Abstract

GRP78, a major molecular chaperone, is critical for the folding and maturation of membrane and secretory proteins and serves as the master regulator of the unfolded protein response. Thus, GRP78 is frequently upregulated in highly proliferative cells to cope with elevated protein synthesis and metabolic stress. IGF-1 is a potent regulator of cell growth, metabolism and survival. Previously we discovered that GRP78 is a novel downstream target of IGF-1 signaling by utilizing mouse embryonic fibroblast model systems where the IGF-1 receptor (IGF-1R) was either overexpressed (R+) or knockout (R−). Here we investigated the mechanisms whereby GRP78 is upregulated in the R+ cells. Our studies revealed that suppression of PI3K/AKT/mTOR downstream of IGF-1R signaling resulted in concurrent decrease in GRP78 and the transcription factor ATF4. Through knock-down and overexpression studies, we established ATF4 as the essential downstream nodal of the PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling pathway critical for GRP78 transcriptional upregulation mediated by IGF-1R.

Keywords: IGF-1, GRP78, ATF4, PI3K/AKT/mTOR, growth factor signaling

Introduction

The 78-kDa glucose-regulated protein (GRP78), also known as BiP or HSPA5, is a major molecular chaperone residing in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) that plays a critical role in folding and processing of nascent membrane bound or secretory proteins and serves as the master regulator of the unfolded protein response (UPR) (Lee, 2014; B. Luo & Lee, 2013; Ni & Lee, 2007). When the folding capacity of the ER is overwhelmed with excessive accumulation of malfolded protein, the cell undergoes ER stress and activates the UPR which is a complex and intricate signaling network designed to help the cell cope with this proteotoxic stress by suppressing global protein synthesis as well as upregulating ER chaperones such as GRP78 and GRP94 to augment the ER homeostasis (Diehl et al., 2011; Lee, 2014; B. Luo & Lee, 2013). UPR activation and GRP78 overexpression are frequently reported in cancers where there is rapid cell growth and proliferation resulting in ER protein overload (Lebeaupin et al., 2020; Lee, 2014; Shen et al., 2017). In addition to cancer, GRP78 maintains organ homeostasis and is particularly important during embryonic development in which knock-out of GRP78 in the mouse embryo resulted in the loss of cell proliferation and early embryonic lethality (S. Luo et al., 2006; Zhu & Lee, 2015). While the UPR and GRP78 have been extensively studied in the context of pathological or pharmacological stresses in various diseases and their treatment (Booth et al., 2015; Casas, 2017; Cook & Clarke, 2015; Lee, 2014; Roller & Maddalo, 2013; Ye et al., 2010), less is known about how GRP78 is regulated under natural physiological process upon hormone and growth factor stimulation during normal development.

The insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1) is an important growth and proliferation signal throughout vertebrates development (Cohen, 2006; Hakuno & Takahashi, 2018). Stimulation of the cell surface IGF-1 receptor (IGF-1R) upon ligand binding leads to dimerization, autophosphorylation of the receptor and activation of downstream signaling cascades such as the mitogen activation protein kinase (MAPK) and phosphatidylinosital-3-kinase (PI3K) pathways which are the two major pro-survival and pro-growth signaling pathways in the cell (Cohen, 2006; Hakuno & Takahashi, 2018). Since all membrane and secretory proteins are processed in the ER, cellular proliferation induced by growth factor signaling could be coupled to chaperone expression to enhance the ER folding capacity. Previously we have uncovered a novel relationship between IGF-1 signaling and GRP78 expression. Utilizing mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) with IGF-1R overexpression (R+) or knock-out (R−), we observed a dramatic reduction of GRP78 protein and mRNA levels in the R− cells and an elevated GRP78 expression in the R+ cells (Pfaffenbach et al., 2012). This suggests that GRP78 is a novel target for IGF-1R mediated signaling. Further investigation revealed that the loss of GRP78 expression in the R− cells is independent of the UPR or the FOXO1 transcription factor. Interestingly, the R− cells exhibit a near complete depletion of phosphorylated AKT while the level of ERK1/2 phosphorylation is comparable to that of the R+ cells which show robust amount of phospho-AKT (pAKT) (Pfaffenbach et al., 2012). These observations suggest that IGF-1R regulation of GPR78 is likely mediated through the PI3K/AKT/mTOR axis of the IGF-1 pathway and not the MAPK/ERK branch. However, the precise molecular factor linking IGF-1R to stimulation of GRP78 expression remains to be determined.

The activating transcription factor 4 (ATF4), also known as cAMP-response element binding protein 2 (CREB2), belongs to the activating transcription factor family which all shares a basic-region leucine zipper (bZIP) motif required for DNA binding activity (Hai & Hartman, 2001). ATF4 acts as a master transcription factor in the integrated stress response (ISR) which includes ER stress (Pakos-Zebrucka et al., 2016). ATF4 is frequently upregulated in cancers and has emerged as a critical factor for tumor survival and progression (Pathria et al., 2019; Singleton & Harris, 2012; Staschke & Wek, 2019; Tameire et al., 2019). We have previously reported that the Grp78 promoter contains a cAMP-response element (CRE) sequence upstream of the ER stress-response element (ERSE) sequences and ATF4 is capable of binding to this CRE site to activate transcription (Alexandra et al., 1991; S. Luo et al., 2003). In this study, using a combination of biochemical and molecular approaches, we identified ATF4 as a downstream nodal of the PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling pathway critical for GRP78 expression mediated by IGF-1R.

Materials and Methods

Cell Culture

MEFs with IGF-1R overexpression (R+) or knock-out (R−) were obtained courtesy of Renato Baserga (Thomas Jefferson University; Drakas et al., 2004; Sell et al., 1993). Wild-type mouse embryonic fibroblast (MEF) was obtained courtesy of Stanley Korsmeyer (Harvard University; Ye et al., 2010). All cells were cultured under normal growth condition using Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM with 4.5g/L glucose) supplemented with 10% Fetal Bovine Serum (FBS) and 1% Penicillin/Streptomycin at 37°C and 5% CO2. For IGF-1 or serum stimulation experiment, MEFs were cultured in DMEM 4.5g/L glucose supplemented with 1% Penicillin/Streptomycin at 37°C and 5% CO2 for 48 hr before recombinant human IGF-1 (R&D Systems, Inc.) or serum stimulation. For chemical inhibition of the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway, the specific PI3K inhibitor LY294002 (50μM; Cell Signaling), the specific AKT inhibitor MK2206 (1μM, Selleck Chemicals), and the specific mTOR inhibitor Rapamycin (20nM, Selleck Chemicals) were added to DMEM 10% FBS 1% Pen/Strep with DMSO serving as vehicle control and incubated for 24 hr.

Experiments with forced overexpression of ATF4 were done in R− and MEFs transfected for 48 hr with pcDNA3 empty vector or vector carrying the full-length wild-type ATF4 gene (Gift from Yihong Ye, Addgene Plasmid# 26114) using BioT transfection reagent according to manufacturer’s recommendation (Bioland Scientific, Paramount, CA). For shRNA knock-down of ATF4, R+ cells were transduced with lentivirus expressing short hairpin RNA specifically targeting mouse ATF4 (shATF4#1: TGCTGCTTACATTACTCTAAT, shATF4#2: GCGAGTGTAAGGAGCTAGAAA) or control shRNA (shCtr: AGGTTAAGTCGCCCTCG) using Polybrene (8μg/ml). After 48 hr, transduced cells were selected with Puromycin (4μg/ml) for 7 days to establish permanent cell lines expressing the shRNA constructs.

Cloning and production of lentivirus in 293T cells

pLKO.1 lentiviral vector was double digested with AgeI and EcoRI (New England BioLabs) and gel purified by ZymoClean Gel DNA Recovery Kit (Zymo Research, Irvine, CA). DNA oligos containing the targeting sequence against ATF4 or scramble control sequence were synthesized by Integrated DNA Technologies (Coralville, IA) and annealed in NEB Buffer 2. Annealed DNA oligos were ligated into cut and purified pLKO.1 vector which was then co-transfected into 293T cells along with pMD2.G and pCMVΔR8.2 packaging plasmids using BioT transfection reagent. Next day, the media was removed, and fresh media was added to allow for virus production for the next 48 hr. Viral particles secreted into the growth media were harvested, spun down to remove cellular debris and filtered through a 0.45μM filter. Virus particles were then concentrated from the media by using the PEG-it Virus Precipitation solution (System Biosciences, Palo Alto, CA) and resuspended in 1ml of sterile PBS.

RNA extraction and Reverse Transcription PCR

Total RNA was extracted from 6cm dishes using 1ml of TRI reagent (Millipore-Sigma) according to manufacturer’s recommendation. Complementary DNA was synthesized from 1μg of total RNA using SuperScript II Reverse Transcriptase (ThermoFisher, Waltham, MA) following manufacturer’s instruction. For detection of Grp78, Atf4, and β-actin, 1μL of cDNA was used in PCR with the following conditions (25 cycles, 30s at 95°C, 30s at 60°C, 45s at 72°C). The PCR products were resolved in 1% agarose gel and visualized by ChemiDoc XRS+ Imager (Bio-Rad Laboratories). The primers for Grp78 are 5’-ACTTCAATGATGCCCAGCGA-3’ and 5’-AGCCTTTTCTACCTCACGCC-3’, Atf4 are 5’-TGACCTGGAAACCATGCCAG-3’ and 5’-AATGCTCTGGAGTGGAAGAC-3’, β-actin are 5’-TACCACAGGCATTGTGATGG-3’ and 5’-TTTGATGTCACGCACGATTT-3’.

Immunoblot analysis

Cells were lysed using cold RIPA buffer (50mM Tris-HCl, 150mM NaCl, 1% NP-40, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, and 0.1% SDS) supplemented with Protease and Phosphatase inhibitor cocktail (ThermoFisher, Waltham, MA). Cell lysates were incubated on ice for 30 min followed by centrifugation at 13,000 RPM for 15 min. The clarified supernatants containing soluble proteins were saved and used in subsequent immunoblot. Proteins were electrophoresed in 8% or 10% SDS-PAGE gel and transferred to nitrocellulose membrane (Bio-Rad Laboratories). Protein level was detected by Western blot as previously described (Zhang et al., 2010). The following primary antibodies were used: mouse anti-GRP78 antibody (1:5000; 610979; BD Biosciences); rabbit anti-ATF4 (CREB-2) (1:500; sc-200; Santa Cruz Biotechnology); mouse anti-β-actin (1:5000; A5316; Millipore-Sigma); rabbit anti-phospho Akt (Ser473) (1:1000; 4060; Cell Signaling); rabbit anti-Akt (1:1000, 9272, Cell Signaling); rabbit anti-phospho p70 S6 Kinase (1:1000, 9234, Cell Signaling). The following secondary antibodies were used: HRP-conjugated goat anti-mouse (1:2000; sc-2005), goat anti-rabbit (1:2000, sc-2004), mouse IgG kappa binding protein (1:2000; sc-516102), mouse anti-rabbit (1:2000, sc-2357) from Santa Cruz Biotechnology. Protein bands were visualized by ChemiDoc XRS+ imager (Bio-Rad Laboratories) and quantified by Image Lab Software Version 4.0.1 build 6 (Bio-Rad Laboratories).

Statistical Analysis

All pair wise comparisons were made using the two-tailed Student’s t test in Microsoft Excel.

Results

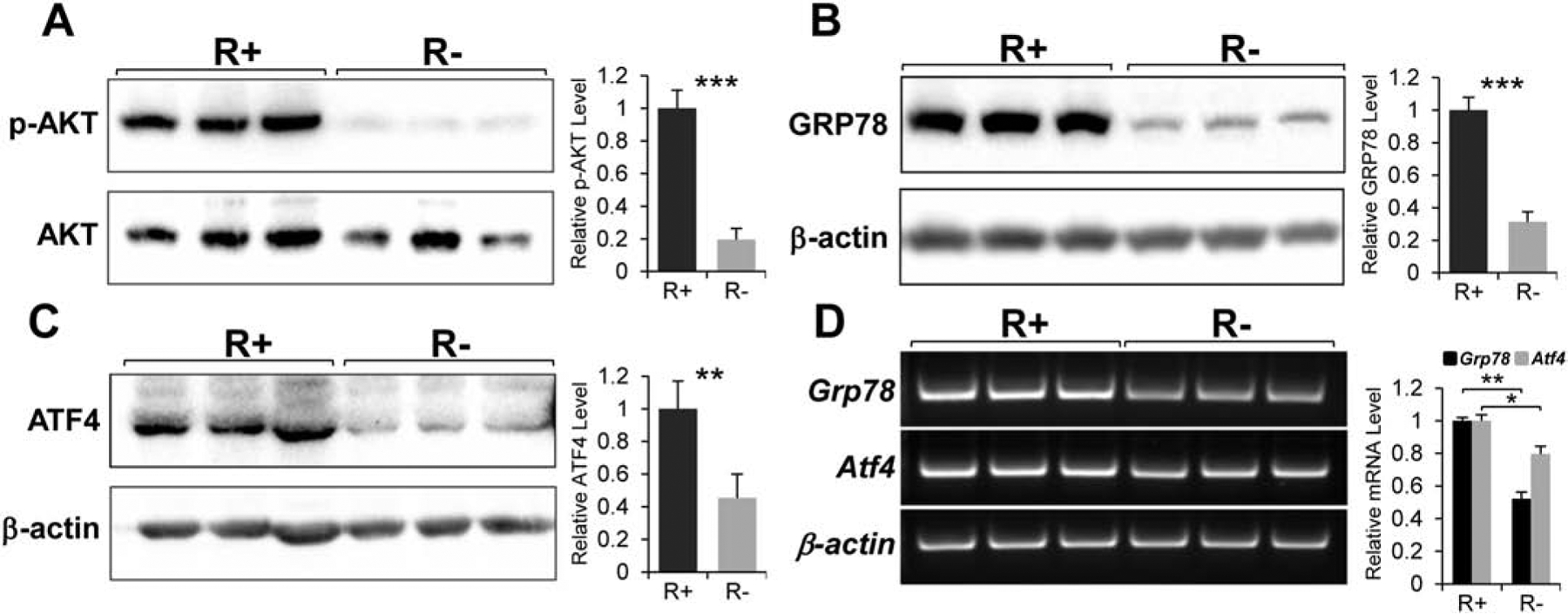

Levels of AKT activation, GRP78 and ATF4 are dependent on the integrity of the IGF-1 Receptor.

Based on the discovery that GRP78 is a downstream target of the IGF-1R signaling, we utilized a pair of mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) as model systems to investigate the detailed mechanism through which IGF-1R regulates GPR78 expression. R+ and R− are MEFs with IGF-1R overexpression or knock-out respectively. The cells were cultured under normal non-stressed culture condition (4.5g/L glucose, 10%FBS). In agreement with AKT activation as a major downstream effect of IGF-1 signaling (Chitnis et al., 2008), R+ cells expressed robust level of activated AKT (as measured by phosphorylation at Serine 473) whereas R− cell exhibited markedly reduced pAKT level compared to R+ cells (Fig. 1A). Corresponding with the pAKT level, R+ cells have significantly higher levels of GRP78 protein and mRNA compared to R− cells (Fig. 1B & D). Interestingly, we discovered that there was also a significant reduction in protein level and a modest reduction in mRNA level of the transcription factor ATF4 in R− cells compared to R+ cells (Fig. 1C & D). Since ATF4 is a transcription factor which can bind to and activate the Grp78 promoter, this raises the possibility that stimulation of GRP78 expression by IGF-1R signaling can be mediated through ATF4.

Fig. 1.

Effect of IGF-1R knock-out on the AKT activation and expression of GRP78 and ATF4. A. Total lysates from mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) with the IGF-1R over-expression (R+) or knock-out (R−) were subjected to immunoblot analysis to detect levels of the phosphorylated form of AKT (p-AKT; at serine473) and total AKT. B. Immunoblot analysis for the protein level of GRP78 with β-actin serving as loading control. C. Immunoblot analysis for ATF4 with β-actin serving as loading control. D. Expression levels of Grp78 and Atf4 mRNA analyzed by Reverse Transcription-PCR with β-actin mRNA serving as loading control (n=3). *P≤0.05, **P≤0.01, ***P≤0.001.

IGF-1 Receptor signaling regulates ATF4 and GRP78 expression via the PI3K/ATK/mTOR signal transduction pathway.

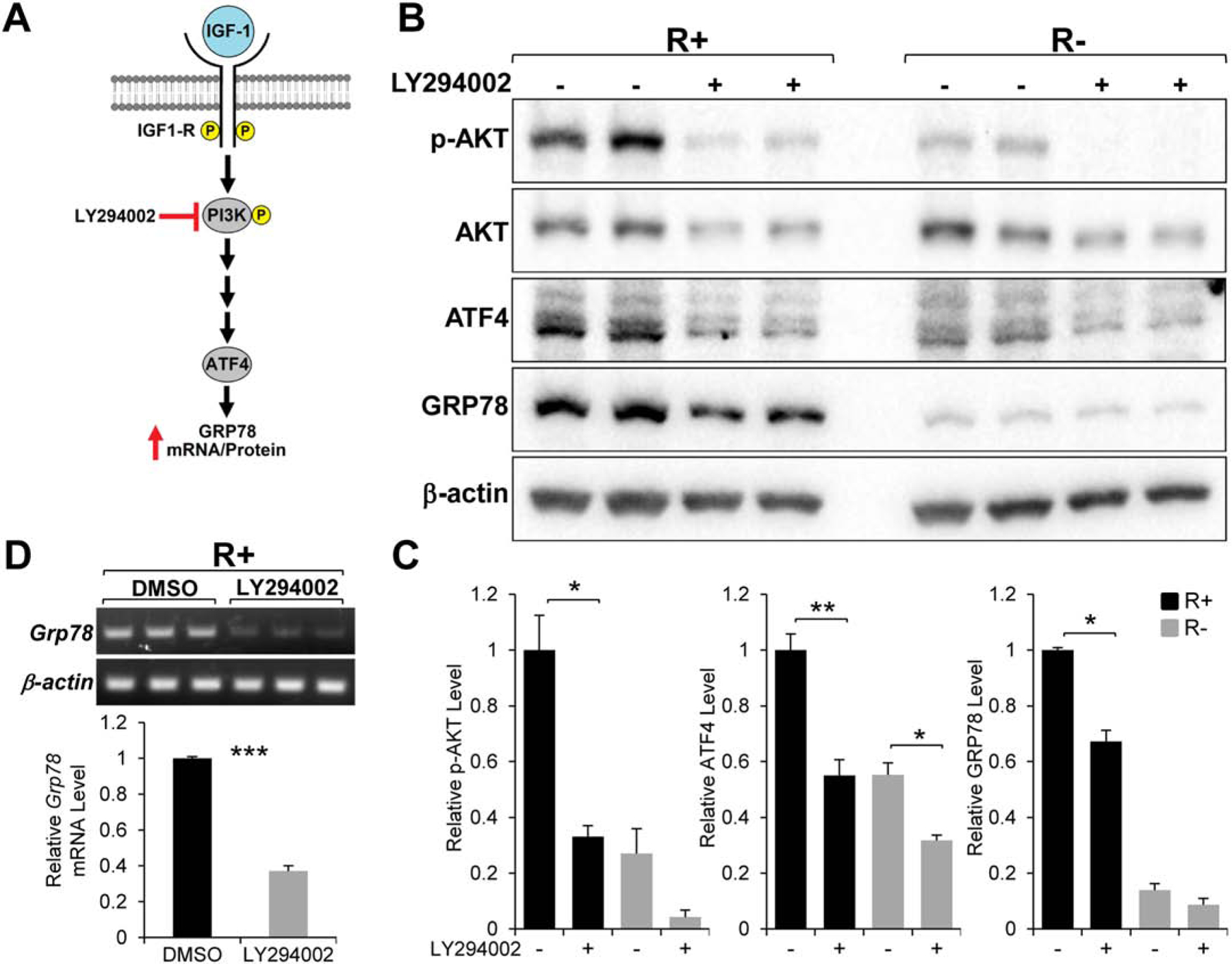

The canonical IGF-1 signaling pathway goes through both the PI3K/AKT/mTOR axis and the MAPK/ERK cascade (Cohen, 2006; Hakuno & Takahashi, 2018). As our previous study showed that the MAPK/ERK branch is unlikely to be involved in IGF-1R stimulation of GRP78 expression (Pfaffenbach et al., 2012), our current study focuses on dissecting the PI3K branch. Through the use of specific small molecule inhibitors, we seek to identify components of the PI3K signaling cascade that impact GRP78 expression mediated by IGF-1R.

Treatment of R+ and R− cells with LY294002, a specific inhibitor of PI3K (Fig. 2A) for 24 hours resulted in a dramatic decrease in the level of phosphorylated AKT (at Serine 473) in both cell lines (Fig. 2B & C). This is consistent with AKT being a major downstream target of PI3K (Cohen, 2006; Hakuno & Takahashi, 2018). Importantly, there was substantial reduction in both ATF4 and GRP78 protein levels in the cells treated with the drug (Fig. 2B & C). In addition, we observed a significant decrease in Grp78 mRNA in R+ cells treated with LY294002 (Fig. 2D). Taken together, these results suggest that PI3K plays an important role in the IGF-1R stimulation of GRP78 at the transcriptional level and this effect may be mediated through ATF4.

Fig. 2.

Effect of the PI3K inhibitor LY294002 on GRP78 and ATF4 expression. A. Proposed role of PI3K in IGF-1 stimulation of GRP78 expression. B. Immunoblot analysis of the level of phosphorylated AKT (p-AKT), total AKT, GRP78, and ATF4 with β-actin serving as loading control in R+ and R− cells which are either non-treated or treated with LY294002 for 24 hr. C. Quantitation of the relative level of the proteins showed in panel B (n=2). D. Grp78 mRNA expression in R+ cells treated with LY294002 for 24hr analyzed by RT-PCR with β-actin mRNA serving as loading control (n=3). *P≤0.05, **P≤0.01, ***P≤0.001.

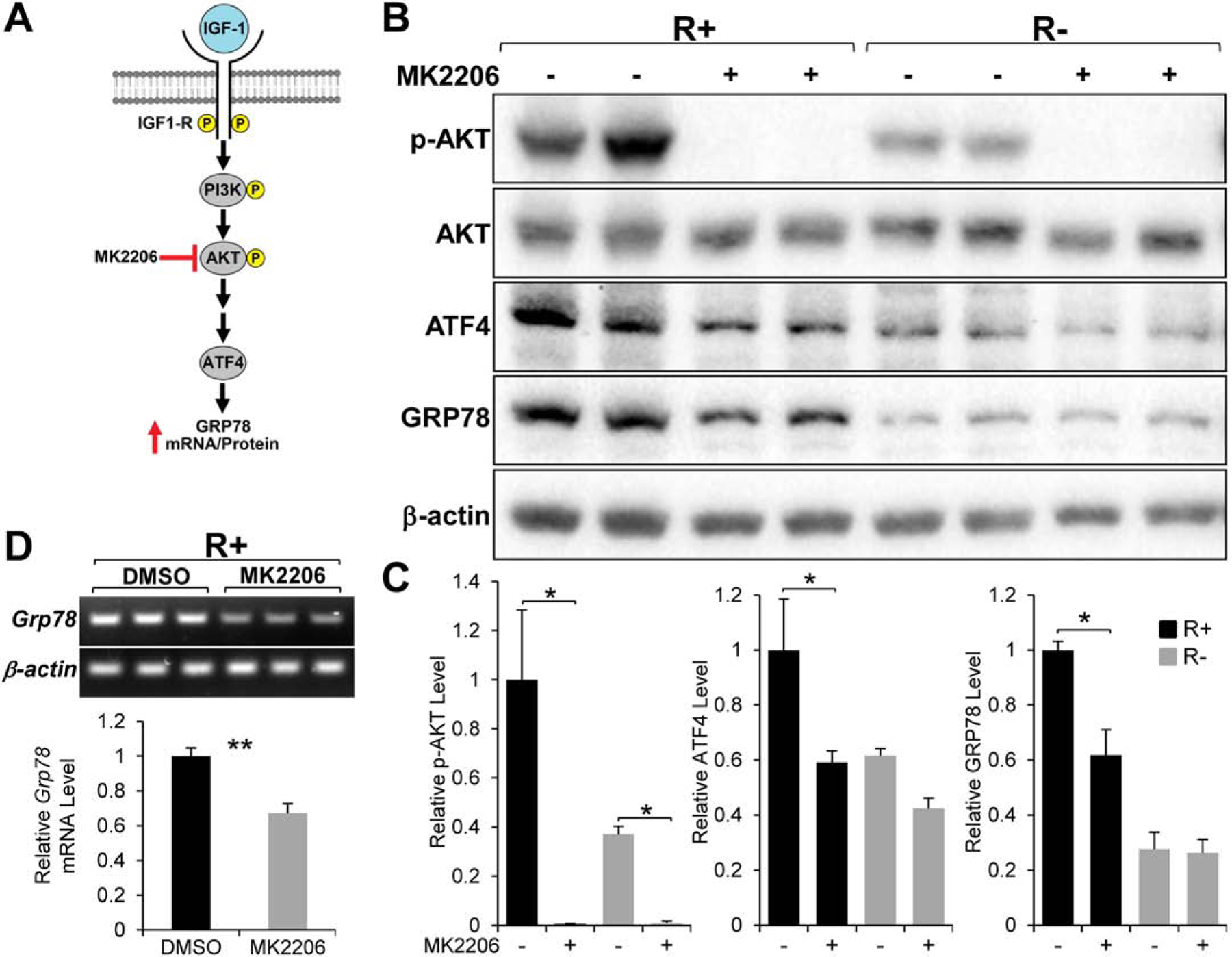

Next, we utilized MK2206 a specific AKT inhibitor to block its activity and determine the effect on GRP78 and ATF4 expression (Fig. 3A). As expected, AKT phosphorylation (at Serine 473) was completely inhibited in both R+ and R− cells treated with the drug for 24 hours demonstrating the potency of the compound. The reduction in AKT activation associated with significant decrease in GRP78 and ATF4 protein levels (Fig. 3B & C) as well as Grp78 mRNA level (Fig. 3D) in R+ cells similar to LY294002 treatment. These results imply that PI3K/AKT activity is required for IGF-1R-mediated stimulation of GRP78 expression with a possible involvement of ATF4.

Fig. 3.

Effect of the AKT inhibitor MK2206 on GRP78 and ATF4 expression. A. Proposed role of AKT in IGF-1 stimulation of GRP78 expression. B. Immunoblot analysis of the level of phosphorylated AKT (p-AKT), total AKT, GRP78, and ATF4 with β-actin serving as loading control in R+ and R− cells treated with MK2206 for 24 hr. C. Quantitation of the protein levels showed in panel B (n=2). D. Grp78 mRNA expression in R+ cells treated with MK2206 for 24hr analyzed by RT-PCR with β-actin mRNA serving as loading control (n=3). *P≤0.05, **P≤0.01.

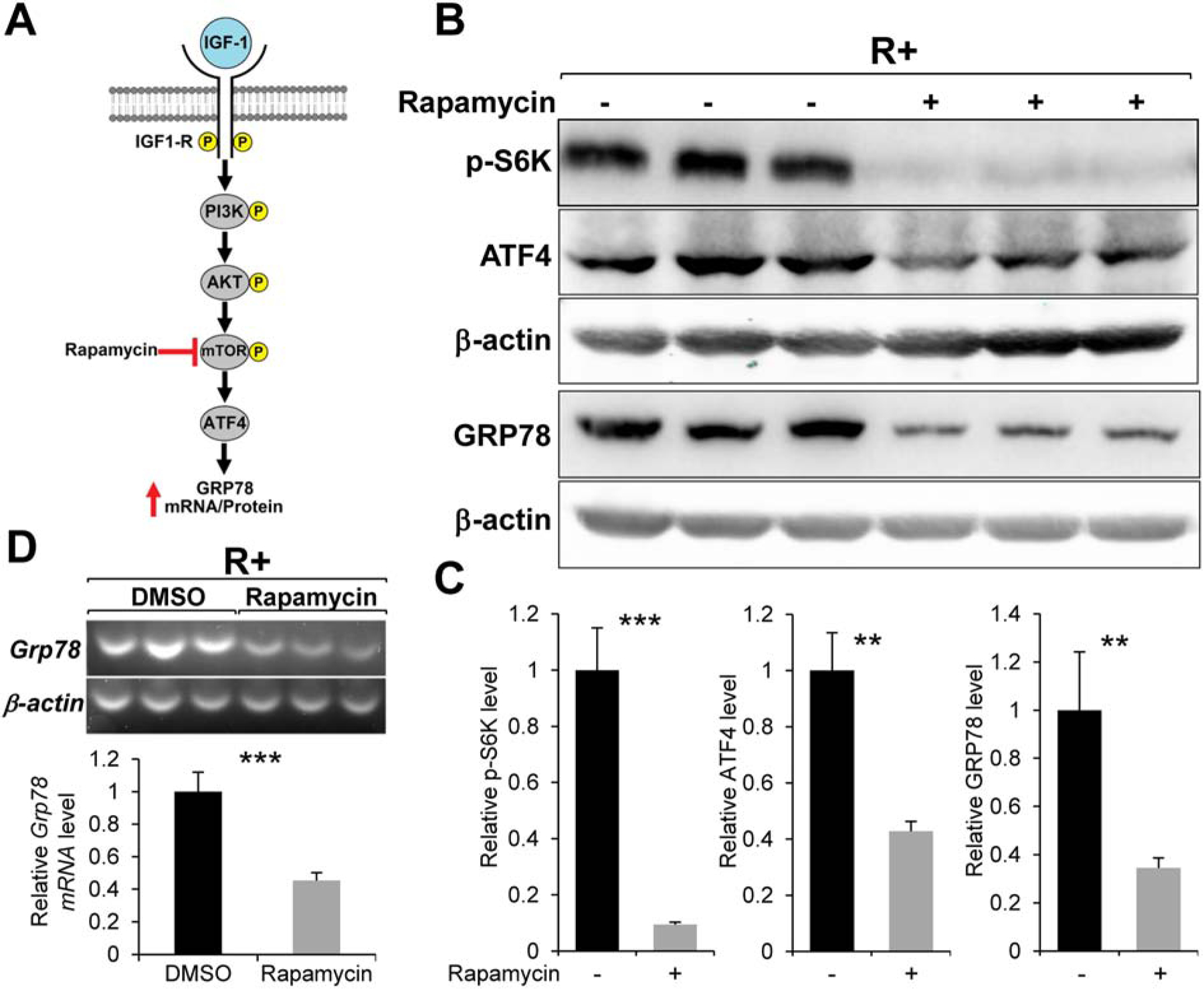

A well-known downstream target of AKT is mTOR (Saxton & Sabatini, 2017). Importantly, several recent studies showed that mTOR can directly enhance ATF4 translation (Ben-Sahra et al., 2016; Park et al., 2017; Selvarajah et al., 2019). Thus, we tested the effect of Rapamycin, a specific inhibitor of mTOR, on IGF-1R stimulation of GRP78 expression (Fig. 4A). Rapamycin treatment in R+ cells led to a dramatic reduction the phosphorylation level of p70 S6 Kinase (at threonine 389), which is a well-established downstream target of mTOR (Saxton & Sabatini, 2017), demonstrating the potency of the compound (Fig. 4B & C). Similar to LY294002 and MK2206, R+ cells treated with Rapamycin showed a significant reduction in both GRP78 and ATF4 protein levels (Fig. 4B & C) as well as Grp78 mRNA level (Fig. 4D). Collectively, these small molecule inhibitor experiments demonstrated that the PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling axis is critical for GRP78 expression in IGF-1R overexpressing cells and this effect is likely at the transcriptional level mediated by ATF4.

Fig. 4.

Effect of the mTOR inhibitor Rapamycin on GRP78 and ATF4 expression. A. Proposed role of mTOR in IGF-1 stimulation of GRP78 expression. B. Immunoblot analysis of the level of phosphorylated p70 S6 kinase (p-S6K), GRP78 and ATF4 with β-actin serving as loading control in R+ cells treated with Rapamycin for 24hr. C. Quantitation of the protein levels showed in panel B (n=3). D. Grp78 mRNA expression in R+ cells treated with Rapamycin for 24hr analyzed by RT-PCR with β-actin mRNA serving as loading control (n=3). **P≤0.01, ***P≤0.001.

GRP78 expression in cells overexpressing IGF-1 receptor requires ATF4.

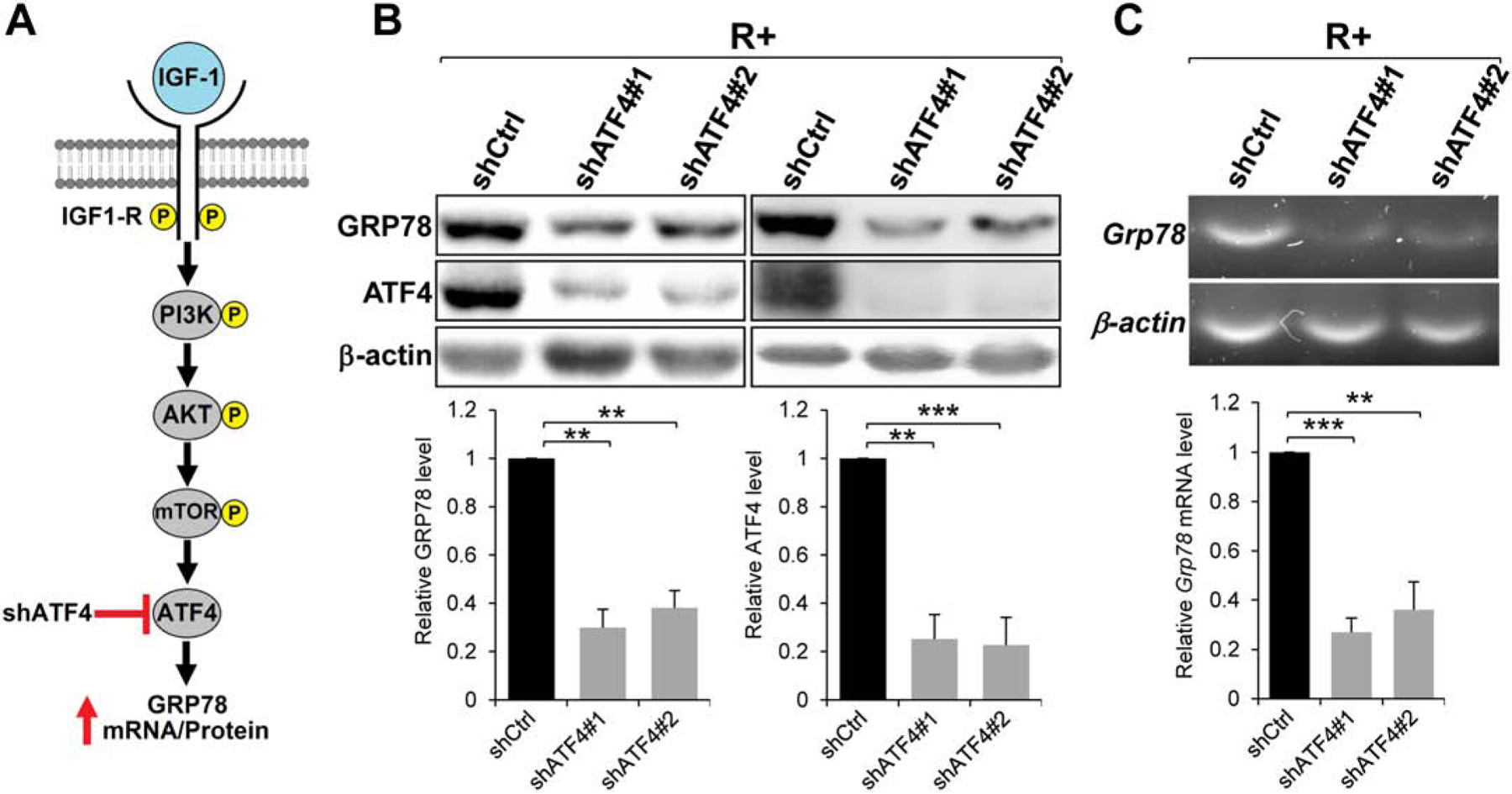

To test directly the requirement of ATF4 on GRP78 expression in R+ cells, we employed RNA interference to knock-down ATF4 in such cells via lentiviral transduction of two distinct shRNA constructs targeting ATF4 mRNA (Fig. 5A). After puromycin selection, we obtained two stable R+ cell lines expressing two different shATF4s. These R+ cell lines exhibited up to 75% knock-down efficiency for ATF4 compared to R+ cell line stably expressing control shRNA (Fig. 5B). Importantly, knock-down of ATF4 in these cell lines resulted in an approximately 70% reduction in both GPR78 protein (Fig. 5B) and mRNA levels (Fig. 5C). These data indicate the requirement of ATF4 in GRP78 expression in MEFs overexpressing the IGF-1R.

Fig. 5.

Effect of ATF4 knock-down by shRNA on GRP78 expression. A. Proposed role of ATF4 in IGF-1 stimulation of GRP78 expression. B. Immunoblot analysis of GRP78 and ATF4 protein levels in R+ cells expressing two independent shRNAs (#1 and #2) targeting ATF4 with β-actin serving as loading control (n=3). C. RT-PCR analysis of Grp78 mRNA expression in R+ cells transduced by Lentivirus expressing shRNAs targeting ATF4 as in panel B with β-actin mRNA serving as loading control (n=2). **P≤0.01, ***P≤0.001.

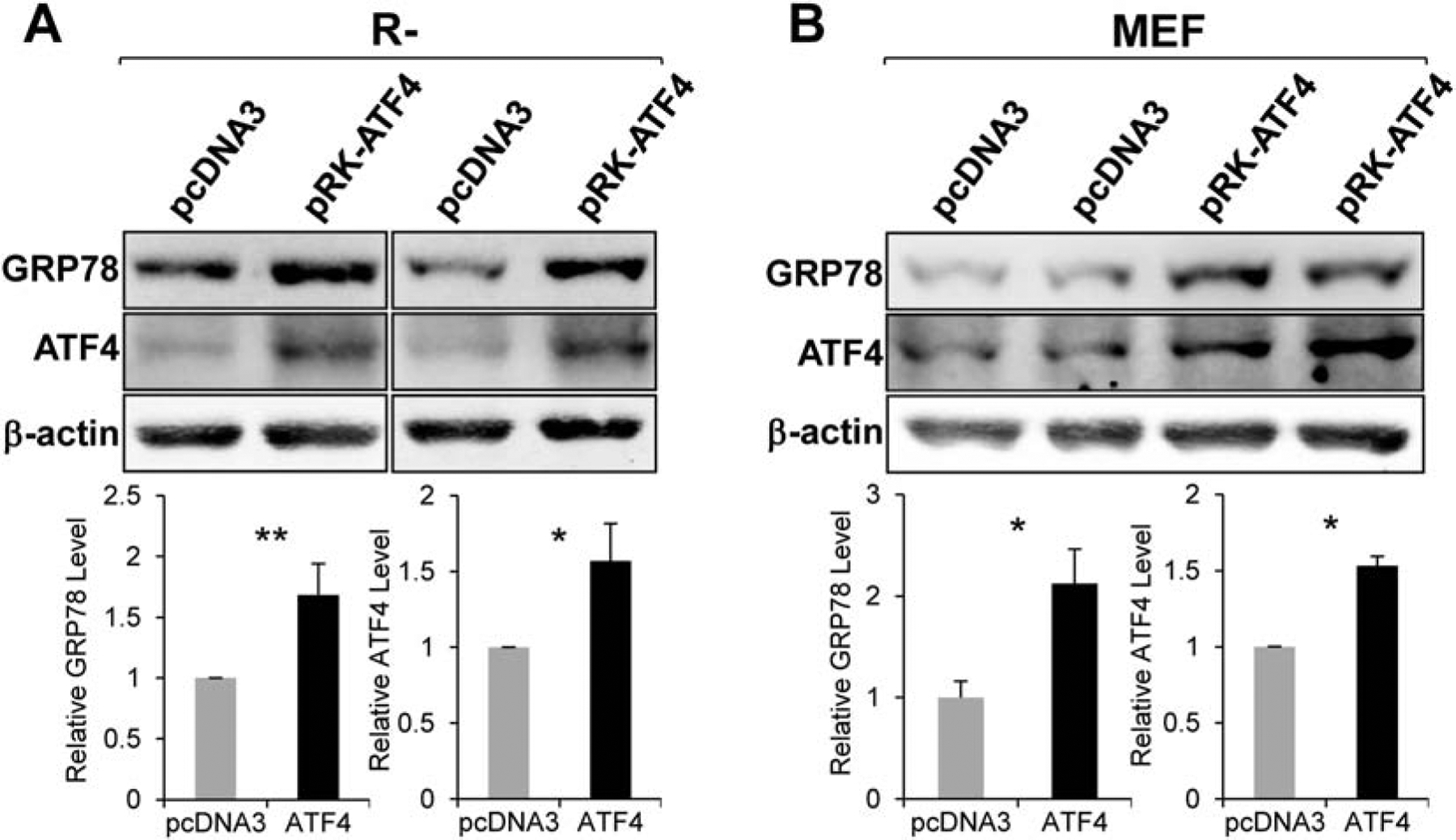

To further determine whether ectopic expression of ATF4 can rescue GRP78 expression in R− cells, we overexpressed ATF4 in R− cells and observed a 1.7-fold increase in GRP78 protein level compared to vector control (Fig. 6A). Similarly, enforced expression of ATF4 in wild type MEFs led to a 2.1-fold increase in GRP78 protein level (Fig. 6B). Collectively, these results establish that the transcription factor ATF4 is sufficient for elevating GRP78 expression in cells devoid of IGF-1R and in wild type MEFs.

Fig. 6.

Effect of ATF4 overepxression on GRP78 protein level. Immunoblot analyses of GRP78 and ATF4 protein levels in R− cells (n=3) (Panel A) or MEFs (n=2) (Panel B) transfected with empty vector pcDNA3 or vector expressing ATF4 (pRK-ATF4) with β-actin serving as loading control. *P≤0.05, **P≤0.01.

AKT activation and increase in ATF4 precede GRP78 elevation in mouse embryonic fibroblasts following growth factor stimulation.

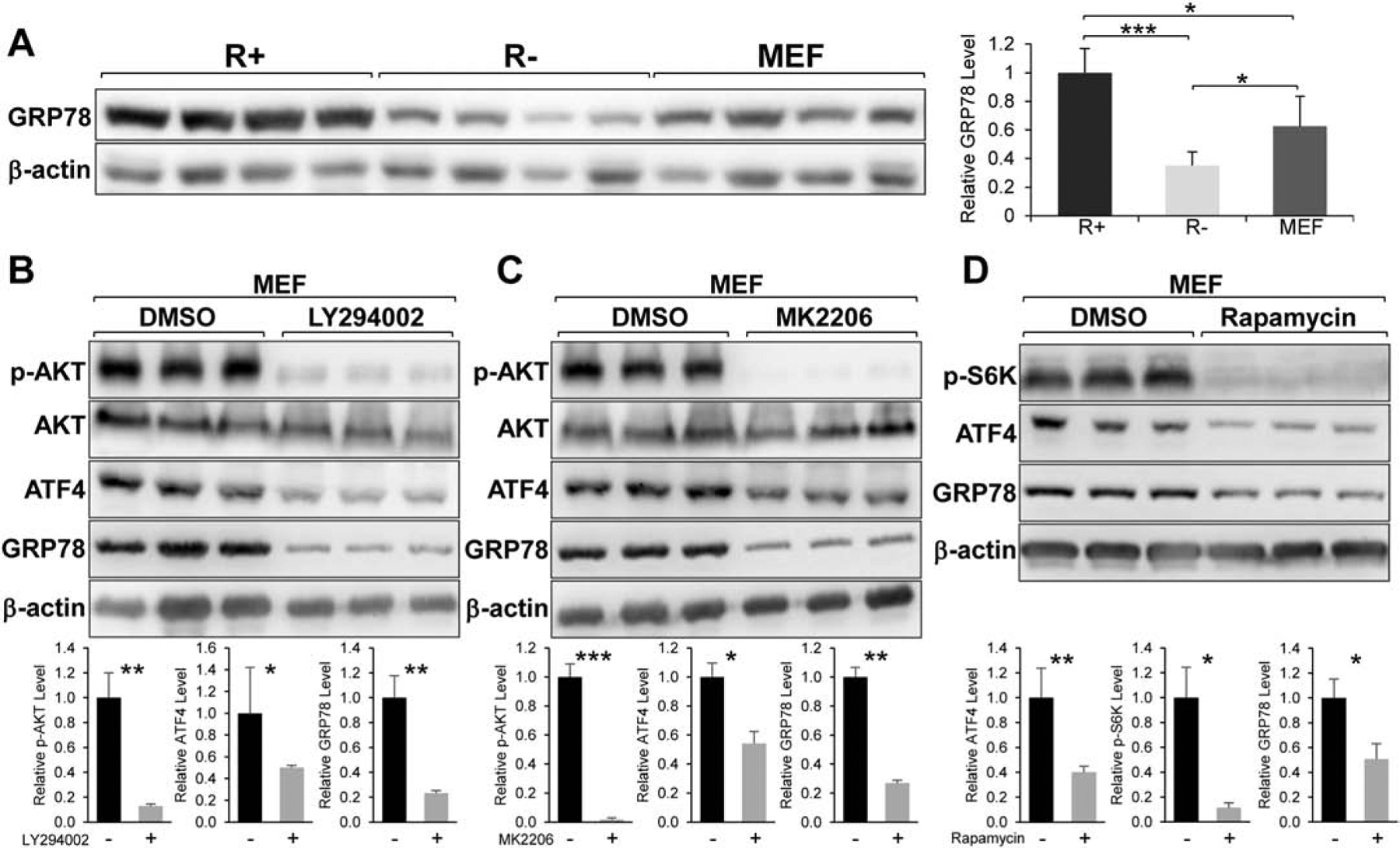

While R+ and R− cells with IGF-1R overexpression or knock-out respectively are useful as model systems for studying the effect of IGF-1 signaling, we next investigated whether growth factor signaling in a more natural setting such as IGF-1 or serum stimulation of wild type MEFs may also associate with increase in AKT activation and ATF4 induction. Interestingly, the GRP78 expression level in wild type MEFs is intermediate between R+ and R− cells (Fig. 7A). This supports the notion that MEFs cultured under normal conditions with endogenous level of IGF-1R express moderate level of GRP78, which is decreased upon IGF-1R depletion and increased upon IGF-1R over-expression. To confirm the observations in R+ and R− cells, we treated MEFs with LY294002, MK2206, and Rapamycin for 24 hours and analyzed the expression level of GRP78 and ATF4 by Western blot. Similar to R+ cells, MEFs treated with LY294002 and MK2206 showed a dramatic reduction in phosphorylated AKT and a significant decrease in ATF4 and GRP78 protein levels (Fig. 7B & C). Likewise, MEFs treated with Rapamycin exhibited markedly diminished level of phosphorylated p78 S6 kinase and substantial reduction in ATF4 and GRP78 protein levels (Fig. 7D). These data demonstrated that the PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling pathway is important for ATF4 and GRP78 expression in wild type MEFs similar to R+ cells.

Fig. 7.

Effects of small molecule inhibitors of PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling in MEFs. A. Relative expression level of GRP78 protein in R+, R−, and MEFs with β-actin serving as loading control (n=4). B & C. Immunoblot analysis of the levels of phosphorylated AKT (p-AKT), total AKT, GRP78 and ATF4 with β-actin serving as loading control in MEFs treated with LY294002 or MK2206 for 24 hr (n=3). D. Immunoblot analysis of the levels of phosphorylated p70 S6 kinase (p-S6K), GRP78, and ATF4 with β-actin serving as loading control in MEFs treated with Rapamycin for 24 hr (n=3). *P≤0.05, **P≤0.01, ***P≤0.001.

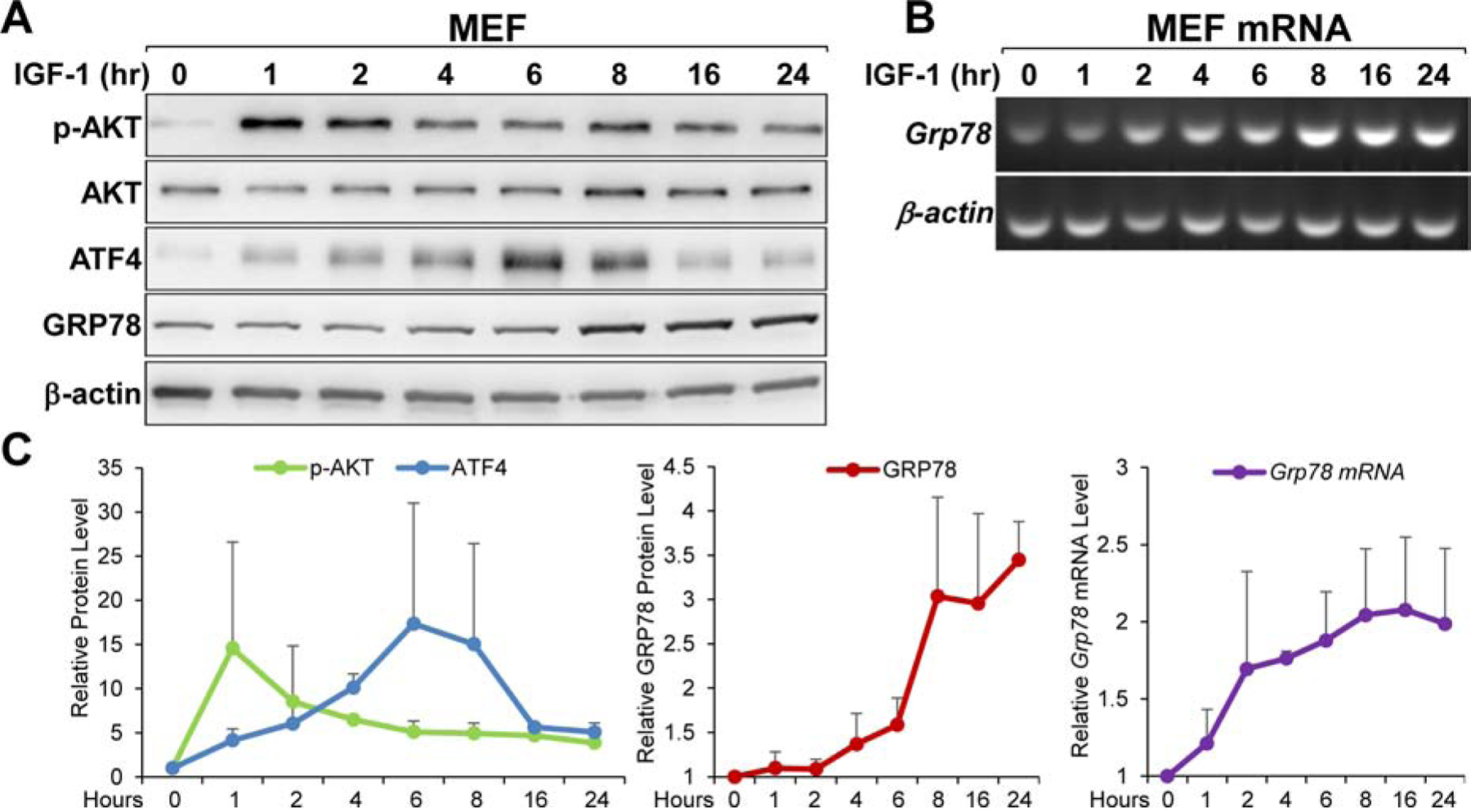

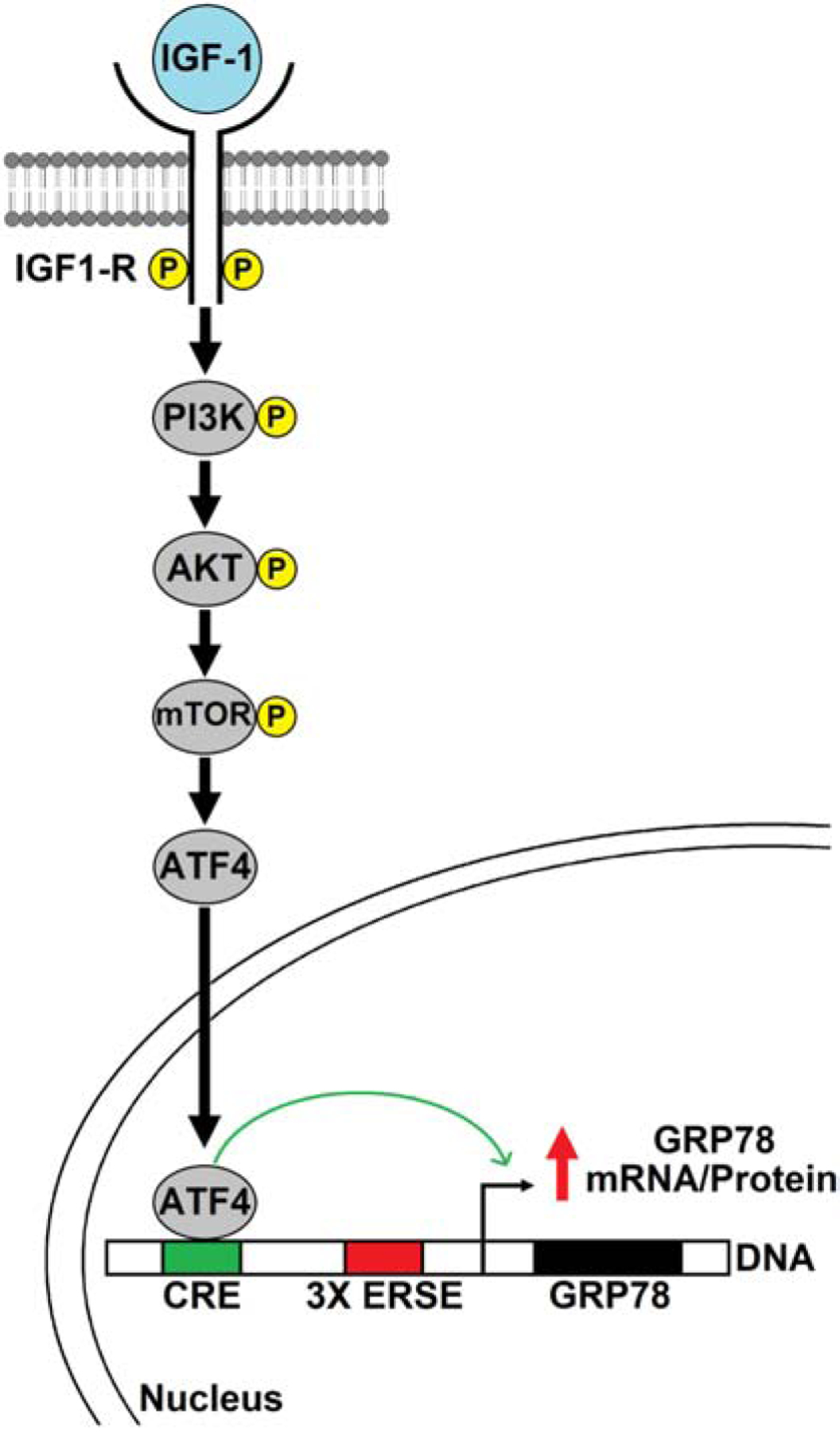

To analyze the kinetics of induction upon IGF-1 or serum stimulation, MEFs were cultured in serum-free media for 48 hours and then stimulated with media containing IGF-1 (100ng/ml) or 10% fetal bovine serum for a 24-hour time course. As expected, AKT phosphorylation was strongly induced by IGF-1 addition, peaking at the 1-hour time point and gradually subsided afterward (Fig. 8A & C). Importantly, we observed a strong, early, and sustained induction of ATF4 protein upon serum stimulation starting at the 1-hour time point and lasting through the 8-hour time point. This early increase in ATF4 occurred concurrently with an increase in Grp78 mRNA (Fig. 8B & C), which preceded the increase in GRP78 protein level (Fig. 8A & C). Similar results were observed with serum stimulation (Fig. S1). These data are consistent with a sequence of events starting from AKT activation at the earlier time points leading to concomitant accumulation of ATF4. As a transcription factor, ATF4 activates Grp78 promoter resulting in an increase in its mRNA, preceding increase in GRP78 protein levels due to the delayed nature of protein synthesis. As summarized in Fig. 9, this current study delineated the PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling cascade involved in the IGF-1R mediated stimulation of GRP78 expression and identified ATF4 as the key transcription factor for this effect.

Fig. 8.

Kinetics of GRP78 and ATF4 induction in MEFs following IGF-1 stimulation. A. MEFs were cultured in serum-free medium for 48 hours, and then stimulated with IGF-1 (100ng/ml) for the indicated time. Cell lysates were analyzed by immunoblot for AKT activation (p-AKT), AKT, GRP78 and ATF4 levels with β-actin serving as loading control. B. Same as in panel A but Grp78 mRNA was analyzed by RT-PCR with β-actin mRNA serving as loading control. C. Quantitation of the induction profile for the indicated proteins and mRNA shown in panel A and B (n=2).

Fig. 9.

Proposed model of IGF-1R mediated stimulation of GRP78 via the transcription factor ATF4. Upon ligand stimulation, the IGF-1R activates the PI3K-AKT-mTOR pathway resulting in increased expression of the transcription factor ATF4 which binds to the cAMP Response Element (CRE) in the promoter region of Grp78 gene and upregulates its transcription, leading to increase in GRP78 protein expression.

Discussion

IGF-1R, as a major regulator of cellular proliferation, survival, metabolism and differentiation, controls a plethora of cellular activities through its two major signaling cascades: the MAPK/ERK and the PI3K/AKT pathways (Cohen, 2006; Hakuno & Takahashi, 2018). As such, it is important to understand the precise molecular mechanisms through which IGF-1R exerts its effects on the cells. GRP78 is an essential ER chaperone responsible for folding and processing of membrane bound and secretory proteins as well as serving as the master regulator of the UPR (Lee, 2014; B. Luo & Lee, 2013; Ni & Lee, 2007). In this role, GRP78 can affect many critical cellular processes and plays a vital part in cell survival under different forms of stress (Lee, 2014; B. Luo & Lee, 2013). Additionally, GRP78 can be translocated to other cellular compartments where it assumes multiple new functions beyond the ER (Ni et al., 2011; Tsai et al., 2018; Tseng et al., 2019; Zhang et al., 2010). Thus, our discovery that GRP78 is a downstream target of IGF-1R provides a new angle on how the pro-survival and pro-growth effects of IGF-1 signaling are executed at the molecular level (Pfaffenbach et al., 2012). However, the determining factors of the signaling cascade mediating the IGF-1R effect are still unknown. Interestingly, a previous study has reported that IGF-1 can augment GRP78 expression during ER stress and protect cells from ER stress-induced apoptosis although the mechanism for this effect was not determined (Novosyadlyy et al., 2008). Another study showed that inhibition of AKT mitigates GRP78 expression in endometrial cancer (Gray et al., 2013). In this present study, we identify ATF4 as the critical transcription factor linking IGF-1R signaling to stimulation of GRP78 expression.

Here we demonstrated that suppression of the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway via small molecule inhibitors resulted in concurrent decrease in both GRP78 and ATF4 protein levels in the R+ cells suggesting a possible link between the two. Direct knock-down of ATF4 via shRNA in the R+ cells led to a decrease in both GRP78 protein and mRNA levels. Conversely, overexpression of ATF4 in R− and MEFs increased GRP78 protein level. As a transcription factor, ATF4 effect on GRP78 expression is likely at the transcriptional level. We have previously reported that the Grp78 promoter contains a CRE site upstream of the ER stress-response element (ERSE) and that ATF4 is capable of binding to this CRE sequence and activates GRP78 transcription (Alexandra et al., 1991; S. Luo et al., 2003). This is consistent with our observation here that ATF4 knock-down decreased Grp78 mRNA level in the R+ cells. As bZIP transcription factors, ATF/CREB family members are known to form homodimers or heterodimers with other bZIP transcription factors such as c-fos or c-jun to regulate transcription (Ameri & Harris, 2008). Therefore, it remains to be determined whether ATF4 acts alone or in concert with other bZIP proteins to regulate GRP78 expression upon activation of IGF-1R. Taken together, our findings suggest that IGF-1R signaling stimulation of GRP78 expression is mediated by ATF4 at the promoter level to enhance transcription.

The PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway is a well-established downstream effector of IGF-1R (Cohen, 2006; Hakuno & Takahashi, 2018) while ATF4 is a master transcription factor for the integrated stress response (Pakos-Zebrucka et al., 2016). This raises the important question on how mTOR, as the distal kinase in the pathway, affects ATF4 level in R+ and R− cells grown under normal culture conditions. ATF4 expression is traditionally regulated at the translational level during stress response via the phosphorylation of the translation initiation factor eIF2α by four kinases: PERK, PKR, GCN2, and HRI (Pakos- Zebrucka et al., 2016; Wek, 2018). Phosphorylation of eIF2α leads to attenuation of global translation but paradoxically enhances the translation of select mRNA transcripts including ATF4 that help with the stress response (Pakos-Zebrucka et al., 2016; Wek, 2018). However, several recent studies have revealed that mTOR can directly enhance ATF4 translation and bypass eIF2α phosphorylation by employing the 4E-binding protein family of translation repressors as well as stabilization of Atf4 mRNA (Ben-Sahra et al., 2016; Park et al., 2017; Selvarajah et al., 2019). This lends support to our current finding here that mTOR can affect ATF4 level independent of ER stress signaling in the R+ cells under normal culture condition.

As R+ and R− cells are genetically modified cells with IGF-1R overexpression or knock-down respectively, they might introduce un-intended artifacts in their responses to IGF-1. To circumvent this potential issue, we utilized normal MEFs with endogenous expression level of IGF-1R to probe the response to growth factor stimulation. IGF-1 or serum stimulation of these cells after prolonged growth factor starvation showed a robust and early increase in phosphorylation of AKT and ATF4 protein as well as Grp78 mRNA followed by increase in GRP78 protein. These observations support our proposed model (Fig. 9) which suggests a cascade whereby IGF-1R stimulation activates PI3K/AKT/mTOR activity leading to ATF4 induction, Grp78 transcriptional activation and protein elevation. It is important to note that fetal bovine serum contains not only IGF-1 but also a plethora of other growth factors such as EGF and FGF. While insulin, a factor highly similar to IGF-1, is reported to induce GRP78 expression during ER stress via augmentation of ATF4 in human neuroblastoma cells (Inageda, 2010), another study showed that VEGF can induce GRP78 expression in the human endothelial cell line HUVEC during angiogenesis (Zou et al., 2019). Thus, further investigation is warranted to determine the effect of various growth factors the on the expression of GRP78 and whether ATF4 is a unifying factor. These findings could have important implications on how GRP78 is regulated by growth factors to promote growth in health and disease.

Supplementary Material

Fig. S1. Kinetics of GRP78 and ATF4 induction in MEFs following serum stimulation. A. MEFs were cultured in serum-free medium for 48 hours, and then stimulated with serum for the indicated time. Cell lysates were analyzed by immunoblot for AKT activation (p-AKT), AKT, GRP78 and ATF4 levels with β-actin serving as loading control. B. Same as in panel A but Grp78 mRNA was analyzed by RT-PCR with β-actin mRNA serving as loading control. C. Quantitation of the induction profile for the indicated proteins and mRNA shown in panel A and B.

Acknowledgements

We thank Drs. S. Korsmeyer, R. Baserga and Y Ye for the gift of cell lines and reagents. This work was supported in part by National Institutes of Health grant CA027607 to A.S.L.

Funding Information

National Institutes of Health Grant/Award Number: CA027607

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of Interests

The authors declare that there are no conflict of interests.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

- Alexandra S, Nakaki T, Vanhamme L, & Lee AS (1991). A binding site for the cyclic adenosine 3′,5′-Monophosphate-Response element-Binding protein as a regulatory element in the grp78 promoter. Molecular Endocrinology. 10.1210/mend-5-12-1862 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ameri K, & Harris AL (2008). Activating transcription factor 4. In International Journal of Biochemistry and Cell Biology. 10.1016/j.biocel.2007.01.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Sahra I, Hoxhaj G, Ricoult SJHH, Asara JM, & Manning BD (2016). mTORC1 induces purine synthesis through control of the mitochondrial tetrahydrofolate cycle. Science. 10.1126/science.aad0489 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Booth L, Roberts JL, Cash DR, Tavallai S, Jean S, Fidanza A, Cruz-Luna T, Siembiba P, Cycon KA, Cornelissen CN, Dent P (2015). GRP78/BiP/HSPA5/DNA K is a universal therapeutic target for human disease. Journal of Cellular Physiology. 10.1002/jcp.24919 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casas C (2017). GRP78 at the centre of the stage in cancer and neuroprotection. In Frontiers in Neuroscience. 10.3389/fnins.2017.00177 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chitnis MM, Yuen JSPP, Protheroe AS, Pollak M, & Macaulay VM (2008). The type 1 insulin-like growth factor receptor pathway. In Clinical Cancer Research. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-4879 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen P (2006). Overview of the IGF-I system. In Hormone Research. 10.1159/000090640 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook KL, & Clarke R (2015). Role of GRP78 in promoting therapeutic-resistant breast cancer. In Future Medicinal Chemistry. 10.4155/fmc.15.80 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diehl JA, Fuchs SY, & Koumenis C (2011). The cell biology of the unfolded protein response. Gastroenterology. 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.05.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drakas R, Tu X, & Baserga R (2004). Control of cell size through phosphorylation of upstream binding factor 1 by nuclear phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 10.1073/pnas.0403328101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray MJ, Mhawech-Fauceglia P, Yoo E, Yang W, Wu E, Lee AS, & Lin YG (2013). AKT inhibition mitigates GRP78 (glucose-regulated protein) expression and contribution to chemoresistance in endometrial cancers. International Journal of Cancer. 10.1002/ijc.27994 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hai T, & Hartman MG (2001). The molecular biology and nomenclature of the activating transcription factor/cAMP responsive element binding family of transcription factors: Activating transcription factor proteins and homeostasis. In Gene. 10.1016/S0378-1119(01)00551-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hakuno F, & Takahashi S-I (2018). IGF1 receptor signaling pathways. Journal of Molecular Endocrinology. 10.1530/JME-17-0311 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inageda K (2010). Insulin modulates induction of glucose-regulated protein 78 during endoplasmic reticulum stress via augmentation of ATF4 expression in human neuroblastoma cells. FEBS Letters. 10.1016/j.febslet.2010.07.040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lebeaupin C, Yong J, & Kaufman RJ (2020). The Impact of the ER Unfolded Protein Response on Cancer Initiation and Progression: Therapeutic Implications. Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology. 10.1007/978-3-030-40204-4_8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee AS (2014). Glucose-regulated proteins in cancer: Molecular mechanisms and therapeutic potential. In Nature Reviews Cancer. 10.1038/nrc3701 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo B, & Lee AS (2013). The critical roles of endoplasmic reticulum chaperones and unfolded protein response in tumorigenesis and anticancer therapies. In Oncogene. 10.1038/onc.2012.130 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo S, Baumeister P, Yang S, Abcouwer SF, & Lee AS (2003). Induction of Grp78/BiP by Translational Block. Journal of Biological Chemistry, 278(39), 37375–37385. 10.1074/jbc.M303619200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo S, Mao C, Lee B, & Lee AS (2006). GRP78/BiP Is Required for Cell Proliferation and Protecting the Inner Cell Mass from Apoptosis during Early Mouse Embryonic Development. Molecular and Cellular Biology. 10.1128/mcb.00779-06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ni M, & Lee AS (2007). ER chaperones in mammalian development and human diseases. In FEBS Letters. 10.1016/j.febslet.2007.04.045 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ni M, Zhang Y, & Lee AS (2011). Beyond the endoplasmic reticulum: Atypical GRP78 in cell viability, signalling and therapeutic targeting. In Biochemical Journal. 10.1042/BJ20101569 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novosyadlyy R, Kurshan N, Lann D, Vijayakumar A, Yakar S, & LeRoith D (2008). Insulin-like growth factor-I protects cells from ER stress-induced apoptosis via enhancement of the adaptive capacity of endoplasmic reticulum. Cell Death and Differentiation. 10.1038/cdd.2008.52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pakos-Zebrucka K, Koryga I, Mnich K, Ljujic M, Samali A, & Gorman AM (2016). The integrated stress response. EMBO Reports. 10.15252/embr.201642195 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park Y, Reyna-Neyra A, Philippe L, & Thoreen CC (2017). mTORC1 Balances Cellular Amino Acid Supply with Demand for Protein Synthesis through Post-transcriptional Control of ATF4. Cell Reports. 10.1016/j.celrep.2017.04.042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pathria G, Lee JS, Hasnis E, Tandoc K, Scott DA, Verma S, Feng Y, Larue L, Sahu AD, Topisirovic I, Ruppin E, & Ronai ZAZA (2019). Translational reprogramming marks adaptation to asparagine restriction in cancer. Nature Cell Biology. 10.1038/s41556-019-0415-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfaffenbach KT, Pong M, Morgan TE, Wang H, Ott K, Zhou B, Longo VD, & Lee AS (2012). GRP78/BiP is a novel downstream target of IGF-1 receptor mediated signaling. Journal of Cellular Physiology. 10.1002/jcp.24090 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roller C, & Maddalo D (2013). The molecular chaperone GRP78/BiP in the development of chemoresistance: Mechanism and possible treatment. In Frontiers in Pharmacology. 10.3389/fphar.2013.00010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saxton RA, & Sabatini DM (2017). mTOR Signaling in Growth, Metabolism, and Disease. In Cell. 10.1016/j.cell.2017.02.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sell C, Rubini M, Rubin R, Liu JP, Efstratiadis A, & Baserga R (1993). Simian virus 40 large tumor antigen is unable to transform mouse embryonic fibroblasts lacking type 1 insulin-like growth factor receptor. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 10.1073/pnas.90.23.11217 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selvarajah B, Azuelos I, Platé M, Guillotin D, Forty EJ, Contento G, Woodcock H. v., Redding M, Taylor A, Brunori G, Durrenberger PF, Ronzoni R, Blanchard AD, Mercer PF, Anastasiou D, & Chambers RC (2019). MTORC1 amplifies the ATF4-dependent de novo serine-glycine pathway to supply glycine during TGF-1-induced collagen biosynthesis. Science Signaling. 10.1126/scisignal.aav3048 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen J, Ha DP, Zhu G, Rangel DF, Kobielak A, Gill PS, Groshen S, Dubeau L, & Lee AS (2017). GRP78 haploinsufficiency suppresses acinar-to-ductal metaplasia, signaling, and mutant Kras-driven pancreatic tumorigenesis in mice. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 10.1073/pnas.1616060114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singleton DC, & Harris AL (2012). Targeting the ATF4 pathway in cancer therapy. In Expert Opinion on Therapeutic Targets. 10.1517/14728222.2012.728207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staschke KA, & Wek RC (2019). Adapting to cell stress from inside and out. In Nature Cell Biology. 10.1038/s41556-019-0354-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tameire F, Verginadis II, Leli NM, Polte C, Conn CS, Ojha R, Salas Salinas C, Chinga F, Monroy AM, Fu W, Wang P, Kossenkov A, Ye J, Amaravadi RK, Ignatova Z, Fuchs SY, Diehl JA, Ruggero D, & Koumenis C (2019). ATF4 couples MYC-dependent translational activity to bioenergetic demands during tumour progression. Nature Cell Biology. 10.1038/s41556-019-0347-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai YL, Ha DP, Zhao H, Carlos AJ, Wei S, Pun TK, Wu K, Zandi E, Kelly K, & Lee AS (2018). Endoplasmic reticulum stress activates SRC, relocating chaperones to the cell surface where GRP78/CD109 blocks TGF-β signaling. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 10.1073/pnas.1714866115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tseng CC, Stanciauskas R, Zhang P, Woo D, Wu K, Kelly K, Gill PS, Yu M, Pinaud F, & Lee AS (2019). GRP78 regulates CD44v membrane homeostasis and cell spreading in tamoxifen-resistant breast cancer. Life Science Alliance. 10.26508/lsa.201900377 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wek RC (2018). Role of eIF2α kinases in translational control and adaptation to cellular stress. Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Biology. 10.1101/cshperspect.a032870 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye R, Jung DY, Jun JY, Li J, Luo S, Ko HJ, Kim JK, & Lee AS (2010). Grp78 heterozygosity promotes adaptive unfolded protein response and attenuates diet-induced obesity and insulin resistance. Diabetes. 10.2337/db09-0755 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Liu R, Ni M, Gill P, & Lee AS (2010). Cell surface relocalization of the endoplasmic reticulum chaperone and unfolded protein response regulator GRP78/BiP. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 10.1074/jbc.M109.087445 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu G, & Lee AS (2015). Role of the unfolded protein response, GRP78 and GRP94 in organ homeostasis. Journal of Cellular Physiology. 10.1002/jcp.24923 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zou J, Fei Q, Xiao H, Wang H, Liu K, Liu M, Zhang H, Xiao X, Wang K, & Wang N (2019). VEGF-A promotes angiogenesis after acute myocardial infarction through increasing ROS production and enhancing ER stress-mediated autophagy. Journal of Cellular Physiology. 10.1002/jcp.28395 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Fig. S1. Kinetics of GRP78 and ATF4 induction in MEFs following serum stimulation. A. MEFs were cultured in serum-free medium for 48 hours, and then stimulated with serum for the indicated time. Cell lysates were analyzed by immunoblot for AKT activation (p-AKT), AKT, GRP78 and ATF4 levels with β-actin serving as loading control. B. Same as in panel A but Grp78 mRNA was analyzed by RT-PCR with β-actin mRNA serving as loading control. C. Quantitation of the induction profile for the indicated proteins and mRNA shown in panel A and B.