Abstract

This study aimed to identify novel long noncoding RNA (lncRNA) biomarkers for hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) using publicly available tissue genomic datasets and validate their diagnostic utility for early‐stage HCC. Differentially expressed lncRNAs between 371 HCC and 50 nontumor tissues were obtained from The Cancer Genome Atlas liver hepatocellular carcinoma (TCGA_LIHC) project. Subsequently, the expression of the serum‐ and extracellular vesicle (EV)‐derived lncRNA was assessed in 10 patients with HCC and 10 healthy controls using RT–qPCR. The candidate lncRNAs were validated in 90 HCC and 92 non‐HCC (29 healthy control, 28 chronic hepatitis, 35 liver cirrhosis) patients. The sensitivity, specificity, and area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC) were calculated for the candidate lncRNAs and the current HCC biomarker, alpha‐fetoprotein (AFP). SFTA1P, HOTTIP, HAGLROS, LINC01419, HAGLR, CRNDE, and LINC00853 were markedly upregulated in HCC in TCGA_LIHC dataset. Among them, LINC00853 has not been reported in relation to HCC before. In patients with HCC, only expression of small EV‐derived LINC00853 (EV‐LINC00853) was increased. EV‐LINC00853 showed excellent discriminatory ability in the diagnosis of all‐stage HCC (AUC = 0.934, 95% confidence interval = 0.887–0.966). Moreover, using a 14‐fold increase and 20 ng·mL−1 as cutoffs for EV‐LINC00853 expression and AFP level, respectively, EV‐LINC00853 was found to have a sensitivity of 93.75% and specificity of 89.77%, while AFP showed only 9.38% sensitivity and 72.73% specificity for the diagnosis of early‐stage HCC (mUICC stage I). EV‐LINC00853 had a positivity of 97% and 67% in AFP‐negative and AFP‐positive early HCC, respectively. Serum EV‐derived LINC00853 may be a novel potential diagnostic biomarker for early HCC, especially for AFP‐negative HCC.

Keywords: biomarker, extracellular vesicles, hepatocellular carcinoma, LINC00853, long noncoding RNA

Long noncoding RNA (lncRNA) dysregulation has been observed in several cancers, including liver cancer. Here, we show that extracellular vesicle (EV)‐derived lncRNA EV‐LINC00853 showed high sensitivity and specificity for diagnosis of early HCC. EV‐LINC00853 is a potential diagnostic biomarker for early HCC, especially for AFP‐negative HCC.

![]()

Abbreviations

- AFP

alpha‐fetoprotein

- ANOVA

one‐way analysis of variance

- AUC

area under the curve

- CH

chronic hepatitis

- CI

confidence interval

- EDS

extracellular vesicle‐depleted serum

- EV

extracellular vesicle

- HCC

hepatocellular carcinoma

- LC

liver cirrhosis

- lncRNA

long noncoding RNA

- mUICC

modified Union for International Cancer Control

- NTA

nanoparticle tracking analysis

- ROC

receiver operating characteristic

- RT–qPCR

quantitative reverse transcription PCR

- SD

standard deviation

- TCGA_LIHC

The Cancer Genome Atlas liver hepatocellular carcinoma

- TEM

transmission electron microscopy

1. Introduction

Liver cancer is the sixth most prevalent cancer and fourth most common cause of cancer‐related death globally; the high mortality rate is mainly due to the late diagnosis and poor response to therapy [1]. Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) accounts for ~ 90% of the primary liver cancers and represents a major global health problem. Approximately 90% of the HCCs are associated with a known underlying etiology, most frequently chronic viral hepatitis B or C, excessive alcohol intake, or aflatoxin exposure [2]. Individuals at high risk of developing HCC are recommended to undergo abdominal ultrasonography every 6 months [3]. However, ultrasonography has only a sensitivity of 63% for detecting early‐stage HCC [4]. Alpha‐fetoprotein (AFP), which is the most widely used blood biomarker in HCC, also shows suboptimal performance as a serological test in HCC surveillance because of fluctuations in the AFP levels during hepatitis flares and 10–20% positivity in early‐stage HCC [5]. Therefore, there is an urgent need to develop better screening tools and diagnostic tests for diagnosis of early‐stage HCC to improve the prognosis of patients with this fatal disease.

Long noncoding RNAs (lncRNAs) are referred transcripts having a lengths exceeding 200 nucleotides that do not encode proteins in general; they are related to various functions, including regulation of transcription in cis or trans, modulation of messenger RNA (mRNA) processing, post‐translational control of protein activity, and organization of nuclear domains [6, 7]. Many lncRNAs have been functionally associated with human diseases [8], and their dysregulation has been observed in several cancers, including liver cancer [9, 10, 11]. Altered lncRNA expression can contribute to cancer phenotypes by stimulating cellular proliferation, angiogenesis, immune evasion, metastasis, and inhibiting apoptosis [8, 12].

Small extracellular vesicles (EVs; < 100 nm) play key roles in numerous normal and pathological biological processes [13]. Small EVs transfer proteins, DNA, and various forms of RNA, such as microRNA (miRNA), lncRNA, and mRNA, between tumor and nontumor cells [14]. Various EV‐derived lncRNAs, including lncRNA‐HEIH, LINC02394, LINC0635, LINC00161, and JPX [15, 16, 17, 18], were recently reported as diagnostic biomarkers for HCC. However, research into the diagnostic potential of lncRNAs in HCC has been limited by small sample sizes and unsatisfactory diagnostic performance for early‐stage HCC.

The present study aimed to identify novel HCC‐related lncRNAs using publicly available tissue genomic datasets and validate their diagnostic performance for early‐stage HCC in a moderately large cohort of patients with different liver diseases.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Resources of publicly available genomic data

To investigate the expression of lncRNA biomarkers in HCC, genomic data were acquired from The Cancer Genome Atlas liver HCC project (TCGA_LIHC, https://cancergenome.nih.gov) and the GEO database of the NCBI (Accession Numbers: GSE94660, GSE114584, and GSE124535). The expression data for each lncRNA were log2 transformed [log2(FPKM + 1)] for downstream analyses.

2.2. Gene set enrichment analysis

To investigate gene signatures that were enriched from known molecular databases, we downloaded gene sets from MSigDB (http://software.broadinstitute.org/gsea/msigdb) at the Broad Institute Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (http://www.broadinstitute.org/gsea).

2.3. Patient enrollment and clinical term definitions

Patients were enrolled from the Ajou University Hospital, Suwon, South Korea, between January 2014 and December 2018. The study subjects were allocated into one of four groups: healthy control, chronic hepatitis (CH), liver cirrhosis (LC), and HCC. A healthy control was defined as an individual between 18 and 50 years of age without any medical history, who visited the Ajou Health Promotion Center for health check‐up. CH was diagnosed based on the persistence of serum hepatitis B surface antigen or hepatitis C virus RNA for more than 6 months. LC was diagnosed based on ultrasonographic findings including splenomegaly, blunt angle, and morphological changes [19]. HCC was diagnosed if tumor had a maximum diameter > 1 cm and characteristic features of HCC (arterial phase hyperenhancement, washout in the portal venous or delayed phase, threshold growth, and capsule appearance) in multiphase computed tomography and/or magnetic resonance imaging. If these criteria were present but there was a lack of diagnostic certainty, then a liver biopsy was performed to confirm the diagnosis of HCC [20]. Early‐stage HCC was defined as a single lesion less than 2 cm in diameter corresponding to the modified Union for International Cancer Control (mUICC) stage I. The test cohort consisted of 10 patients with HCC and 10 healthy controls, and the validation cohort consisted of 90 patients with HCC and 92 patients without HCC (29 healthy controls, 28 with CH, and 35 with LC). Patients whose AFP level measurements were unavailable were excluded from the comparative analysis. Overall survival was defined as the time from HCC diagnosis to death resulting from any causes. All investigations performed in the present study were conducted in accordance with the guidelines of the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki. The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Ajou University Hospital, Suwon, South Korea (AJRIB‐BMR‐KSP‐18‐397 and AJIRB‐BMR‐KSP‐18‐299). Anonymous serum samples and clinical data were provided by the Ajou Human Bio‐Resource Bank. Informed consent was waived.

2.4. Cell culture

Huh7 cells (Korean Cell Line Bank, Seoul, Korea) were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (GenDEPOT, Barker, TX, USA) supplemented with 10% FBS (Invitrogen, Waltham, MA, USA) and 100 U·mL−1 penicillin–streptomycin (GenDEPOT), at 37° C in a humidified incubator with 5% CO2.

2.5. Separation of blood serum

Five milliliters of blood was collected from each individual directly into serum collection tubes. The blood was centrifuged at 1800 g for 10 min to extract the serum, which was aliquoted into 1.5‐mL tubes and stored at −80 °C. The serum samples were centrifuged at 3000 g at 4 °C for 15 min to remove cell debris before analysis.

2.6. Characterization of serum small EVs

Small EVs were extracted from the serum using ExoQuick (System Biosciences, Mountain View, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer's instructions with minor modifications [21]. Briefly, serum samples (300 μL) were mixed with ExoQuick (72 μL) and incubated at 4 °C overnight. The mixtures were then centrifuged at 1500 g for 30 min at room temperature. The supernatants were collected and used as EV‐depleted serum (EDS), whereas the pellets were resuspended in PBS (100 μL) and stored at −80 °C for subsequent extraction of RNA and proteins.

Transmission electron microscopy (TEM), nanoparticle tracking analysis (NTA), and western blotting were performed to confirm the presence and size of small EVs. For TEM, small EVs were marked with 10‐nm gold particles conjugated to anti‐CD63 antibody. Sample fixation was performed with 2% glutaraldehyde and 4% paraformaldehyde for 2 h at room temperature, and the EVs were inspected under a Sigma 500 electron microscope (Carl Zeiss, Jena, Germany). The size and quantity of the isolated EVs were examined using the NanoSight NS300 instrument (Malvern Panalytical Ltd., Malvern, UK) equipped with a 405 nm laser. A 60‐s video was recorded with a frame rate of 30 frames/s, and the particle movement was evaluated using nta software (version 3.0, Malvern Panalytical). Each sample was analyzed three times, and the counts were merged.

For western blotting, EDS, serum derived‐small EVs, and Huh7 total cell lysate were lysed in RIPA lysis buffer (100 μL; Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) and incubated on ice for 10 min. Total protein concentration was quantified by the bicinchoninic acid assay (Thermo Scientific). The proteins (10 μg) were separated on 4–20% Mini‐PROTEAN TGX™ gels (Bio‐Rad, Hercules, CA, USA) and then transferred to poly(vinylidene difluoride) membranes (Amersham; GE Healthcare, Munich, Germany). The membranes were blocked in 5% nonfat milk in TBS‐T and immunoblotted using the following primary antibodies: mouse anti‐CD81 (1 : 250; 10630D; Invitrogen), rabbit anti‐CD9 (1 : 2000; ab92726; Abcam, Cambridge, UK), mouse anti‐ALIX (1 : 1000; sc‐53538; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas, TX, USA), mouse anti‐HSP90 (1 : 1000; SMC‐149; StressMarq Biosciences Inc., Victoria, BC, Canada), mouse anti‐BiP/GRP78 (1 : 1000; 610979; BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA), and rabbit anti‐APOA1 (1 : 1000; ab52945; Abcam). The samples were then probed with secondary HRP‐conjugated anti‐rabbit (BR170‐6515; Bio‐Rad) or anti‐mouse (BR170‐6516; Bio‐Rad) antibodies.

2.7. Isolation of serum RNA and small EV‐derived RNA from peripheral blood samples from patients

RNA from serum‐derived EVs was extracted using the SeraMir™ Exosome RNA Amplification Kit (System Biosciences) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Briefly, serum samples (300 μL) were mixed with ExoQuick solution (72 μL) and incubated at 4 °C overnight. The mixtures were centrifuged at 1500 g for 30 min at room temperature before the supernatants were removed and the pellets resuspended in PBS (100 μL). The EV lysates were mixed with lysis buffer (300 μL) and 100% EtOH (200 μL). After vortexing for 10 s, the mixtures were transferred to a spin column and centrifuged at 15 928 g for 1 min and then washed twice with wash buffer (400 μL). After further centrifugation for 2 min, small EV‐derived RNA was eluted in elution buffer (30 μL).

Serum RNA was isolated using the TRIzol‐LS reagent (Invitrogen). In brief, serum (300 μL) was lysed in TRIzol‐LS (900 μL) before the RNA was phase separated using chloroform (240 μL), precipitated with 100% isopropanol, and washed in 75% EtOH. Finally, the RNA was eluted in RNase‐free water (30 μL).

The RNA concentration was assessed using the NanoDrop 2000 spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific), while its yield and size distribution were analyzed using the Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer and RNA 6000 Nano kit (Agilent Technologies, Foster City, CA, USA).

2.8. Quantitative reverse transcription PCR (RT–qPCR)

The expression level of the serum‐derived and the serum small EV‐derived lncRNA was measured using RT–qPCR. Serum RNA (500 ng) was reverse transcribed into complimentary DNA (cDNA) using the PrimeScript™ RT Master mix (TaKaRa Bio, Otsu, Japan), whereas small EV‐derived RNA (500 ng) was reverse transcribed using the miScript II RT kit (QIAGEN, Hilden, Germany). The resultant cDNAs were used as templates for RT–qPCR with the amfiSure qGreen Q‐PCR Master Mix (GenDEPOT), which was monitored in real time using the ABI 7300 Real‐Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems™, Foster City, CA, USA). PCR conditions were as follows: 15 s at 95 °C for denaturation, 34 s at 60 °C for primer annealing, and 30 s at 72 °C for primer extension. The following primer pairs were used as follows: LINC00853 forward: AAAGGCTAGGCGATCCCACA, reverse: ACTCCCTAGCTTGGCTCTCCT; HMBS forward: GGAGGGCAGAAGGAAGAAAACAG, reverse: CACTGTCCGTCTGTATGCGAG. The method was used to determine target gene expression relative to the internal control gene, HMBS. Relative LINC00853 levels were calculated using , where ΔCt = Ct (LINC00853) − Ct (HMBS) and ΔΔCt = ΔCt (individual samples) − ΔCt (mean of normal samples). All measurements were performed in triplicate.

2.9. Statistical analysis

The data are presented as mean ± SD of three experiments. All statistical analyses were performed in IBM spss version 22.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) and graphpad prism version 7.01 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA). For numerical variables, one‐way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Tukey's post hoc analysis was used to perform multiple comparisons between the three groups. The associations between categorical parameters were assessed using the two‐sided chi‐square test. Survival curves were plotted using the Kaplan–Meier method, and significant differences between the curves were determined using log‐rank test. P values < 0.05 were considered to be statistically significant. Each candidate biomarker accuracy for HCC was assessed by the area under the curve (AUC), sensitivity, and specificity based on receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves analysis. The Youden index was used to determine optimal cutoff values.

3. Results

3.1. Selection of candidate HCC‐associated lncRNAs

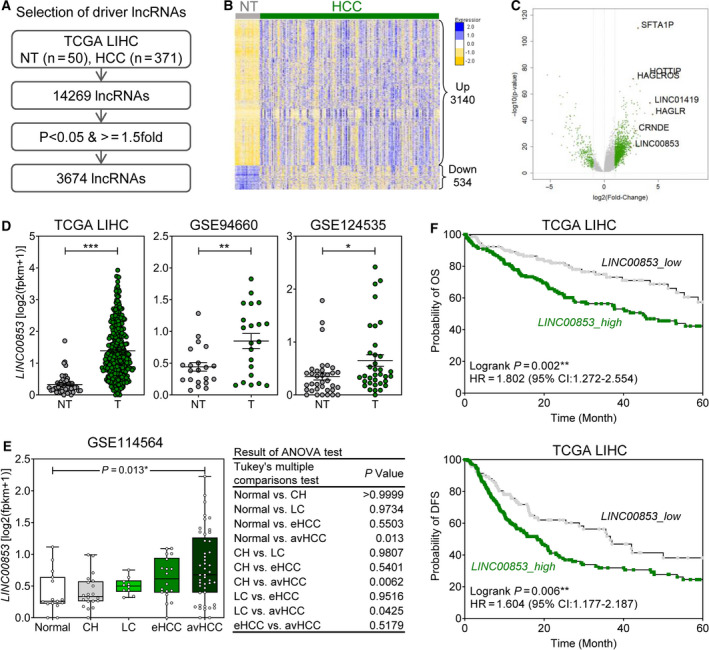

In order to identify novel lncRNAs that play key roles in the development of HCC, we analyzed the publicly available lncRNA profiles of 371 HCC and 50 surrounding nontumor tissues from TCGA‐LIHC dataset (Fig. 1A). Among the 14 269 lncRNAs, 3674 were significantly differentially expressed between the HCC and nontumor specimens (P < 0.05 and ≥ 1.5‐fold change). Specifically, 3140 lncRNAs were upregulated while 534 lncRNAs were downregulated in HCC (Fig. 1B). Volcano plot analysis identified seven distinctly upregulated lncRNAs (SFTA1P, HOTTIP, HAGLROS, LINC01419, HAGLR, CRNDE, and LINC00853; Fig. 1C). According to a review of the literature (Table S1), we propose that LINC00853 as a novel HCC‐related lncRNA that has not been reported thus far. We verified the expression of LINC00853 in publicly available HCC RNA‐Seq datasets (TCGA_LIHC, GSE94660, GSE124535, and GSE114564) and found that it was not only consistently overexpressed in HCC in all three datasets, but also that its expression increased with the progression of liver disease to HCC (Fig. 1D, 1E, P = 0.0017). The remaining six lncRNAs were also significantly overexpressed in HCC (Fig. S1). Survival analysis based on LINC00853 expression in TCGA_LIHC dataset showed that high LINC00853 expression was associated with poor overall survival and disease‐free survival (Fig. 1F, log‐rank P = 0.002, P = 0.006, respectively).

Fig. 1.

Correlation between clinical findings and LINC00853 overexpression in HCC cohorts. (A) The strategy to identify novel lncRNA markers for HCC. (B) Heatmap of 3674 HCC‐associated lncRNA signatures in the TCGA_LIHC dataset. (C) Volcano plot representation of differentially expressed lncRNA signatures in the nontumor and the HCC cohorts. (D) LINC00853 expression in the nontumor and the HCC cohorts in three HCC RNA‐Seq datasets (TCGA_LIHC, GSE94660, and GSE124535). Welch's t‐test; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001. (E) Changes in expression of 10 candidate marker genes in patients with different types and severity of liver disease in GSE114564 dataset. Statistically significant differences were determined using one‐way ANOVA with Tukey's multiple comparisons test. (F) The Kaplan–Meier survival curves for overall survival (left) and disease‐free survival (right) based on LINC00853 expression in patients with HCC in TCGA_LIHC dataset.

3.2. Expression of LINC00853 in the serum and serum small EVs in the test cohort

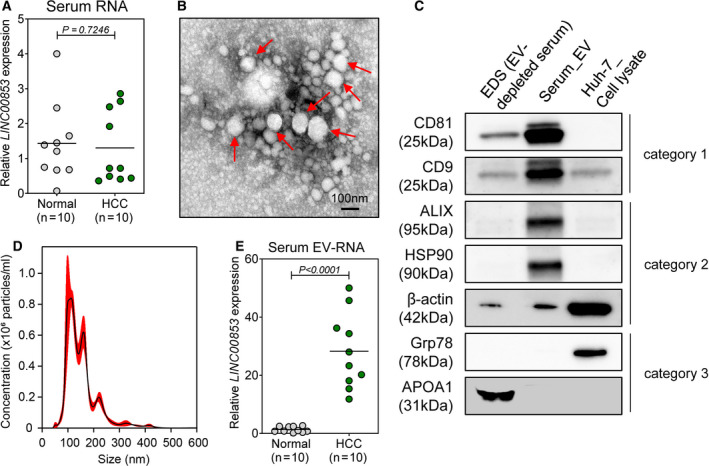

To evaluate the utility of LINC00853 as a noninvasive diagnostic marker for HCC, we measured LINC00853 expression in the serum (Fig. 2A) and serum EVs of 10 healthy controls and 10 patients with HCC. After separation from the serum, the EVs were characterized using TEM (Fig. 2B), immunoblotting for positive and negative protein markers of EV (Fig. 2C), and NTA (Fig. 2D). RT–qPCR analysis revealed that the level of serum‐derived LINC00853 was similar in the two groups (Fig. 2A, P = 0.7246), whereas that of the serum EV‐derived LINC00853 (EV‐LINC00853) was significantly higher in patients with HCC than in healthy controls (Fig. 2E, P < 0.001).

Fig. 2.

Expression of LINC00853 in patient serum samples and serum‐derived EVs. (A) Scatter plot of LINC00853 expression in the sera of healthy subjects (n = 10) and patients with HCC (n = 10). Statistically significant differences were determined using Welch's t‐test. Black horizontal lines denote means. (B) TEM image showing the spherical morphology of the isolated small EVs (diameter = ~ 100 nm), bar = 100 nm. (C) Representative immunoblots showing the expression of EV markers in the isolated EVs, according to MISEV 2018 guidelines. EDS and Huh‐7 cell lysate were used as controls. (D) The concentration and size distribution of EVs in the serum of a patient with HCC, as determined by NTA. (E) Scatter plot of LINC00853 expression in serum‐derived EVs of healthy subjects (n = 10) and patients with HCC (n = 10). Statistically significant differences were determined using Welch's t‐test. Black horizontal lines denote sample means. Target gene expression was calculated relative to that of HMBS.

3.3. Validation of EV‐LINC00853 as a diagnostic biomarker for HCC

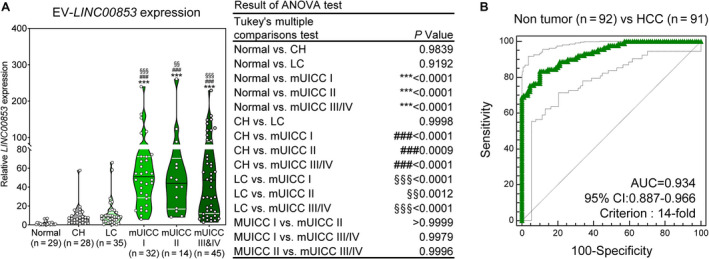

A total of 90 patients with HCC and 89 patients without HCC were enrolled to validate the diagnostic performance of EV‐LINC00853 for HCC. Demographic and clinical parameters of all subjects are listed in Table 1. The most common etiology of CH, LC, and HCC was hepatitis B virus. The percentage of patients with mUICC stage I, II, III, IVA, and IVB tumors was 35%, 16%, 29%, 12%, and 8%, respectively. The expression of EV‐LINC00853 was significantly higher in patients with HCC compared to that in healthy controls, patients with CH, and patients with LC (Fig. 3A). ROC curve analysis revealed that EV‐LINC00853 had excellent discriminatory ability [AUC = 0.934, 95% confidence interval (CI) = 0.887–0.966] in the diagnosis of HCC. The optimal cutoff value for the change in EV‐LINC00853 expression was 14‐fold (Fig. 3B ). Considering the uneven age distribution between the groups, we tested whether EV‐LINC00853 expression could vary depending on patient age. EV‐LINC00853 expression was comparable between different age groups (Fig. S2).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of patients selected for the validation cohort. Values are expressed as number (%) or mean ± SD.

| Variables | Validation cohort (N = 182) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Normal (n = 29) | CH (n = 28) | LC (n = 35) | HCC (n = 90) | |

| Age (years) | 34.4 ± 7.7 | 46.1 ± 10.7 | 53.5 ± 10.5 | 55.1 ± 9.0 |

| Male sex | 4 (13.8) | 15 (51.7) | 20 (58.8) | 71 (78.0) |

| Aspartate transaminase, IU·mL−1 | 16.62 ± 3.80 | 54.82 ± 52.25 | 82.29 ± 98.06 | 72.67 ± 96.80 |

| Alanine transaminase, IU·mL−1 | 13.86 ± 7.87 | 67.38 ± 78.21 | 78.14 ± 98.10 | 47.92 ± 58.98 |

| Platelet, ×109/L | 317 ± 35.84 | 185.15 ± 47.19 | 128.70 ± 76.64 | 166.41 ± 83.70 |

| AFP, ng·mL−1 | 1.78 ± 0.68 | 16.65 ± 24.30 | 65.88 ± 132.93 | 4246.40 ± 14450.97 |

| Etiology, hepatitis B virus/hepatitis C virus/alcohol/others | 27 (96.4)/1 (3.6)/0/0 | 30 (85.7)/3 (8.6)/2 (5.7)/0 | 82 (91.1)/4 (4.5))/3 (3.3)/1 (1.1) | |

| Albumin, g·L−1 | 4.55 ± 0.42 | 4.01 ± 0.53 | 4.26 ± 0.57 | |

| Bilirubin, mg·dL−1 | 0.82 ± 0.32 | 1.06 ± 0.99 | 1.39 ± 3.54 | |

| International normalized ratio | 1.17 ± 0.23 | 1.20 ± 0.10 | 1.49 ± 1.89 | |

| Modified Union for International Cancer Control stage, I/II/III/IVa/IVb | 32 (35)/14 (16)/26 (29) /11 (12)/ 7 (8) | |||

Fig. 3.

Expression of EV‐LINC00853 and its diagnostic performance in the validation cohort. (A) Violin plot of EV‐LINC00853 expression, as measured by RT–qPCR. Statistically significant differences were determined using the one‐way ANOVA with Tukey's multiple comparisons test. Black horizontal lines denote means, and error bars represent SEM. Compared to healthy liver; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, compared to CH; #P < 0.05, ##P < 0.01, ###P < 0.001, compared to LC; §P < 0.05, §§P < 0.01, §§§P < 0.001. (B) Analysis of EV‐LINC00853 ROC curve in patients with HCC vs control (healthy, CH, and LC). Statistically significant differences in the AUC were relative to AUC of 0.5. Target gene expression was calculated relative to that of HMBS.

3.4. Diagnostic performance of EV‐LINC00853 for early‐stage HCC

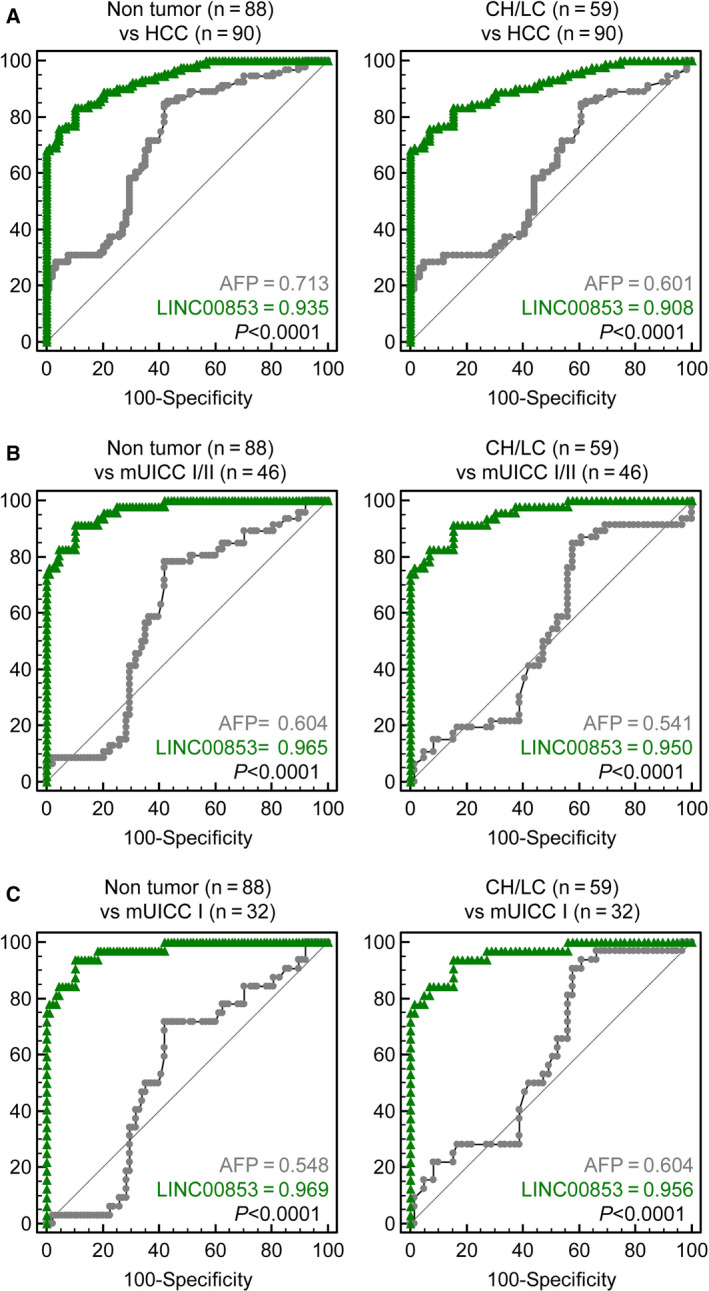

Next, we evaluated the diagnostic value of EV‐LINC00853 for early‐stage HCC and compared it with the diagnostic performance of AFP. Table 2 and Fig. 4A‐C summarize the diagnostic performance and ROC curves of EV‐LINC00853 and AFP for the diagnosis of HCC based on the tumor stage and when compared with different control groups. EV‐LINC00853 displayed excellent discriminatory ability in the diagnosis of all‐stage HCC (Fig. 4A) as well as early‐stage HCC (Fig. 4C). The high diagnostic performance of EV‐LINC00853 was maintained even when the control group was changed from patients without HCC to patients with CH or LC. The ROC AUC of EV‐LINC00853 (0.908–0.969) was significantly higher than that of AFP (0.541–0.713) in all subgroup analyses (P < 0.001 for all comparisons). Using a 14‐fold increase as cutoff for EV‐LINC00853 expression, and 20 ng·mL−1 as cutoff for the AFP level, EV‐LINC00853 had a sensitivity of 93.75%, specificity of 89.77%, and 76.92% positive predictive value, while AFP showed only 9.38% sensitivity, 72.73% specificity, and 11.11% positive predictive value for the diagnosis of early‐stage HCC (mUICC stage I).

Table 2.

Comparative analysis between diagnosis of HCC using serum EV‐LINC00853 and serum AFP. PPV, positive predictive value; NPV, negative predictive value.

| P vs AFP | AUC | 95% CI | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | PPV (%) | NPV (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HCC vs Nontumor | |||||||

| AFP (20 ng·mL−1) | 1 | 0.713 | 0.641–0.778 | 37.78 | 72.72 | 58.62 | 53.33 |

| LINC00853 (14‐fold) | < 0.0001 | 0.935 | 0.888–0.966 | 83.33 | 89.77 | 89.29 | 84.04 |

| HCC vs CH/LC | |||||||

| AFP (20 ng·mL−1) | 1 | 0.601 | 0.517–0.680 | 37.78 | 59.32 | 58.62 | 38.46 |

| LINC00853 (14‐fold) | < 0.0001 | 0.908 | 0.850–0.949 | 83.33 | 84.75 | 89.29 | 76.92 |

| mUICC I/II vs Nontumor | |||||||

| AFP (20 ng·mL−1) | 1 | 0.604 | 0.516–0.687 | 15.22 | 72.78 | 22.58 | 62.14 |

| LINC00853 (14‐fold) | < 0.0001 | 0.965 | 0.918–0.989 | 91.30 | 89.77 | 82.35 | 95.18 |

| mUICC I/II vs CH/LC | |||||||

| AFP (20 ng·mL−1) | 1 | 0.541 | 0.441–0.638 | 15.22 | 59.32 | 22.58 | 47.30 |

| LINC00853 (14‐fold) | < 0.0001 | 0.950 | 0.889–0.983 | 91.30 | 84.75 | 82.35 | 92.59 |

| mUICC I vs Nontumor | |||||||

| AFP (20 ng·mL−1) | 1 | 0.548 | 0.455–0.639 | 9.38 | 72.73 | 11.11 | 68.82 |

| LINC00853 (14‐fold) | 0.1016 | 0.969 | 0.920–0.992 | 93.75 | 89.77 | 76.92 | 97.53 |

| mUICC I vs CH/LC | |||||||

| AFP (20 ng·mL−1) | 1 | 0.604 | 0.496–0.705 | 9.38 | 59.32 | 11.11 | 54.69 |

| LINC00853 (14‐fold) | < 0.0001 | 0.956 | 0.891–0.988 | 93.75 | 84.75 | 76.92 | 96.15 |

Fig. 4.

Diagnostic power of EV‐LINC00853 in all‐stage and early‐stage HCC. (A) AUROCs for discriminating patients with all‐stage HCC from the nontumor subjects (healthy, CH, and LC) (left) and from patients at high risk of developing HCC (CH and LC) (right). (B) AUROCs for discriminating patients with mUICC stage I or II HCC from nontumor subjects (healthy, CH, and LC) (left) and from patients at high risk of developing HCC (CH and LC) (right). (C) AUROCs for discriminating patients with mUICC stage I tumors from the nontumor subjects (healthy, CHs, and LC) (left) and from patients at high risk of developing HCC (CH and LC) (right). Statistically significant differences in AUC were between EV‐LINC00853 and AFP. Target gene expression was calculated relative to that of HMBS.

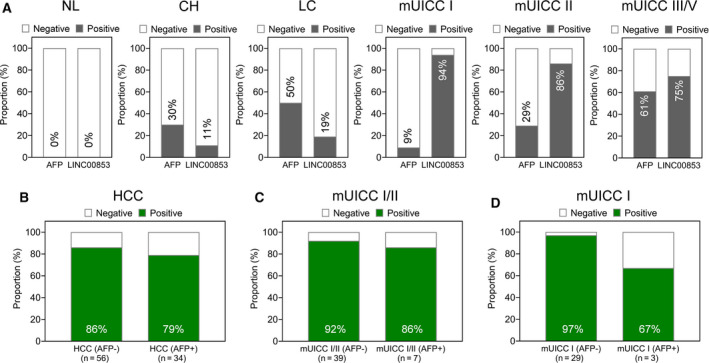

Figure 5A compares the positivity rate of EV‐LINC00853 and AFP in healthy subjects and in the CH, LC, and HCC groups. Interestingly, EV‐LINC00853 had a high positivity rate even in AFP‐negative HCC (Fig. 5B–D). In mUICC stage I tumors, EV‐LINC00853 had 97% positivity in AFP‐negative HCC and 67% positivity in AFP‐positive HCC (Fig. 5D).

Fig. 5.

The positive rate of EV‐LINC00853 in all‐stage and early‐stage HCC. (A) The rate of positive results of AFP and EV‐LINC00853 in patients with each liver disease status. The cutoff for positivity was defined as a 14‐fold increase in EV‐LINC00853 expression, and 20 ng·mL−1 for AFP level. (B) The rate of positive results for EV‐LINC00853 by AFP status in patients with HCC. (C) The rate of positive results for EV‐LINC00853 by AFP status in patients with mUICC I/II. (D) The rate of positive results for EV‐LINC00853 by AFP status in patients with mUICC I. Target gene expression was calculated relative to that of HMBS.

3.5. Prognostic performance of EV‐LINC00853 in the validation cohort

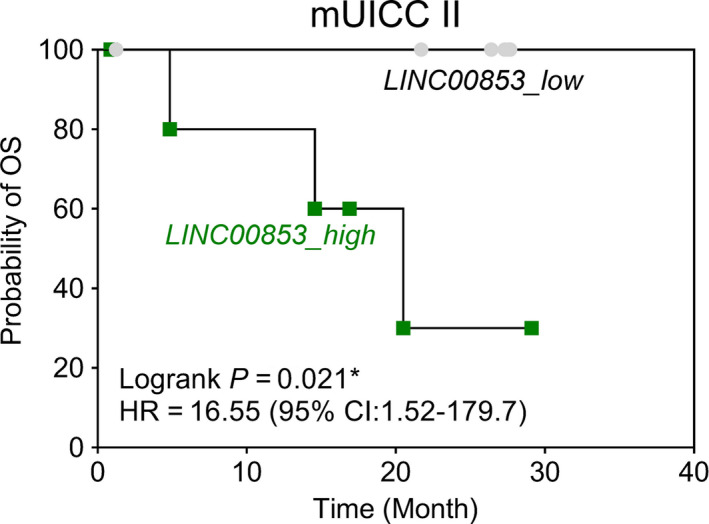

Previous survival analyses showed that high tissue LINC00853 expression was associated with poor overall and disease‐free survival in TCGA_LIHC dataset (Fig. 1F). Therefore, we evaluated the prognostic power of EV‐LINC00853 in our validation cohort. In mUICC stage II HCC, patients with high EV‐LINC00853 expression had lower overall survival rate than those with low EV‐LINC00853 expression (Fig. 6, HR = 16.55, 95% CI = 1.52–179.7, log‐rank P = 0.021). EV‐LINC00853 expression was not associated with the overall survival rate in other‐stage HCC (Fig. S3).

Fig. 6.

Prognostic power of EV‐LINC00853 expression in the validation cohort. The Kaplan–Meier survival curves for overall survival based on EV‐LINC00853 expression in patients with mUICC II HCC (Log‐rank test; *P < 0.05). Target gene expression was calculated relative to that of HMBS.

4. Discussion

In this study, we identified seven lncRNAs that were differentially expressed between the HCC and the nontumor tissues using TCGA_LIHC data. Among them, LINC00853 was a novel lncRNA that has never been reported in association with HCC or other malignancies. Interestingly, LINC00853 was upregulated in serum EVs, but not in the serum of patients with HCC. In the validation cohort consisting of 90 HCC subjects and 92 non‐HCC subjects, EV‐LINC00853 had better discriminative power in the diagnosis of all‐stage HCC and early‐stage HCC (AUC = 0.935 and 0.969, respectively) than AFP (AUC = 0.713 and 0.548, respectively).

LncRNAs exhibit tissue‐specific and species‐specific expression patterns and are also expressed in a regular manner [22], allowing them to serve as diagnostic biomarkers and prognostic factors in various disease states, including HCC [11, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41]. Plasma or serum DANCR, JPX, LINC00974, LINC01225, lncRNA‐P34822, lnc‐RCDH9‐13:1, LRB1, SPRY4‐IT1, UCA1, uc003wbd, WRAP53, and ZFAS1 have been reported to show 51.1–92.7% sensitivity and 50.0–100% specificity for the diagnosis of HCC [26, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 35, 36, 37, 38, 40]. Interestingly, elevated levels of lnc‐PCDH9–13:1 can be detected in the saliva of patients with early‐stage as well as advanced‐stage HCC [40]. Accumulating evidence suggests that EV transfer of functional lncRNA between cells may play an important role in cancer development and tumor chemoresistance by altering and/or regulating local cellular microenvironments [14]. Various EV‐derived lncRNAs, including lncRNA‐HEIH, LINC02394, LINC0635, LINC00161, and JPX, are potential diagnostic biomarkers for HCC [15, 16, 17, 18].

To the best of our knowledge, our study is the first to report LINC00853 as a novel HCC‐related EV‐derived biomarker. We believe EV‐LINC00853 will be useful for diagnosing early‐stage tumors without elevated AFP levels. In the present study, only 9% of the early HCC (mUICC stage I) cases were AFP‐positive, while 94% of them were EV‐LINC00853‐positive. Moreover, 97% of the AFP‐negative early‐stage HCC cases were positive for EV‐LINC00853. These results contrast with those of the previous studies which reported that lncRNA expression is correlated with AFP levels [31, 38]. LINC00853 is likely to act independently of AFP, and thus, it may be a more useful biomarker in patients with CH or LC who sometimes exhibit elevated AFP levels in the absence of HCC, leading to false‐positive results.

LINC00853 is a 1826 nucleotide‐long lncRNA located on the chromosome 1p33. However, little is known about its biological function in disease, including malignancy. Generally, lncRNAs exert their influences via epigenetic modifications, such as chromatin modulation and DNA methylation, altering the stability of proteins and complexes, or by acting as miRNA sponge. Through these mechanisms of action, lncRNAs have been implicated in the six hallmarks of cancer: self‐sustained growth signaling, resistance to growth inhibition, avoidance of apoptosis, uncontrolled proliferation, promotion of angiogenesis, and metastasis [42]. In HCC, the lncRNA HOTAIR induces epigenetic silencing of the HOXD locus [43], HULC may function as a competing endogenous RNA [44], while TERC forms part of the catalytic center of the telomerase complex [45]. Moreover, several lncRNAs have been shown to be involved in Wnt/β‐catenin and STAT3 signaling, cancer stem cells, and epithelial‐to‐mesenchymal transition in HCC [46].

In our study, EV‐LINC00853 expression was associated with overall survival only in patients with mUICC stage II HCC. In fact, the positivity rate of EV‐LINC00853 decreased with increasing tumor stage, suggesting that overexpression of EV‐LINC00853 may not reflect aggressiveness of HCC. Considering that tissue expression of LINC00853 increased with tumor progression in TCGA_LIHC dataset, prognostic performance of EV‐LINC00853 ought to be evaluated in a larger number of patients to confirm these results.

The current study has several limitations. First, we did not investigate the functional role of EV‐LINC00853 in HCC development. Considering that little is known about LINC00853 and its roles in cancer, this is an area that warrants further research. Second, we did not confirm the diagnostic performance of EV‐LINC00853 in an external patient cohort. HCC is a heterogeneous disease with various underlying etiologies, variable global prevalence, and many poorly defined prognostic patient subsets. Ours was a single‐center study whereby hepatitis B was the cause of CH, LC, and HCC in a vast majority of the subjects; thus, the results may not be directly generalizable to patient populations with different etiological backgrounds. For these reasons, large multicenter studies involving patients with a variety of liver diseases and originating from different geographical regions will be needed to comprehensively evaluate the diagnostic and the prognostic usefulness of the lncRNA biomarkers [46]. Third, we did not explore exo‐LINC00853 expression in malignancies other than HCC; thus, we could not confirm its specificity for HCC. However, majority of the lncRNAs are highly tissue‐specific and it is possible that some may be specifically expressed in HCC, allowing for fast diagnosis and better disease management [22, 46]. Finally, due to the limited amount of human serum samples available (300 μL/sample), we were unable to use EV separation methods such as ultracentrifugation [47, 48], as recommended by MISEV2018 [49]. However, through preliminary experiments, we identified the optimal precipitation kit and RNA isolation method to use with a small amount of sample (data not shown), and confirmed that the extracted EVs satisfied the MISEV2018 criteria (Fig. 2).

5. Conclusions

A member of the lncRNA family, LINC00853, was significantly expressed in the EVs of HCC patients. EV‐LINC00853 had excellent and significantly better discriminatory ability in the diagnosis of both all‐stage HCC and early HCC than did AFP. Furthermore, EV‐LINC00853 showed high positivity even in AFP‐negative early HCC cases. Our findings indicate that EV‐derived LINC00853 can serve as a potential noninvasive diagnostic biomarker for HCC that may be of particular value in patients with AFP‐negative tumors.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Author contributions

SWN, JWE, and JYC conceptualized the study. GOB and SS contributed to methodology. HRA and CWS curated the data. SSK and JWE wrote—original draft preparation. HJC wrote—review and editing. SSK, JWE, and JYC funded acquisition. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Supporting information

Table S1. Seven long non‐coding RNAs overexpressed in hepatocellular carcinoma.

Fig. S1. Six known lncRNAs expression in HCC cohorts.

Fig. S2. Age‐related LINC00853 expression in subjects without HCC.

Fig. S3. Prognostic power of EV‐LINC00853 expression in the validation cohort.

Acknowledgements

The biospecimens and data used for this study were provided by the Biobank of Ajou University Hospital, a member of Korea Biobank Network.

This research was supported by the Bio & Medical Technology Development Program of the National Research Foundation (NRF) funded by the Korean government (MSIT) (NRF‐2018M3A9E8023861, NRF‐2019R1C1C1007366, NRF‐2017R1D1A1B03033996, NRF‐2019R1C1C1004580).

Data accessibility

All genomic data were obtained from The Cancer Genome Atlas liver hepatocellular carcinoma project (TCGA_LIHC) and the GEO database of the NCBI (Accession Numbers: GSE94660, GSE114564, GSE124535).

References

- 1. Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Siegel RL, Torre LA & Jemal A (2018) Global cancer statistics 2018: globocan estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin 68, 394–424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Global Burden of Disease Liver Cancer Collaboration , Akinyemiju T, Abera S, Ahmed M, Alam N, Alemayohu MA, Allen C, Al‐Raddadi R, Alvis‐Guzman N, Amoako Y et al (2017) The burden of primary liver cancer and underlying etiologies from 1990 to 2015 at the global, regional, and national level: Results from the global burden of disease study 2015. JAMA Oncol 3, 1683–1691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. European Association for the Study of the Liver (2018) EASL clinical practice guidelines: management of hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol 69, 182–236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Singal A, Volk ML, Waljee A, Salgia R, Higgins P, Rogers MA & Marrero JA (2009) Meta‐analysis: surveillance with ultrasound for early‐stage hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with cirrhosis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 30, 37–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Di Bisceglie AM, Sterling RK, Chung RT, Everhart JE, Dienstag JL, Bonkovsky HL, Wright EC, Everson GT, Lindsay KL, Lok AS et al (2005) Serum alpha‐fetoprotein levels in patients with advanced hepatitis C: results from the HALT‐C trial. J Hepatol 43, 434–441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Geisler S & Coller J (2013) RNA in unexpected places: long non‐coding RNA functions in diverse cellular contexts. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 14, 699–712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ulitsky I & Bartel DP (2013) lincRNAs: genomics, evolution, and mechanisms. Cell 154, 26–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Gutschner T & Diederichs S (2012) The hallmarks of cancer: a long non‐coding RNA point of view. RNA Biol 9, 703–719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Fang Y & Fullwood MJ (2016) Roles, functions, and mechanisms of long non‐coding RNAs in cancer. Genomics Proteomics Bioinformatics 14, 42–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Quagliata L, Matter M, Piscuoglio S, Makowska Z, Heim M & Tornillo L (2013) HOXA13 and HOTTIP expression levels predict patients’ survival and metastasis formation in hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol 58, S39–S40. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Yang Z, Zhou L, Wu LM, Lai MC, Xie HY, Zhang F & Zheng SS (2011) Overexpression of long non‐coding RNA HOTAIR predicts tumor recurrence in hepatocellular carcinoma patients following liver transplantation. Ann Surg Oncol 18, 1243–1250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Brunner AL, Beck AH, Edris B, Sweeney RT, Zhu SX, Li R, Montgomery K, Varma S, Gilks T, Guo X et al (2012) Transcriptional profiling of long non‐coding rnas and novel transcribed regions across a diverse panel of archived human cancers. Genome Biol 13, R75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. De Toro J, Herschlik L, Waldner C & Mongini C (2015) Emerging roles of exosomes in normal and pathological conditions: new insights for diagnosis and therapeutic applications. Front Immunol 6, 203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Sasaki R, Kanda T, Yokosuka O, Kato N, Matsuoka S & Moriyama M (2019) Exosomes and hepatocellular carcinoma: from bench to bedside. Int J Mol Sci 20, 1406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Ma X, Yuan T, Yang C, Wang Z, Zang Y, Wu L & Zhuang L (2017) X‐inactive‐specific transcript of peripheral blood cells is regulated by exosomal JPX and acts as a biomarker for female patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Ther Adv Med Oncol 9, 665–677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Sun L, Su Y, Liu X, Xu M, Chen X, Zhu Y, Guo Z, Bai T, Dong L, Wei C et al (2018) Serum and exosome long non coding RNAs as potential biomarkers for hepatocellular carcinoma. J Cancer 9, 2631–2639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Xu H, Chen Y, Dong X & Wang X (2018) Serum exosomal long noncoding RNAs ENSG00000258332.1 and LINC00635 for the diagnosis and prognosis of hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 27, 710–716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Zhang C, Yang X, Qi Q, Gao Y, Wei Q & Han S (2018) LncRNA‐heih in serum and exosomes as a potential biomarker in the HCV‐related hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Biomark 21, 651–659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Suk KT, Baik SK, Yoon JH, Cheong JY, Paik YH, Lee CH, Kim YS, Lee JW, Kim DJ, Cho SW et al (2012) Revision and update on clinical practice guideline for liver cirrhosis. Korean J Hepatol 18, 1–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Marrero JA, Kulik LM, Sirlin CB, Zhu AX, Finn RS, Abecassis MM, Roberts LR & Heimbach JK (2018) Diagnosis, staging, and management of hepatocellular carcinoma: 2018 practice guidance by the American association for the study of liver diseases. Hepatology 68, 723–750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Cho HJ, Eun JW, Baek GO, Seo CW, Ahn HR, Kim SS, Cho SW & Cheong JY (2020) Serum exosomal microRNA, miR‐10b‐5p, as a potential diagnostic biomarker for early‐stage hepatocellular carcinoma. J Clin Med 9, 281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ward M, McEwan C, Mills JD & Janitz M (2015) Conservation and tissue‐specific transcription patterns of long noncoding RNAs. J Hum Transcr 1, 2–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Birgani MT, Hajjari M, Shahrisa A, Khoshnevisan A, Shoja Z, Motahari P & Farhangi B (2018) Long non‐coding RNA SNHG6 as a potential biomarker for hepatocellular carcinoma. Pathol Oncol Res 24, 329–337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Cao C, Zhang T, Zhang D, Xie L, Zou X, Lei L, Wu D & Liu L (2017) The long non‐coding RNA, SNHG6‐003, functions as a competing endogenous RNA to promote the progression of hepatocellular carcinoma. Oncogene 36, 1112–1122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ding C, Yang Z, Lv Z, Du C, Xiao H, Peng C, Cheng S, Xie H, Zhou L, Wu J et al (2015) Long non‐coding RNA PVT1 is associated with tumor progression and predicts recurrence in hepatocellular carcinoma patients. Oncol Lett 9, 955–963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. El‐Tawdi AH, Matboli M, El‐Nakeep S, Azazy AE & Abdel‐Rahman O (2016) Association of long noncoding RNA and c‐JUN expression in hepatocellular carcinoma. Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 10, 869–877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Ishibashi M, Kogo R, Shibata K, Sawada G, Takahashi Y, Kurashige J, Akiyoshi S, Sasaki S, Iwaya T, Sudo T et al (2013) Clinical significance of the expression of long non‐coding RNA HOTAIR in primary hepatocellular carcinoma. Oncol Rep 29, 946–950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Jing W, Gao S, Zhu M, Luo P, Jing X, Chai H & Tu J (2016) Potential diagnostic value of lncRNA SPRY4‐IT1 in hepatocellular carcinoma. Oncol Rep 36, 1085–1092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Kamel MM, Matboli M, Sallam M, Montasser IF, Saad AS & El‐Tawdi AHF (2016) Investigation of long noncoding RNAs expression profile as potential serum biomarkers in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Transl Res 168, 134–145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Lu J, Xie F, Geng L, Shen W, Sui C & Yang J (2015) Investigation of serum lncRNA‐uc003wbd and lncRNA‐AF085935 expression profile in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma and HBV. Tumour Biol 36, 3231–3236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Luo P, Liang C, Zhang X, Liu X, Wang Y, Wu M, Feng X & Tu J (2018) Identification of long non‐coding RNA ZFAS1 as a novel biomarker for diagnosis of HCC. Biosci Rep 38, BSR20171359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Ma W, Wang H, Jing W, Zhou F, Chang L, Hong Z, Liu H, Liu Z & Yuan Y (2017) Downregulation of long non‐coding RNAs JPX and XIST is associated with the prognosis of hepatocellular carcinoma. Clin Res Hepatol Gastroenterol 41, 163–170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Ma X, Wang X, Yang C, Wang Z, Han B, Wu L & Zhuang L (2016) DANCR acts as a diagnostic biomarker and promotes tumor growth and metastasis in hepatocellular carcinoma. Anticancer Res 36, 6389–6398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Tang J, Jiang R, Deng L, Zhang X, Wang K & Sun B (2015) Circulation long non‐coding RNAs act as biomarkers for predicting tumorigenesis and metastasis in hepatocellular carcinoma. Oncotarget 6, 4505–4515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Tang J, Zhuo H, Zhang X, Jiang R, Ji J, Deng L, Qian X, Zhang F & Sun B (2014) A novel biomarker Linc00974 interacting with KRT19 promotes proliferation and metastasis in hepatocellular carcinoma. Cell Death Dis 5, e1549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Wang C, Ren T, Wang K, Zhang S, Liu S, Chen H & Yang P (2017) Identification of long non‐coding RNA p34822 as a potential plasma biomarker for the diagnosis of hepatocellular carcinoma. Sci China Life Sci 60, 1047–1050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Wang X, Zhang W, Tang J, Huang R, Li J, Xu D, Xie Y, Jiang R, Deng L, Zhang X et al (2016) LINC01225 promotes occurrence and metastasis of hepatocellular carcinoma in an epidermal growth factor receptor‐dependent pathway. Cell Death Dis 7, e2130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Wang ZF, Hu R, Pang JM, Zhang GZ, Yan W & Li ZN (2018) Serum long noncoding RNA LRB1 as a potential biomarker for predicting the diagnosis and prognosis of human hepatocellular carcinoma. Oncol Lett 16, 1593–1601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Xie H, Ma H & Zhou D (2013) Plasma HULC as a promising novel biomarker for the detection of hepatocellular carcinoma. Biomed Res Int 2013, 136106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Xie Z, Zhou F, Yang Y, Li L, Lei Y, Lin X, Li H, Pan X, Chen J, Wang G et al (2018) Lnc‐PCDH9‐13:1 is a hypersensitive and specific biomarker for early hepatocellular carcinoma. EBioMedicine 33, 57–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Xu Y, Wang B, Zhang F, Wang A, Du X, Hu P, Zhu Y & Fang Z (2017) Long non‐coding RNA CCAT2 is associated with poor prognosis in hepatocellular carcinoma and promotes tumor metastasis by regulating Snail2‐mediated epithelial‐mesenchymal transition. Onco Targets Ther 10, 1191–1198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Bartonicek N, Maag JL & Dinger ME (2016) Long noncoding RNAs in cancer: mechanisms of action and technological advancements. Mol Cancer 15, 43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Gupta RA, Shah N, Wang KC, Kim J, Horlings HM, Wong DJ, Tsai MC, Hung T, Argani P, Rinn JL et al (2010) Long non‐coding RNA HOTAIR reprograms chromatin state to promote cancer metastasis. Nature 464, 1071–1076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Wang J, Liu X, Wu H, Ni P, Gu Z, Qiao Y, Chen N, Sun F & Fan Q (2010) Creb up‐regulates long non‐coding RNA, HULC expression through interaction with microRNA‐372 in liver cancer. Nucleic Acids Res 38, 5366–5383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Mitchell M, Gillis A, Futahashi M, Fujiwara H and Skordalakes E (2010) Structural basis for telomerase catalytic subunit TERT binding to RNA template and telomeric DNA. Nat Struct Mol Biol 17, 513–518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Klingenberg M, Matsuda A, Diederichs S & Patel T (2017) Non‐coding RNA in hepatocellular carcinoma: mechanisms, biomarkers and therapeutic targets. J Hepatol 67, 603–618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Helwa I, Cai J, Drewry MD, Zimmerman A, Dinkins MB, Khaled ML, Seremwe M, Dismuke WM, Bieberich E, Stamer WD et al (2017) A comparative study of serum exosome isolation using differential ultracentrifugation and three commercial reagents. PLoS One 12, e0170628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Serrano‐Pertierra E, Oliveira‐Rodriguez M, Rivas M, Oliva P, Villafani J, Navarro A, Blanco‐Lopez MC & Cernuda‐Morollon E (2019) Characterization of plasma‐derived extracellular vesicles isolated by different methods: a comparison study. Bioengineering 6, 8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Thery C, Witwer KW, Aikawa E, Alcaraz MJ, Anderson JD, Andriantsitohaina R, Antoniou A, Arab T, Archer F, Atkin‐Smith GK et al (2018) Minimal information for studies of extracellular vesicles 2018 (MISEV2018): a position statement of the international society for extracellular vesicles and update of the MISEV2014 guidelines. J Extracell Vesicles 7, 1535750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1. Seven long non‐coding RNAs overexpressed in hepatocellular carcinoma.

Fig. S1. Six known lncRNAs expression in HCC cohorts.

Fig. S2. Age‐related LINC00853 expression in subjects without HCC.

Fig. S3. Prognostic power of EV‐LINC00853 expression in the validation cohort.

Data Availability Statement

All genomic data were obtained from The Cancer Genome Atlas liver hepatocellular carcinoma project (TCGA_LIHC) and the GEO database of the NCBI (Accession Numbers: GSE94660, GSE114564, GSE124535).