Development (ABCD) study. We aimed to primarily investigate the relationship between caffeine intake (not psychoactive substances) and cognitive function in children aged 9–10 years. Our findings provide several future avenues for developing new intervention approaches of cognitive improvement.

Methods

Participants

We used data from the ongoing Adolescent Brain Cognitive Development (ABCD) study (data release 2.0; https://abcdstudy.org/). Youths (n = 11,875) aged 9–10 years consisting of a similar proportion of males and females living in the United States were recruited (Volkow et al. 2018). The sample selection criteria were targeted to reflect the sociodemographic proportion of the U.S population as described in the ABCD study design (Garavan et al. 2018). All participants were administered assessments to obtain data on the respective youth's brain morphology, cognitive function, substance use, demographics, and environment (Barch et al. 2018). All parents provided written informed consent, and all children provided assent to a research protocol approved by the institutional review board at each data collection site (https://abcdstudy.org/study-sites/).

Of the 11875 participants, 6 did not report caffeine intake information, 144 did not complete any task of the cognitive battery (i.e., NIH Toolbox), and 7 did not have both of these two data. Therefore, our study included 11718 children who reported the caffeine intake information and underwent the cognitive battery (Lisdahl et al. 2018; Luciana et al. 2018).

Caffeine Intake

The ABCD Substance Use module was administered to the youth by a trainer using an iPad. Youth reported caffeine use via modified Supplemental Beverage Questions which were widely used and have been validated in terms of high correlation with caffeine concentration biomarkers in urine (Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center 2004; Schliep et al. 2013; Vanderlee et al. 2018). Total 5 types of caffeinated drinks, such as coffee, espresso, tea, soda, and energy drinks, were included. The typical serving size of each type of drinks was defined as follows: 1 cup (8 oz) for coffee; 1 shot for espresso; 1 cup (8 oz) for tea; 1 can (12 oz) for soda; 1 cup (2 oz for the drink 5-hr energy; 8 oz for other energy drinks such as Red Bull ) for energy drinks. Each type was asked in the same fashion described below. For example, “typically, how many drinks of the following beverages did you have per week in the past 6 months? coffee (instant, brewed), with caffeine, including flavored types)”. According to the youth’s response, the interviewer determined how many typical cups of caffeine drinks per week in the past 6 months. If the youth drinks less than weekly, then the drink amount was coded as the fraction representing weekly use. For example, if someone had 1 cup of coffee per month, it would be 1/4=0.25 cup per week because there are 4 weeks in one month. Estimated caffeine content for each type of drink was obtained by averaging the caffeine content of all items under each beverage category in the database according to D.C Mitchell et al (Mitchell et al. 2014). Similar to the study on caffeine use in soldiers by McLellan et al., caffeine intake per week was calculated by multiplying the number of cups of each type of drink reported with their estimated caffeine content (McLellan et al. 2018). Caffeine intake per week was then converted to caffeine intake per day (mg/day).

Cognition

This study selected 7 cognitive instruments from the NIH toolbox (http://www.nihtoolbox.org). According to the structure of this toolbox, we obtained two domains of cognitive functions (Akshoomoff et al. 2014), crystallized and fluid cognitive domains. Crystallized cognitive battery includes picture vocabulary (vocabulary comprehension) and oral reading recognition tasks (reading decoding). Fluid cognitive battery includes flanker (inhibitory control), dimensional change card sort (cognitive flexibility), list sorting working memory (working memory), picture sequence memory (episodic memory), and pattern comparison processing speed tasks (processing speed) (Luciana et al. 2018). These measures were selected as they were proven to be psychometrically sound and provided reliable evaluations of cognitive functioning for the current age group of interest (Luciana et al. 2018). The scoring method for the NIH toolbox cognitive instruments can be found in the overview of the NIH cognition battery and NIH Scoring and Interpretation guide (Weintraub et al. 2013; Luciana et al. 2018).

On the day of cognitive assessment, the Participant Last Use Survey (PLUS) was administered to children to report whether they had taken any caffeine within the last 24h. We used this measure to examine chronic effects of caffeine on cognition.

Socioeconomic Status (SES) and Sleep

SES factors, such as income, education, parental care and presence of a sufficiently cognitive stimulating environment, were previously studied and suggested to exert influences on cognitive abilities, such as executive function, working memory and language (Noble et al. 2015; Farah 2017). A composite SES score was generated by dividing the sum of scores of selected ordinal variables from the maximum possible score. Family income, parental education, family environment, neighborhood safety, and parental behavior were chosen to be included in the composite SES score based on suggestions from previous studies (Christensen et al. 2014).

The Sleep Disturbance Scale for Children (SDSC) was used to measure children’s sleep function. The SDSC is a 26-item Likert-type rating scale administrated to a parent (Bruni et al. 1996). A higher score reflects a greater degree of disturbed sleep. In this study, SES and sleep were used as confounding variables in statistical analysis described below.

Statistical Analysis

Several potential confounders, such as age, gender, sleep, and SES, were included in statistical analysis as they were not only found to be correlated with caffeine intake and cognitive abilities in our study but also identified as covariates in previous association studies related to the effects of caffeine use on cognition (Skinner et al. 2000; Kyle et al. 2010; Lo et al. 2016).

Spearman’s rank-order correlations were used to assess relationships between caffeine, cognition and potential confounding variables (de Winter et al. 2016). Multiple linear regression models were also used to examine the association of caffeine intake with each cognitive function after controlling of potential confounders, such as age, gender, sleep, and SES. Before entering into multiple linear regression, all variables were first normalized through a rank-based inverse Gaussian transformation to avoid potential influences of outlier values and improve the robustness of our findings (Miller et al. 2016). Moreover, we computed the variance inflation factor (VIF) of all confounding variables. The VIF varied from 1.01 to 1.06, suggesting no collinearity problem among the confounding variables (Belsley et al. 1980). All data analysis was conducted using MATLAB (Statistics and Machine Learning Toolbox, Release 2017b). Two-tailed tests with a significance level of p < 0.05 were set for this study.

Results

Demographics

This study included 11,718 participants (age: 9.9 ± 0.6 years), consisting of 52.1% male and 47.9% females (Table 1). Table 1 lists the demographic information of the study sample. The parental highest level of education and annual income were reported during the interview. 51.4% of children had at least one parent who graduated from college or university and 34.1% had at least one parent who completed a Master’s degree or above. Additionally, 53.9% of the participated families received an annual household income of $50,000-$200,000. The range of sleep disturbance scores was 26–126 (mean ± SD=36.5 ± 8.2; median=34, IQR=9).

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics (n = 11718).

| Variable | Mean (Rijlaarsdam et al.) |

| Age | 9.9 (0.6) |

| Sleep | 36.5 (8.2) |

| Variable | Participants no. (%)* |

| Gender | |

| Male | 6104 (52.1) |

| Female | 5611 (47.9) |

| Race/ethnicity | |

| White | 6104 (52.1) |

| Black | 1743 (14.8) |

| Hispanic | 2377 (20.3) |

| Asian | 252 (2.2) |

| Others | 1227 (10.5) |

| Annual Family Income | |

| < $50,000 | 3166 (27.0) |

| $50,000 – $199,999 | 6317 (53.9) |

| > $200,000 | 1232 (10.5) |

| Parent’s Highest Educational Level | |

| Never Completed High School | 581 (5.0) |

| High School Graduate or GED | 1112 (9.5) |

| Some College or Bachelor’s Degree | 6021 (51.4) |

| Master’s Degree or above | 3991 (34.1) |

Due to missing values, the sum of percentages may not equal to 100%.

Caffeine Intake and Cognition

The youth substance use interview reported that 66.9% of the sample consumed at least one type of caffeinated beverages in the past 6 months. Of all subjects who consumed caffeinated drinks, soda was the greatest contributor to their total caffeine intake followed by tea, coffee, espresso, and energy drinks (Table 2). Average caffeine intake is 13.00 ∓ 43.73mg/day (Table 3), which is equivalent to 1/8 of a can of AMP energy drink (12 fl oz) or two packages of M & M's Milk Chocolate Candies according to USDA National Nutrient Database (https://www.nal.usda.gov/sites/www.nal.usda.gov/files/caffeine.pdf). The distribution of caffeine intake amount was skewed with a range from 0 to 1195mg/day and median of 1.76 mg/dav.

Table 2.

Distribution of caffeinated drink consumption and the corresponding demographics (n = 11718).

| Beverages | Participants no. (%) | Age (Mean±SD) | Gender* (Male / Female) | Race/ethnicity* (White / Black / Hispanic / Asian / Others) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No consumption | 3877 (33.1) | 9.8±0.6 | 1867 / 2008 | 2180 / 452 / 756 / 108 / 377 |

| Consume one type | ||||

| Coffee | 178 (1.5) | 9.9±0.6 | 90 / 88 | 81 / 21 / 51 /7 / 18 |

| Espresso | 76 (0.7) | 10.0±0.7 | 30 /46 | 34 / 9 / 21 / 5 / 7 |

| Tea | 642 (5.5) | 9.9±0.6 | 283 /359 | 316 / 117 / 103 / 26 / 79 |

| Soda | 3190 (27.2) | 9.9±0.6 | 1823 /1367 | 1822 / 364 / 661 / 51 / 286 |

| Energy Drinks | 15 (0.1) | 9.9±0.7 | 10 / 5 | 9 / 1 / 3 / 0 / 2 |

| Consume two types | ||||

| Coffee & Tea | 113 (1.0) | 9.9±0.6 | 52 /60 | 53 / 15 / 29 / 5 / 11 |

| Coffee & Soda | 532 (4.5) | 10.0±0.6 | 218 /253 | 218 / 66 /187 / 5 / 56 |

| Espresso & Soda | 231 (2.0) | 10.0±0.6 | 100 /131 | 94 / 18 / 88 / 5 /25 |

| Tea & Soda | 1609 (13.7) | 9.9±0.6 | 891 /718 | 715 / 432 / 229 / 22 / 209 |

| Others | 144 (1.2) | 20.0±0.6 | 81 63 | 63 / 28 /24 /1 /28 |

| Consume three or more types | 1111 (9.5) | 20.0±0.6 | 589 /513 | 519 / 220 / 225/ 17/ 129 |

Due to missing values, the sum of percentages may not equal to 100%.

Table 3.

Caffeine intake and cognitive scores derived from the ABCD Youth Substance Use Interview and the NIH toolbox.

| Mean (Rijlaarsdam et al.) | Median (IQR) | Range | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Caffeine Intake / mg per day | 13.00 (43.73) | 1.76 (9.49) | 0 – 1195 |

| Crystallized Cognitive Skills | |||

| Vocabulary Comprehension | 106.79 (16.99) | 106.00 (22.00) | 0 –208 |

| Reading Decoding | 102.52 (19.12) | 100.00 (20.00) | 64 – 206 |

| Fluid Cognitive Skills | |||

| Inhibitory Control | 95.43 (13.67) | 97.00 (22.00) | 62 – 171 |

| Working Memory | 100.55 (14.78) | 103.00 (21.00) | 39 – 194 |

| Cognitive Flexibility | 96.72 (15.16) | 94.00 (17.00) | 65 – 191 |

| Processing Speed | 93.79 (22.10) | 95.00 (26.00) | 20 – 185 |

| Episodic Memory | 100.96 (16.11) | 99.00 (21.00) | 64 – 172 |

Abbreviations: SD, standard deviation; IQR, interquartile range.

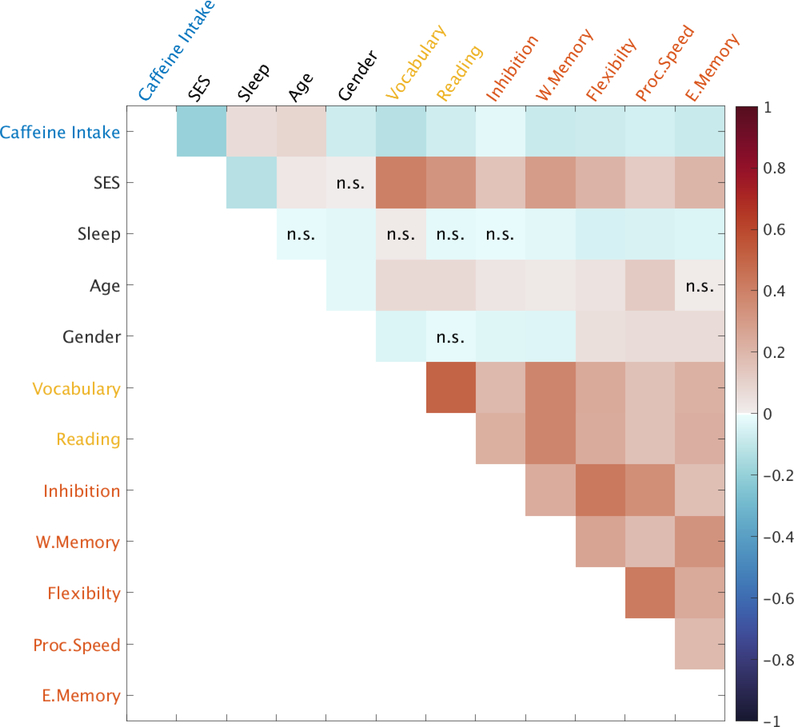

The descriptive statistics for each administered cognitive test can be found in Table 3. Figure 1 illustrates the correlation heat map between caffeine intake and all seven cognitive measures, suggesting significant negative correlations with all crystallized cognitive functions (vocabulary comprehension: ρ = − 0.12, p < 0.01; reading decoding: ρ = −0.07, p < 0.01) and all fluid cognitive functions ( inhibitorycontrol: ρ = −0.02, p = 0.02; working memory: ρ = −0.08, p < 0.01; cognitive flexibility: ρ = −0.07, p < 0.01; processing speed: ρ = −0.06, p < 0.01; episodic memory: ρ = −0.08, p < 0.01). This indicates that increased caffeine intake was associated with decreased crystallized and fluid cognitive abilities. All cognitive functions were positively correlated to each other (min ρ > 0.16, p < 0.01). Lower SES was associated with greater caffeine intake (ρ = −0.19, p < 0.01) and worse cognitive performance (min ρ > 0.12, p < 0.01). Older age children consumed more caffeine (ρ = 0.09, p < 0.01) and had better cognitive functions (min ρ > 0.12, p < 0.01) except the episodic memory (ρ = 0.01, p = 0.12). More sleep disturbances were associated with greater caffeine intake (ρ = 0.06, p < 0.01) and worse performance in most of the seven cognitive functions (max ρ < −0.02, p < 0.01) except the crystallized cognitive functions and inhibitory control. Compared to females, males had higher caffeine consumption (ρ = −0.07, p < 0.01), performed better in vocabulary comprehension, inhibitory control, and working memory (max ρ < −0.03, p < 0.01), but performed worse in the other three fluid cognitive functions (min ρ > 0.05, p < 0.01). Interestingly, better SES was associated with fewer sleep disturbances (ρ = −0.12, p < 0.01), and males showed more sleep disturbances than females (ρ = −0.03, p < 0.01).

Figure 1.

Spearman’s correlation heat map.

Abbreviations: n.s, no significance; Vocabulary, vocabulary comprehension; Reading, reading decoding; Inhibition, inhibitory control; W.Memory, working memory; Flexibility, cognitive flexibility; Proc.Speed, processing speed; E.Memory, episodic memory.

After controlling for age, gender, sleep, and SES, caffeine intake was no longer significantly associated with reading decoding (β = −0.02, p = 0.07) and inhibition control (β = −0.01, p = 0.80). Increased caffeine intake was significantly associated with decreased vocabulary comprehension (β = −0.07, p < 0.01), suggesting with every increase of one standard deviation in caffeine intake, the vocabulary comprehension score decreases by 0.02 standard deviation. Similarly, increased caffeine intake was also significantly associated with decreased working memory (β = −0.04, p < 0.01), cognitive flexibility (β = − 0.04, p < 0.01), processing speed (β = −0.05, p < 0.01), and episodic memory (β = −0.04, p < 0:01). Because the sample was from 21 research sites, our study further added the site ID as a random effect in statistical analysis. The abovementioned findings remained the same.

To avoid potential acute effects of caffeine on cognition, we re-run the analysis and excluded the children who reported caffeine intake in last 24 hours prior to cognitive assessment. This analysis only included 3798 children among 4518 who reported the PLUS measure and revealed the results similar to those in Table 4. In details, increased caffeine intake was significantly associated with decreased vocabulary comprehension (ß = −0.07, p < 0.01), working memory (ß = −0.04, p = 0.04), cognitive flexibility (ß = −0.04, p = 0.03), processing speed (ß = −0.06, p < 0.01), and episodic memory (ß = −0.06, p < 0.01). No significant findings were found in the associations of caffeine intake with reading decoding (ß = −0.01, p = 0.46) and inhibitory control abilities (ß = 0.01, p = 0.65).

Table 4.

Regression coefficients, standardized β, and p-values indicate the relationship between caffeine intake and cognitive functions after controlling for age, gender, sleep, and socioeconomic status.

| Standardized β Value [95% CI] | p-value | df | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Crystallized Cognitive Skills | |||

| Vocabulary Comprehension | −0.07 [−0.09, −0.05] | <.01 | 10587 |

| Reading Decoding | −0.02 [−0.04, 0.01] | 0.07 | 10576 |

| Fluid Cognitive Skills | |||

| Inhibitory Control | −0.01 [−0.02, 0.02] | 0.80 | 10582 |

| Working Memory | −0.04 [−0.06, −0.02] | <.01 | 10548 |

| Cognitive Flexibility | −0.04 [−0.06, −0.02] | <.01 | 10583 |

| Processing Speed | −0.05 [−0.07, −0.03] | <.01 | 10567 |

| Episodic Memory | −0.04 [−0.06, −0.02] | <.01 | 10577 |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; df, degrees of freedom.

Discussion

The results obtained from this study indicated that increasing caffeine intake was associated with lower scores in several cognitive functions, such as vocabulary comprehension, working memory, cognitive flexibility, processing speed, and episodic memory in children.

Previous literature suggested that caffeine at a certain level may benefit cognitive function, such as executive function and processing speed (Heatherley et al. 2006; Hunt et al. 2011; Soar et al. 2016), which is inconsistent with our findings. Notably, most of existing studies were based on a randomized double-blind, placebo-controlled design and found the acute effect of caffeine on cognition (Castellanos and Rapoport 2002). In contrast, our study was a population-based study. We revealed adverse influence of caffeine intake on youth's cognitive function. When excluding children with caffeine intake in last 24 hours prior to cognitive assessment, we still observed the adverse influence of caffeine intake on cognition. Even we controlled for psychopathology in our analysis, such as ADHD that was often observed in children, the negative association between caffeine intake and cognition remained the same (see the Supplementary Material). Similar to the current study, one of recent studies asked adolescents to report their consumption of caffeine drinks during a week of time, and found the negative correlation between executive functions and caffeine intake (Van Batenburg-Eddes et al. 2014).

Our study focused specifically on children aged 9–10 years, during which the brain maturation that has a large impact on a variety of cognitive functions (Casey et al. 2000). Our findings suggest that children who consume more caffeine on a regular basis perform worse in cognition. Although the effects of caffeine intake on youth's brain development have not yet been examined, caffeine may alter normal brain development during critical developmental periods. This stems from the evidence that the animal model of perinatal caffeine exposure had long-lasting effects on brain function (Temple 2009). Moreover, the tendency of more caffeine intake in childhood may increase the risk of habitual and even excessive caffeine consumption later in life. This could cause chronic arousal and sleep problems, and affect neuronal plasticity and brain developmental processes, such as synaptic pruning and myelination (Olini et al. 2013).

Despite some studies reported that of the habitual caffeine use improves motor speed (Van Boxtel et al. 2003), further study should be conducted on the effects of caffeine intake on cognitive processes during tasks that require less motor-weighted components, particular in children (Nehlig 2010). Moreover, past studies have never shown any relationship between caffeine intake and crystallized abilities such as language. Thus, more investigation should be carried out to confirm our results where oral reading and vocabulary comprehension scores decreased significantly with increasing caffeine intake, suggesting that improper amount of caffeine intake may negatively affect crystallized cognitive functions.

The strengths of this study include the large sample size of young subjects and administration of reliable cognitive performance measures. However, there are some limitations of the present analysis that have to be considered. Firstly, most measures were either self or parent-reported which may result in discrepancies for caffeine intake measure. Secondly, the study would have benefited from the inclusion of more high-caffeine consumers to generate a more balanced distribution of caffeine. Last but not least, it has been shown that sugar consumption during childhood may adversely impact child cognition (Cohen et al. 2018). Hence, there could be confounding effects on cognitive functions due to sugar content of caffeinated beverages. Unfortunately, the sugar intake was not a major focus of the ABCD study and hence was not assessed. Future investigation is needed to parse out which sugar and caffeine intakes contribute most to cognitive development in children.

Although further study is required on the complex pharmacologic and neural mechanisms of caffeine intake to understand its effects on each specific cognitive function, the results from this study suggest a negative impact by caffeine on cognitive development in children. This is especially important today where a large number of children consume beverages with caffeine regularly. Thus, from a public health perspective, we advise parents to control their children’s intake of beverages with caffeine to reduce the risk of interference with normal cognitive development

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Data used in the preparation of this article were obtained from the Adolescent Brain Cognitive Development (ABCD) Study (https://abcdstudy.org), held in the NIMH Data Archive. This is a multisite, longitudinal study designed to recruit more than 10,000 children age 9–10 and follow them over 10 years into early adulthood. The ABCD Study is supported by the National Institutes of Health and additional federal partners under award numbers U01DA041022, U01DA041028, U01DA041048, U01DA041089, U01DA041106, U01DA041117, U01DA041120, U01DA041134, U01DA041148, U01DA041156, U01DA041174, U24DA041123, and U24DA041147. A full list of supporters is available at https://abcdstudy.org/study-sites/. A listing of participating sites and a complete listing of the study investigators can be found at https://abcdstudy.org/Consortium_Members.pdf. ABCD consortium investigators designed and implemented the study and/or provided data but did not necessarily participate in analysis or writing of this report. This manuscript reflects the views of the authors and may not reflect the opinions or views of the NIH or ABCD consortium investigators. The ABCD data repository grows and changes over time. The ABCD data used in this report came from DOI: 10.15154/1503209.

This research is also supported by Singapore Ministry of Education (Academic research fund tier 1; NUHSRO/2017/052/T1-SRP-Partnership/01), and NUS Institute of Data Science, Singapore.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest relevant to this article to disclose.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This Author Accepted Manuscript is a PDF file of a an unedited peer-reviewed manuscript that has been accepted for publication but has not been copyedited or corrected. The official version of record that is published in the journal is kept up to date and so may therefore differ from this version.

References

- Aepli A, Kurth S, Tesler N, et al. (2015) Caffeine Consuming Children and Adolescents Show Altered Sleep Behavior and Deep Sleep. Brain Sci 5:441–455. 10.3390/brainsci5040441 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akshoomoff N, Newman E, Thompson WK, et al. (2014) The NIH Toolbox Cognition Battery: Results from a large normative developmental sample (PING). Neuropsychology 28:1–10. 10.1037/neu0000001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atik A, Harding R, De Matteo R, et al. (2017) Caffeine for apnea of prematurity: Effects on the developing brain. Neurotoxicology 58:94–102. https://doi.Org/10.1016/j.neuro.2016.11.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barch DM, Albaugh MD, Avenevoli S, et al. (2018) Demographic, physical and mental health assessments in die adolescent brain and cognitive development study: Rationale and description. Dev Cogn Neurosci 32:55–66. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dcn.2017.10.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belsley DA, Kuh E, Welsch RE (1980) Regression diagnostics: Identifying influential observations and sources of collinearity. John Wiley Sons [Google Scholar]

- Branum AM, Rossen LM, Schoendorf KC (2014) Trends in Caffeine Intake Among US Children and Adolescents. Pediatrics 133:386–393. 10.1542/peds.2013-2877 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruni O, Ottaviano S, Guidetti V, et al. (1996) The Sleep Disturbance Scale for Children (SDSC) Construct ion and validation of an instrument to evaluate sleep disturbances in childhood and adolescence. J Sleep Res 5:251–261. https://doi.Org/10.1111/j.1365-2869.1996.00251.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Budney AJ, Emond JA (2014) Caffeine addiction? Caffeine for youth? Time to act! Addiction 109:1771–1772.. 10.1111/add.12594 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casey BJ, Giedd JN, Thomas KM (2000) Structural and functional brain development and its relation to cognitive development. Biol Psychol 54:241–257. 10.1016/S0301-0511(00)00058-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castellanos FX, Rapoport JL (2002) Effects of caffeine on development and behavior in infancy and childhood: A review of the published literature. Food Chem. Toxicol. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Christensen DL, Schieve LA, Devine O, Drews-Botsch C (2014) Socioeconomic status, child enrichment factors, and cognitive performance among preschool-age children: Results from the Follow-Up of Growth and Development Experiences study. Res Dev Disabil 35:1789–1801. 10.1016/j.ridd.2014.02.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen JFW, Rifas-Shiman SL, Young J, Oken E (2018) Associations of Prenatal and Child Sugar Intake With Child Cognition. Am J Prev Med. 10.1016/j.amepre.2018.02.020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cotter BV., Jackson DAE, Merchant RC, et al. (2013) Energy drink and other substanance use among adolescent and young adult emergency department patients. Pediatr Emerg Care 10.1097/PEC.0b013e3182a6403d [DOI] [PubMed]

- de Winter JCF, Gosling SD, Potter J (2016) Comparing the pearson and spearman correlation coefficients across distributions and sample sizes: A tutorial using simulations and Empirical data. Psychol Methods 21:273–290. 10.1037/met0000079 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farah MJ (2017) The neuroscience of socioeconomic status: correlates, causes, and consequences. Neuron 96:56–71. 10.1016/j.neuron.2017.08.034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center (2004) Caffeine questionnaire. In: Seattle, WA: Fred Hutchinson Cancer Res. Cent, https://sharedresources.fredhutch.org/d6cuments/caffeine-questionnaire [Google Scholar]

- Garavan H, Bartsch H, Conway K, et al. (2018) Recruiting the ABCD sample: Design considerations and procedures. Dev Cogn Neurosci 32:16–22. 10.1016/j-dcn.2018.04.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heatherley SV., Hancock KMF, Rogers PJ (2006) Psychostimulant and other effects of caffeine in 9- to 11-year-old children. J Child Psychol Psychiatry Allied Discip https://doi.org/10.llll/j-1469-7610.2005.01457.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higdon JV., Frei B (2006) Coffee and Health: A Review of Recent Human Research. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr 46:101–123. 10.1080/10408390500400009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunt MG, Momjian AJ, Wong KK (2011) Effects of diurnal variation and caffeine consumption on Test of Variables of Attention (TOVA) performance in healthy young adults. Psychol Assess 23:226–233. https://doi.org/10.jft37/aOO214Ol [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kyle J, Fox HG, Whalley LJ (2010) Caffeine, cognition, and socioeconomic status. J Alzheimer’s Dis 2(1151–159. 10.3233/JAD-2010-1409 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lisdahl KVQ Sher KJ, Conway KP, et al. (2018) Adolescent brain cognitive development (ABCD) study: Overview of substance use assessment methods. Dev Cogn Neurosci 32:80–96. 10.1016/j.dcn.2018.02.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lo JC, Ong JL, Leong RLF, et al. (2016) Cognitive Performance, Sleepiness, and Mood in Partially Sleep Deprived Adolescents: The Need for Sleep Study. Sleep 39:687–698. https://doi. org/10.5665/sleep.5552 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorist MM, Snel J (2008) Caffeine, Sleep, and Quality of Life. In: Sleep and Quality of Life in Clinical Medicine Humana Press, Totowa, NJ, pp 325–332 [Google Scholar]

- Luciana M, Bjork JM, Nagel BJ, et al. (2018) Adolescent neurocognitive development and impacts of substance use: Overview of the adolescent brain cognitive development (ABCD) baseline neurocognition battery. Dev Cogn Neurosci 32:67–79. 10.1016/j.dcn.2018.02.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLellan TM, Caldwell JA, Lieberman HR (2016) A review of caffeine’s effects on cognitive, physical and occupational performance. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 71:294–312. 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2016.09.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLellan TM, Riviere LA, Williams KW, et al. (2018) Caffeine and energy drink use by combat arms soldiers in Afghanistan as a countermeasure for sleep loss and high operational demands. Nutr Neurosci 0:1–10. 10.1080/1028415X.2018.1443996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller KL, Alfaro-Almagro F, Bangerter NK, et al. (2016) Multimodal population brain imaging in the UK Biobank prospective epidemiological study. Nat Neurosci 19:1523–1536. 10.1038/nn.4393 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell DC, Knight CA, Hockenberry J, et al. (2014) Beverage caffeine intakes in the U.S. Food Chem Toxicol 63:136–142. 10.1016/j.fct.2013.10.042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nehlig A (2010) Is caffeine a cognitive enhancer? J Alzheimer’s Dis 20:. 10.3233/JAD-2010-091315 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noble KG, Houston SM, Brito NH, et al. (2015) Family income, parental education and brain structure in children and adolescents. Nat Neurosci 18:773–8. 10.1038/nn.3983 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Neill CE, Newsom RJ, Stafford J, et al. (2016) Adolescent caffeine consumption increases adulthood anxiety-related behavior and modifies neuroendocrine signaling. Psychoneuroendocrinology 67:40–50. 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2016.01.030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olini N, Kurth S, Huber R (2013) The Effects of Caffeine on Sleep and Maturational Markers in the Rat. PLoS One 8:1–8. 10.1371/journal.pone.0072539 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ribeiro JA, Sebastio AM (2010) Caffeine and adenosine. J Alzheimer’s Dis 20:. 10.3233/JAD-2010-1379 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schliep KC, Schisterman EF, Mumford SL, et al. (2013) Validation of different instruments for caffeine measurement among premenopausal women in the BioCycle Study. Am J Epidemiol 177:690–699. 10.1093/aje/kws283 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skinner JD, Carruth BR, Houck KS, et al. (2000) Caffeine Intake in Young Children Differs by Family Socioeconomic Status. J Am Diet Assoc 100:229–231. 10.1016/S0002-8223(00)00069-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smit HJ, Rogers PJ (2000) Effects of low doses of caffeine on cognitive performance, mood and thirst in low and higher caffeine consumers. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 152:167–73. 10.1007/s002130000506 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soar K, Chapman E, Lavan N, et al. (2016) Investigating the effects of caffeine on executive functions using traditional Stroop and a new ecologically-valid virtual reality task, the Jansari assessment of Executive Functions (JEF © ). Appetite 105:156–163. 10.1016/j.appet.2016.05.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tarrus E, Cami J, Roberts D, et al. (1987) Accumulation of caffeine in healthy volunteers treated with furafylline. Br J Clin Pharmacol 23:9–18. 10.1111/j.1365-2125.1987.tb03003.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Temple JL (2009) Caffeine use in children: What we know, what we have left to learn, and why we should worry. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 33:793–806. 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2009.01.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Batenburg-Eddes T, Lee NC, Weeda WD, et al. (2014) The potential adverse effect of energy drinks on executive functions in early adolescence. Front Psychol 10.3389/fpsyg.2014.00457 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Boxtel MPJ, Schmitt JAJ, Bosma H, Jolles J (2003) The effects of habitual caffeine use on cognitive change: A longitudinal perspective. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 75:921–927. 10.1016/S0091-3057(03)00171-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanderlee L, Reid JL, White CM, et al. (2018) Evaluation of a 24-Hour Caffeine Intake Assessment Compared with Urinary Biomarkers of Caffeine Intake among Young Adults in Canada. J Acad Nutr Diet 118:2245–2253.e1. 10.1016/j.jand.2018.07.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verster JC, Koenig J (2018) Caffeine intake and its sources: A review of national representative studies. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr 58:1250–1259. 10.1080/10408398.2016.1247252 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volkow ND, Koob GF, Croyle RT, et al. (2018) The conception of the ABCD study: From substance use to a broad NIH collaboration. Dev Cogn Neurosci 32:4–7. 10.1016/j.dcn.2017.10.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weintraub S, Dikmen SS, Heaton RK, et al. (2013) Cognition assessment using the NIH Toolbox. Neurology 80:S54–S64. 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3182872ded [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.