Abstract

The impurity of salicylic acid (SA) in aspirin is a required inspection item for drug quality control. Since free SA is significantly toxic for humans, the content determination of free SA is absolutely necessary to ensure people's health. In this work, a facile colorimetric method was developed for the detection of SA in aspirin by utilizing the MIL-53(Fe) nanozyme. As MIL-53(Fe) possesses enzyme mimicking catalytic activity, 3,3,5,5-tetramethylbenzidine (TMB) can be easily oxidized to blue-oxidized TMB (oxTMB) with the existence of H2O2. Moreover, an inhibition effect on the catalytic activity of the MIL-53(Fe) nanozyme is induced due to the specific complexation between SA and Fe3+ in the center of MIL-53(Fe), which results in a lighter color in the oxTMB. The color change of oxTMB can be seen easily by the naked eye with the addition of different concentrations of SA. Thus, a simple colorimetric platform was established for effectively monitoring SA. A good linear relationship (R2 = 0.9990) was obtained in the concentration range of 0.4–28 μmol L−1, and the detection limit was 0.26 μmol L−1. In particular, the rationally designed system has been well-applied to the detection of SA impurity in aspirin. Satisfyingly, the detection results are highly in accord with those of HPLC. This novel colorimetric platform broadens the application prospects of nanozymes in the field of pharmaceutical analysis.

Keywords: aspirin, complexation, colorimetric detection, MIL-53(Fe), nanozyme, salicylic acid

Introduction

Salicylic acid (SA), as a major phytohormone, generally plays an important role in regulating diverse physiological processes such as defense responses, thermogenesis, and germination (Wang et al., 2010; Marques et al., 2020). SA is a promising material and it is commonly exploited in the manufacture of pharmaceutical products (Kopp and Ghosh, 1994). Additionally, SA is widely used in the cosmetics industry as an organic acid (Chanakul et al., 2016). Thus, SA has broadened application prospects in many fields. However, SA is one of the common pollutants in industrial wastewater (Collado et al., 2010). More importantly, SA may cause some toxic side effects on the human body. Because of its relatively strong acidity, SA can not only stimulate and damage the mouth, esophagus, and gastric membrane, but can also invoke adverse symptoms such as metabolic disorders, ototoxicity, fetal malformations, and central nervous system depression (Tian et al., 2009). Aspirin, as a widely used drug, has the effects of an antipyretic, analgesic and anti-inflammatory (Dahl and Kehlet, 1991; Parham and Rahbar, 2009). However, SA can be easily produced due to the incomplete acetylation in the production process of aspirin or hydrolysis during the refining process and storage. Besides, the phenolic hydroxyl group in the free SA is readily oxidized and consequently form a series of colored quinone compounds, leading to discoloration of aspirin. There have corresponding safety limits for free SA in aspirin in countries around the world. From the above consideration, the contents of SA need to be frequently determined to ensure people's health.

There have been many analytical strategies for the detection of SA so far. For instance, one common analysis method is the spectrophotometric Trinder test, which is based on the formation of a coordination complex between SA and Fe3+ (Shokrollahi et al., 2017). Beyond that, many chromatography-based methods like high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) (Aboul-Soud et al., 2004; Croubels et al., 2005), gas chromatography (GC) (Tanchev et al., 1980), HPLC-MS/MS (Uddin et al., 2014), GC-MS (Huang et al., 2015), and ultra-HPLC (UHPLC) coupled MS/MS spectrometry (Floková et al., 2014), have been previously reported for SA detection. Capillary electrophoresis (CE) is an alternative to HPLC-based methods by virtue of the high separation efficiency and low solvent consumption advantages. Lin's group designed an iron oxide-based solid phase extraction system coupled to CE-UV for analyzing SA (Chang et al., 2017). This method shows excellent sensitivity for SA detection. Furthermore, there was an electrochemical sensor developed for determination of SA recently, in order to improve the sensitivity and accuracy, the composite of multi-wall carbon nanotubes (MWNT) and carbon black (CB) was fabricated, and ferrocene (Fc) was exploited as the reference molecule to offer a built-in correction (Hu et al., 2020). In addition, a work from Wang and co-workers reported that a nanosensor had been prepared based on the structure-switching strategy, and the SA aptamer showed a good affinity to SA (Chen et al., 2019).

In comparison with other methods, the colorimetric method has garnered extensive attention due to its superior responsiveness, portability, and practicality with no need for expensive and cumbersome instruments (Yan et al., 2020). Additionally, the detection result is easy to read out with visual inspection (Hao et al., 2013; Fan et al., 2017). In some research, a colorimetric assay has been developed for the detection of SA using TiO2 NPs. This nanomaterial shows good selectivity for SA, however, the sensitivity of detection is limited (Tseng et al., 2014). In another report, Yang's group developed two rhodamine-based fluorescent probes that could realize bioimaging of SA (Wang et al., 2019a). This colorimetric sensor not only possesses good selectivity and sensitivity toward SA but detection is also observable with the naked-eye. At the same time, it has some shortcomings. The method is time-consuming, involves fussy operation steps, and it is difficult to fabricate probes using it. Previous studies have made it clear that nanozymes can be used in the field of colorimetric sensing owing to the advantages of simple preparation, low cost, and high catalytic activity. In particular, based on the improvement of enzyme catalytic activity, many studies have been carried out to achieve the purpose of colorimetric detection (Zhang et al., 2018; Li et al., 2019). Besides, most studies have focused on the design of nanozymes with different activities for colorimetric sensing of biothiols (Xiong et al., 2015; Song et al., 2020), dopamine (Wang et al., 2019b), glutathione reductase (Zhang et al., 2019), and acid phosphatase (Lin et al., 2020). These sensors generally achieve the goal of detection by using reduced substances to interfere with the oxidation of chromogenic substrates or to reduce oxTMB. However, these methods are usually affected by substances with strong reducibility, and thus the samples generally need to be pretreated. In contrast, few reports have been devoted to designing a scheme for specifically inhibiting the activity of nanozymes to ensure the selectivity of colorimetric sensing.

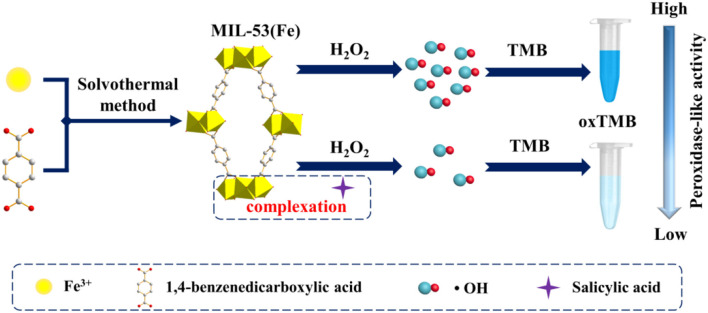

Thus, herein, inspired by the specific complexation reaction between SA and Fe3+, and considering that no efforts have been made toward colorimetric detection of SA in aspirin by utilizing a metal-organic framework (MOF) nanozyme. we select MIL-53(Fe) as the nanozyme serving to achieve colorimetric detection of SA (Figure 1). As a result, the as-prepared MIL-53(Fe) shows high peroxidase-like activity in catalyzing 3,3,5,5-tetramethylbenzidine (TMB) oxidation and thus makes it a blue color in the presence of H2O2. Interestingly, because of the complexation reaction of SA and Fe3+ in the center of MIL-53(Fe), the catalytic activity of MIL-53(Fe) is inhibited significantly with the addition of SA. Based on this, a simple colorimetric sensor was successfully developed to detect SA. The proposed system furnishes a cost-effective, highly selective, and sensitive strategy for the colorimetric detection of SA and broadens the application potential of MOF nanozymes in the field of pharmaceutical analysis.

Figure 1.

Schematic illustration of MIL-53(Fe) synthesis and colorimetric detection of SA based on the MIL-53(Fe) nanozyme.

Experimental

Materials

Acetic acid (HAc), H2O2 (30 wt%), N,N'-dimethylformamide (DMF), sodium acetate (NaAc), salicylic acid (SA), and 1,4-benzenedicarboxylic acid (H2BDC) were acquired from Beijing HWRK Chem Co., LTD. (China). Iron chloride hexahydrate (FeCl3·6H2O) and TMB were bought from Shanghai Macklin Biochemical Co., Ltd. (China). All the chemicals mentioned above were analytical grade and used as received. Aspirin was purchased from Shanghai Titan Scientific Co., Ltd. Ultra-pure water came from the Millipore purification system (18.2 MΩ).

Apparatus

The powder X-ray diffraction (XRD) pattern of MIL-53(Fe) was recorded with a D/max 2,550 VB/PC diffractometer (Rigaku, Japan) using Cu Kα radiation (λ = 0.15418 nm). Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and transmission electron microscopy (TEM) pictures were taken using Quanta 200 FEG (Netherlands) and Tecnai G2 20 (PE, USA), respectively. A Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectra was obtained from spectrum-2000 (USA). Thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) was carried out by the LABSYS evo TG-DSC/DTA instrument (Setaram Instrumentation, France). The UV-Vis absorption spectrum was recorded on the Cary 60 spectrophotometer (Agilent, USA). And HPLC was performed on the liquid chromatography instrument (Shimadzu, Japan) with the LC-20AT pump and the SPD-20A UV-vis detector.

Preparation of MIL-53(Fe)

MIL-53(Fe) was synthesized with a solvothermal method referring to the literature with a minor modification (Millange et al., 2010). Typically, 1.0812 g FeCl3·6H2O was dissolved in 20 mL of DMF solution before adding 0.6646 g of H2BDC. After 10 min of intense stirring, the solution was transferred to a 50 mL stainless-steel autoclave and then heated at 150°C for 48 h. After natural cooling, the yellow precipitate was collected by centrifugation and washed with distilled water and ethanol. Finally, the yellow precipitate was dried in vacuum at 60°C overnight.

Detection of SA

To obtain a standard curve, SA detection was conducted as follows: 70 μL 1 mg/mL MIL-53(Fe) and 25 μL aliquots of SA solution of different concentrations were added to 875 μL 0.1 M pH 3.5 acetate buffers. After incubating for 4 min, 30 μL 4 mM TMB and 25 μL 0.1 M H2O2 were added to the above solution, and the solution was shaken and incubated at 37°C for 8 min. Finally, a Cary 60 spectrophotometer was used for analyzing the mixed solution.

Analysis of SA in Aspirin Sample

A standard addition method was applied for the determination of SA in aspirin. The sample was prepared as follows: 100 mg of aspirin powder was dissolved in 1% glacial acetic acid methanol solution (100 mL) and then filtered through a 0.45 μm filter paper. Next, the filtrate (100 μL) was placed in 0.1 M pH 3.5 acetate buffers. Subsequently, 70 μL 1 mg/mL of MIL-53(Fe) and different concentrations of SA were added. After incubating for 4 min, 30 μL 4 mM TMB and 25 μL 0.1 M H2O2 were added. At last, the mixture was incubated at 37°C for 8 min, the resulting solution was analyzed by the proposed colorimetric method, and the corresponding recoveries were obtained.

Results and Discussion

Characterization of MIL-53(Fe)

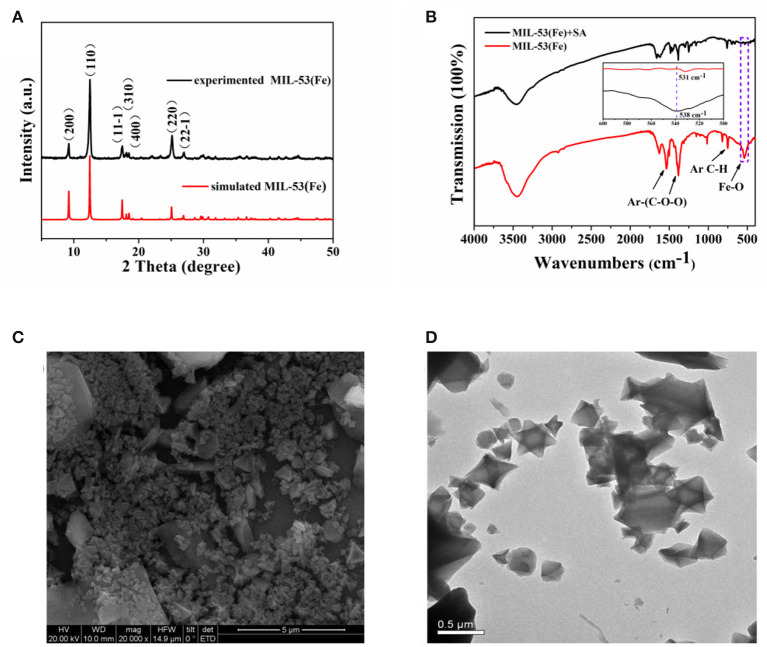

The structure of MIL-53(Fe) was characterized first by XRD. As Figure 2A shows, particles of MIL-53(Fe) are highly crystalline, and the obvious sharp diffraction peaks correspond to the previously reported results as well as the simulated results (Lin et al., 2018). In addition, FTIR spectra was utilized for identifying the characteristic functional groups. As can be seen from Figure 2B, the spectrum clearly exhibits the typical asymmetrical and symmetrical vibration bands of carboxyl groups on the ligand, which indicates the existence of a dicarboxylate linker in MIL-53(Fe). Meanwhile, the C-H bending vibration of the benzene ring is observed and the stretching vibration of the Fe-O bond well-explains the formation of the metal-oxo cluster between Fe(III) and the carboxylic group of the organic linker. However, in the presence of SA, the absorption peak of the Fe-O bond shifted from 538 to 531 cm−1, this result indicates that SA reacts with MIL-53(Fe) to form an iron salicylate complex. Furthermore, the morphology of MIL-53(Fe) was characterized by SEM and TEM. As shown by the images, the particles of MIL-53(Fe) have a very regular octahedron crystal structure (Figures 2C,D). Afterwards, the mass loss was explored via thermogravimetric analysis (TGA), it was ascertained that the first mass loss (~39.27%) was due to the dehydration of MIL-53(Fe), and the subsequent mass loss (~56.56%) corresponded to the collapse of MIL-53(Fe) into Fe2O3. The result from Figure S1 is well-within the expected range according to the previous report (Millange et al., 2010). It could be concluded that MIL-53(Fe) was synthesized successfully with overall consideration in the characterization results above.

Figure 2.

(A) PXRD patterns of the as-prepared MIL-53(Fe) (black curve) and the simulated MIL-53(Fe) (red curve), (B) FTIR spectra of MIL-53(Fe) and MIL-53(Fe)+SA, (C,D) depicting the SEM and TEM images of MIL-53(Fe), respectively.

Detection Principle

In recent years, MIL-53(Fe) has been demonstrated exhibiting intrinsic peroxidase-mimicking catalytic activity and has been used for the colorimetric detection of ascorbic acid (AA) (Ai et al., 2013). In the presence of H2O2, the chromogenic substrates are oxidized with the catalytic effect of the MIL-53(Fe) nanozyme. As a result, the color of the solution is changed. In this work, a lighter color of oxTMB is created due to the inhibitory effect of SA on MIL-53(Fe) activity. Aiming at this phenomenon, a facile colorimetric platform was established to monitor SA (Figure 1). During the experiment, MIL-53(Fe) and SA were incubated in an acetate buffer for 4 min, then TMB and H2O2 were added and the mixture was incubated at 37°C for 8 min. In the absence of SA, MIL-53(Fe) maintains its catalytic activity and a deep blue color for oxTMB emerges in the MIL-53(Fe)/TMB/H2O2 system. On the contrary, SA has strong complexation ability with Fe3+ in the center of MIL-53(Fe). After the addition of SA, the peroxidase-like activity of MIL-53(Fe) is significantly inhibited due to the reaction of SA and Fe3+ (Figure 1). Consequently, the catalytic oxidation of TMB begins to decelerate, enabling the blue color solution to lighten. The color change is easy to identify by the naked eye. The catalytic activity of MIL-53(Fe) and the absorption intensity of oxTMB at 652 nm are dependent on the SA concentration. Thus, the MIL-53(Fe)/TMB/H2O2 system is capable for the colorimetric detection of SA.

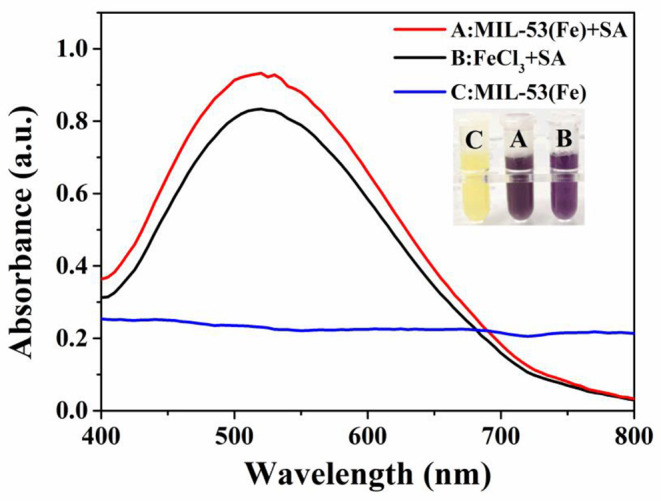

To illuminate the mechanism of inhibitory effects of SA on the MIL-53(Fe) activity, the purple complex of SA-Fe(III) was characterized by UV-Vis absorbance spectroscopy. As revealed by Figure 3, a conspicuous absorption peak at ~520 nm appears when FeCl3 is used as the standard sample to incubate with SA (Chang et al., 2017; Bodek et al., 2020), and the color of the solution changes to purple. Likewise, the same absorption peak at 520 nm occurs when MIL-53(Fe) and SA are incubated together. The solution of MIL-53(Fe) is yellow and has turned a dark purple color with the addition of SA. Obviously, no peak appears at 520 nm when there is only MIL-53(Fe) in the solution. What this suggests is that Fe(III) in the center of MIL-53(Fe) forms a purple complex with SA and results in the inhibited activity of MIL-53(Fe).

Figure 3.

The absorption peaks of SA-Fe(III) complex characterized by UV-Vis spectra: (A) MIL-53(Fe)+SA, (B) FeCl3+SA, (C) MIL-53(Fe). Inset: the corresponding photograph of different systems.

To further demonstrate the inhibitory effect of SA on the peroxidase-like activity of MIL-53(Fe), the production of hydroxyl radical (·OH) within the reaction was investigated. Electron spin resonance (ESR) spectroscopy was carried out with 5,5-dimethylpyrroline N-oxide (DMPO) as the ·OH trapping agent (Zhao et al., 2019). As depicted in Figure S2, it shows typical ·OH signals in the MIL-53(Fe)+H2O2 system. However, the signal intensity is obviously decreased with the addition of SA. To be specific, as Fe3+ ions in the center of MIL-53(Fe) are Fenton-like reagents, they can catalyze the decomposition of H2O2 into ·OH via a Fenton-type reaction (Yao et al., 2018). In the meantime, the redox cycle of Fe3+/Fe2+ is decelerated due to the complexation of SA to Fe3+. Consequently, the production of hydroxyl radical (·OH) in the reaction is decreased. This also proves that the catalytic activity of MIL-53(Fe) is inhibited by SA.

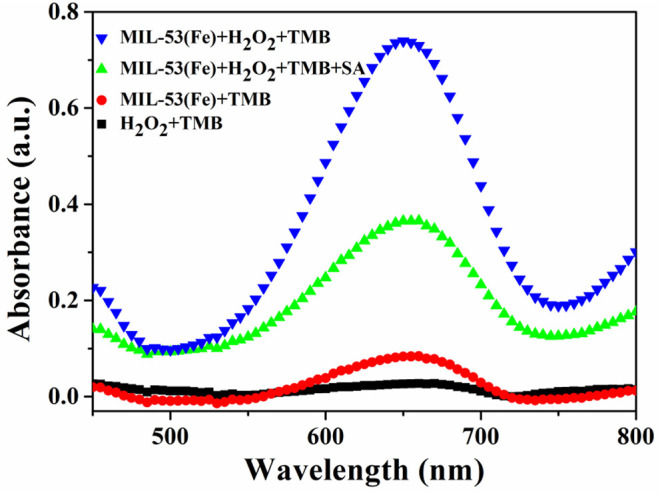

Feasibility of SA Detection by MIL-53(Fe) Nanozyme

A feasibility test for SA detection was performed and the result is displayed in Figure 4. Obviously, the highest absorption peak occurs when MIL-53(Fe), H2O2, and TMB are mixed and incubated together, this is ascribed to the potential peroxidase-like activity of the as-prepared MIL-53(Fe). Additionally, no obvious absorption peak can be observed during either of the two groups (the group of H2O2+TMB or MIL-53(Fe)+TMB). What is interesting, however, is that while SA is added to the MIL-53(Fe)/TMB/H2O2 system, the absorption peak intensity is decreased significantly. As we know, SA has good strong complexation ability to Fe3+ ions, thereby forming iron salicylate complexes. That might be the reason why SA has an effective inhibitory effect on the catalytic activity of MIL-53(Fe). In brief, the proposed colorimetric method is built on the inhibitory effect of SA on the inherent activity of the MIL-53(Fe) nanozyme.

Figure 4.

UV-Vis absorbance spectra on the feasibility analysis for the detection of SA based on the MIL-53(Fe) nanozyme.

Optimization of Experimental Conditions

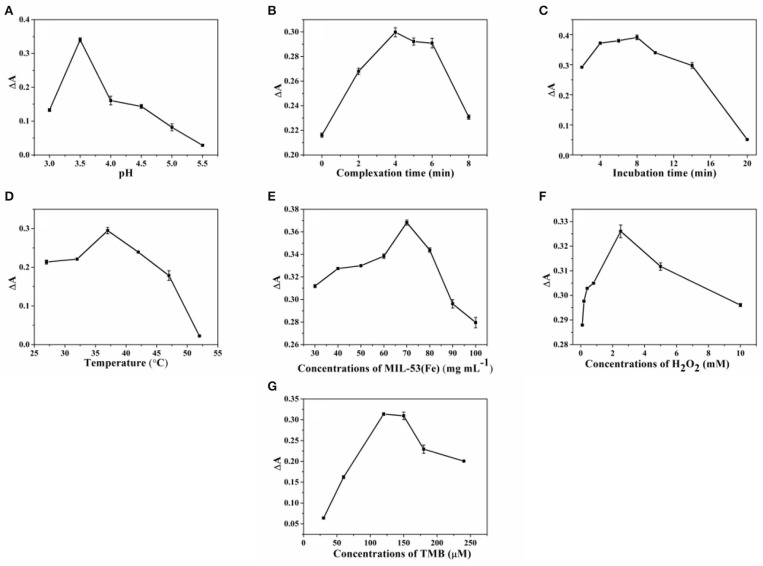

In realizing the best performance in SA detection, the influence of the experimental conditions, such as pH, complexation time, incubation time, temperature, and concentrations of MIL-53(Fe), H2O2, and TMB, were investigated. Since the activity of MIL-53(Fe) and the reaction of MIL-53(Fe) with SA are closely related to the pH value, therefore the effects of different pH values (3.0, 3.5, 4.0, 4.5, 5.0, and 5.5) were first studied. ΔA (A-A0, A, and A0 represent the absorbance of the system without or with SA, respectively), is used as the index to evaluate the best conditions for the detection of SA. As can be seen from Figure 5A, it is clear that the value of ΔA reaches a peak at pH 3.5. This can be explained by the fact that the activity of MIL-53(Fe) and the complexation ability of MIL-53(Fe) with SA is higher at pH 3.5. Consequently, 3.5 was chosen as the optimal pH value. Figures 5B,C clearly show that along with the increase of reaction time, the absorbance intensity (ΔA) starts to decrease after 4 and 8 min, indicating that 4 min was the most satisfactory time for MIL-53(Fe) to bind with SA and 8 min was the most suitable incubation time for the experiment. Moreover, the optimal temperature from 27 to 52°C was further discussed. As seen from Figure 5D, the value of ΔA declined dramatically as the temperature reached 37°C, hence, 37°C was considered as the optimal temperature for the reaction. Furthermore, the concentration of MIL-53(Fe) plays a key role in its catalytic activity. Figure 5E exhibits that with an increasing MIL-53(Fe) concentration, the ΔA value increased gradually until 70 μg L−1, showing that the concentrations of 70 μg L−1 of MIL-53(Fe) is sufficient for detecting SA. Additionally, Figures 5F,G depicted that TMB and H2O2 concentrations have an effect on the absorbance intensity. The value of ΔA reached the top as the concentrations of TMB and H2O2 increased to 120 μM and 2.5 mM, respectively. Overall, after optimization, 3.5, 4 min, 8 min, 37°C, 70 μg L−1, 120 μM, and 2.5 mM are shown to be the optimal pH value, complexation time, incubation time, temperature, and concentrations of MIL-53(Fe), H2O2, and TMB.

Figure 5.

The optimization of (A) pH, (B) complexation time, (C) incubation time, (D) temperature, and concentrations of (E) MIL-53(Fe), (F) H2O2, and (G) TMB for SA sensing. Error bars represent the standard deviation of the three trials.

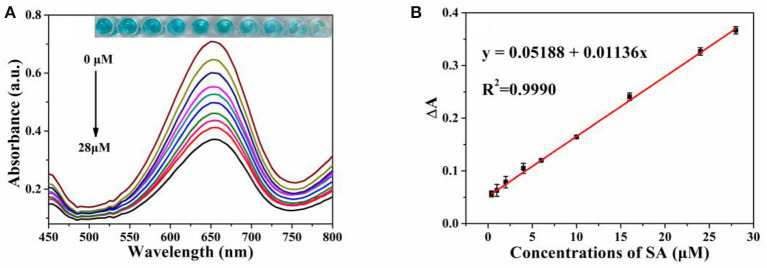

Colorimetric Detection of SA

Since the addition of SA can significantly inhibit the peroxidase-like activity of MIL-53(Fe), a colorimetric assay for the determination of SA was developed. Under the optimal experimental conditions, different concentrations of the SA solution were added to the MIL-53(Fe)/TMB/H2O2 system. Meanwhile, the mixed solution was detected and the obtained absorption spectrum was analyzed. Eventually, the limit of detection (LOD) was calculated by using the signal-to-noise ratio (S/N = 3) (He et al., 2018). As revealed by Figure 6A, absorbance intensities at 652 nm decreased gradually as the concentrations of SA increased from 0 to 28 μmol L−1, and the color change of oxTMB is visible to the naked eye. In the meantime, as depicted in Figure 6B, there was an excellent linear relationship between absorbance intensity (ΔA) and SA concentrations in the range of 0.4–28 μmol L−1 (R2 = 0.9990), and the LOD was calculated to be 0.26 μmol L−1. The Chinese Pharmacopeia (edition 2015), set a standard that the maximum limit of SA in aspirin is 0.3% (2.16 μmol L−1). Hence, the value of LOD (0.26 μmol L−1) was lower than the safety limits. Furthermore, the LOD value and linear ranges of our method are compared with those of other methods. As shown in Table S1, the sensitivity of our measurement was superior to most previously reported values, indicating that the established method was appropriate for SA detection.

Figure 6.

(A) The vis absorption spectra of MIL-53(Fe)-TMB-H2O2 upon concentrations of SA (from 0 to 28 μmol L−1). Inset: the corresponding photograph of the colored products; (B) The linear relationship between absorbance intensity (ΔA) and SA level. Error bars represent the standard deviation of three trials.

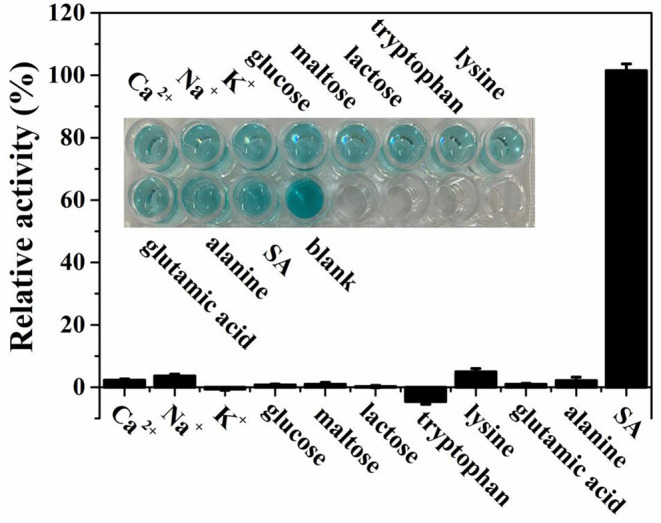

Selectivity of the Colorimetric Biosensor

In order to study the selectivity of our assay toward SA detection, possible coexisting substances including some metal ions, amino acids, and carbohydrates were used for investigating under the optimal experimental conditions. As demonstrated in Figure 7, obviously, only the species SA can induce a significant absorption intensity when the concentrations of SA and possible coexisting substances are both 28 μmol L−1. Additionally, as illustrated in the inset of Figure 7, there was no interference with the color change in the presence of other coexisting substances. All the results above show that the biosensor designed for colorimetric detection of SA was highly selective.

Figure 7.

Selectivity for SA detection with existence of several possible coexisting substances based on theMIL-53(Fe)-TMB-H2O2 system. The inset shows the corresponding photograph of the interference experiment.

Detection of SA in Aspirin Samples

To confirm the reliability of the developed platform for colorimetric detection of SA, the original amount of SA in aspirin was first measured by using the HPLC method (Figure S3), and the detection results were compared with those obtained by colorimetry. As displayed in Table 1, the detected SA concentrations by the proposed strategy have shown satisfactory agreement in comparison with the measured data from HPLC, the relative error was within 5%. Meanwhile, to further investigate the precision and practicability of our assay, a spike recovery test was carried out. As demonstrated by Table S2, it shows that a meaningful recovery of 91.0–101.4% was obtained and the value of RSD ranged from 2.0 to 4.2%. In a word, the results proved the potential of this proposed method in practical applications.

Table 1.

The recovery test of our assay for detecting SA in Pharmaceutical samples.

| Sample | Original amount (μM) | Spiked (μM) | Found (μM) | Recovery (%) | RSD (%, n = 3) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample 1 | 1.55 | 12 | 10.92 | 91.0 | 4.2 |

| 20 | 18.61 | 93.0 | 3.8 | ||

| Sample 2 | 2.37 | 10 | 9.97 | 99.7 | 3.0 |

| 14 | 13.7 | 98.0 | 4.0 | ||

| Sample 3 | 3.83 | 8 | 8.11 | 101.4 | 2.0 |

| 16 | 15.39 | 96.2 | 3.5 |

Conclusions

In this study, we confirmed that the obtained MIL-53(Fe) possessed inherent peroxidase-mimicking activity, as they were equipped to catalyze the oxidation of chromogenic TMB in the presence of H2O2. Meanwhile, based on the strong complexing action between the Fe3+ in the center of MIL-53(Fe) and SA, the activity of MIL-53(Fe) can be effectively inhibited with the addition of SA, causing fewer hydroxyl radicals to be produced in the system to decelerate the oxidation of TMB. The experimental results clearly displayed that a lighter color for the oxTMB can be observed with naked eye. By combining the peroxidase-mimicking properties of MIL-53(Fe) and the inhibitory effect of SA on its activity, a colorimetric sensing platform for the detection of SA was established. The developed colorimetric method not only has excellent accuracy in detecting SA in aspirin compared with HPLC but also shows high selectivity and sensitivity to SA. In summary, the proposed method can be well-utilized for detecting SA in aspirin. Furthermore, the present work displays the great potential of using MOFs nanozymes for pharmaceutical analysis.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Author Contributions

LL: conceptualization, methodology, data curation, investigation, and writing original draft. YH: conceptualization, methodology, data curation, and investigation. WL: data curation and investigation. WZ: investigation. FY: visualization, resources, funding acquisition, supervision, project administration, writing—review, and editing. SZ: funding acquisition and project administration. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Funding. This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundations of China (21765002), Guangxi Natural Science Foundation of China (2017GXNSFDA198044), and the BAGUI Scholar Program.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fchem.2020.00671/full#supplementary-material

References

- Aboul-Soud M. A. M., Cook K., Loake G. J. (2004). Measurement of salicylic acid by a high-performance liquid chromatography procedure based on ion-exchange. Chromatographia 59, 129–133. 10.1365/s10337-003-0136-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ai L. H., Li L. L., Zhang C. H., Fu J., Jiang J. (2013). MIL-53(Fe): a metal-organic framework with intrinsic peroxidase-like catalytic activity for colorimetric biosensing. Chem. Eur. J. 19, 15105–15108. 10.1002/chem.201303051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bodek M., Burch M., Cannon J., Finneran D., Geveke K., Sinkinson H., et al. (2020). Revisiting the determination of percent aspirin lab: using a limiting reactant approach for students to also determine the amount of iron (III) chloride. J. Chem. Educ. 97, 574–577. 10.1021/acs.jchemed.9b00154 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chanakul A., Traiphol R., Traiphol N. (2016). Colorimetric sensing of various organic acids by using polydiacetylene/zinc oxide nanocomposites: effects of polydiacetylene and acid structures. Colloids Surf. A 489, 9–18. 10.1016/j.colsurfa.2015.09.068 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chang Y. H., Huang C. W., Fu S. F., Wu M. Y., Wu T., Lin Y. W. (2017). Determination of salicylic acid using a magnetic iron oxide nanoparticle-based solid-phase extraction procedure followed by an online concentration technique through micellar electrokinetic capillary chromatography. J. Chromatogr. A 1479, 62–70. 10.1016/j.chroma.2016.12.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen C., Feng S., Zhou M., Ji C., Que L., Wang W. (2019). Development of a structure-switching aptamer-based nanosensor for salicylic acid detection. Biosens. Bioelectron 140:111342. 10.1016/j.bios.2019.111342 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collado S., Garrido L., Laca A., Diaz M. (2010). Wet oxidation of salicylic acid solutions. Environ. Sci. Technol. 44, 8629–8635. 10.1021/es1021944 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Croubels S., Maes A., Baert K., De Backer P. (2005). Quantitative determination of salicylic acid and metabolites in animal tissues by liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry. Anal. Chim. Acta 529, 179–187. 10.1016/j.aca.2004.08.020 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dahl J. B., Kehlet H. (1991). Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs: rationale for use in severe postoperative pain. Br. J. Anaesth. 66, 703–712. 10.1093/bja/66.6.703 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan S., Zhao M., Ding L., Li H., Chen S. (2017). Preparation of Co3O4/crumpled graphene microsphere as peroxidase mimetic for colorimetric assay of ascorbic acid. Biosens. Bioelectron. 89, 846–852. 10.1016/j.bios.2016.09.108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Floková K., Tarkowská D., Miersch O., Strnad M., Wasternack C., Novák O. (2014). UHPLC–MS/MS based target profiling of stress-induced phytohormones. Phytochemistry 105, 147–157. 10.1016/j.phytochem.2014.05.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hao Y., Xiong D., Wang L., Chen W., Zhou B., Liu Y. N. (2013). A reversible competition colorimetric assay for the detection of biothiols based on ruthenium-containing complex. Talanta 115, 253–257. 10.1016/j.talanta.2013.04.076 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He Y. F., Li X., Xu X. C., Pan J. M., Niu X. H. (2018). A cobalt-based polyoxometalate nanozyme with high peroxidase-mimicking activity at neutral pH for one-pot colorimetric analysis of glucose. J. Mater. Chem. B 6, 5750–5755. 10.1039/C8TB01853G [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu Y., Wang X., Wang C., Hou P., Dong H., Luo B. (2020). A multifunctional ratiometric electrochemical sensor for combined determination of indole-3-acetic acid and salicylic acid. RSC Adv. 10, 3115–3121. 10.1039/C9RA09951D [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Z. H., Wang Z. L., Shi B. L., Wei D., Chen J. X., Wang S. L., et al. (2015). Simultaneous determination of salicylic acid, jasmonic acid, methyl salicylate, and methyl jasmonate from ulmus pumila leaves by GC-MS. Int. J. Anal. Chem. 2015:698630. 10.1155/2015/698630 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kopp E., Ghosh S. (1994). Inhibition of NF-kappa B by sodium salicylate and aspirin. Science 265, 956–959. 10.1126/science.8052854 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Z. M., Zhong X. L., Wen S. H., Zhang L., Liang R. P., Qiu J. D. (2019). Colorimetric detection of methyltransferase activity based on the enhancement of CoOOH nanozyme activity by ssDNA. Sens. Actuators B 281, 1073–1079. 10.1016/j.snb.2018.11.085 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lin T. R., Qin Y. M., Huang Y. L., Yang R. T., Hou L., Ye F. G., et al. (2018). A label-free fluorescence assay for hydrogen peroxide and glucose based on the bifunctional MIL-53 (Fe) nanozyme, Chem. Commun. 54, 1762–1765. 10.1039/C7CC09819G [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin Z., Zhang X. M., Liu S. J., Zheng L. L., Bu Y. M., Deng H. H., et al. (2020). Colorimetric acid phosphatase sensor based on MoO3 nanozyme. Anal. Chim. Acta. 1105, 162–168. 10.1016/j.aca.2020.01.035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marques T. L., Moraes L. M. B., Rocha F. R. P. (2020). Systematic evaluation of sample preparation for fractionation of phytohormone salicylic acid in fresh leaves. Talanta 208:120352. 10.1016/j.talanta.2019.120352 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Millange F., Guillou N., Medina M. E., Férey G., Carlin-Sinclair A., Golden K. M., et al. (2010). Selective sorption of organic molecules by the flexible porous hybrid metal-organic framework MIL-53(Fe) controlled by various host-guest interactions. Chem. Mater. 22, 4237–4245. 10.1021/cm1008587 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Parham H., Rahbar N. (2009). Solid phase extraction-spectrophotometric determination of salicylic acid using magnetic iron oxide nanoparticles as extractor. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 50, 58–63. 10.1016/j.jpba.2009.03.037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shokrollahi A., Mohammadpour Z., Abbaspour A. (2017). Colorimetric determination of free salicylic acid in aspirin and urine by scanometry as a new, reliable, inexpensive and simple method. Pharm. Chem. J. 51, 324–329. 10.1007/s11094-017-1607-2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Song C., Ding W., Zhao W., Liu H. B., Wang J., Yao Y. W., et al. (2020). High peroxidase-like activity realized by facile synthesis of FeS2 nanoparticles for sensitive colorimetric detection of H2O2 and glutathione. Biosens. Bioelectron 151:111983. 10.1016/j.bios.2019.111983 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanchev S., Ioncheva N., Genov N., Malchev E. (1980). Gas chromatographic identification of phenolic acids found in sweet cherry and sour cherry juice. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 24, 251–253. 10.1002/food.19800240307 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tian M., Adams B., Wen J., Asmussen R. M., Chen A. (2009). Photoelectrochemical oxidation of salicylic acid and salicylaldehyde on titanium dioxide nanotube arrays. Electrochim. Acta 54, 3799–3805. 10.1016/j.electacta.2009.01.077 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tseng P. J., Wang C. Y., Huang T. Y., Chuang Y. Y., Fu S. F., Lin Y. W. (2014). A facile colorimetric assay for determination of salicylic acid in tobacco leaves using titanium dioxide nanoparticles. Anal. Methods 6, 1759–1765. 10.1039/C3AY42209G [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Uddin N., Krieg C., Stöggl W., Stecher G., Abel G., Popp M., et al. (2014). Quantitative analysis of salicylic acid and its derivatives in primulae radix by high performance liquid chromatography-diode array detection-electrospray ionization mass spectrometry (HPLC-DAD-ESI-MS) and simultaneous determination of total polyphenol content (TPC). Curr. Anal. Chem. 10, 271–279. 10.2174/15734110113099990015 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J., Hu Y. Y., Zhou Q., Hu L. Z., Fu W. S., Wang Y. (2019b). Peroxidase-like activity of metal-organic framework [Cu(PDA)(DMF)] and its application for colorimetric detection of dopamine. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 11, 44466–44473. 10.1021/acsami.9b17488 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang P. Y., Luo X., Yang L. L., Zhao Y. C., Dong R., Li Z., et al. (2019a). A rhodamine-based highly specific fluorescent probe for the in situ and in vivo imaging of the biological signalling molecule salicylic acid. Chem. Commun. 55, 7691–7694. 10.1039/C9CC03094H [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z., Ai F., Xu Q., Yang Q., Yu J. H., Huang W. H., et al. (2010). Electrocatalytic activity of salicylic acid on the platinum nanoparticles modified electrode by electrochemical deposition. Colloids Surf. B 76, 370–374. 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2009.10.038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiong Y. H., Chen S. H., Ye F. G., Su L. J., Zhang C., Shen S. F., et al. (2015). Synthesis of a mixed valence state Ce-MOF as an oxidase mimetic for the colorimetric detection of biothiols. Chem. Commun. 51, 4635–4638. 10.1039/C4CC10346G [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan Z., Yuan H., Zhao Q., Xing L., Zheng X., Wang W., et al. (2020). Recent developments of nanoenzyme-based colorimetric sensors for heavy metal detection and the interaction mechanism. Analyst 145, 3173–3187. 10.1039/D0AN00339E [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao C., Wang W. X., Wang P. Y., Zhao M. Y., Li X. M., Zhang F. (2018). Near-infrared upconversion mesoporous cerium oxide hollow biophotocatalyst for concurrent pH-/H2O2-Responsive O2-evolving synergetic cancer therapy. Adv. Mater. 30:1704833. 10.1002/adma.201704833 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y., Dai C. L., Liu W., Wang Y. Y., Ding F., Zou P., et al. (2019). Ultrathin films of a metal-organic framework prepared from 2-methylimidazole, manganese(II) and cobalt(II) with strong oxidase-mimicking activity for colorimetric determination of glutathione and glutathione reductase activity. Microchim. Acta 186, 1–9. 10.1007/s00604-019-3434-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y., Zhang W. T., Chen K., Yang Q. F., Hu N., Suo Y. R., et al. (2018). Highly sensitive and selective colorimetric detection of glutathione via enhanced fenton-like reaction of magnetic metal organic framework. Sens. Actuators B 262, 95–101. 10.1016/j.snb.2018.01.221 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao P. R., Tang Z. M., Chen X. Y., He Z. Y., He X. H., Zhang M., et al. (2019). Ferrous-cysteine-phosphotungstate nanoagent with neutral pH fenton reaction activity for enhanced cancer chemodynamic therapy. Mater. Horiz. 6, 369–374. 10.1039/C8MH01176A [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.