Abstract

BACKGROUND:

Post-transplant lymphoproliferative disorder (PTLD) is a life-threatening complication following lung transplant. We studied incidence and risk factors for PTLD in adult lung transplant recipients (LTRs) using the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation Registry.

METHODS:

The International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation Registry was used to identify adult, first-time, single and bilateral LTRs with at least 1 year of follow-up between 2006 and 2016. Kaplan–Meier method was used to describe the timing and distribution of PTLD. Univariable and multivariable Cox proportional hazards regression models were used to examine clinical characteristics associated with PTLD.

RESULTS:

Of 19,309 LTRs in the analysis cohort, we identified 454 cases of PTLD. Cumulative incidence of PTLD was 1.1% (95% CI = 1.0%–1.3%) at 1 year and 4.1% (95% CI = 3.6%–4.6%) at 10 years. Of the PTLD cases, 47.4% occurred within the first year following lung transplantation. In the multivariable model, independent risk factors for PTLD included age, Epstein–Barr virus serostatus, restrictive lung diseases, and induction. Risk of PTLD during the first year after transplant increased with increasing age in patients between 45 and 62 years at time of transplantation; the inverse was true for ages <45 years or >62 years. Finally, receiving a donor organ with human leukocyte antigen types A1 and A24 was associated with an increased risk of PTLD, whereas the recipient human leukocyte antigen type DR11 was associated with a decreased risk.

CONCLUSIONS:

Our study indicates that PTLD is a relatively rare complication among adult LTRs. We identified clinical characteristics that are associated with an increased risk of PTLD.

Keywords: lung transplant, PTLD, malignancy, Epstein-Barr virus, age, induction

Post-transplant lymphoproliferative disorder (PTLD) represents a serious complication following solid organ transplantation (SOT) and is associated with significant morbidity and mortality.1 After skin cancer, PTLD is the second most common malignancy following transplantation.2,3 The highest incidence of PTLD has been described in small intestine transplant recipients followed by lung and heart-lung recipients.2,4-6 Given the relative rare occurrence, there are few single-center studies analyzing incidence and risk factors associated with PTLD in adult lung transplant recipients (LTRs). Risk factors associated with PTLD in LTRs include Epstein–Barr virus (EBV) infection and donor/recipient EBV mismatch, cytomegalovirus (CMV) infection, cystic fibrosis, and aggressive immunosuppression.7-10 Less clear are risk factors associated with late cases of PTLD.11 A possible association has been also described between human leukocyte antigen (HLA) and PTLD.12,13 Several contradictory findings have been reported12,14-16; however, a dedicated analysis of this association in LTRs has not been published.

The aims of this study were to analyze the International Society for Heart and Lung transplant (ISHLT) Thoracic Organ Transplant Registry to describe the incidence of PTLD and identify pre- and peri-transplant clinical characteristics associated with PTLD in adult LTRs.

Methods

Study design

We analyzed the ISHLT Registry, an international longitudinal voluntary database that incorporates country and consortium transplant data reported by individual centers. A total of 260 lung transplant centers report to the ISHLT Registry, representing approximately 75% of the worldwide transplant activity.

Primary end-points and covariables

The primary end-point of interest was time to development of PTLD after lung transplantation. Outcomes were evaluated at time of yearly follow-up. Primary end-point was censored at last follow-up, patient death, or retransplant. We considered donor variables and recipient pre- and peri-transplant variables based on clinical relevance and reported associations with PTLD from prior studies. All covariables considered in the association analysis are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Summary of Pre- and Peri-Transplant Characteristics

| Patient characteristicsa | Overall(N = 19,309) |

Subjects with PTLD(N = 454) |

Subjects without PTLD(N = 18,855) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Summary measure | Missing | Summary measure | Missing | Summary measure | Missing | |

| Recipient age at transplant, years | 57 (47, 63) | 0 (0.00%) | 58 (45, 62) | 0 (0.00%) | 57 (47, 63) | 0 (0.00%) |

| Transplant procedure type | 0 (0.00%) | 0 (0.00%) | 0 (0.00%) | |||

| Single | 7,012 (36.31%) | 153 (33.70%) | 6,859 (36.38%) | |||

| Bilateral | 12,297 (63.69%) | 301 (66.30%) | 11,996 (63.62%) | |||

| Female | 8,320 (43.09%) | 0 (0.00%) | 173 (38.11%) | 0 (0.00%) | 8,147 (43.21%) | 0 (0.00%) |

| Total ischemia time left and right lung, hours | 4.9 (3.9, 6) | 1,101 (5.70%) | 4.92 (3.9, 6.2) | 40 (8.81%) | 4.9 (3.9, 6) | 1,061 (5.63%) |

| Type of induction at time of transplant | 204 (1.06%) | 21 (4.63%) | 183 (0.97%) | |||

| Cytolytic | 2,893 (14.98%) | 96 (21.15%) | 2,797 (14.83%) | |||

| Non-cytolytic | 7,650 (39.62%) | 135 (29.74%) | 7,515 (39.86%) | |||

| Both | 91 (0.47%) | 1 (0.22%) | 90 (0.48%) | |||

| No induction | 8,471 (43.87%) | 201 (44.27%) | 8,270 (43.86%) | |||

| Region of transplant center | 0 (0.00%) | 0 (0.00%) | 0 (0.00%) | |||

| North America | 19,083 (98.83%) | 435 (95.81%) | 18,648 (98.90%) | |||

| Europe | 11 (0.06%) | 7 (1.54%) | 4 (0.02%) | |||

| All others combined | 215 (1.11%) | 12 (2.64%) | 203 (1.08%) | |||

| ABO blood group | 1 (0.01%) | 0 (0.00%) | 1 (0.01%) | |||

| A | 7,785 (40.32%) | 191 (42.07%) | 7,594 (40.28%) | |||

| B | 2,147 (11.12%) | 56 (12.33%) | 2,091 (11.09%) | |||

| AB | 747 (3.87%) | 18 (3.96%) | 729 (3.87%) | |||

| O | 8,629 (44.69%) | 189 (41.63%) | 8,440 (44.76%) | |||

| Donor/recipient ABO match | 17,813 (92.25%) | 1 (0.01%) | 422 (92.95%) | 0 (0.00%) | 17,391 (92.24%) | 1 (0.01%) |

| Native lung disease | 10 (0.05%) | 0 (0.00%) | 10 (0.05%) | |||

| Cystic fibrosis | 2,633 (13.64%) | 90 (19.82%) | 2,543 (13.49%) | |||

| Obstructive | 7,707 (39.91%) | 146 (32.16%) | 7,561 (40.10%) | |||

| Restrictive | 8,338 (43.18%) | 204 (44.93%) | 8,134 (43.14%) | |||

| Vascular | 621 (3.22%) | 14 (3.08%) | 607 (3.22%) | |||

| Functional status at time of transplant | 821 (4.25%) | 39 (8.59%) | 782 (4.15%) | |||

| Performs activities of daily living with no assistance | 2,683 (13.90%) | 82 (18.06%) | 2,601 (13.79%) | |||

| Performs activities of daily living with some assistance | 10,872 (56.31%) | 228 (50.22%) | 10,644 (56.45%) | |||

| Performs activities of daily living with total assistance | 4,933 (25.55%) | 105 (23.13%) | 4,828 (25.61%) | |||

| Serum albumin before transplant | 4(3.6, 4.3) | 3,745 (19.40%) | 4(3.6, 4.2) | 109 (24.01%) | 4 (3.6, 4.3) | 3,636 (19.28%) |

| History of prior malignancy | 1,236 (6.40%) | 218 (1.13%) | 24 (5.29%) | 13 (2.86%) | 1,212 (6.43%) | 205 (1.09%) |

| PRA%—Class 1 > 0 | 2,964 (l5.35%) | 5,785 (29.96%) | 51 (11.23%) | 184 (40.53%) | 2,913 (15.45%) | 5,601 (29.71%) |

| PRA%—Class 2 > 0 | 2,036 (10.54%) | 6,885 (35.66%) | 30 (6.61%) | 211 (46.48%) | 2,006 (10.64%) | 6,674 (35.40%) |

| Recipient EBV-positive | 14,750 (76.39%) | 2,392 (12.39%) | 242 (53.30%) | 66 (14.54%) | 14,508 (76.95%) | 2,326 (12.34%) |

| Donor EBV-positive | 11,499 (59.55%) | 6,775 (35.09%) | 223 (49.12%) | 202 (44.49%) | 11,276 (59.80%) | 6,573 (34.86%) |

| Donor/recipient EBV match | 3,234 (16.75%) | 122 (26.87%) | 3,112 (16.50%) | |||

| Donor positive/recipient negative | 1,220 (6.32%) | 82 (18.06%) | 1,138 (6.04%) | |||

| Donor negative/recipient negative | 105 (0.54%) | 8 (1.76%) | 97 (0.51%) | |||

| Recipient positive | 14,750 (76.39%) | 242 (53.30%) | 14,508 (76.95%) | |||

| Recipient CMV-positive | 10,189 (52.77%) | 1,861 (9.64%) | 202 (44.49%) | 51 (11.23%) | 9,987 (52.97%) | 1,810 (9.60%) |

| Donor CMV-positive | 11,697 (60.58%) | 142 (0.74%) | 247 (54.41%) | 10 (2.20%) | 11,450 (60.73%) | 132 (0.70%) |

| Donor/recipient CMV match | 1,895 (9.81%) | 51 (11.23%) | 1,844 (9.78%) | |||

| Donor positive/recipient negative | 4,289 (22.21%) | 113 (24.89%) | 4,176 (22.15%) | |||

| Donor negative/recipient negative | 2,936 (15.21%) | 88 (19.38%) | 2,848 (15.10%) | |||

| Recipient positive | 10,189 (52.77%) | 202 (44.49%) | 9,987 (52.97%) | |||

| Recipient HBV-positive | 1,002 (5.19%) | 1,160 (6.01%) | 18 (3.96%) | 46 (10.13%) | 984 (5.22%) | 1,114 (5.91%) |

| Donor HBV-positive | 477 (2.47%) | 80 (0.41%) | 10 (2.20%) | 10 (2.20%) | 467 (2.48%) | 70 (0.37%) |

| Recipient HCV-positive | 317 (1.64%) | 1,812 (9.38%) | 7 (1.54%) | 54 (11.89%) | 310 (1.64%) | 1,758 (9.32%) |

| Donor HCV-positive | 14 (0.07%) | 121 (0.63%) | 0 (0.00%) | 18 (3.96%) | 14 (0.07%) | 103 (0.55%) |

| Donor history of high risk behaviors | 1,526 (7.90%) | 3,887 (20.13%) | 37 (8.15%) | 142 (31.28%) | 1,489 (7.90%) | 3,745 (19.86%) |

| Donor age, years | 32 (21, 46) | 1 (0.01%) | 29 (21, 44) | 0 (0.00%) | 32 (21, 46) | 1 (0.01%) |

| Donor history of cancer | 354 (1.83%) | 263 (1.36%) | 3 (0.66%) | 12 (2.64%) | 351 (1.86%) | 251 (1.33%) |

| Donor steroids | 14,406 (74.61%) | 900 (4.66%) | 339 (74.67%) | 33 (7.27%) | 14,067 (74.61%) | 867 (4.60%) |

Abbreviations: CMV, cytomegalovirus; EBV, Epstein–Barr virus; HBV, hepatitis B virus; HCV, hepatitis C virus; PRA, panel reactive antibody; PTLD, post-transplant lymphoproliferative disorder.

Continuous variables are summarized by median (25th percentile, 75th percentile); categorical variables are summarized by count (percentage).

Data collected in the ISHLT Registry are derived from real-world practice patterns reported into smaller registries. Missing data fields were expected based on specific registry collection instruments and varying completeness of collection. Covariates with high levels of missingness (>25%) were not considered in the inferential analysis.

Statistical analysis

To describe the timing and distribution of PTLD events after lung transplantation, the Kaplan–Meier method was used to obtain cumulative incidence estimates. Univariable and multivariable Cox proportional hazards regression models were used to examine the association between time to development of PTLD and recipient and donor characteristics. Associations were considered statistically significant if p < 0.05. To assess the proportional hazards assumption, the interaction between log time-to-event and each covariable was tested. If log-time–covariable interaction was statistically significant, the relationship between the covariable and PTLD was characterized by the interaction p-value and by reporting a set of hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% CIs over the follow-up period (1 year, 5 years, and 10 years); otherwise, a single HR, CI, and p-value were reported for the entire follow-up period.

For continuous covariables, linearity assumption was assessed by performing a lack-of-fit test comparing a linear fit with a non-linear fit based on a restricted cubic spline with 3 knots. If non-linearity was statistically significant, a piecewise linear spline was used to account for the non-linear relationship in the association model, and the relationship between covariable and PTLD was characterized by a global p-value and by reporting a set of HRs and 95% CIs, one for each component of the piecewise linear spline.

Multiple imputation was used to impute missing values for covariables with at most 25% missingness. Specifically, missing data were filled in 10 times using the Full Condition Specification method to generate 10 complete data sets, the 10 complete data sets were analyzed using standard statistical analyses, and results from 10 complete data sets are combined using Rubin’s Rule to produce the final association results. Multiple imputation was performed assuming that data are missing at random.17 Continuous, binary, and discrete variables were imputed using linear regression, logistic regression, and discriminant function, respectively, using observed ranges as bounds on the imputed values.

For both age and EBV match, the HR was allowed to vary continuously with event time (linearly on the log-hazard scale). This was achieved by creating an interaction term between each of the covariates and event time. As such, association results for age and EBV match are listed under the time-dependent covariables section of Table 3. Additionally, association between age and time to PTLD was found to be non-linear. To account for this non-linearity, a linear spline with 2 knots at baseline ages of 45 and 62 years was used. This approximation models the relationship between age and the hazard of PTLD linearly, but it allows the slope of the linear relationship to vary over 3 ranges created by the knots. Thus, HRs for age <45 years, between 45 and 62 years, and >62 years are reported. Each HR describes multiplicative change in the hazard of PTLD for a 5-year change in recipient age. This approximation of the non-linear relationship and the knots were chosen based on the restricted cubic spline fit, which allows more complex non-linear relationships.

Table 3.

Association between Pre- and Peri-Transplant Characteristics and Time to PTLD Development

| Covariates | Univariable modelsa |

Multivariable model |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) | p-value | HR (95% CI) | p-value | |

| Time dependent covariates | ||||

| Age (per 5 years) | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | ||

| At Year 1 | — | — | — | — |

| Age less than 45 years | 0.69 (0.63–0.77) | — | 0.79 (0.70–0.89) | — |

| Age between 45 and 62 years | 1.39 (1.23–1.58) | — | 1.42 (1.25–1.62) | — |

| Age greater than 62 years | 0.73 (0.56–0.96) | — | 0.70 (0.54–0.93) | — |

| At Year 5 | — | — | — | — |

| Age less than 45 years | 0.80 (0.71–0.91) | — | 0.89 (0.78–1.02) | — |

| Age between 45 and 62 years | 1.31 (1.15–1.49) | — | 1.34 (1.18–1.54) | — |

| Age greater than 62 years | 0.81 (0.51–1.29) | — | 0.77 (0.48–1.23) | — |

| At Year 10 | — | — | — | — |

| Age less than 45 years | 0.96 (0.75–1.24) | — | 1.03 (0.80–1.34) | — |

| Age between 45 and 62 years | 1.21 (0.93–1.57) | — | 1.25 (0.97–1.63) | — |

| Age greater than 62 years | 0.92 (0.33–2.58) | — | 0.85 (0.30–2.41) | — |

| EBV match | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | ||

| Donor negative/recipient negative | — | — | — | — |

| At Year 1 | 4.93 (2.47–9.82) | — | 4.65 (2.34–9.23) | — |

| At Year 5 | 3.04 (1.20–7.69) | — | 3.00 (1.22–7.38) | — |

| At Year 10 | 1.66 (0.26–10.8) | — | 1.74 (0.28–10.7) | — |

| Donor positive/recipient negative | — | — | — | — |

| At Year 1 | 5.15 (3.96–6.69) | — | 5.00 (3.81–6.56) | — |

| At Year 5 | 2.55 (1.64–3.97) | — | 2.60 (1.69–4.00) | — |

| At Year 10 | 1.06 (0.38–2.99) | — | 1.15 (0.42–3.16) | — |

| Recipient positive | — | — | — | — |

| Time independent covariates | ||||

| Native lung disease | 0.0056 | 0.0014 | ||

| Vascular | 1.19 (0.69–2.06) | — | 1.37 (0.78–2.43) | — |

| Cystic fibrosis | 1.81 (1.39–2.35) | — | 1.47 (0.95–2.26) | — |

| Restrictive | 1.47 (1.19–1.83) | — | 1.57 (1.25–1.96) | — |

| Obstructive | — | — | — | — |

| Bilateral transplant type | 1.09 (0.90–1.33) | 0.3657 | 1.09 (0.86–1.38) | 0.4803 |

| Male | 1.30 (1.08–1.58) | 0.0059 | 1.17 (0.96–1.43) | 0.1212 |

| Ischemia time | 1.03 (0.97–1.09) | 0.3270 | 1.03 (0.97–1.10) | 0.3605 |

| Type of induction at time of transplantb | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | ||

| Any cytolytic | 1.38 (1.09–1.76) | — | 1.47 (1.14–1.89) | — |

| Non-cytolytic | 0.77 (0.62–0.96) | — | 0.80 (0.64–1.00) | — |

| No induction | — | — | — | — |

| ABO exact match | 1.10 (0.77–1.57) | 0.6126 | 1.11 (0.77–1.59) | 0.5783 |

| Functional status at time of transplant | 0.1434 | 0.2641 | ||

| Performs activities of daily living with total assistance | 0.94 (0.70–1.28) | — | 0.91 (0.67–1.24) | — |

| Performs activities of daily living with some assistance | 0.80 (0.62–1.03) | — | 0.81 (0.63–1.05) | — |

| Performs activities of daily living with no assistance | — | — | — | — |

| Serum albumin before transplant | 0.88 (0.73–1.06) | 0.1701 | 1.02 (0.83–1.26) | 0.8219 |

| History of prior malignancy | 0.91 (0.60–1.37) | 0.6516 | 0.96 (0.63–1.46) | 0.8496 |

| PRA% class I > 0 | 0.85 (0.64–1.14) | 0.2685 | 0.91 (0.67–1.24) | 0.5404 |

| PRA% class II > 0 | 0.80 (0.56–1.13) | 0.1949 | 0.87 (0.60–1.26) | 0.4613 |

| Donor/recipient CMV match | 0.0045 | 0.2133 | ||

| Donor negative/recipient negative | 1.41 (1.10–1.81) | — | 1.21 (0.93–1.56) | — |

| Donor positive/recipient negative | 1.36 (1.08–1.71) | — | 1.19 (0.94–1.51) | — |

| Recipient positive | — | — | — | — |

| Recipient HCV-positive | 1.01 (0.48–2.12) | 0.9759 | 1.10 (0.52–2.30) | 0.8075 |

| Donor history of high risk behaviors | 1.42 (1.01–2.01) | 0.0459 | 1.42 (1.01–2.01) | 0.0489 |

| Donor age (per 5 years) | 0.97 (0.94–1.00) | 0.0917 | 0.98 (0.95–1.02) | 0.3760 |

| Donor history of cancer | 0.53 (0.10–2.77) | 0.4355 | 0.59 (0.11–3.14) | 0.5209 |

| Donor steroids | 1.09 (0.85–1.39) | 0.4888 | 1.10 (0.86–1.40) | 0.4616 |

Abbreviations: CMV, cytomegalovirus; EBV, Epstein–Barr virus; HCV, hepatitis C virus; HR, hazard ratio; PRA, panel reactive antibody; PTLD, post-transplant lymphoproliferative disorder.

Univariable model includes only one covariate; multivariable model includes all covariates listed.

Recipients receiving both cytolytic and non-cytolytic induction are grouped with cytolytic alone.

Before the analysis, due to small size the LTRs who received both cytolytic and non-cytolytic agents (n = 91) at induction were combined with LTRs who received cytolytic agents (n = 2893), into one group called any cytolytic (Table 3).

Results

Patient characteristics

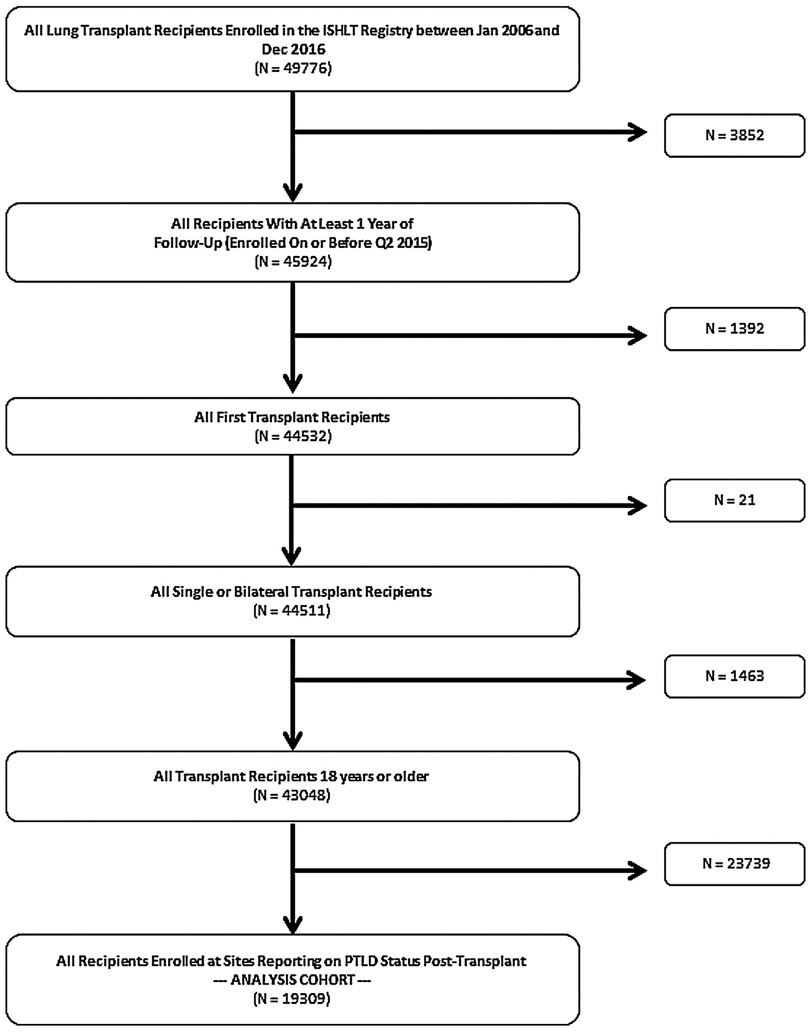

ISHLT Registry data for 49,776 lung transplants performed between January 2006 and December 2016 were included. We excluded from analysis 3,852 LTRs with <1 year of follow-up, 1,392 LTRs receiving retransplantation, 21 LTRs receiving lobar lung transplant, 1,463 patients younger than 18 years of age, and 23,739 LTRs from centers not reporting PTLD during follow-up (Figure 1). Thus, the analysis cohort included 19,309 adult first LTRs.

Figure 1. Flowchart showing selection of the final study population.

ISHLT, International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation; LTR, lung transport recipient; PTLD, post-transplant lymphoproliferative disorder.

Clinical characteristics of the study cohort are described in Table 1. PTLD occurred in 454 (2.35%) LTRs. Median age at transplantation was 57 years, and 43.1% were women. Most LTRs (98.8%) reported to the ISHLT Registry were from the North America region. The most common indications for transplantation were restrictive disease (43.2%), obstructive disease (39.9%), and cystic fibrosis (13.6%). At time of transplant, 43.8% of LTRs received no induction, 39.6% received non-cytolytic agents (basiliximab and daclizumab), and 14.9% of LTRs received cytolytic agents (Okt-3, polyclonal anti-thymocyte globulin, and alemtuzumab). In 91 LTRs (0.47%), both cytolytic and non-cytolytic agents were used. Distribution of these covariates were similar between patients with and patients without PTLD. However, we observed some notable differences. In the PTLD group, 53.3% of LTRs were EBV seropositive and EBV mismatch (donor + and recipient −) was reported in 18.16% compared with 77% EBV+ and 6% of mismatch in the rest of LTRs. Characteristics among LTRs included and excluded from the analysis are described in Supplementary Table S1, available online at www.jhltonline.org.

Incidence of PTLD

The cumulative incidence of PTLD was 1.14% (95% CI, 0.99%–1.29%) during the first year, 2.47%% (95% CI, 2.21%–2.73%) at 5 years, and 4.12% (95% CI, 3.6%–4.63%) at 10 years after transplantation (Figure 2 and Table 2). Of those who developed PTLD, 47.4% (215 out of 454) of cases occurred within 1 year after lung transplantation.

Figure 2. Cumulative incidence of PTLD after lung transplant in a cohort of 19,309 LTRs.

The numbers below the curve are numbers of patients being followed up at yearly intervals post–lung transplant and at risk of developing PTLD. PTLD, post-transplant lymphoproliferative disorder.

Table 2.

Cumulative Event Counts and KM Rates for PTLD

| Cumulativeevent counta | Number of patients at risk |

KM eventprobability (95% CI)b | |

|---|---|---|---|

| At 1 year | 215 | 17,328 | 1.14% (0.99%–1.29%) |

| At 3 years | 319 | 11,150 | 1.85% (1.65%–2.05%) |

| At 5 years | 376 | 6,740 | 2.47% (2.21%–2.73%) |

| At 10 years | 436 | 1,588 | 4.12% (3.60%–4.63%) |

| At 15 years | 453 | 143 | 6.54% (5.12%–7.96%) |

Abbreviations: KM, Kaplan–Meier; PTLD, post-transplant lymphoproliferative disorder.

A total of 454 PTLD events were observed in the analysis cohort with a maximum follow-up time of 17 years.

The Kaplan–Meier method estimates the probability an event occurs on or before a given time point.

Risk factors for PTLD

Results of univariable and multivariable Cox regression modeling for time to PTLD are presented in Table 3. When exploring the association between pre- and peri-transplant characteristics and time to PTLD, the proportional hazards assumption was found to be violated for recipient age and EBV matching, suggesting an association between each of these characteristics and the hazard of developing PTLD changes during the follow-up period. To account for this non-proportionality, time-dependent covariates were created for these characteristics.

Both unadjusted and adjusted associations between age and development of PTLD were statistically significant (p < 0.0001 for both models). Using the multivariable model, we found that at 1 year post-transplantation, the risk of PTLD decreased with increasing age for subjects younger than 45 years at time of transplant (HR, 0.79 per 5-year increase; 95% CI, 0.7–0.89); the risk of PTLD increased with increasing age for subjects between 45 and 62 years at time of transplant (HR, 1.42 per 5-year increase; 95% CI, 1.25–1.62), and finally, the risk of PTLD decreased with increasing age for subjects older than 62 years at time of transplant (HR, 0.7 per 5-year increase; 95% CI, 0.54–0.93). A similar pattern was observed at 5 and 10 years post-transplantation. However, the strength of the association diminished over time, remaining statistically significant only at 5 years post-transplantation (Figure 3, Table 3).

Figure 3. Adjusted log-hazard of PTLD as a function of age at transplant.

A linear spline with 2 knots at baseline ages of 45 and 62 years was used to account for the non-linear association between age at transplant and time to development of PTLD. HRs for 3 age groups, <45 years old, between 45 and 62 years, and >62 years old, are reported. HR, hazard ratio; PTLD, post-transplant lymphoproliferative disorder.

Similarly, in both association models, EBV serostatus match was found to be significantly associated with PTLD (p < 0.0001 for both models). Using the multivariable model, we found that at 1 year post-transplantation, relative to EBV seropositive LTRs (regardless of donor status), transplants in which donor and recipient were EBV-negative (HR, 4.65; 95% CI, 2.34–9.23) and mismatched transplants (donor +/recipient −) (HR, 5; 95% CI, 3.81–6.56) were associated with an increased risk of PTLD. The strength of both of these associations attenuated over time, remaining statistically significant only at 5 years post-transplantation.

We then analyzed the association between time-independent covariables and PTLD after lung transplantation. We observed that native lung disease (p = 0.0014), induction (p < 0.0001), and donor’s history of increased risk behaviors, defined as donor characteristics that could potentially increase the risk of disease transmission to recipients as defined by local organ allocation guidelines and reported to the Registry,18 (p = 0.0489) were found to be independently associated with PTLD in the multivariable model. Recipients with cystic fibrosis had a statistically significant increased risk of PTLD only in the univariable model (HR, 1.81; 95% CI, 1.39–2.35), whereas recipients with restrictive disease had a statistically significant increased risk of PTLD compared with those with obstructive disease in both models (univariable HR, 1.47; 95% CI, 1.19–1.83 and multivariable HR, 1.57; 95% CI, 1.25–1.96).

Induction immunosuppression was associated with PTLD in both the univariable and multivariable models (p < 0.0001 for both models). The association was driven by recipients receiving any cytolytic induction at time of transplant compared with LTRs receiving no induction (univariable HR, 1.38; 95% CI, 1.09–1.76 and multivariable HR, 1.47; 95% CI, 1.14–1.89).

LTRs whose donors had a history of increased risk behaviors had a statistically significant increased risk of PTLD (HR, 1.42; 95% CI, 1.01–2.01).

In the unadjusted model, males had a higher risk of PTLD than females (HR, 1.30; 95% CI, 1.08–1.58, p = 0.006). However, after adjusting for other characteristics, this association was not statistically significant (p = 0.10). Finally, in the unadjusted model, relative to CMV-seropositive recipients (regardless of donor status), transplants in which donor and recipient were CMV-negative (HR, 1.41; 95% CI, 1.10–1.81) and mismatched transplants (donor +/recipient −) (HR, 1.36; 95% CI, 1.08 −1.71, p = 0.0045) were associated with an increased risk of PTLD. The adjusted association was not found to be statistically significant.

HLA and risk of PTLD

We analyzed the unadjusted and adjusted association between donor and recipient HLAs and risk of PTLD. Only serological HLA typing was reported to the ISHLT Registry. In both models, transplants involving donors with HLA-A1, when compared with donors without HLA-A1 (multivariable HR, 1.27; 95% CI, 1.03–1.56, p = 0.02 6), and HLA-A24, when compared with donors without HLA-A24 (multivariable HR, 1.30; 95% CI, 1.03–1.63, p = 0.0272), were associated with an increased risk of PTLD. Similarly, transplants involving recipients with HLA-DR11 were associated with a decreased risk of PTLD compared with donors without HLA-DR11 (multivariable HR, 0.74; 95% CI, 0.55–1, p = 0.045). (Supplementary Table S2 online and Figure 4).

Figure 4. Hazard ratio for PTLD by HLA type.

Donors (top), Recipients (bottom). HLA, human leukocyte antigen; PTLD, post-transplant lymphoproliferative disorder.

Discussion

PTLD is a rare but life-threatening complication following transplantation. Several single-center analyses have identified numerous risk factors associated with PTLD such as primary EBV infection, organ transplanted, age, Caucasian race, and CMV mismatch.9,19-21 However, these analyses are often limited by their small size. To our knowledge, for the first time with this study, we evaluated the incidence and identified pre- and peri-transplant clinical characteristics associated with PTLD in a large, international multicenter adult LTR population using the ISHLT Registry. The most important finding of this study is that, despite low overall incidence, the cumulative incidence reaches 4.4% at 10 years post-transplantation. We observed a non-linear association between age and risk of PTLD, with increasing risk in LTRs between 45 and 62 years old at transplant but decreasing risk with age below and above this age range. Other risk factors were a recipient negative EBV serostatus, restrictive lung disease, and induction. Finally, we observed an increased risk of PTLD from donor organs with HLA-types A1 and A24 and decreased risk in recipients with HLA-DR11.

In this study of the ISHLT Registry database, we found that there is a sustained increase in the cumulative risk of developing PTLD following lung transplant. The overall incidence of PTLD is small, lower than reported in prior studies in lung transplantation.10,11,21-23However, several centers participating in the ISHLT Registry have not reported PTLD consistently over time, and this might explain lower than expected incidence. Similarly to previous studies,2,6,9 we noted that approximately 50% of PTLD cases occurred during the first year after lung transplant. This heightened risk could be partially explained by the intensity of immunosuppression. Particularly, during the first year after transplantation, stronger immunosuppression and less efficient host immune response against EBV might predispose to malignant transformation of EBV-infected cells.

Age is an important risk factor for PTLD at different times after transplantation. Younger individuals have a high risk of PTLD during the first year, whereas older recipient age has emerged as a risk factor for late cases of PTLD.19 Retrospective analyses of SOT recipients reported an increased risk of PTLD in patients older than 50 years.24,25 We observed a similar risk in LTRs. In our detailed analysis around recipient age, we noted a non-linear association between age and risk of PTLD in adult LTRs. Risk of PTLD declined with increasing age for recipients younger than 45 years, whereas risk of PTLD increased for recipients between 45 and 62 years at time of transplant.

Our study confirms that LTRs with negative EBV serostatus have an increased risk of PTLD. Both EBV mismatch and EBV donor and recipient negative LTRs showed an increased risk of PTLD. Similar findings were described in pediatric kidney transplant recipients but also in adult recipients when using an EBV– living donor.26 Unfortunately, EBV seroconversion and EBV viral load after lung transplant were not reported to the Registry. In our opinion, primary EBV infection either from the community or the donor plays a key role in the development of PTLD. Therefore, LTRs with negative EBV serostatus require more attentive monitoring following transplantation.

LTRs with restrictive disease were demonstrated to have an increased risk of PTLD in our analysis. Although several possible explanations for this finding could be considered, EBV infection has been implicated in the pathogenesis of restrictive lung disease, implying loss of immune surveillance in this patient group.27

Previous analyses on the risk of PTLD with induction immunosuppression have inconsistent results.19,20,28 We demonstrated that the use of induction is associated with increased risk of PTLD in LTRs. In our analysis, use of any cytolytic agent is associated with significant risk of PTLD, whereas non-cytolytic agents appear to be protective. This finding suggests that depletion of T cells, likely including EBV-specific T cells, could increase the risk of PTLD.

The association between donor’s increased risk behaviors and PTLD is surprising. It possible that coinfection with other pathogens, such as human herpesviruses 6 or 8, could increase the risk of PTLD. Unfortunately, no data regarding the incidence of less common viral infections are available in the ISHLT Registry. The role of CMV in development of PTLD in thoracic transplant recipients remains contradictory.9,10,29 In our analysis, CMV-negative recipient status was only associated with PTLD in the unadjusted model, confirming that CMV mismatch should not be considered a major risk factor in LTRs. A recent systematic review demonstrated no significant difference in the rate of EBV-related PTLD in SOT recipients with or without antiviral prophylaxis.30 Of note, valganciclovir was available for LTRs during our study period.

Previous observational reports demonstrated an increased risk of PTLD with different HLA alleles. Two single-center analyses from U.S. centers described an increased risk of PTLD with HLA A-26, B8, and B40 groups and risk reduction associated with donor HLA- A1, B8, and DR3.13,15 These associations are different from those found in our international Registry analysis. Our conclusions should be considered in light of several limitations. Only serological HLA typing was reported, rather than molecular typing, which could provide a more detailed assessment of any association. Our HLA analysis may be subject to Type I error given high numbers of loci analyzed for a relatively small numbers of outcomes. We could not analyze the impact of donor/recipient HLA mismatching. However, our analysis included a larger cohort compared with previous analyses and serological typing was also used in the majority of those studies.

This study presents several further limitations. This was a retrospective analysis that linked pre- and peri-transplant clinical characteristics with subsequent PTLD reporting. Thus, we cannot draw any conclusions regarding causation. Of note, the ISHLT Registry was not specifically developed to look at PTLD and therefore this study is limited to the data captured by the Registry. Some variables had a large percentage of missing data or were not captured in the Registry and therefore could not be included in the analysis. Moreover, the vast majority of the reporting centers were from the North America region. This potentially limits both generalizability of the study’s results and broader evaluation of incidence and risk factors.

In conclusion, this analysis describes a large cohort of adult LTRs with PTLD, allowing meaningful assessment of incidence and risk factors. We noted an increasing cumulative incidence of PTLD following lung transplantation, with the highest risk during the first year. EBV-sero-negative recipients were at highest risk of PTLD, regardless of donor serostatus and independent of other factors. We noted a complex relationship between age at transplant and PTLD risk and an increased risk, independent of other factors, in recipients with restrictive lung disease and with the use of any cytolytic agents as induction. Our findings will assist clinicians caring for patients after lung transplantation to target PTLD surveillance to the populations at highest risk.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the ISHLT Transplant Registry Early Career Award.

Footnotes

Disclosure statement

The authors have no conflict of interest to disclose.

Supplementary materials

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found in the online version at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healun.2020.06.010.

References

- 1.Al-Mansour Z, Nelson BP, Evens AM. Post-transplant lymphoproliferative disease (PTLD): risk factors, diagnosis, and current treatment strategies. Curr Hematol Malig Rep 2013;8:173–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sampaio MS, Cho YW, Qazi Y, Bunnapradist S, Hutchinson IV, Shah T. Posttransplant malignancies in solid organ adult recipients: an analysis of the U.S. National Transplant Database. Transplantation 2012;94:990–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chambers DC, Cherikh WS, Goldfarb SB, et al. The International Thoracic Organ Transplant Registry of the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation: thirty-fifth adult lung and heart-lung transplant report-2018; focus theme: multiorgan transplantation. J Heart Lung Transplant 2018;37:1169–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Peters AC, Akinwumi MS, Cervera C, et al. The changing epidemiology of posttransplant lymphoproliferative disorder in adult solid organ transplant recipients over 30 years: a single-center experience. Transplantation 2018;102:1553–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dharnidharka VR, Webster AC, Martinez OM, Preiksaitis JK, Leblond V, Choquet S. Post-transplant lymphoproliferative disorders. Nat Rev Dis Primers 2016;2:15088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dharnidharka VR, Lamb KE, Gregg JA, Meier-Kriesche HU. Associations between EBV serostatus and organ transplant type in PTLD risk: an analysis of the SRTR National Registry Data in the United States. Am J Transplant 2012;12:976–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Saueressig MG, Boussaud V, Amrein C, Guillemain R, Souilamas J, Souilamas R. Risk factors for post-transplant lymphoproliferative disease in patients with cystic fibrosis. Clin Transplant 2011;25:E430–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lowery EM, Adams W, Grim SA, Clark NM, Edwards L, Layden JE. Increased risk of PTLD in lung transplant recipients with cystic fibrosis. J Cyst Fibros 2017;16:727–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Allen U, Preiksaitis J, AST Infectious Diseases Community of Practice. Epstein-Barr virus and posttransplant lymphoproliferative disorder in solid organ transplant recipients. Am J Transplant 2009;9(Suppl 4):S87–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gao SZ, Chaparro SV, Perlroth M, et al. Post-transplantation lymphoproliferative disease in heart and heart-lung transplant recipients: 30-year experience at Stanford University. J Heart Lung Transplant 2003;22:505–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Leyssens A, Dierickx D, Verbeken EK, et al. Post-transplant lymphoproliferative disease in lung transplantation: a nested case-control study. Clin Transplant 2017;31:e12983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vase MØ, Maksten EF, Strandhave C, et al. HLA associations and risk of posttransplant lymphoproliferative disorder in a Danish population-based cohort. Transplant Direct 2015;1:e25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lustberg ME, Pelletier RP, Porcu P, et al. Human leukocyte antigen type and posttransplant lymphoproliferative disorder. Transplantation 2015;99:1220–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Subklewe M, Marquis R, Choquet S, et al. Association of human leukocyte antigen haplotypes with posttransplant lymphoproliferative disease after solid organ transplantation. Transplantation 2006;82:1093–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Reshef R, Luskin MR, Kamoun M, et al. Association of HLA polymorphisms with post-transplant lymphoproliferative disorder in solid-organ transplant recipients. Am J Transplant 2011;11:817–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kinch A, Sundström C, Tufveson G, Glimelius I. Association between HLA-A1 and -A2 types and Epstein-Barr virus status of post-transplant lymphoproliferative disorder. Leuk Lymphoma 2016;57:2351–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Little RJA, Rubin DB. Statistical analysis with missing data. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lehr CJ, Lopez R, Arrigain S, Schold J, Koval C, Valapour M. The impact of change in definition of increased-risk donors on survival after lung transplant [e-pub ahead of print]. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2019.10.154, accessed May 15, 2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Opelz G, Döhler B. Lymphomas after solid organ transplantation: a collaborative transplant study report. Am J Transplant 2004;4:222–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dharnidharka VR, Tejani AH, Ho PL, Harmon WE. Post-transplant lymphoproliferative disorder in the United States: young Caucasian males are at highest risk. Am J Transplant 2002;2:993–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Aris RM, Maia DM, Neuringer IP, et al. Post-transplantation lymphoproliferative disorder in the Epstein-Barr virus-naive lung transplant recipient. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1996;154:1712–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Paranjothi S, Yusen RD, Kraus MD, Lynch JP, Patterson GA, Trulock EP. Lymphoproliferative disease after lung transplantation: comparison of presentation and outcome of early and late cases. J Heart Lung Transplant 2001;20:1054–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zimmermann H, Choquet S, Dierickx D, et al. Early and late posttransplant lymphoproliferative disorder after lung transplantation—34 cases from the European PTLD Network. Transplantation 2013;96:e18–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Quinlan SC, Pfeiffer RM, Morton LM, Engels EA. Risk factors for early-onset and late-onset post-transplant lymphoproliferative disorder in kidney recipients in the United States. Am J Hematol 2011;86:206–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Opelz G, Henderson R. Incidence of non-Hodgkin lymphoma in kidney and heart transplant recipients. Lancet 1993;342:1514–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sampaio MS, Cho YW, Shah T, Bunnapradist S, Hutchinson IV. Impact of Epstein-Barr virus donor and recipient serostatus on the incidence of post-transplant lymphoproliferative disorder in kidney transplant recipients. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2012;27:2971–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sheng G, Chen P, Wei Y, et al. Viral infection increases the risk of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: a meta-analysis. Chest 2020;157:1175–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Caillard S, Lamy FX, Quelen C, et al. Epidemiology of posttransplant lymphoproliferative disorders in adult kidney and kidney pancreas recipients: report of the French registry and analysis of subgroups of lymphomas. Am J Transplant 2012;12:682–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Walker RC, Marshall WF, Strickler JG, et al. Pretransplantation assessment of the risk of lymphoproliferative disorder. Clin Infect Dis 1995;20:1346–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.AlDabbagh MA, Gitman MR, Kumar D, Humar A, Rotstein C, Husain S. The role of antiviral prophylaxis for the prevention of Epstein-Barr virus-associated posttransplant lymphoproliferative disease in solid organ transplant recipients: a systematic review. Am J Transplant 2017;17:770–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.