Abstract

Cardiac MRI of small animal models of cancer radiation therapy (RT) is a valuable tool for studying the effect of RT on the heart. However, standard cardiac MRI exams require long scanning times, which is challenging for sick animals that may not survive extended periods of imaging under anesthesia. The purpose of this study is to develop an optimized, fast MRI exam for comprehensive cardiac functional imaging of small-animal models of cancer RT. Ten adult female rats (2 non-irradiated and 8 irradiated) were scanned using the developed exam. Optimal imaging parameters were determined, which minimized scanning time while ensuring measurement accuracy and avoiding imaging artifacts. This optimized, fast MRI exam lasted for 30 minutes, which was tolerated by all animals. EF was normal in all imaged rats, although it was significantly increased in the irradiated rats, which also showed ventricular hypertrophy. However, myocardial strain was significantly reduced in the irradiated rats. In conclusion, a fast MRI exam has been developed for comprehensive cardiac functional imaging of rats in 30 minutes, with optimized imaging parameters to ensure accurate measurements and tolerance by irradiated rats. The generated strain measurements provide an early marker of regional cardiac dysfunction before global function is affected.

Keywords: Radiation therapy, small animal model, heart, cardiac function, strain

1. Introduction

Radiation therapy (RT) is used by more than 50% of all cancer patients. However, RT for cancers in the thorax resulting in incidental cardiac RT exposure can have significant adverse effects on the heart. For example, RT-induced cardiotoxicity can be as high as 33% in lung cancer [1–5]. The most common initial feature of cardiotoxicity is asymptomatic cardiac dysfunction, which, if left untreated, may progress to heart failure (HF) [6, 7]. The current clinical standard for evaluating the heart health in cancer patients is measuring ventricular ejection fraction (EF), where an EF >50% is considered normal [8]. However, EF may not reveal regional cardiac dysfunction following RT due to the heart’s compensatory mechanism to maintain normal EF in the face of abnormal regional heart contractility [9–11]. Recently, a considerable body of literature has illustrated the importance of myocardial strain imaging for detecting early development of subclinical regional cardiac dysfunction in different cardiovascular diseases [9, 12–15]. Therefore, an optimal cardiac imaging protocol should include sequences for imaging both global and regional heart functions.

Small-animal imaging is essential for better understanding of cardiac dysfunction development, as animal models of different cardiovascular diseases can be studied under controlled conditions and the imaging results compared to histology findings [16, 17]. The knowledge gained from these preclinical experiments are valuable to help transfer treatments and interventions from bench to bed side. Furthermore, the capability of longitudinally monitoring the progression or remission of heart disease in the same animal allows for efficient and cost-effective use of animal models. Here we focused on developing a platform to image regional cardiac dysfunction in a rat model of localized cardiac radiation.

MRI is considered the gold standard for evaluation of cardiac function [18–20]. Nevertheless, small-animal cardiac MRI [16, 17] is more challenging than human imaging due to the animal’s small heart size and rapid heart rate (>300 bpm for rats), which pose technical challenges [21, 22]. Therefore, specialized small-animal MRI scanners have ultrahigh magnetic field strength (>7T) and are equipped with powerful gradient systems and preclinical specific radiofrequency (RF) coils to ensure adequate performance. Furthermore, multiple signal averages are typically acquired to increase signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) and maintain high spatial and temporal resolutions, albeit at the cost of lengthy scan times. Such long MRI scans are challenging for small animal models, as after high dose RT to the heart they can be compromised with deteriorated cardiac function and inconsistent breathing pattern, and therefore, they may not survive extended periods of imaging under anesthesia. In this study, we developed an optimized, fast MRI exam for evaluating both global and regional cardiac functions in a rat model of RT and investigated the effects of different imaging parameters on image quality and cardiac measurements accuracy.

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Experimental Design

This animal study was approved by Instructional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) at our institution. Adult salt-sensitive (SS) female rats (Medical College of Wisconsin, n=10: 8 irradiated and 2 sham-treated controls) were prospectively scanned on a 9.4T small-animal MRI scanner with 30-cm bore diameter (Bruker, Ettlingen, Germany) between September 2018 and June 2019. The irradiated rats received image-guided, localized, whole-heart radiation to 24 Gy using 3 equally weighted fields with the high-precision image-guided X-RAD SmART irradiator (Precision X-Ray, North Branford, CT), as previously described [23]. Rats were imaged at 8 weeks post radiation when their age was ~20 weeks. A 4-element surface coil was used for signal receiving, which results in better image quality in cardiac imaging compared to volume coils. Rats were scanned in the prone position, with the heart at the center of the coil. Rats were imaged under continuous delivery of anesthesia via a nose cone with isoflurane, adjusted so the respiratory rate ranged from 40 and 60 cycles per minute during the scan. The electrocardiogram (ECG) signal, respiratory rate, and temperature were monitored during the scan using a remote monitoring system (Model 1025, SA Instruments Inc., Stony Brook, NY, USA). Prospective ECG gating was used with a 10–20 ms delay placed at the end of the acquisition time to accommodate for heart rate variation during the scan. Blanking time (the time during which the R-wave can be detected) was set manually to ~5 ms longer than total acquisition time (= repetition time (TR) × number of cardiac phases) to eliminate false ECG triggers.

2.2. Cardiac Functional MRI Exam

The MRI exam started with scouting sequences to obtain standard short-axis (SAX) and 4-chamber (4CH) planes. The scouting sequences were run without ECG or respiratory gating to minimize scan time. Although image quality was compromised by cardiac and respiratory motions, the resulting scouting images showed sufficient anatomical details for proper prescription of the SAX and 4CH planes.

A series of flow-compensated fast low-angle shot (FLASH) cine sequences were then run with both ECG and respiratory gating to acquire a 4CH and a stack of SAX slices covering the heart. Four flow-compensated FLASH tagging sequences were then run with both ECG and respiratory gating to acquire a 4CH and three (basal, mid-ventricular, and apical) SAX-tagged slices. Total MRI exam duration was (mean ± standard deviation) 30±2 minutes.

2.3. Imaging Parameters

The effects of changing the following parameters on cine image quality and measured EF were examined: number of averages, flip angle, matrix size, slice thickness, fat saturation, and repetition time (TR), as shown in Table 1 Optimal cine imaging parameters were as follows (Table 2): TR = 7 ms, echo time (TE) = 2.1 ms, flip angle = 15°, matrix = 176x176, field-of-view (FOV) = 40x40 mm2, slice thickness = 1 mm, acquisition bandwidth = 526 Hz/pixel, number of averages = 2, number of cardiac phases = 20, and scan time ~2 minutes/slice, depending on heart rate and breathing pattern.

Table 1.

Imaging parameters affecting cardiac function measurements

| Parameter | Examined Range | Effect |

|---|---|---|

| # Signal averages | 1 – 3 | SNR |

| Flip angle | 5° – 40° | CNR |

| Matrix | 86x86 – 300 x300 | Resolution |

| TR | 7ms – 15ms | Tissue contrast & artifacts |

| Slice thickness | 1mm – 3mm | Partial volume averaging |

| FOV | 12mm – 40mm | Aliasing |

| Fat saturation | Off, On | Fat signal removal |

| Tag separation | 0.5mm – 2mm | Tags density |

| Tag width | 0.1mm – 0.5mm | Tags resolution |

Abbreviations: CNR, contrast-to-noise ratio; FOV, field of view; SNR, signal-to-noise ratio; TR, repetition time.

Table 2.

Optimal imaging parameters for cine and tagging MRI sequences for small-animal imaging

| Parameter | Cine | Tagging |

|---|---|---|

| Pulse Sequence | Flow-compensated FLASH | Flow-compensated FLASH |

| TR | 7 ms | 7 ms |

| TE | 2.1 ms | 2.5 ms |

| FOV | 40 mm | 40 mm |

| Matrix | 176x176 | 256x256 |

| Slice thickness | 1 mm | 1 mm |

| # Averages | 2 | 3 |

| Flip angle | 15° | 15° |

| Bandwidth | 526 Hz/pixel | 376 Hz/pixel |

| Tag Separation | -- | 1 mm |

| Tag width | -- | 0.1 mm |

Abbreviations: FLASH, fast low-angle shot; FOV, field of view; TE, echo time; TR, repetition time.

The effects of changing the following parameters on tagged image quality and measured myocardial strain were examined: number of averages, tagline width, and tag separation, as shown in Table 1. Optimal tagging imaging parameters were as follows (Table 2): TR = 7 ms, TE = 2.5 ms, flip angle = 15°, matrix = 256x256, FOV = 40x40 mm2, slice thickness = 1 mm, acquisition bandwidth = 375 Hz/pixel, number of averages = 3, number of cardiac phases = 20, and scan time ~4 minutes/slice.

2.4. Image Analysis

The images were analyzed by an imaging specialist with 17 years of experience in cardiac MRI, who was unaware of the animal type (irradiated versus non-irradiated) at the time of image analysis. The cine images were analyzed using cvi42 software (Circle, Calgary, Canada) to calculate left ventricular EF and mass as measure of global cardiac function. The tagged images were analyzed using the harmonic phase (HARP) technique [24] to calculate different myocardial strain components as measures of regional cardiac function. The measurements were represented as mean ± standard deviation (SD). Student’s t-tests were conducted to identify significant differences in EF and strain measurements between irradiated and non-irradiated rats (P <0.05 was considered significant).

3. Results

3.1. Results from Irradiated and Non-Irradiated Rats

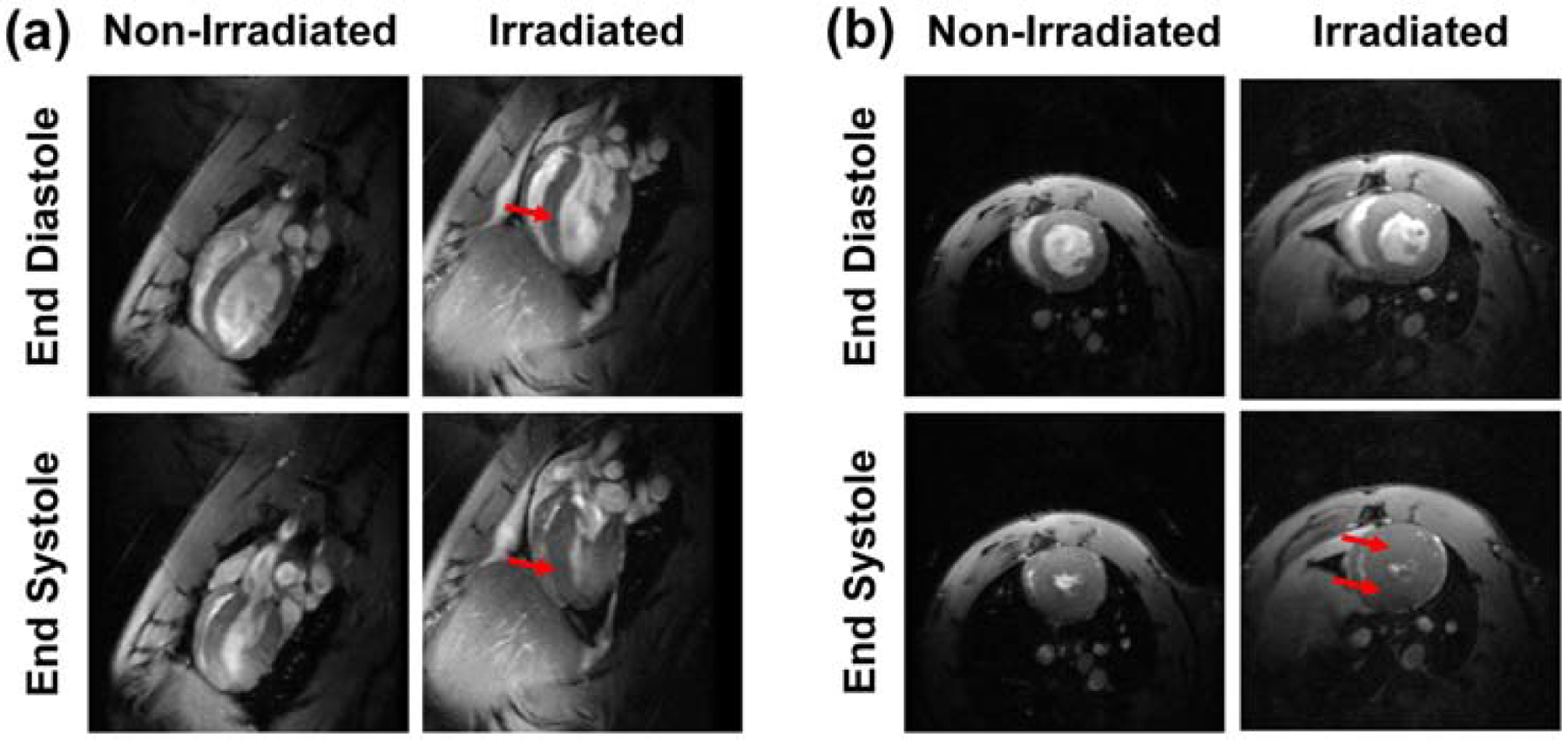

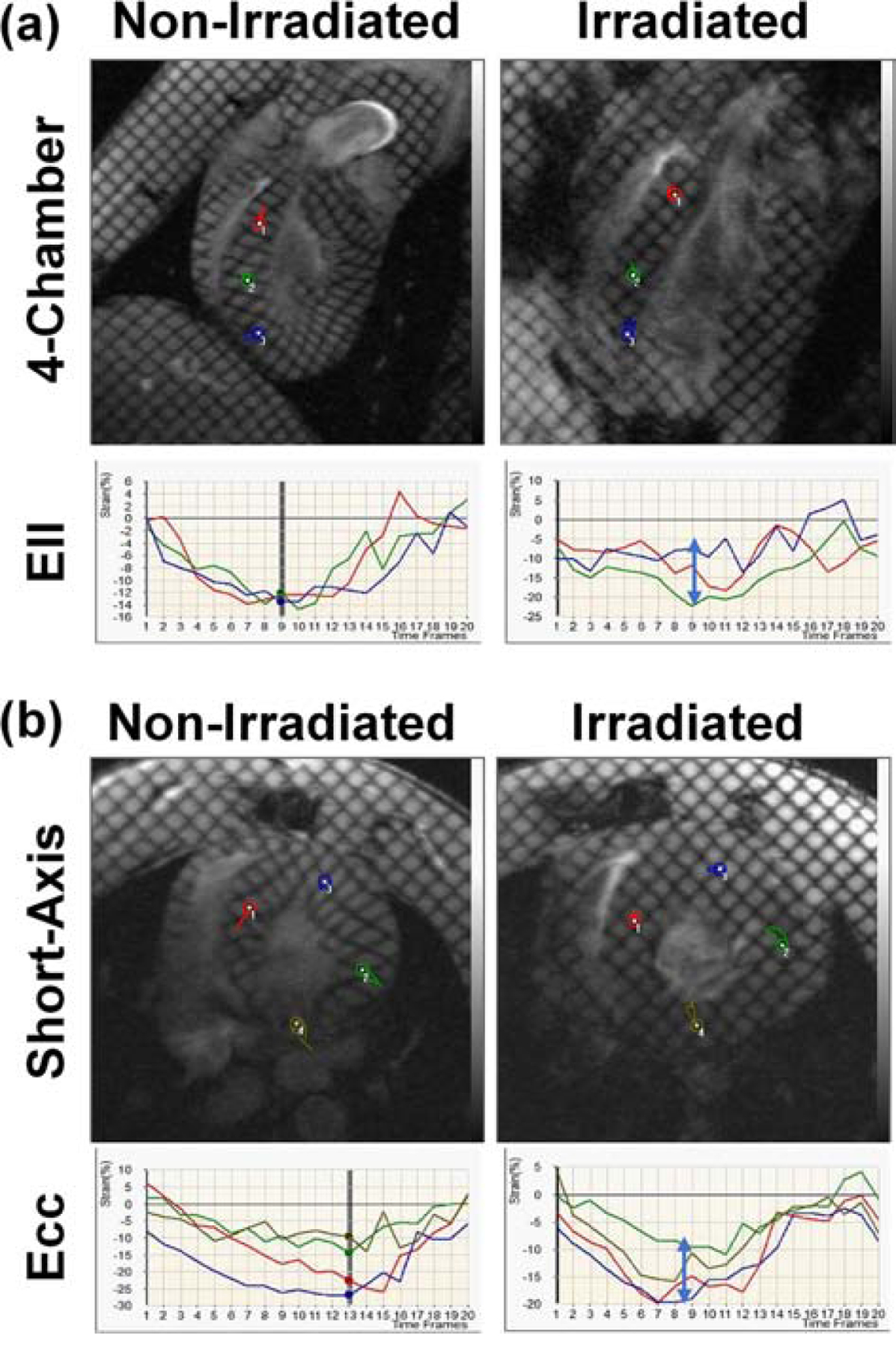

MRI scans were successfully completed in all rats. Representative cine and tagged images of irradiated and non-irradiated rats acquired with optimal imaging parameters are shown in Figure 1 and Figure 2, respectively, where irradiated rats showed ventricular remodeling and hypertrophy and the non-irradiated rats did not. Global heart function was normal in all animals; however, the irradiated rats showed reduced strain measurements (Table 3). Although EF was normal in all rats, it was significantly increased in the irradiated (EF = 78.6±2.6%) compared to non-irradiated (EF = 60±1.2%) rats (P<0.001). The irradiated rats also showed ventricular hypertrophy (mass = 0.52±0.05 g) compared to non-irradiated rats (mass = 0.39±0.05 g, P<0.05, Table 3). However, longitudinal, radial, and circumferential strains were reduced in the irradiated (−14.1±1.5%, 43.1±10.2%, −9.8±2.4%) compared to non-irradiated (−18±1.4%, 61.5±16.3%, −12.5±0.7%) rats with significant difference between irradiated and non-irradiated rats (P<0.05, Table 3).

Figure. 1. Cine images of non-irradiated and irradiated rats showing ventricular remodeling post irradiation.

(a) Four-chamber and (b) short-axis cine images at end-diastole (top) and end-systole (bottom) of non-irradiated (left) and irradiated (right) rats acquired with fast low-angle shot (FLASH) cine sequence. The images show ventricular remodeling, as illustrated by change in the ventricular shape (arrows in the 4-chamber images), to maintain global heart function. Note increased hypertrophy post irradiation (arrows in the short-axis images).

Figure 2. Tagged images of non-irradiated and irradiated rats showing irradiation’s effect on myocardial strain.

(a) Four-chamber and (b) short-axis tagged images of non-irradiated (left) and irradiated (right) rats, along with the generated longitudinal (Ell) and circumferential (Ecc) strain curves at different locations in the heart (color probes in the tagged images). Note reduced strain post irradiation (vertical blue arrows). Images acquired using fast low-angle shot (FLASH) tagging sequence.

Table 3.

Global and regional cardiac function results (mean±SD) in studied rats

| Measurement | Non-irradiated | Irradiated |

|---|---|---|

| EF (%) | 60±1.2 | 78.6±2.6 |

| Mass (g) | 0.39±0.05 | 0.52±0.05 |

| Ecc (%) | −18±1.4 | −14.1±1.5 |

| Err (%) | 61.5±16.3 | 43.1±10.2 |

| Ell (%) | −12.5±0.7 | −9.8±2.4 |

Abbreviations: EF = ejection fraction. Ecc, Err, Ell = circumferential, radial, and longitudinal strains, respectively.

3.2. Imaging Parameters Affecting EF Measurements

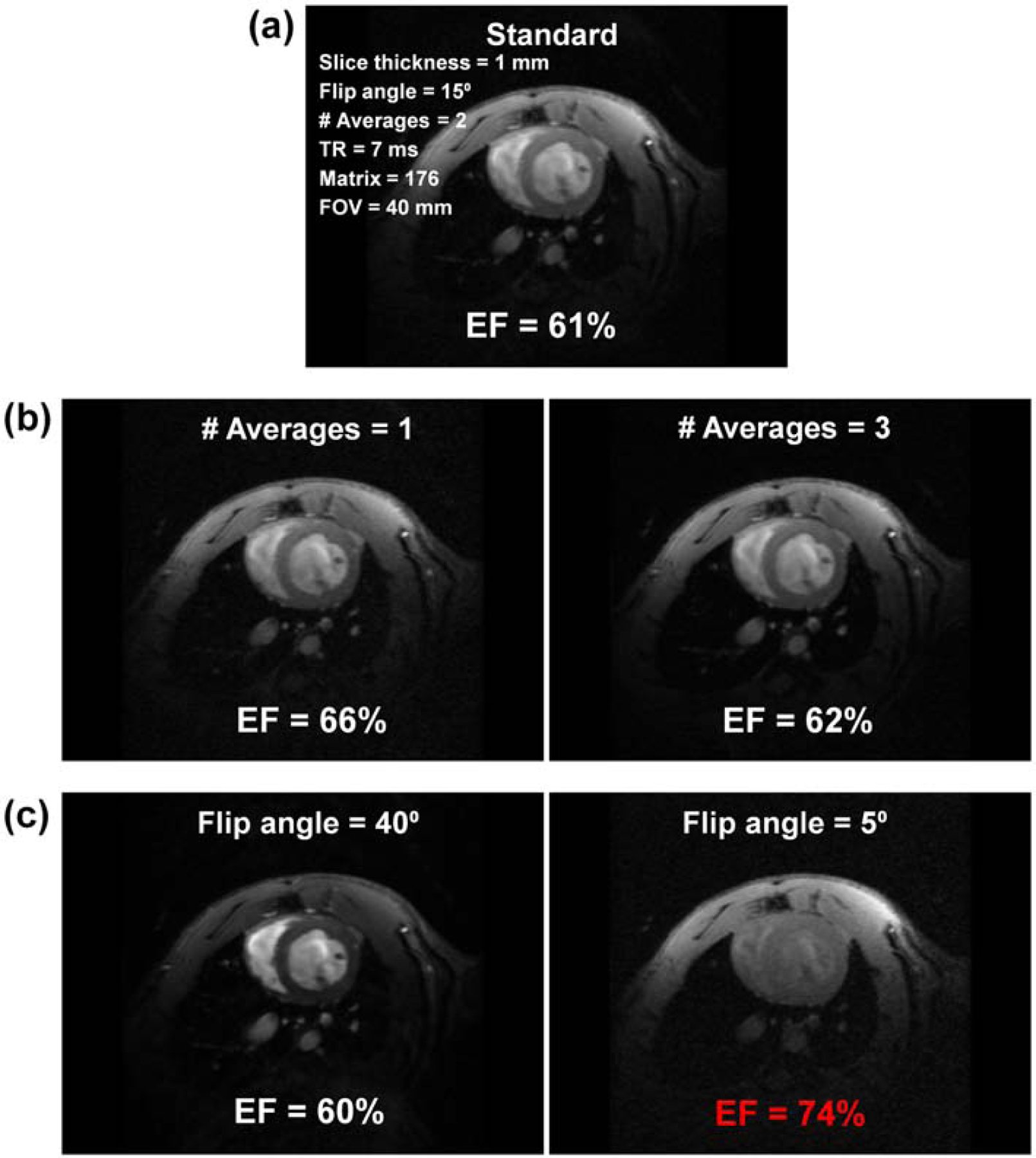

Cine imaging acquired with optimal imaging parameters, and the effects of changing SNR and blood-to-myocardium contrast-to-noise ratio (CNR) on EF measurements are illustrated in Figure 3. Reducing or increasing SNR by up to 50% did not significantly affect image quality or measured EF. Reducing the number of averages from 2 (optimal value) to 1 resulted in ≤5% change in EF, while increasing the number of averages from 2 to 3 resulted in ≤1% change in EF. Increasing the flip angle resulted in improved blood-to-myocardium CNR at the cost of reduced SNR. Increasing the flip angle from 15° (optimal value) up to 40° resulted in ≤1% change in EF, while reducing the flip angle resulted in decreased CNR such that EF changed by >10% at flip angle of 5°.

Figure 3. The effects of SNR and CNR on EF measurements.

(a) Standard short-axis cine image acquired with optimal imaging parameters (EF = 61% in this case). (b) Reducing (left) and increasing (right) number of averages from 2 (optimal value) to 1 and 3 results in 50% reduction and 50% increase in SNR, respectively, with resulting small (EF = 66%) and minimal (EF = 62%) changes in EF measurement, respectively. (c) Increasing (left) and decreasing (right) the flip angle from 15° (optimal value) to 40° and 5° increases and significantly decreases blood-to-myocardium CNR, respectively, with minimal (EF = 60%) and significant (EF = 74%; incorrect value in red font) changes in EF measurement, respectively. CNR, contrast-to-noise ratio; EF, ejection fraction; SNR = signal-to-noise ratio.

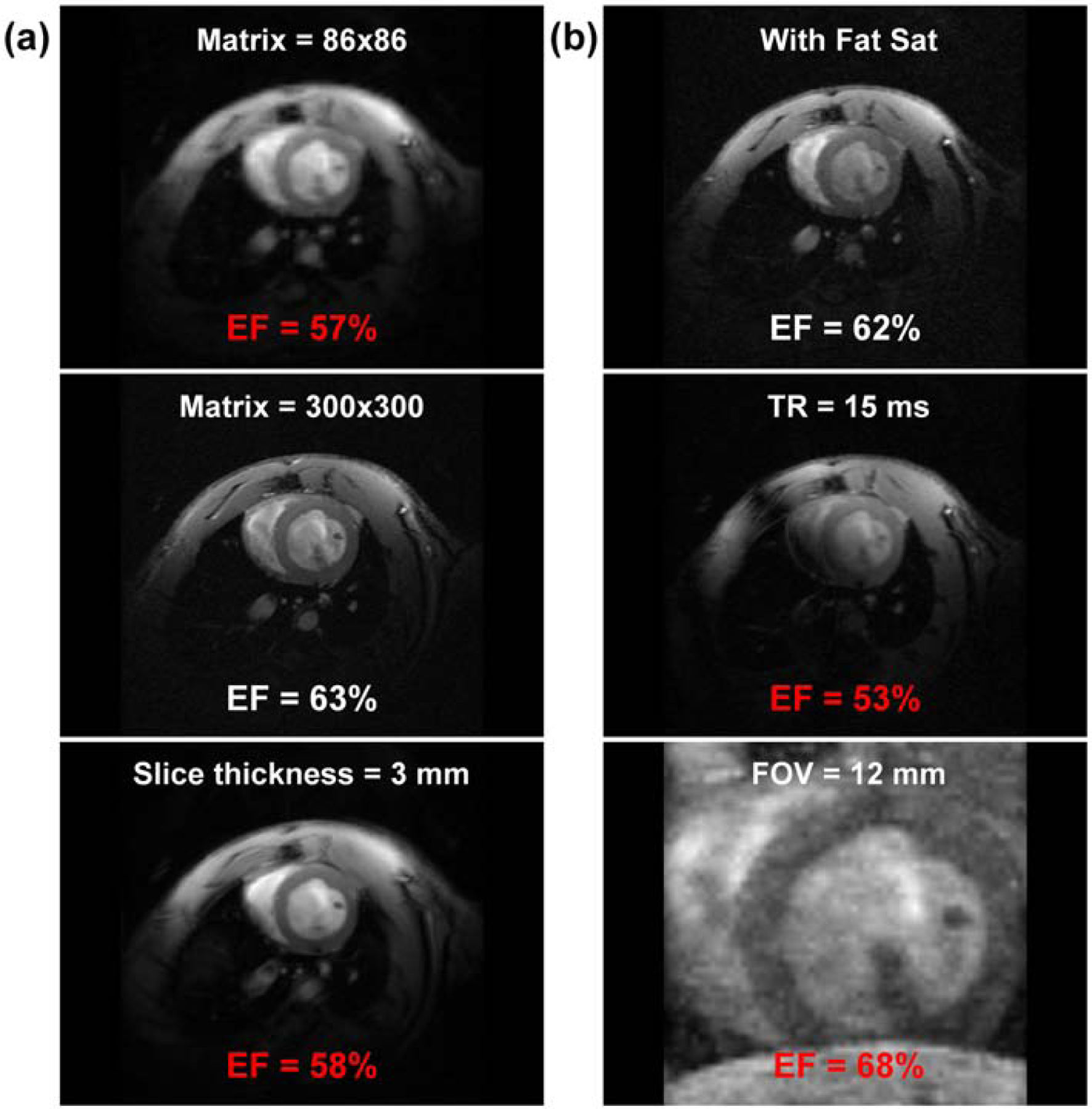

The effects of partial volume averaging, fat saturation, and image artifacts on image quality and FE are illustrated in Figure 4. Reducing the matrix size in half (from 176x176 (optimal value) to 86x86) resulted in EF underestimation by 4–5%, while increasing the matrix size beyond 176x176 resulted in ≤1% change in EF. Increasing the slice thickness from 1 mm (optimal value) to 3 mm resulted in partial volume effect and EF underestimation by 3–4%. Using fat saturation feature slightly affected image quality, but EF did not change. Increasing TR from 7 ms (optimal value) to >10 ms resulted in signal inhomogeneity artifacts and significant change (up to 10%) in EF. Reducing FOV resulted in wrap-around artifacts that affected EF depending on artifact severity.

Figure 4. The effects of partial-volume averaging, fat saturation, and image artifacts on EF measurement.

Cine image acquire with optimal parameters is shown in Figure 3(a), where EF = 61% in this case. (a) Reducing matrix size from 176x176 (optimal value) to 86x86 (top) and increasing it to 300x300 (middle) result in partial volume averaging and increased resolution, respectively, with significant (EF = 57%; incorrect value in red font) and slight (EF = 63%) changes in EF measurement, respectively. Increasing slice-thickness from 1 mm (optimal value) to 3 mm (bottom) results in partial volume averaging, and EF decreases to 58% (red font). (b) Adding fat-saturation option (top) slightly affects SNR, but results in correct EF (=62%). Doubling TR from 7 ms (optimal value) to 15 ms (middle) results in signal inhomogeneity artifacts, which significantly affects EF (=53%; red font). Reducing FOV (bottom) results in wrap-around aliasing artifacts and incorrect EF (=68%; red font). EF, ejection fraction; FOV, field of view; SNR, signal-to-noise ratio; TR, repetition time.

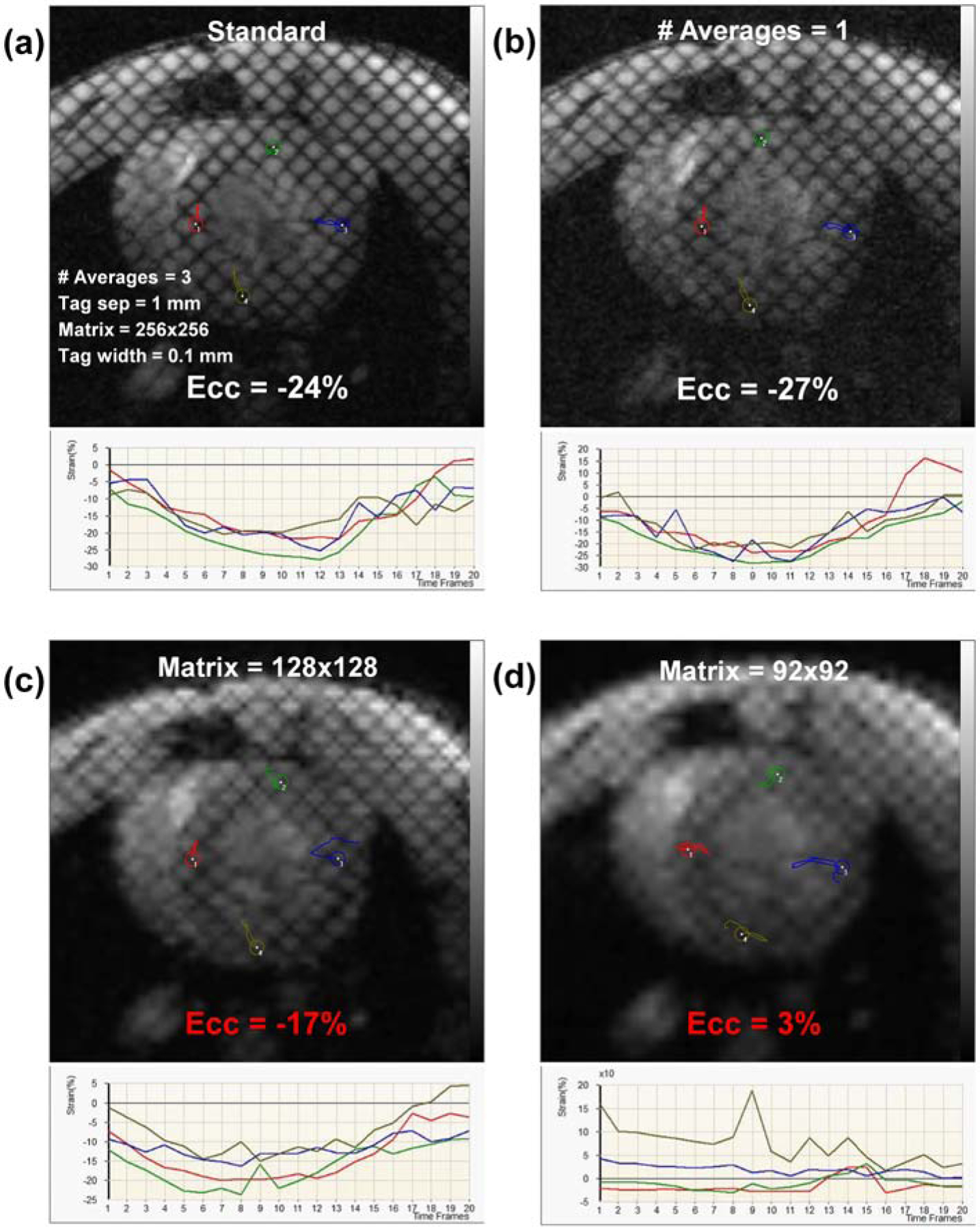

3.3. Imaging Parameters Affecting Strain Measurements

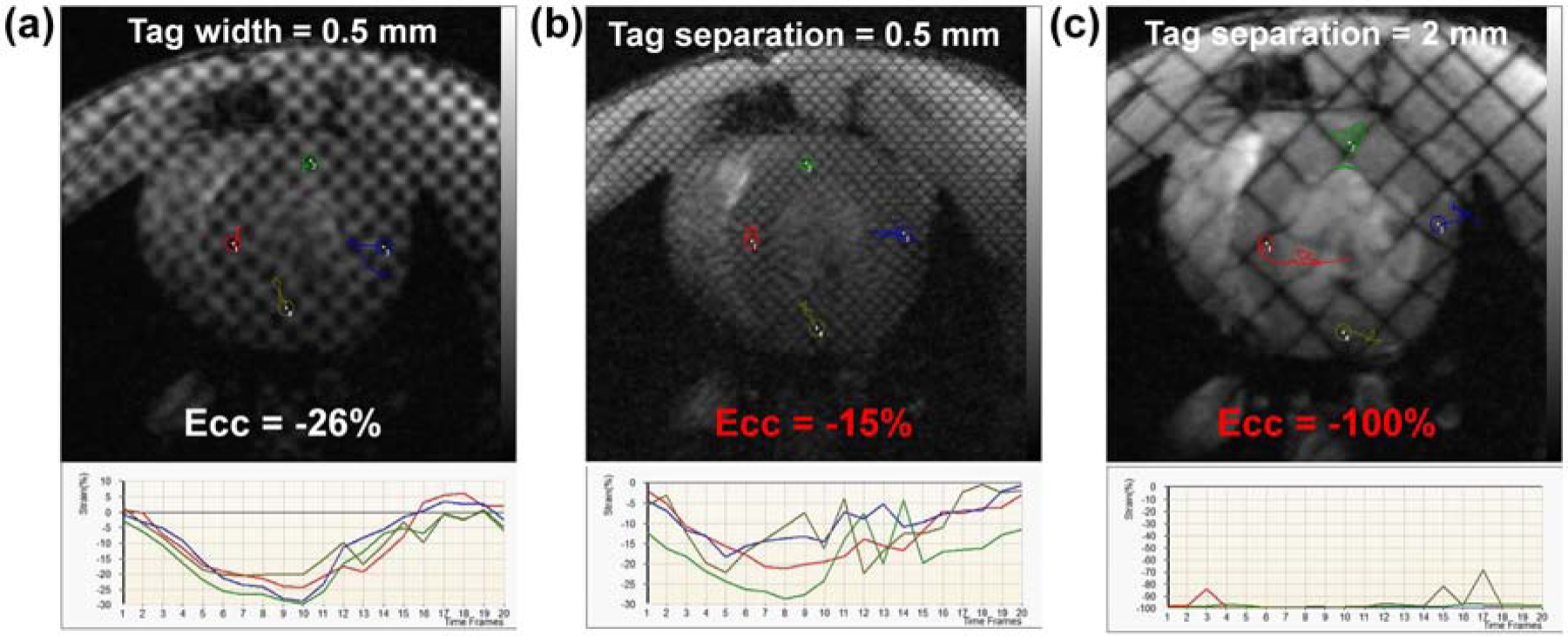

Tagged image acquired with optimal imaging parameters, and the effects of changing SNR and resolution on strain measurements are illustrated in Figure 5. Reducing number of averages below 3 (the optimal value) resulted in 2–3% change in strain measurements. Reducing image resolution in half (changing matrix from 256x256 (optimal value) to 128x128) resulted in significant (7–10%) change in strain measurements, while further reduction in resolution resulted in unrealistic strain values. Figure 6 shows the effects of the changing the tagging profile on strain. Increasing the tagline width to 50% of the tag separation resulted in ≤2% change in strain measurements. Doubling the tagline density (reducing tag separation from optimal value of 1 mm to 0.5 mm) resulted in blurred tags and up to 10% change in strain measurements, while increasing the tag separation to 2 mm resulted in significant change in the results, such that unrealistic strain values were obtained when only one tagline appeared across the myocardial wall thickness.

Figure 5. The effects of SNR and resolution on strain measurements.

(a) Short-axis tagged image acquired with optimal imaging parameters (shown on the image) and the resulting strain curves of different colored probes in the figure, where average peak circumferential strain (Ecc) in this case = −24% (correct value). (b) Reducing number of averages results in SNR reduction, but has small effect on strain measurement (Ecc = −27%). (c) Reducing spatial resolution in half (changing matrix size from 256x256 (optimal value) to 128x128) results in significant decrease in strain measurement (Ecc = −17%; incorrect value in red font). (d) Any further decrease in spatial resolution (matrix size reduced to 92x92) results in unrealistic strain measurements (Ecc = 3%; red font). SNR, signal-to-noise ratio.

Figure 6. The effects of changing the tagging profile on strain measurements.

Short-axis tagged image obtained with optimal imaging parameters is shown in Figure 5(a), where correct circumferential strain, Ecc = −24% (a) Increasing the width of the taglines from 0.1 mm (optimal value) to 0.5 mm (half of the tag separation value of 1 mm) has small effect on strain measurements (Ecc changes from −24% to −26%). (b) Doubling tagline density (tag separation is reduced from 1 mm (optimal value) to 0.5 mm) results in blurry taglines, which significantly affects strain measurement (Ecc changes from −24% to −15%; incorrect value in red font). (c) Reducing tag density in half (tag separation is increased from 1 mm (optimal value) to 2 mm) results in sparse taglines across the myocardium, such that strain analysis results in unrealistic strain measurement, Ecc = −100% (red font).

4. Discussion

In this study, we investigated the effects of different imaging parameters on the accuracy of different MRI-generated cardiac functional parameters, based upon which we developed and evaluated an optimized, fast MRI protocol for comprehensive cardiac functional imaging in small animals. The developed protocol was tolerated by the irradiated rats with compromised cardiopulmonary function due to cardiac radiation exposure, and the MRI protocol demonstrated the capability for revealing early signs of regional cardiac dysfunction post-radiation.

In this study, the EF revealed normal global function in all animals, with paradoxically increased EF in the irradiated rats, which is likely as a result of ventricular remodeling and the compensatory mechanism of the heart in the face acute injury post-radiation. However, strain measurements were reduced in the irradiated compared to non-irradiated rats, which demonstrates the capability of strain imaging for early detection of radiation-induced subclinical cardiac dysfunction before global cardiac function is affected. It should be noted that the resulting increase in EF despite the decrease in all strain components can be understood in terms of undergoing ventricular remodeling through hypertrophy and increase in myocardial mass post-RT as a compensatory mechanism in face of acute radiation injury. Although this may be associated with increase in myocardial tissue displacement, especially in the radial direction as a result of myocardial muscle build-up, tissue contractility, represented by radial strain, was reduced compared to control cases, which we have previously reported by echocardiography in the same animal model [23].

In this study, we focused on evaluating the effects of different imaging parameters on global and regional cardiac function measurements in a RT rat model. The results showed that reduced blood-to-myocardium CNR (e.g. when the flip angle was reduced to 5°) and the presence of imaging artifacts (e.g. when TR was increased to >10 ms) in the cine images significantly affected EF measurements, whereas image resolution had less effect on EF. On the other hand, reduced resolution (e.g. when the matrix size was cut in half) in the tagged images had a significant effect on strain measurements, whereas the tagline density had less effect on measured strain as long as sufficient image resolution was maintained (i.e. when tagline density was neither too high to cause image blurring nor too low such that only one tagline appeared across the myocardial wall thickness). Based on these results, the cine and tagging sequences were optimized to ensure accurate cardiac functional measurements while minimizing scan time.

Although this study focused on optimizing an MRI scan for cardiac functional imaging in small animals, which may limit direct translational potential of the presented data, the developed protocol provides an efficient means for obtaining sensitive markers of cardiac dysfunction in small-animal models of RT, which can lead to better understanding of the mechanism of RT-induced cardiotoxicity development, determination of regional radiation sensitivity of different cardiac substructures, and ultimately better guidelines for RT planning to minimize cardiotoxicity with potential translational value. In this study, we used conventional MRI tagging for strain imaging. However, it should be noted that other advanced MRI techniques, e.g. strain-encoding (SENC), displacement-encoding with stimulated echo (DENSE), and feature tracking, could be used for strain imaging [25]. These techniques provide additional features, for example, the capability of measuring through-plane strain in one heartbeat with SENC, high-sensitivity strain measurement from the phase-encoded DENSE images, and using conventional cine images for measuring strain without the need for additional imaging sequences, as in MRI feature tracking. In this regard, the reader is referred to recent studies demonstrating the implementation of advanced strain imaging techniques and their clinical value for early detection of HF development [26–29].

Here, we show the capability of strain imaging by MRI for early detection of cardiac dysfunction as early as 8 weeks post-irradiation in rats. However, it should be noted that late cardiotoxicity effects have been reported where RT-induced cardiac complications could emerge even years after treatment [1, 2]. Therefore, from a clinical point of view, an optimized, fast MRI exam that provides sensitive measures of cardiac function, e.g. regional myocardial strain, would be valuable and cost-effective for periodic patient follow-up to allow for early detection of subclinical cardiac dysfunction and prompt intervention to avoid HF development with associated morbidity, mortality, and expensive healthcare costs.

One limitation of the current study is that the developed protocol did not include sequences for evaluating other cardiac parameters besides the heart function, e.g. myocardial tissue characterization [30]. Nevertheless, adding such sequences to the MRI exam would result in doubling the scan time, which may not then be tolerable by sick irradiated rats. As myocardial strain is a promising marker of subclinical cardiac dysfunction before clinical measures are affected [9, 12–15], the developed fast scan is expected to provide useful information for early detection of radiation-induced regional cardiac dysfunction, as demonstrated by our results. Another limitation of the current study is the small number of studied animals, which did not allow for conducting thorough statistical analysis. Nevertheless, even with limited number of control animals, the results showed significant differences in global and regional cardiac function measurements between irradiated and control animals. While the goal of this study was to show a proof-of-concept of the capability of a fast MRI exam for comprehensive cardiac function imaging with potential for illustrating changes in cardiac functional measures post-radiation, additional larger studies using the developed MRI exam are warranted for better understanding of RT-induced cardiotoxicity, as well as the effects of different factors, e.g. genetic profile, on cardiac function post-RT, with potential clinical translational value of such studies.

5. Conclusions

This study provided an optimized, fast MRI protocol for comprehensive cardiac functional imaging in small animals. The study revealed the effect of different imaging parameters on cardiac measurements’ accuracy, as well as optimal imaging parameter settings to ensure accurate cardiac measurements while minimizing scan time to be tolerable by sick irradiated animals. The developed optimized exam will be valuable for better understanding of early subclinical cardiac dysfunction development post-RT before global cardiac function is affected, with potential clinical translational value to reduce RT-induced cardiotoxicity in cancer patients.

Highlights.

An optimized MRI exam is developed for cardiac functional imaging of small animals.

MRI imaging parameters were optimized to eliminate artifacts and reduce scan time.

The developed fast MRI exam was tolerated by all sick irradiated animals.

Ejection fraction was paradoxically increased in the irradiated rats.

MRI strain imaging allowed for early detection of regional cardiac dysfunction.

Acknowledgment

This work was supported by the Daniel M. Soref Charitable Trust, Center for Imaging Research, Medical College of Wisconsin, USA (E.H.I. and C.B.). This work was supported by NIH NHLBI 1R01HL147884, Bethesda, Maryland, USA (C.B.). Additional support was provided by the Mary Kay Foundation Award Grant No. 017-29, Dallas, Texas, USA (C.B.), Susan G. Komen® Grant CCR17483233, Dallas, Texas, USA (C.B.), the Nancy Laning Sobczak, PhD, Breast Cancer Research Award (C.B.), Milwaukee, Wisconsin, USA, the Medical College of Wisconsin Cancer Center, Milwaukee, Wisconsin, USA (C.B.), the Michael H. Keelan, Jr., MD, Research Foundation Grant (C.B.), Milwaukee, Wisconsin, USA, and the Cardiovascular Center at the Medical College of Wisconsin, Milwaukee, Wisconsin, USA (C.B.).

Footnotes

Declarations of interest: The authors have no relevant disclosures/conflict of interest to declare. C.B. received research funding from Innovation Pathways, Palo Alto, CA, ending in February 2020.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- [1].Hardy D, Liu CC, Cormier JN, Xia R, Du XL. Cardiac toxicity in association with chemotherapy and radiation therapy in a large cohort of older patients with non-small-cell lung cancer. Ann Oncol 2010;21(9):1825–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Haque W, Verma V, Fakhreddine M, Butler EB, Teh BS, Simone CB 2nd Trends in Cardiac Mortality in Patients With Locally Advanced Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2018;100(2):470–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Lally BE, Detterbeck FC, Geiger AM, Thomas CR Jr., Machtay M, Miller AA, et al. The risk of death from heart disease in patients with nonsmall cell lung cancer who receive postoperative radiotherapy: analysis of the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results database. Cancer 2007;110(4):911–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Dikshit R, Eser S, Mathers C, Rebelo M, et al. Cancer incidence and mortality worldwide: sources, methods and major patterns in GLOBOCAN 2012. Int J Cancer 2015;136(5):E359–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Verma V, Fakhreddine MH, Haque W, Butler EB, Teh BS, Simone CB 2nd Cardiac mortality in limited-stage small cell lung cancer. Radiother Oncol 2018. [DOI] [PubMed]

- [6].Johnson CB, Sulpher J, Stadnick E. Evaluation, prevention and management of cancer therapy-induced cardiotoxicity: a contemporary approach for clinicians. Curr Opin Cardiol 2015;30(2):197–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Higgins AY, O’Halloran TD, Chang JD. Chemotherapy-induced cardiomyopathy. Heart Fail Rev 2015;20(6):721–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Yu AF, Ky B. Roadmap for biomarkers of cancer therapy cardiotoxicity. Heart 2016;102(6):425–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Kongbundansuk S, Hundley WG. Noninvasive imaging of cardiovascular injury related to the treatment of cancer. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging 2014;7(8):824–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Khouri MG, Klein MR, Velazquez EJ, Jones LW. Current and emerging modalities for detection of cardiotoxicity in cardio-oncology. Future Cardiol 2015;11(4):471–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Cross MJ, Berridge BR, Clements PJ, Cove-Smith L, Force TL, Hoffmann P, et al. Physiological, pharmacological and toxicological considerations of drug-induced structural cardiac injury. Br J Pharmacol 2015;172(4):957–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Choi EY, Rosen BD, Fernandes VR, Yan RT, Yoneyama K, Donekal S, et al. Prognostic value of myocardial circumferential strain for incident heart failure and cardiovascular events in asymptomatic individuals: the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis. Eur Heart J 2013;34(30):2354–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Wong DT, Leong DP, Weightman MJ, Richardson JD, Dundon BK, Psaltis PJ, et al. Magnetic resonance-derived circumferential strain provides a superior and incremental assessment of improvement in contractile function in patients early after ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. Eur Radiol 2014;24(6):1219–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Toro-Salazar OH, Gillan E, O’Loughlin MT, Burke GS, Ferranti J, Stainsby J, et al. Occult cardiotoxicity in childhood cancer survivors exposed to anthracycline therapy. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging 2013;6(6):873–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Venkatesh BA, Donekal S, Yoneyama K, Wu C, Fernandes VR, Rosen BD, et al. Regional myocardial functional patterns: Quantitative tagged magnetic resonance imaging in an adult population free of cardiovascular risk factors: The multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis (MESA). J Magn Reson Imaging 2015;42(1):153–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Hoyer C, Gass N, Weber-Fahr W, Sartorius A. Advantages and challenges of small animal magnetic resonance imaging as a translational tool. Neuropsychobiology 2014;69(4):187–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Nahrendorf M, Hiller KH, Hu K, Ertl G, Haase A, Bauer WR. Cardiac magnetic resonance imaging in small animal models of human heart failure. Med Image Anal 2003;7(3):369–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Salerno M, Sharif B, Arheden H, Kumar A, Axel L, Li D, et al. Recent Advances in Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance: Techniques and Applications. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging 2017;10(6). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Marwick TH, Neubauer S, Petersen SE. Use of cardiac magnetic resonance and echocardiography in population-based studies: why, where, and when? Circ Cardiovasc Imaging 2013;6(4):590–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Ibrahim el SH. Imaging sequences in cardiovascular magnetic resonance: current role, evolving applications, and technical challenges. Int J Cardiovasc Imaging 2012;28(8):2027–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Zhou R, Pickup S, Glickson JD, Scott CH, Ferrari VA. Assessment of global and regional myocardial function in the mouse using cine and tagged MRI. Magn Reson Med 2003;49(4):760–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Liu W, Ashford MW, Chen J, Watkins MP, Williams TA, Wickline SA, et al. MR tagging demonstrates quantitative differences in regional ventricular wall motion in mice, rats, and men. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 2006;291(5):H2515–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Schlaak RA, Frei A, Schottstaedt AM, Tsaih SW, Fish BL, Harmann L, et al. Mapping genetic modifiers of radiation-induced cardiotoxicity to rat chromosome 3. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 2019;316(6):H1267–H80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Osman NF, Kerwin WS, McVeigh ER, Prince JL. Cardiac motion tracking using CINE harmonic phase (HARP) magnetic resonance imaging. Magn Reson Med 1999;42(6):1048–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Ibrahim EH. Heart Mechanics: Magnetic Resonance Imaging Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- [26].Giusca S, Korosoglou G, Zieschang V, Stoiber L, Schnackenburg B, Stehning C, et al. Reproducibility study on myocardial strain assessment using fast-SENC cardiac magnetic resonance imaging. Sci Rep 2018;8(1):14100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Korosoglou G, Giusca S, Hofmann NP, Patel AR, Lapinskas T, Pieske B, et al. Strain-encoded magnetic resonance: a method for the assessment of myocardial deformation. ESC Heart Fail 2019;6(4):584–602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Bucius P, Erley J, Tanacli R, Zieschang V, Giusca S, Korosoglou G, et al. Comparison of feature tracking, fast-SENC, and myocardial tagging for global and segmental left ventricular strain. ESC Heart Fail 2020;7(2):523–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Kawaji K, Nazir N, Blair JA, Mor-Avi V, Besser S, Matsumoto K, et al. Quantitative detection of changes in regional wall motion using real time strain-encoded cardiovascular magnetic resonance. Magn Reson Imaging 2020;66:193–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Jordan JH, D’Agostino RB Jr., Hamilton CA, Vasu S, Hall ME, Kitzman DW, et al. Longitudinal assessment of concurrent changes in left ventricular ejection fraction and left ventricular myocardial tissue characteristics after administration of cardiotoxic chemotherapies using T1-weighted and T2-weighted cardiovascular magnetic resonance. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging 2014;7(6):872–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]