This survey study uses data from a tertiary care center and online patient community to develop and assess the Nasal Outcome Score for Epistaxis in Hereditary Hemorrhagic Telangiectasia outcome measure of epistaxis in patients with hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia.

Key Points

Question

Can a quality-of-life instrument be developed and validated to determine the outcome of epistaxis on physical problems, functional limitations, and emotional consequences in patients with hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia (HHT)?

Findings

This survey study with 401 patients found that the 29-item Nasal Outcome Score for Epistaxis in HHT patient-reported outcome measure, with total scores ranging continuously from 0 to 4, was internally consistent, highly correlated with epistaxis severity, and responsive to change. It had a high test-retest reliability and a minimal clinically important difference of 0.46 points.

Meaning

The Nasal Outcome Score for Epistaxis in HHT outcome measure provides clinicians with a validated measurement of physical, functional, and emotional consequences of HHT-associated epistaxis and can be used as an outcome measure in future epistaxis clinical trials.

Abstract

Importance

Epistaxis is the greatest cause of morbidity in patients with hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia (HHT); because of this, a validated epistaxis-specific quality-of-life instrument for HHT should be made available.

Objective

To develop and validate an epistaxis-specific quality-of-life patient-reported outcome measure for HHT.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This survey study focused on the development and validation of the Nasal Outcome Score for Epistaxis (NOSE) in HTT (NOSE HHT) outcome measure with data prospectively collected from December 10, 2019, to March 15, 2020. A total of 401 patients were recruited from within the Cure Hemorrhagic Telangiectasia online patient advocacy social media network, the Washington University HHT Center of Excellence, and a randomized clinical trial investigating an intranasal timolol gel for HHT-associated epistaxis.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Face and content validity, factor analysis, internal consistency as measured through Cronbach α, construct validity, responsiveness to change, and minimal clinically important difference.

Results

The NOSE HHT was developed and validated with a possible score ranging discretely from 0 to 4 for each of the 29 items and a total score ranging continuously from 0 to 4 after dividing by the total number of items answered. A total of 401 participants completed the NOSE HHT. Factor analysis identified 3 factors that matched the a priori specified subgroups of particular aspects of life affected by HHT-associated epistaxis: physical problems (mean [SD] magnitude, 1.59 [0.83]), functional limitations (mean [SD] magnitude, 1.28 [0.84]), and emotional consequences (mean [SD] magnitude, 1.95 [1.02]). The instrument had high internal consistency with an overall Cronbach α of 0.960. Convergent validity determined the total NOSE HHT score to be a strong predictor of disease severity; total NOSE HHT score can be split up into the following epistaxis severity categories: mild (0-1), moderate (1.01-2), and severe (>2). The instrument was found to be sensitive to change, and the minimal clinically important difference for the total NOSE HHT score was 0.46.

Conclusions and Relevance

Evaluation of the consistency, reliability, and responsiveness of the NOSE HHT survey found it to be a valid instrument to assess severity and change in epistaxis. Study results suggest that the NOSE HHT survey is clinically applicable and useful as an outcome measure of future HHT-associated epistaxis trials.

Introduction

Hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia (HHT) is an inherited autosomal dominant disorder that leads to abnormal formation of blood vessels throughout the body.1 Patient symptoms primarily consist of bleeding from mucosal surfaces to more severe or life-threatening hemorrhage in the lung, brain, or liver. The physical signs of HHT consist of telangiectasias (dilated capillaries) on mucosal and cutaneous skin surfaces and arteriovenous malformations in various internal organs. The telangiectasias tend to spontaneously rupture, most commonly resulting in nasal or gastrointestinal bleeding. By the age 20 years, more than 75% of patients with HHT have developed recurrent epistaxis, which is the leading cause of morbidity in HHT.2,3 Prior studies looking at the effect of HHT-associated epistaxis have found that it is associated with decreased physical functioning, energy, and social functioning.3,4

Currently, there are 2 patient-reported outcome measures for HHT-associated epistaxis. Hoag et al created the Epistaxis Severity Score (ESS), which assesses the frequency, duration, and severity of epistaxis as well as anemia, blood transfusions, and the need for medical attention, all within the last 3 months.5 Although the ESS may serve as a good outcome measure regarding the physical components of epistaxis and its medical therapeutic sequelae, it does not encompass functional or emotional aspects of the quality of life of a patient with HHT. The other HHT-specific instrument is the Epistaxis Questionnaire Quality of Life (EQQoL), which is a 13-item questionnaire designed to measure the patient’s quality of life.6 The EQQoL assesses some psychosocial aspects of HHT-related epistaxis but contains ambiguous questions (eg, “Have your nosebleeds restricted your mental activities?” and “Have you ever spent a bad night because of your nosebleeds?”) rather than specific symptoms and experiences that the patient can rate. No minimal clinically important difference (MCID) was determined for the EQQoL. Since its publication in 2011, the EQQoL has not been used as an outcome measure in any HHT-related trial, perhaps owing to these issues.

Other than regular use of nasal moisturizing agents, no standard-of-care therapy exists for HHT-associated epistaxis.7 With the current and upcoming wave of HHT-associated epistaxis trials, as evidenced by ongoing trials with timolol, doxycycline, and pomalidomide, there is a need for a clinically relevant, validated, and reliable outcome measure that is sensitive to change. Our objective was to develop and validate the Nasal Outcome Score for Epistaxis in Hereditary Hemorrhagic Telangiectasia (NOSE HHT) survey and to assess the instrument’s test-retest reliability and responsiveness to change.

Methods

Creation of the Instrument: Item Selection

The items of the NOSE HHT were obtained from discussion with patients with HHT, physicians who treat HHT, and a review of the available literature, until thematic saturation was reached.3,4 The quality-of-life items were divided into 3 sections: physical problems, functional limitations, and emotional consequences. A pilot instrument was created with 29 items: 6 physical problems, 14 functional limitations, and 9 emotional consequences.

Instrument Scoring

Each item is rated on a 5-point Likert scale with a reference time frame to the last 2 weeks of epistaxis. The prompt for items representing physical problems states, “Please rate how severe the following problems are due to your nosebleeds by circling the number that corresponds to how ‘bad’ each problem is.” Possible answers (and scores) are No problem (0), Mild problem (1), Moderate problem (2), Severe problem (3), or Problem as bad as it can be (4). The prompt for items representing functional limitations states, “Please rate how difficult it is to perform the following tasks due to your nosebleeds.” Possible answers (and scores) are No difficulty (0), Mild difficulty (1), Moderate difficulty (2), Severe difficulty (3), or Complete difficulty (4). The prompt for items representing emotional consequences states, “Please rate how frequently bothered you are by the following due to your nosebleeds.” Possible answers (and scores) are Not bothered (0), Very rarely bothered (1), Rarely bothered (2), Frequently bothered (3), or Very frequently bothered (4). The 29-item pilot instrument’s total score is calculated by dividing the sum of each response by the total number of items answered to get a continuous range of total scores from 0 to 4. For instance, if a patient completes every item, the total sum is divided by 29, but if 1 item is left blank, the total sum would be divided by 28 to get the total score. Each subscore is scored as the sum of the items within that section divided by the total number of items within that section, maintaining the maximum possible score of 4 for each section.

Population Under Study

Participants were enrolled in the study between December 10, 2019, and March 15, 2020. The instrument was distributed through 3 different mediums: (1) Cure Hemorrhagic Telangiectasia, an international HHT patient advocacy group founded in 1991, sent the online Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap) survey link to their HHT patient email list and posted it on their HHT patient Facebook group page (https://curehht.org); (2) patients were recruited while visiting the otolaryngology clinic for HHT-associated epistaxis care; and (3) participants were drawn from a randomized clinical trial using a timolol nasal gel for HHT-associated epistaxis.8 A separate cohort of patients without HHT or epistaxis seen in the otolaryngology clinic for other concerns (eg, auditory impairment) were also recruited to complete the survey. The research protocol was approved under the Washington University in St Louis Institutional Review Board, and all online respondents remained anonymous per the review board. Informed consent was waived by the institutional review board for online participants because the information was provided without personal identifiers. Written informed consent was obtained from patients in the otolaryngology clinic and clinical trial participants.

Patient Surveys

At baseline, participants were asked to complete 4 surveys: the modified Clinical Global Impression–Severity (CGI-S) 5-point Likert scale, Short Form-36 (SF-36), ESS, and NOSE HHT.

A baseline global severity rating of epistaxis was adapted from the CGI-S scale.9 It measures the current severity of each patient’s epistaxis through the prompt, “Please rate how severe your nosebleeds have been in the last 2 weeks.” Response options are No problem, Mild problem, Moderate problem, Severe problem, or Problem as bad as it could be. Because epistaxis varies in frequency, duration, and intensity (eg, dripping vs gushing) in an individual patient, the term severity was used whereby participants chose how severe they perceived their epistaxis to be encompassed by their individual combination of frequency, duration, and intensity.

The SF-36 is a widely used general health questionnaire that assesses 8 subscales: (1) physical functioning, (2) role limitations due to physical health, (3) role limitations due to emotional problems, (4) energy/fatigue, (5) emotional well-being, (6) social functioning, (7) pain, and (8) general health.10 It has been used and validated in a wide variety of conditions, including postoperative recovery after colorectal surgery, stroke, and even HHT.3,4,11 The scores for each subscale range from 0 (least healthy) to 100 (most healthy).

The ESS is the most widely used patient-reported outcome measure specific for HHT-associated epistaxis. The overall score ranges from 0 to 10, with severity of epistaxis categorized as None with an overall score of 0 to 1, Mild as 1 to 4, Moderate as 4 to 7, and Severe as 7 to 10.5

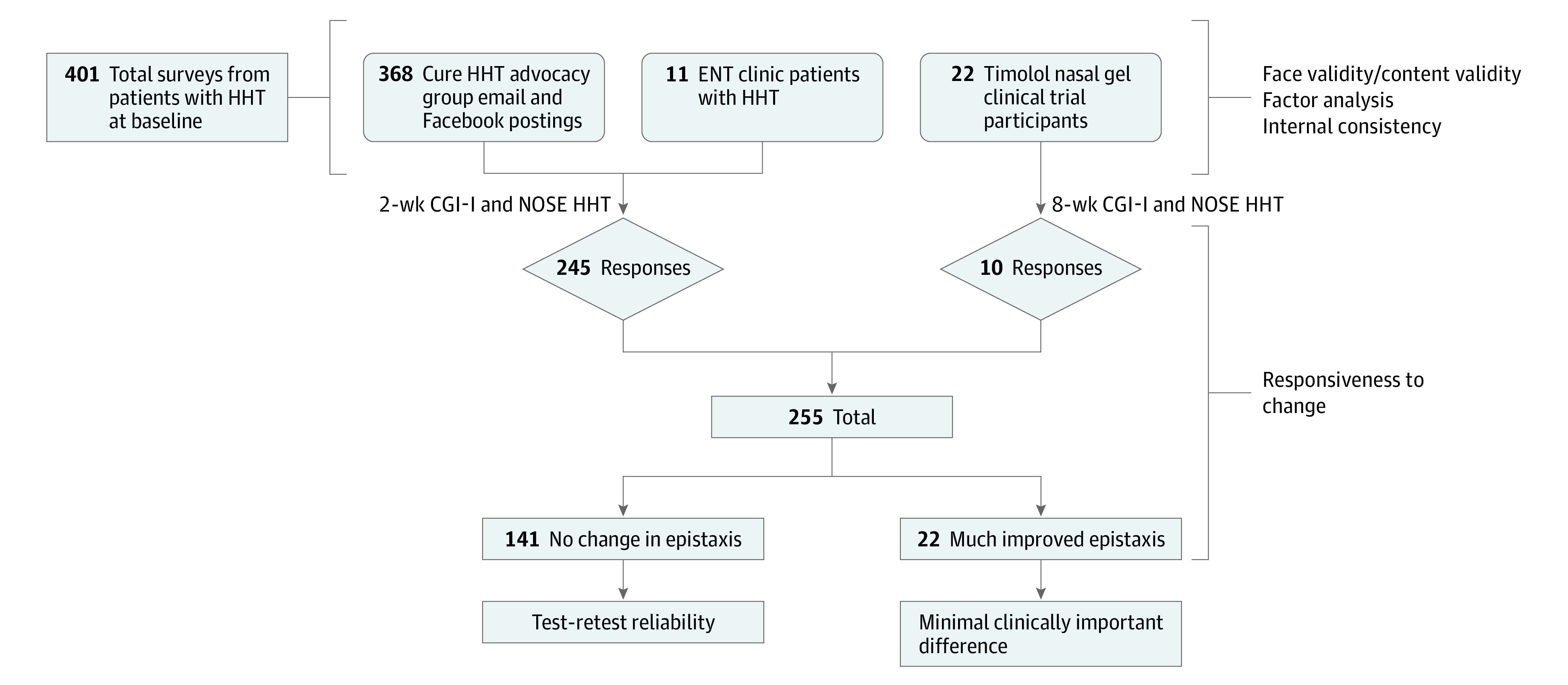

All participants were sent a follow-up set of surveys at week 2 (or week 8, if enrolled in the timolol trial) that included an adapted version of the Clinical Global Impression–Improvement (CGI-I) 5-point Likert scale and the NOSE HHT. The CGI-I measures the patient’s change in epistaxis through the prompt, “Overall, how would you rate the change in your nosebleeds in the last 2 weeks?” Response options are Much worse, Slightly worse, No change, Slightly improved, and Much improved. Figure 1 shows a flowchart of the distribution of surveys and at what point in the study the psychometric and clinimetric properties of the instrument were evaluated. Before performing any analysis, mean imputation was completed for the missing data.

Figure 1. Flowchart and Assessment of the Psychometric and Clinimetric Properties of the NOSE HHT.

CGI-I indicates Clinical Global Impression–Improvement; ENT, ear, nose, and throat; HHT, hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia; NOSE, Nasal Outcome Score for Epistaxis.

Psychometric Validity

The goal of item reduction is to finalize the item selection, allowing for psychometric evaluation of the NOSE HHT survey. Item reduction contains 3 components: (1) face and content validity, (2) factor analysis, and (3) internal consistency. Items are to be considered for elimination by assessing clinical relevance, limiting redundancy, and maximizing internal consistency through Cronbach α.

Items in consideration to be removed from the instrument were initially selected based on face validity (ie, clinical sensibility). Similarly, content validity assesses the relationship of the items on the survey to their overall goal, usually by expert judgment. To evaluate face validity and content validity, a team of 5 otolaryngologists on the 2019 Christopher McMahon Memorial International HHT Guidelines Conference expert panel reviewed the instrument.

Factor analysis is an analytical technique that allows exploration of the relationship between individual survey items. Principal factor analysis was performed to test the loading of each item of the instrument. A promax oblique rotation was applied and the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin statistic was checked to verify sample size adequacy. Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin values greater than 0.8 are typically considered acceptable.12 Factors were kept after analyzing the scree plot and only if it had an eigenvalue of 1 or greater.13

Internal consistency measures how items within an instrument relate to each other and was assessed on all baseline responses. The ordinal scale statistical mechanism to evaluate internal consistency is Cronbach α.14

Construct Validity

The term construct validity, divided into convergent and discriminant validity, refers to the suitability of an instrument for its purpose. To determine convergent validity, we compared the NOSE HHT scores with the ESS, SF-36, and CGI-S scores at baseline. Pearson correlation was used for comparison of the ESS and SF-36 domains, and a 1-way analysis of variance using η2 as the effect size was used for comparison of the CGI-S. Discriminant validity was measured by comparison of NOSE HHT scores between patients with HHT and the cohort of patients without HHT or epistaxis.

Test-Retest Reliability

The test-retest reliability refers to the performance of the instrument when repeated after a period of time by the same user with the same severity of symptoms. The test-retest reliability was assessed by sending all patients who were recruited online and from the ear, nose, and throat clinic 2-week follow-up surveys including the CGI-I and NOSE HHT. Total scores and subscores on the NOSE HHT of patients who reported No Change on the CGI-I at week 2 were compared with their baseline scores using the intraclass correlation coefficient in a 2-way mixed model with absolute agreement. Only 1 participant who had completed the timolol trial had reported No change on the CGI-I, so week 8 scores were not used to measure test-retest reliability.

Responsiveness to Change and MCID

Responsiveness to change refers to the ability of the instrument to capture the change in a patient’s condition. To measure responsiveness, average NOSE HHT scores were determined within each CGI-I response category.

The MCID is the minimum change in total score of the instrument required for patients and physicians to consider a change in epistaxis as a meaningful improvement. MCID was calculated using the within-patient global ratings approach, a type of anchor-based approach, thought to be a clinically relevant and practical approach to calculating the MCID.15,16 The a priori specified anchor was the “Much improved” group among CGI-I respondents. The MCID calculated via the anchor-based approach was compared with the distribution-based method, which measures an outcome based on some level of variability within the data.15,16

Results

Four hundred one participants completed the baseline NOSE HHT survey. Table 1 shows the mean magnitude for each item and subscore of the instrument. The Emotional Consequences subscore had the highest total subscore (mean [SD], 1.95 [1.02]), and the item with the overall largest mean magnitude response was “fear of nosebleeds in public” (mean [SD], 2.63 [1.24]). Among the 401 participants who completed the ESS at baseline, the median frequency of nosebleeds was “several per week,” the median duration was 6 to 15 minutes, and 252 participants (63%) considered their nosebleeds not gushing or pouring.

Table 1. Mean Magnitude for Baseline 29-Item NOSE HHT (N = 401).

| Variable | Mean (SD) magnitude | % Endorsed (ie, score >0) |

|---|---|---|

| Physical problems | 1.59 (0.83) | NA |

| Blood running down back of your throat | 1.94 (1.07) | 91 |

| Blocked up/stuffy nose | 1.84 (1.04) | 88.5 |

| Nasal crusting | 1.74 (1.03) | 86.5 |

| Fatigue | 1.69 (1.23) | 78.3 |

| Shortness of breath | 1.24 (1.19) | 63.1 |

| Decreased sense of smell/taste | 1.07 (1.13) | 57.6 |

| Functional limitations | 1.28 (0.84) | NA |

| Blow your nose | 2.19 (1.30) | 86.8 |

| Bend over/pick something up off the ground | 1.76 (1.21) | 82.8 |

| Breathe through your nose | 1.57 (1.15) | 78.3 |

| Exercise | 1.50 (1.19) | 76.6 |

| Work at your job (or school) | 1.29 (1.19) | 68.3 |

| Stay asleep | 1.28 (1.11) | 69.3 |

| Enjoy time with family/friends | 1.20 (1.04) | 69.6 |

| Eat certain foods (eg, spicy) | 1.18 (1.28) | 56.9 |

| Have intimacy with spouse or significant other | 1.17 (1.17) | 63.3 |

| Travel (eg, by plane) | 1.11 (1.20) | 59.4 |

| Fall asleep | 1.00 (1.06) | 57.6 |

| Clean your house/apartment | 0.98 (1.04) | 57.4 |

| Go outdoors regardless of the weather/season | 0.96 (1.06) | 55.1 |

| Cook/prepare meal | 0.71 (0.93) | 45.1 |

| Emotional consequences | 1.95 (1.02) | NA |

| Fear of nosebleeds in public | 2.63 (1.24) | 92.8 |

| Fear of not knowing when your next nosebleed will be | 2.47 (1.26) | 90.0 |

| Getting blood on your clothes | 2.40 (1.27) | 89.5 |

| Fear of not being able to stop a nosebleed | 2.11 (1.37) | 79.6 |

| Embarrassment | 2.02 (1.30) | 82.8 |

| Frustration/restlessness/irritability | 1.77 (1.33) | 75.3 |

| Reduced concentration | 1.57 (1.33) | 69.3 |

| Sadness | 1.55 (1.34) | 67.6 |

| The need to buy new clothes | 1.07 (1.22) | 53.9 |

Abbreviations: HHT, hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia; NA, not applicable; NOSE, Nasal Outcome Score for Epistaxis.

The average estimated time to complete the survey was approximately 5 minutes. No participant reported inability to complete the survey. The number of baseline NOSE HHT responses with any missing value was 15 (4%), and the total number of missing values for each survey item ranged from 0 to 5.

After analyzing for face and content validity, performing factor analysis, and assessing internal consistency, all items were determined to contribute, and thus the final instrument remained at 29 total items.

The 5 otolaryngologists (including J.F.P.) on the 2019 Christopher McMahon Memorial International HHT Guidelines expert panel determined that all items were clinically sensible and relevant to HHT-associated epistaxis.

The scree plot and eigenvalues suggested that the instrument loads with 3 total factors were nearly perfectly aligned by the a priori grouping of the items. All 29 items loaded onto 1 of the 3 factors. The unrotated 3-factor solution explains 92% of the cumulative variance. See eTable 1 in the Supplement for factor loadings and uniqueness values after oblique promax rotation. The Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin value was 0.95, verifying the sample adequacy for this analysis.

The overall Cronbach α for the baseline assessment was 0.960, suggesting good internal consistency within the NOSE HHT. The Cronbach α after removal of any individual item would be between 0.957 and 0.960.

Construct Validity

Convergent Validity

The association of the total and subscore results on the NOSE HHT with the CGI-S and ESS at baseline are shown in Table 2. The 1-way analysis of variance resulted in an η2 effect size between the CGI-S and total NOSE HHT score of 0.39, which is considered large.17 Based on this strong effect size in distinguishing among the severity of epistaxis at baseline, the tool can be used at a single time point to determine severity of epistaxis. We combined the 5 baseline CGI-S groups into 3 total groups, determining epistaxis severity with the following total NOSE HHT scores: mild (0-1), moderate (1.01-2), and severe (>2).

Table 2. Association of NOSE HHT Score and Clinical Global Impression–Severity.

| CGI-Sa | No. of patients | Mean (SD) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ESS | Physical problems subscore | Functional limitations subscore | Emotional consequences subscore | Total NOSE HHT score | ||

| No problem | 32 | 2.71 (1.92) | 0.91 (0.69) | 0.52 (0.62) | 1.05 (0.95) | 0.76 (0.67) |

| Mild problem | 128 | 3.91 (1.50) | 1.14 (0.68) | 0.80 (0.62) | 1.39 (0.87) | 1.05 (0.62) |

| Moderate problem | 152 | 5.40 (1.52) | 1.75 (0.75) | 1.43 (0.70) | 2.19 (0.87) | 1.73 (0.66) |

| Severe problem | 74 | 6.64 (1.56) | 2.11 (0.67) | 1.92 (0.70) | 2.63 (0.77) | 2.18 (0.60) |

| Problem as bad as it could be | 14 | 7.79 (1.87) | 2.63 (0.60) | 2.45 (0.79) | 3.07 (0.77) | 2.68 (0.67) |

| Total | 401b | 5.03 (2.02) | 1.59 (0.83) | 1.28 (0.84) | 1.95 (1.02) | 1.55 (0.81) |

Abbreviations: CGI-S, Clinical Global Impression–Severity; ESS, Epistaxis Severity Score; HHT, hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia; NOSE, Nasal Outcome Score for Epistaxis.

CGI-S and total NOSE HHT η2 = 0.39.

One participant had a missing CGI-S value.

Pearson correlation of the ESS with the physical problems, functional limitations, and emotional consequences subscores and total NOSE HHT score were 0.61 (95% CI, 0.54-0.66), 0.68 (95% CI, 0.62-0.73), 0.62 (95% CI, 0.55-0.68), and 0.70 (95% CI, 0.65-0.75), respectively. Total mean (SD) for the physical problems, functional limitations, and emotional consequences subsections and the total NOSE HHT score were 1.59 (0.83), 1.28 (0.84), 1.95 (1.02), and 1.55 (0.81), respectively (Table 2).

Pearson correlation of the total and subscore results on the NOSE HHT with each of the SF-36 health concepts is shown in eTable 2 in the Supplement. All Total NOSE HHT score correlations were between –0.49 to –0.69, showing a moderate to strong negative relationship in each SF-36 subscale and consistent with the scoring of the 2 different instruments: higher SF-36 scores and lower NOSE HHT scores imply healthier patients and less disease burden.

Discriminant Validity

A total of 24 patients seen in the otolaryngology clinic without HHT or epistaxis were recruited. The mean (SD) total NOSE HHT score for these patients was 0.04 (0.08), compared with the mean (SD) score of 1.55 (0.81) for patients with HHT.

Test-Retest Reliability

Intraclass correlation coefficient analysis was performed between the NOSE HHT subscores and total score at baseline and week 2 among the 141 participants reporting No change on the CGI-I. The intraclass correlation coefficient for the physical problems, functional limitations, and emotional consequences subscores, and total NOSE HHT score were 0.89 (95% CI, 0.84-0.92), 0.91 (95% CI, 0.87-0.93), 0.91 (95% CI, 0.88-0.94), and 0.93 (95% CI, 0.90-0.96), respectively, indicating a high test-retest reliability.

Responsiveness and MCID

A total of 255 participants completed the follow-up survey 2 weeks after completing the baseline survey and self-reported perceived change in epistaxis through the CGI-I. Figure 2 shows that the NOSE HHT was responsive and sensitive to change among patients reporting Much improved (22 [5%]; mean [SD] change in total NOSE HHT, 0.55 [0.62]), No change (141 [35%]; mean [SD] change in total NOSE HHT, 0.09 [0.30]), and Much worse (5 [1%]; mean [SD] change in total NOSE HHT, –0.42 [0.81]). Using the within-patient global ratings anchor-based method, the MCID is the difference between the mean changes of the Much improved and No change groups, giving an MCID of 0.46. The Much improved group was used rather than the Slightly improved group, as we wanted to ensure a true improvement owing to the fluctuating nature of HHT-associated epistaxis. Using the distribution-based method, an MCID of 0.46 is equivalent to 0.56 SDs of the baseline NOSE HHT scores (mean [SD], 1.55 [0.81]), which is consistent with a moderate-to-large change.18

Figure 2. Determination of the MCID .

The MCID is calculated as the difference from baseline to follow-up between the mean total NOSE HHT score of patients who reported Much improved (mean, 0.55) and those who reported No change (mean, 0.09) on the CGI-I scale. The horizontal dashed lines represent the mean differences for their respective groups. The ends of the boxes represent the first and third quartiles (ie, 25th and 75th percentiles), and the whiskers extend 1.5 box lengths above and below each box. Circles represent outliers. HHT indicates hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia; MCID, minimal clinically important difference; NOSE, Nasal Outcome Score for Epistaxis.

Discussion

We developed and validated the NOSE HHT with a total of 401 patients with HHT, assessing for consistency, validity, and responsiveness of the instrument. As noted, the emotional consequences subsection had the highest average score of the 3 domains, consistent with our clinical experience, as the toll that daily epistaxis can take on patients with HHT is readily apparent.

Benefits of the NOSE HHT Over Existing Instruments

The NOSE HHT survey items refer to a time frame of epistaxis within the past 2 weeks, as clinical experience has shown a high variability in week-by-week epistaxis and difficulty recalling epistaxis patterns in the 3-month time frame of the ESS. The ESS involves questions regarding health care use (eg, seeking medical attention for nose bleeding and receiving a red blood cell transfusion), which is highly variable among patients and dependent on factors such as socioeconomic status and proximity to a health care facility. Furthermore, the method in which the MCID was calculated for the ESS does not involve any actual time period when a change in epistaxis can occur. The authors calculated the MCID using a distribution-based approach and an anchor-based approach followed by an averaging of the 2 values.19

Validity of Different HHT-Associated Epistaxis Instruments

The validity, responsiveness, and MCID of the NOSE HHT was compared with the ESS and EQQol in Table 3. Of the 3 instruments, only the NOSE HHT was assessed adequately on discriminant validity and MCID.

Table 3. Comparison Among Patient-Reported Outcome Measures for HHT-Associated Epistaxis.

| Epistaxis PROM | Content validity | Internal consistency | Validity | Test-retest reliability | Responsiveness | MCID | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Concurrent | Discriminant | ||||||

| NOSE HHT | +a | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| ESS | + | 0 | + | 0 | 0 | 0 | − |

| EQQol | + | + | + | 0 | + | + | 0 |

Abbreviations: ESS, Epistaxis Severity Score; EQQol, Epistaxis Questionnaire Quality of Life; HHT, hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia; MCID, minimal clinically important difference; NOSE, Nasal Outcome Score for Epistaxis; PROM, patient-reported outcome measure.

+ indicates completed adequately; − indicates completed but inadequate; 0 indicates not completed.

The use of the Cure Hemorrhagic Telangiectasia online social media portal as a means of recruitment ensured broad representation of patients with HHT and generalizability of the results to all patients with HHT. In addition, the use of the online community ensured an adequate sample size. The continued expansion of social media and new online patient advocacy groups represent opportunities to enhance the efficiency of recruitment in clinical research, especially for rare diseases.

Strengths and Limitations

One limitation of the study is that because the majority of the data were collected via Cure Hemorrhagic Telangiectasia’s online patient advocacy group, patients with HHT patients who lacked access to the internet were largely excluded. It is possible that patients without HHT filled out the survey, and the specific demographics of these participants were not collected. Given the compassion, goodwill, and altruism of the patients and their families affected by this rare and debilitating condition who participate in the online HHT community, we think the benefits of recruiting participants from this online rare disease community far outweigh the limitations.

Conclusions

From the consistency, reliability, and responsiveness of the NOSE HHT survey in our cohort, we propose that the NOSE HHT be used as an outcome measure in future HHT-associated epistaxis treatment trials. The 2-week reference interval of the NOSE HHT permits monitoring of epistaxis every 2 weeks to allow determination of the time frame in which a particular intervention takes its effect, an approach routinely used in large chronic rhinosinusitis trials repeatedly assessing change on the widely used 20-Item Sino-Nasal Outcome Test (SNOT-22).20,21

Our results suggest that the NOSE HHT survey fulfills the need for a clinically relevant, validated, reliable, and responsive outcome measure for use by physicians within clinical trials and when treating patients with HHT.

eTable 1. Principal Components Factor Analysis Loading of NOSE HHT Items

eTable 2. Pearson Correlation of SF-36 and NOSE HHT Scores

References

- 1.McDonald J, Bayrak-Toydemir P, Pyeritz RE. Hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia: an overview of diagnosis, management, and pathogenesis. Genet Med. 2011;13(7):607-616. doi: 10.1097/GIM.0b013e3182136d32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dheyauldeen S, Abdelnoor M, Bachmann-Harildstad G. The natural history of epistaxis in patients with hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia in the Norwegian population: a cross-sectional study. Am J Rhinol Allergy. 2011;25(4):214-218. doi: 10.2500/ajra.2011.25.3616 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Geisthoff UW, Heckmann K, D’Amelio R, et al. Health-related quality of life in hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2007;136(5):726-733. doi: 10.1016/j.otohns.2006.12.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pasculli G, Resta F, Guastamacchia E, Di Gennaro L, Suppressa P, Sabbà C. Health-related quality of life in a rare disease: hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia (HHT) or Rendu-Osler-Weber disease. Qual Life Res. 2004;13(10):1715-1723. doi: 10.1007/s11136-004-7865-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hoag JB, Terry P, Mitchell S, Reh D, Merlo CA. An epistaxis severity score for hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia. Laryngoscope. 2010;120(4):838-843. doi: 10.1002/lary.20818 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ingrand I, Ingrand P, Gilbert-Dussardier B, et al. Altered quality of life in Rendu-Osler-Weber disease related to recurrent epistaxis. Rhinology. 2011;49(2):155-162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Whitehead KJ, Sautter NB, McWilliams JP, et al. Effect of topical intranasal therapy on epistaxis frequency in patients with hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2016;316(9):943-951. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.11724 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Timolol gel for epistaxis in hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia (ETIC-HHT). Clinicaltrials.gov identifier: NCT04139018. Updated December 6, 2019. Accessed April 2, 2020. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04139018

- 9.Busner J, Targum SD. The clinical global impressions scale: applying a research tool in clinical practice. Psychiatry (Edgmont). 2007;4(7):28-37. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ware JE Jr, Sherbourne CD. The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36), I: conceptual framework and item selection. Med Care. 1992;30(6):473-483. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199206000-00002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lennox PA, Hitchings AE, Lund VJ, Howard DJ. The SF-36 health status questionnaire in assessing patients with epistaxis secondary to hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia. Am J Rhinol. 2005;19(1):71-74. doi: 10.1177/194589240501900112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Spicer J. Making Sense of Multivariate Data Analysis: An Intuitive Approach. 1st ed. Sage; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kaiser HF. The application of electronic computers to factor analysis. Educ Psychol Meas. 1960;20(1):141-151. doi: 10.1177/001316446002000116 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cronbach LJ. Coefficient alpha and the internal structure of tests. Psychometrika. 1951;16(3):297-334. doi: 10.1007/BF02310555 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kallogjeri D, Spitznagel EL Jr, Piccirillo JF. Importance of defining and interpreting a clinically meaningful difference in clinical research. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. Published online December 5, 2019. doi: 10.1001/jamaoto.2019.3744 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wright A, Hannon J, Hegedus EJ, Kavchak AE. Clinimetrics corner: a closer look at the minimal clinically important difference (MCID). J Man Manip Ther. 2012;20(3):160-166. doi: 10.1179/2042618612Y.0000000001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Miles J, Shevlin M. Applying Regression and Correlation: A Guide for Students and Researchers. 1st ed. Sage; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cohen J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences. L Erlbaum Associates; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yin LX, Reh DD, Hoag JB, et al. The minimal important difference of the epistaxis severity score in hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia. Laryngoscope. 2016;126(5):1029-1032. doi: 10.1002/lary.25669 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Piccirillo JF, Merritt MG Jr, Richards ML. Psychometric and clinimetric validity of the 20-Item Sino-Nasal Outcome Test (SNOT-20). Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2002;126(1):41-47. doi: 10.1067/mhn.2002.121022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bachert C, Mannent L, Naclerio RM, et al. Effect of subcutaneous dupilumab on nasal polyp burden in patients with chronic sinusitis and nasal polyposis: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2016;315(5):469-479. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.19330 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eTable 1. Principal Components Factor Analysis Loading of NOSE HHT Items

eTable 2. Pearson Correlation of SF-36 and NOSE HHT Scores